Binding of Isaac

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 26 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 26 min

The Binding of Isaac (Hebrew: עֲקֵידַת יִצְחַק, romanized: ʿAqēḏaṯ Yīṣḥaq), or simply "The Binding" (הָעֲקֵידָה, hāʿAqēḏā), is a story from chapter 22 of the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible. In the biblical narrative, God orders Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac on the mountain called Jehovah-jireh in the region of Moriah. As Abraham begins to comply, having bound Isaac to an altar, he is stopped by the Angel of the Lord; a ram appears and is slaughtered in Isaac's stead, as God commends Abraham's pious obedience to offer his son as a human sacrifice.

Especially in art, the episode is often called the Sacrifice of Isaac, although in the end Isaac was not sacrificed. Various scholars suggest that the original story of Abraham and Isaac may have been of a completed human sacrifice, later altered by redactors to substitute a ram for Isaac, while some traditions, including certain Jewish and Christian interpretations, maintain that Isaac actually was sacrificed. In addition to being addressed by modern scholarship, this biblical episode has been the focus of a great deal of commentary in traditional sources of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Biblical narrative

[edit]

According to the Hebrew Bible, God commands Abraham to offer his son Isaac as a sacrifice.[1] After Isaac is bound to an altar, a messenger from God stops Abraham before he can complete the sacrifice, saying, "now I know you fear God". Abraham looks up and sees a ram and sacrifices it instead of Isaac.

The passage states that the event occurred at "the mount of the LORD"[2] in "the land of Moriah".[3] Abraham then named the place 'Jehovah-jireh' (the Lord will provide).[4] 2 Chronicles 3:1[5] refers to "mount Moriah" as the site of Solomon's Temple, while Psalms 24:3,[6] Isaiah 2:3[7] and 30:29,[8] and Zechariah 8:3[9] use the term "the mount of the LORD" to refer to the site of Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem, the location believed to be the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. In the Samaritan Pentateuch, Genesis 22:14, the phrase YHWH yireh is taken to mean "in the mountain the Lord was seen", the mountain being Mount Gerizim.[10]

Jewish views

[edit]In The Binding of Isaac, Religious Murders & Kabbalah, Lippman Bodoff argues that Abraham never intended to actually sacrifice his son, and that he had faith that God had no intention that he do so.[11] Rabbi Ari Kahn elaborates this view on the Orthodox Union website as follows:

Isaac's death was never a possibility – not as far as Abraham was concerned, and not as far as God was concerned. God's commandment to Abraham was very specific, and Abraham understood it very precisely: Isaac was to be "raised up as an offering," and God would use the opportunity to teach humankind, once and for all, that human sacrifice, child sacrifice, is not acceptable. This is precisely how the sages of the Talmud (Taanit 4a) understood the Akedah. Citing the Prophet Jeremiah's exhortation against child sacrifice (Chapter 19), they state unequivocally that such behavior "never crossed God's mind," referring specifically to the sacrificial slaughter of Isaac. Though readers of this parashah throughout the generations have been disturbed, even horrified, by the Akedah, there was no miscommunication between God and Abraham. The thought of actually killing Isaac never crossed their minds.[12]

In The Guide for the Perplexed, Maimonides argues that the story of the binding of Isaac contains two "great notions". First, Abraham's willingness to sacrifice Isaac demonstrates the limit of humanity's capability to both love and fear God. Second, because Abraham acted on a prophetic vision of what God had asked him to do, the story exemplifies how prophetic revelation has the same truth value as philosophical argument and thus carries equal certainty, notwithstanding the fact that it comes in a dream or vision.[13]

In Glory and Agony: Isaac's Sacrifice and National Narrative, Yael Feldman argues that the story of Isaac's binding, in both its biblical and post-biblical versions (the New Testament included), has had a great impact on the ethos of altruist heroism and self-sacrifice in modern Hebrew national culture. As her study demonstrates, over the last century the "Binding of Isaac" has morphed into the "Sacrifice of Isaac," connoting both the glory and agony of heroic death on the battlefield.[14] In Legends of the Jews, Rabbi Louis Ginzberg argues that the binding of Isaac is a way for God to test Isaac's claim to Ishmael, and to silence Satan's protest about Abraham who had not brought up any offering to God after Isaac was born. It was also to show proof to the world that Abraham is a true God-fearing man who is ready to fulfill any of God's commands, even to sacrifice his own son:

When God commanded the father to desist from sacrificing Isaac, Abraham said: "One man tempts another, because he knoweth not what is in the heart of his neighbor. But Thou surely didst know that I was ready to sacrifice my son!"

God: "It was manifest to Me, and I foreknew it, that thou wouldst withhold not even thy soul from Me."

Abraham: "And why, then, didst Thou afflict me thus?"

God: "It was My wish that the world should become acquainted with thee, and should know that it is not without good reason that I have chosen thee from all the nations. Now it hath been witnessed unto men that thou fearest God."

— Legends of the Jews[15]

Jacob Howland has pointed out that "Ginzberg's work must be used with caution, because his project fabricating a unified narrative from multiple sources inevitably makes the tradition of rabbinic commentary seem more univocal than it actually is." Ginzberg's work does not encompass the way in which midrash on 'Akedah mirrored the different needs of diverse Jewish communities. Isaac was resurrected after the slaughter in the version of medieval Ashkenaz. Spiegel has interpreted this as designed to recast the biblical figures in the context of the Crusades.[16]

The Book of Genesis does not tell the age of Isaac at the time.[17] Some Talmudic sages teach that Isaac was an adult aged thirty seven,[15] likely based on the next biblical story, which is of Sarah's death at 127 years,[18] being 90 when Isaac was born.[19][20] Isaac's reaction to the binding is unstated in the biblical narrative. Some commentators have argued that he was traumatized and angry, often citing the fact that he and Abraham are never seen to speak to each other again; however, Jon D. Levenson notes that the biblical text never depicts them speaking before the binding, either.[21]

In the Genesis Apocryphon discovered in the Qumrannic Caves Scrolls (Dead Sea Scrolls) in 1946, Hebrew tribal patriarch Lamech, son of Methuselah converses with Abraham who also speaks in first and third person narratives.

Use in worship

[edit]The narrative of the sacrifice and binding of Isaac is traditionally read in synagogue on the second day of Rosh Hashanah.

The practice of the Kabbalists, observed in some communities but not all, is to recite this chapter every day immediately after Birkot hashachar.

Christian views

[edit]

The binding of Isaac is mentioned in the New Testament Epistle to the Hebrews among many acts of faith recorded in the Old Testament: "By faith Abraham, when he was tested, offered up Isaac, and he who had received the promises offered up his only begotten son, of whom it was said, 'In Isaac your seed shall be called', concluding that God was able to raise him up, even from the dead, from which he also received him in a figurative sense." (Hebrews 11:17–19, NKJV)[22]

Abraham's faith in God is such that he felt God would be able to resurrect the slain Isaac, in order that his prophecy (Genesis 21:12)[23] might be fulfilled. Early Christian preaching sometimes accepted Jewish interpretations of the binding of Isaac without elaborating. For example, Hippolytus of Rome says in his Commentary on the Song of Songs, "The blessed Isaac became desirous of the anointing and he wished to sacrifice himself for the sake of the world" (On the Song 2:15).[24]

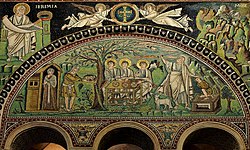

Other Christians from the period saw Isaac as a type of the "Word of God" who prefigured Christ.[25] This interpretation can be supported by symbolism and context such as Abraham sacrificing his son on the third day of the journey (Genesis 22:4),[26] or Abraham taking the wood and putting it on his son Isaac's shoulder (Genesis 22:6).[27] Another thing to note is how God reemphasizes Isaac being Abraham's one and only son whom he loves (Genesis 22:2, 12, 16).[28] As further support to the view of early Christians that the binding of Isaac foretells the Gospel of Jesus Christ, when the two went up there, Isaac asked Abraham "where is the lamb for the burnt offering" to which Abraham responded "God himself will provide the lamb for the burnt offering, my son." (Genesis 22:7–8).[29] However, it was a ram (not a lamb) that was ultimately sacrificed in Isaac's place, and the ram was caught in a thicket (i.e. thorn bush) (Genesis 22:13).[30] In the New Testament, John the Baptist saw Jesus coming toward him and said "Look, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world!" (John 1:29).[31] Thus, the binding is compared to the Crucifixion and the last-minute stay of sacrifice is a type of the Resurrection. Søren Kierkegaard describes Abraham's actions as arising from the zenith of faith leading to a "teleological suspension of the ethical".[32]

Francis Schaeffer argues:

Kierkegaard said this was an act of faith with nothing rational to base it upon or to which to relate it. Out of this came the modern concept of a 'leap of faith' and the total separation of rationality and faith. In this thinking concerning Abraham, Kierkegaard had not read the Bible carefully enough. Before Abraham was asked to move towards the sacrifice of Isaac (which, of course, God did not allow to be consummated), he had much propositional revelation from God, he had seen God, God had fulfilled promises to him. In short, God's words at this time were in the context of Abraham's strong reason for knowing that God both existed and was totally trustworthy.

— Francis A. Scaheffer, The God Who is There, 1990[33]

Muslim views

[edit]

The version in the Quran differs from that in Genesis in two aspects: the identity of the sacrificed son and the son's reaction towards the requested sacrifice. In Islamic sources, when Abraham tells his son about the vision, his son agreed to be sacrificed for the fulfillment of God's command, and no binding to the altar occurred. The Quran states that when Abraham asked for a righteous son, God granted him a son possessing forbearance.[34] The son mentioned here is traditionally understood to be Ishmael. When the son was able to walk and work with him, Abraham saw a vision about sacrificing him. When he told his son about it, his son agreed to fulfill the command of God in the vision. When they both had submitted their will to God and were ready for the sacrifice, God told Abraham he had fulfilled the vision, and provided him with a ram to sacrifice instead. God promised to reward Abraham.[35] Further verses state God also granted Abraham the righteous son Isaac and promised more rewards.[36][better source needed]

Among early Muslim scholars, there was a dispute over the identity of the son. One side of the argument believed it was Isaac rather than Ishmael (notably ibn Qutaybah and al-Tabari) interpreting the verse "God's perfecting his mercy on Abraham and Isaac" as referring to his making Abraham his closest one, and to his rescuing Isaac. The other side held that the promise to Sarah was of a son, Isaac, and a grandson, Jacob (Quran 11:71–74)[better source needed] excluded the possibility of a premature death of Isaac. Regardless, most Muslims believe that it is actually Ishmael rather than Isaac despite the dispute.[37]

The submission of Abraham and his son is celebrated and commemorated by Muslims on the days of Eid al-Adha. During the festival, those who can afford and the ones in the pilgrimage sacrifice a ram, cow, sheep or a camel. Part of the sacrifice meat is eaten by the household and the remainder is distributed to the neighbors and the needy. The festival marks the end of the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca.

Modern research

[edit]

The binding also figures prominently in the writings of several of the more important modern theologians, such as Søren Kierkegaard in Fear and Trembling and Shalom Spiegel in The Last Trial. Jewish communities regularly review this literature, for instance the 2009 mock trial held by more than 600 members of the University Synagogue of Orange County, California.[38] Derrida also looks at the story of the sacrifice as well as Kierkegaard's reading in The Gift of Death.

In Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, the literary critic Erich Auerbach considers the Hebrew narrative of the binding of Isaac, along with Homer's description of Odysseus's scar, as the two paradigmatic models for the representation of reality in literature. Auerbach contrasts Homer's attention to detail and foregrounding of the spatial, historical, as well as personal contexts for events to the Bible's sparse account, in which virtually all context is kept in the background or left outside of the narrative. As Auerbach observes, this narrative strategy virtually compels readers to add their own interpretations to the text.

Redactors and narrative purpose

[edit]Modern biblical critics operating under the framework of the documentary hypothesis have ascribed the binding's narrative to the biblical source Elohist, on the grounds that it generally uses the specific term Elohim (אלהים) and parallels characteristic E compositions. On that view, the second angelic appearance to Abraham (verses 14–18), praising his obedience and blessing his offspring, is in fact a later Jahwist interpolation to E's original account (verses 1–13, 19). This is supported by the style and composition of these verses, as well as by the use of the name Yahweh for the deity.[39]

More recent studies question the analysis of E and J as strictly separate. Coats argues that Abraham's obedience to God's command in fact necessitates praise and blessing, which he only receives in the second angelic speech.[40] That speech, therefore, could not have been simply inserted into E's original account. This has suggested to many that the author responsible for the interpolation of the second angelic appearance left their mark also on the original account (verses 1–13, 19).[39]

It has also been suggested that these traces are in fact the first angelic appearance (verses 11–12), in which the Angel of Yahweh stops Abraham before he kills Isaac.[41] The style and composition of these verses resemble that of the second angelic speech, and Yahweh is used for the deity rather than God. On that reading, in the original E version of the binding Abraham disobeys God's command, sacrificing the ram "instead of his son" (verse 13) on his own responsibility and without being stopped by an angel: "And Abraham stretched forth his hand, and took the knife to slay his son; but Abraham lifted up his eyes and looked and beheld, behind him was a ram, caught in a thicket by his horns; and Abraham went, and took the ram, and offered it up as a burnt offering instead of his son" (verses 10, 13).

By interpolating the first appearance of the angel, a later redactor shifted responsibility for halting the test from Abraham to the angel (verses 11–12). The second angelic appearance, in which Abraham is rewarded for his obedience (verses 14–18), became necessary due to that shift of responsibility. This analysis of the story sheds light on the connection between the binding and the story of Sodom (Genesis 18)[42] in which Abraham asks God whether he will destroy the city without distinguishing between the righteous and the wicked: "Far be it from you to do such a thing: Shall not the judge of all the earth do what is just?" According to this analysis, Abraham's question and conversation with God was a rebellion against him and culminates in Abraham's disobedience to God, refusing to sacrifice Isaac.[43]

Child sacrifice

[edit]

Francesca Stavrakopoulou said that it is possible that the story "contains traces of a tradition in which Abraham does sacrifice Isaac".[44] R. E. Friedman stated that in the original E story, Abraham may have carried out the sacrifice of Isaac, but that later repugnance at the idea of a human sacrifice led the redactor of JE to add the lines in which a ram is substituted for Isaac.[45] Likewise, Terence Fretheim wrote that "the text bears no specific mark of being a polemic against child sacrifice".[46] Wojciech Kosior also said that the genealogical snippet (Genesis 22:20–24) contain a hint to an alternative reading where Abraham sacrificed Isaac, since there would be no reason to list all these descendants of Abraham's brother.[47]

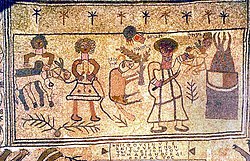

Interpretations of the text have contradicted the version where a ram is sacrificed. For example, Martin S. Bergmann stated "The Aggadah rabbis asserted that "father Isaac was bound on the altar and reduced to ashes, and his sacrificial dust was cast on Mount Moriah."[48] A similar interpretation was made in the Epistle to the Hebrews.[48] Margaret Barker said that "Abraham returned to Bersheeba without Isaac" according to Genesis 22:19,[49] a possible sign that he was indeed sacrificed.[50] Barker also said that wall paintings in the ancient Dura-Europos synagogue explicitly show Isaac being sacrificed, followed by his soul traveling to heaven.[50] According to Jon D. Levenson a part of Jewish tradition interpreted Isaac as having been sacrificed.[51] Similarly the German theologians Christian Rose [de] and Hans-Friedrich Weiß [de] said that due to the grammatical perfect tense used to describe Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac, he did, in fact, follow through with the action.[51]

Rav Kook, the first Chief Rabbi of Israel, said that the climax of the story, commanding Abraham not to sacrifice Isaac, is the whole point: to put an end to, and God's total aversion to, the ritual of child sacrifice.[52] According to Irving Greenberg the story of the binding of Isaac symbolizes the prohibition to worship God by human sacrifices, at a time when human sacrifices were the norm worldwide.[53]

Rite of passage

[edit]It has been suggested that Genesis 22 contains an intrusion of the liturgy of a rite of passage, including mock sacrifice, as commonly found in early and preliterate societies, marking the passage from youth to adulthood.[54]

Music

[edit]The Binding of Isaac has inspired multiple pieces of music, including Marc-Antoine Charpentier's Sacrificium Abrahae (H.402, oratorio for soloists, chorus, doubling instruments, and bc; 1680–81), Benjamin Britten's Canticle II: Abraham and Isaac, later adapted for inclusion in the War Requiem, Igor Stravinsky's Abraham and Isaac, Leonard Cohen's "Story of Isaac" from the 1969 album Songs from a Room,[55] and "You Want It Darker" from the 2016 album You Want it Darker, the eponymous "Highway 61 Revisited" from Highway 61 Revisited (1965) by Bob Dylan, Sufjan Stevens' "Abraham" from the album Seven Swans (2004), Gilad Hochman's "Akeda for Solo Viola" (2006), and Anaïs Mitchell's "Dyin Day" from the album Young Man in America (2012).

Wilfred Owen's poem "The Parable of the Old Man and the Young", set to music by Benjamin Britten in his War Requiem, ends with the couplet "But the old man would not so, but slew his son, And half the seed of Europe, one by one."[56]

Comparative

[edit]Greece: Toneia

[edit]The myth at the Heraion of Samos is that of Hera. According to the local tradition, the goddess was born under a lygos tree (Vitex agnus-castus, the "chaste-tree"). At the annual Samian festival called the Toneia, the "binding", the cult image of Hera was ceremonially bound with lygos branches, before being carried down to the sea to be washed. The tree still featured on the coinage of Samos in Roman times and Pausanias mentions that the tree still stood in the sanctuary.[57]

See also

[edit]- Child sacrifice

- Covenant of the pieces

- Eid al-Adha

- Fear and Trembling

- Filicide

- Iphigenia

- Jephthah's daughter

- Phrixus in Greek mythology, child sacrifice thwarted by ram

- Tophet

- Vayeira, the parashah containing the binding of Isaac

Notes

[edit]- ^ Genesis 22:2–8

- ^ Genesis 22:14

- ^ Genesis 22:2

- ^ Genesis 22:14

- ^ 2 Chronicles 3:1

- ^ Psalms 24:3

- ^ Isaiah 2:3

- ^ Isaiah 30:29

- ^ Zechariah 8:3

- ^ Porter, Stanley E. (2007-01-24). Porter (ed.). Dictionary of Biblical Criticism and Interpretation. Oxford, United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-134-63557-3.

- ^ Lippman Bodoff (2005). The Binding of Isaac, Religious Murders & Kabbalah: Seeds of Jewish Extremism and Alienation?. Devora Publishing. ISBN 978-1-932687-53-8. OCLC 1282116298.

- ^ Kahn, Ari (3 November 2014). "It Never Crossed my Mind". OU Torah.

- ^ Maimonides. The Guide of the Perplexed, Vol. 2, Book III, Ch. 24. English translation by Shlomo Pines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963.

- ^ Feldman, Yael S. (2010). Glory and Agony: Isaac's Sacrifice and National Narrative. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5902-1.

- ^ a b Ginzberg 1909.

- ^ Howland, Jacob (2015). "Fear and Trembling's 'Attunement' as midrash". In Conway, Daniel (ed.). Kierkegaard's Fear and Trembling. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Levenson, Jon D. (2004). "Genesis: introduction and annotations". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (eds.). The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195297515.

The Jewish study Bible.

- ^ Genesis 23:1

- ^ Genesis 17:17, 21

- ^ Jon D. Levenson, Lecture October 13, 2016: "Genesis 22: The Binding of Isaac and the Crucifixion of Jesus" Archived 2020-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, starting at about 1:05:10

- ^ Levenson, J. D. (2012). Inheriting Abraham: The Legacy of the Patriarch in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Library of Jewish Ideas. Princeton University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4008-4461-6. Archived from the original on 2019-06-15. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ Hebrews 11:17–19

- ^ Genesis 21:12

- ^ Smith, Yancy W. (2015-01-01). "Mystery of Anointing: Hippolytus' Commentary On the Song of Song in Social and Critical Contexts". Gorgias Studies in Early Christianity and Patristics.

- ^ Origen, Homilies on Genesis 12

- ^ Genesis 22:4

- ^ Genesis 22:6

- ^ Genesis 22:2–16

- ^ Genesis 22:7–8

- ^ Genesis 22:13

- ^ Genesis 1:29

- ^ Kierkegaard 1954.

- ^ Francis A. Schaeffer, "The God Who is There," in The Francis A. Schaeffer Trilogy: Three Essential Books in One Volume (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 1990), 15.1990

- ^ Quran 37:100-101

- ^ Quran 37:105

- ^ Quran 37:112–113

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Islam, Ishaq.

- ^ Bird, Cameron (12 January 2009). "For 'jury', a case of biblical proportions". The Orange County Register. Vol. 105, no. 12. p. 11.

- ^ a b G. J. Wenham. (1994). Genesis 16-50. Dallas, TX: Word Biblical Commentary.

- ^ Coats, G.W. (1973). Abraham's sacrifice of faith: A form critical study of Genesis 22. Interpretation, 27, pp. 389–400.

- ^ Boehm, O. (2002). The binding of Isaac: An inner Biblical polemic on the question of disobeying a manifestly illegal order. Vetus Testamentum, 52 (1) pp. 1–12.

- ^ Genesis 18

- ^ O. Boehm, O. (2007). The Binding of Isaac: A Religious Model of Disobedience, New York, NY: T&T Clark.

- ^ "It may be that the biblical story contains traces of a tradition in which Abraham does sacrifice Isaac, for in Genesis 22:19 Abraham appears to return from the mountain without Isaac". Stavrakopoulou, F. (2004). King Manasseh and child sacrifice: Biblical distortions of historical realities, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Friedman, R.E. (2003). The Bible With Sources Revealed, p. 65.

- ^ Terence E. Fretheim, in Marcia J. Bunge, Terence E. Fretheim, Beverly Roberts Gaventa (eds.), The Child in the Bible, p. 20

- ^ Kosior, Wojciech (2013). "'You have not withheld your son, your only one, from Me'. Some arguments for the consummated sacrifice of Abraham". The Polish Journal of the Arts and Culture. 8 (5/2013): 73–75. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ a b Bergmann, Martin S. (1992). In the Shadow of Moloch: The Sacrifice of Children and Its Impact on Western Religions, Volume 10. Columbia University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-231-07248-9. OCLC 1024062728.

- ^ Genesis 22:19

- ^ a b Barker, Margaret (27 September 2012). The Mother of the Lord: Volume 1: The Lady in the Temple. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-567-37861-3. OCLC 1075712859.

- ^ a b Morgan-Wynne, John Eifion (22 May 2020). Abraham in the New Testament. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 186–187. ISBN 978-1-72525-829-7. OCLC 1159564269.

- ^ "Olat Reiya", p. 93.

- ^ Irving Greenberg. 1988. The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays. New York: Summit Books. p.195.

- ^ T. McElwain (2005) The Beloved and I: New Jubilees Version of Sacred Scripture with Verse Commentaries pages 57–58.

- ^ "Songs From A Room – The Official Leonard Cohen Site". www.leonardcohen.com. Archived from the original on 2021-10-19. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- ^ "War Requiem: The complete text". Classic FM. Retrieved 2023-09-08.

- ^ Kyrieleis (1993) 135; Pedley (2005), 156-7; Pausanias 8.23.5

References

[edit]- Berman, Louis A. (1997). The Akedah: The Binding of Isaac. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1-56821-899-0.

- Bodoff, Lippman (2005). The Binding of Isaac, Religious Murders & Kabbalah: Seeds of Jewish Extremism and Alienation?. Devora Publishing. ISBN 1-932687-52-1.

- Bodofff, Lippman (1993). "The Real Test of the Akedah: Blind Obedience versus Moral Choice". Judaism. 42 (1).

- Bodofff, Lippman (1993). "God Tests Abraham – Abraham Tests God". Bible Review. IX (5): 52.

- Boehm, Omri (2002). "The Binding of Isaac: An Inner Biblical Polemic on the Question of Disobeying a Manifestly Illegal Order". Vetus Testamentum. 52 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1163/15685330252965686.

- Boehm, Omri (2007). The Binding of Isaac: A Religious Model of Disobedience. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-02613-2.

- Delaney, Carol (1998). Abraham on Trial. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05985-3.

- Delaney, Carol (1999). "Abraham, Isaac, and Some Hidden Assumptions of Our Culture". The Humanist. May/June. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2015-02-02.

- Feiler, Bruce (2002). Abraham: A Journey to the Heart of Three Faiths. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-083866-3.

- Feldman, Yael (2010). Glory and Agony: Isaac's Sacrifice and National Narrative'. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5902-1.

- Firestone, Reuven (1990). Journeys in Holy Lands: The Evolution of the Abraham-Ishmael Legends in Islamic Exegesis. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-0332-7.

- Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews Vol. I : Satan Accuses Abraham (PDF). Translated by Henrietta Szold. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. Archived from the original on 2020-03-13. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- Goodman, James (2015). Abraham and His Son: The Story of a Story. Sandstone Press. ISBN 978-1-910124-15-4.

- Goodman, James (2013). But Where Is the Lamb? Imagining the Story of Abraham and Isaac. Schocken Books. ISBN 978-0-8052-4253-9.

- Jensen, Robin M. (1993). "The Binding or Sacrifice of Isaac: How Jews and Christians See Differently". Bible Review. 9 (5): 42–51.

- Kierkegaard, Søren (1954). Fear and Trembling. Anchor Books.

- Levenson, Jon D. (1995). The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son: The Transformation of Child Sacrifice in Judaism and Christianity. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06511-6.

- Ravitzky, Aviezer. Abraham: Father of the Believers (in Hebrew). Hebrew University.

- Sarna, Nahum (1989). The JPS Torah Commentary: Genesis. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 0-8276-0326-6.

- Spiegel, Shalom (1967). The Last Trial: On the Legends and Lore of the Command to Abraham to Offer Isaac As a Sacrifice: The Akedah (1993 reprint ed.). Jewish Lights Publishing. ISBN 1-879045-29-X.

External links

[edit]- Symposium on the Sacrifice of Isaac in the Three Monotheistic Religions

- The Sacrifice of Isaac in Medieval English Drama

- Mystery play texts in the cycles from Chester, Wakefield,[permanent dead link] York,[permanent dead link] and n-Town; Archived 2008-03-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Shofar Callin' (G-dcast's animated retelling of the Binding of Isaac, to a hip hop soundtrack)

KSF

KSF