Birmingham Terminal Station

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 9 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 9 min

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2013) |

Birmingham Terminal Station | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

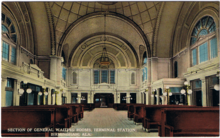

Hand colored postcard from a photograph of the Birmingham Terminal Station taken in 1909 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Construction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architect | P. Thornton Marye | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1909 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closed | 1969 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Key dates | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1969 | demolished | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former services | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Birmingham Terminal Station (or simply Birmingham Terminal), completed in 1909, was the principal railway station for Birmingham, Alabama (United States) until the 1950s. It was demolished in 1969, and its loss still serves as a rallying image for local preservationists.

Beginnings

[edit]Six of the seven railroads serving Birmingham joined to create the Birmingham Terminal Company in the early 20th century. They funded a new $2 million terminal station covering two blocks of the city at the eastern end of 5th Avenue North downtown. The station largely took over the function of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad station at Morris Avenue and 20th Street. Thus, the Louisville and Nashville and the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad maintained their own respective stations, separate from Terminal Station.

Architecture

[edit]

The architect for the hulking Byzantine-inspired Beaux-Arts station was P. Thornton Marye of Washington, D.C. The exotic design stirred controversy at first.

The exterior of the building was primarily dressed in light-brown brick. Two 130-foot (40 m) towers topped the north and south wings. The central waiting room covered 7,600 square feet (710 m2) and was covered by a central dome 64 feet (20 m) in diameter covered in intricate tilework and featuring a skylight of ornamental glass. The bottom 16 feet (4.9 m) of the walls in the main waiting room were finished in gray Tennessee marble.

Connecting to the main waiting room were the ticket office, a separate ladies' waiting room, a smoking room, a barber shop, a news stand, a refreshment stand, and telephone and telegraph booths. Along the north and south concourses were the kitchen, lunch and dining rooms, another smoking room, restrooms, and the "colored" waiting room, a requirement of Birmingham's strict racial segregation. The north wing housed two express freight companies while the south was used for baggage and mail transfer.

Outside of the station were ten tracks. A series of overlapping "umbrella" sheds covered the platforms and tracks. These sheds provided protection from the rain while still letting in sunlight and fresh air. During the Depression, the station fell into disrepair, but resurged in the late 1930s through World War II. In 1943 the station underwent a $500,000 renovation which included sandblasting, new paint, and new interior fixtures. During this period of rebirth, rail traffic peaked at 54 trains per day.

Passenger services

[edit]The station's tenants included the Central of Georgia, Illinois Central, St. Louis-San Francisco ('Frisco'), Seaboard Air Line and Southern Railway.[1]

Major named passenger trains included:[2][3][4][5]

- Central of Georgia and Illinois Central:

- City of Miami (Chicago-Miami)

- Seminole (Chicago-Jacksonville)

- St. Louis-San Francisco, and Southern Railway:

- Kansas City-Florida Special (Kansas City-Jacksonville)

- Sunnyland (Memphis-Atlanta)

- Seaboard Air Line:

- Cotton Blossom: New York - Birmingham

- Passenger Mail and Express: Washington and Portsmouth - Birmingham

- Silver Comet: New York and Portsmouth - Birmingham

- Southern Railway:

- Birmingham Special (New York City-Birmingham)

- Pelican (New York City-New Orleans)

- Southerner (New York City-New Orleans)

Decline

[edit]

As automobile ownership increased and air travel gained popularity, rail travel suffered. By 1960 only 26 trains per day went through Terminal Station. At the beginning of 1969 it was down to seven trains. During the 1960s the station served as the site of numerous small episodes of the Civil Rights Movement. Local Civil Rights leaders like Fred Shuttlesworth challenged the racially segregated accommodations of the station and crowds of belligerent whites gathered, sometimes leading to violence.

In 1969 the U.S. Social Security Administration announced plans to build a consolidated service center in downtown Birmingham. William Engel of Engel Realty quietly put together a plan for a $10 million redevelopment for the site of the deteriorating station. The redevelopment, which Engel pitched to the Southern Railway, would include a smaller and more modern train terminal along with a new Social Security building, two smaller office buildings and a large hotel.

Permission to proceed with demolition was granted on June 30, 1969 by the Alabama Public Service Commission. They set aside the arguments of numerous local preservationists in attendance (including the Heart of Dixie Railroad Society, the Alabama Historical Society, the Women's Committee of 100 and number of prominent local architects) stating that they may only consider "the necessity and convenience of the traveling public." In its run-down state, the Terminal Station was judged to no longer meet those needs. Within a few months, the building was demolished by the T. M. Burgin Demolition Company and the site cleared.

Ultimately the redevelopment plans were never built. The Social Security Administration built a new office building elsewhere in 1974. The site became part of the right-of-way for the Red Mountain Expressway, connecting U.S. Highway 31 and U.S. Highway 280 with Interstate 20 and Interstate 59. By using the Terminal Station site, a public housing project which had been slated for demolition, was preserved. The Southern Railroad moved their passenger station two blocks north to Seventh Avenue, using that site until 1979, when the Southern Crescent was rerouted along the Louisville & Nashville right-of-way by Amtrak.

5th Avenue North tunnel

[edit]An underpass, locally called a "subway" tunneled below the center of the building, allowing streetcars to bypass the terminal and rail traffic. In 1926 a large electric sign reading "Welcome to Birmingham, the Magic City", was erected outside the station at the west end of the underpass. The sign functioned as a gateway for visitors who arrived primarily by rail and 5th Avenue became a "hotel row", lined with restaurants and entertainments. The only remnant of the demolished building to survive after 1969 was the tunnel, now commonly known as the 5th Avenue North tunnel, which now carries that road under the highway and railroad tracks.

References

[edit]- ^ "Index of Railway Stations, p. 1276". Official Guide of the Railways. 87 (7). National Railway Publication Company. December 1954.

- ^ "Central of Georgia, Table 5". Official Guide of the Railways. 87 (7). National Railway Publication Company. December 1954.

- ^ "Illinois Central, Tables B, 4". Official Guide of the Railways. 87 (7). National Railway Publication Company. December 1954.

- ^ "St. Louis-San Francisco Railway, Table 3". Official Guide of the Railways. 87 (7). National Railway Publication Company. December 1954.

- ^ "Southern Railway, Tables D, F, G". Official Guide of the Railways. 87 (7). National Railway Publication Company. December 1954.

External links

[edit]- Terminal Station at BhamWiki.com (archived) - accessed October 24, 2006

- Kelly, Mark (May 28, 1998) "Terminated Station: The Rise and Fall of Birmingham's Terminal Station". Black & White, pp. 14–17.

33°31′21″N 86°47′57″W / 33.52245°N 86.79908°W

- Clemons, Marvin, "Great Temple of Travel: A Pictorial History of Birmingham Terminal Station, 1909-1969," MidSouth Media, 2016

KSF

KSF