Black Futures

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 5 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 5 min

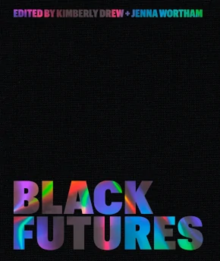

First edition cover | |

| Author | Kimberly Drew, Jenna Wortham, eds. |

|---|---|

| Publisher | One World |

Publication date | December 1, 2020 |

| Pages | 544 |

| ISBN | 9780399181139 |

Black Futures is an American anthology of Black art, writing, and other creative work, edited by writer Jenna Wortham and curator Kimberly Drew. Writer Teju Cole, singer Solange Knowles and activist Alicia Garza, who cofounded Black Lives Matter, are among the book's more than 100 contributors. The 544-page collection was published in 2020, receiving strongly favorable reviews.

Development and publication

[edit]Beginning their collaboration in 2015, New York Times writer Jenna Wortham and curator and activist Kimberly Drew aimed to record the way "communities of Black people [were] interacting and engaging in new ways because of social media ... creating our own signage and language," Wortham said.[1] They originally conceived of creating a zine, but ultimately concluded the accessibility technology available for books would allow more people to engage with the work.[2][1]

The 544-page collection,[3] designed by Wael Marcos and Jonathan Key,[2] was published on December 1, 2020[3] by One World, publisher Chris Jackson's imprint at Penguin Random House.[4]

Content

[edit]The 544-page anthology,[5] collecting works of more than 100 contributors,[6] includes discussions, like writer Rembert Browne and filmmaker Ezra Edelman on Colin Kaepernick, as well as works, for example artist Yetunde Olagbaju's "I Will Protect Black People" contract.[2] In addition to traditional media such as painting and essays, Black Futures includes creative works in the form of recipes,[7] Instagram posts, tweets, street art, and communal gatherings.[4] These are organized by theme, included "Justice", "Power", "Joy", "Black is (Still Beautiful)", "Memory", and "Legacy".[8]

Other contributors include activist Alicia Garza (co-founder of Black Lives Matter), writer Morgan Parker, comedian Ziwe Fumudoh, writer Teju Cole and singer Solange Knowles.[9]

Reception

[edit]Black Futures received enthusiastic reviews, beginning with a starred review in Kirkus.[5] Writing in The Root, Maiysha Kai called Black Futures "a weighty and gorgeously bound compendium of Black creativity".[10]

Reviews emphasized the scope of the collection. In Interview, Black Futures was compared to Toni Morrison's 1974 work The Black Book, which covered Black American life from 1619 (the year the first enslaved Africans were brought to territory now part of the United States) to Morrison's writing in the mid-20th century: "it filled such a gap in the library that an entire wing should have been built just to hold it".[11] Beyond sheer breadth, critics emphasized the book's expansive quality of Black Futures's structure and aesthetic sensibility. In The New York Times, Scaachi Koul found the book "a literary experience unlike any I've had in recent memory", distinguished by the way "you can enter and exit the project on whatever pages you choose...once you start reading 'Black Futures,' you are somehow endlessly reading it".[12] Koul notes that Wortham and Drew recommend reading with an internet-connected device at hand, to follow threads the book offers out into the world. The book's "brief chapters reach in seemingly infinite directions, each one a portal into what could be an entire book on its own".[12] Writing in the Chicago Review of Books, Mandana Chaffa agreed Black Futures is "a jumping off point for discussion, rather than a static destination", something to be used as a "divinatory tool": "open anywhere [...] and see where it leads [...] like the best of parties, in which you come across those familiar to you, and through them, new, thought-provoking voices".[8]

For Koul, who is not Black, the cumulative experience creates a call to action—"a question any non-Black person inevitably comes back to again and again throughout the book: If you know the fight, will you join it?" Publishers Weekly also emphasized this effect, "This unique and imaginative work issues a powerful call for justice, equality, and inclusion".[3] But Koul also noted that struggle was not the only Black experience documented, and as a non-Black reader she felt grateful "to be let in on [the book's] moments of joyous intimacy. You feel thankful for being offered entry".[12]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Marius, Marley (December 2020). "Jenna Wortham and Kimberly Drew's "Black Futures" Reflects a Cultural Revolution". Vogue. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c Diop, Arimeta (November 17, 2020). "Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham Look Toward the Future". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on November 17, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Black Futures". Publishers Weekly. September 1, 2020. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Bollen, Christopher (October 28, 2020). "Chris Jackson on Why the Status Quo is Killing Us". Interview Magazine. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "BLACK FUTURES". Kirkus Reviews. November 5, 2020. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Sullivan, Mecca Jamilah (December 1, 2020). "Ntozake Been Said That". The Cut. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Brara, Noor (October 7, 2020). "The New Innovators: Writer and Curator Kimberly Drew on Why the Stodgy Old Art World Is Finally Opening Up to New Ideas". artnet News. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Mandana Chaffa (December 4, 2020). "The Multitudes and Multiverse of "Black Futures"". Chicago Review of Books. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Khatib, Joumana (November 25, 2020). "7 New Books to Watch For in December". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Kai, Maiysha (November 27, 2020). "The Root Presents It's Lit! Goes Black to the Future With Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham". The Root. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ "Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham Talk to Janicza Bravo About "Black Futures"". Interview Magazine. December 1, 2020. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c Koul, Scaachi (November 30, 2020). "A Peek at the Variety, Wonder and Trauma of Black Life, Then and Now". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Excerpt in the October 7, 2020 issue of the New York Times Magazine

- An early Black Futures selection for Walker Art Center by Wortham and Drew, December 23, 2015

KSF

KSF