Blood–testis barrier

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 7 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 7 min

| Blood–testis barrier | |

|---|---|

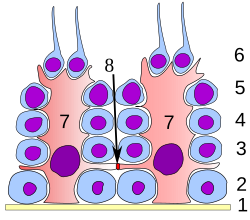

Germinal epithelium of the testicle. 1 basal lamina, 2 spermatogonia, 3 spermatocyte 1st order, 4 spermatocyte 2nd order, 5 spermatid, 6 mature spermatid, 7 Sertoli cell, 8 tight junction (blood testis barrier) | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D001814 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The blood–testis barrier is a physical barrier between the blood vessels and the seminiferous tubules of the animal testes. The name "blood-testis barrier" is misleading as it is not a blood-organ barrier in a strict sense, but is formed between Sertoli cells of the seminiferous tubule and isolates the further developed stages of germ cells from the blood. A more correct term is the Sertoli cell barrier (SCB).

Structure

[edit]The walls of seminiferous tubules are lined with primitive germ layer cells and by Sertoli cells.[1] The barrier is formed by tight junctions, adherens junctions and gap junctions between the Sertoli cells, which are sustentacular cells (supporting cells) of the seminiferous tubules, and divides the seminiferous tubule into a basal compartment (outer side of the tubule, in contact with blood and lymph) and an endoluminal compartment (inner side of the tubule, isolated from blood and lymph). The tight junctions are formed by intercellular adhesion molecules in between cells that are anchored to actin fibers within the cells. For the visualization of the actin fibers within the seminiferous tubules see Sharma et al.'s immunofluorescence studies.[2]

Function

[edit]The presence of the SCB allows Sertoli cells to control the adluminal environment in which germ cells (spermatocytes, spermatids and sperm) develop by influencing the chemical composition of the luminal fluid. The barrier also prevents passage of cytotoxic agents (bodies or substances that are toxic to cells) into the seminiferous tubules.

The fluid in the lumen of seminiferous tubules is quite different from plasma; it contains very little protein and glucose but is rich in androgens, estrogens, potassium, inositol and glutamic and aspartic acid. This composition is maintained by blood–testis barrier.[1]

The barrier also protects the germ cells from blood-borne noxious agents,[1] prevents antigenic products of germ cell maturation from entering the circulation and generating an autoimmune response,[1] and may help establish an osmotic gradient that facilitates movement of fluid into the tubular lumen.[1]

Note

[edit]Steroids penetrate the barrier. Some proteins pass from Sertoli cells to Leydig cells to function in a paracrine fashion.[1]

Clinical significance

[edit]Auto-immune response

[edit]The blood–testes barrier can be damaged by trauma to the testes (including torsion or impact), by surgery or as a result of vasectomy. When the blood–testes barrier is breached, and sperm enters the bloodstream, the immune system mounts an autoimmune response against the sperm, since the immune system has not been tolerized against the unique sperm antigens that are only expressed by these cells. The anti-sperm antibodies generated by the immune system can bind to various antigenic sites on the surface of the developing sperm within the testes. If they bind to the head, the sperm may be less able to fertilize an egg, and, if they bind to the tail, the motility of the sperm can be reduced.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Blood–air barrier – Membrane separating alveolar air from blood in lung capillaries

- Blood–brain barrier – Semipermeable capillary border that allows selective passage of blood constituents into the brain

- Blood–ocular barrier – Physical barrier between the local blood vessels and most parts of the eye itself

- Blood–retinal barrier – Part of the blood–ocular barrier that prevents certain substances from entering the retina

- Blood–saliva barrier – Semipermeable biological barrier

- Blood–thymus barrier – Barrier formed by the continuous blood capillaries in the thymic cortex

- Spermatogenesis – Production of sperm

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Barrett KE, Barman SM, Boitano S, Brooks H (2012). Ganong's Review of Medical Physiology 24th Edition. McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 419–20. ISBN 978-1-25-902753-6.

- ^ Sharma S, Hanukoglu A, Hanukoglu I (April 2018). "Localization of epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and CFTR in the germinal epithelium of the testis, Sertoli cells, and spermatozoa". J. Mol. Histol. 49 (2): 195–208. doi:10.1007/s10735-018-9759-2. PMID 29453757. S2CID 3761720.

External links

[edit]- Blood-testis+barrier at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview at okstate.edu

KSF

KSF