Boosterism

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 6 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 6 min

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (July 2018) |

Boosterism is the act of promoting ("boosting") a town, city, or organization, with the goal of improving public perception of it. Boosting can be as simple as talking up the entity at a party or as elaborate as establishing a visitors' bureau.

History

[edit]Greenland is claimed to owe its name to an act of boosterism. The Saga of Erik the Red states that Erik the Red named the island "Greenland" because "men will desire much the more to go there if the land has a good name."[1]

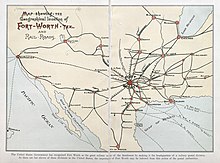

During the expansion of the American and Canadian West, boosterism became epidemic as the leaders and owners of small towns made extravagant predictions for their settlement, in the hope of attracting more residents and, not coincidentally, inflating the prices of local real estate. During the nineteenth century, competition for economic success among newly founded cities led to overflow of booster literature that listed the visible signs of growth, cited statistics on population and trade and looked to local geography for town success reasons.[2]

The 1871 humorous speech The Untold Delights of Duluth, delivered by Democratic U.S. Representative J. Proctor Knott, lampooned boosterism. Boosterism is also a major theme of two novels by Sinclair Lewis—Main Street (published 1920) and Babbitt (1922). As indicated by an editorial that Lewis wrote in 1908 entitled "The Needful Knocker", boosting was the opposite of knocking. The editorial explained:

The booster's enthusiasm is the motive force which builds up our American cities. Granted. But the hated knocker's jibes are the check necessary to guide that force. In summary then, we do not wish to knock the booster, but we certainly do wish to boost the knocker.[3][4]

The short story "Jeeves and the Hard-boiled Egg" (1917) by P.G. Wodehouse includes an encounter with a convention visiting from the fictional town of Birdsburg, Missouri who talk up their town:

"You should pay it a visit," he said. "The most rapidly-growing city in the country. Boost for Birdsburg!" "Boost for Birdsburg!" said the other chappies reverently.

Boosting is also done in political settings, especially in regard to disputed policies or controversial events. The former UK prime minister Boris Johnson is strongly associated with such behaviour.[5][6][7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Eirik The Red's Saga:, by The Rev. J. Sephton". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2024-10-13.

- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 46.

- ^ Fionola Meredith (June 7, 2012). "Don't let punks become PR men just to reel in tourists". Belfast Telegraph.

- ^ Quoted in Schorer, M.: Sinclair Lewis: An American Life, page 142. McGraw-Hill, 1961.

- ^ Crace, John (5 January 2021). "Boris's boosterism means he never learns". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Eliot (7 October 2021). "Is the long-suffering public beginning to tire of jocular 'boosterism'?". The Telegraph.

- ^ Druty, Colin (6 October 2021). "Boris the booster: Worksop ponders PM speech long on laughs but short on reality". The Independent.

External links

[edit]- The Promised Land, by Pierre Berton

- Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis

- The Untold Delights of Duluth, a speech by a US congressman in 1871, introduced by David McCullough

KSF

KSF