British Military Administration (Malaya)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 20 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 20 min

British Military Administration of Malaya | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945–1946 | |||||||||||||||||||

The Empire of Japan surrendered to the British Empire in Kuala Lumpur in 1945. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Interim military administration | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Kuala Lumpur (de facto) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Post-war | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2 September 1945 | |||||||||||||||||||

• British Military Administration established | 12 September 1945 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Formation of Malayan Union | 1 April 1946 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Malayan dollar British Pound | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||

| History of Malaysia |

|---|

|

|

|

The British Military Administration (BMA) was the interim administrator of British Malaya from August 1945, the end of World War II, to the establishment of the Malayan Union in April 1946. The BMA was under the direct command of the Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia, Lord Louis Mountbatten. The administration had the dual function of maintaining basic subsistence during the period of reoccupation, and also of imposing the state structure upon which post-war imperial power would rest.[1]

Background

[edit]

Prior to the Japanese occupation, British Malaya was divided into Federated and Unfederated states, and the Straits Settlements. In the 1930s, Edward Gent of the British Colonial Office was in favour of bringing these separate elements closer together. After the Japanese occupation, the British began to consider how to reconquer Malaya and reestablish colonial administration. The planning for the new administration was handled by the Civil Affairs, Malaya Planning Unit (CAMPU) and the Eastern Department of the Colonial Office under Gent. The first phase was to be a Military Administration that returned stability followed by a Malay Union that would bring together all the states under a single government to secure Britain's possessions in Malaya.[2]

By early 1945, the British had plans to invade Malaya on 9 September under the code name Operation Zipper. However, the Japanese surrendered on 15 August, weeks before the planned invasion. As a result, British arrangements for a gradual re-establishment of colonial administration over Malaya and the other territories were now obsolete and a vast area including Malaya, Singapore, Indonesia, British North Borneo, Indo-China, Sarawak, and Hong Kong was free from colonial control.[3]

In the period between the Japanese emperor's announcement and the arrival of Allied forces in Malaya, the Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army focused its efforts on seizing control of territory across Malaya and punishing "collaborators" of the Japanese regime.[4] A few of the Japanese occupation troops also came under attack from civilians during this period as they withdrew from outlying areas and some defected to the MPAJA.

Condition of Japanese-occupied Malaya

[edit]During the initial period of the Japanese occupation the Ethnic Chinese in Malaya were ill-treated by the Japanese because of their support for China in the Second Sino-Japanese War. Malaya's two other major ethnic groups, the Indians and Malays, escaped the worst of the initial Japanese maltreatment. The Japanese wanted the support of the Indian community to free India from British rule. They also considered the Malays not to be a threat. All three races were encouraged to assist Japanese war efforts by providing finance and labour. Some 73,000 Malayans were thought to have been coerced into work on the Thai-Burma Railway, with an estimated 25,000 dying. The Japanese also took the railway track from Malacca and other branch lines for construction of the Siam-Burma railway.

About 150,000 tons of rubber was taken by the Japanese, but this was considerably less than Malaya exported prior to the occupation. Because Malaya produced more rubber and tin than Japan was able to utilize Malaya lost its export income. Real per capita income fell to about half its 1941 level in 1944 and less than half the 1938 level in 1945.[5]

Prior to the war Malaya produced 40% of the world's rubber and a high proportion of the world's tin. It imported more than 50% of its rice requirements, a staple food for its population. The Allied blockade meant that both imports and the limited exports to Japan were dramatically reduced.[6]

During the occupation the Japanese replaced the Malayan dollar with their own version.[7] Prior to occupation, in 1941, there was about Malaya $219 million in circulation. Japanese currency officials estimated that they had put $7,000 to $8,000 million into circulation during occupation. Some Japanese army units had mobile currency printing presses and no record was kept of the quantity or value of notes printed. When Malaya was liberated there was $500 million of uncirculated currency held by the Japanese in Kuala Lumpur. The unrestrained printing of banknotes in the final months of the war created hyperinflation with the Japanese money becoming valueless at the end of the war.

During the war the Allies dropped propaganda leaflets stressing that the Japanese issued money would be valueless when Japan surrendered. This tactic was suggested by Japanese policy makers as one of the reasons for the currencies falling value as Japanese defeats increased. Although a price freeze was put in place in February 1942, by the end of the war prices in Malaya were 11,000 times higher than at the start of the war. Monthly inflation reached over 40% in August 1945.[8][5] Counterfeiting of the currency was also rife with both the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) printing $10 notes and $1 notes and the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) printing $10 notes.[9]

Because of Allied blockades against the Japanese, Malaya was short of food and medical supplies by the end of the war.[6]

British return

[edit]

Under Operation Jurist, Penang became the first state in Malaya to be liberated from Japanese rule. The Japanese garrison in Penang formally surrendered on 2 September 1945 aboard HMS Nelson and a party of the Royal Marines retook Penang Island the following day. The British subsequently occupied Singapore, with the Japanese garrison on the island formally surrendering on 12 September. The same day the BMA was installed in Kuala Lumpur. This was followed by the signing of the Malaya surrender document at Kuala Lumpur by Lieutenant-General Teizo Ishiguro, commander of the 29th Army; with Major-General Naoichi Kawahara, Chief of Staff; and Colonel Oguri as witnesses. Another surrender ceremony was held in Kuala Lumpur on 22 February 1946 for General Seishirō Itagaki, the Commander of the 7th Area Army. The British re-occupation of Malaya included the four northern Malay states occupied by Thailand in 1943. It also gradually brought back into force the laws that had been in force prior to the Japanese occupation.

BMA established

[edit]The BMA was established on 15 August 1945 by Proclamation No 1 of the Supreme Allied Commander of Southeast Asia. The BMA assumed full judicial, legislative, executive and administrative powers and responsibilities and conclusive jurisdiction over all persons and property throughout Malaya including Singapore. Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten became the Director of the Administration in September 1945. Lieutenant General Philip Christison was appointed General Officer Commanding British forces in Malaya.[10] Major-General Ralph Hone was given the post of Chief Civil Affairs Officer Malaya (CCAO(M)) responsible for the territory of Malaya.[11]: 113 Further proclamations:

- disestablished Japanese tribunals were disestablished and replaced by military courts, a Superior Court to deal with people charged with offences against the laws and usages of war and military related offences, and a District Court to try criminal cases and inquiries into death;

- prohibited the sale of alcohol and civilian foodstuffs to members of the armed forces;

- made the former Malayan currency legal tender and effectively made the Japanese circulated currency worthless;[12] and

- covered the safety of British and Allied Forces and the maintenance of public order and safety. Notices publicizing these also noted that the BMA was temporary in nature.[10]

- a moratorium was placed on all dealings in land and all financial institutions were closed.[13]

For the purpose of streamlining the administration and in preparation for the proposed Malayan Union, postwar Malaya was divided into 9 regions with Perlis-Kedah, Negeri Sembilan-Melaka, and the other states as regions in their own right. The regions were controlled by a Senior Civil Affairs Officer (ranked either Colonel or Lieutenant-Colonel). Earlier, the planning for civil affairs in the Malayan Peninsula was done by the Deputy Chief Civil Affairs Officer, Brigadier H C Willan. The Federal Secretariat in Kuala Lumpur hosted the Civil Affairs Headquarters. In October 1945 this office was merged with the office of the Chief Civil Affairs Officer.[14]

Given the military nature of the administration, the official power of some of the pre-war civilian governments' entities were suspended, including the rights of the Malay sultanate rulers. Civil Affairs Officers also acted in the capacity of District Officers. Colonel John G. Adams of the London Irish Rifles (previously injured in action during the Sicilian campaign on the Catania plains) was selected as the President of the Superior Court in 1945.[citation needed]

Personnel

[edit]Although its name (British Military Administration) implies the BMA was primarily a military organisation. However there were civilian advisers and many of the military officials were civilians in uniform, it too often appeared indifferent to popular concerns. A complication factor was that the BMA had few seasoned professional administrators on whom to call.[15] Nearly three-quarters of the senior staff had no previous experience in government and only a quarter of the Civilian Affairs senior staff had any knowledge of Malaya.[16] Further, the armed component of the BMA was a source of innumerable complaints. As a British observer noted, "In general the Army behaved, and this goes for the officers also, as if they were in conquered enemy territory'.[17]

Reoccupation

[edit]Penang was the first part of Malaya liberated from Japanese rule on 3 September by the Royal Marines. The first Allied troops into Johore were the 123rd Brigade of the 5th Indian Division on 7 September. They set up base near the causeway at Johor Bahru. The same day the West Yorkshire Regiment began occupying Klang in Selangor.[18]

Issues facing the BMA

[edit]On arrival the BMA faced a range of issues requiring its immediate attention. These included the detention and disarming of the Japanese military, the identification and trial of war criminals, the release and repatriation of prisoners of war, the repair of key infrastructure, enabling the re-establishment of key industries, the disarming and repatriation of guerrilla armies including the MPAJA, the re-establishment of the rule of law, and the distribution of food and medical supplies.

The abolition of banana money meant that in the immediate period following re-occupation there was no legal currency in circulation, except for some pre-war currency kept by a few.[19]

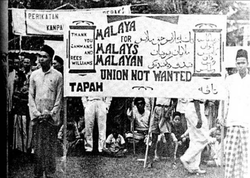

Further complicating matters pre-War British colonial administrations had adhered to a strict code of behaviour, and thus corruption had been virtually absent.[15]: 13 Under the Japanese, however, bribery, smuggling, extortion, black market dealings, and other unsavory habits had become a way of life and were much too ingrained to be changed without a strenuous effort once the British returned. The Japanese had also used the slogan Malaya for the Malays as part of their war time propaganda raising with it a desire for independence from Colonial government.[15]: 14 There were also significant racial divisions originating from the pre-war colonial period and exacerbated by the initial harsh treatment of Chinese population by the Japanese in comparison to the Malay and Indian populations, attacks and reprisals against Malays by the predominantly Chinese MPAJA, resentment by Malay's against Chinese and to a lesser extent Indian communities who were perceived as exploiting them and their country, and significant religious, cultural, and language differences between the races.[20]

One aspect the military government might have been expected to be most successful- that of ensuring personal security- they were found wanting..[citation needed] Firstly, the BMA were incapable of curbing what was widely referred to as 'gangsterism'.[15]: 15 Over 600 murders reported between 1945 and 1948, and it was generally acknowledged that the actual total was much higher.[21] Kidnapping and extortion were common throughout the Peninsula, as was piracy along the west coast. The overall crime rate in the Peninsula further fuelled resentment against the administration, which did little to curb crime and restore law and order.[citation needed]

Through the personnel make up and economic policies of the BMA, one may see they were in no good position of winning back the hearts and minds of the Malayan peoples. Except for the first few days after they returned to Malaya, the British never really regained the confidence of the general public. Failure to win the hearts and minds of Malayans would lead to other developments, for example the rise of the Malayan Communist Party.[citation needed]

Economic Policies

[edit]The greatest initial challenge of authority for the British Military Administration was its capacity to re-introduce and re-enforce order in trade and employment in the aftermath of Japanese surrender and departure. The destruction of the pre-War infrastructure was not conducted by the Japanese alone, rather the British use of a "scorched earth" policy as they retreated down the Peninsula in 1942.[citation needed]

From the onset it because quite clear that the British government in the metropole would not provide funds in the reconstruction of Malaya. Of course, Malaya was fortunate to have been saved from further destruction by the sudden surrender of the Imperial Japanese Army, but the damage already done was considerable. It was estimated, for example, that $105 million would be needed to restore that railway infrastructure to its pre-War condition.[11] In addition, within a few days after the British arrived in Malaya, it was announced that the Japanese currency, or 'Banana money' as it was called, was 'worth no more than the paper on which it is printed'.[15]: 13 This led to a drastic shortage of currency, nobody had any money to buy necessities such as food and fuel. Individual savings which had been carefully accumulated during the war years were completely wiped out overnight. This unsurprisingly created an increase of tension between the local populace and the BMA..[citation needed]

The BMA further set controls on currency payments for imported goods, goods imported from the US for example still had to paid in sterling or were under heavy restriction. This policy of the BMA was not of its own choice, it was a policy of the then Secretary of State for the Colonies. This policy was categorised as 'a regime of war time austerity as regards imports'.[22] Only goods that were considered essential could be imported from outside the sterling area (Canada, Great Britain, Australia). This resulted in acute shortages of important supplies and machinery which in turn hampered Malaya's economic growth. Lastly, the sale price of key commodities were set by the British government in London and enforced by the BMA. The key commodities were rubber, tin and to a lesser extent timber. The artificially and unrealistically low prices were considered by most producers as unacceptable.[15]: 18 Hence, after the return of the British, the economic strategy of the British and to a lesser extent the Malayan government exasperated the country's business leaders. In particular. Malayan businessmen (ethnic Chinese) were greatly dissatisfied with the economic policies. It was felt by the local population that British interests were placed high above the interests of Malaya.[15]: 19

Prelude to Malayan Union

[edit]

In May 1943 the Colonial Office began to consider how Malaya should be administered after the war. A plan was formulated in which the Federated and Unfederated Malay States, along with the Straits Settlements (excluding Singapore) were to be merged into a single entity called the Malayan Union. Included in the proposed union was the removal of political power from the sultans and granting of citizenship to non-Malays who had been resident in Malaya for at least 10 out of 15 years prior to 15 February 1942.[23][24]

The proposal was announced on 10 October 1945 by George Hall, Secretary of State for the Colonies. Sir Harold MacMichael was empowered to sign revised treaties with the Malay sultans to enable the Union to proceed. MacMichael made several visits to the Malay rulers, beginning with Sultan Ibrahim of Johor in October 1945. The Sultan quickly consented to MacMichael's proposal scheme, which was motivated by his strong desire to visit England at the end of the year. MacMichael paid further visits to other Malay rulers over the proposal, and sought their consent over the proposal scheme. Many Malay rulers expressed strong reluctance in signing the treaties with MacMichael, partly because they feared losing their royal status and the prospect of their states falling into Thai political influence.[25]

The full impact of the proposal came into view on 22 January 1946 with publication of the British government's white paper on the Malayan Union and the impacts of the treaties the sultans had been persuaded to sign. The Colonial office suddenly found that it had forgotten its own pre-war advice on the need to maintain the Malay populations position of privilege.[26] Malay reaction was swift with seven political dissidents led by Awang bin Hassan organised a rally on 1 February 1946 to protest against the Sultan of Johore's decision to sign the treaties, and Onn Jaafar, who was then serving as a district officer in Batu Pahat, was invited to attend the rally.[27]

A Pan Malay Congress was held on 1 March 1946 (the first of several) which began UMNO. The organisations aim was to oppose the Malayan Union. Onn also managed to persuade the sultans to boycott the inauguration ceremony for the Malayan Union. The British capitulated and agreed that while the Malayan Union still commenced on 1 April 1946 negotiations began in July 1946 for its replacement.[28][24]

Gallery

[edit]

See also

[edit]- British Malaya

- British Military Administration (Borneo)

- Japanese occupation of British Borneo

- Japanese occupation of Malaya

- Singapore in the Straits Settlements

References

[edit]- ^ F. S. V. Dommison, British Military Administration in the far East (London, 1956)

- ^ Post War Colonial Policy, 50 Years of Malaysia: Federalism Revisited, Dr Andrew J Harding, Dr James Chin, Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd, 2014, ISBN 9814561967, 9789814561969

- ^ Military Government and its Discontents: The Significance of the British Military Administration in the History of Singapore and Malaya, Kelvin Ng, Research and Practice in Humanities & Social Studies Education, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

- ^ Cooper, B. (1998). The Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA). In B. Cooper, Decade of Change: Malaya and the Straits Settlements 1936–1945 (pp. 426–464). Singapore: Graham Brash.

- ^ a b Financing Japan's World War II Occupation of Southeast Asia, Gregg Huff and Shinobu Majima, Pembroke College - University of Oxford and Faculty of Economics - Gakushuin University, pp. 7–19

- ^ a b Malaya before the war, The Japanese Occupation of Malaya: A Social and Economic History, Paul H Kratoska, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1998 ISBN 1850652848, 9781850652847

- ^ Currency replacement and price freeze, Syonan Shimbun, 23 February 1942, Page 3

- ^ 300 Tons of 'Banana' notes in Kuala Lumpar, The Straits Times, 10 October 1945, p. 3

- ^ "WW II Allied Propaganda Banknotes". www.psywarrior.com. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ a b British Military Administration - Malaya, The Straits Times, 7 September 1945, Page 1

- ^ a b British Document On the End of Empire Vol.1, edited by S. R. Ashton. London: University of London Press, 1995.

- ^ Banana Money, The Straits Times, 8 September 1945, page 1

- ^ Moratorium in Malaya, The Straits Times, 8 September 1945, page 1

- ^ Hone, H. R. (1946). Report on the British Military Administration of Malaya: September 1945 to March 1946 (p. 5). Kuala Lumpur: Malayan Union Government Press. Call no.: RCLOS 959.506 HON

- ^ a b c d e f g Stubbs, Richard. Heart and Minds in Guerrilla Warfare: The Malayan Emergency 1948-1960. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- ^ Martin Rudner, 'The Organisation of the British Military Administration in Malaya', Journal of Southeast Asian History 9 (March 1968), p.103.

- ^ Khong Kim Hoong, Merdeka! British Rule and the Struggle for Independence in Malaya, 1945-1957 (Petaling Jaya, Malaysia: Institute for Social Analysis, 1984), pp. 42-43

- ^ Occupation spreads to Johore, The Straits Times, 8 September 1945, page 1

- ^ The new dollar, The Straits Times, 10 September 1945, page 1

- ^ Malaysia, a Racialized Nation: Study of the Concept of Race in Malaysia, Rie Nakamura1, School of International Studies Universiti Utara Malaysia, 2012

- ^ Donnison, British Military Administration, p.158.

- ^ Telegram to all Colonies, etc. From the Secretary of State, Colonies,5 September 1947, CO537/2974.

- ^ Carnell, Malayan Citizenship Legislation, International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 1952

- ^ a b The British Empire and the Second World War, Ashley Jackson, Humbledon Continuum, 2006, page 437

- ^ Bayly, Harper, Forgotten wars: Freedom and Revolution in Southeast Asia, pg 133-4

- ^ Nationalism in Malaya, John Bastin and Robin W Winter, Oxford University Press, 1966, pages 347-358

- ^ Bayly, Harper, Forgotten wars: Freedom and Revolution in Southeast Asia, pg 211

- ^ From Malay Union to Federal Constitution, Virginia Matheson Hooker, A short history of Malaysia - linking east and west, Allen and Unwin, 2003, pages 186-188, ISBN 1 86448 955 3

- F. S. V. Donnison, "British Military Administration in the far East." Pacific Affairs 30, no. 4 (1957) : 389–392.

- Stubbs, Richard. Heart and Minds in Guerrilla Warfare: The Malayan Emergency 1948-1960. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 981-210-352-X

- Rudner, Martin. "The Organization of the British Military Administration in Malaya" ,Journal of Southeast Asian History 9, no. 1 (1968): 95–106.

- British Document On the End of Empire Vol. 1, Edited by S. R. Ashton. London: University of London Press, 1995. ISBN 0 11 290540 4

KSF

KSF