British Symphony Orchestra

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 39 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 39 min

The British Symphony Orchestra (BSO or BrSO) is the name of a number of symphony orchestras, active in both concert halls and recording studios, which have existed at various times in Britain since c1905 until the present day.[a]

There were gaps of several years when the orchestra's name disappeared from the public view (see § Historical overview). The various orchestras were only active for about fifteen years between 1905 and 1939.

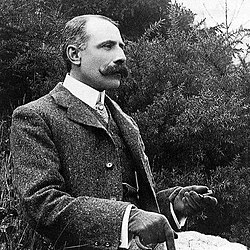

The conductors of the orchestra's first incarnation from 1905 included William Sewell, Julian Clifford senior and Hamilton Harty. After World War I Raymond Rôze reformed the orchestra as a properly-constituted, full-time body of musicians. Rôze died unexpectedly in 1920 and was succeeded as chief conductor by Adrian Boult, who gave numerous public concerts over several years. Other musicians conducting the orchestras at the time included Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Franco Leoni, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Edward Elgar. Members of the orchestra during this period included Albert Sammons and § Frederick Holding as leaders, and Eugene Cruft on bass.

In the early 1930s the name 'British Symphony Orchestra' appeared on the label of many recordings by the Columbia Graphophone Company as a cover name or pseudonym for the orchestra of the Royal Philharmonic Society. Conductors during this period include Ethel Smyth, Oskar Fried, Bruno Walter, Felix Weingartner, and Henry Wood. A few public concerts were given in London with an orchestra of this name during the years leading up to the Second World War.

More recently, the music for the 1989 film La Révolution française was composed and conducted by Georges Delerue, and played by the British Symphony Orchestra. Since 2016 an orchestra of the same name founded by Philip Mackenzie has made a number of concert appearances in Britain, and also toured in China.

Historical overview

[edit]The history of the various British Symphony Orchestras seems to fall into five approximate periods.

- 1905–1910: Formed by the organist, conductor, and composer William Sewell in around 1905, and active in London concert halls for about five years until c1910. There seem to be no extant recordings.

- 1919–1923: Formed in summer 1919 by Raymond Rôze for professional musicians who served in the Army during WW1. He made their first recording in around 1919. Rôze died aged about 45 in March 1920. The orchestra continued to give concerts in London mainly under Adrian Boult, who also made his first recordings with this ensemble. They seem to have given few public concerts after about 1923.

- 1930–1932: Recording orchestra. From 1930 to 1932, the name in general only appears on record labels, albeit with a number of well-known conductors such as Felix Weingartner, Bruno Walter and soloists like Joseph Szigeti. The orchestral musicians involved may have had more permanent jobs with other orchestras, and the name 'British Symphony Orchestra' may have been used to avoid contractual obligations.

- 1934–1939: A few public concerts in 1934–5 and 1939 were given with a British Symphony Orchestra. There seem to be no recordings from this period.

- Recent formations:

- 1989: The music for the 1989 film La Révolution française, composed and conducted by Georges Delerue, was played by the British Symphony Orchestra, an ensemble of freelance musicians assembled for just this task.

- 2004: A British Symphony Orchestra played at an extravagant wedding in India for two sons of Subrata Roy.

- 2016: Formed by Philip Mackenzie with freelance musicians. It has performed as a backing orchestra for Never the Bride, and with ABBA and Elton John tribute bands. The orchestra made a classical concert tour in China in 2017–18.

For orchestras with a similar name or initials, see also § Disambiguation

First formation: 1905 – c. 1910

[edit]

In October 1905 William Sewell,[1][2][4][5] organist at the Birmingham Oratory, director of the Midland Gleemen[6] and later sub-organist of Westminster Cathedral, placed an advertisement in The Musical Times:

- "The British Symphony Orchestra (conductor, Mr. W. Sewell) is a new combination of orchestral players which seeks for public favour."[7]

One of the newly-formed British Symphony Orchestra's first concerts took place at the Æolian Hall, London, on 7 December 1905. The Irish violinist Rohan Clensy[b] who had studied with Eugène Ysaÿe, played Max Bruch's Violin Concerto No. 2. The Standard's critic thought that Clensy was "a clever and thoughtful artist, whose playing shows intelligence and taste. His performance [...] was, on the whole, artistic. The phrasing was clear, and the execution facile, but there was sometimes need of more life and passion, and the tone was somewhat cold. The orchestra gave him good support, and their playing of Schubert's overture. Alfonso und Estrella, an attractive work, which is not often heard, was virile and effective." The programme also included Bach's Suite No. 3 in D and Grieg's Norwegian Dances.[9]

On 18 December 1905 Sewell conducted the BSO with Maria Sequel[11] in Mendelssohn's G minor piano concerto. The music critic of The Standard noted that in the orchestra's playing "there were some rough places, however, which doubtless will become smooth with more practice and experience in their performance of the Figaro and Hebrides overtures."[12]

Again at Aeolian Hall, on February 16, 1906, Lucia Fydell[c] and Atherton Smith[d] with the British Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sewell, gave a recital consisting chiefly of excerpts from Saint-Saëns's Samson and Delilah. "Miss Fydell has a powerful voice and dramatic perception, but she would be heard to greater advantage on the stage than in the concert-room."[14]

The agents for the British Symphony Orchestra in March 1906 were Concert-Direction Limited,[15] originally founded in August 1905 with Louis and Laurence Cowen as directors. It changed its name in July 1906 to Vert and Sinkins Concert-Direction Limited in 1906. Fernando Vert was the brother of Narciso Vert, whose musical agency later became known as Ibbs and Tillett.[16]

Hamilton Harty who, like William Sewell, had been a church organist (in County Down) conducted what seems to be his first London orchestral concert on 5 April 1906, with the British Symphony Orchestra at the Queen's Hall.[17] Winifred Christie played César Franck's Symphonic Variations and Saint-Saëns' Piano Concerto No. 2.

On 7 April fr:Louis Abbiate played Widor's 'cello concerto and Adrien-François Servais' Concerto Militaire (works of "small musical value today"), with Julian Clifford senior, who "conducted with conspicuous skill".[18]

Two more concerts followed, one at the Queen's Hall on 21 April, and on 24 May 1906 at the Aeolian Hall.[19]

National Sunday League concerts

[edit]The orchestra appeared at a number of concerts organised by the National Sunday League, which was opposed to sabbatarianism, and promoted rational recreation on Sundays.[20][21]

The light soprano Isabel Jay appeared with the BSO at the Alhambra Theatre of Variety on 7 April 1906.[22][e] Harty conducted again on 21 October 1906 at the Queen's Hall, with Edith Kirkwood and Gertrude Lonsdale singing.[f]

On 30 November 1907 the British Symphony Orchestra appeared at The Crystal Palace in a concert including Harty's own Ode to a Nightingale sung by Agnes Nicholls (his wife), and Julius Tausch's Concerto (actually March and Polonaise) for six timpani: the soloist was Gabriel Cleather, "who became a very busy man during the performance".[24]

Amalgamated Musicians' Union concerts

[edit]

According to John Lucas, the British Symphony Orchestra was "formed in 1908 by the Amalgamated Musicians' Union to provide work for its members on Sundays."[25] Albert Sammons, the leader, also played in the restaurant band at the Waldorf Hotel, where Thomas Beecham recruited the 23 year-old for his new Beecham Symphony Orchestra.[25]

The second concert on 4 October was reviewed in The Standard:

- "The second of a series of concerts organised by Mr. Oswald Stoll and the Amalgamated Musicians' Union—the profits of which are given to the benevolent funds of this society—was given last evening at the London Coliseum.[g] The programme was furnished by the British Symphony Orchestra, consisting of l00 instrumentalists, the vocalists being Miss Perceval Allen and Mr. Lloyd Chandos,[h] the conductors Messrs. J. M. Glover and J. Skuse.[i] An exceptionally large audience was present."[27]

On 18 October the vocalists were Kitty Gordon, William Green and Maria Yelland, 'The Cornish Contralto'. The conductors were Joseph Skuse and Leonard Chalk.[j][29]

Two more Musicians' Union Sunday evening concerts took place on 4 and 18 April 1909 at the Coliseum. The British Symphony Orchestra, led by Albert Sammons, was conducted by Alick Maclean and Joseph Skuse.[30]

"The great success of the Sunday evening concerts initiated by the Amalgamated Musicians' Union at the Coliseum two years ago has induced the union to undertake a similar series of concerts at Queen's Hall. Beginning on 4 September 1910, Mr. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor will conduct his Hiawatha's Wedding Feast with the British Symphony Orchestra and Choir. During the season, which extends to June, 1911, many interesting and novel works are to be produced by the orchestra and choir, [...] and some of the best conductors will share the responsibility of directing the different works."[31]

According to Lucas, Beecham conducted two Musicians' Union concerts with the British Symphony Orchestra in 1910.[32] One took place on Sunday 3 April 1910, with the contralto Carmen Hill.[33][34]

On 18 September 1910 at Queens Hall, Franco Leoni's dramatic cantata, The Gate of Life conducted by the composer, was performed by Mme. Ada Davies,[35] Giuseppe Lenghi-Cellini,[36] and Wilfrid Douthitt[37] with the British Symphony Orchestra and Choir.[38]

Second formation: 1919–1923

[edit]Background

[edit]

After the end of WW1 a second British Symphony Orchestra was formed in 1919 by the theatre composer and conductor Raymond Rôze. The personnel were all de-mobbed soldiers, many of whom had served abroad in the Army, and who had all been professional musicians before the war, some of them established soloists.[39]

This was not his first experience with military affairs: just a few weeks before the war broke out in 1914, Rôze had organised the London Arts Corps (or sometimes United Arts Force) (later the 1st Battalion, County of London Volunteer Regiment (United Arts Rifles). This was a civilian volunteer Home Defence battalion consisting entirely of musicians, writers and artists who for various reasons did not wish to join the regular or Territorial Army.[40][41] The roll-call of those involved reads like a Who's Who of the artistic, musical and literary world, headed up by Sir Arthur Pinero as chairman, Lord Desborough, Gerald du Maurier, Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree and many others. There was a distinguished list of naval and military patrons,[42] such as Major-General Sir Alfred Turner, and possibly including some of the later patrons of the British Symphony Orchestra.[39][k]

Rôze also supplied the battalion with several hundred modern .303 Martini–Enfield carbines and 10,000 rounds of ammunition purchased on his own responsibility, to replace the practice weapons (described as "neolithic flintlocks") normally issued by the War Department.[46][41] The corps gradually became an official Army volunteer battalion, and Rôze resigned as Hon. Secretary in January 1915.[46]

During the war, the promising young baritone Charles Mott (who had sung in Rôze's opera Joan of Arc) was called up c1917, joined the Artists' Rifles (a different battalion) and was killed in 1918 at the Third Battle of the Aisne.[l]

1919

[edit]At the time of its founding in summer 1919, it was the only permanent London orchestra apart from the London Symphony Orchestra,[47] which was founded in 1904 by disgruntled players from the Queen's Hall orchestra.

The orchestra under Rôze gave a Royal Command Performance at Buckingham Palace for George V and Queen Mary. The concert included Reels and Strathspeys for strings and wind by Joseph Holbrooke[48] and Rôze's overture to his incidental music for Julius Caesar.[citation needed]

Rôze conducted the orchestra's first public concert at the Royal Albert Hall on 21 September. The London critic of The Musical Times remarked on the familiar faces on the platform:

- "The words 'first appearance,' however, read oddly in connection with a band largely made up of players whose names are well known to London audiences, some of them soloists. The 'British Symphony Orchestra' begins by claiming attention on the ground that all its members have served in the Army, mostly abroad, but it should soon take a prominent position on its musical merits. Mr. Raymond Rose [sic] conducted, and Mr. Tom Burke sang.[39]

The orchestra, again conducted by Rôze, gave a programme in the Albert Hall, Nottingham on 4 December 1919, "embracing Rossini's ever-green William Tell overture, Grieg's Peer Gynt Suite, and the third movement of Tchaikovsky's 'Pathétique' symphony." Katharine Goodson (piano), Watkin Mills (baritone), and Bronisław Huberman (violin), were "cordially appreciated. M. Paul Frenkel[m] acted as accompanist."[49]

Another concert took place on 12 December 1919, with Tchaikovsky's sixth symphony, two Passacaglias by Cyril Scott who also conducted, plus Scott's Idyllic Phantasy for voice, oboe and cello, (performed by Astra Desmond, Arthur Foreman[n] and Cedric Sharpe respectively).[o] "[The orchestra] has been heard by the King and Queen; it has a very strong list of naval and military patrons; and is a first-class orchestra, the tone of the strings being particularly full and rich, and the wood-wind conspicuously mellow."[42]

On 27 December 1919, the BSO appeared at the Royal Albert Hall with Albert Coates conducting a piano concerto with Leopold Godowsky, and the tenor Clarence Whitehill accompanied by Harold Craxton.[51]

1920

[edit]Raymond Rôze was too ill to conduct a BSO concert on 10 February 1920, and Frank Bridge stepped in. Albert Sammons played Rôze's Poem of Victory for violin, and Joseph Holbrooke conducted his own early work, The Viking.[p]

However, the series of concerts of the British Symphony Orchestra had to be abandoned owing to lack of support. Rôze's final concert with the orchestra took place at the Queen's Hall on 23 February 1920. The players "gave an excellent performance of Hubert Bath's symphonic poem The Vision of Hannele [1913], perhaps the best of his more ambitious works."[52] The concert also included Two Dances by Dorothy Howell.[q]

Rôze, the orchestra's founder, died suddenly on 30 March 1920 aged around 45, and Adrian Boult, as his "fortunate successor", became chief conductor.[47][53]

Quinlan Symphony Concerts

[edit]

The impresario Thomas Quinlan organised a series of twelve "super-concerts" at Kingsway Hall from October 1920 to January 1921, featuring various orchestras, including the Quinlan Orchestra, and the British Symphony Orchestra conducted by Boult, Saturday afternoons at 2.45.[54][55][56][57] According to Boult, this was possibly the first time orchestral music had been heard in the hall, originally built in 1912 as a Methodist place of worship.[47]

The first concert included Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 3; Vladimir Rosing ("...'the blind Russian tenor', as somebody in the hall called him – a description which all who have seen him sing will understand") sang Tchaikovsky's 'Lensky's Farewell' and other things "in his usual intense manner", and Madame Renée Clement played Édouard Lalo's Violin Concerto No. 1 in F. The concert closed with Tchaikovsky's 5th Symphony.[r]

The second of the Quinlan Concerts in October/November included the tenor Joseph Hislop and the violinist Jacques Thibaud. The programme contained notes by Edwin Evans.[58]

Arnold Bax's tone-poem The Garden of Fand received its British première on 11 December.[s] Guilhermina Suggia also played Saint-Saëns's Cello Concerto No. 1.[60] The London music critic of The Musical Times, Alfred Kalisch, was disapproving of Suggia's somewhat demonstrative style of playing.[t]

1921

[edit]Moriz Rosenthal played the Chopin Piano Concerto in E minor with the BSO at the Kingsway Hall on Saturday, 15 January 1921.[61] The concert included Vaughan Williams's London Symphony, and Miriam Licette sang.[u]

As part of the Oxford Subscription Concerts, the BSO conducted by Boult gave an orchestral concert on 20 January 1921.[62] At a concert of the British Symphony Orchestra on 5 February, Boult revived John Ireland's The Forgotten Rite.[63]

The Quinlan Concerts at the Kingsway Hall came to an end in March 1921 when their promoter was declared bankrupt.[47][v]

Bach's St Matthew Passion was performed in Westminster Abbey by the Westminster Abbey Special Choir, with the British Symphony Orchestra, on Monday, March 14, 1921.[64]

The British Musical Society, founded in 1917, gave two concerts in June at the Queen's Hall with the British Symphony Orchestra. At the first, Sir Eugene Goossens and Boult conducted an all-British concert on 14 June 1921: Joseph Holbrooke – Overture to The Children; Ralph Vaughan Williams – The Lark Ascending; Sir Eugene Goossens – symphonic poem The Eternal Rhythm;[65] Cyril Scott – Piano Concerto (the composer at the pianoforte); and Gustav Holst's The Planets.[66] This concert included the first performance of the orchestral version of The Lark Ascending, played by Marie Hall who owned a Viotti Stradivarius.[67][68]

At the second "Orchestral Plebiscite Concert" on 16 June, Hamilton Harty conducted Elgar's Enigma Variations and Bantock's The Sea Reivers: and Walter Damrosch took the podium for performances of the 'Dirge' from Edward MacDowell's Indian Pieces, Adventures in a Perambulator by John Alden Carpenter and three numbers from Damrosch's own Iphigenia in Aulis.[69]

The Russian tenor recitalist Vladimir Rosing presented a week of small-scale opera at the Aeolian Hall from 25 June to 2 July 1921, with stage director Theodore Komisarjevsky. This brief season of Opéra Intime included The Queen of Spades, The Barber of Seville, Bastien und Bastienne, and Pagliacci.[70] The stage of the Aeolian Hall was very small, and looked "overcrowded with more than six people on it."[71] Apart from Rosing, other singers in the Tchaikovsky were Augustus Milner,[w] Moses Mirsky,[x] and Raymond Ellis.[y] Winifred Lea, Tudor Davies and Mostyn Thomas appeared in Mozart's comedy, and Raymond Ellis sang Silvio in Pagliacci.[71] The orchestra consisted of principals of the British Symphony Orchestra, with an organ and piano and "did its work very effectively under Mr. Adrian C. Boult." The scores were reduced for the purpose by Leslie Heward.[71] The Opéra Intime company then toured Glasgow and Edinburgh.

People's Palace concerts

[edit]The People's Palace (now part of Queen Mary College) on Mile End Road, London, was opened by Queen Victoria on 14 May 1887. It included the Queen's Hall for concerts, a vaulted reading room and a Polytechnic college.[74] It was destroyed by fire in 1931.

The British Symphony Orchestra under Boult gave two seasons of orchestral concerts in 1921 and 1922.[53][75] Use of the hall was given rent-free by William Ellison-Macartney, Governor of the People's Palace. Boult remembers meeting him at the pavilion at Lord's Cricket Ground, where he was also a governor.[76] The swimming-pool at the People's Palace was much appreciated by Boult and members of the orchestra after concerts.[76][77]

The first concert took place on 16 October 1921. Boult conducted Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G for strings (Bach), A Shropshire Lad by George Butterworth, Brahms's Symphony No. 2, and Francesca da Rimini by Tchaikovsky.[78] Boult preceded each piece with a short, non-technical spoken introduction from the podium. Although these were well-received, Boult realised that "many of the audience were from the West End, so knew as much as I did about the music. This cured me of the desire to talk to my audiences."[76][z]

A second People's Palace concert followed on 30 October. Mendelssohn's Hebrides Overture; Beethoven's 5th Symphony, Domenico Scarlatti arr. Tommasini – The Good-Humoured Ladies,[80] and Armstrong Gibbs's incidental music for Maurice Maeterlinck's The Betrothal. It was reviewed by The Times the following day:

- "A storm of applause ... Mr Holding leads a body of efficient and ardent musicians. They must have felt they were playing to enthusiasts, and there is no performer in that case who does not surpass himself. An audience seldom knows how much all that is worth having in music lies in its own hands."[79]

On 13 November the overture was Beethoven's Egmont Overture, Frederick Holding gave Elgar's Violin Concerto, and the symphony was Mozart's No. 39 in E♭.[81]

Other works included in the programmes of the six concerts before Christmas: Schubert: C major symphony, and one by Haydn; Elgar: 2nd symphony ("with which Mr. Boult made such a stir at Queen's Hall last year"), and the Violin Concerto; Holst: Beni Mora Suite; Richard Strauss: Don Quixote; Bliss's Mêlée Fantastique; Frederick Laurence: Dance of the Witch Girl;[82] overtures to Weber's Der Freischütz and ]Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg overtures, and others.[53]

Eugene Cruft, the principal double-bass, was the orchestra's secretary in 1921.[53]

1922

[edit]

The first People's Palace concert of the new year took place on 15 January 1922. Works played included Mozart's Don Giovanni overture; Beethoven's 4th Symphony; George Butterworth's first published work, Two English Idylls (1910–11); and Wagner's Siegfried Idyll.[aa]

On January 22 the Bach Choir, under its chief conductor Ralph Vaughan Williams, joined the British Symphony Orchestra and gave three of Bach's Church cantatas: Bide with Us, Jesus took unto Him the Twelve, and The Sages of Sheba. César Franck's Symphony in D minor and John Ireland's The Forgotten Rite were played by the orchestra under Boult on February 12. The concerts were now taking place weekly.[83]

The BSO conducted by Boult gave an orchestral concert on 2 February 1922 as part of the Oxford Subscription Concerts, including Butterworth's A Shropshire Lad and Elgar's Symphony No. 2.[84][ab]

Nevertheless, attendance figures at the People's Palace concerts had fallen sharply, and after a concert on 5 March 1922 which included Vaughan Williams's London Symphony, they were disbanded.[ac]

At the Queen's Hall on 7 April 1922, Vaughan Williams again conducted the Bach Choir with The Northern Singers (Chrissie MacDiarmid, Florence Taylor, John Adams and George Parker) with the British Symphony Orchestra, led by Frederick Holding. Included in the programme were: William Byrd: Christ is Risen Again; Charles Burke: St Patrick's Prayer, Fantasia for chorus and orchestra on two Irish Hymn Melodies;[ad] Holst's Choral Hymns from the Rig Veda; and the Stabat Mater by Dvořák.[85][86]

1923

[edit]

Boult seems to have made his last records with the orchestra in February 1923. (See also British Symphony Orchestra discography). The BSO's last concert appearance seems to have been with Elgar in Aberystwyth in 1923.

A poster for the 4th Aberystwyth Festival advertised the special visit of Sir Edward Elgar and the British Symphony Orchestra, London, 22, 23 and 25 June 1923.[87]

An advance notice in The Musical Times gives the details:

- "The fourth Aberystwyth Festival will be held by the University College of Wales at the University Hall, Aberystwyth, on June 22 to 25. The conductors will be Sir Edward Elgar, Sir Walford Davies [Professor of Music at Aberystwyth], and Dr. Adrian C. Boult. The choir and orchestra will be formed of members of the College Choral and Orchestral Unions, with various other contingents, and the British Symphony Orchestra. The following is the programme: June 22, Mozart's Symphony in E flat and works by Elgar; June 23, Beethoven's seventh Symphony and Choral Fantasia; June 24, public rehearsal of the St. Matthew Passion; June 25, the St. Matthew Passion (afternoon) and miscellaneous programme (evening)."[88]

- Elgar and Jerusalem

According to Sir Jack Westrup in a letter to The Musical Times (October 1969), Elgar's orchestration of Parry's Jerusalem was originally made for the Leeds Festival in 1922 when the first half of one of the concerts was devoted entirely to Parry's music, conducted by Sir Hugh Allen. Allen used it again in Oxford in a performance by the Oxford Bach Choir. Westrup had not heard of any performance since then. When Allen died in 1946, Westrup found the autograph of Elgar's arrangement. On the cover is written, in his own hand: 'To Hugh P. Allen in dear memory of Hubert Parry, September 1922'. When Parry's copyright expired at the end of 1968, it occurred to Westrup that Elgar's orchestration, "which is clearly designed for mass singing", should be better known, and it was published by Curwen Press.[89]

Ian Parrott replied two months later: "Professor Sir Jack Westrup in his letter [...] says that he knows of only one performance of Elgar's orchestration of Parry's Jerusalem after the Leeds Festival of 1922. My colleague, Charles Clements,[90] reminded me that it was used on the occasion of Elgar's visit to the Aberystwyth Festival of 1923. On that occasion Walford Davies and Mr Clements played as a piano duet in the front of the orchestra and he felt that Elgar did not wholly approve, especially as Sir Walford insisted on having the lid open. However, since it is for 'mass singing', no doubt Elgar fell in with Sir Walford's typical ad hoc treatment."[91]

Orchestra members

[edit]- Albert Sammons – leader in 1909

- Frederick Holding – leader in 1921

- Eugene Cruft – principal double bass from 1919.[79]

- James MacDonagh – principal oboe / cor anglais

- Frederick Holding

A pupil of Carl Flesch, Holding owned a Stradivarius ('The Penny').[92]

He was leader of the 'old' Philharmonic Quartet, formed in 1915 initially consisting of Arthur Beckwith (first violinist), (Sir) Eugene Aynsley Goossens (second violin), Raymond Jeremy (viola) and Cedric Sharpe (cellist). World War 1 interrupted their work as some of the members were eventually called up for service. In 1918 they reformed with Frederick Holding taking over from Goossens, becoming the first violin in 1919 with Thomas Peatfield the new second violinist. For a series of concerts in February 1921 at the Essex Hall the quartet consisted on 2 February of: Holding (1st violin), Samuel Kutcher (2nd violin), E. Tomlinson (viola) and Giovanni Barbirolli (cello). For the second concert on 13 February 1921 it consisted of Frederick Holding, Samuel Kutcher, Raymond Jeremy and Cedric Sharpe.[93]

- Eugene Cruft

During WW1, Eugene Cruft helped recruit musicians to entertain the troops, while serving with the Motor Transport division of the Army Service Corps. He fought with the 2nd Battalion of the Rifle Brigade at Passchendale and on the Somme. He helped to form the new British Symphony Orchestra.[94] He was the orchestra's Honorary Secretary from its inception, and became a life-long friend of Boult.[47] He was principal double-bass player in the BBC Symphony Orchestra 1929–1947 during Boult's conductorship.

- James MacDonagh

James MacDonagh (1881–1931), an accomplished musician on several instruments, was principal oboist and cor anglais player with the British Symphony Orchestra. He was the third eldest brother of Thomas MacDonagh, who was shot in Kilmainham Gaol with Padraic Pearse and Tom Clarke after the 1916 Easter Rising. His son, Terence MacDonagh (1907/08–86), also played the oboe and cor anglais with both the BBC Symphony Orchestra (of which he was a founder member), and with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under Sir Thomas Beecham; he served on the board of the Royal College of Music.[95]

Third formation: recording orchestra, 1930–1932

[edit]

After the 4th Aberystwyth Festival in summer 1923, the orchestra's name seems to disappear entirely until the 1930s when it appears on around fifteen or so 78 rpm recordings made by the Columbia Graphophone Company in Central Hall, Westminster from 1930 to 1932.[ae] According to Michael Gray,[96] at least three of these electrical recordings were very probably made by the Orchestra of the Royal Philharmonic Society, and it seems possible that this pickup orchestra is responsible for the remainder, as well as recordings of Sibelius's first two symphonies with Robert Kajanus.

A certain amount of mystique surrounds these vintage recordings made around 90 years ago: partly because the identity of this ensemble is somewhat uncertain; partly because in only a handful of recordings do the details taken from Columbia's own contemporary session logs and matrix notes actually match up completely with the information on the record labels; and partly because of Columbia's habit of replacing old recordings with newer ones (often of different works and by other artists), but keeping the old catalogue number.

Conductors of these recording sessions include Ethel Smyth, Oskar Fried, Bruno Walter, Felix Weingartner, and Henry Wood.

Fourth formation: public concerts, 1934–1939

[edit]In October 1934 a somewhat subdued notice appeared in the organ advertisement section of The Musical Times:

- The London Society of Organists, South-Western Branch [ie London SW]. "The British Symphony Orchestra (recruited from unemployed British Musicians) will supply small combinations for Oratorios, Cantatas, and any Church functions needing musicians."[97]

From January 1934 to January 1935 a British Symphony Orchestra appeared in three National Sunday League Concerts at the London Palladium, all conducted by Charles Hambourg.[98][af] 7 January 1934: orchestral concert. 4 November 1934: the violin soloist was Marie Hall, who had given the first performance of The Lark Ascending with an earlier British Symphony Orchestra in June 1921. On 13 January 1935 the concert included the duo-piano team of Vronsky & Babin.[100]

The English composer and conductor Charles Proctor gave two concerts on 12 November 1938 and 29 April 1939, conducting his own Alexandra Choral Society with a British Symphony Orchestra at the Northern Polytechnic Institute, Holloway Road.[101][102]

Recent formations

[edit]1989

[edit]The music for the 1989 film La Révolution française, directed by Robert Enrico and Richard T. Heffron, was composed and conducted by Georges Delerue. It was performed by the British Symphony Orchestra with chorus.[103] This seems to have been an ensemble of freelance musicians from the Greater London area, recorded at HMV Abbey Road Studios in August 1989.[104]

2004

[edit]At the sumptuous wedding of Sushanto and Seemanto Roy, the sons of the Indian businessman Subrata Roy, chairman of Sahara India Pariwar, a British Symphony Orchestra was specially flown to Lucknow to perform modern and traditional Indian melodies.[105]

2016

[edit]Philip Mackenzie, as principal conductor, formed a British Symphony Orchestra in 2016. The orchestra is made up of freelance musicians and based in London. It has performed with, inter alia, the Revival ABBA Tribute Band, Never the Bride and Gordon Hendricks.[106][107]

George Morton was the guest conductor of the British Symphony Orchestra's tour in China (27 December 2017 – 9 January 2018).[108] They played nine concerts including works by contemporary Chinese composers, along with Western music including Sibelius: Finlandia; Tchaikovsky: Marche Slave; Bizet: Carmen Suite No. 1; and Elgar: Enigma Variations.[109][110]

Discography

[edit]In popular culture

[edit]- In Diana Wynne Jones's 1984 novel for young adults Fire and Hemlock, Thomas Lynn (Tam Lin) was a member of a 'British Symphony Orchestra' and there is reference to a poster or photo of other musicians in the band, with some of whom Tom wants to form a quartet.[111][ag]

- A 'British Symphony Orchestra' appears in The Lady in the Van, a 2015 film directed by Nicholas Hytner, written by Alan Bennett, and starring Maggie Smith as 'Miss Shepherd' and Alex Jennings as Alan Bennet. It tells the (mostly) true story of 'Mary Shepherd', an elderly woman who lived in various dilapidated vans on Bennett's driveway in London for 15 years. Miss Shepherd was a musician. In one scene when the character of Alan Bennett is sifting through Mary Shepherd's paperwork, he finds a poster for a concert at the King's Hall in which she played Chopin's Piano concerto No. 1 with the British Symphony Orchestra.[ah] The BSO is played in the film by the BBC Concert Orchestra, conducted by George Fenton, who also composed the incidental music.[116]

Disambiguation

[edit]For other orchestras with the same initials, see BSO § Music.

- Not to be confused with the British Women's Symphony Orchestra[117] or the British Youth Symphony Orchestra.[118][ai]

- A general quiz website includes a reference to a certain "Karl Mack (german conductor of the British Symphony Orchestra), arrested for not playing the star spangled banner."[sic][aj] A web page including a biography of the composer Carlos Guastavino mentions 'the British Symphony Orchestra', probably meaning the BBC Symphony Orchestra.[119]

- Various films and 78rpm recordings featured ensembles with a similar-sounding title, with misleading results for those unable to read. For example, the band for Alfred Hitchcock's 1929 Blackmail—produced by British International Pictures—was the 'British International Symphony Orchestra'[120] and not, according to at least one source, the 'British Symphony Orchestra'.[121]

- A number of catchy 78rpm recordings feature the studio ensemble of the Gaumont-British film production company, conducted by Louis Levy, general Music Director at Gaumont. Although the name is correctly hyphenated on e.g. record labels and in listings in the Radio Times (often on a line break), the dash has been frequently omitted in later transcriptions, perhaps leading to confusion. The names used by this ensemble include, chronologically, 'Gaumont-British Studio Orchestra',[al] 'Gaumont-British Symphony'[am] 'Gaumont British Symphony',[an] and the 'Gaumont-British Symphony Orchestra'.[126]

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ There is currently (2019) no single work dealing with the various incarnations of the orchestra. Much of the original information for this article comes from the pages of The Musical Times, whose archive is currently on JSTOR, with restricted access. The following notes attempt to give a flavour of the more detailed reviews, over and above the plain record of performers and works played.

- ^ A multi-talented artist, actor of both stage and film, violinist, and singer who died in France in February 1919 as a corporal in the Military Police Corps. He is commemorated in the last line of the War Memorial in the Theatre Royal, Haymarket.

He sang in Mozart's Der Schauspieldirektor in 1910, as part of Thomas Beecham's wildly extravagant opera season. This was part of a double bill including G. H. Clutsam's A Summer Night.[8] - ^ Lucia Fydell was the great-granddaughter of John Braham, composer of "The Death of Nelson". She had been completing her studies with Jacques Bouhy in Paris, and reappeared in London at the Aeolian Hall in February 1906.[13]

- ^ Dean-Myatt, William (compiler) (2013). A Scottish vernacular discography, 1888–1960 (PDF). (Online at the National Library of Scotland). Hailsham, Sussex: City of London Phonograph and Gramophone Society. Atherton Smith was a Scottish baritone, b. Glasgow 1874, who made some records for Zonophone and Odeon records c1904.

- ^ Isabel Jay opened in The Girl Behind the Counter on 21 April 1906. The musical farce ran for 141 performances. In 1906 she also appeared in Liza Lehmann's comic opera The Vicar of Wakefield, with a libretto by Laurence Housman.

- ^ The full programme included Mozart: Overture The Magic Flute; Hamish MacCunn: Ballad Overture Dowiedens o' Jarrow; Gounod: Waltz Song (Roméo et Juliette); Hamilton Harty: Symphony in D (Irish); Michele Esposito: Poem (first performance in England); Tchaikovsky: Capriccio Italien; Granville Bantock: Song of the Genie; Frederic Cowen: Four English Dances; Weber: Overture Oberon.[23]

- ^ The Coliseum was built by Stoll in 1904, the largest capacity theatre in London.

- ^ London-born tenor, made a number of records for Odeon. A test pressing of him singing Massenet in c1931 aged around 70 is quite affecting.[26]

- ^ Joseph Skuse, of Cricklewood, sub-conductor of the orchestra at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.

- ^ Chalk composed and conducted the music for a 1905 production of Henry V at the Imperial Theatre,[28] which was pulled down in 1908 to make way for the Central Hall, Westminster where a later 'British Symphony Orchestra' made recordings for the Columbia Graphophone Company in the early 1930s. See also British Symphony Orchestra discography.

- ^ Other members of the committee included Sir Edward Elgar, Sir Hubert Parry, Sir Thomas Brock, Sir Edward Poynter, Sir George Frampton, Cyril Maude, and Dion Boucicault. Also actively involved were painters like Sir John Lavery, Sir George Frampton, Lieut.-Col. Solomon J. Solomon, Sir Frank Short, Bernard Partridge and Arthur Hacker; Derwent Wood, George Lambert and others of the Chelsea Arts Club platoon. Actors: Sir F. R. Benson, Arthur Bourchier, Allen Aynesworth, Godfrey Tearle, Nelson Keys, Huntley Wright and his brother Fred, musicians and singers like Thomas Dunhill, Harry Plunket Greene, Dalhousie Young (1866–1921),[43] the conductor C. H. Allen Gill; poets like Emile Cammaerts; novelists like Arthur Applin,[44] Temple Thurston and Keble Howard et al.[45]

- ^ "'The Grey Watch' (Crichton), HMV 4-2795, sung by Charles Mott". Youtube. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ Frenkel made some recordings with Huberman, including Paganini, Bach and Lalo.

- ^ Rec. of Arthur Foreman playing Schumann Romance No. 1. The other side is by Arthur Brooke, an English oboist who played in another BSO.[50] See also Brooke's Method and Brief bio

- ^ The notice by Alfred Kalisch in The Musical Times says it was for piano rather than cello.

- ^ Kalisch, Alfred (1 March 1920). "London Concerts". The Musical Times. 61 (925): 177. JSTOR 910139.

Mr. Frank Bridge is rapidly assuming an almost official position of the conductor who is sent for in an emergency. A few weeks ago he replaced Sir Henry Wood at a few hours' notice. On February 10 he took the place of Mr. Raymond Rôze, who was unfortunately too ill to conduct the concert of the British Symphony Orchestra.

The novelty of the concert was Mr. Rôze's effective Poem of Victory, for violin, with the solo part beautifully played by Mr. Sammons [who had been leader of the first orchestra in 1910], and Mr. Holbrooke conducted his own early work, The Viking. It is one of his most lucid and picturesque scores, though possibly not the original. Mr. Holbrooke is not easily pleased, he can have no reason to complain either of its performance or its reception by the audience. - ^ Mike, Celia (1 June 1990). "Dorothy Howell". The Musical Times. 131 (1768): 297. doi:10.2307/965927. JSTOR 965927.

I am an honours music student at Aberdeen University, and I'm writing a thesis on the composer Dorothy Howell (1898–1982). There are two works of hers for which I can find no copies of scores, or original manuscripts. The works are as follows: 'Two Dances', which was first performed on February 23rd 1920, at the Queen's Hall, by the British Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Raymond Rôze ...

- ^ "Quinlan Subscription Concerts". The Observer. London. 17 October 1920. p. 7. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

Quinlan Subscription Concerts. The Season Opens. ...I entered the Kingsway yesterday and saw Mr. Quinlan's crowd listening to a Bach Brandenburg Concerto. How that would have pleased old Samuel, by the way! I doubt if he ever heard it. If he could get a few of his organ fugues popularised and help to bring out an edition of the "48", it was as much as he could hope for. It was a good idea to open with the Concerto, because, it showed us what the strings of the British Symphony Orchestra could do. They have solid qualities and, as we later learnt, so have the wood-wind and brass.

The founder of the orchestra did a good deal to lick it into shape before he died, and Mr. Boult will soon do more. The stuff is there, and something good can be made of it. Mr. Quinlan's very flamboyant announcements show that he relies a good deal on the attractive powers of his soloists. Those yesterday were Mr. Rosing ("the blind Russian tenor," as somebody in the hall called him – a description which all who have seen him sing will understand) and Madame Renée Clement. The former sang Tchaikovsky's "Lensky's Farewell" and other things in his usual intense manner, and the latter played Lalo's Violin Concerto in F with all the beautiful tone and the grace and delicacy that it calls for. And both had a big welcome, as they well deserved. The concert closed with more Tchaikovsky, the Fifth symphony. It is rather a new thing to carry on a series of first-rate concerts in this hall, but the experiment seems likely to succeed despite the discomfort of the seats. - ^ "In a short interview with Eamonn Andrews broadcast on Irish radio in 1947, Bax cited this work as his favorite of his own compositions, and it was the last piece of his own music that he heard, as Fand was used to close a concert in Dublin just four days before the composer's death.[59]

- ^ Kalisch, Alfred (1 January 1921). "London Concerts". The Musical Times. 62 (935): 27–28. JSTOR 909157.

We heard Mr. Arnold Bax's Garden of Fand played by the British Symphony Orchestra on December 11, on December 16 his November Woods. Both were new to London. [...] At the third of the concerts of the London Symphony Orchestra, on November 29, the programme contained [...] Eugen d'Albert's Violoncello Concerto, which we could well have spared. If it were a really fine work, the composer's hobby of belching forth abuse upon this country would not matter, but as it is particularly dull, even Madame Suggia's magnificent playing could not redeem it. She is a very great artist, but she sometimes comports herself rather as if she were Karsavina miming the actions of a 'cellist.

While she was playing Saint-Saëns's Concerto at the British Symphony Orchestra concert referred to above, her exuberance of gesture resulted in her dropping her bow at a crucial moment. She would be a still greater artist if she did not do these things. - ^ "Music Notes – Return of a Famous Pianist". Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art. 131 (3404): 74. 22 January 1921.

Last Saturday afternoon at the Quinlan Subscription Concert Mr. Moriz Rosenthal, the master technician of the pianoforte, made his reappearance in London for the first time since before the war. He did not do so to the best possible advantage, thanks to his choice of a work that represented neither the genius of its composer nor the special gifts of its interpreter in an adequate light. [...] The real nature and extent of his extraordinary talent will only re-emerge, however, when he gives us one of his big recital programmes and exhibits the diversity of his style, his intellectual grasp, his poetic sentiment, and occasionally one of those torrential rushes and climactic crashes that deprive the listener of breath. It has often been said that, when he does these things, Mr. Rosenthal has no equal; and that saying, after having heard him again in this dullest of Chopin concertos, we believe to be still true.

The first fifty minutes of the concert were devoted to Dr. Vaughan-Williams's fine London Symphony, an admirable performance.

The customary operatic vocal selections—rather reminding one at these concerts of the Philharmonic habit in the old days—were furnished by Mme. Miriam Licette, a conscientious and much-improved singer. - ^ "Concerts and Recitals". Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art. 131 (3411): 220. 12 March 1921.

When will the most venturesome of British concert-managers learn that the Barnum-like methods of their American confreres do not, in the long run, pay in this country? It was palpable from the outset that the Quinlan super-concerts at the Kingsway Hall were doomed to failure. Not only did the prospectus "protest too much", but the programmes were too mixed to prove attractive to a regular clientele. We pointed out these and other mistakes while there was ample time to correct them; but nothing was done. Now the end of the enterprise has come, and our only feeling about it is one of genuine regret for the British Symphony Orchestra and its able conductor, Mr. Adrian Boult.

- ^ An Irish baritone who sang in the première of Busoni's Arlecchino in Zurich in 1917, where he also gave a recital of Irish music promoted by James Joyce in 1919.[72]

- ^ "The Boy Cantor", made records for Zonophone in 1905 aged about 11, won a scholarship to the Guildhall School of Music in 1919 and became Professor of Singing there.[73]

- ^ Photo at "Raymond Ellis as Papageno in The Magic Flute, September 1924". Europeana Collections. (Website in Maltese). Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "Orchestral Music in East London". The Musical Times. 62 (945): 794. 1 November 1921. JSTOR 908976.

Of all the recent efforts that have been made to 'decentralize' the music of London the boldest is the series of East End Symphony concerts of the British Symphony Orchestra with programmes of 'Queen's Hall' standard. These concerts are held at the People's Palace on Sunday afternoons (at 3.30), with Mr. Adrian C. Boult as conductor. Each programme contains a Symphony and a British work. The dates are October 16 and 30, November 13 and 27, December 11 and 18. The success of the opening concert was very encouraging. The hall was well filled—with room for more—and the audience appeared to take huge delight in the programme. [...] Each number was preceded by a short and unacademic explanation by Mr. Boult—a feature that appeared much appreciated. Probably the news that the concert proved so acceptable (without a song from beginning to end) will have spread and provided a full hall for the concert.

- ^ "London Concerts: Music for the People". The Musical Times. 63 (948): 115. 1 February 1922. JSTOR 910977.

If the performance under notice is a criterion, the music will be played with an efficiency unexcelled anywhere. [...] The audience was numerous and appreciative, not least of the conductor's forewords, illustrated by quotation of the leading musical themes by the band. [...]

But when [Boult] took up the baton, the fancy of neophyte and initiate alike was freed. No truer compliment can be phrased. The sunny formality of Mozart, characteristically displayed in the Don Giovanni Overture, Beethoven's monumental trick of genius by which a simple, almost commonplace sequence of notes is, as in the fourth Symphony, transformed by rhythm into a subject of vital significance—these wonders were unfolded with the sure touch of the artist. Nor were the late George Butterworth's folk-song "English Idylls" or Wagner's essay in tender sentiment, the Siegfried Idyll, treated with less sympathy. Warming one's intellectual consciousness at these sacred fires, bodily consciousness of the frigid conditions prevailing outside—and, to a certain extent, inside, the Hall—was for the time being happily lost. H. F. - ^ Kalisch, Alfred (1 March 1922). "Music in the Provinces – Oxford". The Musical Times. 63 (949): 207. JSTOR 910120.

Oxford. Until Dr. Adrian C. Boult came with his British Symphony Orchestra on February 2, Oxford had not made the acquaintance of Butterworth's A Shropshire Lad, a little masterpiece that stands firm in the reputation it made at Leeds years ago. Elgar's second Symphony was added to the debt which Oxford owes to Dr. Boult. – For three days the Town Hall has been the scene of a 'Grand Divertissement,' by members of the Russian Ballet.

- ^ "London Concerts". The Musical Times. 63 (950): 252. 1 April 1922. JSTOR 910533.

A Set-Back in the Mile End Road. The best that can be said about it is that it did not come a week before, so that at least a sadly singularly beautiful performance of the London Symphony of Ralph Vaughan Williams was saved from the wreck. The premature end of the symphony concerts of the British Symphony Orchestra under Dr. Adrian C. Boult at the People's Palace, Mile End, occurred on March 5.

They were the best Sunday concerts in London, but the hall could be only one-third filled, so the deficit was crushing.

The programmes were of purely orchestral music—not an irresistible lure for people of the locality, who possibly might have been more engaged with a little of the personal and dramatic interest of solo and concerto playing; while people of other localities did not appreciate exactly where Mile End is, or how easy of access.

The set-back is sad, but it may be made good next autumn. Meanwhile there is best performance yet heard of Vaughan Williams's Symphony to the credit of orchestra and conductor. Or at any rate the fresh winds and tides of the music seemed this time to sing a more direct appeal. We were helped to hear the composer's recent Pastoral Symphony by this forerunner, and now the forerunner gives up more secrets in the new work's light. Rare music! C. - ^ Broadwood, Lucy E. (January 1920). "Táim Sínte ar Do Thuama. [I Lie on Your Grave]" (PDF). Journal of the Folk-Song Society. VI, part 3 (23): 175 [pdf 111]. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

"Mr. Burke was one of Mr. Gustav HoIst's musical students at the Morley College for Working Men. He joined Mr. HoIst's composition class when already an old and grey-haired man with a very rudimentary knowledge of the theory of music.

For three years Mr. Burke worked hard at counterpoint during his scanty leisure; selecting Irish traditional airs to arrange and using them with wonderful sincerity and musical perception. In 1912 he finished the Fantasia [...] This extraordinarily lovely work was performed at a Morley College concert in 1912, when its power, beauty and originality startled and profoundly moved an audience which included critical musicians of experience.

Meanwhile the composer continued to work eagerly at orchestration under Mr. HoIst's training. He was writing a set of orchestral variations on an Irish tune when death called him away in February 1917. With him died a musician of rare genius who undoubtedly would have taken his place amongst the very best had the circumstances of his modest life permitted. In the words of Mr. HoIst "If old Charles Burke had been a R.C.M. or R.A.M. student, or an Oxford man, how different things would be! - ^ A search of JSTOR for concert notices returns no results at all from the end of 1923 until a handful of record reviews from 1931 to 1933.

- ^ The late Basil Tschaikov[99] had a thing or two to say about Mr. Hambourg's time-beating: Tschaikov, Basil (2006). "Part 4: The joys of touring". The Music Goes Round and Around. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Wynne Jones' partner was the respected Chaucerian scholar John Burrow. who she met just before going up to Oxford in c1952.[112][113]

- ^ At one point in the screenplay, there is a hint that Miss Shepherd played in a Prom concert. This is reinforced by the shot of the poster, apparently for a concert at the King's Hall. In reality, the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts before the war took place in the Queen's Hall (destroyed in the war), and not in the 'King's Hall'.[114] According to Bennett, "I have allowed myself a little leeway in speculating about Miss Shepeherd's concert career, except that if, as her brother said, she studied with Alfred Cortot she must have been a pianist of some ability."[115] There seems to be little, if any, reference to any such actual event before WW2, and the entire episode would thus appear to be the well-researched figment of Mr. Bennett's fevered (if fecund) imagination.

- ^ Sometimes called the 'British Youth Orchestra'. Conducted by Trevor Harvey 1960–72, and defunct after c1982. In turn, not to be confused with the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain, founded 1948, or with various National Schools Symphony Orchestras.

- ^ "Election of 1912". quizlet.com. Retrieved 6 May 2019. This is apparently a mangling of Karl Muck's National Anthem controversy while he was conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra – possibly a mild original OCR-ism where Muck=Mack and Boston=British.

- ^ Walker, Raymond J (n.d.). "Review of 'The Golden Age of Light Music – British Cinema and Theatre Orchestras' – Volume 2". MusicWeb International. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

As David Ades' interesting notes make mention, the final track of selections from the Courtneidge film "Aunt Sally" is the first recording by Louis Levy with the Gaumont British Symphony Orchestra; pretentiously titled, I suggest, when its film studio players would be freelancers.

[123]

It also documents an uplifting composition by the forgotten American, Harry M. Woods [...] An interesting full page picture in the booklet shows a recording session of the Gaumont British orchestra with Louis Levy standing above them on a temporary wooden stage. - ^ Raymond J. Walker briefly refers to a 'Gaumont British Symphony Orchestra' in his a review of a compilation album[122] including Levy and the 'Gaumont-British Studio Orchestra' playing selections from the 1933 Cicely Courtneidge film Aunt Sally. The original film featured Debroy Somers and his Band in the cabaret spots, with probably Levy's studio ensemble providing the general music. Levy recorded selections from the film a year later with the 'Gaumont-British Studio Orchestra', which later became his 'Gaumont-British Symphony', with or without hyphen. Both the album label and the notes by David Ades omit the hyphen when referring to the 'Gaumont-British Studio Orchestra', and its later incarnation, the 'Gaumont-British Symphony'. Walker expands this to an unhyphenated "Gaumont British Symphony Orchestra" (which did actually exist in 1937): but he also throws some interesting light on the nomenclature of 'The British Symphony Orchestra' and its somewhat impermanent nature. [ak]

- ^ e.g. Mysteriously transcribed without hyphen: "Louis Levy and his Gaumont British Symphony – Swing High, Swing Low (1937)". Youtube. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ "Louis Levy and his Gaumont British Symphony 'Everybody Dance' 1936". YouTube. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Citations

- ^ Evans & Humphreys 1997, p. 303.

- ^ "William Sewell". ChoralWiki. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ Martindale 1916, p. 323.

- ^ Sewell wrote the incidental music for The Cost of a Crown by Robert H. Benson, performed in 1908 for the centenary of St. Cuthbert's College, Ushaw.[3]

- ^ He co-edited a hymn book, published in 1913: Ould, Samuel Gregory; Sewell, William, eds. (1913). Book of Hymns with Tunes. London: Samuel Gregory Ould. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ Birmingham concert, 29 December 1907, including unaccompanied partsongs: "Music in Birmingham". The Musical Times. 49 (780): 112. 1 February 1908.

The Midland Gleemen, formerly known as Mr. William Sewell's Male-voice Choir...

Sewell conducted Cherubini's Requiem Mass No. 2 for Male chorus in Birmingham in 1909: "Music in Birmingham". The Musical Times. 50 (793): 186. 1 March 1909. JSTOR 905475. - ^ "Music in Sheffield and District". The Musical Times. 46 (752): 673. 1 October 1905. JSTOR 904414.

- ^ "Concerts &c". The Standard. London. 25 July 1910. p. 10d. Retrieved 9 May 2019. just above the last item.

- ^ "Concerts". The Standard. London. 7 December 1905. p. 9. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ "ConcertsRecitals &c". The Standard. London. 14 October 1904. p. 1g. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ She had played the Mozart A major concerto at a Prom in October 1904 with Henry Wood.[10]

- ^ "Aeolian Hall". The Standard. London. 18 December 1905. p. 10c. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ "Musical Notes". The Standard. London. 3 February 1906. p. 4d. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ "London Concerts". The Musical Times. 47 (757): 191. 1 March 1906. JSTOR 903515.

- ^ "Concert-Direction (Limited)". Morning Post. London. 10 March 1906. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

Concert-Direction (Limited). Directors—Messrs. Cowen and Sewell. Studios: 41–43, Maddox Street, W. (Tel. 2023 Gerrard.) Sole Agents for the British Symphony Orchestra. Conductor—Mr. William Sewell. The Directors are in Daily Attendance at the above studios.

- ^ Fifield 2017, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Plummer 2011, pp. 98–99.

- ^ "London Concerts". The Musical Times. 47 (759): 335. 1 May 1906. JSTOR 904513.

- ^ Dibble 2013, p. 70-71.

- ^ "Brightening the lives of the people on Sunday": the National Sunday League and Liberal Attitudes towards Concert Promotion in Victorian Britain" (abstract). Cambridge University Press. May 2019. pp. 37–59. ISBN 9781108628778. Retrieved 9 May 2019 – via Goldsmiths, University of London.

- ^ A previous chairman was Sir Joshua Walmsley. See also Gray, Will (15 September 2018). "Sir Josh and the National Sunday League – 1867". Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ "Musical Notes". The Standard. London. 7 April 1907. p. 5 col x. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ "Concerts, Recitals &c". The Standard. London. 20 October 1906. p. 1. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ "London Concerts: Crystal Palace Concerts". The Musical Times. 49 (779): 41. 1 January 1908. JSTOR 904561.

- ^ a b Lucas 2008, pp. 40–41.

- ^ "Lloyd Chandos – Elegy (Massenet)". Youtube. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ "Coliseum Sunday Concert". The Standard. London. 5 October 1908. p. 4d. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ "Programme for 'King Henry The Fifth', Imperial Theatre". Love Theatre Programmes. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ "Coliseum Sunday Concert". The Standard. London. 17 October 1908. p. 1d. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ "Alick Maclean Collection (1880–1960)". Concert Programmes. Retrieved 14 May 2019. Held at British Library, Collections.

- ^ "Queen's Hall Sunday Evenings". The Standard. London. 20 August 1910. p. 7d. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Lucas 2008, p. 41n.

- ^ The Referee, London, 3 April 1910. Page needed.

- ^ "Carmen Hill (born 1883), Singer". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ US soprano, performed in Leoni's opera Rip Van Winkle in 1907. "Ada Davies (1900)". The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Arakelyan, Ashot (30 November 2013). "Giuseppe Lenghi-Cellini (Tenor)". Forgotten Opera Singers. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Arakelyan, Ashot (5 August 2014). "Louis Graveure (Tenor)". Forgotten Opera Singers. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Concerts, Recitals &c". The Standard. London. 17 September 1910. p. 1c. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ a b c "The British Symphony Orchestra". The Musical Times. 60 (920): 557. 1 October 1919. JSTOR 3701785.

- ^ Potton 1920, p. 8.

- ^ a b Collins 1997, pp. 14–16.

- ^ a b Kalisch, Alfred (1 January 1920). "London Concerts". The Musical Times. 61 (923): 32–34. JSTOR 908483.

- ^ "Dalhousie Young". MusOpen. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ He also wrote a biography of Admiral John Jellicoe, Admiral Jellicoe by Arthur Applin. Retrieved 16 May 2019 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Potton 1920, pp. 2, 8–9.

- ^ a b Potton 1920, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e Boult 1973, p. 53.

- ^ "Back Matter". The Musical Times. 61 (928): 431. 1 June 1920. JSTOR 908617.

- ^ "Music in the Provinces: Nottingham and District". The Musical Times. 61 (923): 60. 1 January 1920. JSTOR 908497.

- ^ "Instrumental 78rpm Discs". Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Broadside for a Quinlan symphony concert". G. Gosen Rare Books & Old Paper. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Kalisch, Alfred (1 April 1920). "London Concerts – Elgar's Second Symphony". The Musical Times. 61 (926): 248. JSTOR 909617.

It is regrettable that the series of concerts of the British Symphony Orchestra had to be abandoned owing to lack of support. At the last concert February 23, the players gave an excellent performance of Hubert Bath's Symphonic Poem 'The Vision of Hannele' [1913], perhaps the best of his more ambitious works.

- ^ a b c d "Adrian Boult's orchestral outreach in East London: 'a bit of genuine decentralisation'". The Guardian, 16 February 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ Dates: 16 and 30 October, 20 November, 11 December 1920, 15 January 1921, 5 February, 9? and 23 March, 20, 21, 22, and 23 April. Source: "Concerts, &c". The Times. 2 October 1920. p. 8. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ The Times, 17 January 1921

- ^ "London: Kingsway Hall (1920–1964)". Concert Programmes. Retrieved 10 May 2019. "Kingsway Hall – eight programmes from the 1920-1921 season of Quinlan Subscription Concerts, the majority of which were given by the British Symphony Orchestra." Held at RCM Library.

- ^ Kalisch, Alfred (1 August 1920). "London Concerts". The Musical Times. 61 (930): 545–547. JSTOR 910316.

The respite will be brief, for the Promenade Concerts begin on August 14, and it may not be out of place to refer here to a new series of concerts by the British Symphony Orchestra, to be given on Saturday afternoons at the Kingsway Hall in Holborn.

- ^ "Boult Papers (1896–1969)". Concert Programmes. Retrieved 20 June 2019. Held at British Library.

- ^ Parlett, Graham (1999), A Catalogue of the Works of Sir Arnold Bax. Oxford: Clarendon/Oxford University Press, p. 120. Cited in Hannam, William B. (2008). Arnold Bax and the poetry of Tintagel (D. Phil thesis). University of Ohio.

- ^ Mercier, Anita (2008). Guilhermina Suggia, Cellist. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754661696.

- ^ Mitchell & Evans 2005, p. xix.

- ^ "Oxford Subscription Concerts (1920–30)". Concert Programmes. Retrieved 10 May 2019. Held at the Music Library of the Bodleian Library.

- ^ Kalisch, Alfred (1 March 1921). "London Concerts". The Musical Times. 62 (937): 178b. JSTOR 910932.

It is a very able study in atmosphere inspired by close sympathy with nature. There are some beautiful passages, but it somehow leaves the impression of being a fragment.

- ^ "Church and Organ Music". The Musical Times. 62 (937): 187. 1 March 1921. JSTOR 910940.

- ^ France, John (22 March 2009). "Sir Eugene Goossens: The Eternal Rhythm – tone poem". British Classical Music: The Land of Lost Content. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ Kalisch, Alfred (1 July 1921). "London Concerts". The Musical Times. 62 (941): 490. JSTOR 908238.

Taken all in all, this concert gave one a comfortable feeling that the present condition of modern creative music is extremely healthy.

- ^ Pech 2016, p. 30.

- ^ "Marie Hall: blue plaque in Cheltenham". Blue Plaque Places. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ Kalisch, Alfred (1 July 1921). "London Concerts". The Musical Times. 62 (941): 490. JSTOR 908238.

- ^ Boult 1973, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Kalisch, Alfred (1 August 1921). "Opéra Intime". The Musical Times. 62 (942): 569–570. JSTOR 910014.

- ^ Martin 1991, p. 7.

- ^ "Forum: Dr. Mordechai Sobol's program for the Parashat Bereshit". Behadrei Haredim (in Hebrew and English). Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "London Polytechnics and Peoples' Palaces". Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. XL (2). London: T. Fisher Unwin: 173–180. June 1890.

- ^ "London: People's Palace (1908–)". Concert Programmes. Retrieved 10 May 2019. Description: A collection of programmes from performances which took place in the People's Palace, Mile End Road. The majority of programmes are from orchestral concerts, with some programmes from opera, other theatrical events and oratorios. There is a collection of programmes from the 1st and 2nd series of concerts by the British symphony orchestra, conducted by Adrian Boult. Held at RCM library.

- ^ a b c Boult 1973, p. 54.

- ^ "The People's Palace". Queen Mary, University of London. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "Concerts". The Observer. 9 October 1921. p. 1. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

Admission Front Seats. Numbered. Reserved, 2s. 4d. (which may be booked), 1s 3d., and 8d. A few Free Seats. Next Concert, Sunday Oct. 30.

- ^ a b c "Orchestral". jolyon.com. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ Boult had made his very first gramophone recording with the Tommasini suite and the BSO on 5 & 16 November 1920 & on 21 July 1921.[79] See also British Symphony Orchestra discography.

- ^ W. McN. (1 December 1921). "London Concerts". The Musical Times. 62 (946): 847. JSTOR 908555.

- ^ Laurence, b. 25 May 1884, was a pupil of Holbrooke. Blom, Eric, ed. (1900). "Laurence, Frederick". Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Vol. 5: L–M (4th ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 87.

- ^ "London Concerts". The Musical Times. 63 (949): 190b. 1 March 1922. JSTOR 910099.

- ^ "Oxford Subscription Concerts (1920–1930)". Concert Programmes. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ Manning 2008, p. 403.

- ^ "Bach Choir". Concert Programmes. Retrieved 10 May 2019. Held at British Library, Music Collections.

- ^ "Aberystwyth Yesterday: Musical and Theatrical Ephemera". Ceredigion Archives. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "Occasional Notes". The Musical Times. 64 (964): 402–403. 1 June 1923. JSTOR 914100.

- ^ Westrup, Jack (October 1969). "Letters to the Editor". The Musical Times. 110 (1520): 1039. doi:10.2307/953420. JSTOR 953420.

- ^ "Clements, Charles Henry (1898–1983), musician". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ Parrott, Ian (December 1969). "Letters to the Editor: Elgar and Jerusalem". The Musical Times. 110 (1522): 1243. doi:10.2307/954527. JSTOR 954527.

- ^ "Lot 195. Antonio Stradivari – A violin known as The Penny, Cremona, circa 1700". Christies. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "1920 to 1923". Samuel Kutcher. 12 September 2010. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "Eugene Cruft". Contrabass.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2019-04-09. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ White, Lawrence William (April 2015). "MacDonagh, Thomas" (PDF). University College, Dublin. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "Discography Introduction: Gray data". Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "Front Matter". The Musical Times. 75 (1100): 866. 1 October 1934. JSTOR 918452.

Also includes an advertisement for a concert by the Royal Choral Society conducted by Malcolm Sargent, in memory of Delius, Elgar and Holst, who had all died in that same year. - ^ "Charles Hambourg". Worldcat. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "Tschaikov, Basil 'Nick', 1925-2016, musician". University of York: Borthwick Catalogue. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ "Colyer-Fergusson Collection, London – Venues G–P: Palladium". Concert Programmes. Retrieved 14 May 2019. Held at RCM.

- ^ "Charles Proctor Collection". Concert Programmes. Retrieved 14 May 2019. Held at RCM.

- ^ Sole recording (acoustic) of Proctor conducting works by F. J. Nettlefold, plus Albert Coates with Tod und Verklarung. "Retread: Coates' Tod und Verklarung". Narkive. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "The French Revolution 1 & 2". Disques Cinemusique (in French). Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "Music Box: Delerue-The French Revolution Expanded". Film Score. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "The World's Most Expensive Weddings: The Sahara Wedding ($128m)". iMarriages. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ "Band Announcements: ABBA News and Trivia". Revival ABBA Tribute Band. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ "Festival announces first acts: Never The Bride to headline". The Wokingham Paper. 26 February 2016. p. 25b.

- ^ "George Morton – Conductor & Arranger". GeorgeConducts. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "2018 Archive". GeorgeConducts. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "British Symphony Orchestra Tour of China". Miles Ushaw. 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ Giebert 2007, pp. 191–192.

- ^ "Obituary: Diana Wynne Jones". The Guardian. 27 March 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "Obituary: John Burrow". The Guardian. 29 October 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Wood, Henry J. (1946) [1938]. My Life of Music. London: Victor Gollancz. p. 68.

- ^ Bennett 2015, p. 84.

- ^ "The Lady in the Van". Imdb. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ British Pathé. "The British Women's Symphony Orchestra (1934)". Youtube. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Indigo Records. "British Youth Symphony Orchestra: Butterworth, Dvořák, Kabalevsky". Discogs. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "Carlos Guastavino (1912–2000)". Music of Argentina. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Blackmail at IMDb

- ^ Pendergast, Tom; Pendergast, Sara, eds. (2000). International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers, Volume 1 – Films (4th ed.). St. James Press. p. 142. ISBN 9781558624504.

- ^ Ades 2006, p. 9.

- ^ Ades, David (2006). "CD Liner notes for 'British Cinema Vol 2'" (PDF). Chandos Records. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Apparently the misspelled and unhyphenated "Gaumount British Symphony Orchestra" at IMDb.

- ^ "Television of the Week. Monday, October 4. Round the Film Studios: No. 1: Pinewood". Radio Times. (Online at BBC Genome). 57 (731): 19. 1 October 1937.

Viewers will meet Louis Levy either examining film in one of the editorial cutting rooms, or conducting a recording session with Jessie Matthews and the Gaumont-British Symphony Orchestra.

NB Click highlighted passage for full text. - ^ The 'Gaumont-British Symphony Orchestra', with Levy conducting, featured in two BBC films made at Pinewood Studios for its Round the Film Studios TV series, aired on 30 September and 4 October 1937.[124][125]

Bibliography

[edit]- Bennett, Alan (2015). The Lady in the Van: The Complete Edition. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 9780571326396.

- Boult, Adrian (1973). My Own Trumpet. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0241024455.

- Collins, L. J. (1997). Theatre at War, 1914-18. Springer. ISBN 9780230372221.

- Dibble, Jeremy (2013). Hamilton Harty: Musical Polymath. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843838586.

- Evans, Robert; Humphreys, Maggie, eds. (1997). Dictionary of Composers for the Church in Great Britain and Ireland. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781441137968.

- Fifield, Christopher (2017). Ibbs and Tillett: The Rise and Fall of a Musical Empire. Routledge. ISBN 9781351125727.

- Giebert, Stefanie (November 2007). Elfland Revisited: A Comparative Study of Late Twentieth Century Adaptations of Two Traditional Ballads (Ph.D thesis). University of Trier.

- Lucas, John (2008). Thomas Beecham: An Obsession with Music. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843834021.

- Manning, David, ed. (2008). "British Choral Music and Dvorak, Stabat Mater". Vaughan Williams on Music. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195182392.

- Martin, Timothy (1991). Joyce and Wagner: A Study of Influence. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521394871.

- Martindale, Cyril C. (1916). The life of Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- Mitchell, Mark; Evans, Allan, eds. (2005). Moriz Rosenthal in Word and Music: A Legacy of the Nineteenth Century. Indiana University Press. p. xix. ISBN 9780253111661.

- Pech, Kay (2016). "Women and the Violin: A history of women violinists born before 1950, music written by women for the violin, and societal attitudes toward women violinists" (Revised ed.). Cerritos, California.

- Plummer, Declan (March 2011). 'Music Based On Worth': The Conducting Career of Sir Hamilton Harty (PDF) (D. Phil thesis). Queen's University of Belfast. pp. 98-99 [pdf 129].

- Potton, Edward (1920). A record of the United Arts Rifles, 1914-1919. London: Alexander Moring.

External links

[edit]For recordings of the various orchestras on Youtube, see British Symphony Orchestra discography

- William Sewell

- Full score of Sewell, William. "Mass of St. Philip Neri" (PDF). ChoralWiki. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- Sewell, William. "Salve Regina". Youtube. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "Pangamus Nerio – Vesper Hymn of Saint Philip Neri". Youtube. (Composed in 1895 by William Sewell). Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- Other

KSF

KSF