Carbocyclic nucleoside

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 8 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 8 min

Carbocyclic nucleosides (also referred to as carbanucleosides) are nucleoside analogues in which a methylene group has replaced the oxygen atom of the furanose ring.[1] These analogues have the nucleobase attached at a simple alkyl carbon rather than being part of a hemiaminal ether linkage. As a result, they have increased chemical stability. They also have increased metabolic stability because they are unaffected by phosphorylases and hydrolases that cleave the glycosidic bond between the nucleobase and furanose ring of nucleosides. They retain many of the biological properties of the original nucleosides with respect to recognition by various enzymes and receptors.

Carbocyclic nucleosides were originally limited to a five-membered ring system, matching the ring-size of the nucleosides; however, this term has been broadened to three-, four-, and six-membered rings.[2][3][4]

Natural products

[edit]The 5-membered ring carbocyclic nucleosides aristeromycin, the analog of adenosine, and neplanocin A, the cyclopentene analog of aristeromycin, have been isolated from natural sources. They both exhibit significant biological activity as antiviral and antitumour agents.[1]

Classes

[edit]A large number of novel carbocyclic nucleosides of pyrimidines and purines have been prepared, and many of these compounds are endowed with interesting biological activities.

Pyrimidine carbocyclic nucleosides

[edit]The cyclopentenylcytosine (CPE-C) was developed as a potent antitumor and antiviral agent (phase 1 trials)[5] and exhibited potent anti-orthopoxvirus as well as anti-West Nile virus activities.[3] Carbocyclic (E)-5-(2-bromovinyl)-2-deoxyuridine( (+) C-BVDU) GR95168 possesses activity against herpes simplex virus type l (HSV-1) and varicella zoster virus (VZV, chicken pox and shingles) in-vitro and in-vivo.[6]

Purine carbocyclic nucleosides

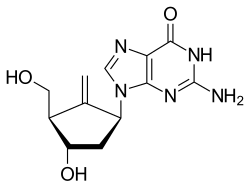

[edit]The two guanine antiviral carbocyclic nucleosides, the anti-HIV agent abacavir and the anti-hepatitis B agent entecavir, are reverse-transcriptase inhibitors. Abacavir, was developed from racemic (±)-carbovir which was reported in 1988 by Robert Vince as the first carbocyclic nucleoside analogue to show potent activity against HIV with low cytotoxicity.[7] The (-) enantiomer of carbovir was later shown to be the biologically active form for inhibition of HIV.[8] However carbovir's low aqueous solubility and poor oral bioavailability, as well as inefficient central nervous system penetration prevented it from further developing as an anti-HIV agent. These difficulties were overcome by investigating prodrug analogues of (-) carbovir which lead to the 6-cyclopropylamino-2-aminopurine nucleoside abacavir,[9] which was approved in 1998 by the FDA for the treatment of HIV infection.

- Antiviral Carbocyclic Purine nucleosides

-

(-)Carbovir

-

Carbocyclic 2′-ara-fluoro-guanosine

Entecavir, a guanosine analog, was reported in 1997 as a potent and selective inhibitor for the hepatitis B virus,[10] and approved by the FDA in March 2005 for oral treatment of hepatitis B infection. The fluorocarbocyclic nucleoside carbocyclic 2′-ara-fluoro-guanosine was reported in 1988 as the first example of a carbocyclic analogue of an unnatural nucleoside to exhibit greater anti-herpes activity against the herpesviruses HSV-1 and HSV-2 in-vitro than its furanose parent.[11]

Synthesis

[edit]There are two approaches used in the synthesis of carbocyclic nucleosides.[12] Linear approaches to chiral carbocyclic nucleosides 2 rely on the construction of the heterocyclic base onto a suitable protected chiral cyclopentylamine (1 → 2). In the convergent approach the intact heterocyclic base is coupled directly to a suitably protected functionalised carbocyclic moiety (3 → 2).

History

[edit]- 1966: First described synthesis of the racemic (±) carbocyclic analogue of adenosine.[13]

- 1968: The (-) enantiomer, named aristeromycin. was isolated as a metabolite of Streptomyces citricolor.[14]

- 1981: Isolation of the neplanocin family of carbocyclic nucleosides and in particular the cyclopentenyl derivative neplanocin A from Ampukwiella regularis [15]

- 1983: The first enantiospecific synthesis of (-) aristeromycin and (-) neplanocin A [16]

- 1986: The first comprehensive review of carbocyclic nucleosides including the linear chemical syntheses and the biological properties of these early racemic analogues and of the natural products aristeromycin and neplanocin A.[1]

- 1988: The first fluorocarbocyclic nucleoside C-AFG synthesised that was 1000-fold more active than the furanose parent nucleoside against HSV-1 and HSV-2 in-vitro.[11]

- 1988: Review of Glaxo's synthesis of fluorocarbocyclic nucleosides [17]

- 1988: (±)-Carbovir first reported with potent anti-HIV activity and low cytotoxicity [7]

- 1992: First comprehensive review of the synthesis of chiral carbocyclic nucleosides.[12]

- 1994: A review covering the racemic cyclopentyl carbocyclic nucleosides [18] was broadened to include the bioactivity of carbocyclic nucleosides in 1998 [19]

- 1997: Abacavir, prodrug of (-)Carbovir reported,[9] approved by the FDA in December 1998, for the treatment of HIV infection under the trade name of Ziagen™.

- 1997: First report of Entecavir (BMS-200475) as potent and selective anti-hepatitis B inhibitor,[10] approved by the FDA in March 2005 for oral treatment of hepatitis B infection. trade names Baraclude or Entaliv.

- 1998: Review of new developments in the enantioselective synthesis of cyclopentyl carbocyclic nucleosides.[20]

- 2003: Review of new progresses in the enantioselective synthesis and biological properties of carbocyclic nucleosides including 3, 4 and 6 membered carbocyclic rings.[4]

- 2011: Review covers the most recent advances in the synthesis and biological activity of carbocyclic nucleosides up to September 2010.[3]

- 2013: Two reviews of the most representative methods of asymmetric synthesis of carbocyclic nucleosides since 1998 [21][22]

- 2014: Review of the synthesis of carbocyclic nucleosides involving ring-closing metathesis (RCM) as a key step.[23]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Marquez VE, Lim MI (January 1986). "Carbocyclic nucleosides". Medicinal Research Reviews. 6 (1): 1–40. doi:10.1002/med.2610060102. PMID 3512934. S2CID 221956841.

- ^ Zhu XF (March 2000). "The latest progress in the synthesis of carbocyclic nucleosides". Nucleosides, Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids. 19 (3): 651–690. doi:10.1080/15257770008035015. PMID 10843500. S2CID 43360920.

- ^ a b c Wang J; Rawal RK; Chu CK (August 2011). "Recent Advances in Carbocyclic Nucleosides: Synthesis and Biological Activity". In L-H Zhang, Z Xi and J Chattopadhyaya (ed.). Medicinal Chemistry of Nucleic Acids. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–100. ISBN 9780470596685.

- ^ a b Rodrguez JB, Comin MJ (March 2003). "New progresses in the enantioselective synthesis and biological properties of carbocyclic nucleosides". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 3 (2): 95–114. doi:10.2174/1389557033405331. hdl:11336/90989. PMID 12570843.

- ^ Marquez, V. E. (April 1996). "CARBQCYCLIC NUCLEOSIDES". In E. De Clercq (ed.). Advances in Antiviral Drug Design. Vol. 2. JAI Press Inc. pp. 89–146. ISBN 1-55938-693-2.

- ^ Cameron JM (December 1993). "New antiherpes drugs in development". Reviews in Medical Virology. 3 (4): 225–236. doi:10.1002/rmv.1980030406. S2CID 84289059.

- ^ a b Vince R, Hua M, Brownell J, Daluge S, Lee F, Shannon WM, Lavelle GC, Qualls J, Weislow OS, Kiser R, Canonico PG (October 1988). "Potent and selective activity of a new carbocyclic nucleoside analog (carbovir: NSC 614846) against human immunodeficiency virus in vitro". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 156 (2): 1046–1053. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(88)80950-1. PMID 2847711.

- ^ Carter SG, Kessler JA, Rankin CD (June 1990). "Activities of (-)-carbovir and 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine against human immunodeficiency virus in vitro". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 34 (6): 1297–1300. doi:10.1128/AAC.34.6.1297. PMC 171808. PMID 2393292.

- ^ a b Daluge SM, Good SS, Faletto MB, Miller WH, St Clair MH, Boone LR, Tisdale M, Parry NR, Reardon JE, Dornsife RE, Averett DR (May 1997). "1592U89, a novel carbocyclic nucleoside analog with potent, selective anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 41 (5): 1082–1093. doi:10.1128/AAC.41.5.1082. PMC 163855. PMID 9145874.

- ^ a b Bisacchi GS, Chao ST, Bachard C, Daris JP, Innaimo S, Jacobs GA, Kocy O, Lapointe P, Martel A, Merchant ZL, Slusarchyk WA (January 1997). "BMS-200475, a novel carbocyclic 2′-deoxyguanosine analog with potent and selective anti-hepatitis B virus activity in vitro". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 7 (2): 127–132. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(96)00594-X.

- ^ a b Borthwick AD, Butt S, Biggadike K, Exall AM, Roberts SM, Youds PM, Kirk BE, Booth BR, Cameron JM, Cox SW, Marr CL (1988). "Synthesis and enzymatic resolution of carbocyclic 2-ara-fluoro-guanosine: a potent new anti-herpetic agent". Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications (10): 656–658. doi:10.1039/C39880000656.

- ^ a b Borthwick AD, Biggadike K (1992). "Synthesis of chiral carbocyclic nucleosides". Tetrahedron. 48 (4): 571–623. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)88122-9.

- ^ Shealy YF, Clayton JD (August 1966). "9-[β-DL-2α, 3α-Dihydroxy-4β-(hydroxymethyl)-cyclopentyl] adenine, the Carbocyclic Analog of Adenosine". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 88 (16): 3885–3887. doi:10.1021/ja00968a055.

- ^ Kusaka T, Yamamoto H, Shibata M, Muroi M, Kishi T, Mizuno K (1968). "Streptomyces citricolor nov. sp. and a new antibiotic, aristeromycin". The Journal of Antibiotics. 21 (4): 255–263. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.21.255. PMID 5671989.

- ^ Yaginuma S, Muto N, Tsujino M, Sudate Y, Hayashi M, Otani M (1981). "Studies on neplanocin A, new antitumor antibiotic. I. Producing organism, isolation and characterization". The Journal of Antibiotics. 34 (4): 359–366. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.34.359. PMID 7275815.

- ^ Arita M, Adachi K, Ito Y, Sawai H, Ohno M (June 1983). "Enantioselective synthesis of the carbocyclic nucleosides (-)-aristeromycin and (-)-neplanocin A by a chemicoenzymatic approach". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 105 (12): 4049–4055. doi:10.1021/ja00350a050.

- ^ Roberts SM; Biggadike K; Borthwick AD; Kirk BE (1988). "Synthesis of Some Antiviral Carbocyclic Nucleosides". In P R Leeming (ed.). Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. London: Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 172–188. ISBN 0-85186-726-X.

- ^ Agrofoglio L, Suhas E, Farese A, Condom R, Challand SR, Earl RA, Guedj R (December 1994). "Synthesis of carbocyclic nucleosides". Tetrahedron. 50 (36): 10611–10670. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)89258-9.

- ^ Agrofoglio LA; Challand SR (1998). "The chemistry of carbocyclic nucleosides, Biological activity of carbocyclic nucleosides". In Agrofoglio LA, Challand SR (ed.). Acyclic, Carbocyclic and L-nucleosides. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 174–284. ISBN 978-94-010-3734-1.

- ^ Crimmins MT (August 1998). "New developments in the enantioselective synthesis of cyclopentyl carbocyclic nucleosides". Tetrahedron. 54 (32): 9229–9272. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00320-2.

- ^ Leclerc E (February 2013). "Chemical synthesis of carbocyclic analogues of nucleosides". Chemical Synthesis of Nucleoside Analogues. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 535–604. doi:10.1002/9781118498088.ch12. ISBN 9781118498088.

- ^ Boutureira O, Matheu MI, Díaz Y, Castillón S (March 2013). "Advances in the enantioselective synthesis of carbocyclic nucleosides". Chemical Society Reviews. 42 (12): 5056–5072. doi:10.1039/C3CS00003F. PMID 23471263.

- ^ Mulamoottil VA, Nayak A, Jeong LS (July 2014). "Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Carbocyclic Nucleosides via Ring-Closing Metathesis". Asian Journal of Organic Chemistry. 3 (7): 748–761. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201402032.

KSF

KSF