Cargo ship

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 20 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 20 min

A cargo ship or freighter is a merchant ship that carries cargo, goods, and materials from one port to another. Thousands of cargo carriers ply the world's seas and oceans each year, handling the bulk of international trade. Cargo ships are usually specially designed for the task, often being equipped with cranes and other mechanisms to load and unload, and come in all sizes. Today, they are almost always built of welded steel, and with some exceptions generally have a life expectancy of 25 to 30 years before being scrapped.[citation needed]

Definitions

[edit]

| Admiralty (maritime) law |

|---|

| History |

| Features |

| Contract of carriage / charterparty |

| Parties |

| Judiciaries |

| International organizations |

| International conventions |

|

| International Codes |

The words cargo and freight have become interchangeable in casual usage. Technically, "cargo" refers to the goods carried aboard the ship for hire, while "freight" refers to the act of carrying of such cargo, but the terms have been used interchangeably for centuries.

Generally, the modern ocean shipping business is divided into two classes:

- Liner business: typically (but not exclusively) container vessels (wherein "general cargo" is carried in 20-or-40-foot (6.1 or 12.2 m) containers), operating as "common carriers", calling at a regularly published schedule of ports. A common carrier refers to a regulated service where any member of the public may book cargo for shipment, according to long-established and internationally agreed rules.

- Tramp-tanker business: generally this is private business arranged between the shipper and receiver and facilitated by the vessel owners or operators, who offer their vessels for hire to carry bulk (dry or liquid) or break bulk (cargoes with individually handled pieces) to any suitable port(s) in the world, according to a specifically drawn contract, called a charter party.

Larger cargo ships are generally operated by shipping lines: companies that specialize in the handling of cargo in general. Smaller vessels, such as coasters, are often owned by their operators.

Types

[edit]Cargo ships/freighters can be divided into eight groups, according to the type of cargo they carry. These groups are:

- Feeder ship

- General cargo vessels

- Container ships

- Tankers

- Dry bulk carriers

- Multi-purpose vessels

- Reefer ships

- Roll-on/roll-off vessels.

Rough synopses of cargo ship types

[edit]- General cargo vessels carry packaged items like chemicals, foods, furniture, machinery, motor- and military vehicles, footwear, garments, etc.

- Container ships (sometimes spelled containerships) are cargo ships that carry all of their load in truck-size intermodal containers, in a technique called containerization. They are a common means of commercial intermodal freight transport and now carry most seagoing non-bulk cargo. Container ship capacity is measured in twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU).

- Tankers carry petroleum products or other liquid cargo.

- Dry bulk carriers carry coal, grain, ore and other similar products in loose form.

- Multi-purpose vessels, as the name suggests, carry different classes of cargo – e.g. liquid and general cargo – at the same time.

- A Reefer, Reefer ships (or Refrigerated) ship is specifically designed[1] and used for shipping perishable commodities which require temperature-controlled, mostly fruits, meat, fish, vegetables, dairy products and other foodstuffs.

- Roll-on/roll-off (RORO or ro-ro) ships are designed to carry wheeled cargo, such as cars, trucks, semi-trailer trucks, trailers, and railroad cars, that are driven on and off the ship on their own wheels.

- Timber (Lumber) carriers that transport lumber, logs and related wood products.[2]

Specialized cargo ship types

[edit]Specialized types of cargo vessels include container ships and bulk carriers (technically tankers of all sizes are cargo ships, although they are routinely thought of as a separate category). Cargo ships fall into two further categories that reflect the services they offer to industry: liner and tramp services. Those on a fixed published schedule and fixed tariff rates are cargo liners. Tramp ships do not have fixed schedules. Users charter them to haul loads. Generally, the smaller shipping companies and private individuals operate tramp ships. Cargo liners run on fixed schedules published by the shipping companies. Each trip a liner takes is called a voyage. Liners mostly carry general cargo. However, some cargo liners may carry passengers also. A cargo liner that carries 12 or more passengers is called a combination or passenger-run-cargo line.

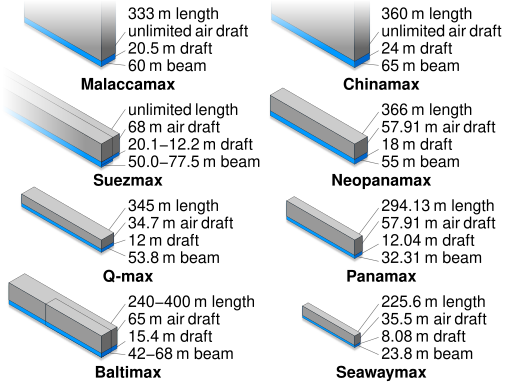

Size categories

[edit]Cargo ships are categorized partly by cargo or shipping capacity (tonnage), partly by weight (deadweight tonnage DWT), and partly by dimensions. Maximum dimensions such as length and width (beam) limit the canal locks a ship can fit in, water depth (draft) is a limitation for canals, shallow straits or harbors and height is a limitation in order to pass under bridges. Common categories include:

- Dry cargo

- Small Handy size, carriers of 20,000–28,000 DWT

- Seawaymax, 28,000 DWT the largest vessel that can traverse the St Lawrence Seaway. These are vessels less than 225.6 metres (740 ft) in length, 23.8 metres (78 ft) wide, and have a draft less than 8.08 metres (26.51 ft) and a height above the waterline no more than 35.5 metres (116 ft).

- Handy size, carriers of 28,000–40,000 DWT

- Handymax, carriers of 40,000–50,000 DWT

- Panamax, the largest size that can traverse the original locks of the Panama Canal, a 294.13 m (965.0 ft) length, a 32.2 m (106 ft) width, and a 12.04 m (39.5 ft) draft as well as a height limit of 57.91 m (190.0 ft). Average deadweight between 65,000 DWT and 80,000 DWT, with cargo intake limited to 52,500 DWT.

- Neopanamax, upgraded Panama locks with 366 m (1,201 ft) length, 55 m (180 ft) beam, 18 m (59 ft) draft, 120,000 DWT[3]

- Capesize, vessels larger than Suezmax and Neopanamax, and must traverse Cape Agulhas and Cape Horn to travel between oceans, dimension: about 170,000 DWT, 290 m (950 ft) long, 45 m (148 ft) beam (wide), 18 m (59 ft) draft (under water depth).[4]

- Chinamax, carriers of 380,000–400,000 DWT up to 24 m (79 ft) draft, 65 m (213 ft) beam and 360 m (1,180 ft) length; these dimensions are limited by port infrastructure in China

- Baltimax, limited by the Great Belt. The limit is a draft of 15.4 m (51 ft) and an air draft of 65 m (213 ft), which is limited by the clearance of the east bridge of the Great Belt Fixed Link. The length can be around 240 m (790 ft) and the width around 42 m (138 ft). This gives a weight of around 100,000 metric tons.

- Wet cargo

- Aframax, oil tankers between 75,000 and 115,000 DWT. This is the largest size defined by the average freight rate assessment (AFRA) scheme.

- Q-Max, liquefied natural gas carrier for Qatar exports. A ship of Q-Max size is 345 m (1,132 ft) long and measures 53.8 m (177 ft) wide and 34.7 m (114 ft) high, with a shallow draft of approximately 12 m (39 ft).[5][6]

- Suezmax, typically ships of about 160,000 DWT, maximum dimensions are a beam of 77.5 m (254 ft), a draft of 20.1 m (66 ft) as well as a height limit of 68 m (223 ft) can traverse the Suez Canal

- VLCC (Very Large Crude Carrier), supertankers between 150,000 and 320,000 DWT.

- Malaccamax, ships with a draft less than 20.5 m (67.3 ft) that can traverse the Strait of Malacca, typically 300,000 DWT.

- ULCC (Ultra Large Crude Carrier), enormous supertankers between 320,000 and 550,000 DWT

The TI-class supertanker is an Ultra Large Crude Carrier, with a draft that is deeper than Suezmax, Malaccamax and Neopanamax. This causes Atlantic/Pacific routes to be very long, such as the long voyages south of Cape of Good Hope or south of Cape Horn to transit between Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

Lake freighters built for the Great Lakes in North America differ in design from sea water–going ships because of the difference in wave size and frequency in the lakes. A number of these ships are larger than Seawaymax and cannot leave the lakes and pass to the Atlantic Ocean, since they do not fit the locks on the Saint Lawrence Seaway.

History

[edit]

The earliest records of waterborne activity mention the carriage of items for trade; the evidence of history and archaeology shows the practice to be widespread by the beginning of the 1st millennium BC, and as early as the 14th and 15th centuries BC small Mediterranean cargo ships like those of the 15-metre (50 ft) long Uluburun ship were carrying 20 tons of exotic cargo; 11 tons of raw copper, jars, glass, ivory, gold, spices, and treasures from Canaan, Greece, Egypt, and Africa. The desire to operate trade routes over longer distances, and throughout more seasons of the year, motivated improvements in ship design during the Middle Ages.

Before the middle of the 19th century, the incidence of piracy resulted in most cargo ships being armed, sometimes quite heavily, as in the case of the Manila galleons and East Indiamen. They were also sometimes escorted by warships.

Piracy

[edit]Piracy is still quite common in some waters, particularly in the Malacca Straits, a narrow channel between Indonesia and Singapore / Malaysia, and cargo ships are still commonly targeted. In 2004, the governments of those three nations agreed to provide better protection for the ships passing through the Straits. The waters off Somalia and Nigeria are also prone to piracy, while smaller vessels are also in danger along parts of the South American coasts, Southeast Asian coasts, and near the Caribbean Sea.[7][8]

Vessel prefixes

[edit]A category designation appears before the vessel's name. A few examples of prefixes for naval ships are "USS" (United States Ship), "HMS" (Her/His Majesty’s Ship), "HMCS" (Her/His Majesty's Canadian Ship) and "HTMS" (His Thai Majesty's Ship), while a few examples for prefixes for merchant ships are "RMS" (Royal Mail Ship, usually a passenger liner), "MV" (Motor Vessel, powered by diesel), "MT" (Motor Tanker, powered vessel carrying liquids only) "FV" Fishing Vessel and "SS" (Screw Steamer, driven by propellers or screws, often understood to stand for Steamship). "TS", sometimes found in first position before a merchant ship's prefix, denotes that it is a turbine steamer.

Famous cargo ships

[edit]Famous cargo ships include the 2,710 Liberty ships of World War II, partly based on a British design. Liberty ship sections were prefabricated in locations across the United States and then assembled by shipbuilders in an average of six weeks, with the record being just over four days. These ships allowed the Allies in World War II to replace sunken cargo vessels at a rate greater than the Kriegsmarine's U-boats could sink them, and contributed significantly to the war effort, the delivery of supplies, and eventual victory over the Axis powers. Liberty ships were followed by the faster Victory ships. Canada built Park ships and Fort ships to meet the demand for the Allies shipping. The United Kingdom built Empire ships and used US Ocean ships. After the war many of the ships were sold to private companies. The Ever Given is a ship that was lodged into the Suez Canal from March 25 to 28, 2021, which caused a halt on maritime trade.[9][10][11][12] The MV Dali, which collided with the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore, Maryland, United States, on 26 March 2024, causing a catastrophic structural failure of the bridge that resulted in at least six deaths.[13][14]

Pollution

[edit]Due to its low cost, most large cargo vessels are powered by bunker fuel, also known as heavy fuel oil, which contains higher sulphur levels than diesel.[15] This level of pollution is increasing:[16] with bunker fuel consumption at 278 million tonnes per year in 2001, it is projected to be at 500 million tonnes per year in 2020.[17] International standards to dramatically reduce sulphur content in marine fuels and nitrogen oxide emissions have been put in place. Among some of the solutions offered is changing over the fuel intake to clean diesel or marine gas oil, while in restricted waters and cold ironing the ship while it is in port. The process of removing sulphur from the fuel impacts the viscosity and lubricity of the marine gas oil though, which could cause damage in the engine fuel pump. The fuel viscosity can be raised by cooling the fuel down.[18] If the various requirements are enforced, the International Maritime Organization's marine fuel requirement will mean a 90% reduction in sulphur oxide emissions;[19] whilst the European Union is planning stricter controls on emissions.[20]

Environmental impact

[edit]Cargo ships have been reported to have a possible negative impact on the population of whale sharks. Smithsonian Magazine reported in 2022 that whale sharks, the largest species of fish, have been disappearing mysteriously over the past 75 years, with research pointing to cargo ships and large vessels as the likely culprits.[21] A study involving over 75 researchers highlighted the danger posed to whale sharks by shipping activities in various regions, including Ecuador, Mexico, Malaysia, the Philippines, Oman, Seychelles, and Taiwan.[22]

See also

[edit]- Classification of European Inland Waterways—standards determining vessel sizes on rivers and canals of Europe

- MARPOL 73/78—related to pollution: "Amended Regulation 14 concerns mandatory fuel oil change over procedures for vessels entering or leaving SECA areas and FO sulphur limits."

- Merchant Navy (United Kingdom)

- Merchant vessel

- Ship transport

- United States Merchant Marine

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Article: from publication on types of Reefer Ships by Capt. Pawanexh Kohli" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2009.

- ^ "Understanding Lumber Carrier Vessels". Marine Insight. July 13, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ "The New Panamax; 13,200-TEU Containership, 120,000 dwt Bulk Carrier". Shipping Research and Finance. September 12, 2012.

- ^ "Types of vessel sizes and Bulk Carriers - A One Maritime".

- ^ Cho Jae-eun (July 9, 2008). "Korea launches new tankers. Qatar-bound Mozah is the biggest LNG carrier ever built". Korea JoongAng Daily. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ Curt, Bob (March 29, 2004). Marine Transportation of LNG (PDF). Intertanko Conference. Maritime Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- ^ "Documentaries - Pirates - Part Two". BBC World Service.

- ^ "Pirates, Warlords and Rogue Fishing Vessels in Somalia's Unruly Seas".

- ^ MARAD, Victory Ship, U.S. Maritime Commission design type VC2-S-AP2

- ^ "Canada Parks History and culture". Archived from the original on July 29, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ "British Order Sixty 10,000 Dwt. Cargo Steamers". Pacific Marine Review. Consolidated 1941 issues (January 1941). Pacific American Steamship Association/Shipowners' Association of the Pacific Coast: 42–43. 1941. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ Mitchell, William Harry & Sawyer, Leonard Arthur (1990). The Empire Ships (2nd ed.). London, New York, Hamburg, Hong Kong: Lloyd's of London Press Ltd. ISBN 1-85044-275-4.

- ^ Ng, Greg (March 26, 2024). "'Key Bridge is gone': Ship strike destroys bridge, state of emergency declared". WBAL. Archived from the original on March 26, 2024. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ "6 workers presumed dead after cargo ship crash levels Baltimore bridge". NBC News. March 27, 2024. Retrieved March 27, 2024.Archived 26 March 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Vidal, John (April 9, 2009), "Health risks of shipping pollution have been 'underestimated'", The Guardian, retrieved June 11, 2012

- ^ Pollution impact from ships - article on Cold ironing

- ^ Global Trade and Fuels Assessment— Additional ECA Modeling Scenarios (PDF), United States Environmental Protection Agency, May 2009, EPA-420-R-09-009, archived from the original (PDF) on August 1, 2013, retrieved June 11, 2012

- ^ "MGO Cooler". heinenhopman.com. September 12, 2016.

- ^ Air Pollution from Ships (PDF), November 2011, archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2013, retrieved June 11, 2012

- ^ "EU launches attempt to deliver shipping emissions trading scheme". www.businessgreen.com. January 24, 2012.

- ^ Kuta, Sarah. "Cargo Ships Are Killing Whale Sharks". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ Hobson, Melissa (May 23, 2024). "The world's largest fish are vanishing without a trace". National Geographic. Archived from the original on May 24, 2024. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

General references

[edit]- Greenway, Ambrose (2009). Cargo Liners: An Illustrated History. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 9781848320062.

KSF

KSF