Civil funeral celebrant

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

Funeral ritual at graveside | |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

Occupation type | Vocational |

Activity sectors | Cultural and social infrastructure |

| Description | |

| Competencies | Public speaking, creative writing (including eulogies), literary and music knowledge /resources, inter-personal skill and empathy, organisational skills |

Education required | Study and field work (by mentoring) to gain competencies (as above) |

Related jobs | Officiants, clergy |

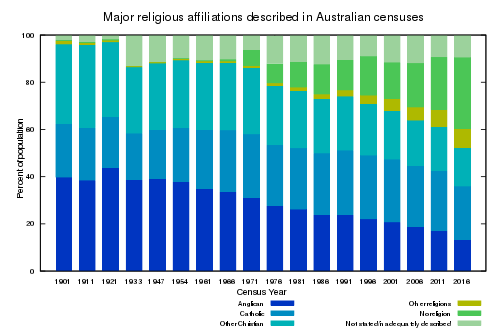

A civil funeral celebrant is a person who officiates at funerals which are not closely connected with religious beliefs and practises. They are analogous to civil celebrants for marriage ceremonies. Civil celebrant funerals began in Australia in 1975.[1] As secular (civil) wedding ceremonies became accepted, first in Australia and then in other Western countries,[2][3] a similar process for funerals has since been established in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States.[4]: 148–192 [5][6][7][1]: 56 [8][4] Civil funeral celebrants are often also civil marriage ceremony celebrants.

Description

[edit]A civil funeral celebrant provides funerals for people who do want a religious ceremony and those who have religious beliefs but do not want to be buried or cremated from a church or other religious building. People often choose civil celebrants because they want a professional person to co-create a service centred on the deceased person's life but without any formal religious ceremony.[4]: 164–165 In celebrant ceremonies all decisions about the details of the ceremony are made by the family of the deceased in consultation with the celebrant. Best practice is for celebrants to interview the family, prepare and check the eulogy, brief those giving reminiscences and provide resources and suggestions that will assist the family choose aspects of the ceremony such as the music, video and photo presentations, quotations (poetry and prose) and symbols.[4]: 164 Sometimes a rehearsal is indicated for a funeral. More often a planning session ensures that the ceremony is as wanted. Celebrants work with funeral directors[9] but are usually the principal officiant at the ceremony.[9] The celebrants do not officiate from any doctrinal belief or unbelief on the principle that their own beliefs and values are not relevant.[9]: 148–154

Early history

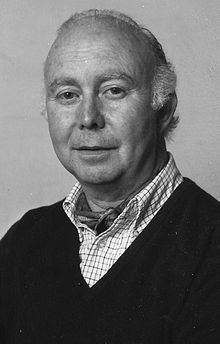

[edit]An acknowledged pioneer of civil celebrancy, Dally Messenger III, claimed to have officiated at the first funeral celebrant ceremony. This was in the sense that the client sought a service from Messenger, as a government appointed civil celebrant and as a professional ceremony provider.[4]: 157 There had occasionally been secular funeral ceremonies before this date, but they were extremely rare and informal, e.g. some words spoken at the graveside by members of the Communist party. In general, funerals were considered to be the province of clergy - even for unbelievers. For example, many funerals for non-believers were simply the playing of music.[4]: 151

Dally Messenger III records that this first celebrant funeral was for Helen Francis (née Grieves) on 2 July 1975 at the Le Pine Funeral Parlour in Ferntree Gully, a suburb of Melbourne in the state of Victoria. Helen Francis was a young woman who had engaged Messenger as a celebrant for her wedding to Roy Francis some four weeks previously.[4]: 157 Roy Francis convinced Messenger that just as his wife was entitled to a civil celebrant marriage, she was similarly entitled to a civil celebrant funeral. Some 200 people attended and many urged Messenger to continue the work as "much more important than weddings". Messenger credits Dennis Perry, then brother in law of Helen Francis, as being a decisive influence.[9]

Inaugural Australian association of funeral celebrants

[edit]Support from the funeral industry and clergy

[edit]

From this time on some marriage celebrants began to quietly and carefully officiate at funerals when they were asked to do so. In 2007, a group of authorised marriage celebrants in Australia formed a not-for-profit association - Funeral Celebrants Association Australia.[11] It remains the only association in Australia dedicated to funeral celebrancy as at 2024.

Controversy among celebrants

[edit]These innovations soon produced a bitter controversy. In a time when death and funerals were almost taboo subjects, the majority of marriage celebrants were viscerally opposed to being associated with funerals. Most, supported by the public servants of the Commonwealth's Attorney-General's Department, viewed the situation of civil marriage celebrants also being funeral celebrants as "using their appointment as civil marriage celebrants, to commercially exploit vulnerable people in their time of grief".[4]: 88–91, 162

Most of those marriage celebrants who had attended the inaugural meeting then withdrew their support. The few "marriage celebrant associations" declared their opposition to funerals. However, Lionel Murphy, then a judge of the High Court of Australia, encouraged Messenger to go out into the "highways and byways" and find non-marriage celebrants to fulfil the societal need.[4]: 161

Murphy urged Messenger and his colleagues to prepare each ceremony well, to charge a reasonable fee to ensure long term sustainability, and to see the civil ceremony as a cultural bridge between ordinary people and the rich world of the visual and performing arts - especially music,[12] English literature, and poetry.[4]: 99

Pioneer civil funeral celebrants

[edit]

The few marriage celebrants of that time (1975-1976) involved - notably Dally Messenger III and Marjorie Messenger - were in the years and months following (to 1980) joined by non-marriage celebrants Brian McInerney, Diane Storey, Dawn Dickson, Jean Nugent, Ken Woodburn and Jan Tully. A decisive influence later was marriage celebrant, mayor of Croydon and public advocate Rick Barclay. Messenger credits these persons with establishing the profession in Melbourne, and subsequently throughout the western world.[4]: 147–192

In 1980, the media noted that a surge in demand for civil funeral celebrants had become apparent. In an article on Jean Nugent, characterised as the Mornington Peninsula's "first civil funeral celebrant", Tony Harrington headlined that "Business grows for civil hatchers and dispatchers".[13]: 8

Setting standards and prices

[edit]Standards

[edit]As with marriage celebrants, public acceptance of funeral celebrants was enthusiastic and rapid. The early celebrants reported the commonly expressed need of non-church people to have a funeral that was personal in nature, with a minimum of platitudes, and also a personal eulogy that was well prepared, and substantial in its coverage of the life of the person who had died. There was a strong antipathy to mistakes which people had experienced in funeral services, such as factual errors: the deceased being called by the wrong name, or a mispronounced name, as was characteristic of many under-prepared and ritualistic funeral ceremonies provided by the churches.[14] The public also required that music, quotations and individual tributes be appropriate to the deceased person. (Clergy were then induced to compete with these standards and were thus led to provide more personalised ceremonies.[9])

Issues with fees

[edit]The new funeral celebrants needed to establish working relationships with the funeral directors, whose role was to collect, prepare and store the bodies of the deceased. Funeral directors were then (1970s and 1980s) mostly smaller family owned firms. Funeral directors John and Rob Allison of John Allison Monkhouse (Melbourne, Victoria) were particularly supportive of funeral celebrants. So was the active idealist Des Tobin, general manager of Tobin Brothers Funeral Parlours of Melbourne.[15] The fee that funeral directors had customarily paid to clergy was not a fee for service but merely an "offering", since the general presumption was that the client was a churchgoer, who had donated to the upkeep of the clergy all his or her life.[16]

Funeral celebrants argued that those who required a personally prepared service, which required many extra hours of preparation, should pay more. Rob Allison agreed, and a two-tiered structure of fees was established. The funeral directors argued that the fee should be fixed so they could quote costs clearly to the client. The resulting two-tiered fee acknowledged that civil funeral celebrants had no other sources of income such as clergy had. However, this happened only in Victoria. Funeral directors in other states of Australia refused to pay celebrants any more than they had decided to pay the clergy. This led predictably to unsatisfactory standards and uninspiring funeral services.[4]: 147–192

Training and education of celebrants

[edit]Training

[edit]

It also became clear, as funeral celebrancy became an organised profession, that it was not appropriate for funeral celebrants to learn how to carry out the work by learning from one's mistakes and experience while "on the job". Celebrants observed that mistakes made in funeral ceremonies could leave lifelong psychological scars. It was clear that skills such as creative writing and public speaking, a knowledge of suitable poetic, literary, symbolic and musical resources, an awareness of punctuality and time, appropriate dress and similar were essential. It was clear that a formal educational and training process was required.[4]: 148–150

Education

[edit]Experienced celebrants maintained it was crucial for trainee celebrants to achieve an understanding of the "grief process" and how it impacted on their work. The Australian lecture tour of a renowned scholar in this area, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, organised by funeral celebrant Diane Storey, received wide media publicity and was credited with changing social attitudes to death and dying.[4]: 153 Training, in the informal sense, began by constant reflective interaction among the original celebrants who all knew each other. Later on when more funeral celebrants were attracted to the vocation, programs of seminars were set up by celebrants Beverley Silvius, Diane Storey and Brian and Tina McInerney. This body of learning was later incorporated into the courses more formally prepared by the College of Celebrancy in 1995.[4]: 226 & 260

Celebrant professionalism

[edit]It was agreed that adequate training of celebrants must leave them capable of providing the standards the general public expected such as full personal interaction and cooperation with the family, careful preparation of a historical and personal eulogy, attentive choosing of readings (poetry and prose), music, choreography (processionals and recessionals), symbolism, and an appropriate setting and place for the ceremony. Another essential was that celebrants should check the eulogy and the ceremony with a member of the family, so that harmful mistakes were avoided. In short, funeral ceremonies were viewed as a serious responsibility which should be prepared with efficiency and attention to detail, requiring an attitude of genuineness, empathy and compassion.[9] The high ideals of the original celebrants and the ones who slowly joined their ranks changed the nature of the funeral ceremony scene in Melbourne and Victoria. They professed to offer the best and most personal funerals which existed in the Western world. This high standard is well acknowledged by Tony Walter, lecturer and reader in Death and Society at the University of Reading in the UK.[18]

Time magazine report

[edit]International acknowledgement was provided by a comprehensive article in the US news magazine Time (2004) reporting that in the "liberal" cities of Melbourne, Australia, and Auckland, New Zealand, civil celebrants "conduct substantially more than half of the funerals". It reported that before 1973 only clergy funerals were available to the general public in Australia and New Zealand. The article describes celebrant funerals as "intimate and personalised". But it also cited an alternative point of view by atheist sociologist Mira Crouch who stated that celebrant funerals were "mawkish and sentimental".[1]

Australian Institute of Civil Celebrants

[edit]In January 1992 the Australian Institute of Civil Celebrants was able to welcome marriage celebrants, who were increasingly in disagreement with the marriage celebrants associations, which continued to oppose secular funeral celebrants.[4]: 91 Rick Barclay was voted in as president, Dally Messenger III as secretary, and Ken Woodburn as treasurer. These three administered the institute until it became the Australian Federation of Civil Celebrants Inc in January 1994.[16]

Australian states other than Victoria

[edit]Funeral directors in states of Australia other than Victoria still refused to pay celebrants any more than they paid clergy i.e. a low "stipend" or "offering". The results were predictable. With some notable exceptions, very few marriage celebrants were prepared to put the amount of painstaking time and effort into the preparation and checking of funeral ceremonies that was required to reach the Victorian standard. Many funeral directors in these states saw celebrants as a threat to their income and were openly hostile. Several firms declared every member of their staff a celebrant. Others employed an in-house celebrant who was required to perform 13 or 14 funeral ceremonies per week — compelling such employees to resort to one-size-fits-all impersonal ceremonies.[16] A "celebrant funeral" in these contexts became the worst option available. As author and commentator Robert Larkins put it, speaking of one family's experience:

Geoff was not a religious man so there was no minister of religion present, just a celebrant ... Susanne had found the funeral experience to be deeply dissatisfying.[19]

As church attendances declined, funeral directors in New South Wales pushed non-church people into organising "family ceremonies". A few families proved capable of this, but most were not.[16]

Further decline in standards in Australia

[edit]As inflation took hold during the years 1990 to 2009 the value of money declined. Funeral directors in Australia, who effectively controlled fees for celebrants, held out against any increases in payments.

The loss of support for celebrants due to the retirements of idealist funeral directors such as Rob and John Allison and Desmond Tobin was keenly felt. The takeover of the small and middle size funeral companies by the multinational company Invocare Limited,[20] meant there was little interest in any celebrant standards of ceremony. Larkins lists five pages of funeral homes purchased by Invocare Limited[21] including such names as Simplicity Funerals, White Lady Funerals, Tobin Brothers Funerals and Le Pine Funerals. All these smaller firms kept their original names, thus misleading the public as to ownership.[22] Notwithstanding the above, a core group of funeral celebrants throughout Australia still provide the public with funeral ceremonies in accordance with the original ideals.[23]

Funeral celebrants in NZ, UK and US

[edit]In the late 1970s, New Zealand followed Australia in establishing funeral celebrants and has had an untroubled history.[1] The Humanist Society of England and Scotland, after many visits to Australia in the 1980s, established a wide network of quality funeral celebrants characterised by a strong non-religious stance.[24]

The Institute of Civil Funerals (IoCF), on the other hand, has a more family-centred approach and its members include as little or as much religion as requested.

The IoCF is the oldest funeral celebrant organisation in the UK (founded 2004) and the only one with professional institute status. Membership of IoCF indicates that a celebrant has studied and achieved the highest accredited qualification currently awarded - the Level 3 Diploma in funeral celebrancy. Training for this qualification is available only through Civil Ceremonies Ltd, rated outstanding by OFSTED,[25] and through Green Fuse and signifies that a celebrant has had professional training and has passed rigorous assessment.

Others in the UK have set themselves up as civil funeral celebrants based on the Australian/Victorian model. They are gaining wide acceptance particularly funeral celebrants trained by the United Kingdom Society of Celebrants.

Celebrant training in the UK has not really progressed over recent years, with some core providers still using the original Australian training model along with outdated and religious based terminologies.

New training organisations are emerging that bring a new outlook on celebrant training producing a new generation of celebrants.

The Celebrant Foundation and Institute in the US, established by graduates of the Australian-based International College of Celebrancy in 2003, has emerged as the leading organisation in training and educating civil celebrants in the US. Originally a force for secular wedding and naming ceremonies, since 2009 some civil celebrants in the US have become more involved in high standard funeral ceremonies.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Williams, Daniel (6 September 2004). "Funerals Are Us". Time. No. 35. pp. 56–7.

- ^ Wilson, Sherryl (2018). CANZ from the beginning : a history of the Celebrants' Association of New Zealand. Wellington, NZ: The Celebrants Association of New Zealand. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-473-44837-0.

- ^ "Start a second career or change jobs, Become a Celebrant". Celebrant Institute. Celebrant Foundation and Institute USA. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Messenger, Dally (2012), Murphy's Law and the Pursuit of Happiness: A History of the Civil Celebrant Movement, Spectrum Publications, Melbourne (Australia), ISBN 978-0-86786-169-3 pp148-192

- ^ Note: For the US, see Celebrant Foundation and Institute

- ^ Note: For the UK, see Humanist celebrant and Humanists UK

- ^ Note: for various other countries, see Dally Messenger III#Civil celebrancy in the United Kingdom etc.

- ^ "Celebrant USA Foundation Launches in Montclair". The Montclair Times. 13 June 2002.

- ^ a b c d e f Messenger, Dally, Ceremonies and Celebrations, Hachette Livre, Melbourne, 2000, ISBN 978 0 7336 2317 2

- ^ "Cultural diversity". 1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2008. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 7 February 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ "Funeral Celebrants Association | Join or Find Your Celebrant Today". www.funeralcelebrants.org.au. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Adams, Pamela, "Music suggestions for Funeral Ceremonies", Celebrations, Australian Federation of Civil Celebrants Inc 2009

- ^ Harrington, Tony (18 January 1980). "Business grows for civil matchers and dispatchers". The Town Crier. Melbourne-Mornington Peninsula.

- ^ Marinos, Sarah, Prepare Yourself to say Goodbye, Family Circle, June 1997 pp40-41

- ^ Messenger, Dally, "Victorian Celebrants Lead the World", The Australian Funeral Director, December 1994

- ^ a b c d Messenger III, Dally (26 September 2005). "Best Practice Funerals; Keynote Address". funeralsbycelebrants.com.au. International College of Celebrancy. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Lahey, John: Cherished but not Cradled, Australian Funeral Director, September 1986, p.6

- ^ Walter, Tony, "Secular Funerals or Life-Centred Funerals?" in, Funerals and How to Improve Them, Hodder and Staughton, London, 1990, ISBN 978-0340531259, pp. 217-231

- ^ Larkins, Robert, Funeral Rights: What the Australian 'Death-Care' Industry Doesn't Want You to Know, Penguin Australia, Camberwell Victoria, 2007, ISBN 978 0 67007108 1 p.ix

- ^ Henly, Susan, "Death of a Salesman", The Age. Melbourne, Extra section p.18, 28 August 2005

- ^ McNicol, D. D., "Lifting the Lid on the Funeral Industry", The Australian, Summer Living Section p.12, 2 January 2006

- ^ Larkins, Robert, Funeral Rights: What the Australian 'Death-Care' Industry Doesn't Want You to Know, Penguin Australia, Camberwell Victoria, 2007, ISBN 978 0 67007108 1 pp.231-235

- ^ "Quality Funeral Celebrants on hourly rates".

- ^ Meaningful non-religious ceremonies just for you, British Humanist Association, Retrieved 24 February 2015

- ^ "Civil Ceremonies Ltd assessed as Outstanding". OFSTED. April 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Machelor, Patty, http://www.celebrantinstitute.org/media/Arizona%20Star%20Story/Arizona%20Star%20Story.htm, Arizona Daily Star, 30 December 2012

KSF

KSF