Civil rights movement (1865–1896)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 50 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 50 min

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

The civil rights movement (1865–1896) aimed to eliminate racial discrimination against African Americans, improve their educational and employment opportunities, and establish their electoral power, just after the abolition of slavery in the United States. The period from 1865 to 1895 saw a tremendous change in the fortunes of the Black community following the elimination of slavery in the South.

Immediately after the American Civil War, the federal government launched a program known as Reconstruction which aimed to rebuild the states of the former Confederacy. The federal programs also provided aid to the former slaves and attempted to integrate them into society as citizens. Both during and after this period, Black people gained a substantial amount of political power and many of them were able to move from abject poverty to land ownership. At the same time resentment of these gains by many whites resulted in an unprecedented campaign of violence which was waged by local chapters of the Ku Klux Klan, and in the 1870s it was waged by paramilitary groups like the Red Shirts and White League.

In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537,[a] a landmark case upholding "separate but equal" racial segregation as constitutional. It was a very significant setback for civil rights, as the legal, social, and political status of the Black population reached a nadir. From 1890 to 1908, beginning with Mississippi, southern states passed new constitutions and laws disenfranchising most Black people and excluding them from the political system, a status that was maintained in many cases into the 1960s.

Much of the early reform movement during this era was spearheaded by the Radical Republicans, a faction of the Republican Party. By the end of the 19th century, with disenfranchisement in progress to exclude Black people from the political system altogether, the so-called lily-white movement also worked to substantially weaken the power of remaining Black people in the party. The most important civil rights leaders of this period were Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) and Booker T. Washington (1856–1915).

Reconstruction

[edit]

Reconstruction lasted from Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863 to the Compromise of 1877.[1][2]

The major issues faced by President Abraham Lincoln were the status of the ex-slaves (called "Freedmen"), the loyalty and civil rights of ex-rebels, the status of the 11 ex-Confederate states, the powers of the federal government needed to prevent a future civil war, and the extent of Congress's versus the president's power.

The severe threats of starvation and displacement of the unemployed Freedmen were met by the first major federal relief agency, the Freedmen's Bureau, operated by the Army.[3]

Three "Reconstruction Amendments" were passed to expand civil rights for Black Americans: the Thirteenth Amendment outlawed slavery; the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed equal rights for all and citizenship for Black people; the Fifteenth Amendment prevented race from being used to disfranchise men.

Of more immediate usefulness than the constitutional amendments, were laws passed by Congress to allow the federal government, through the new Justice Department and through the federal courts to enforce the new civil rights Even if the state governments ignored the problem. These included the Enforcement Acts of 1870–71 and the Civil Rights Act of 1875.[4][5]

Ex-Confederates remained in control of most Southern states for more than two years, but that changed when the Radical Republicans gained control of Congress in the 1866 elections. President Andrew Johnson, who sought easy terms for reunions with ex-rebels, was virtually powerless; he escaped by one vote removal through impeachment. Congress enfranchised Black men and temporarily suspended many ex-Confederate leaders of the right to hold office. New Republican governments came to power based on a coalition of Freedmen together with Carpetbaggers (new arrivals from the North), and Scalawags (native white Southerners). They were backed by the US Army. Opponents said they were corrupt and violated the rights of whites. State by state they lost power to a conservative-Democratic coalition, which gained control by violence and fraud of the entire South by 1877. In response to Radical Reconstruction, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) emerged in 1867 as a white-supremacist organization opposed to Black civil rights and Republican rule. President Ulysses Grant's vigorous enforcement of the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1870 shut down the Klan, and it disbanded. But from 1868 elections in many southern states were increasingly surrounded by violence to suppress Black voting. Rifle clubs had thousands of members. In 1874, paramilitary groups, such as the White League and Red Shirts emerged that worked openly to use intimidation and violence to suppress Black voting and disrupt the Republican Party to regain white political power in states across the South. Rable described them as the "military arm of the Democratic Party."[6]

Reconstruction ended after the disputed 1876 election between Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes and Democratic candidate Samuel J. Tilden. With a compromise Hayes won the White House, the federal government withdrew its troops from the South, abandoning the freedmen to white conservative Democrats, who regained power in state governments.[7]

Kansas exodus

[edit]Following the end of Reconstruction, many Black people feared the Ku Klux Klan, the White League and the Jim Crow laws which continued to make them second-class citizens.[8] Motivated by important figures such as Benjamin "Pap" Singleton, as many as forty thousand Exodusters left the South to settle in Kansas, Oklahoma and Colorado.[9] This was the first general migration of Black people following the Civil War.[10] In the 1880s, Black people bought more than 20,000 acres (81 km2) of land in Kansas, and several of the settlements made during this time (e.g. Nicodemus, Kansas, which was founded in 1877) still exist today. Many Black people left the South with the belief that they were receiving free passage to Kansas, only to be stranded in St. Louis, Missouri. Black churches in St. Louis, together with Eastern philanthropists, formed the Colored Relief Board and the Kansas Freedmen's Aid Society to help those stranded in St. Louis to reach Kansas.[8]

One particular group was the Kansas Fever Exodus, which consisted of six thousand Black people who moved from Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas to Kansas.[11] Many in Louisiana were inspired to leave the state when the 1879 Louisiana Constitutional Convention decided that voting rights were a matter for the state, not federal, government, thereby clearing the way for the disenfranchisement of Louisiana's Black population.[8]

The exodus was not universally praised by African Americans; indeed, Frederick Douglass was a critic.[12] Douglass felt that the movement was ill-timed and poorly organized.[13]

Political organization

[edit]

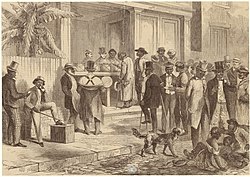

Black men across the South obtained the right to vote in 1867, and joined the Republican Party. The typical organization was through the Union League, a secret society organized locally but promoted by the national Republican Party. Eric Foner reports:

- By the end of 1867 it seemed that virtually every Black voter in the South had enrolled in the Union League, the Loyal League, or some equivalent local political organization. Meetings were generally held in a Black church or school.[14]

The Union Leagues promoted militia-like organizations in which the Black people banded together to protect themselves from being picked off one-by-one by harassers. Members were not allowed to vote the Democratic ticket.[15] The Union Leagues and similar groups came under violent assault from the KKK after 1869, and largely collapsed. Later efforts to revive the Union League failed.[16]

Black ministers provided much of the Black political leadership, together with newcomers who had been free Black people in the North before the Civil War. Many cities had Black newspapers that explained the issues and rallied the community.[17]

Factionalism

[edit]In state after state across the South, a polarization emerged inside the Republican Party, with the Black people and their carpetbagger allies forming the Black-and-tan faction, which faced the all-white "lily-white" faction of local white scalawag Republicans.[18] (The terms for the factions became common after 1888, a decade after the end of Reconstruction.)[19] The Black people comprised the majority of Republican voters, but got a small slice of the patronage. They demanded more. Hahn explains the steps they took:

- Black assertiveness....looked toward local political power and independence and began to construct a new political identity. Black laborers called white party leaders to account. They moved to control the county and district party machinery. They rejected white office-seekers and substituted Black ones. They nominated all-Black electoral slates.[20]

The Black-and-tan element usually won the factional battle, but as scalawags lost intra-party battles, many started voting for the conservative or Democratic tickets. The Republican Party became "Blacker and Blacker over time", as it lost white voters.[21] The most dramatic episode was the Brooks–Baxter War in Arkansas in 1874.[22] Michael Les Benedict says, "Every modern history of Reconstruction stresses its [factionalism] contribution to the collapse of southern Republicanism."[23] In terms of racial issues, Sarah Woolfolk Wiggins argues:

- White Republicans as well as Democrats solicited Black votes but reluctantly rewarded Black people with nominations for office only when necessary, even then reserving the more choice positions for whites. The results were predictable: these half-a-loaf gestures satisfied neither Black nor white Republicans. The fatal weakness of the Republican Party in Alabama, as elsewhere in the South, was its inability to create a biracial political party. And while in power even briefly, they failed to protect their members from Democratic terror. Alabama Republicans were forever on the defensive, verbally and physically.[24]

Populism

[edit]In 1894, a wave of agrarian unrest swept through the cotton and tobacco regions of the South. The most dramatic impact came in North Carolina, where the poor white farmers who comprised the Populist party formed a working coalition with the Republican Party, then largely controlled by Black people in the low country, and poor whites in the mountain districts. They took control of the state legislature in both 1894 and 1896, and the governorship in 1896. The state legislature lowered property requirements, expanding the franchise for the white majority in the state as well as for Black people. In 1895, the Legislature rewarded its Black allies with patronage, naming 300 Black magistrates in eastern districts, as well as deputy sheriffs and city policemen. They also received some federal patronage from the coalition congressman, and state patronage from the governor.[25]

Determined to regain power, white Democrats mounted a campaign based on white supremacy and fears about miscegenation. The white supremacy election campaign of 1898 was successful, and Democrats regained control of the state legislature. But Wilmington, the largest city and one with a Black majority, elected a biracial Fusionist government, with a white mayor and two-thirds of the city council being whites. Democrats had already planned to overthrow the government if they lost the election here and proceeded with the Wilmington Insurrection of 1898. The Democrats ran Black people and Fusionist officials out of town, attacking the only Black newspaper in the state; white mobs attacked Black areas of the city, killing and injuring many, and destroying homes and businesses built up since the war.[26] An estimated 2100 Black people left the city permanently, leaving it a white-majority city. There were no further insurgencies in any Southern states that had a successful Black-Populist coalition at the state level. In 1899, the white Democratic-dominated North Carolina legislature passed a suffrage amendment disenfranchising most Black people. They would largely not recover the power to vote until after passage of the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Economic and social conditions

[edit]The great majority of Black people in this period were farmers. Among them were four main groups, three of which worked for white landowners: tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and agricultural laborers.[27][28][29]

The fourth group were the Black people who owned their own farms, and were to some degree independent of white economic control.[30]

Urban elements

[edit]The South had relatively few cities of any size in 1860, but during the war, and afterward, refugees both Black and white flooded in from rural areas. The growing Black population produced a leadership class of ministers, professionals, and businessmen.[31][32] These leaders typically made civil rights a high priority. Of course, great majority of Black people in urban America were unskilled or low skilled blue-collar workers.[33] Historian August Meier reports:

- From the late 1880s there was a remarkable development of Negro business – banks and insurance companies, undertakers and retail stores.... It occurred at a time when Negro barbers, tailors caterers, trainmen, Black peoplemiths, and other artisans were losing their white customers. Depending upon the Negro market, the promoters of the new enterprises naturally upheld the spirit of racial self-help and solidarity.[34][35]

Memphis

[edit]

During the war thousands of slaves escaped from rural plantations to Union lines, and the Army established a contraband camp next to Memphis, Tennessee. By 1865, there were 20,000 Black people in the city, a sevenfold increase from the 3,000 before the war.[36] The presence of Black Union soldiers was resented by Irish Catholics in the city, who competed with Black people for unskilled labor jobs. In 1866, there was a major riot with whites attacking Black people. Forty-five Black people were killed, and nearly twice as many wounded; much of their makeshift housing was destroyed.[37] By 1870, the Black population was 15,000 in a city total of 40,226.[36]

Robert Reed Church (1839–1912), a freedman, was the South's first Black millionaire.[38] He made his wealth from speculation in city real estate, much of it after Memphis became depopulated after the yellow fever epidemics. He founded the city's first Black-owned bank, Solvent Savings Bank, ensuring that the Black community could get loans to establish businesses. He was deeply involved in local and national Republican politics and directed patronage to the Black community. His son became a major politician in Memphis. He was a leader of Black society and a benefactor in numerous causes. Because of the drop in city population, Black people gained other opportunities. They were hired to the police force as patrolmen and retained positions in it until 1895, when imposed segregation forced them out.[39]

Atlanta

[edit]Atlanta, Georgia had been devastated in the war, but as a major railroad center it rebuilt rapidly afterwards, attracting many rural migrants. From 1860 to 1870 Fulton County (of which Atlanta was the county seat) more than doubled in population, from 14,000 to 33,000. In a pattern seen across the South, many freedmen moved from plantations to towns or cities for work and to gather in communities of their own. Fulton County went from 20.5% Black in 1860 to 45.7% Black in 1870.[40] Atlanta quickly became a leading national center of Black education. The faculty and students provided a supportive environment for civil rights discussions and activism. Atlanta University was established in 1865. The forerunner of Morehouse College opened in 1867, Clark University opened in 1869. What is now Spelman College opened in 1881, and Morris Brown College in 1885. This would be one of several factors aiding the establishment of one of the nation's oldest and best-established African American elite in Atlanta.

Philadelphia

[edit]Philadelphia, Pennsylvania was one of the largest cities north of the Mason–Dixon line, and attracted many free Black people before the Civil War. They generally lived in the Southwark and Moyamensing neighborhoods. By the 1890s, the neighborhoods had a negative reputation in terms of crime, poverty, and mortality.[41] W.E.B. Du Bois, in his pioneering sociological study The Philadelphia Negro (1899), undermined the stereotypes with experimental evidence. He shaped his approach to segregation and its negative impact on Black lives and reputations. The results led Du Bois to realize that racial integration was the key to democratic equality in American cities.[42]

Education

[edit]The African-American community engaged in a long-term struggle for quality public schools. Historian Hilary Green says it "was not merely a fight for access to literacy and education, but one for freedom, citizenship, and a new postwar social order."[43] The Black community and its white supporters in the North emphasized the critical role of education is the foundation for establishing equality in civil rights.[44] Anti-literacy laws for both free and enslaved Black people had been in force in many southern states since the 1830s,[45] The widespread illiteracy made it urgent that high on the African-American agenda was creating new schooling opportunities, including both private schools and public schools for Black children funded by state taxes. The states did pass suitable laws during Reconstruction, but the implementation was weak in most rural areas, and with uneven results in urban areas. After Reconstruction ended the tax money was limited, but local Black people and national religious groups and philanthropists helped out.

Integrated public schools meant local white teachers in charge, and they were not trusted. The Black leadership generally supported segregated all-Black schools.[46][47] The Black community wanted Black principals and teachers, or (in private schools) highly supportive whites sponsored by northern churches. Public schools were segregated throughout the South during Reconstruction and afterward into the 1950s. New Orleans was a partial exception: its schools were usually integrated during Reconstruction.[48]

In the era of Reconstruction, the Freedmen's Bureau opened 1000 schools across the South for Black children using federal funds. Enrollments were high and enthusiastic. Overall, the Bureau spent $5 million to set up schools for Black people and by the end of 1865, more than 90,000 Freedmen were enrolled as students in public schools. The school curriculum resembled that of schools in the north.[49] By the end of Reconstruction, however, state funding for Black schools was minimal, and facilities were quite poor.[50]

Many Freedman Bureau teachers were well-educated Yankee women motivated by religion and abolitionism. Half the teachers were southern whites; one-third were Black people, and one-sixth were northern whites.[51] Black men slightly outnumbered Black women. The salary was the strongest motivation except for the northerners, who were typically funded by northern organizations and had a humanitarian motivation. As a group, only the Black cohort showed a commitment to racial equality; they were the ones most likely to remain teachers.[52]

Secondary and collegiate education

[edit]Almost all colleges in the South were strictly segregated; a handful of northern colleges accepted Black students. Private schools were established across the South by churches, and especially by northern denominations, to provide education after elementary schooling. They focused on secondary level (high school) work and provided a small amount of collegiate work.[53] Tuition was minimal, so national and local churches often supported the colleges financially, and also subsidized some teachers. The largest dedicated organization was the American Missionary Association, chiefly sponsored by the Congregational churches of New England.[54]

In 1900, Northern churches or organizations they sponsored operated 247 schools for Black people across the South, with a budget of about $1 million. They employed 1600 teachers and taught 46,000 students.[54][55] At the collegiate level the most prominent private schools were Fisk University in Nashville, Atlanta University, and Hampton Institute in Virginia. A handful were founded in northern states. Howard University was a federal school based in Washington.

In 1890, Congress expanded the land-grant plan to include federal support for state-sponsored colleges across the South. It required southern states with segregated systems to establish Black colleges as land-grant institutions so that all students would have an opportunity to study at such places. Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute was of national importance because it set the standards for industrial education.[56] Of even greater influence was Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers, founded in 1881 by the state of Alabama and led by Hampton alumnus Booker T. Washington until his death in 1915. Elsewhere, in 1900 there were few Black students enrolled in college-level work.[57]

Only 22 Black people graduated from college before the Civil War. Oberlin College in Ohio was a pioneer; it graduated its first Black student in 1844.[58] The number of Black graduates rose rapidly: 44 graduated in the 1860s; 313 in the 1870s; 738 in the 1880s; 1126 in the 1890s; and 1613 in the decade 1900–1909. They became professionals; 54% became teachers; 20% became clergyman; others were physicians, lawyers or editors. They averaged about $15,000 in wealth. Many provided intellectual and organizational support for civic projects, especially civil rights activities at the local level.[59] While the colleges and academies were generally coeducational, historians until recently largely ignored the role of women as students and teachers.[60]

Funding and philanthropy

[edit]Funding for education for Black people in the South came from multiple sources. From 1860 to 1910, religious denominations and philanthropies contributed about $55 million. Black people themselves through their churches, contributed over $22 million. The southern states spent about $170 million in tax dollars on Black schools, and about six times that amount for white schools.[61]

Much philanthropy from rich Northerners focused on the education of Black people in the South. By far the largest early funding came from the Peabody Education Fund. The money was donated by George Peabody, originally of Massachusetts, who made a fortune in finance in Baltimore and London. He gave $3.5 million to "encourage the intellectual, moral, and industrial education of the destitute children of the Southern States."[61][62]

The John F. Slater Fund for the Education of Freedmen was created in 1882 with $1.5 million for "Uplifting the legally emancipated population of the Southern states and their posterity."[63] After 1900, even larger sums came from Rockefeller's General Education Board, from Andrew Carnegie and from the Rosenwald Foundation.[64]

By 1900, the Black population in the United States had reached 8.8 million; it was based overwhelmingly in the rural South. The school-age population was 3 million; half of them were in attendance. They were taught by 28,600 teachers, the vast majority of whom were Black. Schooling (for both whites and Black people) was geared to teaching the three R's to younger children. There were only 86 high schools for Black people in the entire South, plus 6 in the North. These 92 schools had 161 male teachers, and 111 female teachers; they taught 5200 students in the high school grades. In 1900, there were only 646 Black people who graduated from high school.[65]

Religion

[edit]Black churches played a powerful role in the civil rights movement. They were the core community group around which Black Republicans organize their partisanship.[66][67] The great majority of the Black Baptist and Methodist churches rapidly became independent of the primarily white national or regional denominations after 1865. Black Baptist congregations set up their own associations and conventions.[68] Their ministers became leading political spokesman for their congregations.[69] Black women found their own space and church-sponsored organizations, ranging from choirs to missionary projects, to church schools and Sunday schools.[70]

In San Francisco there were three Black churches in the early 1860s. They all sought to represent the interests of the Black community, provided spiritual leadership and rituals, organized help for the needy, and fought against attempts to deny Black people their civil rights.[71] The San Francisco Black churches had decisive support from the local Republican Party. In the 1850s, the Democrats controlled the state and enacted anti-Black legislation. Even though Black slavery had never existed in California, the laws were harsh. The Republican Party came to power in the early 1860s, and rejected exclusion and legislative racism. Republican leaders joined Black activists to win the legal rights, especially in terms of the right to vote, the right to attend public schools, equal treatment in public transportation, and equal access to the court system.[72]

Black Americans, once freed from slavery, were very active in forming their own churches, most of them Baptist or Methodist, and giving their ministers both moral and political leadership roles. In a process of self-segregation, practically all Black people left white churches so that few racially integrated congregations remained (apart from some Catholic churches in Louisiana). Four main organizations competed with each other across the South to form new Methodist churches composed of freedmen. They were the African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, founded in New York City; the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (which was sponsored by the white Methodist Episcopal Church, South), and the well-funded Methodist Episcopal Church (Northern white Methodists).[73][74] By 1871, the Northern Methodists had 88,000 Black members in the South, and had opened numerous schools for them.[75]

The Black people during Reconstruction Era were politically the core element of the Republican Party, and the ministers played a powerful political role. Their ministers could be more outspoken since they did not primarily depend on white support, in contrast to teachers, politicians, businessmen, and tenant farmers.[76] Acting on the principle expounded by Charles H. Pearce, an AME minister in Florida: "A man in this State cannot do his whole duty as a minister except he looks out for the political interests of his people," over 100 Black ministers were elected to state legislatures during Reconstruction. Several served in Congress and one, Hiram Revels, in the U.S. Senate.[77]

Methodists

[edit]

The most well organized and active of the Black churches was the African Methodist Episcopal church (AME). In Georgia, AME Bishop Henry McNeal Turner (1834–1915) became a leading spokesman for justice and equality. He served as a pastor, writer, newspaper editor, debater, politician, the chaplain of the Army, and a key leader of emerging Black Methodist organization in Georgia and the Southeast. In 1863, during the Civil War, Turner was appointed as the first Black chaplain in the United States Colored Troops. Afterward, he was appointed to the Freedmen's Bureau in Georgia. He settled in Macon, Georgia, and was elected to the state legislature in 1868 during Reconstruction. He planted many AME churches in Georgia. In 1880, he was elected as the first southern bishop of the AME Church after a fierce battle within the denomination. He fought Jim Crow laws.[78]

Turner was the leader of Black nationalism and promoted emigration of Black people to Africa. He believed in separation of the races. He started a back-to-Africa movement in support of the Black American colony in Liberia.[79] Turner built Black pride by proclaiming "God is a Negro."[80][81]

There was a second all-Black Methodist Church, the smaller African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ). AMEZ remained smaller than AME because some of its ministers lacked the authority to perform marriages, and many of its ministers avoided political roles. Its finances were weak, and in general its leadership was not as strong as AME. However it was the leader among all Protestant denominations in ordaining women and giving them powerful roles.[82] One influential leader was bishop James Walker Hood (1831–1918) of North Carolina. He not only created and fostered his network of AMEZ churches in North Carolina, but he also was the grand master for the entire South of the Prince Hall Masonic Lodge, a secular organization that strengthen the political and economic forces inside the Black community.[83]

In addition to all-Black churches, many Black Methodists were associated with the Northern Methodist Church. Others were associated with the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church CME; CME was an organ of the white Southern Methodist Church.[84] In general, the most politically active Black ministers affiliated with AME.[85]

Baptists

[edit]Black Baptists broke from the white churches and formed independent operations across the South,[86] rapidly forming state and regional associations.[87] Unlike the Methodists, who had a hierarchical structure led by bishops, the Baptist churches were largely independent of each other, although they pooled resources for missionary activities, especially missions in Africa.[88] The Baptist women worked hard to carve out a partially independent sphere inside the denomination.[70][89]

Urban churches

[edit]The great majority of Black people lived in rural areas where services were held in small makeshift buildings. In the cities Black churches were more visible. Besides their regular religious services, the urban churches had numerous other activities, such as scheduled prayer meetings, missionary societies, women's clubs, youth groups, public lectures, and musical concerts. Regularly scheduled revivals operated over a period of weeks reaching large, appreciative and noisy crowds.[90]

Charitable activities abounded concerning the care of the sick and needy. The larger churches had a systematic education program, besides the Sunday schools, and Bible study groups. They held literacy classes to enable older members to read the Bible. Private Black colleges, such as Fisk in Nashville, often began in the basement of the churches. Church supported the struggling small business community.[90]

Most important was the political role. Churches hosted protest meetings, rallies, and Republican party conventions. Prominent laymen and ministers negotiated political deals, and often ran for office until disfranchisement took effect in the 1890s. In the 1880s, the prohibition of liquor was a major political concern that allowed for collaboration with like-minded white Protestants. In every case, the pastor was the dominant decision-maker. His salary ranged from $400 a year to upwards of $1500, plus housing – at a time when 50 cents a day was good pay for unskilled physical labor.[90]

Increasingly the Methodists reached out to college or seminary graduates for their ministers, but most Baptists felt that education was a negative factor that undercut the intense religiosity and oratorical skills they demanded of their ministers.[90]

After 1910, as Black people migrated to major cities in both the North and the South, there emerged the pattern of a few very large churches with thousands of members and a paid staff, headed by an influential preacher. At the same time there were many "storefront" churches with a few dozen members.[91]

Religious interpretation of history

[edit]Deeply religious Southerners saw the hand of God in history, which demonstrated His wrath at their sinfulness, or His rewards for their suffering. Historian Wilson Fallin has examined the sermons of white and Black Baptist preachers after the War. Southern white preachers said:

God had chastised them and given them a special mission – to maintain orthodoxy, strict biblicism, personal piety, and traditional race relations. Slavery, they insisted, had not been sinful. Rather, emancipation was a historical tragedy and the end of Reconstruction was a clear sign of God's favor.

In sharp contrast, Black preachers interpreted the Civil War as:

God's gift of freedom. They appreciated opportunities to exercise their independence, to worship in their own way, to affirm their worth and dignity, and to proclaim the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. Most of all, they could form their own churches, associations, and conventions. These institutions offered self-help and Racial uplift, and provided places where the gospel of liberation could be proclaimed. As a result, Black preachers continued to insist that God would protect and help him; God would be their rock in a stormy land.[92]

Deteriorating status

[edit]After 1880, legal conditions worsened for Black people, and they were almost powerless to resist.[93] The Northern allies in the Republican Party made an effort in 1890 to stop the deteriorating legal conditions by congressional legislation, but failed.[94] Every southern state passed codes requiring segregation in most public places. These persisted until 1964, when they were repealed by Congress. They are known as Jim Crow laws.[95] The Southern states In the 1890–1905 period systematically reduced the number of Black people allowed to vote to about 2% through restrictions that skirted the 15th amendment, because they did not explicitly mention race. These restrictions included literacy requirements, voter-registration laws, and poll taxes. The U.S. Supreme Court in 1896 ruled in favor of Jim Crow in the case of Plessy vs. Ferguson, declaring that "separate but equal" facilities for Black people were legal under the 14th Amendment.[96]

Jim Crow laws and segregation

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

Typically in the Black Codes across the seven states of the lower South in 1866 intermarriage was illegal. The new Republican legislatures in six states repealed the restrictive laws. After the Democrats returned to power, the restriction was reimposed. Not until 1967 did the United States Supreme Court, in Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1,[b] rule that all provisions like it in 16 states were unconstitutional. A major concern in the 1860s was how to draw the line between Black and white in a society in which white men and Black slave women had fathered numerous children. On the one hand, a person's reputation, as Black or white, was usually decisive. On the other hand, most laws used a "one drop of blood" criteria to the effect that one Black ancestor legally put a person in the Black category.[97] Legal segregation was imposed only in schooling, and marriage, but that changed in 1880s when new Jim Crow laws mandated the physical separation of the races in public places.[98]

From 1890 to 1908, southern states effectively disfranchised most Black voters and many poor whites by making voter registration more difficult through poll taxes, literacy tests, and other arbitrary devices. They passed segregation laws and imposed second-class status on Black people in a system known as Jim Crow that lasted until the civil rights movement.[99]

Political activities on behalf of equality often centered around transportation issues, such as segregation on streetcars and railroads.[100] Beginning in the 1850s, lawsuits were filed against segregated streetcars and railroads in both the North and South. Some notable plaintiffs included Elizabeth Jennings Graham in New York,[101] Charlotte L. Brown[102] and Mary Ellen Pleasant in San Francisco,[103] Ida B.Wells in Memphis, Tennessee [104] and Robert Fox in Louisville, Kentucky.[105]

Terrorism

[edit]Lynching

[edit]Lynch mob attacks on Black people, especially in the South, rose at the end of the 19th century. The perpetrators were rarely or never arrested or convicted. Nearly 3,500 African Americans and 1,300 whites were lynched in the United States, mostly from 1882 to 1901. The peak year was 1892.[106]

The frequency of lynchings and the episodes that sparked them varied from state to state as functions of local race relations. Lynching was higher in the context of worsening economic conditions for poor rural whites in heavily Black counties, especially the low price of cotton in the 1890s.[107][108] Ida B. Wells (1862–1931) used her newspaper in Memphis Tennessee to attack lynchings; fearful for her life, she fled to the more peaceful precincts of Chicago in 1892 where she continued her one-person crusade.[109] Nationally organized opposition to lynching began with the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. There were 82 lynchings in 1909, and 10 in 1929.[110]

Public images

[edit]In the mainstream national and local media of the late 19th century, "Black people were persistently stereotyped as criminals, savages, or comic figures. They were superstitious, lazy, violent, immoral, the butt of humor, and the source of danger to civilized life."[111] Booker T. Washington, the young college president from Alabama, became famous for his articulate challenges to the extremely negative stereotypes. According to his biographer Robert J. Norrell, Washington:

- challenged the ideological positions of white Southerners on several fronts. His emphasis on Black progress countered the white supremacists insistence on Black degeneracy and criminality. His declaration of affection and loyalty to white Southerners defied the white nationalists believe that all Black people were ethnic enemies. The same time, Washington demonstrated to white Northerners that he and his fellow Black people were loyal, patriotic Americans, the rightful and deserving inheritors of Lincoln's interpretation of democratic values....African-Americans accepted the inherently competitive nature of American society and wanted only a fair chance to prove themselves.[112]

Leadership

[edit]Much of the Black political leadership in this area came from the ministry, and from Union Civil War veterans. The white political leadership featured veterans and lawyers. Ambitious young Black men had a difficult time becoming lawyers, with few exceptions such as James T. Rapier, Aaron Alpeoria Bradley and John Mercer Langston.

The upper class among the Black population was largely mulatto and had been free before the war. During Reconstruction, 19 of the 22 Black members of Congress were mulattoes. These wealthier, mixed-race Black people represented the majority of the leaders in the civil rights movement of the 20th century as well.[113] Hahn reports that the mulatto element held disproportionate power in the Black political community in South Carolina and Louisiana.[114] Many of the leaders, however, were also dark-skinned and former slaves.[115]

Anna J. Cooper

[edit]In 1892, Anna J. Cooper (1858–1964) published A Voice from the South: By A Woman from the South. It led to many speeches where she called for civil rights and woman's rights.[116] A Voice from the South was one of the first articulations of Black feminism. The book advanced a vision of self-determination through education and social uplift for African-American women. Its central thesis was that the educational, moral, and spiritual progress of Black women would improve the general standing of the entire African-American community. She says that the violent natures of men often run counter to the goals of higher education, so it is important to foster more female intellectuals because they will bring more elegance to education.[117] This view was criticized by some as submissive to the 19th-century cult of true womanhood, but others label it as one of the most important arguments for Black feminism in the 19th century.[117] Cooper advanced the view that it was the duty of educated and successful Black women to support their underprivileged peers in achieving their goals. The essays in A Voice from the South also touched on a variety of topics, from racism and the socioeconomic realities of Black families to the administration of the Episcopal Church.

Frederick Douglass

[edit]Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), an escaped slave, was a tireless abolitionist before the war. He was an author, publisher, lecturer and diplomat afterward. His biographer argues:

- The most influential African American of the nineteenth century, Douglass made a career of agitating the American conscience. He spoke and wrote on behalf of a variety of reform causes: women's rights, temperance, peace, land reform, free public education, and the abolition of capital punishment. But he devoted the bulk of his time, immense talent, and boundless energy to ending slavery and gaining equal rights for African Americans. These were the central concerns of his long reform career. Douglass understood that the struggle for emancipation and equality demanded forceful, persistent, and unyielding agitation. And he recognized that African Americans must play a conspicuous role in that struggle. Less than a month before his death, when a young Black man solicited his advice to an African American just starting out in the world, Douglass replied without hesitation: "Agitate! Agitate! Agitate![118]

Key figures

[edit]- Norris Wright Cuney (1846–1898), Galveston, Texas union organizer and chairman of the Republican Party of Texas.

- Timothy Thomas Fortune (1856–1928), journalist, publisher, and founder of the National Afro-American League

- John Mercer Langston (1829–1897), Virginia attorney, U.S. House representative, and president of Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute (now Virginia State University).

- Isaac Myers (1835–1891), trade unionist, founder of Colored National Labor Union

- Robert Smalls (1839–1915), Civil War Union Army hero, U.S. House representative from South Carolina and founder of the Republican Party of South Carolina.

- Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin (1842–1924) editor, organizer, suffragist and founder of the Woman's Era, the first newspaper by and for African-American women

- Sojourner Truth (1797–1883), speaker and activist

- Booker T. Washington (1856–1915), educator, author, and first head of the Tuskegee Institute.

- Ida B. Wells (1862–1931), journalist, newspaper editor, and activist

Timeline

[edit]- 1863 - Emancipation Proclamation frees three of the 4 million slaves, 1863–65.

- 1863 - The first Black to become a college president is Daniel Payne, at Wilberforce University in Ohio, When it comes under the control of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

- 1865 - Congress establishes the Freedman's Bureau.

- 1865 - The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolishes slavery in the handful of remaining Border states.

- 1865 - Shaw Institute was founded in Raleigh, North Carolina, the first historically Black college (HBCU) in the South.

- 1865 - Every southern state passed Black Codes that restricted the Freedmen, who were emancipated but not yet full citizens; the Freedman's Bureau blocks enforcement of these laws.

- 1865 – Atlanta University is founded by the American Missionary Association.

- 1866 - Civil Rights Act of 1866 passed establishing that all persons born in the United States are now citizens.

- 1866 - The first chapter of the Ku Klux Klan is formed in Pulaski, Tennessee, a paramilitary insurgent group, made up of white Confederate Army veterans, to enforce white supremacy.

- 1866 - The U.S. Army regiment of Buffalo Soldiers (African Americans) formed.

- 1866 - Lincoln Institute, later renamed Lincoln University, is founded by returning Black Union soldiers.

- 1867 - Howard University founded in Washington, D.C. Funded by the federal government.

- 1868 - The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution; guarantees citizenship and requires that state governments provide due process and equal protection.

- 1870 - The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prevents the restriction of the vote based on race, color or previous condition of servitude.

- 1870 - Hiram Rhodes Revels becomes the first Black member of the Senate; Joseph Rainey becomes the first Black member of the U.S. House of Representatives.

- 1870- African American Police Constable Wyatt Outlaw of Graham, North Carolina lynched by the Ku Klux Klan.

- 1871 - US Civil Rights Act of 1871 passed, also known as the Klan Act.

- 1872 - P.B.S. Pinchback is sworn in as the first Black Governor of a state of the United States of America.

- 1873 - In the Slaughterhouse Cases the U.S. Supreme Court votes to exclude state laws from being subject to the 14th amendment.

- 1873 - The Colfax and Coushatta Massacres - Murders of Black and white Republicans in Louisiana.

- 1874 - Founding of paramilitary groups that acted as the "military arm of the Democratic Party": the White League in Louisiana and the Red Shirts in Mississippi, and North and South Carolina. They terrorized Black people and Republicans, turning them out of office, killing some, disrupting rallies, and suppressing voting.

- 1875 - Civil Rights Act of 1875 Becomes law.

- 1876 - The Hamburg Massacre occurs when local people riot against African Americans who were trying to celebrate the Fourth of July; African American Police Chief James Cook and five other freemen are killed.

- 1877 - With the Compromise of 1877, federal troops are withdrawn from the South ending Reconstruction.

- 1879 - Exodus of 1879, where thousands of African Americans migrated to Kansas.

- 1880 - In Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303,[c] the Supreme Court rules that Black people could not be excluded from juries.

- 1880s - Segregation of public transportation. Tennessee segregated railroad cars, followed by Florida (1887), Mississippi (1888), Texas (1889), Louisiana (1890), Alabama, Kentucky, Arkansas, and Georgia (1891), South Carolina (1898), North Carolina (1899), Virginia (1900), Maryland (1904), and Oklahoma (1907).

- 1881 - Booker T. Washington opens the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (HBCU) in Tuskegee, Alabama.

- 1883 - The United States Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875 as unconstitutional. The Court declared that the Fourteenth Amendment forbids states, but not citizens, from discriminating.

- 1885 - A biracial populist coalition achieved power in Virginia (briefly).

- 1885 - African-American Samuel David Ferguson was ordained a bishop of the Episcopal church.

- 1886 - Norris Wright Cuney, becomes the chairman of the Texas Republican Party, the most powerful role held by any African American in the South during the 19th century.

- 1890 - Mississippi passes a new constitution that effectively disfranchised most Black people (poll taxes, residency and literacy tests).

- 1892 - Ida B. Wells publishes her pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.

- 1893 - Ida B. Wells, Frederick Douglass, Irvine Garland Penn, and Ferdinand Lee Barnett publish The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not At the World's Columbian Exposition and protest Black exclusion from the Chicago World's Fair.

- 1895 - Booker T. Washington delivered his Atlanta Compromise address at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia.

- 1895 - W. E. B. Du Bois is the first African American to be awarded a Ph.D. by Harvard University.

- 1896 - Wright Cuney is unseated as the chairman of the Texas Republican Party.

- 1896 - In Plessy v. Ferguson[a] the Supreme Court upheld racial segregation of "separate but equal" public facilities.

See also

[edit]- Civil rights movement (1896–1954)

- Civil rights movement (1954–1968)

- African-American culture

- African American founding fathers of the United States

- History of African-American education

- 19th-century African-American civil rights activists

- African-American history

- History of the Southern United States

- Racism against African Americans

- Racism in the United States

- Slavery in the United States

- Reconstruction era

- Lynching in the United States

- Mass racial violence in the United States

- Nadir of American race relations

- Post–civil rights era in African-American history

- Timeline of African-American history

- Timeline of the civil rights movement

- Timeline of racial tension in Omaha, Nebraska

- White backlash#United States

- White nationalism#United States

- White supremacy#United States

References

[edit]- ^ Foner, Eric, A Short History of Reconstruction (1990) online

- ^ Mark Wahlgren Summers, The Ordeal of the Reunion: A New History of Reconstruction (2014).

- ^ Cimbala, Paul A., The Freedmen's Bureau: Reconstructing the American South after the Civil War (2005) includes a brief history and primary documents.

- ^ Kaczorowski, Robert J., "To Begin the Nation Anew: Congress, Citizenship, and Civil Rights after the Civil War." American Historical Review 92.1 (1987): 45–68. in JSTOR

- ^ Cresswell, Stephen, "Enforcing the Enforcement Acts: The Department of Justice in Northern Mississippi, 1870–1890". Journal of Southern History 53#3 (1987): 421–440. in JSTOR

- ^ Rable, George C., But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction (2007).

- ^ Ayers, Edward L., The Promise of the New South: Life After Reconstruction (1992), pp. 3–54.

- ^ a b c Gates, Henry Louis (1999). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Basic Civitas Books. pp. 722. ISBN 978-0-465-00071-5.

- ^ Benjamin "Pap" Singleton, archived from the original on March 11, 2001, retrieved 2007-10-19

- ^ Johnson, Daniel Milo (1981). Black Migration in America: A Social Demographic History. Duke University Press. pp. 51. ISBN 978-0-8223-0449-4.

- ^ Painter, Nell Irvin (1992). Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-393-00951-4.

- ^ Romero, Patricia W. (1968). I Too Am America: Documents from 1619 to the Present. Publishers Agency. pp. 150. ISBN 978-0-87781-206-7.

- ^ Sernett, Milton C. (1997). Bound for the Promised Land: African American Religion and the Great Migration. Duke University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8223-1993-1.

- ^ Eric Foner, "Black Reconstruction Leaders at the Grass Roots" in Leon F. Litwack; August Meier, eds. (1991). Black Leaders of the Nineteenth Century. University of Illinois Press. p. 221. ISBN 9780252062131.

- ^ Hahn, Steven (2003), A Nation under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South, from Slavery to the Great Migration, pp. 174–84.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Michael W. (2000). The Union League Movement in the Deep South: Politics and Agricultural Change During Reconstruction. LSU Press. pp. 2–8, 235, 237. ISBN 9780807126332.

- ^ Abbott, Richard H. (2004), For Free Press and Equal Rights: Republican Newspapers in the Reconstruction South.

- ^ Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's unfinished revolution, 1863–1877 (1988) pp 303-7

- ^ Paul D. Casdorph, "Lily-White Movement," Handbook of Texas Online, accessed March 17, 2016

- ^ Hahn, A Nation under Our Feet (2003), p. 253.

- ^ Hahn, A Nation under Our Feet (2003), p. 254.

- ^ Michael W. Fitzgerald, "Republican Factionalism and Black Empowerment: The Spencer-Warner Controversy and Alabama Reconstruction, 1868–1880". Journal of Southern History 64#3 (1998): 473-494. in JSTOR

- ^ Benedict, Michael Les (2006). Preserving the Constitution: Essays on Politics and the Constitution in the Reconstruction Era. Fordham University Press. p. 247. ISBN 9780823225538.

- ^ Wiggins, Sarah Woolfolk (1977). The Scalawag In Alabama Politics, 1865-1881. University of Alabama Press. p. 134. ISBN 9780817305574.

- ^ Edmunds, Helen G. (1951), The Negro and Fusion Politics in North Carolina, 1894–1901, pp. 97–136.

- ^ Kirshenbaum, Andrea Meryl, "'The Vampire That Hovers Over North Carolina': Gender, White Supremacy, and the Wilmington Race Riot of 1898", Southern Cultures 4#3 (1998), pp. 6–30 online

- ^ Royce, Edward, The Origins of Southern Sharecropping (2010).

- ^ Irwin, James R., and Anthony Patrick O'Brien. "Where Have All the Sharecroppers Gone?: Black Occupations in Postbellum Mississippi." Agricultural History 72#2 (1998): 280-297. in JSTOR

- ^ Ralph Shlomowitz, "'Bound' or 'Free'? Black Labor in Cotton and Sugarcane Farming, 1865–1880." Journal of Southern History 50.4 (1984): 569–596. in JSTOR

- ^ Sharon Ann Holt, "Making freedom pay: Freedpeople working for themselves, North Carolina, 1865–1900." Journal of Southern History 60#2 (1994): 229–262.

- ^ Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution (1988), pp. 396–98.

- ^ Rabinowitz, Howard N., Race Relations in the Urban South, 1865–1890 (1978), pp. 61–96, 240–48.

- ^ James Illingworth, Crescent City Radicals: Black Working People and the Civil War Era in New Orleans. (PhD dissertation, University of California Santa Cruz, 2015) online.

- ^ Meier, August (1963). Negro Thought in America, 1880-1915: Racial Ideologies in the Age of Booker T. Washington. University of Michigan Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0472061181.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ For detailed national report on the numbers of black businessmen and their finances in 1890, see Andrew F. Hilyer, "The Colored American in Business", pp. 13–22, in Proceedings of the National Negro Business League: Its First Meeting Held in Boston, Massachusetts, August 23 and 24, 1900. 1901.

- ^ a b James G. Ryan, "The Memphis Riots of 1866: Terror in a Black Community during Reconstruction", Journal of Negro History (1977) 62#3: 243-257, at JSTOR.

- ^ Art Carden and Christopher J. Coyne, "An Unrighteous Piece of Business: A New Institutional Analysis of the Memphis Riot of 1866", Mercatus Center, George Mason University, July 2010, accessed 1 February 2014

- ^ Kranz, Rachel (2004). African-American Business Leaders and Entrepreneurs. Infobase. pp. 49–51. ISBN 9781438107790.

- ^ Caplinger, Christopher, "Yellow Fever Epidemics", Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture (2010).

- ^ [1] Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine University of West Virginia, Historical Census Browser, 1860 census.

- ^ Roger Lane, William Dorsey's Philadelphia and Ours: On the Past and Future of the Black City in America (1991).

- ^ Martin Bulmer, "W. E. B. Du Bois as a Social Investigator: The Philadelphia Negro, 1899," in Martin Bulmer, Kevin Bales, and Kathryn Kish Sklar, eds. The Social Survey in Historical Perspective, 1880–1940 (1991) pp 170-88.

- ^ Hilary Green, Educational Reconstruction: African American Schools in the Urban South, 1865–1890 (Fordham University Press, 2016), p. 15.

- ^ Foner, Reconstruction, pp. 96–102, 144–46, 322.

- ^ Williams, Heather Andrea, Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom (U of North Carolina Press, 2009).

- ^ Jamerson Reed, Betty (2011). School Segregation in Western North Carolina: A History, 1860s-1970s. McFarland. p. 21. ISBN 9780786487080.

- ^ Painter, Nell Irvin (1992). Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 49–51. ISBN 9780393352511.

- ^ Harlan, Louis R. (1962), "Desegregation in New Orleans Public Schools During Reconstruction." American Historical Review 67#3: 663–675. in JSTOR

- ^ Anderson, James D. (1988). The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1793-3.

- ^ Harlan, Louis R. (1958), Separate and Unequal: Public School Campaigns and Racism in the Southern Seaboard States, 1901–1915, pp. 3–44 online.

- ^ Butchart, Ronald E. (2010). Schooling the Freed People: Teaching, Learning, and the Struggle for Black Freedom, 1861–1876. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3420-6.

- ^ Krowl, Michelle A. (September 2011). "Review of Butchart, Ronald E., Schooling the Freed People: Teaching, Learning, and the Struggle for Black Freedom, 1861–1876". H-SAWH, H-Net Reviews.

- ^ Brooks, F. Erik, and Glenn L. Starks. Historically Black Colleges and Universities: An Encyclopedia (Greenwood, 2011), pp. 11–132, describes the 66 colleges opened by 1900; most are still active today.

- ^ a b Richardson, Joe M. (1986), Christian Reconstruction: The American Missionary Association and Southern Blacks, 1861–1890.

- ^ Hampton Negro Conference (1901). Browne, Hugh; Kruse, Edwina; Walker, Thomas C.; Moton, Robert Russa; Wheelock, Frederick D. (eds.). Annual Report of the Hampton Negro Conference. Vol. 5. Hampton, Virginia: Hampton Institute Press. p. 59. hdl:2027/chi.14025704. Alt URL

- ^ Anderson 1988, pp. 33–78.

- ^ Freeman, Kassie (1998). African American Culture and Heritage in Higher Education Research and Practice. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 146. ISBN 9780275958442.

- ^ Hornsby, Alton (2011). Black America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 633. ISBN 9780313341120.

- ^ Du Bois, W.E. Burghardt; Augustus Granville Dill, eds. (1910). The College-bred Negro America. pp. 29, 45, 66–70, 73, 75–81, 99.

- ^ Gasman, Marybethn, "Swept under the rug? A historiography of gender and Black colleges." American Educational Research Journal 44#4 (2007): 760–805. online

- ^ a b Negro Year Book: An Annual Encyclopedia of the Negro ... 1913. p. 180.

- ^ "George Peabody Library History". Johns Hopkins University. Archived from the original on 2010-06-04. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

After the Civil War he funded the Peabody Education Fund which established public education in the South.

- ^ Negro Year Book: An Annual Encyclopedia of the Negro ... 1913. p. 181.

- ^ Anderson, Eric, and Alfred A. Moss (1999), Dangerous donations: Northern philanthropy and southern Black education, 1902–1930.

- ^ Hampton Negro Conference (1901). Browne, Hugh; Kruse, Edwina; Walker, Thomas C.; Moton, Robert Russa; Wheelock, Frederick D. (eds.). Annual Report of the Hampton Negro Conference. Vol. 5. Hampton, Virginia: Hampton Institute Press. p. 57. hdl:2027/chi.14025704. Alt URL

- ^ Hahn (2003), A Nation under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South, from Slavery to the Great Migration, pp. 230–34.

- ^ Giggie, John M. (2007), After redemption: Jim Crow and the transformation of African American religion in the Delta, 1875–1915. [ DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195304039.001.0001 online]

- ^ Bailey, Kenneth (1977), "The Post–Civil War Racial Separations in Southern Protestantism," Church History, 46#4, pp. 453–73. in JSTOR

- ^ Lincoln, C. Eric, and Lawrence H. Mamiya (1990), The Black Church in the African American Experience (Duke University Press).

- ^ a b Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks, Righteous Discontent: The Women's Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920 (1993).

- ^ Montesano, Philipp M. (1973), "San Francisco Black Churches in the Early 1860s" California Historical Quarterly, 52#2 pp. 145–152.

- ^ Chandler, Robert J. (1982), "Friends in Time of Need: Republicans and Black Civil Rights in California during the Civil War Era" Arizona & the West, 24#4, pp. 319–340. in JSTOR

- ^ Stowell, Daniel W. (1998). Rebuilding Zion : The Religious Reconstruction of the South, 1863-1877. Oxford UP. pp. 83–84. ISBN 9780198026211.

- ^ Walker, Clarence Earl (1982), A Rock in a Weary Land: The African Methodist Episcopal Church During the Civil War and Reconstruction.

- ^ Sweet, William W. (1914), "The Methodist Episcopal Church and Reconstruction," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 7#3 pp. 147–165. in JSTOR at p.

- ^ Grant, Donald Lee (1993). The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia. U. of Georgia Press. p. 264. ISBN 9780820323299.

- ^ Foner, Eric (1988), Reconstruction: America's unfinished revolution, 1863–1877, p. 93.

- ^ Angell, Stephen Ward (1992), Henry McNeal Turner and African-American Religion in the South.

- ^ Redkey, Edwin S., "Bishop Turner's African Dream." Journal of American History 54#2 (1967): 271–290. in JSTOR

- ^ Johnson, Andre E. (2015), "God is a Negro: The (Rhetorical) Black Theology of Bishop Henry McNeal Turner." Black Theology 13.1 (2015): 29–40.

- ^ Johnson, Andre E. (2012), The Forgotten Prophet: Bishop Henry McNeal Turner and the African American Prophetic Tradition.

- ^ Brown, Jr., Canter, and Larry Eugene Rivers (2004), For a Great and Grand Purpose: The Beginnings of the AMEZ Church in Florida, 1864–1905.

- ^ Hackett, David G. (2000), "The Prince Hall Masons and the African American Church: The Labors of Grand Master and Bishop James Walker Hood, 1831–1918." Church History, 69#4: 770–802. online

- ^ Sommerville, Raymond R., An Ex-colored Church: Social Activism in the CME Church, 1870–1970 (Mercer University Press, 2004).

- ^ Foner (1988), Reconstruction: America's unfinished revolution, 1863–1877, pp. 282–83.

- ^ Brooks, Walter H. (1922), "The Evolution of the Negro Baptist Church", Journal of Negro History 7#1: 11–22. free in JSTOR

- ^ Kidd, Thomas S.; Barry Hankins (2015). Baptists in America: A History. Oxford University Press. pp. 149–66. ISBN 978-0-19-997753-6.

- ^ Martin, Sandy Dwayne (1989), Black Baptists and African Missions: The Origins of a Movement, 1880–1915 .

- ^ Hamilton, Shirley (2009), "African American Women Roles In The Baptist Church: Equality Within the National Baptist Convention, USA." (MA Thesis, Wake Forest University). online

- ^ a b c d Rabinowitz, Howard N. (1978), Race Relations in the Urban South: 1865–1890, pp. 208-213.

- ^ Myrdal, Gunnar (1944). An American Dilemma. Harber & Brothers. pp. 858–78.

- ^ Fallin Jr., Wilson (2007), Uplifting the People: Three Centuries of Black Baptists in Alabama, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Howard N. Rabinowitz, "From exclusion to segregation: Southern race relations, 1865–1890." Journal of American History 63#2 (1976): 325-350. in JSTOR

- ^ Richard E. Welch, "The Federal Elections Bill of 1890: Postscripts and Prelude." Journal of American History 52#3 (1965): 511-526. in JSTOR

- ^ Jane Elizabeth Dailey, Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, and Bryant Simon, Jumpin'Jim Crow: Southern politics from civil war to civil rights (2000).

- ^ J. Morgan Kousser, "Plessy v. Ferguson." Dictionary of American History (2003) 6: 370-371. online Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Peter Wallenstein, "Reconstruction, Segregation, and Miscegenation: Interracial Marriage and the Law in the Lower South, 1865–1900." American Nineteenth Century History 6#1 (2005): 57-76.

- ^ C. Vann Woodward, The strange career of Jim Crow (1955; 3rd ed. 1974) online

- ^ Sitkoff, Howard (2008). "Up from Slavery". The Struggle for Black Equality (3rd ed.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9781429991919.

- ^ Roger A. Fischer, "A pioneer protest: the New Orleans street-car controversy of 1867." Journal of Negro History 53#3 (1968): 219-233. in JSTOR

- ^ Volk, Kyle G. (2014). Moral Minorities and the Making of American Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 148, 150-153, 155-159, 162-164. ISBN 019937192X.

- ^ Elaine Elinson, San Francisco's own Rosa Parks, San Francisco Chronicle, January 16, 2012

- ^ Johnson, Jason B. (February 10, 2005). "A day for 'mother of civil rights' / Entrepreneur sued to desegregate streetcars in 1860s". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ Duster, Alfreda (1970). Crusade for Justice. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. xviii. ISBN 978-0-226-89344-0.

- ^ Fleming, Maria, A Place at the Table: Struggles for Equality in America, Oxford University Press, USA, 2001, p. 36

- ^ see "Lynchings: By State and Race, 1882-1968". University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Archived from the original on 2010-06-29. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

Statistics provided by the Archives at Tuskegee Institute.

; also Lynchings by year - ^ Brundage, W. Fitzhugh (1993). Lynching in the new South. University of Illinois Press. pp. 103–190. ISBN 9780252063459.

- ^ Elwood M. Beck and Stewart E. Tolnay. "The killing fields of the deep south: the market for cotton and the lynching of blacks, 1882–1930." American Sociological Review (1990): 526-539. online

- ^ Jacqueline Jones Royster, ed., Southern horrors and other writings: The anti-lynching campaign of Ida B. Wells, 1892–1900 (1997), with primary and secondary documents.

- ^ Robert L. Zangrando, The NAACP crusade against lynching, 1909–1950 (1980).

- ^ Eric Foner, "Introduction," to Rayford W. Logan The Betrayal of the Negro, from Rutherford B. Hayes to Woodrow Wilson (1997). p. xiv online. Foner's 1997 introduction is paraphrasing the 1965 2nd edition of Logan's book.

- ^ Norrel, Robert J. (2005). The House I Live In : Race in the American Century. Oxford UP. p. 50. ISBN 9780198023777.

- ^ Ronald W. Walters and Robert C. Smith, African American Leadership (1999) p 13.

- ^ Hahn, Steven (2003). A Nation Under Our Feet. Harvard University Press. p. 261. ISBN 9780674011694.

- ^ Howard N. Rabinowitz, Race, Ethnicity, and Urbanization: Selected Essays (1994), p. 183

- ^ Washington, Mary Helen (1988). A Voice from the South: Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. xxvii–liv. ISBN 978-0-19-506323-3.

- ^ a b Ritchie, Joy; Ronald, Kate (2001). Available Means: An Anthology of Women's Rhetoric(s). Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-0-8229-5753-9.

- ^ Roy E. Finkenbine. "Douglass, Frederick"; American National Biography Online 2000. Accessed March 16, 2016

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b Text of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) is available from: Cornell CourtListener Findlaw Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress

- ^ Text of Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) is available from: Cornell CourtListener Findlaw Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress OpenJurist Oyez (oral argument audio)

- ^ Text of Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) is available from: CourtListener Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress OpenJurist

Further reading

[edit]- Brown, Nikki L.M., and Barry M. Stentiford, eds. The Jim Crow Encyclopedia (Greenwood, 2008)

- Carle, Susan D. Defining the Struggle: National Racial Justice Organizing, 1880–1915 (Oxford UP, 2013). 404pp.

- Davis, Hugh. "We will be satisfied with nothing less": the African American struggle for equal rights in the North during Reconstruction. (2011).

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619-1895 (3 vol. 2006) 700 articles by experts

- Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution. Harper and Row. ISBN 9780062383235.

- Foner, Eric. "Rights and the Constitution in Black Life during the Civil War and Reconstruction". Journal of American History 74.3 (1987): 863–883. online

- Frankel, Noralee. Break Those Chains at Last: African Americans 1860–1880 (1996). excerpt; for high school audience

- Hahn, Steven. A nation under our feet: Black political struggles in the rural South, from slavery to the great migration (2003); Pulitzer Prize; excerpt; online review

- Jenkins, Jeffery A., Justin Peck, and Vesla M. Weaver. "Between Reconstructions: Congressional Action on Civil Rights, 1891–1940." Studies in American Political Development 24#1 (2010): 57–89. online Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Logan, Rayford. The Betrayal of the Negro from Rutherford B. Hayes to Woodrow Wilson (2nd ed. 1965).

- Lowery, Charles D. Encyclopedia of African-American civil rights: from emancipation to the present (Greenwood, 1992). online

- Raffel, Jeffrey. Historical dictionary of school segregation and desegregation: The American experience (Bloomsbury, 1998) online

- Strickland, Arvarh E., and Robert E. Weems, eds. The African American Experience: An Historiographical and Bibliographical Guide (Greenwood, 2001). 442pp; 17 topical chapters by experts.

- Swinney, Everette. "Enforcing the Fifteenth Amendment, 1870–1877." Journal of Southern History 28#2 (1962): 202–218. in JSTOR.

- Woodward, C. Vann. Origins of the New South, 1877–1913 (1951).

Leadership

[edit]- Chesson, Michael B. "Richmond's Black Councilman, 1871–96," in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982) pp 191–222.

- Dray, Philip. Capitol men: the epic story of Reconstruction through the lives of the first Black congressmen (2010).

- Foner, Eric. Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders during Reconstruction (1993).

- Gatewood, Willard B. (2000). Aristocrats of color: the Black elite, 1880-1920. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 9781610750257.

- Holt, Thomas. Black over white: Negro political leadership in South Carolina during Reconstruction (1979).

- Holt, Thomas C. "Negro State Legislators in South Carolina during Reconstruction," in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982) pp 223–49.

- Hume, Richard L. "Negro delegates to the state constitutional conventions of 1867–69," in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982) pp 129–54

- Hume, Richard L. and Jerry B. Gough. Black people, Carpetbaggers, and Scalawags: The Constitutional Conventions of Radical Reconstruction (LSU Press, 2008); statistical classification of delegates.

- Jenkins, Jeffery A., and Boris Heersink. "Republican Party Politics and the American South: From Reconstruction to Redemption, 1865–1880." (2016 paper t the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Southern Political Science Association); online.

- Loewenberg, Bert James and Ruth Bogin. Black Women in Nineteenth-Century American Life: Their Words, Their Thoughts, Their Feelings (Pennsylvania State UP, 1976).

- Meir, August. "Afterword: New Perspectives on the Nature of Black Political Leadership during Reconstruction." in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982) ppe 393–406.

- Pitre, Merline. Through Many Dangers, Toils, and Snares: The Black Leadership of Texas, 1868–1900 Eakin Press, 1985.

- Rabinowitz, Howard N., ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982), 422 pages; 16 chapters by experts, on leaders and key groups.

- Rankin, David C. "The origins of Negro leadership in New Orleans during Reconstruction," in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982) 155–90.

- Smith, Jessie Carney, ed. Encyclopedia of African American Business (2 vol. Greenwood 2006). excerpt

- Vincent, Charles. "Negro Leadership and Programs in the Louisiana Constitutional Convention of 1868." Louisiana History (1969): 339–351. in JSTOR

- Walters, Ronald W.; Robert C. Smith (1999). African American leadership. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791441459.

Individual leaders

[edit]- Anderson, Eric. "James O'Hara of North Carolina: Black Leadership and local government" in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982) 101–128.

- Brock, Euline W. "Thomas W. Cardozo: Fallible Black Reconstruction Leader." Journal of Southern History 47.2 (1981): 183–206. in JSTOR

- Grosz, Agnes Smith. "The Political Career of Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback." Louisiana Historical Quarterly 27 (1944): 527–612.

- Harlan, Louis R. Booker T. Washington: The Making of a Black Leader, 1856–1901 (1972).

- Harris, William C. "Blanche K. Bruce of Mississippi: Conservative Assimilationist." in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982). 3-38.

- Harris, William C. "James Lynch: Black Leader in Southern Reconstruction," Historian (1971) 34#1 pp 40–61, DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-6563.1971.tb00398.x

- Haskins, James. Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback (1973).

- Hine, William C. "Dr. Benjamin A. Boseman, Jr.: Charleston's Black Physician-Politician," in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982) pp 335–62.

- Klingman, Peter D. "Race and Faction in the Public Career of Florida's Josiah T. Walls." in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982). 59–78.

- Klingman, Peter D. Josiah Walls: Florida's Black Congressman of Reconstruction (1976).

- Lamson, Peggy. The Glorious Failure: Black Congressman Robert Brown Elliott and the Reconstruction in South Carolina (1973).

- McFeely, William S. Frederick Douglass (1995).

- Moneyhon, Carl H. "George T. Ruby and the Politics of Expediency in Texas," in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982) pp 363–92.

- Norrell, Robert J. "Booker T. Washington: Understanding the Wizard of Tuskegee," Journal of Black people in Higher Education 42 (2003–4) pp. 96–109 in JSTOR

- Norrell, Robert J. Up from history: The life of Booker T. Washington (2009).

- Reidy, Joseph P. "Karen A. Bradley: Voice of Black Labor in the Georgia Lowcountry," in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982) pp 281–309.

- Richardson, Joe M. "Jonathan C. Gibbs: Florida's Only Negro Cabinet Member." Florida Historical Quarterly 42.4 (1964): 363–368. in JSTOR

- Russell, James M. and Thornbery, Jerry. "William Finch of Atlanta: The Black Politician as Civic Leader," in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982) pp 309–34.

- Schweninger, Loren. "James Rapier of Alabama and the Noble Cause of Reconstruction," in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982). 79–100.

- Woody, Robert H. "Jonathan Jasper Wright, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of South Carolina, 1870–77." Journal of Negro History 18.2 (1933): 114–131. in JSTOR

- White, Richard C. (2017). The Republic for Which It Stands. Oxford University Press.

Gender

[edit]- Bond, Beverly G. "'Every Duty Incumbent Upon Them': African-American Women in Nineteenth Century Memphis." Tennessee Historical Quarterly 59.4 (2000): 254.

- Clinton, Catherine. "Bloody terrain: Freedwomen, sexuality and violence during reconstruction." Georgia Historical Quarterly 76.2 (1992): 313–332. in JSTOR

- Edwards, Laura F. Gendered Strife and Confusion: The Political Culture of Reconstruction (1997).

- Farmer-Kaiser, Mary. Freedwomen and the Freedmen's Bureau: Race, Gender, and Public Policy in the Age of Emancipation (Fordham Univ Press, 2010). online review

- Frankel, Noralee. Freedom's women: Black women and families in Civil War era Mississippi (1999).

- Hunter, Tera W. To 'Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women's Lives and Labors after the Civil War (Harvard University Press, 1997).

- Oglesby, Catherine. "Gender and History of the Postbellum US South." History Compass 8.12 (2010): 1369–1379; historiography, mostly of white women.

- Olson, Lynne. Freedom's daughters: The unsung heroines of the civil rights movement from 1830 to 1970 (2001).

State and local studies

[edit]- Cresswell, Stephen. Multiparty Politics in Mississippi, 1877–1902 (1995).

- Davis, D. F., et al. "Before the Ghetto: Black Detroit in the Nineteenth Century." Urban History Review (1977) 6#1 pp. 99–106 in JSTOR

- Doyle, Don H. New Men, New Cities, New South: Atlanta, Nashville, Charleston, Mobile, 1860–1910 (1990) excerpt

- Drago, Edmund L. Black Politicians and Reconstruction in Georgia: A Splendid Failure (1992)

- Green, Hilary. Educational Reconstruction: African American Schools in the Urban South, 1865–1890 (Fordham UP, 2016), Case studies of Richmond, Virginia, and Mobile, Alabama. online review

- Hornsby Jr., Alton, ed. Black America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia (2 vol 2011) excerpt

- Hornsby Jr., Alton. A Short History of Black Atlanta, 1847–1993 (2015).

- Jenkins, Wilbert L. Seizing the New Day: African Americans in Post–Civil War Charleston. (2003).

- Jewell, Joseph O. Race, social reform, and the making of a middle class: The American Missionary Association and Black Atlanta, 1870–1900 (2007).

- Rabinowitz, Howard N. Race Relations in the Urban South: 1865–1890 (1978)

- Wharton, Vernon Lane. The Negro in Mississippi: 1865–1890 (1947)

Primary sources

[edit]- Foner, Philip, ed. The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass: Reconstruction and After (1955).

- Smith, John David. We Ask Only for Even-handed Justice: Black Voices from Reconstruction, 1865–1877 (2nd ed. 2014)

- Work, Monroe N. (1912). Negro Year Book and Annual Encyclopedia of the Negro., First edition was 1913.

- Reid, Whitelaw (1866). After the War: A Southern Tour., detailed coverage by Yankee journalist, with focus on Freedmen.

- Richardson, Joe M. (1965). "The Negro in Post Civil-War Tennessee: A Report by a Northern Missionary". Journal of Negro Education. 34 (4): 419–424. doi:10.2307/2294093. JSTOR 2294093.

- Wells-Barnett, Ida B. Southern horrors and other writings: the anti-lynching campaign of Ida B. Wells, 1892–1900. Ed. Jacqueline Jones Royster. Bedford Books, 1997.

- Winegarten, Ruthie, ed. (2014). Black Texas Women: A Sourcebook. University of Texas Press. pp. 44–69. ISBN 9780292785564.

External links

[edit]- "African American Perspectives: Pamphlets from the Daniel A. P. Murray Collection, 1818–1907" Most are from 1875 to 1900.

- Booker T. Washington Papers, vol 1-3

- "Booker T. Washington: The Man and the Myth Revisited." (2007) PowerPoint presentation By Dana Chandler

- Civil Rights Resource Guide, from the Library of Congress

- "The Long History of the African American Civil Rights Movement in Florida" Archived 2016-01-10 at the Wayback Machine

KSF