Classification of Romance languages

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 27 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 27 min

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2010) |

| Romance | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution |  |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | roma1334 |

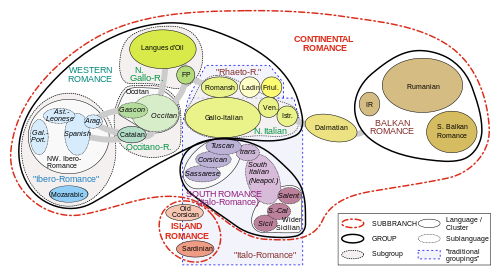

The internal classification of the Romance languages is a complex and sometimes controversial topic which may not have one single answer. Several classifications have been proposed, based on different criteria.

Attempts at classifying Romance languages

[edit]

Difficulties of classification

[edit]The comparative method used by linguists to build family language trees is based on the assumption that the member languages evolved from a single proto-language by a sequence of binary splits, separated by many centuries. With that hypothesis, and the glottochronological assumption that the degree of linguistic change is roughly proportional to elapsed time, the sequence of splits can be deduced by measuring the differences between the members.

However, the history of Romance languages, as we know it, makes the first assumption rather problematic. While the Roman Empire lasted, its educational policies and the natural mobility of its soldiers and administrative officials probably ensured some degree of linguistic homogeneity throughout its territory. Even if there were differences between the Vulgar Latin spoken in different regions, it is doubtful whether there were any sharp boundaries between the various dialects. On the other hand, after the Empire's collapse, the population of Latin speakers was separated—almost instantaneously, by the standards of historical linguistics—into a large number of politically independent states and feudal domains whose populations were largely bound to the land. These units then interacted, merged and split in various ways over the next fifteen centuries, possibly influenced by languages external to the family (as in the so-called Balkan language area).

In summary, the history of Latin and Romance-speaking peoples can hardly be described by a binary branching pattern; therefore, one may argue that any attempt to fit the Romance languages into a tree structure is inherently flawed.[1] In this regard, the genealogical structure of languages forms a typical linkage.[2]

On the other hand, the tree structure may be meaningfully applied to any subfamilies of Romance whose members did diverge from a common ancestor by binary splits. That may be the case, for example, of the dialects of Spanish and Portuguese spoken in different countries, or the regional variants of spoken standard Italian (but not the so-called "Italian dialects", which are distinct languages that evolved directly from Vulgar Latin).

Criteria

[edit]The two main avenues to attempt classifications are historical and typological criteria:[3]

- Historical criteria look at the Romance languages' former development. For example, a widely employed model divided the Romance-speaking world between West and East based on whether plural nouns end in -s or in a vowel. Researchers have highlighted this is mainly valid from a historical point of view as the change appeared in Antiquity in the East (Italo-Romance, Dalmatian and Eastern Romance), while in the West plural nouns ending in -s were preserved past this stage but could be lost by more recent changes (such as aspiration of word-final -s in some varieties of Spanish and its phonetic loss in French).[4] Another criterion taken into account is the distinction between conservative and innovative/progressive Romance languages. Generally, the Gallo-Romance languages (discussed further below) form the core "innovative" languages, with standard French often considered the most innovative of all. The phenomenon is attributed to language development in the Carolingian Empire with Northern Italy and Catalan region representing marginal areas of distribution. For example, Catalan, up to the thirteenth century, used the Romance writing modes common in the Occitan area. This created a contrast with the languages near the periphery (which include Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and Romanian) which are deemed as "conservative".[5] Sardinian is generally acknowledged as the most conservative Romance languages, at least from a phonetic point of view. Dante famously denigrated the Sardinians for the conservativeness of their speech, remarking that they imitate Latin "like monkeys imitate men".[6][7] According to Gerhard Rohlfs France replaced Italy as a centre of diffusion of innovations around the sixth century.[8]

- Typological criteria measure the structural features of Romance languages, mainly in synchrony. For example, the identification of the La Spezia–Rimini Line line, which is generally accepted as the main isogloss for consonantal lenition in Romance languages and which runs across north-central Italy just to the north of the city of Florence (whose speech forms the basis of standard Italian). In this scheme, "East" includes the languages of central and southern Italy, and the Eastern Romance languages in Romania, Greece, and elsewhere in the Balkans; "West" includes the languages of Portugal, Spain, France, northern Italy and Switzerland.[9] Sardinian does not fit at all into this sort of division.[10] Further expansions on this are discussed below.

The standard proposal

[edit]By applying the comparative method, some linguists have concluded that Sardinian became linguistically developed separately from the remainder of the Romance languages at an extremely early date.[11] Among the many distinguishing features of Sardinian are its articles (derived from Latin IPSE instead of ILLE) and lack of palatalization of /k/ and /ɡ/ before /i e ɛ/[12] and other unique conservations such as domo ‘house’ (< domo).[13] Sardinian has plurals in /s/ but post-vocalic lenition of voiceless consonants is normally limited to the status of an allophonic rule, which ignores word boundaries (e.g. [k]ane 'dog' but su [ɡ]ane or su [ɣ]ane 'the dog'), and there are a few innovations unseen elsewhere, such as a change of /au/ to /a/.[14] This view is challenged in part by the existence of definite articles continuing ipse forms (e.g. sa mar 'the sea') in some varieties of Catalan, best known as typical of Balearic dialects. Sardinian also shares develarisation of earlier /kw/ and /ɡw/ with Romanian: Sard. abba, Rom. apă 'water'; Sard. limba, Rom. limbă 'language' (cf. Italian acqua, lingua).

According to this view, the next split was between Common Romanian in the east, and the other languages (the Italo-Western languages) in the west. One of the characteristic features of Romanian is its retention of three of Latin's seven noun cases. The third major split was more evenly divided, between the Italian branch, which comprises many languages spoken in the Italian Peninsula, and the Gallo-Iberian branch.

Another proposal

[edit]However, this is not the only view. Another common classification begins by splitting the Romance languages into two main branches, East and West. The East group includes Romanian, the languages of Corsica and Sardinia,[9] and all languages of Italy south of a line through the cities of Rimini and La Spezia (see La Spezia–Rimini Line). Languages in this group are said to be more conservative, i.e. they retained more features of the original Latin.

The West group split into a Gallo-Romance group, which became the Oïl languages (including French), Gallo-Italian, Occitan, Franco-Provençal and Romansh, and an Iberian Romance group which became Spanish and Portuguese.

Italo-Western vs. Eastern vs. Southern

[edit]A three-way division is made primarily based on the outcome of Vulgar Latin (Proto-Romance) vowels:

| Classical Latin | Proto-Romance | Southern | Italo-Western | Eastern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| short A | */a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ |

| long A | ||||

| short E | */ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/ |

| long E | */e/ | /e/ | /e/ | |

| short I | */ɪ/ | /i/ | ||

| long I | */i/ | /i/ | /i/ | |

| short O | */ɔ/ | /ɔ/ | /ɔ/ | /o/ |

| long O | */o/ | /o/ | ||

| short U | */ʊ/ | /u/ | /u/ | |

| long U | */u/ | /u/ |

Italo-Western is in turn split along the so-called La Spezia–Rimini Line in northern Italy,[15] which is a bundle of isoglosses separating the central and southern Italian languages from the so-called Western Romance languages to the north and west. Some noteworthy differences between the two are:

- Phonemic lenition of intervocalic stops, which happens to the northwest but not to the southeast.

- Degemination of geminate stops (producing new intervocalic single voiceless stops, after the old ones were lenited), which again happens to the northwest but not to the southeast.

- Deletion of intertonic vowels (between the stressed syllable and either the first or last syllable), again in the northwest but not the southeast.

- Use of plurals in /s/ in the northwest vs. plurals using vowel change in the southeast.

- Development of palatalized /k/ before /e,i/ to /(t)s/ in the northwest vs. /tʃ/ in the southeast.

- Development of /kt/, which develops to /xt/ > /it/ (sometimes progressing further to /tʃ/) in the northwest but /tt/ in the southeast.

Recent scholarship argues for a more nuanced view. All of the "southeast" characteristics apply to all languages southeast of the line, and all of the "northwest" characteristics apply to all languages in France and (most of) Spain yet the Gallo-Italic languages are somewhere in between. These languages do have the "northwest" characteristics of lenition and loss of gemination however other seemingly clear boundaries are often obscured by local variations:[16]

- The Gallo‒Italic languages have vowel-changing plurals rather than /s/ plurals.

- The Lombard language in north-central Italy and the Rhaeto-Romance languages have the "southeast" characteristic of /tʃ/ instead of /(t)s/ for palatalized /k/.

- The Venetian language in northeast Italy and some of the Rhaeto-Romance languages have the "southeast" characteristic of developing /kt/ to /tt/.

- Lenition of post-vocalic /p t k/ is widespread as an allophonic phonetic realization in Italy below the La Spezia-Rimini line, including Corsica and most of Sardinia.

The likely cause for this partition is that the focal point of innovation was located in central France and was related directly to the level of Carolingian influence, from which a series of innovations spread out as areal changes. The La Spezia–Rimini Line would then represent the farthest point to the southeast that these innovations reached, corresponding to the northern chain of the Apennine Mountains, which cuts straight across northern Italy and forms a major geographic barrier to further language spread. This would explain why some of the "northwest" features (almost all of which can be characterized as innovations) end at differing points in northern Italy, and why some of the languages in geographically remote parts of Spain (in the south, and high in the Pyrenees) are lacking some of these features. It also explains why the languages in France (especially standard French) seem to have innovated earlier and more extensively than other Western Romance languages.[17]

On top of this, the medieval Mozarabic language in southern Spain, at the far end of the "northwest" group, may have had the "southeast" characteristics of lack of lenition and palatalization of /k/ to /tʃ/.[18] Certain languages around the Pyrenees (e.g. some highland Aragonese dialects) also lack lenition, and northern French dialects such as Norman and Picard have palatalization of /k/ to /tʃ/ (although this is possibly an independent, secondary development, since /k/ between vowels, i.e. when subject to lenition, developed to /dz/ rather than /dʒ/, as would be expected for a primary development).[19]

Many of the "southeast" features also apply to the Eastern Romance languages (particularly, Romanian), despite the geographic discontinuity. Examples are lack of lenition, maintenance of intertonic vowels, use of vowel-changing plurals, and palatalization of /k/ to /tʃ/. This has led some researchers, following Walther von Wartburg, to postulate a basic two-way east–west division, with the "Eastern" languages including Romanian and central and southern Italian, although this view is troubled by the contrast of numerous Romanian phonological developments with those found in Italy below the La Spezia-Rimini line. Among these features, in Romanian geminates reduced historically to single units, and /kt/ developed into /pt/, whereas in central and southern Italy geminates are preserved and /kt/ underwent assimilation to /tt/.[20]

The wave hypothesis

[edit]Linguists like Jean-Pierre Chambon claim that the various regional languages did not evolve in isolation from their neighbours; on the contrary, they see many changes propagating from the more central regions (Italy and France) towards the periphery (Iberian Peninsula and Romania).[21] These authors see the Romance family as a linkage rather than a tree-like family, and insist that the Wave model is better suited than the Tree model for representing the history of Romance.

Degree of separation from Latin

[edit]In a study by linguist Mario Pei (1949), the degrees of phonological modification of stressed vowels of seven Romance languages with respect to Vulgar Latin were found to be as follows (with higher percentages indicating greater divergence from the stressed vowels of Vulgar Latin):[22][23]

The study emphasized, however, that it represented only "a very elementary, incomplete and tentative demonstration" of how statistical methods could measure linguistic change, assigned "frankly arbitrary" point values to various types of change, and did not compare languages in the sample with respect to any characteristics or forms of divergence other than stressed vowels, among other caveats.[24]

Some major linguistic features differing among Romance languages

[edit]Part of the difficulties met in classifying Romance languages is due to the seemingly messy distribution of linguistic innovations across members of the Romance family. While this is a problem for followers of the dominant Tree model, this is in fact a characteristic typical of linkages and dialect continuums generally: this has been an argument for approaching this family with the tools based on the Wave model, including dialectology and Historical glottometry.

What follows is a sample of some significant linguistic traits (innovations since Vulgar Latin) that run across the Romance linkage.

The differences among Romance languages occur at all levels, including the sound systems, the orthography, the nominal, verbal, and adjectival inflections, the auxiliary verbs and the semantics of verbal tenses, the function words, the rules for subordinate clauses, and, especially, in their vocabularies. While most of those differences are clearly due to independent development after the breakup of the Roman Empire (including invasions and cultural exchanges), one must also consider the influence of prior languages in territories of Latin Europe that fell under Roman rule, and possible heterogeneity in Vulgar Latin itself.

Romanian, together with other related languages, like Aromanian, has a number of grammatical features which are unique within Romance, but are shared with other non-Romance languages of the Balkans, such as Albanian, Bulgarian, Greek, Macedonian, Serbo-Croatian and Turkish. These include, for example, the structure of the vestigial case system, the placement of articles as suffixes of the nouns (cer = "sky", cerul = "the sky"), and several more. This phenomenon, called the Balkan language area, may be due to contacts between those languages in post-Roman times.

Formation of plurals

[edit]Some Romance languages form plurals by adding /s/ (derived from the plural of the Latin accusative case), while others form the plural by changing the final vowel (by influence of Latin nominative plural endings, such as /i/) from some masculine nouns.

- Plural in /s/: Portuguese, Galician, Spanish, Catalan,[25] Occitan, Sardinian, Friulian, Romansh.

- Special case of French: Falls into the first group historically (and orthographically), but the final -s is no longer pronounced (except in liaison contexts), meaning that singular and plural nouns are usually homophonous in isolation. Many determiners have a distinct plural formed by both changing the vowel and allowing /z/ in liaison.

- Vowel change: Italian, Neapolitan, Sicilian, Romanian.

Words for "more"

[edit]Some Romance languages use a version of Latin plus, others a version of magis.

- Plus-derived: French plus /plys/, Italian più /pju/, Sardinian prus /ˈpruzu/, Piedmontese pi, Lombard pu, Ligurian ciù, Neapolitan chiù, Friulian plui, Romansh pli, Venetian pi. In Catalan pus /pus/ is exclusively used in negative statements in the Mallorcan dialect, and "més" is the word mostly used.

- Magis-derived: Galician and Portuguese (mais; medieval Galician-Portuguese had both words: mais and chus), Spanish (más), Catalan (més), Venetian (massa or masa, "too much") Occitan (mai), Romanian (mai).

Words for "nothing"

[edit]Although the Classical Latin word for "nothing" is nihil, the common word for "nothing" became nulla in Italian (from neuter plural nulla, "no thing",[26] or from nulla res;[27] Italian also has the word "niente"), nudda [ˈnuɖːa] in Sardinian, nada in Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician (from (rem) natam, "thing born";[28] Galician also has the word "ren"), rien in French, res in Catalan, cosa and res in Aragonese, ren in Occitan (from rem, "thing",[29] or else from nominative res),[30] nimic in Romanian, nagut in Romansh, gnente in Venetian and Piedmontese, gnent and nagott in Lombard, and nue and nuie in Friulian. Some argue that most roots derive from different parts of a Latin phrase nullam rem natam ("no thing born"), an emphatic idiom for "nothing".[citation needed] Meanwhile, Italian and Venetian niente and gnente would seem to be more logically derived from Latin ne(c) entem ("no being"), ne inde or, more likely, ne(c) (g)entem, which also explains the French cognate word néant.[31][32] The Piedmontese negative adverb nen also comes directly from ne(c) (g)entem,[27] while gnente is borrowed from Italian.

The number 16

[edit]Romanian constructs the names of the numbers 11–19 by a regular Slavic-influenced pattern that could be translated as "one-over-ten", "two-over-ten", etc. All the other Romance languages use a pattern like "one-ten", "two-ten", etc. for 11–15, and the pattern "ten-and-seven, "ten-and-eight", "ten-and-nine" for 17–19. For 16, however, they split into two groups: some use "six-ten", some use "ten-and-six":[33]

- "Sixteen": Italian sedici, Catalan and Occitan setze, French seize, Venetian sédexe, Romansh sedesch, Friulian sedis, Lombard sedas / sedes, Franco-Provençal sèze, Sardinian sèighi, Piedmontese sëddes (sëddes is borrowed from Lombard and replaced the original sëzze since the 18th century, such as the numbers from 11 to 16, onze but now óndes, dose but now dódes, trëzze but now tërdes, quatòrze but now quatòrdes, quinze but now quìndes).

- "Ten and six": Portuguese dezasseis or dezesseis, Galician dezaseis (decem ac sex), Spanish dieciséis (Romance construction: diez y seis), the Marchigiano dialect digissei.

- "Six over ten": Romanian șaisprezece (where spre derives from Latin super).

Classical Latin uses the "one-ten" pattern for 11–17 (ūndecim, duodecim, ..., septendecim), but then switches to "two-off-twenty" (duodēvigintī) and "one-off-twenty" (ūndēvigintī). For the sake of comparison, note that many of the Germanic languages use two special words derived from "one left over" and "two left over" for 11 and 12, then the pattern "three-ten", "four-ten", ..., "nine-ten" for 13–19.

To have and to hold

[edit]The verbs derived from Latin habēre "to have", tenēre "to hold", and esse "to be" are used differently in the various Romance languages, to express possession, to construct perfect tenses, and to make existential statements ("there is").[34][35] If we use T for tenēre, H for habēre, and E for esse, we have the following distribution:

- HHE: Romanian, Italian, Gallo-Italic languages.

- HHH: Occitan, French, Romansh, Sardinian.

- THH: Spanish, Catalan, Aragonese.

- T-H/T-T: Portuguese.

For example:

| Language | Possessive predicate |

Perfect | Existential | Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | I have | I have done | There is | HHE |

| Italian | (io) ho | (io) ho fatto | c'è | HHE |

| Friulian | (jo) o ai | (jo) o ai fat | a 'nd è, al è | HHE |

| Venetian | (mi) go | (mi) go fato | ghe xe, ghi n'é | HHE |

| Lombard (Western) | (mi) a gh-u | (mi) a u fai | al gh'è, a gh'è | HHE |

| Piedmontese | (mi) i l'hai | (mi) i l'hai fàit | a-i é | HHE |

| Romanian | (eu) am | (eu) am făcut | este / e | HHE |

| Neapolitan | (ijo) tengo | (ijo) aggio fatto | ce sta[36] | TH– |

| Sardinian | (deo) apo (deu) apu |

(deo) apo fattu (deu) apu fattu |

bi at / bi est nc(h)'at / nc(h)'est |

HHH |

| Romansh | (jau) hai | (jau) hai fatg | igl ha | HHH |

| French | j'ai | j'ai fait | il y a | HHH |

| Catalan | (jo) tinc | (jo) he fet | hi ha | THH |

| Aragonese | (yo) tiengo (yo) he (dialectally) |

(yo) he feito | bi ha | THH |

| Spanish | (yo) tengo | (yo) he hecho | hay | THH |

| Galician | (eu) teño | — [no present perfect] |

hai | T–H |

| Portuguese | (eu) tenho | — [no present perfect] |

há/tem | T–H or T–T |

Ancient Galician-Portuguese used to employ the auxiliary H for permanent states, such as Eu hei um nome "I have a name" (i.e. for all my life), and T for non-permanent states Eu tenho um livro "I have a book" (i.e. perhaps not so tomorrow), but this construction is no longer used in modern Galician and Portuguese. Portuguese also uses the T verb even in the existential sense, e.g. Tem água no copo "There is water in the glass". Sardinian employs both H and E for existential statements, with different degrees of determination.

Languages that have not grammaticalised *tenēre have kept it with its original sense "hold", e.g. Italian tieni il libro, French tu tiens le livre, Romanian ține cartea, Friulian Tu tu tegnis il libri "You're holding the book". The meaning of "hold" is also retained to some extent in Spanish and Catalan.

Romansh uses, besides igl ha, the form i dat (literally: it gives), calqued from German es gibt.

To have or to be

[edit]Some languages use their equivalent of 'have' as an auxiliary verb to form the compound forms (e. g. French passé composé) of all verbs; others use 'be' for some verbs and 'have' for others.

- 'have' only: Standard Catalan, Spanish, Romanian, Sicilian.

- 'have' and 'be': Occitan, French, Sardinian, Italian, Northern-Italian languages (Piedmontese, Lombard, Ligurian, Venetian, Friulan), Romansh, Central Italian languages (Tuscan, Umbrian, Corsican) some Catalan dialects (although such usage is recessing in those).

In the latter type, the verbs which use 'be' as an auxiliary are unaccusative verbs, that is, intransitive verbs that often show motion not directly initiated by the subject or changes of state, such as 'fall', 'come', 'become'. All other verbs (intransitive unergative verbs and all transitive verbs) use 'have'. For example, in French, J'ai vu or Italian ho visto 'I have seen' vs. Je suis tombé, sono caduto 'I have (lit. am) fallen'. Note, however, the difference between French and Italian in the choice of auxiliary for the verb 'be' itself: Fr. J'ai été 'I have been' with 'have', but Italian sono stato with 'be'. In Southern Italian languages the principles governing auxiliaries can be quite complex, including even differences in persons of the subject. A similar distinction exists in the Germanic languages, which share a language area[citation needed]; German, Dutch, Danish and Icelandic use 'have' and 'be', while English, Norwegian and Swedish use 'have' only (although in modern English, 'be' remains in certain relic phrases: Christ is risen, Joy to the world: the Lord is come).

"Be" is also used for reflexive forms of the verbs, as in French j'ai lavé 'I washed [something]', but je me suis lavé 'I washed myself', Italian ho lavato 'I washed [something]' vs. mi sono lavato 'I washed myself'.

Tuscan uses si forms identical to the 3rd person reflexive in a usage interpreted as 'we' subject, triggering 'be' as auxiliary in compound constructions, with the subject pronoun noi 'we' optional. If the verb employed is one that otherwise selects 'have' as auxiliary, the past participle is unmarked: si è lavorato = abbiamo lavorato 'we (have) worked'. If the verb is one that otherwise selects 'be', the past participle is marked plural: si è arrivati = siamo arrivati 'we (have) arrived'.

| Form ("to sing") | Latin | Nuorese Sardinian | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Languedocien Occitan | Classical Catalan2 | Milanese Lombard | Romanian | Bolognese Emilian | French |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infinitive | cantāre | cantare [kanˈtare̞] |

cantare [kanˈtaːre] |

cantar [kanˈtar] |

cantar [kɐ̃ˈtaɾ] [kɐ̃ˈtaʁ]1 |

cantar [kanˈta] |

cantar [kənˈta] [kanˈtaɾ] |

cantar [kanˈta] |

a cânta [a kɨnˈta] |

cantèr [kaŋˈtɛːr] |

chanter [ʃɑ̃ˈte] |

| Past participle | cantātum | cantatu [kanˈtatu] |

cantato [kanˈtaːto] |

cantado [kanˈtaðo̞] |

cantado [kɐ̃ˈtadu] |

cantat [kanˈtat] |

cantat [kənˈtat] [kanˈtat] |

cantad [kanˈtaː] |

cântat [kɨnˈtat] |

cantè [kaŋˈtɛː] |

chanté [ʃɑ̃ˈte] |

| Gerund | cantandum | cantande [kanˈtande̞] |

cantando [kanˈtando] |

cantando [kanˈtando̞] |

cantando [kɐ̃ˈtɐ̃du] |

cantant [kanˈtan] |

cantant [kənˈtan] [kanˈtant] |

cantand [kanˈtant] |

cântând [kɨnˈtɨnd] |

cantànd [kaŋˈtaŋd] |

chantant [ʃɑ̃ˈtɑ̃] |

| 1SG INDIC | cantō | canto [ˈkanto̞] |

canto [ˈkanto] |

canto [ˈkanto̞] |

canto [ˈkɐ̃tu] |

cante [ˈkante] |

cant [ˈkan] [ˈkant] |

canti [ˈkanti] |

cânt [ˈkɨnt] |

a3 cant [a ˈkaŋt] |

chante [ˈʃɑ̃t] |

| 2SG INDIC | cantās | cantas [ˈkantaza] |

canti [ˈkanti] |

cantas [ˈkantas] |

cantas [ˈkɐ̃tɐʃ] [ˈkɐ̃tɐs] |

cantas [ˈkantɔs] |

cantes [ˈkantəs] [ˈkantes] |

càntet [ˈkantɛt] |

cânți [ˈkɨntsʲ] |

t cant [t ˈkaŋt] |

chantes [ˈʃɑ̃t] |

| 3SG INDIC | cantat | cantat [ˈkantata] |

canta [ˈkanta] |

canta [ˈkanta] |

canta [ˈkɐ̃tɐ] |

canta [ˈkantɔ] |

canta [ˈkantə] [ˈkanta] |

canta [ˈkantɔ] |

cântă [ˈkɨntə] |

al canta [al ˈkaŋtɐ] |

chante [ˈʃɑ̃t] |

| 1PL INDIC | cantāmus | cantamus [kanˈtamuzu] |

cantiamo [kanˈtjaːmo] |

cantamos [kanˈtamo̞s] |

cantamos [kɐ̃ˈtɐmuʃ] [kɐ̃ˈtɐ̃mus] |

cantam [kanˈtam] |

cantam [kənˈtam] [kanˈtam] |

cantom [ˈkantum, kanˈtum] |

cântăm [kɨnˈtəm] |

a cantän [a kaŋˈtɛ̃] |

chantons [ʃɑ̃ˈtɔ̃] |

| 2PL INDIC | cantātis | cantates [kanˈtate̞ze̞] |

cantate [kanˈtaːte] |

cantáis [kanˈtajs] |

cantais [kɐ̃ˈtajʃ] [kɐ̃ˈtajs] |

cantatz [kanˈtats] |

cantau [kənˈtaw] [kanˈtaw] |

cantev [kanˈteː(f)] |

cântați [kɨnˈtatsʲ] |

a cantè [a kaŋˈtɛ:] |

chantez [ʃɑ̃ˈte] |

| 3PL INDIC | cantant | cantant [ˈkantana] |

cantano [ˈkantano] |

cantan [ˈkantan] |

cantam [ˈkɐ̃tɐ̃w̃] |

cantan [ˈkantan] |

canten [ˈkantən] [ˈkanten] |

canten/canta [ˈkantɛn, ˈkantɔ] |

cântă [ˈkɨntə] |

i cànten [i ˈkaŋtɐn] |

chantent [ˈʃɑ̃t] |

| 1SG SBJV | cantem | cante [ˈkante̞] |

canti [ˈkanti] |

cante [ˈkante̞] |

cante [ˈkɐ̃tɨ] [ˈkɐ̃tᶴi] |

cante [ˈkante] |

cant [ˈkan] [ˈkant] |

canta [ˈkantɔ] |

cânt [ˈkɨnt] |

a canta [a ˈkaŋtɐ] |

chante [ˈʃɑ̃t] |

| 2SG SBJV | cantēs | cantes [ˈkante̞ze̞] |

canti [ˈkanti] |

cantes [ˈkante̞s] |

cantes [ˈkɐ̃tɨʃ] [ˈkɐ̃tᶴis] |

cantes [ˈkantes] |

cantes [ˈkantəs] [ˈkantes] |

càntet [ˈkantɛt] |

cânți [ˈkɨntsʲ] |

t cant [t ˈkaŋt] |

chantes [ˈʃɑ̃t] |

| 3SG SBJV | cantet | cantet [ˈkante̞te̞] |

canti [ˈkanti] |

cante [ˈkante̞] |

cante [ˈkɐ̃tɨ] [ˈkɐ̃tᶴi] |

cante [ˈkante] |

cant [ˈkan] [ˈkant] |

canta [ˈkantɔ] |

cânte [ˈkɨnte̞] |

al canta [al ˈkaŋtɐ] |

chante [ˈʃɑ̃t] |

| 1PL SBJV | cantēmus | cantemus [kanˈte̞muzu] |

cantiamo [kanˈtjaːmo] |

cantemos [kanˈte̞mo̞s] |

cantemos [kɐ̃ˈtemuʃ] [kɐ̃ˈtẽmus] |

cantem [kanˈtem] |

cantem [kənˈtəm] [kənˈtɛm] [kanˈtem] |

cantom [ˈkantum, kanˈtum] |

cântăm [kɨnˈtəm] |

a cantaggna [a kɐnˈtaɲɲɐ] |

chantions [ʃɑ̃ˈtjɔ̃] |

| 2PL SBJV | cantētis | cantetis [kanˈte̞tizi] |

cantiate [kanˈtjaːte] |

cantéis [kanˈte̞js] |

canteis [kɐ̃ˈtejʃ] [kɐ̃ˈtejs] |

cantetz [kanˈtets] |

canteu [kənˈtəw] [kənˈtɛw] [kanˈtew] |

cantev [kanˈteː(f)] |

cântați [kɨnˈtatsʲ] |

a cantèdi [a kaŋˈtɛ:di] |

chantiez [ʃɑ̃ˈtje] |

| 3PL SBJV | cantent | cantent [ˈkante̞ne̞] |

cantino [ˈkantino] |

canten [ˈkante̞n] |

cantem [ˈkɐ̃tẽj̃] |

canten [ˈkanten] |

canten [ˈkantən] [ˈkanten] |

canten/canta [ˈkantɛn, ˈkantɔ] |

cânte [ˈkɨnte̞] |

i cànten [i ˈkaŋtɐn] |

chantent [ˈʃɑ̃t] |

| 2SG imperative | cantā | canta [ˈkanta] |

canta [ˈkanta] |

canta [ˈkanta] |

canta [ˈkɐ̃tɐ] |

canta [ˈkantɔ] |

canta [ˈkantə] [ˈkanta] |

canta [ˈkantɔ] |

cântă [ˈkɨntə] |

canta [ˈkaŋtɐ] |

chante [ˈʃɑ̃t] |

| 2PL imperative | cantāte | cantate [kanˈtate̞] |

cantate [kanˈtaːte] |

cantad [kanˈtað] |

cantai [kɐ̃ˈtaj] |

cantatz [kanˈtats] |

cantau [kənˈtaw] [kanˈtaw] |

cantev [kanˈteːn(f)] |

cântați [kɨnˈtatsʲ] |

cantè [kaŋˈtɛ:] |

chantez [ʃɑ̃ˈte] |

| 1 Also [ɾ̥ r̥ ɻ̝̊ x ħ h] are all possible allophones of [ɾ] in this position, as well as deletion of the consonant. 2 Its conjugation model is based according to the classical model dating to the Middle Ages, rather than the modern conjugations used in Catalonia, the Valencian Community or the Balearic Islands, which may differ accordingly. 3 Conjugated verbs in Bolognese require an unstressed subject pronoun cliticized to the verb. Full forms may be used in addition, thus 'you (pl.) eat' can be a magnè or vuèter a magnè, but bare *magnè is ungrammatical. Interrogatives require enclitics, which may not replicate proclitic forms: magnèv? 'are you (pl.) eating?/do you (pl.) eat?'. | |||||||||||

References

[edit]- Boula de Mareüil, Philippe; Romano, Antonio; Evrard, Marc; Alexandre, François (2024). "Cartografia di innovazioni rispetto al latino attraverso un atlante sonoro dell'Europa" (PDF). In Autelli, Erica (ed.). Il patrimonio linguistico storico della Liguria 2 (in Italian). InSedicesimo. pp. 51–62. ISBN 978-8899866792.

- Chambon, Jean-Pierre. 2011. Note sur la diachronie du vocalisme accentué en istriote/istroroman et sur la place de ce groupe de parlers au sein de la branche romane. Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris 106.1: 293-303.

- François, Alexandre (2014), "Trees, Waves and Linkages: Models of Language Diversification" (PDF), in Bowern, Claire; Evans, Bethwyn (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Historical Linguistics, London: Routledge, pp. 161–189, ISBN 978-0-41552-789-7.

- Kalyan, Siva; François, Alexandre (2018), "Freeing the Comparative Method from the tree model: A framework for Historical Glottometry" (PDF), in Kikusawa, Ritsuko; Reid, Laurie (eds.), Let's talk about trees: Tackling Problems in Representing Phylogenic Relationships among Languages, Senri Ethnological Studies, 98, Ōsaka: National Museum of Ethnology, pp. 59–89.

- Italica: Bulletin of the American Association of Teachers of Italian. Vol. 27–29. Menasha, Wisconsin: George Banta Publishing Company. 1950. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- Koutna, Olga (December 31, 1990). "Chapter V. Renaissance: On the History of Classifications in the Romance Language Group". In Niederehe, Hans-Josef; Koerner, E.F.K. (eds.). History and Historiography of Linguistics: Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on the History of the Language Sciences (ICHoLS IV), Trier, 24–28 August 1987. Vol. 1: Antiquitity , [, sic], –17th Century. Amsterdam, the Netherlands / Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 294. ISBN 9027278113. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- Penny, Ralph (2000). Variation and Change in Spanish. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78045-4.

- Wright, Roger (2013). "Periodization". In Maiden, Martin; Smith, John Charles; Ledgeway, Adam (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Romance Languages: Volume 2. pp. 107–124. doi:10.1017/CHO9781139019996. ISBN 978-1-139-01999-6.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Not only is the tree model inadequate to express the relationships between diatopically related varieties, but it may seriously distort the diachronic and synchronic study of language. Some would argue that this model works well within Indo-European linguistics, where the varieties under consideration (all written and therefore partially or fully standardized) are usually well separated in space and time and where the intervening varieties have all vanished without trace, removing any possibility of viewing the Indo-European family as a continuum. However, where the object of study is a series of now-existing varieties or a range of closely related varieties from the past, the tree model is open to a number of grave objections." (Penny 2000: 22).

- ^ "A linkage consists of separate modern languages which are all related and linked together by intersecting layers of innovations; it is a language family whose internal genealogy cannot be represented by any tree." (François 2014:171).

- ^ Bossong, Georg (2016). Ledgeway, Adam; Maiden, Martin (eds.). "The Oxford Guide to the Romance Languages". Oxford Academic. p. 71. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199677108.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-967710-8. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Bossong 2016, p. 71.

- ^ Wright 2013, p. 118-120.

- ^ Sardos etiam, qui non Latii sunt sed Latiis associandi videntur, eiciamus, quoniam soli sine proprio vulgari esse videntur, gramaticam tanquam simie homines imitantes: nam domus nova et dominus meus locuntur. ["As for the Sardinians, who are not Italian but may be associated with Italians for our purposes, out they must go, because they alone seem to lack a vernacular of their own, instead imitating gramatica as apes do humans: for they say domus nova [my house] and dominus meus [my master]." (English translation provided by Dante Online, De Vulgari Eloquentia, I-xi Archived 2021-02-27 at the Wayback Machine)] It is unclear whether this indicates that Sardinian still had a two-case system at the time; modern Sardinian lacks grammatical case.

- ^ "Dante's Peek". Online Etymology Dictionary. 2020. Archived from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- ^ Andreose, Alvise; Renzi, Lorenzo (2013). Maiden, Martin; Smith, John Charles; Ledgeway, Adam (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Romance Languages: Volume 2. p. 332. doi:10.1017/CHO9781139019996. ISBN 978-1-139-01999-6. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bossong 2016, p. 67.

- ^ Ruhlen M. (1987). A guide to the world's languages, Stanford University Press, Stanford.

- ^ Jones, Michael Allan (1990). "Sardinian". In Harris, Martin; Vincent, Nigel (eds.). The Romance Languages. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 314–350. ISBN 978-0-19-520829-0. Archived from the original on 2023-09-18. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ Zampaulo, André (2019). Palatal sound change in the Romance languages: Diachronic and synchronic perspectives. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198807384.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-880738-4.

- ^ Mensching, Guido; Remberg, Eva-Maria (2016). Ledgeway, Adam; Maiden, Martin (eds.). "The Oxford Guide to the Romance Languages". Oxford Academic. p. 270. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199677108.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-967710-8. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Mensching, Guido; Remberg, Eva-Maria (2016). Ledgeway, Adam; Maiden, Martin (eds.). "The Oxford Guide to the Romance Languages". Oxford Academic. p. 272. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199677108.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-967710-8. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Kabatek, Johannes; Pusch, Claus D. (2011-07-27), 4 The Romance languages, De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 69–96, doi:10.1515/9783110220261.69, ISBN 978-3-11-022026-1, retrieved 2024-03-31

- ^ Beninca, Paola; Parry, Mair; Pescarini, Diego (2016). Ledgeway, Adam; Maiden, Martin (eds.). "The Oxford Guide to the Romance Languages". Oxford Academic. p. 188. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199677108.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-967710-8. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Wright 2013, p. 117-121.

- ^ Craddock, Jerry R. (2002). "Mozarabic Language". In Gerli, E. Michael; Armistead, Samuel G. (eds.). Medieval Iberia: An Encyclopedia. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315161594. ISBN 978-0415939188. OCLC 50404104.

- ^ Barahona, Omar (2015). "The Chronology of Romance Lenition". universiteitleiden.nl. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Jaberg, Karl and Jud, Jakob, Sprach- und Sachatlas Italiens und der Südschweiz, Vol.1–8, Bern: Zofingen, 1928–1940; Karte 1045: QUELLA VACCA, Karte 342: UNA NOTTE (Online access: [1] Archived 2016-12-11 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Kalyan & François (2018)

- ^ See Italica 1950: 46 (cf. [2] and [3]): "Pei, Mario A. "A New Methodology for Romance Classification." Word, v, 2 (Aug. 1949), 135–146. Demonstrates a comparative statistical method for determining the extent of change from the Latin for the free and checked accented vowels of French, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Rumanian, Old Provençal, and Logudorese Sardinian. By assigning 3½ change points per vowel (with 2 points for diphthongization, 1 point for modification in vowel quantity, ½ point for changes due to nasalization, palatalization or umlaut, and −½ point for failure to effect a normal change), there is a maximum of 77 change points for free and checked stressed vowel sounds (11×2×3½=77). According to this system (illustrated by seven charts at the end of the article), the percentage of change is greatest in French (44%) and least in Italian (12%) and Sardinian (8%). Prof. Pei suggests that this statistical method be extended not only to all other phonological, but also to all morphological and syntactical, phenomena.".

- ^ See Koutna et al. (1990: 294): "In the late forties and in the fifties some new proposals for classification of the Romance languages appeared. A statistical method attempting to evaluate the evidence quantitatively was developed in order to provide not only a classification, but at the same time a measure of the divergence among the languages. The earliest attempt was made in 1949 by Mario Pei (1901–1978), who measured the divergence of seven modern Romance languages from Classical Latin, taking as his criterion the evolution of stressed vowels. Pei's results do not show the degree of contemporary divergence among the languages from each other but only the divergence of each one from Classical Latin. The closest language turned out to be Sardinian with 8% then followed Italian — 12%; Spanish — 20%; Romanian — 23,5%; Provençal — 25%; Portuguese — 31%; French — 44%."

- ^ Pei, Mario (1949). "A New Methodology for Romance Classification". WORD. 5 (2): 135–146. doi:10.1080/00437956.1949.11659494.

- ^ Catalan plurals sometimes also involve a change in vowel (la festa / les festes). This is a secondary development, only found in the feminine; Catalan clearly belongs to the first set of languages, those in which plurals are formed by /s/, based on the Latin accusative.

- ^ Entry nulla in Vocabolario Treccani (in Italian)

- ^ a b R. Zanuttini, Negazione e concordanza negativa in italiano e in piemontese[permanent dead link] (in Italian)

- ^ Entry nada in Diccionario de la lengua española (in Spanish)

- ^ Entry rien in CNTRL (in French)

- ^ Entry res in diccionari.cat Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine (in Catalan)

- ^ Entry niente in Vocabolario Treccani (in Italian)

- ^ Entry néant in CNRTL (in French)

- ^ See p.42 of: Metzeltin, Michael (2004). Las lenguas románicas estándar: historia de su formación y de su uso. Llibrería llingüística. Uvieú: Academia de la Llingua Asturiana. ISBN 978-84-8168-356-1.

- ^ See p.341 of: Ledgeway, Adam (2012). From Latin to romance: morphosyntactic typology and change. Oxford studies in diachronic and historical linguistics. Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958437-6.

- ^ Pountain, Christopher J. 1985. Copulas, verbs of possession and auxiliaries in Old Spanish: The evidence for structurally interdependent changes. Bulletin of Hispanic Studies (Liverpool); Liverpool Vol. 62, N° 4, (Oct 1, 1985): 337.

- ^ Existential statements in Neapolitan make use of verb stare.

KSF

KSF