Coldwater Beds

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 8 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 8 min

| Coldwater Beds | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Ypresian (Wasatchian) ~ | |

| Type | Formation |

| Unit of | Kamloops Group |

| Sub-units | Merritt & Quilchena coal basins |

| Overlies | Nicola Group |

| Thickness | 230 m (750 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Mudstone |

| Other | Shale, tuff, coal |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 50°06′N 120°30′W / 50.1°N 120.5°W |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 54°48′N 103°30′W / 54.8°N 103.5°W |

| Region | British Columbia |

| Country | |

| Extent | Okanagan Highlands |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Coldwater River |

| Named by | Dawson |

| Year defined | 1895 |

The Coldwater Beds are a geologic formation of the Okanagan Highlands in British Columbia, Canada. They preserve fossils dating back to the Ypresian stage of the Eocene period, or Wasatchian in the NALMA classification.[1]

The formation comprises mudstones, shales and tuffs deposited in a lacustrine environment and has provided many insect fossils, as well as indeterminate birds and fossil flora.[2]

Description

[edit]The Coldwater Beds were defined by Dawson (1895) based on a section along the Coldwater River in the Okanagan Highlands.[3] The formation reaches a thickness of 230 metres (750 ft),[4] and comprises mudstones, shales and tuff deposited in a lacustrine environment. U-Pb dating of thick tephra, combined with Ar-Ar dates of sanidine from same bed provided an Early Eocene age. The tephra was deposited within insect-bearing shales.[1]

Climate

[edit]

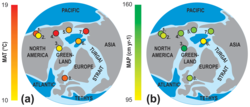

During the Early Eocene, the climate of much of northern North America was warm and wet, with mean annual temperatures (MAT) as high as 20 °C (68 °F), mean annual precipitation (MAP) of 100 to 150 centimetres (39 to 59 in), mild frost-free winters (coldest month mean temperature >5 °C (41 °F)), and climatic conditions that supported extensive temperate forest ecosystems.[5]

The Quilchena fossil locality is dated to 51.5 ± 0.4 Ma corresponding to the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (EECO), and is reconstructed as the warmest and wettest of the Early Eocene upland sites from the Okanagan Highlands of British Columbia and northern Washington State. Mean annual temperature (MAT) is estimated from leaf margin analysis as 16.2 ± 2.1 °C (61.2 ± 3.8 °F) and 14.6 ± 4.8 °C (58.3 ± 8.6 °F). Using bioclimatic analysis of 45 nearest living relatives, a moist mesothermal climate is indicated (MAT 12.7 to 16.6 °C (54.9 to 61.9 °F); cold month mean temperature (CMMT) 3.5 to 7.9 °C (38.3 to 46.2 °F) and mean annual precipitation (MAP) of 103 to 157 centimetres (41 to 62 in)/yr. Leaf size analysis estimates a mean annual precipitation of 121 ± 39 centimetres (48 ± 15 in).[6]

Fossils

[edit]

(1890 illustration)

(1890 illustration)

(1890 illustration)

(1890 illustration)

(1890 illustration)

A wide variety of fossils occur in the formation, including abundant fish remains, insects, and plants, and rare occurrences of molluscs, ostracods, and birds:[1]

Flora

[edit]Fossil plants were first reported from the Coldwater Beds at the Quilchena site and nearby by Penhallow (1908)[7] with an expanded taxonomic list given by Mathewes et al (2016).[6]

- Pteridophytes

- Ginkgophytes

- Pinophytes

- Abies[6]

- cf Amentotaxus[6]

- Calocedrus[6]

- Chamaecyparis[6]

- Glyptostrobus[6]

- Keteleeria[6]

- Metasequoia[6]

- Picea[6]

- Pinus[6]

- Pseudolarix[6]

- Sequoia[6]

- Taxodium[6]

- Thuja[6]

- Tsuga[6]

- Angiosperms

- Acer[6]

- cf. Aesculus[6]

- †Alnus parvifolia[6]

- †Betula leopoldae[6]

- Bignoniaceae[6]

- †Castaneophyllum[6]

- †Comptonia columbiana[6]

- Cornus [6]

- Corylopsis[6]

- Dipteronia[6]

- cf. Disanthus[6]

- †Eucommia montana[8]

- †Eucommia rolandii[8]

- cf. Exbucklandia[6]

- Fagus[6]

- †Florissantia quilchenensis[9]

- Fraxinus[6]

- Hovenia[6]

- †Joffrea/Nyssidium[6]

- Nyssa[6]

- Pieris[6]

- †Plafkeria[6]

- cf. Pterocarya[6]

- Rhus[6]

- cf. Sambucus[6]

- Sassafras[6]

- Ternstroemia[6]

- cf. Gordonia[6]

- Tilia[6]

- Trochodendron[6]

- †Ulmus okanaganensis[7]

Pollen taxa

[edit]- Ginkgophytes

- Pinophytes

- Angiosperms

Molluscs

[edit]Mark Wilson (1987) noted, without taxonomic identification, that unidentified small bivalves are a component of the Quilchena invertebrate paleofauna.[10]

Insects

[edit]The insect fossils studied by Wilson (1987) showed Bibionidae dominating the paleoentemofauna, at 28% of all specimens examined at that time. An additional 13% of the fossils were other dipterans while up to 41% of all insects still had attached wings. The invertebrates trace fossils included two undescribed species of Trichoptera larval cases and burrowing or tracks in the sediment.[10]

- Blattaria

- Coleoptera

- cf. Amara sp.[11]

- †Buprestis saxigena Scudder, 1879[12][13]

- †Buprestis sepulta Scudder, 1879[12][13]

- †Buprestis tertiaria Scudder, 1879[12][13]

- Carabidae indet.[11]

- †Cercyon? terrigena Scudder, 1879[12]

- Curculionidae indet.[11]

- cf. Erotylidae indet.[11]

- †Nebria paleomelas Scudder, 1879[12]

- Omaliinae indet.[11]

- Pachymerina sp.[6]

- Scarabaeoidea indet.[11]

- Dermaptera

- Diptera

- Plecia angustipennis[14]

- Plecia canadensis[14]

- Plecia pictipennis[15]

- Mycetophilidae indet.[11]

- Pipunculidae indet.[11]

- Pipunculinae indet.[16]

- Pleciinae indet.[11]

- Syrphidae indet.[11]

- Tipulidae indet.[11]

- Hemiptera

- Telmatrechus defunctus[15]

- Aphididae indet.[11]

- Cercopoidea indet.[11]

- Cicadellidae indet.[11]

- Cydnidae indet.[11]

- Gerridae indet.[11]

- Megymeninae indet.[11][6]

- cf. Pentatomidae indet.[11]

- Hymenoptera

- Eosphecium naumanni[17]

- Halictus? savenyei[18]

- Braconidae indet.[19]

- Formicidae indet.[11]

- Ichneumonidae indet.[11]

- Tenthredinidae indet.[19]

- Trigonalidae indet.[19]

- Vespidae indet.[11]

- Mecoptera

- Neuroptera

- Polystoechotites sp.[21]

- Palaeopsychops dodgeorum[22]

- Palaeopsychops douglasae[21]

- Wesmaelius mathewesi[23]

- Orthoptera

- Trichoptera

Fish

[edit]- Amia sp. scales[6]

- Amyzon brevipinne[6]

Birds

[edit]- Aves indet. feathers[6][24]

Mammals

[edit]Correlations

[edit]

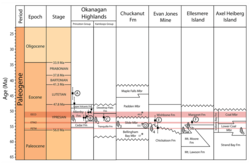

The formation has been correlated with the Eocene Okanagan Highlands floras including the Allenby Formation, Kamloops Group, Horsefly shales, and Driftwood Canyon site of British Columbia, along with the Klondike Mountain Formation of Washington State.[5] Additionally its correlated with the Margaret Formation of Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, the Chickaloon Formation of Alaska, Wishbone, Chuckanut and Iceberg Bay Formations, all of similar age.[5] The flora of the Coldwater Beds has been correlated to the Chu Chua Formation of southeastern British Columbia.[7] The formation also correlates with the Springbrook, Kettle River and O'Brien Creek Formations in Washington, United States.[3]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Coldwater Beds at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Quilchena at Fossilworks.org

- ^ a b Pearson, R. C.; Obradovich, D. (1977). "Eocene Rocks in Northeast Washington- Radiometric Ages and Correlation". United States Geological Survey Bulletin. 1433: 9–10.

- ^ Tribe, Selina (2004). Cenozoic Drainage History of Southern British Columbia - PhD thesis. Simon Fraser University. pp. 41, 67, 112.

- ^ a b c West, Christopher K.; Greenwood, David R.; Reichgelt, Tammo; Lowe, Alexander J.; Vachon, Janelle M.; Basinger, James F. (2020), "Paleobotanical proxies for early Eocene climates and ecosystems in northern North America from middle to high latitudes", Climate of the Past, 16 (4): 1387, 1390–1391, Bibcode:2020CliPa..16.1387W, doi:10.5194/cp-16-1387-2020, retrieved 2020-09-05

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn Mathewes, R. W.; Greenwood, D. R.; Archibald, S. B. (2016). "Paleoenvironment of the Quilchena flora, British Columbia, during the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 53 (6): 574–590. Bibcode:2016CaJES..53..574M. doi:10.1139/cjes-2015-0163. hdl:1807/71979.

- ^ a b c d Greenwood, David R.; Pigg, Kathleen B.; Basinger, James F.; DeVore, Melanie L. (2015). "A review of paleobotanical studies of the Early Eocene Okanagan Highlands floras of British Columbia, Canada and Washington, USA". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences: 15, 18–19.

- ^ a b Call, V.B.; Dilcher, D.L. (1997). "The fossil record of Eucommia (Eucommiaceae) in North America". American Journal of Botany. 84 (6): 798–814. doi:10.2307/2445816. JSTOR 2445816. PMID 21708632. S2CID 20464075.

- ^ Manchester, S. R (1992). "Flowers, fruits, and pollen of Florissantia, an extinct Malvalean genus from the Eocene and Oligocene of western North America". American Journal of Botany. 79 (9): 996–1008. doi:10.1002/j.1537-2197.1992.tb13689.x.

- ^ a b Wilson, M. (1987). "Predation as a source of fish fossils in Eocene lake sediments". PALAIOS. 2 (5): 497–500. Bibcode:1987Palai...2..497W. doi:10.2307/3514620. JSTOR 3514620.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Archibald, S. B.; Mathewes, R. W. (2000). "Early Eocene insects from Quilchena, British Columbia, and their paleoclimatic implications". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 78 (8): 1441–1462. doi:10.1139/z00-070.

- ^ a b c d e Scudder, S. H (1879). "Appendix A. The fossil insects collected in 1877, by Mr. G.M. Dawson, in the interior of British Columbia". Geological Survey of Canada, Report of Progress for. 1877–1878: 175–185.

- ^ a b c Scudder, S. H (1895). "Canadian fossil insects, myriapods and arachnids, Vol II. The Coleoptera hitherto found fossil in Canada". Geological Survey of Canada Contributions to Canadian Palaeontology. 2: 5–26.

- ^ a b Rice, H. M. A (1959). "Fossil Bibionidae (Diptera) from British Columbia". Geological Survey of Canada Bulletin. 55: 1–36.

- ^ a b Handlirsch, A (1910). "Canadian fossil Insects. 5. Insects from the Tertiary lake deposits of the southern interior of British Columbia, collected by Mr. Lawrence M. Lambe". Contributions to Canadian Palaeontology. 2: 93–129.

- ^ Archibald, S. B.; Kehlmaier, C.; Mathewes, R. W. (2014). "Early Eocene big headed flies (Diptera: Pipunculidae) from the Okanagan Highlands, western North America". The Canadian Entomologist. 146 (4): 429–443. doi:10.4039/tce.2013.79. S2CID 55738600.

- ^ Pulawski, W. J.; Rasnitsyn, A. P.; Brothers, D. J.; Archibald, S. B. (2000). "New genera of Angarosphecinae: Cretosphecium from Early Cretaceous of Mongolia and Eosphecium from Early Eocene of Canada (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae)". Journal of Hymenoptera Research. 9: 34–40.

- ^ Engel, M. S.; Archibald, S. B. (2003). "An Early Eocene bee (Hymenoptera: Halictidae) from Quilchena, British Columbia". The Canadian Entomologist. 135: 63–69. doi:10.4039/n02-030. hdl:1808/16473. S2CID 54053341.

- ^ a b c Archibald, S. B.; Rasnitsyn, A. P.; Brothers, D. J.; Mathewes, R. W. (2018). "Modernisation of the Hymenoptera: ants, bees, wasps, and sawflies of the early Eocene Okanagan Highlands of western North America". The Canadian Entomologist. 150 (2): 250–257. doi:10.4039/tce.2017.59. S2CID 90017208.

- ^ a b Archibald, S. B.; Mathewes, R. W.; Greenwood, D. R. (2013). "The Eocene apex of panorpoid scorpionfly family diversity". Journal of Paleontology. 87 (4): 677–695. Bibcode:2013JPal...87..677A. doi:10.1666/12-129. S2CID 88292018.

- ^ a b Archibald, S. B.; Makarkin, V. N. (2006). "Tertiary Giant Lacewings (Neuroptera: Polystoechotidae): revision and description of new taxa from Western North America and Denmark". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 4 (2): 119–155. Bibcode:2006JSPal...4..119A. doi:10.1017/S1477201906001817. S2CID 55970660.

- ^ Makarkin, V. N.; Archibald, S. B. (2003). "Family affinity of the genus Palaeopsychops Andersen with description of a new species from the Early Eocene of British Columbia, Canada (Neuroptera: Polystoechotidae)". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 96 (3): 171–180. doi:10.1603/0013-8746(2003)096[0171:FAOTGP]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 84362010.

- ^ Makarkin, V. N.; Archibald, S. B.; Oswald, J. D. (2003). "New Early Eocene brown lacewings (Neuroptera: Hemerobiidae) from western North America". The Canadian Entomologist. 135 (5): 637–653. doi:10.4039/n02-122. S2CID 53479449.

- ^ Mayr, G.; Archibald, S.B.; Kaiser, G.W.; Mathewes, R.W. (2019). "Early Eocene (Ypresian) birds from the Okanagan Highlands, British Columbia (Canada) and Washington State (USA)". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 56 (8): 803–813. Bibcode:2019CaJES..56..803M. doi:10.1139/cjes-2018-0267. S2CID 135271937.

KSF

KSF