Collaboratory

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A collaboratory, as defined by William Wulf in 1989, is a “center without walls, in which the nation’s researchers can perform their research without regard to physical location, interacting with colleagues, accessing instrumentation, sharing data and computational resources, [and] accessing information in digital libraries” (Wulf, 1989).

Bly (1998) refines the definition to “a system which combines the interests of the scientific community at large with those of the computer science and engineering community to create integrated, tool-oriented computing and communication systems to support scientific collaboration” (Bly, 1998, p. 31).

Rosenberg (1991) considers a collaboratory as being an experimental and empirical research environment in which scientists work and communicate with each other to design systems, participate in collaborative science, and conduct experiments to evaluate and improve systems.

A simplified form of these definitions would describe the collaboratory as being an environment where participants make use of computing and communication technologies to access shared instruments and data, as well as to communicate with others.

However, a wide-ranging definition is provided by Cogburn (2003) who states that “a collaboratory is more than an elaborate collection of information and communications technologies; it is a new networked organizational form that also includes social processes; collaboration techniques; formal and informal communication; and agreement on norms, principles, values, and rules” (Cogburn, 2003, p. 86).

This concept has a lot in common with the notions of Interlock research, Information Routing Group and Interlock diagrams introduced in 1984.

Other meaning

[edit]The word “collaboratory” is also used to describe an open space, creative process where a group of people work together to generate solutions to complex problems.[1]

This meaning of the word originates from the visioning work of a large group of people – including scholars, artists, consultant, students, activists, and other professionals – who worked together on the 50+20 initiative[2] aiming at transforming management education.

In this context, by fusing two elements, “collaboration” and “laboratory”, the word “collaboratory” suggests the construction of a space where people explore collaborative innovations. It is, as defined by Dr. Katrin Muff,[3] “an open space for all stakeholders where action learning and action research join forces, and students, educators, and researchers work with members of all facets of society to address current dilemmas.”

The concept of the collaboratory as a creative group process and its application are further developed in the book “The Collaboratory: A co-creative stakeholder engagement process for solving complex problems”.[1]

Examples of collaboratory events are provided on the website[4] of the Collaboratory community as well as by Business School Lausanne- a Swiss business school that has adopted the collaboratory method to harness collective intelligence.[5]

Background

[edit]Problems of geographic separation are especially present in large research projects. The time and cost for traveling, the difficulties in keeping contact with other scientists, the control of experimental apparatus, the distribution of information, and the large number of participants in a research project are just a few of the issues researchers are faced with.

Therefore, collaboratories have been put into operation in response to these concerns and restrictions. However, the development and implementation proves to be not so inexpensive. From 1992 to 2000 financial budgets for scientific research and development of collaboratories ranged from US$447,000 to US$10,890,000 and the total use ranged from 17 to 215 users per collaboratory (Sonnenwald, 2003). Particularly higher costs occurred when software packages were not available for purchase and direct integration into the collaboratory or when requirements and expectations were not met.

Chin and Lansing (2004) state that the research and development of scientific collaboratories had, thus far, a tool-centric approach. The main goal was to provide tools for shared access and manipulation of specific software systems or scientific instruments. Such an emphasis on tools was necessary in the early development years of scientific collaboratories due to the lack of basic collaboration tools (e.g. text chat, synchronous audio or videoconferencing) to support rudimentary levels of communication and interaction. Today, however, such tools are available in off-the-shelf software packages such as Microsoft NetMeeting, IBM Lotus Sametime, Mbone Videoconferencing (Chin and Lansing, 2004). Therefore, the design of collaboratories may now move beyond developing general communication mechanisms to evaluating and supporting the very nature of collaboration in the scientific context (Chin & Lansing, 2004).

The evolution of the collaboratory

[edit]As stated in Chapter 4 of the 50+20 [6]"Management Education for the World" book,[7] "the term collaboratory was first introduced in the late 1980s to address problems of geographic separation in large research projects related to travel time and cost, difficulties in keeping contact with other scientists, control of experimental apparatus, distribution of information, and the large number of participants. In their first decade of use, collaboratories were seen as complex and expensive information and communication technology (ICT) solutions supporting 15 to 200 users per project, with budgets ranging from 0.5 to 10 million USD. At that time, collaboratories were designed from an ICT perspective to serve the interests of the scientific community with tool-oriented computing requirements, creating an environment that enabled systems design and participation in collaborative science and experiments.

The introduction of a user-centered approach provided a first evolutionary step in the design philosophy of the collaboratory, allowing rapid prototyping and development circles. Over the past decade the concept of the collaboratory expanded beyond that of an elaborate ICT solution, evolving into a “new networked organizational form that also includes social processes, collaboration techniques, formal and informal communication, and agreement on norms, principles, values, and rules”. The collaboratory shifted from being a tool-centric to a data-centric approach, enabling data sharing beyond a common repository for storing and retrieving shared data sets. These developments have led to the evolution of the collaboratory towards a globally distributed knowledge work that produces intangible goods and services capable of being both developed and distributed around the world using traditional ICT networks.

Initially, the collaboratory was used in scientific research projects with variable degrees of success. In recent years, collaboratory models have been applied to areas beyond scientific research and the national context. The wide acceptance of collaborative technologies in many parts of the world opens promising opportunities for international cooperation in critical areas where societal stakeholders are unable to work out solutions in isolation, providing a platform for large multidisciplinary teams to work on complex global challenges.

The emergence of open-source technology transformed the collaboratory into its next evolution. The term open-source was adopted by a group of people in the free software movement in Palo Alto in 1998 in reaction to the source code release of the Netscape Navigator browser. Beyond providing a pragmatic methodology for free distribution and access to an end product's design and implementation details, open-source represents a paradigm shift in the philosophy of collaboration. The collaboratory has proven to be a viable solution for the creation of a virtual organization. Increasingly, however, there is a need to expand this virtual space into the real world. We propose another paradigm shift, moving the collaboratory beyond its existing ICT framework to a methodology of collaboration beyond the tool- and data-centric approaches, and towards an issue-centered approach that is transdisciplinary in nature."

Characteristics and considerations

[edit]A distinctive characteristic of collaboratories is that they focus on data collection and analysis. Hence the interest to apply collaborative technologies to support data sharing as opposed to tool sharing. Chin and Lansing (2004) explore the shift of collaboratory development from traditional tool-centric approaches to more data-centric ones, to effectively support data sharing. This means more than just providing a common repository for storing and retrieving shared data sets. Collaboration, Chin and Lansing (2004) state, is driven both by the need to share data and to share knowledge about data. Shared data is only useful if sufficient context is provided about the data such that collaborators may comprehend and effectively apply it. It is therefore imperative, according to Chin and Lansing (2004), to know and understand how data sets relate to aspects of overall data space, applications, experiments, projects, and the scientific community, identifying the critical features or properties among which we can mention:

- General data set properties (owner, creation data, size, format);

- Experimental properties (conditions of the scientific experiment that generated that data);

- Data provenance (relationship with previous versions);

- Integration (relationship of data subsets within the full data set);

- Analysis and interpretation (notes, experiences, interpretations, and knowledge produced)

- Scientific organization (scientific classification or hierarchy);

- Task (research task that generated or applies the data set);

- Experimental process (relationship of data and tasks to the overall process);

- User community (application of data set to different users).

Henline (1998) argues that communication about experimental data is another important characteristic of a collaboratory. By focusing attention on the dynamics of information exchange, the study of Zebrafish Information Network Project (Henline, 1998) concluded that the key challenges in creating a collaboratory may be social rather than technical. “A successful system must respect existing social conventions while encouraging the development of analogous mechanisms within the new electronic forum” (Henline, 1998, p. 69). Similar observations were made in the Computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) case study (Cogburn, 2003). The author (Cogburn, 2003) is investigating a collaboratory established for researchers in education and other related domains from United States of America and southern Africa. The main finding was that there have been important intellectual contributions on both sides, although the context was that of a developed country working together with a developing one and there have been social as well as cultural barriers. He further develops the idea that a successful CSCL would need to draw the best lessons learned on both sides in computer-mediated communication (CMC) and computer-supported cooperative work (CSCW).

Sonnenwald (2003) conducted seventeen interviews with scientists and revealed important considerations. Scientists expect a collaboratory to “support their strategic plans; facilitate management of the scientific process; have a positive or neutral impact on scientific outcomes; provide advantages and disadvantages for scientific task execution; and provide personal conveniences when collaborating across distances” (Sonnenwald, 2003, p. 68). Many scientists looked at the collaboratory as means to achieve strategic goals that were organizational and personal in nature. Other scientists anticipated that the scientific process would speed up when they had access to the collaboratory.

Design philosophy

[edit]Finholt (1995), based on the case studies of the Upper Atmospheric Research Collaboratory (UARC) and the Medical Collaboratory, establishes a design philosophy: a collaboratory project must be dedicated to a user-centered design (UCD) approach. This means a commitment to develop software in programming environments that allow rapid prototyping, rapid development cycles (Finholt, 1995). A consequence of the user-centered design in the collaboratory is that the system developers must be able to distinguish when a particular system or modification has positive impact on users’ work practices. An important part of obtaining this understanding is producing an accurate picture of how work is done prior to the introduction of technology. Finholt (1995) explains that behavioral scientists had the task of understanding the actual work settings for which new information technologies were developed. The goal of a user-centered design effort was to inject those observations back into the design process to provide a baseline for evaluating future changes and to illuminate productive directions for prototype development (Finholt, 1995).

A similar viewpoint is expressed by Cogburn (2003) who relates the collaboratory to a globally distributed knowledge work, stating that human-computer interaction (HCI) and user-centered design (UCD) principles are critical for organizations to take advantage of the opportunities of globalization and the emergence of an Information society. He (Cogburn, 2003) refers to distributed knowledge work as being a set of “economic activities that produce intangible goods and services […], capable of being both developed and distributed around the world using the global information and communication networks” (Cogburn, 2003, p. 81). Through the use of these global information and communications networks, organizations are able to take part in globally disarticulated production, which means they can locate their research and development facilities almost anywhere in the world, and engineers can collaborate across time zones, institutions and national boundaries.

Evaluation

[edit]Meeting expectations is a factor that influences adoption of innovations, including scientific collaboratories. Some of the collaboratories implemented thus far have not been entirely successful. The Mathematics and Computer Science Division of Argonne National Laboratory, Waterfall Glen collaboratory (Henline, 1998) is an illustrative example. This collaboratory had its shares of problems. There have been the occasional technical and social disasters, but most importantly it did not meet all of the collaboration and interaction requirements.

The vast majority of the evaluations performed thus far are concentrating mainly on the usage statistics (e.g. total number of members, hours of use, amount of data communicated) or on the immediate role in the production of traditional scientific outcomes (e.g. publications and patents). Sonnenwald (2003), however, argues that we should rather look for longer-term and intangible measures such as new and continued relationship among scientists, and subsequent, longer-term creation of new knowledge.

Regardless of the criteria used for evaluation, we must focus on understanding the expectations and requirements defined for a collaboratory. Without such understanding a collaboratory runs the risk of not being adopted.

Success factors

[edit]Olson, Teasley, Bietz, and Cogburn (2002) ascertain some of the success factors of a collaboratory. They are: collaboration readiness, collaboration infrastructure readiness, and collaboration technology readiness.

Collaboration readiness is the most basic pre-requisite for an effective collaboratory, according to Olson, Teasley, Bietz, and Cogburn (2002). Often the critical component to collaboration readiness is based on the concept of “working together in order to achieve a science goal” (Olson, Teasley, Bietz, & Cogburn, 2002, p. 46). Incentives to collaborate, shared principles of collaboration, and experience with the elements of collaboration are also crucial. Successful interaction between users requires a certain amount of common ground. Interactions require a high degree of trust or negotiation, especially when they involve areas where there is a cultural difference. “Ethical norms tend to be culturally specific, and negotiations about ethical issues require high levels of trust” (Olson, Teasley, Bietz, & Cogburn, 2002, p. 49).

When analyzing the collaboration infrastructure readiness Olson, Teasley, Bietz, and Cogburn (2002) state that modern collaboration tools require adequate infrastructure to operate properly. Many off-the-shelf applications will run effectively only on state-of-the-art workstations. An important piece of the infrastructure is the technical support necessary to ensure version control, to get participants registered, and to recover in case of disaster. Communications cost is another element which can be critical for collaboration infrastructure readiness (Olson, Teasley, Bietz, & Cogburn, 2002). Pricing structures for network connectivity can affect the choices that users will make and therefore have an effect on the collaboratory's final design and implementation.

Collaboration technology readiness, according to Olson, Teasley, Bietz, and Cogburn (2002), refers to the fact that collaboration does not involve only technology and infrastructure, but also requires a considerable investment in training. Thus, it is essential to assess the state of technology readiness in the community to ensure success. If the level is too primitive more training is required to bring the users’ knowledge up-to-date.

Examples

[edit]Biological Sciences Collaboratory

[edit]

A comprehensively described example of a collaboratory, the Biological Sciences Collaboratory (BSC) at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (Chin & Lansing, 2004), enables the sharing and analysis of biological data through metadata capture, electronic laboratory notebooks, data organization views, data provenance tracking, analysis notes, task management, and scientific workflow management. BSC supports various data formats, has data translation capabilities, and can interact and exchange data with other sources (external databases, for example). It offers subscription capabilities (to allow certain individuals to access data) and verification of identities, establishes and manages permissions and privileges, and has data encryption capabilities (to ensure secure data transmission) as part of its security package.

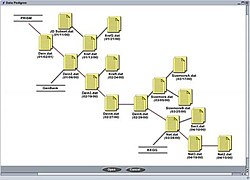

BSC also provides a data provenance tool and a data organization tool. These tools allow a hierarchical tree to display the historical lineage of a data set. From this tree-view the scientist may select a particular node (or an entire branch) to access a specific version of the data set (Chin & Lansing, 2004).

The task management provided by BSC allows users to define and track tasks related to a specific experiment or project. Tasks can have deadlines assigned, levels of priority, and dependencies. Tasks can also be queried and various reports produced. Related to task management, BSC provides workflow management to capture, manage, and supply standard paths of analyses. The scientific workflow may be viewed as process templates that captures and semi-automate the steps of an analysis process and its encompassing data sets and tools (Chin & Lansing, 2004).

BSC provides project collaboration by allowing scientists to define and manage members of their group. Security and authentication mechanisms are therefore applied to limit access to project data and applications. Monitoring capability allows for members to identify other members that are online working on the project (Chin & Lansing, 2004).

BSC offers community collaboration capabilities: scientists may publish their data sets to a larger community through the data portal. Notifications are in place for scientists interested in a particular set of data - when that data changes, the scientists get notification via email (Chin & Lansing, 2004).

Diesel Combustion Collaboratory

[edit]Pancerella, Rahn, and Yang (1999) analyzed the Diesel Combustion Collaboratory (DCC) which was a problem-solving environment for combustion research. The main goal of DCC was to make the information exchange for the combustion researchers more efficient. Researchers would collaborate over the Internet using various DCC tools. These tools included “a distributed execution management system for running combustion models on widely distributed computers (distributed computing), including supercomputers; web accessible data archiving capabilities for sharing graphical experimental or modeling data; electronic notebooks and shared workspaces for facilitating collaboration; visualization of combustion data; and videoconferencing and data conferencing among researchers at remote sites” (Pancerella, Rahn, & Yang, 1999, p. 1).

The collaboratory design team defined the requirements to be (Pancerella, Rahn, & Yang, 1999):

- Ability share graphical data easily;

- Ability to discuss modeling strategies and exchange model descriptions;

- Archiving collaborative information;

- Ability to run combustion models at widely separated locations;

- Ability to analyze experimental data and modeling results in a web-accessible format;

- Videoconference and group meetings capabilities.

Each of these requirements had to be done securely and efficiently across the Internet. Resources availability was a major concern because many of the chemistry simulations could run for hours or even days on high-end workstations and produce Kilobytes to Megabytes of data sets. These data sets had to be visualized using simultaneous 2-D plots of multiple variables (Pancerella, Rahn, & Yang, 1999).

The deployment of the DCC was done in a phased approach. The first phase was based on iterative development, testing, and deployment of individual collaboratory tools. Once collaboratory team members had adequately tested each new tool, it was deployed to combustion researchers. The deployment of the infrastructure (videoconferencing tools, multicast routing capabilities, and data archives) was done in parallel (Pancerella, Rahn, & Yang, 1999). The next phase was to implement full security in the collaboratory. The primary focus was on two-way synchronous and multi-way asynchronous collaborations (Pancerella, Rahn, & Yang, 1999). The challenge was to balance the increased access to data that was needed with the security requirements. The final phase was the broadening of the target research to multiple projects including a broader range of collaborators.

The collaboratory team found that the highest impact was perceived by the geographically separated scientists that truly depended on each other to achieve their goals. One of the team's major challenges was to overcome the technological and social barriers in order to meet all of the objectives (Pancerella, Rahn, & Yang, 1999). User openness and low maintenance security collaboratories are hard to achieve, therefore user feedback and evaluation are constantly required.

Other collaboratories

[edit]Other collaboratories that have been implemented and can be further investigated are:

- Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) is an international center for research and education in biology, biomedicine and ecology.

- Biological Collaborative Research Environment (BioCoRE) developed at University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign – a collaboration tool for biologists (Chin and Lansing, 2004);

- The CTQ Collaboratory, a virtual community of teacher leaders and those who value teacher leadership, run by the Center for Teaching Quality, a national education nonprofit (Berry, Byrd, & Wieder, 2013);

- HASTAC (Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory), founded in 2002 by Cathy N. Davidson, then Vice Provost for Interdisciplinary Studies at Duke University and David Theo Goldberg, Director of the University of California Humanities Research Institute (UCHRI), after contacting scholars across the humanities (including digital humanities), social sciences, media studies, the arts, and technology sectors who shared these convictions and wanted to envision a new kind of organization—an academic social network—that would allow anyone to join and would offer any member of the community to contribute. They began working with a team of developers at Stanford University to code and design a participatory, community site, originally a display website and a Wiki for open contribution and as a community-based publishing and networking platform.

- Molecular Interactive Collaborative Environment (MICE) developed at the San Diego Supercomputer Center – provides collaborative access and manipulation of complex, three-dimensional molecular models as captured in various scientific visualization programs (Chin and Lansing, 2004);

- Molecular Modeling Collaboratory (MMC) developed at University of California, San Francisco – allows remote biologists to share and interactively manipulate three-dimensional molecular models in applications such as drug design and protein engineering (Chin and Lansing, 2004);

- Collaboratory for Microscopic Digital Anatomy (CMDA) – a computational environment to provide biomedical scientists remote access to a specialized research electron microscope (Henline, 1998);

- The Collaboratory for Strategic Partnerships and Applied Research at Messiah College - an organization of Christian students, educators, and professionals affiliated with Messiah College, aspiring to fulfill Biblical mandates to foster justice, empower the poor, reconcile adversaries, and care for the earth, in the context of academic engagement.

- Waterfall Glen – a multi-user object-oriented (MOO) collaboratory at Argonne National Laboratory (Henline, 1998);

- The International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) – a scientific collaboratory for the development of advanced measures of personality and other individual differences (Henline, 1998);

- TANGO – a set of collaborative applications for education and distance learning, command and control, health care, and computer steering (Henline, 1998).

Special consideration should be attributed to TANGO (Henline, 1998) because it is a step forward in implementing collaboratories, as it has distance learning and health care as main domains of operation. Henline (1998) mentions that the collaboratory has been successfully used to implement applications for distance learning, command and control center, telemedical bridge, and a remote consulting tool suite.

- Collaborative architecture and Interactive architecture, the work of Adam Somlai-Fischer and Usman Haque.

- The Internet & Society Collaboratory supported by Google in Germany

Summary

[edit]To date, most collaboratories have been applied largely in scientific research projects, with various degrees of success and failure. Recently, however, collaboratory models have been applied to additional areas of scientific research in both national and international contexts. As a result, a substantial knowledge base has emerged helping us in understanding their development and application in science and industry (Cogburn, 2003). Extending the collaboratory concept to include both social and behavioral research as well as more scientists from the developing world could potentially strengthen the concept and provide opportunities of learning more about the social and technical factors that support a distributed knowledge network (Cogburn, 2003).

The use of collaborative technologies to support geographically distributed scientific research is gaining wide acceptance in many parts of the world. Such collaboratories hold great promise for international cooperation in critical areas of scientific research and not only. As the frontiers of knowledge are pushed back the problems get more and more difficult, often requiring large multidisciplinary teams to make progress. The collaboratory is emerging as a viable solution, using communication and computing technologies to relax the constraints of distance and time, creating an instance of a virtual organization. The collaboratory is both an opportunity with very useful properties, but also a challenge to human organizational practices (Olson, 2002).

See also

[edit]- Information and communication technologies

- Human–computer interaction

- User-centered design

- Participatory design

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b "The Collaboratory".

- ^ "50+20 initiative".

- ^ "Dr.Katrin Muff".

- ^ "Collaboratory community". 9 June 2014.

- ^ "Collaboratory at Business School Lausanne". 8 December 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "50+20 initiative".

- ^ "Management Education for the World". Archived from the original on 2015-08-23. Retrieved 2015-08-21.

References

[edit]- Berry, B., Byrd, A., & Wieder, A. (2013). Teacherpreneurs: Innovative teachers who lead but don't leave. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bly, S. (1998). Special section on collaboratories, Interactions, 5(3), 31, New York: ACM Press.

- Bos, N., Zimmerman, A., Olson, J., Yew, J., Yerkie, J., Dahl, E. and Olson, G. (2007), From Shared Databases to Communities of Practice: A Taxonomy of Collaboratories. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12: 652–672.

- Chin, G., Jr., & Lansing, C. S. (2004). Capturing and supporting contexts for scientific data sharing via the biological sciences collaboratory, Proceedings of the 2004 ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work, 409-418, New York: ACM Press.

- Cogburn, D. L. (2003). HCI in the so-called developing world: what's in it for everyone, Interactions, 10(2), 80-87, New York: ACM Press.

- Cosley, D., Frankowsky, D., Kiesler, S., Terveen, L., & Riedl, J. (2005). How oversight improves member-maintained communities, Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems, 11-20.

- Finholt, T. A. (1995). Evaluation of electronic work: research on collaboratories at the University of Michigan, ACM SIGOIS Bulletin, 16(2), 49–51.

- Finholt, T.A. Collaboratories. (2002). In B. Cronin (Ed.), Annual Review of Information Science and Technology (pp. 74–107), 36. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Information Science.

- Finholt, T.A., & Olson, G.M. (1997). From laboratories to collaboratories: A new organizational form for scientific collaboration. Psychological Science, 8, 28-36.

- Henline, P. (1998). Eight collaboratory summaries, Interactions, 5(3), 66–72, New York: ACM Press.

- Olson, G.M. (2004). Collaboratories. In W.S. Bainbridge (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction. Great Barrington, MA: Berkshire Publishing.

- Olson, G.M., Teasley, S., Bietz, M. J., & Cogburn, D. L. (2002). Collaboratories to support distributed science: the example of international HIV/AIDS research, Proceedings of the 2002 annual research conference of the South African institute of computer scientists and information technologists on enablement through technology, 44–51.

- Olson, G.M., Zimmerman, A., & Bos, N. (Eds.) (2008). Scientific collaboration on the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Pancerella, C.M., Rahn, L. A., Yang, C. L. (1999). The diesel combustion collaboratory: combustion researchers collaborating over the internet, Proceedings of the 1999 ACM/IEEE conference on supercomputing, New York: ACM Press.

- Rosenberg, L. C. (1991). Update on National Science Foundation funding of the “collaboratory”, Communications of the ACM, 34(12), 83, New York: ACM Press.

- Sonnenwald, D.H. (2003). Expectations for a scientific collaboratory: A case study, Proceedings of the 2003 international ACM SIGGROUP conference on supporting group work, 68–74, New York: ACM Press.

- Sonnenwald, D.H., Whitton, M.C., & Maglaughlin, K.L. (2003). Scientific collaboratories: evaluating their potential, Interactions, 10(4), 9–10, New York: ACM Press.

- Wulf, W. (1989, March). The national collaboratory. In Towards a national collaboratory. Unpublished report of a National Science Foundation invitational workshop, Rockefeller University, New York.

- Wulf, W. (1993) The collaboratory opportunity. Science, 261, 854-855.

KSF

KSF