Colpoda

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

| Colpoda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Colpoda inflata | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Clade: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Ciliophora |

| Class: | Colpodea |

| Order: | Colpodida |

| Family: | Colpodidae |

| Genus: | Colpoda O. F. Müller, 1773 |

| Species[1] | |

| |

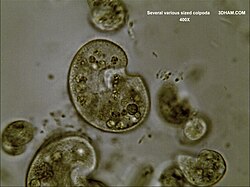

Colpoda is a genus of ciliates in the class Colpodea, order Colpodida, and family Colpodidae.[2]

Description

[edit]Colpoda are distinctly reniform (kidney-shaped) and are strongly convex on one side, and concave on the other. The concave side often looks like a bite was taken out of it. Although they are not as well known as the paramecium, they are often the first protozoa to appear in hay infusions, especially when the sample does not come from an existing mature source of standing water.

Habitat

[edit]

Colpoda are often found in moist soil and because of their ability to readily enter protective cysts will quite frequently be found in desiccated samples of soil and vegetation[3] as well as in temporary natural pools such as tree holes.[4] They have also been found in the intestines of various animals, and can be cultured from their droppings.[5]

Colpoda cucullus has been found inhabiting the surface of plants and seems to dominate the microfauna there. Several species of Colpoda have been found in the pitcher plant Sarracenia purpurea, despite the presence of protease digestive enzymes in the liquid.[6]

Colpoda also tends to be found in abundance where increased levels of bacteria offer an enriched food source. In commercial chicken houses, for example, they seemed to be ubiquitous but the species found vary widely from one location to the next, suggesting that these populations represent local soil and aquatic populations which migrated into the new habitat.[7]

In addition to inhabiting a wide variety of microclimates, Colpoda can be found almost everywhere around the world where there is standing water or moist soil, even where these conditions are only ephemeral. Colpoda brasiliensis for example was discovered in Brazilian floodplains in 2003.[8] Colpoda irregularis has been found in the high desert region of Southwest Idaho. Colpoda aspera has been found in the Antarctic. Colpoda are also found in the arctic where warmer temperatures and longer summers lead to greater density and species diversity.[9]

Not only is the genus widespread, but there are also several species that have nearly global distribution, and, indeed, it has been suggested this may be true of all species, a fact that could be borne out by better investigation.[10] Though Colpoda are not normally found in the marine environment, there are many ways they can travel from one continent to another. For example, cysts can become lodged in the plumage of migratory birds, becoming dislodged hundreds or even thousands of miles away. Also, because cysts are so small and light, they can be swept by air currents into the upper atmosphere, and then come down on another continent.[11]

Reproduction and conjugation

[edit]

Colpoda normally divides into cysts, from which two to eight individuals emerge, four being the most common number. This produces genetically identical individuals. The rate at which such reproduction occurs and how it is affected by various environmental conditions has been the subject of a great deal of scientific research.[12]

On rare occasions, Colpoda have been observed to divide into 4 individuals without producing a cyst wall. It has been suggested that cyst less reproduction was the normal mode of reproduction for Colpoda under optimum conditions and that the formation of cysts was a reaction to adverse environmental conditions. However, the knowledge gained by many years of culturing Colpoda in hay infusions has shown that this mode of reproduction remains rare despite what would seem to be ideal environmental conditions.[13]

As in other ciliates, division in Colpoda may be preceded by a sexual phenomenon known as conjugation. This involves two Colpoda joining at the oral groove and exchanging DNA. Following conjugation, the Colpoda divides, redistributing the DNA of the two original cells to produce numerous genetically distinct offspring.[14][15][16]

Ecological role

[edit]Most Colpoda species are either primarily or exclusively bacterivores feeding on a wide variety of bacteria, which include Moraxella. Several scientific studies have been made on the effect of different bacterial diets on the rate of Colpoda reproduction. Much has been written on the ecological role that Colpoda fulfill in the soil.[17]

In addition to their role as predators of bacteria, Colpoda are themselves prey to a large variety of species. This includes other protozoans as well as small animals such as mosquito larva,[18] other insect larva, and waterfleas.[19]

Uses by humans

[edit]In addition to their use in education and in a wide variety of scientific studies, Colpoda have at times been suggested for more practical uses. Colpoda steini has been suggested as a means to assess the toxicity of soil treated with sewage sludge[20] and as a means to detect chemical contamination in general, possibly in the wake of a terrorist attack.[21]

Species

[edit]- Colpoda acuta - Found in central Europe, it was first described in a paper published in 1977.[22]

- Colpoda aspera - A fairly small species, 12-42 micrometres, noted for being less reniform than other species. Found in Antarctic, Subantarctic [23][24][25]

- Colpoda brasiliensis - A small species, 18-33 micrometres, noted for its mineral envelope which acts as a passive defense against predators. Named for the country in which it was discovered.[26]

- Colpoda californica

- Colpoda cavicola

- Colpoda cucullus - A fairly widespread species noted for being the dominant protozoan on the surface of plants.[27][28]

- Colpoda discoidea

- Colpoda duodenaria - A small to medium-sized species, first described by Charles Vincent Taylor and Waldo Furgason [29] and widely studied for the effects of various chemicals on its excystment process.[30]

- Colpoda ecaudata

- Colpoda elliotti - A small species, 15-28 micrometres, noted as having been cultured from deer droppings.[31]

- Colpoda eurystoma

- Colpoda fastigata

- Colpoda formisanoi

- Colpoda fragilis

- Colpoda henneguyi - Widespread medium to large species, 30-80 micrometres, noted for its habit of staying perfectly still for long periods of time, making it easy to photograph live.[32]

- Colpoda inflata - Possibly one of the best known and most common species, noted for its fitful resting stage in which it jerks around in a tight circle, frustrating microscopists trying to photograph it live.[33][34]

- Colpoda irregularis - This species is noted for a prominent post oral sac and was cultured from moss and soil crust from rocks near desert sagebrush of southwest Idaho.[35]

- Colpoda lucida

- Colpoda magna - A large species, 120-400 micrometres long. Appears dark at lower powers because of dark structures near the contractile vacuole. Often completely packed with food vacuoles.[36]

- Colpoda maupasi - Once thought to be a variety of Colpoda steini, later recognized as a separate species. Classically it was believed to produce only reproductive cysts containing 8 offspring. One strain, however, the Bensonhurst strain, was found to also produce reproductive cysts containing 4 offspring.[37]

- Colpoda ovinucleata

- Colpoda patella

- Colpoda penardi

- Colpoda praestans

- Colpoda quinquecirrata

- Colpoda reniformis

- Colpoda rotunda

- Colpoda simulans - A medium-sized Colpoda with the classic "bite taken out of it" Colpoda shape.[38]

- Colpoda spiralis - A very unusual species with a large overhang that gives it an almost snail-like appearance. It was first found in Arizona [4] and has since been reported in New Mexico and Nevada, with a possible sighting in Northern California.[39]

- Colpoda steini - A widely distributed small to mid-sized species, 14-60 micrometres, usually free living but capable of being parasitic to land slugs.[40]

- Colpoda tripartita

- Colpoda variabili

Videos

[edit]Click on images before playing them to see full size (reload (F5) if you already hit play)

-

several dozen various sized Colpoda representing at least 3 species with other ciliates 100X

-

Large Colpoda amongst many smaller ones with other ciliates 100X

-

Detailed video of Colpoda in resting stage 400X

-

Another view of Colpoda in resting stage, showing relative sizes 400X

-

Unusual Colpoda, possibly Colpoda spiralis 400X

-

Unusual Colpoda, possibly Colpoda spiralis From when it was first spotted.

-

Several colpoda, seemingly stuck to debris 100X

-

Active Colpoda seems to harass a resting Colpoda Magnified 400 times

References

[edit]- ^ Warren, A. (2018). World Ciliophora Database. Colpoda O.F. Müller, 1773. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: http://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=415224 on 2018-08-09

- ^ Lynn, Denis (2008). The Ciliated Protozoa: Characterization, Classification, and Guide to the Literature (3 ed.). Springer Netherlands. pp. 402–3. ISBN 9781402082382.

- ^ "Micscape Microscopy and Microscope Magazine". www.microscopy-uk.org.uk. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Bradbury, P. C.; Outka, D. E. (May 1967). "The Structure of Colpoda elliotti n. sp". The Journal of Protozoology. 14 (2): 344–348. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1967.tb02006.x. ISSN 1550-7408. PMID 4962571.

- ^ biolbull.org [permanent dead link] THE PROTOZOA OF THE PITCHER PLANT, SARRACENIA PURPUREA R W Hegner

- ^ Baré, Julie; Sabbe, Koen; Wichelen, Jeroen Van; Gremberghe, Ineke van; D'hondt, Sofie; Houf, Kurt (March 2009). "Diversity and Habitat Specificity of Free-Living Protozoa in Commercial Poultry Houses". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 75 (5): 1417–1426. Bibcode:2009ApEnM..75.1417B. doi:10.1128/AEM.02346-08. hdl:1854/LU-518994. ISSN 0099-2240. PMC 2648169. PMID 19124593.

- ^ Foissner, W. (January 2003). "Pseudomaryna australiensis nov. gen., nov. spec. and Colpoda brasiliensis nov. spec., two new colpodids (Ciliophora, Colpodea) with a mineral envelope". European Journal of Protistology. 39 (2): 199–212. doi:10.1078/0932-4739-00909. S2CID 83583325.

- ^ H.G. Smith (1973). "The Temperature Regulations and Bi-polar Biogeography of the Ciliate Genus Colpoda" (PDF). British Antarctic Survey Bulletin (37): 7–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ^ Finlay, Bland J.; Esteban, Genoveva F.; Clarke, Ken J.; Olmo, José L. (December 2001). "Biodiversity of Terrestrial Protozoa Appears Homogeneous across Local and Global Spatial Scales". Protist. 152 (4): 355–366. doi:10.1078/1434-4610-00073. PMID 11822663.

- ^ Lynn, Denis (24 June 2008). The Ciliated Protozoa: Characterization, Classification, and Guide to the Literature. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781402082399.

- ^ Cutler, Donald Ward; Crump, Lettice May (January 1924). "The Rate of Reproduction in Artificial Culture of Colpidium colpoda. Part III". Biochemical Journal. 18 (5): 905–912. doi:10.1042/bj0180905. ISSN 0264-6021. PMC 1259465. PMID 16743371.

- ^ Stuart, C. A.; Kidder, G. W.; Griffin, A. M. (December 1939). "Growth Studies on Ciliates. III. Experimental Alteration of the Method of Reproduction in Colpoda". Physiological Zoology. 12 (4): 348–362. doi:10.1086/physzool.12.4.30151513. ISSN 0031-935X. JSTOR 30151513. S2CID 87330049.

- ^ The Journal of Experimental Zoology. 34.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)[full citation needed] - ^ "Life History and Ecology of the Ciliata". www.ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ Kidder, George W.; Claff, C. Lloyd (April 1938). "Cytological Investigations of Colpoda cucullus". The Biological Bulletin. 74 (2): 178–197. doi:10.2307/1537753. ISSN 0006-3185. JSTOR 1537753.

- ^ Elsas, Jan D.; Trevors, Jack T.; Wellington, Elizabeth M. H. (11 June 1997). Modern soil microbiology. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780849390340.

- ^ Cochran-Stafira, D. Liane; von Ende, Carl N. (1998). "Integrating Bacteria into Food Webs: Studies Withsarracenia Purpureainquilines". Ecology. 79 (3): 880–898. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[0880:IBIFWS]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 43311560.

- ^ Lynn, Denis (2008). The ciliated protozoa : characterization, classification, and guide to the literature. New York: Springer. pp. 246. ISBN 9781402082399. OCLC 272311632.

- ^ Use of Colpoda steinii to bioassay the toxicity and bioavailability of heavy metals in a long term sewage sludge-treated soil., Campbell, C.D., Warren, A., Cameron, C.M. and Hope, S.J., (1995) British Section of the Society of Protistologists, Annual Meeting, Liverpool, 27–29 March 1995.

- ^ Pozdnyakova, L.I.; Lozitsky, V.P.; Fedchuk, A.S.; Grigorasheva, I.N.; Boshchenko, Y.A.; Gridina, T.L.; Pozdnyakov, S.V. (2006), "Biological Method for the Water, Food, Fodders, and Environment Toxic Chemical Materials Contamination Indication", Medical Treatment of Intoxications and Decontamination of Chemical Agent in the Area of Terrorist Attack, NATO Security Through Science Series, vol. 1, Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 225–230, doi:10.1007/1-4020-4170-5_26, ISBN 978-1402041686

- ^ "Ref ID : 2365". www.nies.go.jp. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ http://data.aad.gov.au/aadc/biodiversity/taxon_profile.cfm?taxon_id=113907 Biodiversity - SCAR EBA program Taxon Profile

- ^ Petz, W.; Foissner, W. (1997) Morphology and infraciliature of some soil ciliates (Protozoa, Ciliophora) from continental Antarctica, with notes on the morphogenesis of Sterkiella histriomuscorum Polar Record 33, Issue 187 307-326pp.

- ^ http://www.eol.org/pages/2915349?category_id=290[permanent dead link] Encyclopedia of Life

- ^ Foissner, W. (2003). "Pseudomaryna australiensis nov. gen., nov. spec. and Colpoda brasiliensis nov. spec., two new colpodids (Ciliophora, Colpodea) with a mineral envelope". European Journal of Protistology. 39 (2): 199–212. doi:10.1078/0932-4739-00909. S2CID 83583325.

- ^ Bamforth, Stuart S. (February 1973). "Population Dynamics of Soil and Vegetation Protozoa". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 13 (1): 171–176. doi:10.1093/icb/13.1.171. ISSN 1540-7063.

- ^ Bailey, Mark J.; Lilley, A. K.; Timms-Wilson, T. M.; Spencer-Phillips, P. T. N. (2006). Microbial Ecology of Aerial Plant Surfaces. CABI. p. 12. ISBN 9781845931780.

- ^ http://books.nap.edu/html/biomems/ctaylor.pdf Biography of Charles Taylor

- ^ http://www.soc.nii.ac.jp/jsproto/journal/jjp37/119-126.pdf Effects of porphyrins on encystment and excystment in ciliated protozoan Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bradbury, P. C.; Outka, D. E. (May 1967). "The Structure of Colpodaelliottin. sp". The Journal of Protozoology. 14 (2): 344–348. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1967.tb02006.x. ISSN 0022-3921. PMID 4962571. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013.

- ^ http://www.eol.org/pages/486915 Archived 22 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopedia of Life

- ^ http://www.eol.org/pages/486913 Archived 7 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine Colpoda inflata Stokes, 1885

- ^ Bhaskaran K, Nadaraja AV, Balakrishnan MV, Haridas A (March 2008). "Dynamics of sustainable grazing fauna and effect on the performance of gas biofilter". J. Biosci. Bioeng. 105 (3): 192–7. doi:10.1263/jbb.105.192. PMID 18397767.

- ^ "micro*scope". mbl.edu. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ http://www.eol.org/pages/2909580[permanent dead link] Encyclopedia of Life

- ^ Padnos, Morton; Jakowska, Sophie; Nigrelli, Ross F. (May 1954). "Morphology and Life History of Colpoda maupasi, Bensonhurst Strain". The Journal of Protozoology. 1 (2): 131–139. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1954.tb00805.x. ISSN 0022-3921. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012.

- ^ http://protist.i.hosei.ac.jp/pdb/images/Ciliophora/Colpoda/simulans.html Protist images

- ^ http://www.3dham.com/colpoda_spiralis/ Colpoda spiralis ? found in Northern California

- ^ Reynolds, Bruce D. (1936). "Colpoda steini, a Facultative Parasite of the Land Slug, Agriolimax agrestis". The Journal of Parasitology. 22 (1): 48–53. doi:10.2307/3271896. JSTOR 3271896.

KSF

KSF