Combined immunodeficiencies

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 6 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 6 min

| Combined immunodeficiencies | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Combined immunity deficiency, CID |

| |

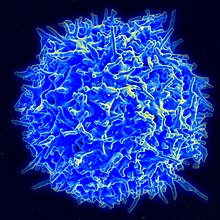

| Scanning electron micrograph of a human T lymphocyte (also called a T cell) from the immune system of a healthy donor. | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

| Symptoms | Diarrhea and sinus infections to opportunistic infections caused by mycobacteria, fungi, and vaccination reactions.[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Complete blood count, absolute neutrophil and lymphocyte count.[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | HIV.[1] |

| Treatment | Immunoglobulin therapy, antimicrobial prophylaxis, and Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.[1] |

| Frequency | 1:100,000 to 1:5000 live births.[2] |

Combined immune deficiencies (CIDs) are a diverse group of inherited immune disorders characterized by impaired T lymphocyte development, function, or both, with variable B cell defects. The primary clinical manifestation of CID is infection susceptibility.[3] Clinical manifestations of combined immunodeficiencies vary greatly, ranging from diarrhea and sinus infections to opportunistic infections caused by mycobacteria, fungi, and vaccination reactions resulting in localized to systemic symptoms.[1]

Antibiotics and immunoglobulin replacement therapy are typically administered to patients as needed. Without hematopoietic cell or other transplantation aimed at correcting the underlying pathophysiological defect, prognosis is frequently poor due to T cell dysfunction.[4]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Patients with combined immune deficiencies typically exhibit recurrent gastrointestinal and respiratory tract infections, which can be attributed to a wide variety of bacteria. However, because of T cell dysfunction, patients frequently struggle to control viral infections, particularly Epstein-Barr virus, which is extremely sensitive to cytolytic T cell dysfunction. Deficits in viral infection control may contribute to an increased likelihood of malignancies, particularly EBV1 lymphoma. Other intracellular microbes, such as mycobacteria, can be difficult to control in CID patients, as can opportunistic or normally non-pathogenic infections caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii or Candida.[4]

Diagnosis

[edit]When a clinical diagnosis of combined immunodeficiency is suspected, preliminary laboratory tests should be ordered. The patient's complete blood count (CBC) reveals immunological changes. The absolute neutrophil and lymphocyte count should be determined based on the patient's age. In all patients, HIV should be ruled out. Specific immunological parameters should be evaluated by measuring immunoglobulins, vaccinal response after 6 months of life, and flow cytometry measurement of larger leukocyte subtypes.[1]

Treatment

[edit]Treatment for combined immunodeficiencies with defects in antibody production primarily consists of immunoglobulin replacement therapy.[1] Susceptibility to infections is an important feature of combined immunodeficiencies and influences patients' clinical evolution; as a result, antimicrobial prophylaxis is frequently used to prevent infections and their complications.[5] For patients with severe and lethal forms of inborn errors of immunity, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation is currently the curative treatment of choice.[1]

Epidemiology

[edit]Globally, the reported incidence of CIDs ranges from 1:100,000 to 1:5000 live births; however, due to patient mortality prior to diagnosis, misdiagnoses of patients exhibiting unusual clinical manifestations, and incomplete national registries recording CID incidence, this is thought to be an underestimate of the true incidence. There has been reported to be a diagnostic delay of a few days to several years between the age at which the disease first manifests and the diagnosis of CID.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Aranda, Carolina Sanchez; Guimarães, Rafaela Rola; de Gouveia-Pereira Pimentel, Mariana (2021). "Combined immunodeficiencies". Jornal de Pediatria. 97. Elsevier BV: S39 – S48. doi:10.1016/j.jped.2020.10.014. ISSN 0021-7557. PMC 9432339.

- ^ a b Chavoshzadeh, Zahra; Darougar, Sepideh; Momen, Tooba; Esmaeilzadeh, Hossein; Abolhassani, Hassan; Cheraghi, Taher; van der Burg, Mirjam; van Zelm, Menno (2021). "Immunodeficiencies affecting cellular and humoral immunity". Inborn Errors of Immunity. Elsevier. p. 9–39. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-821028-4.00010-5. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Yazdani, Reza; Tavakol, Marzieh; Vosughi Motlagh, Ahmad; Shafiei, Alireza; Darougar, Sepideh; Chavoshzadeh, Zahra; Abolhassani, Hassan; Lavin, Martin; Ochs, Hans D. (2021). "Combined immunodeficiencies with associated or syndromic features". Inborn Errors of Immunity. Elsevier. p. 41–91. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-821028-4.00008-7. ISBN 978-0-12-821028-4. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Su, Helen C.; Lenardo, Michael J. (2014). "Combined Immune Deficiencies". Stiehm's Immune Deficiencies. Elsevier. p. 143–169. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-405546-9.00005-4. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Aguilar, C.; Malphettes, M.; Donadieu, J.; Chandesris, O.; Coignard-Biehler, H.; Catherinot, E.; Pellier, I.; Stephan, J.-L.; Le Moing, V.; Barlogis, V.; Suarez, F.; Gerart, S.; Lanternier, F.; Jaccard, A.; Consigny, P.-H.; Moulin, F.; Launay, O.; Lecuit, M.; Hermine, O.; Oksenhendler, E.; Picard, C.; Blanche, S.; Fischer, A.; Mahlaoui, N.; Lortholary, O. (August 14, 2014). "Prevention of Infections During Primary Immunodeficiency". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 59 (10). Oxford University Press (OUP): 1462–1470. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu646. ISSN 1058-4838. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

KSF

KSF