Competition between Airbus and Boeing

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 45 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 45 min

The competition between Airbus and Boeing has been characterized as a duopoly[1] in the large jet airliner market since the 1990s.[2]

The duopoly resulted from a series of mergers within the global aerospace industry, with Airbus beginning as a pan-European consortium while the American Boeing absorbed its former arch-rival, McDonnell Douglas, in 1997. Other manufacturers, such as Lockheed Martin and Convair in the United States, and British Aerospace (now BAE Systems) and Fokker in Europe, were no longer able to compete and effectively withdrew from this market.

In the 10 years from 2007 to 2016, Airbus received orders for 9,985 aircraft and delivered 5,644, while Boeing received orders for 8,978 aircraft and delivered 5,718. During their period of intense competition, both companies regularly accused each other of receiving unfair state aid from their respective governments.

In 2019, Airbus displaced Boeing as the largest aerospace company by revenue due to the Boeing 737 MAX groundings, pulling in revenues of US$78.9 billion and US$76 billion respectively. Boeing recorded $2 billion in operating losses, down from $12 billion profits the previous year, while Airbus profits dropped from $6 billion to $1.5 billion.[3]

Competing products

[edit]Passenger capacity and range comparison

[edit]Airbus and Boeing have wide product ranges, including single-aisle and wide-body aircraft, covering a variety of combinations of capacity and range.

| Type | Length | Span | MTOW | pax | Range | List price[6][7][8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A220-100 | 35.0 m | 35.1 m | 60.8 t | 100–120 | 3,400 nmi (6,300 km) | US$79.5M |

| A220-300 | 38.7 m | 35.1 m | 67.6 t | 120–150 | 3,350 nmi (6,200 km) | US$89.5M |

| A319neo | 33.8 m | 35.8 m | 75.5 t | 120–150 | 3,700 nmi (6,900 km) | US$101.5M |

| 737 MAX-7 | 35.6 m | 35.9 m | 80.3 t | 138–153 | 3,850 nmi (7,130 km) | US$96.0M |

| A320neo | 37.6 m | 35.8 m | 79.0 t | 150–180 | 3,400 nmi (6,300 km) | US$110.6M |

| 737 MAX-8 | 39.5 m | 35.9 m | 82.2 t | 162–178 | 3,550 nmi (6,570 km) | US$117.1M |

| 737 MAX-9 | 42.1 m | 35.9 m | 88.3 t | 178–193 | 3,550 nmi (6,570 km) | US$120.2M |

| 737 MAX-10 | 43.8 m | 35.9 m | 89.8 t | 188–204 | 3,300 nmi (6,100 km) | US$129.9M |

| A321neo | 44.5 m | 35.8 m | 97.0 t | 180–220 | 4,000 nmi (7,400 km) | US$129.5M |

As of 2016, Flight Global fleet forecast 26,860 single aisle deliveries for a $1,360 bn value at a compound annual growth rate of 5% for the 2016–2035 period, with a 45% market share for Airbus (12,090), 43% for Boeing (11,550), 5% for Bombardier Aerospace (1,340), 4% for Comac (1,070) and 3% for Irkut Corporation (810); Airbus predicted 23,531 and Boeing 28,140.[9] Single-aisles generate a vast majority of profits for both, followed by legacy twin aisles like the A330 and B777: Kevin Michaels of AeroDynamic Advisory estimated the B737 to have a 30% profit margin and the B777 classic 20%.[10]

| Type | length | span | MTOW | pax | range | list price[6][7] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 787-8 | 56.7 m | 60.8 m | 228.0 t | 242 | 7,355 nmi (13,621 km) | US$239.0M |

| A330neo-800 | 58.8 m | 64.0 m | 251.0 t | 257 | 8,150 nmi (15,090 km) | US$259.9M |

| A330neo-900 | 63.7 m | 64.0 m | 251.0 t | 287 | 7,200 nmi (13,300 km) | US$296.4M |

| 787-9 | 63.0 m | 60.8 m | 254.0 t | 290 | 7,635 nmi (14,140 km) | US$281.6M |

| A350-900 | 66.8 m | 64.8 m | 283.0 t | 325 | 8,100 nmi (15,000 km) | US$317.4M |

| A350-900 ULR | 66.8 m | 64.8 m | 280.0 t | 325 | 9,700 nmi (18,000 km) | unknown |

| 787-10 | 68.3 m | 60.2 m | 254.0 t | 330 | 6,430 nmi (11,910 km) | US$325.8M |

| 777X-8 | 69.8 m | 71.8 m | 351.5 t | 365 | 8,690 nmi (16,090 km) | US$394.9M |

| A350-1000 | 73.8 m | 64.8 m | 319.0 t | 369 | 8,693 nmi (16,099 km) | US$366.5M |

| 777X-9 | 76.7 m | 71.8 m | 351.5 t | 414 | 7,525 nmi (13,936 km) | US$425.8M |

| 747-8 | 76.3 m | 68.4 m | 447.7 t | 410 | 8,000 nmi (15,000 km) | US$402.9M |

| A380 | 72.7 m | 79.8 m | 575.0 t | 575 | 8,000 nmi (15,000 km) | US$445.6M |

As of 2016, FlightGlobal fleet forecast 7,960 twin aisle deliveries for a $1,284 bn value for the 2016–2035 period.[14] The B787 was predicted to take 31% of the market share, followed by the A350 with 27% and the B777 with 21%, then the A330 and A380 each taking 7%.[15] In June 2017, there were 1,038 orders for Airbus (41%) and 1,514 for Boeing (59%).[16]

| Market | North Atlantic[17] | Trans-pacific[18] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| type | 1H2006 | 1H2016 | 2005 | 2015 |

| A310/DC-10/MD-11 | 3% | 1% | 3% | – |

| A320/737 | 1% | 1% | – | – |

| A330 | 16% | 26% | 3% | 10% |

| A340 | 10% | 6% | 11% | 1% |

| A380 | – | 3% | – | 4% |

| 747 | 15% | 9% | 49% | 10% |

| 757 | 6% | 9% | – | – |

| 767 | 28% | 19% | 7% | 7% |

| 777 | 21% | 20% | 27% | 55% |

| 787 | – | 6% | – | 13% |

Cargo capacity and range comparison

[edit]| Type | length | span | MTOW | capacity | range | list price (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A320P2F[19] | 37.6 m | 35.8 m | 78.0 t | 21.0 t | 2,100 nmi (3,900 km) | converted |

| 737-800BCF[20] | 39.5 m | 79.0 t | 22.7 t | 2,000 nmi (3,700 km) | converted | |

| A321P2F[19] | 44.5 m | 93.5 t | 27.0 t | 1,900 nmi (3,500 km) | converted | |

| 767-300F[20] | 54.9 m | 47.6 m | 186.9 t | 52.5 t | 3,260 nmi (6,040 km) | $203.7M |

| 767-300BCF[20] | 50.9 m | 51.7 t | 3,300 nmi (6,100 km) | converted | ||

| A330-200P2F[21] | 58.8 m | 60.3 m | 233.0 t | 59.0 t | 4,000 nmi (7,400 km) | converted |

| A330-200F[4] | 70.0 t | $237.0M | ||||

| A330-300P2F[21] | 63.7 m | 61.0 t | 3,600 nmi (6,700 km) | converted | ||

| 777F[20] | 64.8 m | 347.8 t | 102.0 t | 4,970 nmi (9,200 km) | $325.7M | |

| A350F[22] | 73.79 m | 64.75 m | 319.0 t | 111.0 t | 5,750 nmi (10,650 km) | $???.?M |

| 747-8F[20] | 76.3 m | 68.4 m | 447.7 t | 137.7 t | 4,120 nmi (7,630 km) | $387.5M |

As Airbus builds only one new freighter, the A330-200F, selling poorly with 42 orders including 38 already delivered, Boeing is almost in a monopoly and can keep producing the 767F and 777F while the 767 and older 777 passenger variants are not selling anymore.[23]

Small single aisles

[edit]In October 2017, Airbus took a 50.01% stake in the Bombardier CSeries programme.[24] In December 2017, Boeing confirmed that it was holding discussions with Embraer for its airliner business.[25] Airbus took control of the CSeries on 1 July 2018 and renamed it Airbus A220.[26] On 5 July 2018, a Boeing-Embraer joint venture was announced for Embraer's airliners, valued at $4.75 billion, for which Boeing was to invest $3.8 billion for an 80% holding.[27] The Embraer E-Jet E2 family competes with the Airbus A220. However, the deal was terminated by Boeing on 24 April 2020.[28]

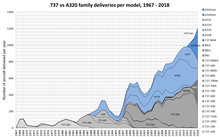

Single aisles: A320 vs 737

[edit]

Airbus sold well the A320 family aircraft to low-cost startups and offering a choice of engines could make them more attractive to airlines and lessors than the single-sourced Boeing 737 family, but CFM engines are extremely reliable. While the 737NG series outsold the A320ceo family since its introduction in 1988, in 2001,[29] and in 2007.[30] the last became the best-selling jet airliner in 2002,[29] and in 2005–2006.[31]

In January 2016, the 737NG series was still lagging around 900 orders with 7,033 against 7,940 of the A320ceo family. For the new re-engined variants, The 737 MAX series had 3,072 orders since its introduction in August 2011 and the A320neo family got 3,355 in the same time frame or in total 4,471 since its launch in December 2010. The six-month head-start of the A320neo allowed Airbus to rack up 1,000 orders.[32] Through August 2016, Airbus had a 59.4% market share of the re-engined single aisle market, while Boeing had 40.6%; Boeing had doubts on over-ordered A320neos by new operators and expected to narrow the gap with potential orders from established airlines.[33] In July 2017, however, Airbus still had sold 1,350 more A320neos than Boeing had sold 737 MAXs.[34] In August 2018, the A321 had outsold the 737-900 three to one, as the A321neo was again dominating the 737-9 MAX, to be joined by the 737-10 MAX.[35] In October 2019, ultimately, the A320 family surpassed the Boeing 737 to become the highest-selling airliner with a total order of 15,193 and respectively 15,136 aircraft at the end of the month.

By July 2021, Airbus (including the A220) had a 65% share of the single-aisle backlog compared to Boeing's 35% share.[36]

In terms of deliveries, as of October 2019, Boeing had shipped 10,563 aircraft of the 737 series since the first delivery to Lufthansa in late 1967, with a further 4,573 on firm order. Airbus had shipped 9,086 A320 family aircraft since the first delivery to Air France in early 1988, with another 6,107 on firm order[37] and for comparison, Boeing delivered 9,037 aircraft within the same time frame.[38][39] To date, with its 21 years ahead of introduction, the 737 series aircraft had been delivered nearly 1,500 more than the A320 family and within the same time frame, the last had 49, slightly more deliveries than its competitor. To increase delivery, Boeing ramped up 737 monthly production from 47 in 2017 to 57 in 2019, whilst Airbus from 46 to 60 and both consider accelerating further despite supplier strain.[40]

By September 2018, there were 7,251 A320ceo family aircraft in service versus 6,757 737NGs, while at the year end there were overall 7,506 A320 family versus 7,310 Boeing 737.

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Twin aisles

[edit]In November 2017, for its chief Willie Walsh, International Airlines Group budget carrier Level benefits more from its two A330-200 lower cost of ownership than its 6t higher fuel burn ($3,500) on a Barcelona-Los Angeles flight: it will introduce three more as there aren't enough B787 pilots.[45] In early 2018, of the 2,673 twin-aisle orders excluding the Airbus A330CEO and quad engine planes (the A380 and B747-8), Boeing had 1,603 (60%) and Airbus 1,070 (40%).[46] By July 2021, Boeing had a 52% share of the widebody backlog compared to 48% for Airbus.[36]

The ultra-long-range variants of new types enable new routes between far away city pairs: the 9,700 nmi Airbus A350-900 ULR entered service in 2018 and the 8,700 to 9,100 nmi (16,100 to 16,900 km) Boeing 777-8 is expected in 2022. Singapore Airlines planned to reintroduce the world's longest flight between Singapore and New York 8,285 nmi (15,344 km) in 2018 with an A350-900 ULR, Qantas hopes to fly from Sydney to New York, which is 8,650 nmi (16,020 km), or Sydney to London, which is 9,200 nmi (17,000 km), within four years for the Project Sunrise, and Air New Zealand wish to operate to the US East Coast, where Auckland and New York are 7,670 nmi (14,200 km) apart.[47] The Singapore-New York A350-900ULR will have a low density premium-focused configuration with only 161 seats: 94 premium economy and 67 business.[48]

Jumbo twin aisles: A380 vs 747

[edit]

During the 1990s both companies researched the feasibility of a passenger aircraft larger than the Boeing 747, which was then the largest airliner in operation. Airbus subsequently launched a full-length double-deck aircraft, the A380, a decade later while Boeing decided the project would not be commercially viable and developed the third generation 747, Boeing 747-8, instead.[49] The Airbus A380 and the Boeing 747-8 are therefore in direct competition on long-haul routes.

Rival performance claims by Airbus and Boeing appear to be contradictory, their methodologies unclear, and neither is validated by a third-party source.[citation needed] Boeing claims the 747-8I to be over 10% lighter per seat and have 11% less fuel consumption per passenger, with a trip-cost reduction of 21% and a seat-mile cost reduction of more than 6%, compared to the A380. The 747-8F's empty weight is expected to be 80 tonnes (88 tons) lower, with 24% less fuel burnt per mass and 21% lower trip costs and 23% lower ton-mile costs than the A380F.[50] On the other hand, Airbus claims the A380 to have 8% less fuel consumption per passenger than the 747-8I and in 2007 Singapore Airlines CEO Chew Choong Seng stated the A380 was performing better than both the airline and Airbus had anticipated, burning 20% less fuel per passenger than the airline's 747-400 fleet.[51] Emirates' Tim Clark also claims that the A380 is more fuel economic at Mach 0.86 than at 0.83.[52] An independent analysis shows a fuel consumption per seat of 3.27 L/100 km for the A380 and 3.35 L/100 km for the B747-8I; a hypothetical re-engined A380neo would have achieved 2.82 to 2.65 L/100 km per seat depending on the options taken.[53]

Airbus emphasises the longer range of the A380 while using up to 17% shorter runways.[54] The A380-800 has 478 square metres (5,150 sq ft) of cabin floor space, 49% more than the 747-8, while commentators noted the "downright eerie" lack of engine noise, with the A380 being 50% quieter than a 747-400 on takeoff.[55] Airbus delivered the 100th A380 on 14 March 2013.[56] From 2012, Airbus was to offer, as an option, a variant with improved maximum take-off weight allowing for better payload/range performance. The precise increase in maximum take-off weight is still unknown. British Airways and Emirates were to be the first customers to take this offer.[57]

As of December 2015, Airbus had 319 orders[58] for the passenger version of the A380 and was not then offering the A380-800 freighter. Production of the A380F was to be suspended until A380 production lines settled; no firm availability date was given.[59] A number of original A380F orders, notably FedEx and the United Parcel Service, were cancelled following delays to the A380 program in October 2006. Some A380 launch customers converted their A380F orders to the passenger version or switched to the 747-8F or 777F aircraft.[60][61]

At Farnborough in July 2016, Airbus announced that in a "prudent, proactive step", starting in 2018, it expected to deliver 12 A380 aircraft per year, down from 27 deliveries in 2015. The firm also warned production might slip back into the red on each aircraft produced at that time, though it anticipated production would remain in the black for 2016 and 2017. The firm expected that healthy demand for its other aircraft would allow it to avoid job losses from the cuts.[62][63]

As of June 2014, Boeing had 51 orders for the 747-8I passenger version and 69 for the 747-8F freighter.[64]

In February 2019, Airbus announced the end of A380 production by 2021, after its main customer, Emirates, dropped an order for 39 of the aircraft. Airbus was to build 17 more A380s before closing the production line, taking the total number of expected deliveries of the aircraft type to 251.[65] At the time, 747 backlog and production rates were sufficient to sustain production until late 2022.[66]

As of 31 January 2020, Boeing had no outstanding unfulfilled orders for the 747-8I passenger version and 17 for the 747-8F freighter;[67] Airbus had 11 A380s remaining to be delivered.[68]

EADS/Northrop Grumman KC-45A vs Boeing KC-767

[edit]The announcement in March 2008 that Boeing had lost a US$40 billion refuelling aircraft contract to Northrop Grumman and Airbus for the EADS/Northrop Grumman KC-45 with the United States Air Force drew angry protests in the United States Congress.[69] Upon review of Boeing's protest, the Government Accountability Office ruled in favour of Boeing and ordered the USAF to recompete the contract. Later, the entire call for aircraft was rescheduled, then cancelled, with a new call decided upon in March 2010 as a fixed-price contract.

Boeing later won the contest against Airbus (Northrop having withdrawn) and US Aerospace/Antonov (disqualified), with a lower price, on 24 February 2011.[70] The price was so low some in the media believe Boeing would take a loss on the deal; they also speculated that the company could perhaps break even with maintenance and spare parts contracts.[71] In July 2011, it was revealed that projected development costs rose $1.4bn and will exceed the $4.9bn contract cap by $300m. For the first $1bn increase (from the award price to the cap), the US government would be responsible for $600m under a 60/40 government/Boeing split. With Boeing being wholly responsible for the additional $300m ceiling breach, Boeing would be responsible for a total of $700m of the additional cost.[72][73][74][clarification needed]

Modes of competition

[edit]Outsourcing

[edit]Because many of the world's airlines are wholly or partially government-owned, aircraft procurement decisions are often taken according to political criteria in addition to commercial ones. Boeing and Airbus seek to exploit this by subcontracting the production of aircraft components or assemblies to manufacturers in countries of strategic importance in order to gain a competitive advantage overall.

For example, Boeing has maintained longstanding relationships since 1974 with Japanese suppliers including Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Kawasaki Heavy Industries by which these companies have had increasing involvement on successive Boeing jet programs, a process which has helped Boeing achieve almost total dominance of the Japanese market for commercial jets. Outsourcing was extended on the 787 to the extent that Boeing's own involvement was reduced to little more than project management, design, assembly, and test operation, outsourcing most of the actual manufacturing all around the world. Boeing has since stated that it "outsourced too much" and that future airplane projects will depend far more on its own engineering and production personnel.[75]

Partly because of its origins as a consortium of European companies, Airbus has had fewer opportunities to outsource significant parts of its production beyond its own European plants. However, in 2009 Airbus opened an assembly plant in Tianjin, China for production of its A320 series airliners,[76] and opened a similar assembly plant in Alabama, United States, in 2015.[77]

Technology

[edit]Airbus sought to compete with the well-established Boeing in the 1970s through its introduction of advanced technology. For example, the A300 made the most extensive use of composite materials yet seen in an aircraft of that era, and by automating the flight engineer's functions, was the first widebody jet to have a two-person flight crew. In the 1980s Airbus was the first to introduce digital fly-by-wire controls into an airliner (the A320).

With Airbus now an established competitor to Boeing, both companies use advanced technology to seek performance advantages in their products. Many of these improvements are about weight reduction and fuel efficiency. For example, the Boeing 787 Dreamliner is the first large airliner to use 50% composites for its construction. The Airbus A350 XWB features 53% composites.[78]

Engine choices

[edit]The competitive strength in the market of any airliner is considerably influenced by the choice of engine available. In general, airlines prefer to have a choice of at least two engines from the major manufacturers General Electric, Rolls-Royce and Pratt & Whitney. However, engine manufacturers prefer to be a single source and often succeed in striking commercial deals with Boeing and Airbus to achieve this.

In 2008, the competition was developing between two sides as Airbus selected the Rolls-Royce Trent XWB alone for the Airbus A350, while GE avoided a $1 billion development competing with its Boeing 777HGW exclusive GE90.[79] In 2013, Boeing rejected a Rolls-Royce engine for the 777X to favor General Electric's GE9X.[80] In 2014, Rolls-Royce secured its exclusivity to power the A330neo with the Trent 7000.[81]

Other aircraft providing a single engine offering include the Boeing 737 MAX (CFM LEAP) or the Airbus A220 (P&W GTF); while those with multiple sources include the Boeing 787 (GEnx/Trent 1000) or the Airbus A320neo (P&W GTF/CFM LEAP).

Currency and exchange rates

[edit]Boeing's production costs are mostly in United States dollars, whereas Airbus's production costs are mostly in euro. When the dollar appreciates against the euro the cost of producing a Boeing aircraft rises relatively to the cost of producing an Airbus aircraft, and conversely when the dollar falls relative to the euro it is an advantage for Boeing. There are also possible currency risks and benefits involved in the way aircraft are sold. Boeing typically prices its aircraft only in dollars, while Airbus, although pricing most aircraft sales in dollars, has been known to be more flexible and has priced some aircraft sales in Asia and the Middle East in multiple currencies. Depending on currency fluctuations between the acceptance of the order and the delivery of the aircraft this can result in an extra profit or extra expense—or, if Airbus has purchased insurance against such fluctuations, an additional cost regardless.[82]

Safety and quality

[edit]Most aircraft dominating the companies' current sales, the Boeing 737-NG and Airbus A320 families and both companies' wide-body offerings, have good safety records. Older model aircraft such as the Boeing 707, Boeing 727, Boeing 737-100/-200, Boeing 747-100/SP/200/300, Airbus A300, and Airbus A310, which were first flown during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, have had higher rates of fatal accidents. Both companies tend to avoid safety comparisons when selling their aircraft to airlines or comparisons on product quality.[83] According to Airbus's John Leahy in 2013, the Boeing 787 Dreamliner battery problems would not cause customers to switch airplane suppliers.[84] The grounding of the Boeing 737 MAX following two high-profile crashes is also unlikely to significantly benefit Airbus at least short-term, as both the 737 MAX and A320neo production lines have backlogs of several years and changing manufacturers requires significant crew training.[85][86]

Aircraft prices

[edit]Airbus and Boeing publish list prices for their aircraft but the actual prices charged to airlines vary; they can be difficult to determine and tend to be much lower than the list prices. Both manufacturers are engaged in a price competition to defend their market share.[87]

The actual transaction prices may be as much as 63% less than the list prices, as reported in 2012 in The Wall Street Journal, giving some examples from the Flight International subsidiary Ascend:[88]

| Model | List price 2012, US$M | Market price | % Discount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boeing 737-800 | 84 | 41 | 51% |

| Boeing 737-900ER | 90 | 45 | 50% |

| Boeing 777-300ER | 298 | 149 | 50% |

| Airbus A319 | 81 | 30 | 63% |

| Airbus A320 | 88 | 40 | 55% |

| Airbus A330-200 | 209 | 84 | 60% |

In May 2013, Forbes magazine reported that the Boeing 787 offered at $225 million was selling at an average of $116m, a 48% discount.[89]

For Ascend's Les Weal, Launch customers obtain good prices on heavier aircraft, lessors are large buyers and benefit too, like airlines as Singapore Airlines or Cathay Pacific since their name gives credibility to a program. In its annual report, Air France cites a €149 million ($195 million) A380, a 52% cut, while in an October 2011 financial release Doric Nimrod Air notes $234 million for its A380 leased to Emirates. Teal group's Richard Aboulafia notes that Boeing's pricing power for the 777-300ER was better when it was alone in its long-haul, large capacity twinjet market but this advantage dissipates with the A350-1000 coming.[90]

For Leeham's Scott Hamilton, small orders are content with 35–40% discount but large airlines sometimes attain 60% and customers with old ties with Boeing like American, Delta or Southwest get a Most-Favoured-Customer Clause guaranteeing them no other customer gets a lower price. Wells Fargo indicates Southwest, the largest 737 customer with 577, got a unit price of $34.7 million for its 737 MAX order of 150 in December 2011, a 64% discount. Ryanair got 53% in September 2001 and claims to obtain at least the same on its last 175 orders. The Airbus-Boeing WTO proceedings indicates EasyJet got a $19,4 million unit price on its A319 order for 120 in 2002, a 56% discount at the time, the same kind of rebate Lion Air got for its A320 order of 234 on 18 March 2013.[90]

Each sale includes an escalation rate covering the workforce and raw material costs increases and as acquisition cost represents 15% of the 20-year total cost of ownership, discussions also include the delivery date, fuel consumption guarantees, financial incentives, maintenance, and training. At Airbus, final price in large campaigns is validated by a committee comprising sales head John Leahy, program director Tom Williams, financial principal Harald Wilhelm and CEO Fabrice Brégier who has the final cut.[90]

Those discounts were presented again in Le Nouvel Observateur's Challenges.fr again with Ascend valuations in 2013:[90]

| Model | List price 2013 | Market price | Discount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boeing 747-8 | 351.4 | 145.0 | 59% |

| Airbus A320-200 | 91.5 | 38.75 | 58% |

| Airbus A330-200 | 239.4 | 99.5 | 58% |

| Boeing 737-800 | 89.1 | 41.8 | 53% |

| Boeing 777-300ER | 315.0 | 152.5 | 52% |

| Airbus A380 | 403.9 | 193.0 | 52% |

| Airbus A320neo | 100.2 | 49.2 | 51% |

| Boeing 737 MAX-8 | 100.5 | 51.4 | 49% |

| Boeing 787-8 | 206.8 | 107.0 | 48% |

| Airbus A350-900 | 287.7 | 152.0 | 47% |

In 2014, Airways News indicated discounted list prices for long haul liners :[91]

| Model | List price 2014 | Market price | Discount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Airbus A330-900 | 275.6 | 124.0 | 55% |

| Airbus A350-900 | 295.2 | 159.4 | 46% |

| Boeing 777-200LR | 296.0 | 118.4 | 60% |

| Boeing 787-9 | 249.5 | 134.7 | 46% |

On 24 December 2014, Transasia Airways announced a commitment to four A330-800s, list price $241.7m, for $480m or $120m each.[92] At the end of 2015, the sale and leaseback of new Airbus A350-900 from GECAS to Finnair value them at €132.5M ($144M)[93]

In order to close the production gap between the B777 classic and the new 777X, Boeing is challenged by a $120m market price for the -300ERs. Competitive pressure from the Bombardier CSeries and E-Jet E2 lead Boeing to pursue the development of the 737 MAX-7 despite low sales,[94] and to sell the Boeing 737-700 at $22m to United Airlines, 27% of the 2015 list price and well below what Embraer or Bombardier could offer for their aircraft.[95]

Moody's Investors Service estimates Delta Air Lines paid $40 million each for its 37 A321ceo order on 29 April 2016, an "end-of-the-line model pricing" of 35% of the $114.9 million list price.[96] Likewise, Air Caraïbes subsidiary French Blue received its A330-300 for $100 million in September 2016.[97]

| Aircraft | List ($m) | Mkt Value ($m) | Discount | Seats | Mkt/Seat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A380 | 432.6 | 236.5 | 45% | 544 | 434743 |

| B777-300ER | 339.6 | 154.8 | 54% | 368 | 420652 |

| A350-900 | 308.1 | 150.0 | 51% | 325 | 461538 |

| B787-9 | 264.6 | 142.8 | 46% | 290 | 492414 |

| B787-8 | 224.6 | 117.1 | 48% | 242 | 483884 |

| A330-300 | 256.4 | 109.5 | 57% | 277 | 395307 |

| A330-200 | 231.5 | 86.6 | 63% | 247 | 350607 |

| A321 | 114.9 | 52.5 | 54% | 185 | 283784 |

| A320neo | 107.3 | 48.5 | 55% | 165 | 293939 |

| B737-900ER | 101.9 | 48.1 | 53% | 174 | 276437 |

| B737-800 | 96.0 | 46.5 | 52% | 160 | 290625 |

| A320 | 98.0 | 44.4 | 55% | 150 | 296000 |

| A319 | 89.6 | 37.3 | 58% | 124 | 300806 |

| B737-700 | 80.6 | 35.3 | 56% | 128 | 275781 |

This appears in the manufacturer's accounting: in their annual reports, Boeing values its 5,700 airliners order book at $416 billion using the contractual prices while Airbus has a backlog of 6,900 worth €1,010 ($1,200) billion at catalog prices, but when updating to more stringent IFRS-15 rules, Credit Suisse estimates it will be revised to €500 billion from 945.[99] Airbus will disclose its backlog value in its 2018 annual report at the latest.[100]

In January 2018, Airbus and Boeing raised their list prices by 2% and 4%, further obscuring pricing transparency as discount levels will rise and with the growing importance of aftermarket services, following the Power by the Hour engine maker model.[101]

In February 2018, Hawaiian Airlines cancelled its order for six Airbus A330-800s to replace them with Boeing 787-9s priced less than $100–115m, close to their production cost of $80–90m, while their normal sales price is around $125m.[102]

By mid 2019, market values are pressured downward by cheap fuel at $2-per-gallon down from $3 in 2011–2014, and low aircraft lease rates reaching less than 0.7% per month while lessors manage 45% of the deliveries. It is exacerbated for Boeing amid the Boeing 737 MAX groundings: the value of a new 737 MAX 8 was reduced by 5% from 49.1 million to $46.7 million, while a new A320neo stays at $49.1 million according to FlightGlobal affiliate Ascend. The A330neo was developed at a fraction of the 787's cost, so Airbus can compete aggressively on price while the A330neo can almost match the 787's performance: Boeing had to discount the dreamliner to win recent deals and 787-9 values eroded from the low-$140 million range to the mid-$130 million range.[103]

Production planning

[edit]Former Airbus executive John Leahy indicated that Airbus has overbooked orders in its backlog, just as Boeing does, and uses internal algorithms to anticipate defections in order to maintain steady production.[104]

Effect of competition on product plans

[edit]The A320 has been selected by 222 operators (Dec. 2008), among these several low-cost operators, gaining ground against the previously well established 737 in this sector; it has also been selected as a replacement for 727s and aging 737s by many full-service airlines such as Star Alliance members United Airlines, Air Canada, and Lufthansa. After dominating the very large aircraft market for four decades, the Boeing 747 faced a challenge from the A380. In response, Boeing offered the stretched and updated 747-8, with greater capacity, fuel efficiency, and range. Frequent delays to the Airbus A380 program caused several customers to consider cancelling their orders in favour of the refreshed 747-8.[105] In February 2019 Airbus announced the end of the A380 production after the remaining orders would be delivered. By June 2019, 154 Boeing 747-8 were ordered and 134 delivered, while 290 Airbus A380 were ordered and 238 delivered.

Boeing pursued and then cancelled several projects, including the Sonic Cruiser. Boeing's current platform for fleet rejuvenation is the Boeing 787 Dreamliner, which uses technology from the Sonic Cruiser concept.

Boeing initially ruled out producing a re-engined version of its 737 to compete with the Airbus A320neo family launch planned for 2015, believing airlines would be looking towards the Boeing Y1 and a 30% fuel saving, instead of paying 10% more for fuel-efficiency gains of only a few percents. Industry sources believe that the 737's design makes re-engining considerably more expensive for Boeing than it was for the Airbus A320. However, there was considerable demand. Southwest Airlines, which uses the 737 for its entire fleet (680 in service or on order), said it was not prepared to wait 20 years or more for a new 737 model and threatened to convert to Airbus.[106] Boeing eventually bowed to airline pressure and in 2011 approved the 737 MAX project, scheduled for first delivery in 2017.

Orders and deliveries

[edit]Orders for and deliveries of Airbus and Boeing aircraft

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Airbus orders

|

Airbus deliveries

|

Boeing orders

|

Boeing deliveries

|

It took Boeing 42 years and 1 month to deliver its 10,000th 7series aircraft (October 1958 – November 2000), and 42 years and 5 months for Airbus to achieve the same milestone (May 1974 – October 2016).[109] Boeing deliveries considerably exceeded that of Airbus throughout the 1980s. In the 1990s, this lead narrowed significantly but Boeing remained ahead of Airbus. In the 2000s, Airbus assumed the lead in narrow-body aircraft. By 2010, little difference remained between Airbus and Boeing in both the wide-body or narrow-body categories or the range on offer.

By July 2021, Airbus had a 62% share of the airliner backlog compared to 38% for Boeing.[36]

Orders and deliveries by year

[edit]The significant orders in a year were +2,094 Airbus aircraft in 2023 and respectively −1026 Boeing aircraft in 2020, while the significant deliveries in a year were 863 Airbus aircraft in 2019 and 4 aircraft in 1974 respectively.

| Boeing[110] | Year | Airbus[111][41] | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deliveries per model | Deliveries | Orders | Orders | Deliveries | Deliveries per model | ||||||||||||||||

| 707 | 717 | 727 | 737 | 747 | 757 | 767 | 777 | 787 | A220 | A300 | A310 | A320 | A330 | A340 | A350 | A380 | |||||

| 21 | 91 | 55 | 22 | 189 | 181 | 1974 | 20 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 7 | 91 | 51 | 21 | 170 | 117 | 1975 | 16 | 8 | 8 | ||||||||||||

| 9 | 61 | 41 | 27 | 138 | 170 | 1976 | 1 | 13 | 13 | ||||||||||||

| 8 | 67 | 25 | 20 | 120 | 228 | 1977 | 16 | 15 | 15 | ||||||||||||

| 13 | 118 | 40 | 32 | 203 | 485 | 1978 | 73 | 15 | 15 | ||||||||||||

| 6 | 136 | 77 | 67 | 286 | 321 | 1979 | 127 | 26 | 26 | ||||||||||||

| 3 | 131 | 92 | 73 | 299 | 374 | 1980 | 47 | 39 | 39 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 94 | 108 | 53 | 257 | 223 | 1981 | 54 | 38 | 38 | ||||||||||||

| 8 | 26 | 95 | 26 | 2 | 20 | 177 | 110 | 1982 | 17 | 46 | 46 | ||||||||||

| 8 | 11 | 82 | 22 | 25 | 55 | 203 | 155 | 1983 | 7 | 36 | 19 | 17 | |||||||||

| 8 | 8 | 67 | 16 | 18 | 29 | 146 | 182 | 1984 | 35 | 48 | 19 | 29 | |||||||||

| 3 | 115 | 24 | 36 | 25 | 203 | 412 | 1985 | 92 | 42 | 16 | 26 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 141 | 35 | 35 | 27 | 242 | 346 | 1986 | 170 | 29 | 10 | 19 | ||||||||||

| 9 | 161 | 23 | 40 | 37 | 270 | 366 | 1987 | 114 | 32 | 11 | 21 | ||||||||||

| 0 | 165 | 24 | 48 | 53 | 290 | 657 | 1988 | 167 | 61 | 17 | 28 | 16 | |||||||||

| 5 | 146 | 45 | 51 | 37 | 284 | 563 | 1989 | 421 | 105 | 24 | 23 | 58 | |||||||||

| 4 | 174 | 70 | 77 | 60 | 385 | 456 | 1990 | 404 | 95 | 19 | 18 | 58 | |||||||||

| 14 | 215 | 64 | 80 | 62 | 435 | 240 | 1991 | 101 | 163 | 25 | 19 | 119 | |||||||||

| 5 | 218 | 61 | 99 | 63 | 446 | 230 | 1992 | 136 | 157 | 22 | 24 | 111 | |||||||||

| 0 | 152 | 56 | 71 | 51 | 330 | 220 | 1993 | 38 | 138 | 22 | 22 | 71 | 1 | 22 | |||||||

| 1 | 121 | 40 | 69 | 41 | 272 | 112 | 1994 | 125 | 123 | 23 | 2 | 64 | 9 | 25 | |||||||

| 89 | 25 | 43 | 37 | 13 | 207 | 379 | 1995 | 106 | 124 | 17 | 2 | 56 | 30 | 19 | |||||||

| 76 | 26 | 42 | 43 | 32 | 219 | 664 | 1996 | 326 | 126 | 14 | 2 | 72 | 10 | 28 | |||||||

| 135 | 39 | 46 | 42 | 59 | 321 | 532 | 1997 | 460 | 182 | 6 | 2 | 127 | 14 | 33 | |||||||

| 282 | 53 | 54 | 47 | 74 | 510 | 606 | 1998 | 556 | 229 | 13 | 1 | 168 | 23 | 24 | |||||||

| 12 | 320 | 47 | 67 | 44 | 83 | 573 | 355 | 1999 | 476 | 294 | 8 | 222 | 44 | 20 | |||||||

| 32 | 282 | 25 | 45 | 44 | 55 | 483 | 588 | 2000 | 520 | 311 | 8 | 241 | 43 | 19 | |||||||

| 49 | 299 | 31 | 45 | 40 | 61 | 525 | 314 | 2001 | 375 | 325 | 11 | 257 | 35 | 22 | |||||||

| 20 | 223 | 27 | 29 | 35 | 47 | 381 | 251 | 2002 | 300 | 303 | 9 | 236 | 42 | 16 | |||||||

| 12 | 173 | 19 | 14 | 24 | 39 | 281 | 239 | 2003 | 284 | 305 | 8 | 233 | 31 | 33 | |||||||

| 12 | 202 | 15 | 11 | 9 | 36 | 285 | 272 | 2004 | 370 | 320 | 12 | 233 | 47 | 28 | |||||||

| 13 | 212 | 13 | 2 | 10 | 40 | 290 | 1002 | 2005 | 1055 | 378 | 9 | 289 | 56 | 24 | |||||||

| 5 | 302 | 14 | 12 | 65 | 398 | 1044 | 2006 | 790 | 434 | 9 | 339 | 62 | 24 | ||||||||

| 330 | 16 | 12 | 83 | 441 | 1413 | 2007 | 1341 | 453 | 6 | 367 | 68 | 11 | 1 | ||||||||

| 290 | 14 | 10 | 61 | 375 | 662 | 2008 | 777 | 483 | 386 | 72 | 13 | 12 | |||||||||

| 372 | 8 | 13 | 88 | 481 | 142 | 2009 | 281 | 498 | 402 | 76 | 10 | 10 | |||||||||

| 376 | 0 | 12 | 74 | 462 | 530 | 2010 | 574 | 510 | 401 | 87 | 4 | 18 | |||||||||

| 372 | 9 | 20 | 73 | 3 | 477 | 805 | 2011 | 1419 | 534 | 421 | 87 | 0 | 26 | ||||||||

| 415 | 31 | 26 | 83 | 46 | 601 | 1203 | 2012 | 833 | 588 | 455 | 101 | 2 | 30 | ||||||||

| 440 | 24 | 21 | 98 | 65 | 648 | 1355 | 2013 | 1503 | 626 | 493 | 108 | 25 | |||||||||

| 485 | 19 | 6 | 99 | 114 | 723 | 1432 | 2014 | 1456 | 629 | 490 | 108 | 1 | 30 | ||||||||

| 495 | 18 | 16 | 98 | 135 | 762 | 768 | 2015 | 1080 | 635 | 491 | 103 | 14 | 27 | ||||||||

| 490 | 9 | 13 | 99 | 137 | 748 | 668 | 2016 | 731 | 688 | 7 | 545 | 66 | 49 | 28 | |||||||

| 529 | 14 | 10 | 74 | 136 | 763 | 912 | 2017 | 1109 | 718 | 17 | 558 | 67 | 78 | 15 | |||||||

| 580 | 6 | 27 | 48 | 145 | 806 | 893 | 2018 | 747 | 800 | 33 | 626 | 49 | 93 | 12 | |||||||

| 127 | 7 | 43 | 45 | 158 | 380 | −87 | 2019 | 768 | 863 | 48 | 642 | 53 | 112 | 8 | |||||||

| 43 | 5 | 30 | 26 | 53 | 157 | −1026 | 2020 | 268 | 566 | 38 | 446 | 19 | 59 | 4 | |||||||

| 263 | 7 | 32 | 24 | 14 | 340 | 479 | 2021 | 507 | 611 | 50 | 483 | 18 | 55 | 5 | |||||||

| 387 | 5 | 33 | 24 | 31 | 480 | 774 | 2022 | 820 | 661 | 53 | 516 | 32 | 60 | ||||||||

| 396 | 1 | 32 | 26 | 73 | 528 | 1314 | 2023 | 2094 | 735 | 68 | 571 | 32 | 64 | ||||||||

| — | — | — | 238 | — | — | 16 | 11 | 40 | 305 | 141 | 2024 | 730 | 559 | 53 | — | — | 444 | 24 | — | 38 | — |

| 1,010 | 155 | 1,831 | 11,898 | 1,573 | 1,049 | 1,319 | 1,738 | 1,150 | 21,688 | Totals until 2024 | 15,756 | 367 | 561 | 255 | 11,707 | 1,615 | 377 | 623 | 251 | ||

| Deliveries per model | Deliveries | Orders | Year | Orders | Deliveries | Deliveries per model | |||||||||||||||

| Boeing | Airbus | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 707 | 717 | 727 | 737 | 747 | 757 | 767 | 777 | 787 | Total Backlog Total

|

A220 | A300 | A310 | A320 | A330 | A340 | A350 | A380 | ||||

| — | — | — | 4,191 | — | — | 88 | 466 | 717 | 5,462 | 31 October 2024 | 31 October 2024 | 8,769 | 545 | — | — | 7,287 | 220 | — | 717 | — | |

The former McDonnell Douglas MD-80, the MD-90 and the MD-11 are included in Boeing deliveries since MD's August 1997 merger with Boeing.

As of January 2024, the manufactures plan to increase the production of their models:[112][a]

- Airbus A220 to 168 per year

- Airbus A320neo family to 900 per year and Boeing 737MAX to 600 per year

- Airbus A330 to 48 per year and Boeing 787 to 120 per year

- Airbus A350 to 108 per year and Boeing 777 to 48 per year

Backlog over time

[edit]This shows the backlog for each year on December 31:[113][114]

| 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airbus | 8,598 | 7,239 | 7,082 | 7,184 | 7,482 | 7,577 | 7,260 | 6,874 | 6,787 | 6,386 | 5,559 | 4,682 | 4,437 | 3,552 | 3,488 | 3,705 | 3,421 | 2,533 | 2,177 | 1,500 | 1,454 | 1,505 | 1,575 | 1,626 |

| Boeing | 5,626 | 4,578 | 4,250 | 4,223 | 5,625 | 5,951 | 5,856 | 5,715 | 5,896 | 5,789 | 5,080 | 4,373 | 3,771 | 3,443 | 3,375 | 3,714 | 3,427 | 2,455 | 1,809 | 1,097 | 1,110 | 1,152 | 1,363 | 1,612 |

| Difference | 2,972 | 2,661 | 2,832 | 2,961 | 1,857 | 1,626 | 1,404 | 1,159 | 891 | 597 | 479 | 309 | 666 | 109 | 113 | 9 | 6 | 78 | 368 | 403 | 344 | 353 | 212 | 14 |

Figures in blue indicate a lead for Airbus. Figures in red indicate a lead for Boeing.

Airliners in service

[edit]| Year/Aircraft | 707 | 717 | 727 | 737 | 747 | 757 | 767 | 777 | 787 | Boeing[115] | A220 | A300 | A310 | A320 | A330 | A340 | A350 | A380 | Airbus | Ratio | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006[116] | 68 | 155 | 620 | 4,328 | 989 | 996 | 862 | 575 | 8,593 | 408 | 199 | 2,761 | 418 | 306 | 4,092 | 2.09:1 | 12,685 | ||||

| 2007[117] | 63 | 155 | 561 | 4,583 | 985 | 1,000 | 880 | 640 | 8,867 | 392 | 193 | 3,095 | 481 | 330 | 4,491 | 1.97:1 | 13,358 | ||||

| 2008[118] | 61 | 154 | 500 | 4,761 | 955 | 980 | 873 | 714 | 8,998 | 387 | 194 | 3,395 | 533 | 330 | 4 | 4,843 | 1.86:1 | 13,841 | |||

| 2009[119] | 58 | 142 | 442 | 4,928 | 947 | 970 | 864 | 780 | 9,131 | 376 | 188 | 3,737 | 607 | 345 | 16 | 5,269 | 1.73:1 | 14,400 | |||

| 2010[120][121] | 39 | 147 | 398 | 5,153 | 915 | 945 | 863 | 858 | 9,318 | 348 | 160 | 4,092 | 675 | 342 | 30 | 5,647 | 1.65:1 | 14,965 | |||

| 2011[122] | 10 | 130 | 250 | 5,177 | 736 | 898 | 837 | 924 | 8,962 | 296 | 121 | 4,392 | 766 | 332 | 50 | 5,957 | 1.50:1 | 14,919 | |||

| 2012[123] | 2 | 143 | 169 | 5,357 | 690 | 860 | 838 | 1,017 | 15 | 9,091 | 262 | 102 | 4,803 | 848 | 312 | 76 | 6,403 | 1.42:1 | 15,494 | ||

| 2013[124] | 148 | 109 | 5,458 | 627 | 855 | 821 | 1,094 | 68 | 9,180 | 234 | 84 | 5,170 | 927 | 298 | 106 | 6,819 | 1.35:1 | 15,999 | |||

| 2014[125][126] | 154 | 87 | 5,782 | 585 | 812 | 795 | 1,188 | 163 | 9,564 | 216 | 71 | 5,632 | 1,020 | 266 | 136 | 7,341 | 1.30:1 | 16,905 | |||

| 2015[127] | 136 | 69 | 6,135 | 571 | 738 | 765 | 1,265 | 286 | 9,965 | 207 | 62 | 6,050 | 1,095 | 227 | 5 | 167 | 7,813 | 1.28:1 | 17,778 | ||

| 2016[128][129] | 154 | 64 | 6,512 | 515 | 688 | 742 | 1,324 | 423 | 10,422 | 210 | 47 | 6,510 | 1,154 | 196 | 29 | 193 | 8,339 | 1.25:1 | 18,761 | ||

| 2017[130][131] | 154 | 57 | 6,864 | 489 | 689 | 744 | 1,387 | 554 | 10,938 | 211 | 37 | 6,965 | 1,214 | 176 | 92 | 212 | 8,907 | 1.23:1 | 19,845 | ||

| 2018[132] | 148 | 44 | 7,310 | 462 | 666 | 742 | 1,416 | 675 | 11,463 | 39 | 212 | 31 | 7,506 | 1,265 | 159 | 185 | 223 | 9,620 | 1.19:1 | 21,083 | |

| 2019[133] | 145 | 40 | 7,132 | 461 | 655 | 729 | 1,424 | 808 | 11,394 | 77 | 202 | 25 | 7,913 | 1,270 | 135 | 282 | 233 | 10,137 | 1.12:1 | 21,531 | |

| 2020[134] | 91 | 34 | 5,743 | 327 | 479 | 544 | 1,041 | 728 | 8,987 | 105 | 185 | 14 | 6,269 | 755 | 59 | 293 | 18 | 7,698 | 1.17:1 | 16,685 | |

| 2023[135][136] | 105 | 36 | 6,500 | 441 | 582 | 269 | 1,163 | 1,113 | 10,208 | 314 | 219 | 52 | 10,562 | 1,469 | 202 | 585 | 233 | 13,636 | 1:1.3 | 23,844 | |

| 707 | 717 | 727 | 737 | 747 | 757 | 767 | 777 | 787 | Total | A220 | A300 | A310 | A320 | A330 | A340 | A350 | A380 | Total |

Controversies

[edit]

Subsidies

[edit]Boeing has continually protested over launch aid in the form of credits to Airbus, while Airbus has argued that Boeing receives illegal subsidies through military and research contracts and tax breaks.[137]

In July 2004, Harry Stonecipher (then CEO of Boeing) accused Airbus of abusing a 1992 bilateral EU-US agreement regarding large civil aircraft support from governments. Airbus is given reimbursable launch investment (RLI, called "launch aid" by the US) from European governments with the money being paid back with interest, plus indefinite royalties if the aircraft is a commercial success.[138] Airbus contends that this system is fully compliant with the 1992 agreement and WTO rules. The agreement allows up to 33 percent of the program cost to be met through government loans which are to be fully repaid within 17 years with interest and royalties. These loans are held at a minimum interest rate equal to the cost of government borrowing plus 0.25%, which would be below market rates available to Airbus without government support.[139] Airbus claims that since the signing of the EU-US agreement in 1992, it has repaid European governments more than US$6.7 billion and that this is 40% more than it has received.

Airbus argues that pork barrel military contracts awarded to Boeing (the second largest US defense contractor) are in effect a form of subsidy (see the KC-X program). The US government support of technology development via NASA also provides support to Boeing. In its recent products such as the 787, Boeing has also received support from local and state governments.[140] Airbus's parent, EADS, is itself a military contractor, paid to develop and build projects such as the Airbus A400M transport and various other military aircraft.[141]

In January 2005, European Union and United States trade representatives Peter Mandelson and Robert Zoellick agreed to talks aimed at resolving increasing tensions. The talks were unsuccessful; the parties did not reach a settlement and the dispute became more acrimonious.

World Trade Organization litigation

[edit]We remain united in our determination that this dispute shall not affect our cooperation on wider bilateral and multilateral trade issues. We have worked together well so far, and intend to continue to do so.

Joint EU-US statement[142]

On 31 May 2005, the United States filed a case against the European Union for providing allegedly illegal subsidies to Airbus. Twenty-four hours later, the European Union filed a complaint against the United States, protesting support for Boeing.[143]

Increased tensions, due to support for the Airbus A380, escalated toward a potential trade war as the launch of the Airbus A350 neared. Airbus preferred launching the A350 program with the help of state loans covering a third of the development costs, although stated that it would launch without these loans if required. The A350 competes with Boeing's most successful project in recent years, the 787 Dreamliner. EU trade officials questioned the nature of the funding provided by NASA, the Department of Defense, and in particular the form of R&D contracts that benefit Boeing; as well as funding from US states such as Washington, Kansas, and Illinois, for the development and launch of Boeing aircraft, in particular, the 787.[144] An interim report of the WTO investigation into the claims made by both sides was made in September 2009.[145]

In March 2010, the WTO ruled that European governments unfairly financed Airbus.[146] In September 2010, a preliminary report of the WTO found unfair Boeing payments broke WTO rules and should be withdrawn.[147] In two separate findings issued in May 2011, the WTO found, firstly, that the US defence budget and NASA research grants could not be used as vehicles to subsidise the civilian aerospace industry and that Boeing must repay $5.3 billion of illegal subsidies.[148] Secondly, the WTO Appellate Body partly overturned an earlier ruling that European Government launch aid constituted unfair subsidy, agreeing with the point of principle that the support was not aimed at boosting exports and some forms of public-private partnership could continue. Part of the $18bn in low interest loans received would have to be repaid eventually; however, there was no immediate need for it to be repaid and the exact value to be repaid would be set at a future date.[149] Both parties claimed victory in what was the world's largest trade dispute.[150][151][152]

On 1 December 2011, Airbus reported that it had fulfilled its obligations under the WTO findings and called upon Boeing to do likewise in the coming year.[153] The United States did not agree and had already begun complaint procedures prior to December, stating the EU had failed to comply with the DSB's recommendations and rulings, and requesting authorisation by the DSB to take countermeasures under Article 22 of the DSU and Article 7.9 of the SCM Agreement. The European Union requested the matter be referred to arbitration under Article 22.6 of the DSU. The DSB agreed that the matter raised by the European Union in its statement at that meeting be referred to arbitration as required by Article 22.6 of the DSU however on 19 January 2012 the US and EU jointly agreed to withdraw their request for arbitration.[154]

On 12 March 2012, the appellate body of the WTO released its findings confirming the illegality of subsidies to Boeing whilst confirming the legality of repayable loans made to Airbus. The WTO stated that Boeing had received at least $5.3 billion in illegal cash subsidies at an estimated cost to Airbus of $45 billion. A further $2 billion in state and local subsidies that Boeing is set to receive have also been declared illegal. Boeing and the US government were given six months to change the way government support for Boeing is handled.[155] At the DSB meeting on 13 April 2012, the United States informed the DSB that it intended to implement the DSB recommendations and rulings in a manner that respects its WTO obligations and within the time-frame established in Article 7.9 of the SCM Agreement. The European Union welcomed the US intention and noted that the 6-month period stipulated in Article 7.9 of the SCM Agreement would expire on 23 September 2012. On 24 April 2012, the European Union and the United States informed the DSB of Agreed Procedures under Articles 21 and 22 of the DSU and Article 7 of the SCM Agreement.[156]

On 25 September 2012, the EU requested discussions with the US, because of the alleged non-compliance of the US and Boeing with the WTO ruling of 12 March 2012. On 27 September 2012, the EU requested the WTO to approve EU countermeasures against the USA's subsidy of Boeing. The WTO approved the creation of a panel to rule on the dispute; this ruling was originally scheduled for 2014 but, because of the complexity of the case, was deferred to be decided not before 2016. The EU wanted permission to place trade sanctions of up to 12 billion US$ annually against the USA. The EU believed this amount represents the damage the illegal subsidies of Boeing cause to the EU.[157][158]

On 19 December 2014, the EU requested WTO mediated consultations with the US over the tax incentives given by the state of Washington to large civil aircraft manufacturers which they believed violated the earlier WTO ruling, on 22 April 2015 at the request of the EU a WTO panel was set up to rule on the complaint.[159] The tax incentives given by the state of Washington and believed to be the largest in US history[160] surpassing the previous record of $5.6bn over 30 years awarded by the state of New York to the aluminum producer Alcoa in 2007. The $8.7bn over 40 years incentive to Boeing to manufacture the 777X in the state includes $4.2bn from a 40% reduction in business taxes, £3.5bn in tax credits for the firm, a $562m tax credit on property and buildings belonging to Boeing, a $242m sales tax exemption for buying computers and $8m to train 1000 workers,[161] Airbus alleges this is larger than the budgeted cost of Boeing's 777X development program and the EU argues amounts to an entire publicly funded free aircraft program for Boeing, the legislation was an extension of the duration of a tax break program given to Boeing for Dreamliner development that had already been ruled illegal by the WTO in 2012.[162] Boeing defends the allegation by arguing the subsidies are available to anyone however for an aircraft to qualify for the tax breaks a company must manufacture aircraft wings and perform all final assembly for an aircraft model or variant exclusively in the state.[163]

In September 2016, the WTO found that Airbus did not remedy the harm to Boeing from illegal subsidies, and the EU immediately appealed for a final decision in late spring 2018. Boeing expected the 2016 decision would largely be upheld with sanctions of $10 to $15 billion, possibly levied by punitive US government tariffs, but that the EU would retaliate strongly. The EU case against Boeing filed as a countersuit lags the US case and the decision on Boeing's appeal will not come out until late in 2018 or even in 2019.[164] Both are exposed with a backlog of 644 Boeing orders in the EU and 1,340 Airbus orders in the US, but this is mitigated as many are from lessors, to be delivered elsewhere, and as Airbus has an assembly line in Alabama.[165]

On 15 May 2018, in its EU appeal ruling, the WTO concluded that the A380 and A350 received improper subsidies through repayable launch aids or low interest rates, like previous airliners, which could have been avoided. Boeing claimed victory but Airbus countered it is thin with 94% of the complaints rejected, as launch aids are legal but at market interest rates, not lower: violations will be corrected. US tariffs, probably on other industries, may take up to 18 months to get WTO approval, but EU could retaliate over Washington State 787 subsidies and tax breaks for the 777X.[166] The US will pursue penalties if an agreement cannot be reached but is willing to reach a settlement with the European Union.[167]

Tariffs

[edit]On 9 April 2019, the US Government announced that it would pursue penalties by placing tariffs on Airbus and other European Union goods over Airbus' improper subsidies, in an apparent act of retaliation. In response, Bruno Le Maire, France's financial minister, said that a "friendly" solution should be made.[168][169][170][171] On 1 July, the US Government proposed more tariffs for the same reason.[172]

On 24 September the same year, it was announced that the WTO would authorize the US to place the tariffs. The WTO stated that the $8 billion USD of EU goods could be affected by the tariffs.[173]

The WTO announced the allowed level of punitive tariffs on 30 September, around $5-10 billion down from the $25 billion asked for, then the USTR should issue a list of products to be taxed from year-end. By mid-2020, the WTO is slated to determine the allowed EU punitive tariffs, as the EU claims $20 billion in damages. It would damage both sides, with Boeing having the most to lose as US Aerospace and defense exports to Europe totals $30.5 billion, while imports are $23.6 billion.[174]

On 2 October 2019, the WTO approved US tariffs on $7.5 billion worth of European goods,[175] and officially authorized them on 14 October, despite the European Union urging for a negotiated settlement.[176][177] After midnight on 18 October, the US tariffs went into effect. The tariffs target Airbus, wine, and other European goods.[178][179]

On 15 February 2020, the US government announced that it would increase tariffs on Airbus aircraft from 10% to 15%. Airbus expressed regret at the statement.[180] The increased tariffs went into effect on 17 February.[181][182] In an attempt to reduce the threat of retaliatory tariffs by the European Union on exports from Washington state, Boeing requested on 19 February that the Washington State Legislature suspend its preferential business-and-occupation tax rate, which saves Boeing around $100 million annually. The WTO ruled in March of the previous year that the tax breaks for Boeing by the state of Washington constituted illegal US subsidies, but determined that, except for the tax break which Boeing requested suspension of, the European Union had no grounds to seek damages.[183]

On 30 September 2020, the WTO approved the European Union's retaliatory tariffs on $4.1 billion worth of US goods, this is in addition to the previous unimplemented sanction allowing the EU the right to impose tariffs of up to $8.2 billion on US goods and services.[184][185][186] On 11 October, acting European Commissioner for Trade Valdis Dombrovskis urged the US to withdraw its tariffs, reiterating retaliatory action.[187] Two days later, on 13 October, the WTO authorized the EU's tariffs.[188] The next day, on 14 October, the US finally offered to remove their tariffs if Airbus would refinance the state loans at a level of interest that assumed a 50% product failure rate. The EU criticized the deal as "unacceptable" due to its cost estimated to be around $10 billion along with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the aviation industry. The US argued that European tariffs on US goods were unnecessary as the local tax subsidies for Boeing had ended while Airbus countered that the US was still applying import tariffs even though the A380 was no longer in production. Further talks with the WTO regarding the tariffs are scheduled for 26 October, however, the tariffs may only go into effect depending on the results on the 2020 United States presidential election.[189][190][191] On 9 November the WTO announced that the EU's tariffs would still go into effect,[192] though the EU indicated it was hopeful a settlement could be reached with the new US administration in 2021.[193][194] On 13 November Bruno Le Maire said a settlement could potentially be reached in several weeks.[195] Both sides resumed negotiations on 2 December.[196] In an attempt to reduce tensions, the United Kingdom dropped its own tariffs on US goods on 8 December.[197]

On 30 December 2020, the US government announced that it would widen its current tariffs on EU goods, it said it was unfair that the duties for the EU sanctions upon the US were calculated during the COVID-19 outbreak when US exports were smaller than usual increasing the number of US goods to which tariffs needed to be applied to reach the WTO's approved sanction value.[198] The widening took effect on 12 January 2021.[199]

On 4 March 2021, the US government suspended its tariffs on UK goods as part of resolving the dispute.[200] The next day, on 5 March, the US and EU both suspended their tariffs on their respective goods for the same reason.[201][202] On 22 March, US trade representative Katherine Tai held a meeting with EU trade commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis and UK trade secretary Liz Truss to begin negotiations to end the dispute.[203]

On 15 June 2021, the US and EU reached a truce, suspending the tariffs for five years.[204] The two sides agreed that future research and development funding would be given out transparently and without advantaging domestic producers.[205]

See also

[edit]- Airbus Corporate Jets

- Boeing Commercial Airplanes

- Competition in the Regional jet market

- List of civil aircraft

Notes

[edit]- ^ Figures regarding Boeing by 2025/26, A220 and A350 by 2025, A320neo family by 2026 and A330 by 2024

References

[edit]- ^ Pfeifer, Sylvia; Georgiadis, Philip; Chávez, Steff (28 January 2024). "How Boeing's troubles are upsetting the balance of power in aviation". The Financial Times. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

'The duopoly is working', says Nick Cunningham at Agency Partners a consultancy in London. 'There is no competition worth talking of yet...'

- ^ Airlines Industry Profile: United States, Datamonitor, November 2008, pp. 13–14

- ^ Murdo Morrison (15 September 2020). "Airbus displaces Boeing as aerospace's biggest company". FlightGlobal.

- ^ a b c "Family figures" (PDF). Airbus. April 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ "737 MAX". Boeing.

- ^ a b "Airbus 2018 Price List" (Press release). Airbus. 15 January 2018. Archived from the original on 16 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ a b "About Boeing Commercial Airplanes: Prices". Boeing.

- ^ "List Prices - Commercial Aircraft". Bombardier Aerospace. January 2017. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018.

- ^ "Flight Fleet Forecast's single-aisle outlook 2016-2035". Flight Global. 16 August 2016.

- ^ "Pontifications: Boeing's long-term message doesn't resonate". Leeham Co. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ "787 by design". Boeing.

- ^ "777X by design". Boeing.

- ^ "747-8". Boeing.

- ^ "Flight Fleet Forecast Summary". Flight Global. 2016.

- ^ "Ascend widebody fleet forecast". Flight Global. 13 October 2016.

- ^ "wide boys". Flight Global. June 2017.

- ^ "747-400 fleet profile: Air France, Cathay Pacific and Saudia retire passenger 747 fleets in 2016". CAPA - Centre for Aviation. 18 January 2016.

- ^ "Singapore Airlines to resume non-stop US services with A350-900ULR: a strategic imperative". CAPA - Centre for Aviation. 15 October 2015.

- ^ a b "EFW, ST Aerospace and Airbus to launch A320/A321P2F freighter conversion programme". Airbus. 17 June 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Freighters". Boeing. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ a b "A330P2F Passenger to Freighter". Airbus. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ "A350F Facts and Figures" (PDF). Toulouse: Airbus. March 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ "Airbus Faces Dominant Boeing In Freighter Market". Aviation Week & Space Technology. 24 September 2019.

- ^ "Airbus and Bombardier Announce C Series Partnership". Airbus (Press release). 16 October 2017.

- ^ "Boeing and Embraer Confirm Discussions on Potential Combination". Boeing (Press release). 21 December 2017.

- ^ "Airbus introduces the A220-100 and A220-300". Airbus (Press release). 10 July 2018.

- ^ "Boeing and Embraer to Establish Strategic Aerospace Partnership to Accelerate Global Aerospace Growth". Boeing (Press release). 5 July 2018.

- ^ "Boeing Terminates Agreement to Establish Joint Ventures with Embraer" (Press release). Boeing. 25 April 2020.

- ^ a b Cochennec, Yonn (February 2003). "What goes up". Interavia Business & Technology. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012.

- ^ Kingsley-Jones, Max (22 January 2008). "Boeing-Airbus 2007 orders race closes with 'diplomatic' finish". Flight Global.

- ^ "Airbus A320 Family passes the 5,000th order mark" (Press release). Airbus. 25 January 2007.

- ^ "ANALYSIS: A320neo vs. 737 MAX: Airbus is Leading (Slightly) – Part I". Airways News. January 27, 2016. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ "Boeing positioned to narrow market share gap". Leeham Co. 22 September 2016.

- ^ Addison Schonland (10 July 2017). "The Big Duopoly Race". Airinsight.

- ^ Alex Derber (29 August 2018). "How The A320 Overtook The 737, And MRO Implications". Aviation Week Network.

- ^ a b c "Boeing's backlog market share vs Airbus falls below 40%". Leeham News. 14 July 2021.

- ^ "Orders & deliveries viewer". Airbus. Archived from the original on 30 December 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ "Boeing Orders & Deliveries". Boeing Press Calculations. Archived from the original on 2 October 1999. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Orders and Deliveries search page". Boeing. 31 December 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ Jens Flottau (9 February 2018). "Airbus And Boeing Consider Higher Narrowbody Production". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- ^ a b "Historical Orders and Deliveries 1974–2009" (Microsoft Excel). Airbus S.A.S. January 2010. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ "Airbus O&D". Airbus S.A.S. 31 December 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "Historical Deliveries". Boeing. December 2015. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ "Boeing: About Boeing Commercial Airplanes". Boeing. 31 December 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ David Kaminski Morrow (6 November 2017). "IAG lauds ownership-cost benefit of Level A330s". Flightglobal.

- ^ "Airbus and Boeing are head-to-head in the widebody sector". Flightglobal. 6 February 2018.

- ^ Adrian Schofield (17 May 2018). "Airbus, Boeing Size Asia-Pacific Carrier Opportunities". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- ^ "A350-900ULR: Singapore Airlines could be the sole customer". CAPA - Centre for Aviation. 11 August 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ "Boeing, partners expected to scrap Super-Jet study". Los Angeles Times. 10 July 1995. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ^ "Boeing 747-8 Family background". Boeing. 14 November 2005. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "SIA's Chew: A380 pleases, Virgin Atlantic disappoints". ATW Online. 13 December 2007. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- ^ Flottau, Jens (21 November 2012). "Emirates A350-1000 Order 'In Limbo'". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

Clark points out that 'the faster you fly [the A380], the more fuel-efficient she gets; when you fly at [Mach] 0.86 she is better than at 0.83.'

- ^ "Updating the A380: the prospect of a neo version and what's involved". Leeham News. 3 February 2014.

- ^ "A380 family presskit". 1 January 2012. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ Saporito, Bill (23 November 2009). "Can the A380 Bring the Party Back to the Skies?". Time. Archived from the original on 19 September 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ "The A380 global fleet spreads its wings as deliveries hit the 'century mark'" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Airbus, 14 March 2013.

- ^ "British Airways and Emirates will be first for new longer-range A380". FlightGlobal. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "Orders & Deliveries". Airbus. Archived from the original on 21 November 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ Quentin Wilber, Dell (8 November 2006). "Airbus bust, Boeing boost". The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ^ Robertson, David (3 October 2006). "Airbus will lose €4.8bn because of A380 delays". The Times.

- ^ Schwartz, Nelson D. (1 March 2007). "Big plane, big problems". CNN.

- ^ Clark, Nicola (12 July 2016). "Airbus to Sharply Cut Production of A380 Jumbo Jets". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Wall, Robert; Ostrower, Jon (12 July 2016). "Airbus Cuts A380 Production Plans". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ "747 model summary". Boeing. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ Jethro Mullen and Charles Riley (14 February 2019). "End of the superjumbo: Airbus is giving up on the A380". CNN. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Guy Norris (8 February 2019). "Current Orders To Maintain 747-8 Production Through Late 2022". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- ^ "747 Model Summary Through January 2020". Boeing. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Orders and deliveries". Airbus. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Air tanker deal provokes US row, BBC, 1 March 2008". BBC News. 1 March 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "The USAF's KC-X Aerial Tanker RFP: Canceled". Defense Industry Daily. 13 March 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Leeham News and Comment: How will Boeing profit from tanker contract? Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 12 July 2011, visited: 3 February 2012

- ^ Jim Wolf (11 July 2011), Boeing tanker strategy shifts $600 million to taxpayer, Reuters, archived from the original on 6 October 2011

- ^ "John McCain blasts Boeing overruns on Air Force tanker contract". Blog.al.com. 15 July 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ Defensenews.com: Boeing Lowers KC-46 Cost Estimate, 27 July 2011, visited: 3 February 2012

- ^ Gates, Dominic (1 March 2010). "Albaugh: Boeing's 'first preference' is to build planes in Puget Sound region". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "Airbus' China gamble". Flight International. 28 October 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ "Airbus officially opens U.S. Manufacturing Facility". Airbus. 14 September 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

Airbus inaugurated operations at its first ever U.S. Manufacturing Facility. The plant – which assembles the industry-leading family of A319s, A320s and A321s

- ^ "Qatar Airways A350 XWB factsheet". Airbus.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ Thomas, Geoffrey (4 April 2008). "Engines the thrust of the Boeing-Airbus battle". The Australian. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008.

- ^ Guy Norris (18 March 2013). "GE In, Rolls Out As Boeing Seeks 777X Approval". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- ^ Max Kingsley Jones (21 July 2014). "Rolls and Airbus – how the latecomer excelled". Flightglobal.

- ^ "Strong Euro Weighs on Airbus, Suppliers". The Wall Street Journal: B3. 30 October 2009.

- ^ "Statistical Summary of Commercial Jet Airplane Accidents - Worldwide Operations - 1959–2015" (PDF). Boeing. July 2016.

- ^ Robert Wall & Andrea Rothman (17 January 2013). "Airbus Says A350 Design Is 'Lower Risk' Than Troubled 787". Bloomberg. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

'I don't believe that anyone's going to switch from one airplane type to another because there's a maintenance issue,' Leahy said. 'Boeing will get this sorted out.'

- ^ Pfeiffer, Sylvia; Spero, Josh (18 March 2019). "Airbus cannot build fast enough to replace Boeing's 737 Max". Financial Times. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Aboulafia, Richard (18 March 2019). "Ugly As The 737 MAX Situation Is, Boeing Is Insulated By Airlines' Fear Of Missing Out". Forbes. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Tim Hepher (9 July 2012). "How plane giants descended into global 'price war'". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ Daniel Michaels (9 July 2012). "The Secret Price of a Jet Airliner". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Agustino Fontevecchia (21 May 2013). "Boeing Bleeding Cash As 787 Dreamliners Cost $200M But Sell For $116m, But Productivity Is Improving". Forbes.

- ^ a b c d Vincent Lamigeon (13 June 2013). "Le vrai prix des avions d'Airbus et de Boeing". Challenges.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Vinay Bhaskara (25 November 2014). "UPDATED ANALYSIS: Delta Order for A350; A330neo Hinged on Pricing, Availability". Airways News. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015.

- ^ DAVID KAMINSKI-MORROW (24 December 2014). "TransAsia to take four A330-800neo jets". Flight Global.

- ^ "Finnair has entered into a memorandum of understanding on the sale and leaseback of two A350 aircraft" (Press release). Finnair. 23 December 2015.

- ^ "In strategy shift, Boeing backs 7 MAX: sources". Leeham news and comment. 22 February 2016.

- ^ "Boeing Gives United A Smoking Deal On 737s To Block Bombardier From Gaining Traction". Forbes. 8 March 2016.

- ^ "ANALYSIS: Delta sees long upgauge runway ahead with A321s". FlightGlobal. 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Premier vol français (et vendéen) low-cost long courrier". Ouest France (in French). 13 September 2016.

- ^ "Aircraft Pricing - List vs. market". Airinsight. 16 May 2016.

- ^ Chris Bryant (13 November 2017). "Airbus Loses Its $1 Trillion Order Book". Bloomberg.

- ^ Tim Hepher (27 April 2018). "Airbus keeps plane pricing secrets just a little longer". Reuters.

- ^ Ernest S. Arvai (19 January 2018). "The Meaningless Game of List Prices". AirInsight.

- ^ "Boeing displaces Airbus at Hawaiian, wins 787-9 deal; airline cancels A330-800 order". Leeham. 20 February 2018.

- ^ Jon Hemmerdinger (10 July 2019). "Boeing faces pricing pressure as Airbus encroaches". Flightglobal.

- ^ "Too many orders? Yes, says consultant. No, says ex-super-salesman". Leeham News. 28 January 2019.

- ^ Robertson, David (4 October 2006). "Airbus will lose €4.8bn because of A380 delays". The Times. London.[dead link]

- ^ Associated, The (20 January 2011). "Southwest waiting to hear Boeing's plan for 737". BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on 24 January 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ "Orders and deliveries". Airbus. January 2024. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ "Commercial". Boeing. January 2024. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ "How Airbus went from zero to 10,000". Flight Global. 14 October 2016.

- ^ "Boeing: Orders and Deliveries". Boeing. 30 September 2024. Retrieved 10 October 2024.

- ^ "Airbus Orders and Deliveries" (XLS). Airbus. 30 September 2024. Retrieved 10 October 2024.

- ^ Oestergaard, Kasper (15 January 2024). "Airbus and Boeing Report December and Full Year 2023 Commercial Aircraft Orders and Deliveries". Flight Plan. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ "AIRBUS Results" (PDF). airbus.com. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ Materna, Robert; Mansfield, Robert E.; Walton, Robert O. (16 November 2015). Aerospace Industry Report, 4th ed. Lulu.com. ISBN 9780988183728. Retrieved 20 November 2022 – via book.google.co.uk.

- ^ Time Period Reports. boeing.com

- ^ "Western-built jet and turboprop airliners". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ "WESTERN-BUILT JET AND TURBOPROP AIRLINERS". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ "WESTERN-BUILT JET AND TURBOPROP AIRLINE". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ "WESTERN-BUILT JET AND TURBOPROP AIRLINE". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ "Airliner Census 2010 – fleet growth marginal and idle jets at record high". Flight Global. 23 August 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ [2][permanent dead link]

- ^ [3][permanent dead link]

- ^ [4][permanent dead link]

- ^ "ANALYSIS: The changing size and shape of the world airliner fleet". Flightglobal.com. 22 August 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ "World Airliner Census 2014" (PDF). D1fmezig7cekam.cloudfront.net. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ "World Airliner Census 2015" (PDF). D1fmezig7cekam.cloudfront.net. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ "12798". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ "ANALYSIS: FlightGlobal airliner census reveals fleet developments". Flightglobal.com. 8 August 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ "WorldCensus2017.pdf". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ "ANALYSIS: 787 stars in annual airliner census". Flightglobal.com. 14 August 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ "WorldAirlineCensus2018.PDF".

- ^ "World Airline Census" (PDF). Flight International. July 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2020.

- ^ "World Airliner Census 2020". Flight Global.

- ^ "Boeing Commercial Airplanes". www.boeing.com. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "Orders, Deliveries and Operators December 2023". Airbus. 15 January 2024.

- ^ "Don't Let Boeing Close The Door On Competition" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ O'Connell, Dominic; Porter, Andrew (29 May 2005). "Trade war threatened over £379m subsidy for Airbus". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 14 January 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ "Q&A: Boeing and Airbus". BBC News. 7 October 2004. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ "See you in court". The Economist. 23 March 2005.

- ^ "EADS Military Air Systems Website, retrieved September 3, 2009". eads.net. 13 May 2011. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "EU, US face off at WTO in aircraft spat". Defense Aerospace. 31 May 2005. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ "Flare-up in EU-US air trade row". BBC News. 31 May 2005. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ Milmo, Dan (14 August 2009). "US accuse Britain of stoking trade row with £340m Airbus loan". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "US refuses to disclose WTO ruling on Boeing-Airbus row". EU Business. 5 September 2009. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ "WTO says Europe subsidises Airbus, Boeing's rival, unfairly". USA Today. 3 March 2010. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "EU claims victory in WTO case versus Boeing". Reuters. Paris. 15 September 2010.

- ^ Freedman, Jennifer M. "WTO Says U.S. Gave at Least $5.3 Billion Illegal Aid to Boeing". Bloomberg. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "BBC News: WTO Airbus ruling leaves both sides claiming victory". bbc.co.uk. 19 April 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Lewis, Barbara (19 May 2011). "WTO gives mixed verdict on Airbus appeal". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 July 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "WTO final ruling: Decisive victory for Europe". LogisticsWeek. 25 March 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Khimm, Suzy (17 May 2011). "U.S. claims victory in Airbus-Boeing case". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "Airbus satisfy WTO obligations".

- ^ "European Communities — Measures Affecting Trade in Large Civil Aircraft".

- ^ "Sweeping Loss for Boeing in WTO Appeal". Airbus.com. 16 January 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ "United States — Measures Affecting Trade in Large Civil Aircraft — Second Complaint".

- ^ "WTO Boeing case: EU requests to impose countermeasures against the US". European Commission. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ "Next chapter in eight year old WTO conflict: Boeing's WTO Default Prompts $ 12 Bn in Annual Sanctions". Airbus. 27 September 2012. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ "WTO - dispute settlement - the disputes - DS487". Wto.org. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Reid Wilson (12 November 2013). "Washington just awarded the largest state tax subsidy in U.S. history". The Washington Post.

- ^ Jon Ostrower (10 December 2013). "Boeing Holds Bake-Off for Biggest Tax Breaks". WSJ.

- ^ "Exclusive: EU may challenge $8.7 billion U.S. tax breaks in Boeing-Airbus trade dispute - sources". Reuters UK. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020.

- ^ "Washington state's Boeing tax breaks are illegal, Europe charges". mcclatchydc.

- ^ Dominic Gates (10 February 2018). "Boeing's biggest trade fight could spark a U.S. confrontation with Europe". The Seattle Times.

- ^ "Next round in Airbus-Boeing WTO battle nears". Leeham. 14 February 2018.

- ^ "WTO issues ruling on EU appeal in Airbus-Boeing complaint". Leeham News. 15 May 2018.

- ^ Bryce Baschuk and Benjamin D Katz (28 May 2018). "U.S. Is Said to Open Door to Talks With EU on Airbus Settlement". Bloomberg.

- ^ Shane, Daniel; Kottasová, Ivana. "US threatens tariffs on $11 billion of European goods over Airbus subsidies". CNN. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ "In a broadside against Airbus, U.S. pursues aircraft tariffs". The Washington Post. Retrieved 9 April 2019.