Congress of Colombia

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 21 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 21 min

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of Colombia |

|---|

|

The Congress of the Republic of Colombia (Spanish: Congreso de la República de Colombia) is the name given to Colombia's bicameral national legislature.

The Congress of Colombia consists of the 108-seat Senate, and the 188-seat Chamber of Representatives, Members of both houses are elected by popular vote to serve four-year terms.

The composition, organization and powers of Congress and the legislative procedure are established by the fourth title of the Colombian Constitution. According to article 114 of the Constitution, the Congress amends the constitution, makes the law and exercises political control over the government and the public administration. In addition, the Constitution and the law grant other powers to Congress, including certain judicial powers and electing senior judges and other senior public officials.[1]

Both houses of Congress meet at the neoclassical Capitolio Nacional ("National Capitol") building in central Bogotá, the construction of which began in 1847 and was not concluded until 1926. Each house has its own election procedure and individual powers distinguishing them from the other, which are further discussed in the article for each individual house.

Congress

[edit]Eligibility

[edit]Each house has its own eligibility requirements established by the Constitution, but there are common rules of ineligibility and incompatibility (régimen de inhabilidades e incompatibilidades), determined by the Constitution.

Anyone who has been sentenced to deprivation of liberty (detention) at any time except for political crimes and culpable negligence; hold dual citizenship and are not native-born citizens; held a public employment position with political, civil, administrative or military authority or jurisdiction within the year prior the election; participated in business transactions with public entities or concluded contracts with them, or were legal representatives of entities which handled taxes or quasi-fiscal levies within the six months prior to the election; lost their mandate (investidura) as members of Congress or holds ties of marriage or kinship with civil servants holding civil or political authority may not be elected to Congress. In addition, relatives through marriage or kinship who are registered candidates for the same party for an office elected on the same day may not be members of Congress. The constitution also bans election to or membership in more than one office or body, even if the terms only overlap partially.[1] Members of Congress may not hold another public or private office (except university professorship); manage matters or conclude contracts, in their name or that of someone else, with public entities or persons administering taxes or serve as a member of any board or executive committee of decentralized public entities or institutions administering taxes.[1]

Violations of the rules of ineligibility, incompatibility, conflict of interest lead to the loss of one's mandate (investidura) as congressmen; as does an absence (during the same session) to six plenary sessions, failing to take their seat within eight days following the first meeting of the house, improper use of public funds or duly proven influence peddling. The Council of State rules on the loss of mandate within twenty days of the request made by a citizen or the executive committee of the appropriate house.

Members of Congress enjoy immunity for their opinions and the votes that they cast in the exercise of their office. For crimes committed during their term, only the Supreme Court of Justice may order the arrest and try them.[1]

Replacement of members

[edit]Members of Congress do not have alternates (suplente) and are only replaced in the event of a temporary or permanent absences, as decreed by law, by the next non-elected candidate on the list from which he/she was elected, ranked in order of registration or votes received. Permanent absences include death, physical incapacity, nullification of the election, justified and accepted resignation, disciplinary sanctions and the loss of one's mandate. Temporary absences include maternity leave and temporary deprivation of liberty from crimes other than those signalled in the paragraph below.

In the wake of the parapolitics scandal, a political reform in 2009 created the so-called silla vacía (empty seat) mechanism, according to which anyone who has been sentenced for membership, promotion or funding of illegal armed groups; drug trafficking; intentional wrongdoing against the public administration or mechanisms of democratic participation or crimes against humanity cannot be replaced. Likewise, any congressmen who resigns after having been formally indicted in Colombia for any of these crimes or who is temporarily absent after an arrest warrant has been issued for any of these crimes is not replaced. These rules not only apply to Congress, but to all other directly elected bodies - departmental assemblies, municipal councils and local administrative boards. These provisions were strengthened by the 2015 constitutional reform, which added fraudulent wrongdoings against public administration as a crime not resulting in replacement.[1]

Shared powers

[edit]Although each house of Congress serves a particular role and have individual powers distinguishing them from one another, both houses have certain powers in common, according to Article 135 of the Constitution; namely:[1]

- Electing its executive committees and its secretary general for a two-year period

- Request from the government the information that the house may need, except information regarding diplomatic instructions and classified documents

- Determine the convening of sessions reserved to address oral questions by congressmen to cabinet ministers and the answers of the latter

- To fill the positions established by law necessary for the execution of powers

- Seek from the government the cooperation of government agencies to improve the performance of their duties

- Organizing its internal maintenance of order.

- To summon (by writing, with five days anticipation) and require ministers, permanent secretaries and heads of administrative departments to attend sessions. In cases the officials fail to attend without an excuse deemed reasonable by the house, the house may file a censure motion.

- Propose censure motions against ministers, permanent secretaries and heads of administrative departments for matters related to their official duties or for ignoring the summons of Congress. A censure motion must be tabled by at least a tenth of the members of the respective house, and the vote takes place after the conclusion of a debate with a public hearing of the respective official. Approval of the motion requires an absolute majority, and, if successful, the official is removed from office. If unsuccessful, no new motion on the same matter may be proposed unless it is supported by new facts. The decision of a single house is binding on the other.

- Commissions of either house may also summon any natural or juridical person to testify (in writing or orally) during a special session on matters directly related to investigations pursued by the committee (Article 137).

Joint sessions

[edit]The Congress meets as a single body (Congreso pleno) only on exceptional occasions, determined by article 18 of Law 5 of 1992. These occasions are:[2]

- Inauguration of the President of the Republic, or the Vice President when acting as President

- Receive foreign heads of State and government

- Election of the Comptroller General

- Election of the Vice President in the case of a vacancy

- Recognizing the physical incapacity of the Vice President

- Electing magistrates of the Disciplinary Chamber of the Superior Council of the Judiciary

- Deciding on censure motions against cabinet ministers

In joint sessions of Congress, the President of the Senate acts as President of the Congress and convenes, chairs and directs the session.

Sessions

[edit]The Congress meets twice a year in two ordinary sessions: the first from 20 July to 16 December, and the second from 16 March to 20 June. These two sessions form a single legislative year, legally known as a legislature (legislatura), of which there are four during the course of a single congressional term.[citation needed]

The executive branch can call for extraordinary sessions at any time, but never after 20 June in an election year, and Congress may only discuss the issues submitted for its consideration by the government during these sessions.[citation needed]

Commissions

[edit]Each house elects permanent commissions, whose number, composition and responsibilities are determined by law. These commissions, whose existence stems from the Constitution, are known as permanent constitutional commissions and there are currently 14 in Congress - seven in each house. The current permanent commissions are:[3]

- First commission (19 senators, 35 representatives): responsible for constitutional amendments, statutory laws, constitutional rights and duties, territorial organization, regulation of control organisms, peace, structure organization of the central administration, ethnic affairs and other administrative matters.

- Second commission (13 senators, 19 representatives): responsible for foreign policy, defence, the military and police, treaties, diplomatic and consular appointments, foreign trade, borders, citizenship, immigration and aliens, military service, public honours and monuments, harbours and other foreign trade matters.

- Third commission (15 senators, 29 representatives): responsible for finance, taxes, monetary policy, central bank, authorization of loans, monopolies, economic regulation, national planning, financial markets, stock markets, insurance and savings.

- Fourth commission (15 senators, 27 representatives): responsible for budget laws, fiscal supervision, disposition of national goods, industrial property, patents, trademarks, management of national public institutions and offices, quality and price control for administrative contracts.

- Fifth commission (13 senators, 19 representatives): responsible for agriculture, the environment, natural resources, land management, fishing and maritime affairs, mining and energy.

- Sixth commission (13 senators, 18 representatives): responsible for communications, fees, public calamities, service delivery, communications media, scientific and technological research, radio and television, geostationary orbit, digital communication and computer systems, air space, public works and transport, tourism, education and culture.

- Seventh commission (14 senators, 19 representatives): responsible for civil servants, trade unions, mutual aid societies, social security, benefits, recreation, sports, health, community organizations, housing, economic solidarity, women and the family.

Legal commissions are those created by the law, responsible for specific matters outside the competence of the constitutional commission. Three legal commissions exist in both houses - human rights, ethics and congressional rules and document accreditation; two legal commissions exist only in the House of Representatives - public accounts and the investigation and accusation commission. In addition, there are special commissions and incidental commissions.[4]

Senate

[edit]The Senate has 102 elected members for four-year terms.

Electoral system

[edit]According to the Colombian Constitution, 100 senators (senadores) are elected from a single national constituency. The remaining two are elected in a special national constituency for Indigenous communities. The current threshold in order to obtain seats is 3% of valid votes nationally.

Eligibility

[edit]To be a senator, a person must be a natural-born Colombian citizen over the age of 30 at the time of the election. Representatives of indigenous communities seeking election as a representative of indigenous communities in the Senate must have held a traditional authority role in their community or have been the leader of an indigenous organization.

Exclusive powers of the Senate

[edit]- Approve or reject the resignations of the President and the Vice President.

- Approve or reject all military promotions conferred by the government on commissioned officers.

- Grant leaves of absence for the President in cases other than sickness, and determine the qualification of the Vice President to serve as President.

- Allow for the transit of foreign troops through Colombian territory.

- Authorize the Government to declare war on a foreign nation.

- Elect the Constitutional Court justices.

- Elect the Attorney General.[1]

- Take cognizance of the charges brought by the House of Representatives against the President (or whoever replaces him/her) and members of the Comisión de Aforados even if they may have ceased to exercise their functions. The Senate determines the validity of the charges concerning actions or omissions that occurred in the exercise of these duties, and adopts disciplinary measures if need be. The Senate's impeachment powers are limited, as the Constitution explicitly states the punishments which may be imposed, and, the accused faces trial before the Supreme Court of Justice for common crimes.

Chamber of Representatives

[edit]The House has 166 elected members for four-year terms.

Electoral system

[edit]The House of Representatives is elected in territorial constituencies, special constituencies and an international constituency.

Each department (and the capital district of Bogotá D.C.) form territorial electoral constituencies (circunscripciones territoriales). Each constituency has at least two members, and one more for every 365,000 inhabitants or fraction greater than 182,500 over and above the initial 365,000. For the current legislative term (2014-2018), 161 of the 166 House members are elected in territorial constituencies.

There are also three special constituencies, electing the remaining five members: one for Indigenous communities currently with one representative, one for Afro-Colombian communities (negritudes) currently with two representatives and one for Colombian citizens resident abroad currently with one representative. As a result of the 2015 constitutional reform, the number of seats allocated to Colombian citizens resident abroad will be reduced to one, from 2018 onward, as an additional special seat will be created for the territorial constituency of Archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina to represent the archipelago's Raizal community.[5]

The current threshold in order to obtain seats is 50% of the electoral quotient (total votes divided by total seats) in constituencies with over two seats and 30% of the electoral quotient in constituencies with two seats. Seats are then distributed using the distributing number, or cifra repartidora method explained in article 263 of the Constitution.

Eligibility

[edit]To be a representative, a person must be a Colombian citizen (by birth or naturalization) over the age of 25 at the time of the election.

Exclusive powers of the House

[edit]- Elect the Ombudsman.

- Examine and finalize the general budgetary and treasury account presented to it by the Comptroller General.

- Bring charges to the Senate, at the request of the investigation and accusation commission, for the impeachment of the President (or whoever replaces him/her) and members of the Comisión de Aforados.

- Take cognizance of complaints and grievances presented by the Attorney General or by individuals against the aforementioned officials and, if valid, to bring charges on that basis before the Senate.

- Request the aid of other authorities to pursue the investigations.

Legislative process

[edit]Congress's main power is to enact, interpret, amend and repeal laws (Article 150). Under this responsibility, some of its specific legal powers include approving the national development plan and related appropriations, defining the division of the territory, determining the structure of national administration (including creating, merging or abolishing ministries, departments and other national public institutions), authorizing the conclusion of contracts, loans and asset sales by the government; vesting the President with exceptional powers to issue decrees with force of law for a six-month period; establishing national revenues and expenditures; ratifying international treaties signed by the government and granting amnesties or commutations for political crime (with a two-thirds majority).

Types of laws

[edit]The Constitution differentiates between several different types of laws.

Organic laws (leyes orgánicas) regulate legislative activity, including the rules of Congress and both houses, the budgetary process and the approval of the national development plan. Their approval requires an absolute majority of the members of both houses (Article 151 of the Constitution).

Statutory laws (leyes estatutarias) regulate fundamental rights and duties and the procedures for their protection; the administration of justice; political parties and movements; electoral regulations; mechanisms for citizen participation (plebiscite, referendum etc.); states of exception; the military criminal justice system and electoral equality before major presidential candidates. Their approval, amendment and repeal require an absolute majority of the members of both houses and must be completed within a single legislative year. This procedure also includes prior revision by the Constitutional Court (Article 152).

Legislative acts (actos legislativos) amend the Constitution, and they may be presented by ten members of Congress although they may also be introduced by the government, 20% of municipal councillors and departmental deputies or a number of citizens equivalent to at least 5% of registered voters. The procedure for their approval is longer, as they must be approved in two consecutive ordinary sessions. Legislative acts are not the only method to amend the Constitution, nor does Congress hold exclusive powers of constitutional amendment.

Legislative initiative

[edit]Bills may originate in either house at the proposal of their respective members. However, legislative initiative is not limited to members of Congress. Bills may be proposed by the government through the appropriate minister(s); the Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court of Justice, the Council of Judicial Government, the Council of State, the National Electoral Council, the Inspector General, the Comptroller General and the Ombudsman may also propose bills on matters related to their duties. Finally, a number of citizens equivalent to at least 5% of registered voters at the time or 30% of municipal councillors or departmental deputies also hold legislative initiative under article 155, and these bills benefit from an accelerated procedure (see below).

The above notwithstanding, in certain cases bills may only be initiated by the government (see the second paragraph of article 154). Bills related to taxes may only be introduced in the House of Representatives and those involving international relations may only be introduced in the Senate.

All bills introduced must comply with certain requirements; among others, a title and number, articles and a statement of motives explaining the importance of the bill and the reasons for it.[6]

Legislative procedure

[edit]Upon the bill's introduction, the presidents of both houses decide to which permanent constitutional commission the bill will be sent. Once sent to a commission in each house, the chair of said commission will assign one or more member as speaker (ponente), who will study the bill and present a report (ponencia) on the bill's benefits (or lack thereof), potential improvements to be made or recommending that the bill be rejected. Upon publication of this report, the commission as a whole meets for debate and discussion on the contents of the report. The commission votes on the bill. A bill rejected during this first debate may be reconsidered by the respective house at the request of its author, a member of the house, the government or a spokesperson in case of a popular initiative.[6]

If the commission approves the bill, the commission's chair will again assign speakers, charged with reviewing the bill further and presenting a report for a second debate in the plenary of either house. The report is published for debate in the respective house, and the speaker explains to the full house the bill and the report. Similar to what happens during the first debate in commission, the floor is open to debate and testimony, followed by discussion of the bill in its entirety or by article. If the bill is approved by the house, it is sent to the other house, where it follows the same process through the equivalent commission and later to the floor of the house.[6]

Between the first and second debates, a period of no less than eight days must have elapsed, and between the approval of the bill in either house and the initiation of the debate in the other, at least 15 days must have elapsed (Article 159).[1]

A bill which has received a first debate but not completed the procedure in one legislative year will continue the process in the subsequent legislative year, but no bill can be considered by more than two legislatures.

In the case of differences between the versions approved by the two houses, a conciliation commission made up of an equal number of members of both houses is formed to re-conciliate both texts, or, if not possible, decide by majority vote on a text. The text chosen by the commission is sent to the floor of both houses for debate and approval. If differences persist, the bill is considered defeated (Article 161).[1]

Once a bill has been approved in two debates in each house, the bill is sent to the government (President) for its approval. The Colombian President formally lacks veto power, but may object to a bill and return it to the houses for second debates. The delay for returning a bill with objections is 6 days (no more than 20 articles in the bill), 10 days (21-50 articles) or 20 days (over 50 articles). If the prescribed delay expires without the government having returned the bill with its objections, the President shall approve and promulgate it. If the bill is again adopted by an absolute majority of the members of both houses, the President must sign the bill without objection. However, if the President objected to the bill for unconstitutionality, the bill will be sent, if the houses insist, to the Constitutional Court. The Court then has six days to rule on the bill's constitutionality; a favourable ruling forces the President to sign the bill, an unfavourable decision defeats the bill.[i]

The President may solicit the urgent or accelerated passage of a bill, by which the respective house must take a decision within a 30-day period (Article 163). In addition to this urgent procedure, it is also constitutionally established that priority is given to bills ratifying human rights treaties (Article 164).[1]

A number of citizens equivalent to 10% of registered voters may request a referendum for the repeal of a law. The law is repealed if an absolute majority of voters so decide, as long as turnout is over 25%. No referendums may be held on international treaties duly ratified, the budget or laws pertaining to fiscal and tax matters (Article 170).[1]

Images

[edit]-

IX Panamerican Conference

-

Laureano Gomez & Eduardo Santos in the Elliptical room of the National Capitol

-

Inauguration of Julio César Turbay

-

Mural by Santiago Martinez Delgado in the Colombian Congress.

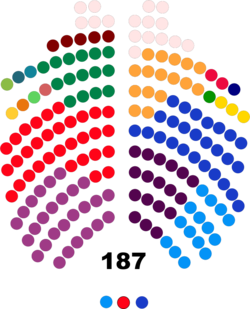

Latest election

[edit]Colombian parliamentary election, 2022

See also

[edit]- Chamber of Representatives of Colombia

- Senate of Colombia

- Politics of Colombia

- List of legislatures by country

Notes

[edit]- ^

- Alternative Democratic Pole (5)

- Humane Colombia (5)

- MAIS (4)

- Patriotic Union (4)

- Peace Force (1)

- ^ As part of a peace process agreement between the Colombian Government and the FARC rebels, FARC agreed to disarm in exchange for 5 parliamentary seats in the Senate

- ^ Indigenous seat

- ^ Indigenous seat

- ^

- Humane Colombia (13)

- Alternative Democratic Pole (10)

- MAIS (2)

- Fuerza de la Paz (1)

- Patriotic Union (1)

- ^ As a peace process agreement between the Colombian Government and the FARC rebels, FARC agrees to disarm in exchange for 5 parliamentary seats in the House of Representatives

- ^ Although it obtained a seat in the House of Representatives for the department of Magdalena, the party was dissolved in March 2024

- ^ Indigenous seat

- ^ Additionally, if the Court finds the bill partially unconstitutional, the bill is returned to the house where it originated. Once the responsible minister is heard, the bill is redrafted based on the Court's decision. Once completed, it is again transmitted to the Court for a definitive ruling.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Colombia 1991 (rev. 2013)". Constitute Project.

- ^ Ley la cual se expide el Reglamento del Congreso; el Senado y la Cámara de Representantes (Law 5) (in Spanish). 18 June 1992.

- ^ "Comisiones Constitucionales". Senado de la República. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ "Comisiones del Senado de la República". Senado de la República. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ "Constitución Política de 1991 (Artículo 176)". Secretaría General del Senado.

- ^ a b c "¿Cómo se tramita una ley?". Cámara de Representantes. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

External links

[edit]- (in Spanish) Senate of Colombia

- (in Spanish) Chamber of Representatives of Colombia

- (in Spanish) Congreso Visible, independent oversight of Congress by the Universidad de los Andes

KSF

KSF