Conservation and restoration of insect specimens

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

The conservation and restoration of insect specimens is the process of caring for and preserving insects as a part of a collection. Conservation concerns begin at collection and continue through preparation, storage, examination, documentation, research and treatment when restoration is needed.

Collection

[edit]

Insect collecting can be done in many different ways depending on the kind of insects being collected and from which habitats. Both hobbyists and professional entomologist have found particular ways to collect with minimal damage to their specimens. Following established techniques helps begin the conservation of insect specimens from the beginning by eliminating as much potential damage as possible. It must be done delicately to ensure that neither the collector nor the live insect itself will cause harm to the distinctive features such as wings, legs and antennae that give purpose to the collection. Special collection nets, traps and techniques must be utilized in consideration of how easily breakage can happen. A kill jar is often used to immediately immobilize the insect before it can damage itself.

Preparation

[edit]The way an insect specimen is prepared is often the first step in their conservation. They have to be carefully prepared with the appropriate methods depending on their size, anatomy, and potentially delicate features to ensure they will not break before they begin their role as a specimen available for study, research and display. Some specimens must be prepared using a dry method and others with liquid to preserve. The choice made will preserve key features necessary for identification and represent the insect's living form as closely as possible.

Pinning

[edit]

The process of pinning insect specimens is a dry method to preserve and display collections and requires special entomological equipment to accomplish effectively.[1] It is used primarily for hard-bodied, medium to large specimens and is beneficial for easier study and color preservation. Flies and butterflies, though they are partially soft-bodied, are also best preserved through pinning because when preserved in fluid their hairs and/or scales will either clot or fall off.[2] Some smaller specimens may still be pinned use minuten pins, which are much thinner, to avoid breakage. Insects are pinned on foam block or specialized pinning blocks that provide support for the limbs while drying and may be moved to another specialized, protected display case after they have dried completely, at which point they will be more brittle. The pin is most often driven through the thorax of the insect just to the right of the mid-line to preserve the appearance of at least one side should any damage occur from pinning. The exception is butterflies, dragonflies and damselflies, which are pinned through the middle of the thorax.[3] Enough of the pin must be left both above and below the specimen to allow for labeling below and handling.[3]

Carding

[edit]Carding is used when pinning would destroy too much of the specimen because its size is quite small.[4] A triangular point is cut from acid free card to ensure best conservation practice because it comes in direct contact with the specimen. A pin is then driven through the broad side of the point for mounting. A soluble glue that can be removed with solvents when necessary is used to adhere the right side of the thorax of the specimen to the point opposite the pinned side. The point is sometimes bent to allow the specimen to present in the same position as normally pinned specimens.

Wet specimen

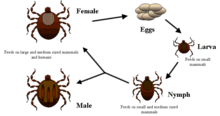

[edit]A wet specimen is a specimen preserved in fluid, often 70% alcohol. Specimens that would receive this preservation technique are usually soft-bodied, such as caterpillars, larva, and spiders because of their soft abdomens. This is done to minimize shriveling allowing the identifying characteristics to be preserved as true to life as possible. Hard-bodied insects may also be preserved temporarily in alcohol before pinning.[3]

Slides

[edit]Slides of very small insects are also kept as part of insect collections.

Core aspects of conservation

[edit]The American Institute for Conservation (AIC) describes in their Code of Ethics the aspects of conservation to include: preventive conservation, examination, documentation, treatment, research and education. Each of these areas also apply to the conservation and restoration of insect specimens.

Preventive conservation

[edit]Insect collections may suffer multiple types of degradation including fading colors from light exposure, mold growth from improper humidity and temperature levels, and infestations from pests that feed on dried insect,[5] but much of this is avoidable when proper preventive conservation practices are followed.

Routine cleaning

[edit]In addition to maintaining a clean storage environment for specimens, it is sometimes necessary to clean the specimens themselves. Cleaning incredibly delicate and brittle dry insect specimens is done carefully and methodically. The conservator chooses the appropriate method based on the kind of insect that needs cleaning and how robust it is. Cleaning tools vary widely, but generally clean watercolor brushes are used to gently dust the specimens, sometimes with a stereo microscope for very small specimens, warm water and/or alcohol baths used with or without an ultrasonic cleaner, and lens blowers to gently blow away dust, or dry the specimen after a cleansing bath.[6]

Proper storage

[edit]A common way to prevent damage from pests intent to feed on insect specimens and dust accumulation in a collection is to keep them in sealed boxes or cabinets.[7] When properly sealed, they can also aid in preventing damages cause by relative humidity (RH) and temperature fluctuations.[8] Wet specimens are kept in separate vials or jars and in a secure cabinet, tray or shelf. Fluid levels are regularly monitored to ensure specimens are completely immersed in fluid, though a well-sealed jar or vial will prevent excessive evaporation.[3]

Safe handling

[edit]Proper handling for insect specimens prevents the excessive breaking of legs, antennae and other body parts that could then easily be lost. Curved forceps may be used to allow more precision and less chance of the brittle specimen coming in contact with the handler. The handler picks up the specimen by the pin, which is placed with enough space below the specimen for the handler to put in the pinning block and enough space above to grip without touching the specimen.[3]

Integrated pest management

[edit]Integrated pest management (IPM) is a specialized modern pest control used in museums.[9] All IPM systems begin with regular sanitation and monitoring of collections to detect castings from various pests, and checking insect traps laid out to capture and identify which pests are present. Some pests, such as carpet beetles and flour beetles, feed on dried insects.[10] When an infestation is present, treatment may be necessary. Freezing is commonly used to rid insect collections of pests.[11] Alternatively, inert gases may be used for an anoxic fumigation – depriving the pests of oxygen to exterminate, and in extreme cases chemical fumigation proven to be safe for collections and people may be used.[12]

Examination

[edit]

Assessing the condition of an insect collection is done regularly and the results are recorded accordingly. The conservator observes the specimens in high detail remarking all areas of damage, or altered states of the specimen. Tools used during this process may include a strong light source, magnifying glass and handling tools that allow the conservator to pick up the specimen from the pin without touching it. The observations made during the examination process result in the conclusions drawn for a treatment plan if necessary.[13] The conservator is knowledgeable of the kinds of deterioration to look for specific to insect specimens.

Common agents of deterioration

[edit]- Pests – Evidence of pests are recognized in castings of insects, their droppings or the damages they have caused from chewing on specimens.

- Mold – Mold is most likely to grow when humidity is high.

- Verdigris – A blue-green hair-like crystallization caused by reaction to copper and brass entomological pins and the fats from the insects internal organs.[7]

Documentation

[edit]The documentation of insect specimens is carried out in many different aspects of a specimen's existence. Documented information begins with the capture of an insect. The collector records information about capture method, place and date of capture and any relevant habitat information in field notes. This information is then transferred to labels and collection records. The documentation path then continues with every recorded observation or treatment the specimen receives. Killing agents, preservation agents, rehydrating agents, and fumigants are all important to record.[14] This then informs any future decisions for conservation actions.

Labeling

[edit]As a minimum, labels contain the place and date of collection, and the identification of genus and species. On pinned insects, the labels are likewise pinned with the space left under the specimen on the same pin.[3] There are various ways to write the information on labels, but an ink that will not fade or come off in liquid is generally used. The paper is ideally 100% cotton or linen rag to avoid yellowing or embrittlement of the paper as it ages.[14]

Photographing and digitization

[edit]With improvements in digital photography and web resources, many natural history museums have begun a new kind of documentation through digitization, bringing high quality images and associated information to anyone with access to the Internet. Large databases can hold vast amounts of information improving research efforts.

Illustrating

[edit]Scientific illustration of insects is an older technique used to preserve information about collected insects. It visually documents insects, and unlike photography, can add intellectual ideas about anatomy and behavior of the insect through artists' renditions. Scientifically informed observation of specimens combined with technical and aesthetic skill yields the highly detailed illustrations necessary for the documentation of each species that is illustrated.[15]

Description of the state of the specimen and treatments

[edit]This area of insect specimen documentation comes after the close examination of specimens by conservators. The conservator records all of the visual information about the specimen that can be gleaned from detailed inspection. Conclusions are drawn from inspection and potential treatments are also documented to inform researchers and future conservators.

Research

[edit]Researching the collections of insects provides important information that develops knowledge about ecology, human health and crops.[4] Well-kept records aid the researcher in identifying whether there are differences in an observed specimen because of damages, treatments or deterioration. Research of the insect collections in museums can lead to new discoveries of species,[16] and provide an important historical resource.[17]

Treatment

[edit]Once a close observation reveals what issues are present in insect collections, the conservator makes a decision on actions to be taken. It is highly preferable that any treatment applied be reversible or done with little risk to the specimen. For example, broken limbs may be glued back on, which has traditionally been done with white glue. The advantage to white glue being that it is removable in warm water.[3] Another common problem is pest infestation. When dried insect collections have suffered an infestation, the affected specimens can be frozen or sealed with inert gases to kill the pests without harming the specimens.[12] Other treatments might include simply refilling wet specimens' jars with alcohol to ensure the specimens are completely submerged, cleaning specimens of dust and debris, or repositioning specimens for display or research. In the case that a specimen needs to be repositioned, the conservator will "relax" the specimen in a jar with a rehydrating substrate to move the limbs without breaking them. The technique used will vary among conservators. Some use a relaxing jar that the specimen is left in for days with the substrate of choice, others may choose to use a warm water bath with a drop of detergent. Whatever treatments are used are diligently documented.

Education

[edit]Conservation of insect specimens is done in large part to preserve the information for the public. The display of collections in museums and their interpretation offer one avenue that accomplishes this effort. However, websites offer a unique opportunity to disseminate information to a broad audience with layers of information to give general information or to provide depth where desired. These websites are often also provided by museums and their collections. Below is a list of some major educational endeavors with interests in insect specimens.

Large-scale insect specimen digital preservation efforts

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ DrWatson (2018-03-17). "Phasmid Preservation Techniques (part 1)". Neperos. Retrieved 2022-11-23.

- ^ Ross, H. H., 1962, How to collect and preserve insects p. 20 Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library 2017-03-16

- ^ a b c d e f g National Park Service, 2006, Curation of insect specimens Conserve O Gram 11/8 Retrieved 2017-03-30

- ^ a b Ross, H. H., 1962, How to collect and preserve insects p. 23 Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library 2017-03-16

- ^ Texas A&M Agrilife Extension, (n.d.) Bug hunter: Preservation considerations Retrieved 2017-04-06

- ^ Ingles-LeNobel, Johan, J. (March, 2017). How to clean insects Retrieved 2017-04-08

- ^ a b Icon, The Institute of Conservation, 2013, Care and conservation of zoological specimens Retrieved 2017-03-30

- ^ Szczepanowska, H., Shockley, F., Furth, D. G., Gentile, P., Bell, D., DePriest, P. T., Mecklenburg, M., Hawks, C. Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections. (2013). Effectiveness of entomological collection storage cabinets in maintaining stable relative humidity and temperature in a historic museum building. Collection Forum, 27(1-2), 43-53.

- ^ Buck, R. A., & Allman Gilmore, J. (2010). Museum registration methods 5th edition. Washington, DC: The AAM Press

- ^ Ross, H. H., 1962, How to collect and preserve insects p. 27 Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library 2017-03-16

- ^ Canadian Conservation Institute, (1997), Controlling insect pests with low temperature[permanent dead link] CCI Notes Retrieved 2017-04-08

- ^ a b Furth, D., December 1995, Pest control in entomological collections Insect collection news No. 10 Retrieved 2017-03-30

- ^ Appelbaum, B. (2010). Conservation treatment methodology. San Bernardino, California. ISBN 1453682112

- ^ a b Morse, J., December 1992, Insect collection conservation Insect collection news No. 8 Retrieved 2017-03-30

- ^ Hodges, E. R. S. (2003). The guild handbook of scientific illustration: Second edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- ^ Entomology Today, July, 2106, New assassin bug species discovered in museum collections and in the field Entomology Today Retrieved 2017-04-09

- ^ Entomological Society of America, Jan. 2016, ESA position statement on the importance of entomological collections Archived 2017-06-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2017-04-09

KSF

KSF