Conventicle Act (Sweden)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 3 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 3 min

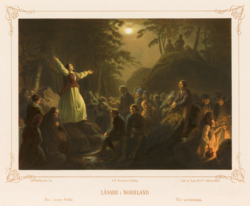

The Conventicle Act (Swedish: Konventikelplakatet) was a Swedish law, in effect between 21 January 1726 and 26 October 1858 in Sweden and until 1 July 1870 in Finland. The act outlawed all conventicles, or religious meetings of any kind, outside of the Lutheran Church of Sweden,[1] with the exception of family prayer or worship. The purpose was to prevent freedom of religion and protect religious unity, as such unity was regarded as important to maintain the control of the Crown over the public through the Church. The law only applied to Swedish citizens, while the religious freedom of foreigners was protected by the Tolerance Act.

History

[edit]The law was initiated in 1726 to prevent the popularity of Pietism, which was spreading rapidly in Sweden in the first half of the 18th century, and used against early proponents such as Thomas Leopold, Johan Stendahl, and Peter Spaak.[2]

During the 19th century, the Conventicle Act was used as a tool against the Shouter movement and the spread of free churches. Free church preachers, such as Baptist Fredrik Olaus Nilsson, were exiled. This law was one reason for emigration from Sweden to the USA in the 1840s and 1850s.[3]

During the 19th century, the law became controversial and was constantly debated in parliament. It was finally abolished in 1858. The new law stipulated that conventicles were not to take place in parallel with the services of the Lutheran Church without prior dispensation. This condition was abolished in 1868 and replaced with the condition that such gatherings were not to take place in the close surroundings of a Lutheran church.

The Conventicle Act was also in effect in Finland, until 1809 the Eastern part of Sweden. The Russian Grand Duchy of Finland kept her laws from the Swedish time until changed by the Diet, which abolished the Conventicle Act from 1 July 1870.

See also

[edit]- Kyrkogångsplikt – former legal obligation to attend weekly church services

- Conventicle Act (Denmark–Norway)

Notes

[edit]- ^ "1305-1306 (Nordisk familjebok / 1800-talsutgåvan. 8. Kaffrer - Kristdala)". runeberg.org (in Swedish). 1884. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- ^ "Jacob Benzelius".

- ^ Ljungmark, Lars (1996). Swedish exodus. Swedish Pioneer Historical Society. Carbondale: Published for Swedish Pioneer Historical Society by Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-1-4416-1933-4. OCLC 436089438.

References

[edit]- Frängsmyr, Tore (2004). Svensk idéhistoria: Bildning och vetenskap under tusen år, Part II 1809–2000. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur, p. 91f.

- "Konventikelplakatet" in Nordisk familjebok (first edition, 1884)

KSF

KSF