Coorparoo State School

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 30 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 30 min

| Coorparoo State School | |

|---|---|

Coorparoo State School, 2016 | |

| Location | 327 Old Cleveland Road, Coorparoo, City of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia |

| Coordinates | 27°29′42″S 153°03′38″E / 27.4949°S 153.0605°E |

| Design period | 1919–1930s (Interwar period) |

| Built | 1907, 1928–1933, 1942 |

| Architect | Department of Public Works (Queensland) |

| Official name | Coorparoo State School |

| Type | state heritage |

| Designated | 22 June 2017 |

| Reference no. | 650047 |

| Type | Education, Research, Scientific Facility: School – state (primary) |

| Theme | Educating Queenslanders: Providing primary schooling |

Coorparoo State School is a heritage-listed state school at 327 Old Cleveland Road, Coorparoo, City of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. It was designed by the Department of Public Works (Queensland) and built in 1907. It was added to the Queensland Heritage Register on 22 June 2017.[1]

History

[edit]Coorparoo State School (established 1876) is located in the Brisbane suburb of Coorparoo, approximately four kilometres southeast of the Brisbane CBD. It is important in demonstrating the evolution of state education and its associated architecture. It retains two urban brick school buildings (Block B: 1928–33; Block A: 1942) and a 10-post playshed (1907); set in landscaped grounds with retaining walls and fences (1920s–1940s), a sundial (1932–35), sporting facilities, and mature trees.[1]

Traditionally part of the land of the Jagera and Turrbul people, government auction of country allotments in the vicinity of the later Coorparoo State School began in 1856. A rural community developed and by 1875 residents proposed a primary school. Local landowner, Samuel Stevens, donated 2 acres (0.81 ha) of land fronting Old Cleveland Road for the school site, excised from Portion 177.[2][3][4] The name for the school, a variation of the Aboriginal name for the area, Cooraparoo, was proposed by the school committee.[5][6][1]

Coorparoo State School, comprising a low-set, two-room timber building with verandahs, and a school residence, opened on 31 January 1876, with 37 pupils enrolled. It cost £546 to erect, £95 of which was paid by the local community.[7][8][1]

The establishment of schools was considered an essential step in the development of new communities and integral to their success. Schools became a community focus, with the school community contributing to their maintenance and development; a symbol of progress; and a source of pride, with enduring connections formed with past pupils, parents, and teachers.[9][10][1]

The Coorparoo district continued to grow during the 1880s as Brisbane's population increased rapidly and moved to outlying areas, assisted by the development of public transport and the subdivision of land holdings. In 1887 a tramway was extended to Buranda, close to the western end of the Coorparoo district. In 1888 development had progressed so far that Coorparoo Shire, which included Stones Corner and parts of Holland Park and Camp Hill, was established. In 1889 the Cleveland railway line opened through the northern extent of Coorparoo Shire, adding to Coorparoo's popularity as a residential area. Coorparoo railway station was located about 700 metres (2,300 ft) northeast of the school. The concurrent increase in Coorparoo State School pupils led to the school building being extended in 1885, 1887 and 1889.[11][12][13][1]

However, development in Coorparoo Shire slowed after floods in 1889, 1890 and 1893 widely affected the district and the 1893 economic depression affected land sales. In 1900 there were fewer houses in Coorparoo than in 1890.[3][14][1]

Nevertheless, improvements continued at the school. The Queensland education system recognised the importance of play in the school curriculum and, as school sites were typically cleared of all vegetation, the provision of all-weather outdoor space was needed. Playsheds were designed as free-standing shelters, with fixed timber seating between posts and earth or decomposed granite floors that provided covered play space and doubled as teaching space when required These structures were timber-framed and generally open sided, although some were partially enclosed with timber boards or corrugated galvanised iron sheets.[15] The hipped (or less frequently, gabled) roofs were clad with timber shingles or corrugated iron. Playsheds were a typical addition to state schools across Queensland between c. 1880s and the 1950s, although less frequently constructed after c. 1909, with the introduction of highset school buildings with understorey play areas. Built to standard designs, playsheds ranged in size relative to student numbers.[16] There was a playshed on site at Coorparoo State School by 1887; located directly behind (southeast of) the school buildings. A new playshed, replacing the earlier one and in a similar position, was constructed by RS Exton for £176/8/0 in 1897. The final and only remaining playshed, with ten posts and a hipped roof, was constructed in late 1907 by James Price for £356.[17][18][19][20][21][1]

Suburban development in Coorparoo Shire accelerated after an electric tram extension opened in February 1915 from Stones Corner, along Old Cleveland Road, to Coorparoo State School.[22][23] Enrolments at the school continued to increase and an open-air annexe for infants was opened in October 1916 in the northeast corner of the site, following removal of the school residence.[24][25][26][1]

After World War I, Coorparoo experienced increased property sales and school enrolments. Between 1911 and 1921, Coorparoo Shire's population more than doubled from 2804 to 6635 residences.[27][28][29] School enrolments continued to rise, resulting in overcrowding; with two classes taught in the playsheds and two taught under the infants' open-air annexe. As a result, in 1924, the fifth and last extension to the timber school was built.[30][1]

An important component of Queensland state schools was their grounds. The early and continuing commitment to play-based education, particularly in primary school, resulted in the provision of outdoor play space and sporting facilities, such as ovals and tennis courts. Also, trees and gardens were planted to shade and beautify schools. In the 1870s, schools inspector William Alexander Boyd had been critical of tropical schools and amongst his recommendations stressed the importance of adding shade trees to playgrounds. Subsequently, Arbor Day celebrations began in Queensland in 1890. Aesthetically designed gardens were encouraged by regional inspectors, and educators believed gardening and Arbor Days instilled in young minds the value of hard work and activity, improved classroom discipline, developed aesthetic tastes, and inspired people to stay on the land.[31][1]

At Coorparoo State School, the small two-acre site provided only limited space for play and sporting facilities. To address this, more than 100 perches (2,500 m2) along Halstead Street were purchased in 1912. In 1925, the school acquired another 44.9 perches (1,140 m2) adjoining Tarlina Lane to the west of the school leading from Cavendish Road, while in 1926 the northeastern extent of the laneway was closed and adsorbed into the school grounds. In the same year, a further 32 perches (810 m2) of land adjacent to the Shire Hall on Cavendish Road, was purchased from the Brisbane City Council for play space. In the following year, the Department of Education purchased 12.6 perches (320 m2) of adjacent land. This, in addition to the previous Tarlina Lane purchase, became the site of the school pool, which opened on 3 August 1928, having cost £2000 to build.[32][33][34][35][36][1]

Meanwhile, lobbying of the Department of Public Instruction by the school committee from 1926 for a brick school building to accommodate the rising school population resulted in approval for a rebuilding scheme comprising two linked, two-storey brick buildings, to be constructed in stages.[37][1]

The urban brick school buildings constructed at Coorparoo State School were an individual design by the Department of Public Works. Brick school buildings were far less frequently built than timber ones, provided only in prosperous urban or suburban areas with stable or rapidly-increasing populations. All brick school buildings were individually designed with variations in style, size, and form, but generally retaining similar classroom sizes, layouts and window arrangements to timber schools to facilitate natural light and ventilation. However, compared to contemporary standard education buildings, these buildings had a grander character and greater landmark attributes.[38][39][1]

The first stage, constructed to the south-east of the existing timber classroom buildings, was completed and opened on 22 September 1928. The new two-storey wing (now called Block B) was 78 by 21 feet (23.8 m × 6.4 m) and accommodated 320 pupils. It comprised four classrooms on each floor with enclosed corridors. The classrooms on the first floor were divided by folding partitions to provide one large room (28 by 21 feet (8.5 m × 6.4 m)) for assembly purposes. The external brick walls above a string course were roughcast. Cavity walls were used which, combined with wide projecting eaves, provided temperature control inside the building. The construction was fireproof and soundproof between floors. It cost approximately £6009.[40][41][42][43][44][1]

Further additions to the school grounds were made in 1929 when an adjoining house and land to the west on Cavendish Road was purchased from Collin F Wolff for £1400. The school committee paid £400 of the cost in return for the proceeds from the sale of the house for removal. The Wolff family also donated £150 to the school in appreciation of the school committee's work in the interests of the present and future pupils of the school. The resultant playing area was called "Wolff Park" and opened by Reginald King, Deputy Premier and Minister for Works and Public Instruction, on 31 July 1929. At the same time, the Minister acknowledged the donation of a school bell by William Payard, a lifetime friend of the head teacher, Gustav Henry Hinrichsen.[45][46][34][47][48][49][1]

The Great Depression, commencing in 1929 and extending well into the 1930s, caused a dramatic reduction of building work in Queensland and brought private building work to a standstill. In response, the Queensland Government provided relief work for unemployed Queenslanders, and also embarked on an ambitious and important building programme to provide impetus to the economy.[1]

Even before the October 1929 stock market crash, the Queensland Government initiated an Unemployment Relief Scheme, through a work programme by the Department of Public Works. This included painting and repairs to school buildings.[50][51] By mid-1930 men were undertaking grounds improvement works to schools under the scheme.[52] Extensive funding was given for improvements to school grounds, including fencing and levelling ground for play areas, involving terracing and retaining walls. This work created many large school ovals, which prior to this period were mostly cleared of trees but not landscaped. These play areas became a standard inclusion within Queensland state schools and a characteristic element.[53] As part of the government's attempt to provide work for the unemployed, intermittent, relief work was carried out on the Coorparoo State School grounds. This work was inspected by the Minister for Public Instruction, Reginald King, in March 1932. Between 1932 and March 1935, the Committee employed a relief labourer on two occasions to keep the school grounds clean and tidy.[54][55][1]

With continuing growth in pupil numbers at Coorparoo State School, further accommodation was required. The second stage of the rebuilding scheme commenced when the tender opened for erection of an additional wing in July 1930.[56] This section, on the Old Cleveland Road side of the stage 1 brick building, was completed early in the 1931 and was opened by the Minister for Public Instruction, Reginald King. The two-storey addition comprised two classrooms, two cloakrooms and a teachers room per floor and accommodated 160 pupils. Its walls were of cavity brick, and cloakroom floors were concrete. The roof over the addition was finished with a fleche. Elevations were completed to harmonise with the existing building: brickwork above a cement bank course at first floor level was roughcast; and the face bricks below were finished with white struck joints. The extension cost £2337.[57][58][1]

After the Forgan Smith Labor Government came to power in June 1932 with a campaign that advocated increased government spending to counter the effects of the Depression, the government embarked on a large public works building programme. This was designed to promote the employment of local skilled workers, the purchase of local building materials and the production of commodious, low maintenance buildings which would be a long-term asset to the state. This building programme included: government offices, schools and colleges; university buildings; court houses and police stations; hospitals and asylums; and gaols.[59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66] Many of the programmes have had lasting beneficial effects for the citizens of Queensland, including the construction of masonry brick school buildings across the state.[1]

The programme enabled continuation of the rebuilding scheme for Coorparoo State School, warranted by the school's average attendance having grown to 1100 in 1932. A tender by Hector James Heaven of £1230 was accepted in May and the extension, to the eastern end of the stage 1 of Block B, was opened by Reginald King, MLA, on 29 October 1932.[67][68][69][70][71][1]

In 1933, the fourth and final section of Block B, with matching toilet blocks, was completed. This section, to the western end of the stage 1 building, comprised two classrooms on each floor with a verandah and a balcony and accommodated 160 pupils.[1]

The completed two-storey, symmetrical building contained 20 classrooms and accommodated 800 pupils and was set a few steps above ground level, with no undercroft. Both levels had a northwest verandah/corridor which accessed two stairs and eight southeast facing classrooms. A central bay of two classrooms, two cloak rooms and a store room projected north from the verandah making a total of 10 classrooms per level.[72] The total cost of the scheme was £11,513.[73][74][1]

Also, as part of the building programme, the whole of the available yard space was graded, and the main playing area south of Block B was bounded by concrete retaining walls. A chain wire fence surmounted the north and east walls and three broad flights of steps led down from the Parade Ground to the main playing area. At the top of each of these stairways was placed a tubular arch, designed by the Head Teacher, GH Hinrichsen.[74] A new tennis court and a new basketball court were completed in 1933. A retaining wall around the basketball court to its south and west was recorded on a 1936 site plan.[75] On 30 September 1933 Reginald King, MLA opened the fourth section of the brick school building, a second tennis court, two lavatory blocks, the concrete retaining walls around the playing field; and the tubular arches over stairways.[76][77][78][1]

Other improvements to the school grounds at this time included seven new palms, planted at the bottom of the Parade Ground on Arbor Day in May 1933, and many new flower beds and several hibiscus hedges, laid out by the Head Teacher with donated plants.[74][1]

With the completion of Block B, the school committee's attention focused again on increasing the grounds of the growing school. In 1934, 51 perches (1,300 m2) facing Old Cleveland Road adjoining the western boundary of the school were purchased from MW Thompson for £1206, of which 1/3 (£400) was paid by the school committee. Removal of the house followed. The property's fence and retaining wall on the Old Cleveland Road boundary and the mature shade trees were retained, while the land was partially graded for use as an infants' playground. In the following year, the committee also purchased a 17-perch (430 m2) allotment adjacent to the new playground for £75 for inclusion in the infants' playground. The playground was later named Hinrichsen Park after the head teacher.[79][34][80][81][82][1]

Other improvements to the school grounds between 1932 and 1935 funded by the school committee, included erection of a pergola, garden seats and a pedestal and sun-dial in Wolff Park. The school committee was also responsible for installing electric light in the school between 1932 and 1935.[83][55] In 1938, a rockery and watering system were installed. A fence with a pergola and steps leading down to the infants' area were erected, and lawns and flower beds were established and 40 roses planted.[84][1]

In June 1940, the Minister for Public Instruction advised that funding was available to build the final stage of the school's rebuilding scheme. Drawings for the building, in keeping with the earlier proposed design, were completed by DPW architect, Gilbert Robert Beveridge, that month.[1]

The new brick building (now called Block A), located in front of Block B, formed the fifth and final section of the brick school. It comprised two floors with an undercroft play area, similar to other urban brick schools and Depression-era brick school buildings. Some buildings of the original school was demolished to enable its completion.[85] In January 1941 commencement of Block A's construction, at a cost of £17,252, was announced by the Minister for Public Instruction and Public Works (Harry Bruce).[86][87] Work on the building was well advanced by December 1941.[88] Teaching commenced in Block A on 24 August 1942.[89][90][1]

The urban brick school building provided accommodation for 370 pupils in nine classrooms: four on the first floor and five on the second. The head teacher's room was on the ground floor with staff rooms and cloakrooms on each floor. The four classrooms on the ground floor were separated by folding partitions. The upper level classrooms were divided by solid masonry walls with central connecting double doors. Twin stairs led from the ground to the first floor central bay. Through a small portico and short hall (flanked by a teachers room and cloak room), a verandah corridor gave access to the southeast facing classrooms. Stairwells connecting the three levels were positioned at both ends of the building. The upper level replaced the portico, one teachers room, and the short hall of the lower level with a classroom. Block A was connected to the Block B centrally at ground and first floor levels by covered ways. Corridors, verandahs, balconies and cloak rooms had concrete floors; the remaining floors were of wood and the ceilings of fibro-cement. It replaced three timber classroom buildings located in front of Block B, two of which were to be moved to Wolff Park and used as domestic science and vocational classrooms.[91][92][93][87][1]

Sometime after completion of Block A, the surrounding grounds were excavated and graded and new retaining walls and fences provided.[94] A new block plan, dated 1940, showed removal of the existing concrete retaining wall and fencing in front of Block A (Old Cleveland Road frontage), replaced by a new wall, and a chain wire fence, and excavation of the grounds to new levels. The retaining wall from the Thompson property was retained. The existing concrete retaining wall and fencing along School Lane were removed, and a new concrete wall and chain wire fencing, extending to the existing gates, were erected. Trellis fencing was erected above the retaining walls to the east and west of Block A.[95][96][1]

Prior to the completion of Block A, war in the Pacific region commenced in December 1941, resulting in the Queensland Government closing all coastal state schools in January 1942 due to fear of a Japanese invasion. Although most schools reopened on 2 March 1942, student attendance was optional until the war ended. The closed schools were sometimes occupied for defence purposes, and some schools remained closed "for special reasons" after the rest had reopened.[97][98][99] Typically, schools were a focus for civilian duty during wartime. At many schools, students and staff members grew produce and flowers for donation to local hospitals and organised fundraising and the donation of useful items to Australian soldiers on active service.[100] Slit trenches, for protecting the students from Japanese air raids, were also dug at Queensland state schools, often by parents and staff.[1]

Coorparoo State School contributed to the war effort in a number of ways. The Chief Air Warden held Air Raid Precautions meetings once a month. Brisbane Commercial High School students, whose school in the city closed, came to Coorparoo for lessons in the buildings in Wolff Park. About 1941 Coorparoo State School was officially approved as a combined Decontamination and First Aid post. Initially the first aid post was set up in one of the old buildings, but after the completion of Block A, its basement was used as an Air Raid Post, set up with beds and medical supplies. An air raid siren was mounted on an electric light pole outside the school on Old Cleveland Road. Air raid practice was carried out at the school. Slit trenches were dug around the small playground facing Old Cleveland Road and sand bag trenches made along the Wolff Park fence. Ordinary needlework was replaced by knitting scarves and socks which were distributed to relatives of pupils on active service abroad. Five rugs were given to refugees. From February 1942, Australian soldiers recuperating at the Australian Army hospital at nearby Loreto Convent were given permission to use the school grounds and swimming pool.[101][1]

After World War II, the Department of Public Instruction was largely unprepared for the enormous demand for state education that began in the late 1940s and continued well into the 1960s. This was a nationwide occurrence resulting from immigration and the unprecedented population growth now termed the "baby boom". Queensland schools were overcrowded and, to cope, many new buildings were constructed and existing buildings were extended.[102] This was the case at Coorparoo State School.[1]

After removal of the relocated timber school buildings, a high-set timber building of three classrooms (now called Block C) was completed in 1950.[103] During the 1950s a number of additions were undertaken leading up to the school's peak enrolment of 1600 in 1958.[104][105] A timber infants school building was erected in Wolff Park in 1956.[106] A completely new infants school building, on a separate site to the east of the school was undertaken in 1959–60.[107] The building was occupied by pupils and staff from 29 August 1960.[108][1]

Additional playing space was also needed. Circa 1945, the Methodist Church, the owner of the Queen Alexandra Home, located to the east of the school, granted permission for the school to use some of its grounds for sport and other activities at certain times.[109] Negotiations by the Department of Public Instruction with the Methodist Church to purchase the home, land and buildings of the Alexandra Home were finalised in October 1958.[110] A new cricket pitch was created on this land to the east of the school's playing grounds.[111][112][113] In 1968 a school reserve R1394 (Lot 501 see Sl8907) was created, comprising the school site and the former Nicklin house (Queen Alexandra Home - Lot 501) and totalling 11 acres (4.5 ha) 2 roods (22,000 sq ft; 2,000 m2) 9 perches (230 m2).[114][115][1]

Plans for proposed grounds improvements were drawn in July 1946. These included concrete paving, sewerage, and topdressing of the grounds, but their implementation was not completed until 1953, at a cost of £760 with the school paying half. The school was connected to the city's sewerage system in 1953–1954 at a cost of approximately £3075. The plan shows two timber buildings removed from the site of future Block C in 1950. At this time, the sun dial was located to the northeast of the future Block C.[116][111][117] In 1968 two new tennis courts and two new basketball courts were built.[118][1]

Changes to the urban brick school buildings were made from the 1970s. In 1972 the verandahs were enclosed. In the following year, all four ground floor classrooms of Block A were combined and converted into a library.[119][1]

At the beginning of semester 2 of 1987 the infants school and primary school re-joined on the original Coorparoo State School site.[120][1]

Major renovations to the school were undertaken from 1999. Dividing walls between classrooms in Block A were removed at this time. Three additional classrooms were created by extending and upgrading existing buildings in 2001. Between 2001 and 2003, the 1928 swimming pool was demolished for construction of a new music building on its site. A new swimming pool was located to the east of the former playing field on land excised from the Alexandra Home property. In 2003, a three-storey teaching block was constructed on the playing field site. A multipurpose hall was constructed front Old Cleveland Road in 2009; its construction coinciding with the demolition of the 1932 toilet block southwest of Block A.[121][122][123][124][1]

Reconfiguration of the school grounds has taken place over the years, resulting in the current 3.252-hectare (8.04-acre) site in 2017.[125][126][127][128][1]

Throughout the school's history, social events to fund-raise and celebrate milestones have taken place. In 1933 a commemorative re-union dance to celebrate the school was held in the first school building prior to its demolition.[85] In 1936 diamond jubilee celebrations were held. The school's 100th anniversary was celebrated on 10 April 1976. Part of the commemorations was the release of a video of a day at Coorparoo in 1943.[129] Another re-union of past pupils in 1994 attracted over 600 former students from around Australia.[130][1]

In 2017, the school continues to operate from its original site. It retains its urban brick school buildings and 10-post playshed, set in landscaped grounds with sundial, retaining walls, fences, stairs and balustrading, sporting facilities, playing areas, and mature shade trees. Coorparoo State School is important to the Coorparoo district as a key social focus for the community, as generations of students have been taught there and many social events held in the school's grounds and buildings since its establishment.[1]

Description

[edit]

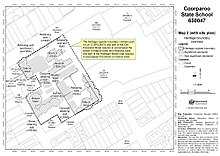

Coorparoo State School occupies part of a large, 3.252-hectare (8.04-acre) site fronting northwest onto Old Cleveland Road, a main thoroughfare through the suburb of Coorparoo, four kilometres southeast of Brisbane CBD. Attractive views are had to and from the school and it is conspicuous in the area as it occupies the crest of a modest ridge, has long frontages to principal thoroughfares, stands directly beside the retail and civic centre of the area, and includes striking architecture, open playing fields, and impressive mature trees.[1]

Two remarkable urban brick school buildings stand symmetrically and axially aligned with and facing the school's front entrance on Old Cleveland Road - Block A (1942) in front of Block B (1928-33), connected by a two level enclosed walkway (1942). Despite being built nine to 14 years apart, Block A, Block B, and the walkway are a cohesive design with matching form, style, and material use. A playshed (1907) stands nearby and the grounds include retaining walls and terraced play grounds, and mature trees.[1]

Block A (1942)

[edit]

Block A is a symmetrical two-storey building set high on an enclosed undercroft level and has a tall hipped roof clad with corrugated metal sheets. At the roof's central peak is a prominent metal ventilation fleche with round cupola. The building's facades are defined horizontally with three materials: smooth-rendered masonry with lined coursing at undercroft level; facebrick for the ground floor up to the sill level of the first floor; and painted pebble dash stucco above. The building character is softened through the use of attractive, simple, and low maintenance materials with minimal decorative features, including a restrained use of dark glazed bricks contrasting with the unglazed main body of the building and smooth-rendered concrete dressings, flat window hoods with scrolled brackets, and keystones. A triangular pediment at the parapet highlights the building's central entrance and features the school name.[1]

The building uses are separated by its levels with an undercroft level of open play space below two levels of teaching rooms. The form of each level is also clearly defined by its use, comprising a central block of primarily teachers' rooms and former cloak rooms projecting in front of a long wing of classrooms that have a stairwell at either end. Connecting the two parts is a verandah providing circulation along the front (northwest side) of the long wing. The verandah has arched openings on the ground floor and square openings with a glazed brick balustrade on the first floor, however, both levels of verandah have been enclosed with later louvres and sheet material, which is not of cultural heritage significance. At either end of the verandah on the ground floor are secondary entrances reached via stairs from the front garden. These are highlighted by a porch with a semi-circular smooth rendered concrete hood. The front entrance and porches have an arched fanlight above timber French doors with panelling and bolection moulding. Mounted on the wall either side of the front door are marble tablets dedicated to two chairmen of the early school committee.[1]

The building layout is highly intact in its original configuration; although new lightweight partitions have been inserted in a number of places. The formerly open undercroft has been partitioned to create a tuckshop, toilets, and a storeroom but retains open areas with original perimeter timber seats and rounded corners to the brick pillars. The ground floor configuration is highly intact. It retains its front staff rooms either side of a short foyer entrance, however, the cloak rooms have been enclosed by a partition to create store or staff rooms. The wall between verandah/corridor and the classrooms retains large double-hung windows, fanlights, and timber French doors, however, the folding partitions that formerly divided all classrooms on this level have been removed to form a long space (used as a library in 2017). This space includes some later glazed partitions and a raised platform that are not of cultural heritage significance. The first floor is a similar layout to the ground and is also highly intact, however, two masonry partitions have been removed to make four classrooms into two. The classrooms on both levels retain their ceilings lined with sheets and battens, with those of the first floor having lattice ventilation panels. The stairwells at either end are intact, retaining iron balustrades and turned, clear-finished timber handrails and bare concrete stairs.[1]

Old Cleveland Rd boundary walls and fences from W.jpgIn front of Block A is a modest garden, terraced via a cement rendered boundary retaining wall with pillars and metal palisade. A concrete path leads from the street through the garden on axis between flanking Poinciana trees (Delonix regia) in flat lawns before dividing to either side to reach a branching stair up to the front door. The broad concrete stairs have simple iron balustrades. Framing the northeast and southwest sides of Block A are concrete retaining walls and broad stairs up to the higher land behind. Projecting from the centre of the rear of Block A is a two-storey covered walkway to Block B. The walkway is a facebrick structure with a hipped roof clad with corrugated metal sheets. It has open arches on the ground floor and is enclosed on its first floor with timber-framed casement windows with fanlights, which are an early or possibly original feature.[1]

Block B (1928–33)

[edit]

Block B stands on higher land behind (to the southeast of) Block A and matches it in materials, style, detail, height, and floor levels by omitting an undercroft. The building has a tall hipped roof clad with corrugated metal sheets, topped by a metal ventilation fleche, matching Block A. Its form and layout is similar to Block A with a front block of classrooms and cloak rooms projecting in front of a long wing of classrooms with a stairwell toward either end. As in Block A, Block B has secondary entrances into the ground floor via concrete stairs with iron balustrades up to porches with round concrete hoods. The verandah on both levels is enclosed with later windows and sheet material, which is not of cultural heritage significance.[1]

In 2017 the building operates as administration and staff rooms for the school and four former classrooms have had lightweight partitions installed to create offices. Some doorways have been made in brick partition walls to connect rooms. The timber folding partitions of the ground floor end classrooms have been removed; otherwise the layout remains intact.[1]

The first floor contains classrooms and has had minor alterations to create larger classrooms. It retains two of three sets of timber folding partitions between classrooms, however, these have been moved and installed nearby into later partitions - the original four classrooms have been converted into three. Openings have been made in brick partitions and one cloak room has been incorporated into a classroom by removing the brick partition completely and closing it off from the corridor.[1]

Despite these changes, the building is highly intact. It retains original fabric including timber French doors with fanlights and iron hardware, high-set casement windows in the wall between verandah and the classrooms, brass window hardware, timber batten and sheet ceilings with lattice ventilation panels on the first floor, and the stairwells retain bare concrete floors and steps with iron balustrade and turned timber handrails.[1]

Blocks A and B

[edit]The interiors of Block A and B and the corridor link between them are simple and functional yet have a generous character with lofty ceilings and high level of natural light and large windows. Both blocks face north-northwest; correspondingly, the long wing of classrooms behind them face south-southeast, to which direction they have large areas of tall timber-framed casement windows with matching fanlights (although some windows on the southern side of Block B have been replaced with similar designs) allowing high levels of natural southern light into the classrooms. [1]

Playshed (1907)

[edit]

Standing behind (south) of Block B is a timber framed playshed. It has ten timber posts and a timber framed hipped roof clad with corrugated metal sheets. It stands on a concrete slab and has timber perimeter seats, which are later replacements. The posts bear notches that indicate former perimeter enclosure.[1]

Grounds

[edit]The grounds of the school are terraced to form large flat platforms. Behind (to the southeast of) Block B, these were originally parade grounds and playing areas but have had shelter sheds and other teaching buildings constructed on them, which are not of cultural heritage significance, although one open area remains. The terraces are formed via concrete retaining walls (c. 1928-1942) that show they were formed and poured in situ. The ground generally falls away behind Block B and stairs are incorporated to reach lower terraces. A small section of Brisbane tuff retaining wall forms a small terrace near Cavendish Road.[1]

On the Old Cleveland Road boundary stands a retaining wall from the former Thompson Estate. It is a masonry wall rendered with roughcast stucco and has piers with moulded caps. Between the piers is a balustrade of two metal pipes and at the centre of the wall are steps up to the former gate, which has been blocked off.[1]

The school grounds contain mature trees, including: rows of camphor laurels (Cinnamomum camphora) and figs (likely weeping fig, Ficus benjamina). The trees stand to the southwestern side of the former Thompson Estate, at the boundary to and Cavendish Road and in a row away from the road, and lining the retaining wall of the playing field near Halstead Street. At some locations, these are in lines marking the former boundaries of the school grounds.[1]

A sundial stands in the grounds in one of the large formerly-open playing terraces to the southwest of Block B (near the northeast corner of Block C). It has a sandstone base and the flat top holds a brass plate of the sundial although the gnomon has been removed. The side of the mount has a brass plaque reading "Wolff Park". [1]

Other buildings and structures are not of cultural heritage significance.[1]

Views of the Brisbane CBD and surrounding neighbourhood occur from Block A and B and the school grounds. With its open setting contrasting with the suburban residential and retail streetscapes, with its large grassed oval and framed by mature trees, Coorparoo State School is an attractive and prominent element in the built landscape.[1]

Heritage listing

[edit]Coorparoo State School was listed on the Queensland Heritage Register on 22 June 2017 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the evolution or pattern of Queensland's history.

Coorparoo State School (established in 1876) is important in demonstrating the evolution of state education and its associated architecture in Queensland. It retains excellent, representative examples of government designs that were architectural responses to prevailing government educational philosophies, set in landscaped grounds with sporting facilities, landscaping features, and mature trees.[1]

Two urban brick school buildings (1928–33, 1942) represent the culmination of years of experimentation with natural light, classroom size and elevation by the Department of Public Works (DPW), and also demonstrate the growing preference in the early 20th century for constructing brick school buildings at metropolitan schools in developing suburbs. Additions undertaken during the 1930s are the result of the Queensland Government's building and relief work programmes, which stimulated the economy and provided work for men unemployed as a result of the Great Depression.[1]

The suburban site with playshed (1907), mature trees, sundial (1932–35), sporting facilities and other landscaping features demonstrates educational policies that promoted the importance of play and a beautiful environment in the education of children.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a particular class of cultural places.

Coorparoo State School is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a Queensland state school with later modifications. These include: teaching buildings constructed to individual designs; and generous, landscaped sites, with mature trees, assembly and play areas, and sporting facilities.[1]

The urban brick school buildings are intact, excellent examples of individually designed buildings of their type. They demonstrate the principal characteristics through their highset form; linear layout, with classrooms and teachers rooms accessed by verandahs; undercrofts used as open play spaces and for additional rooms; loadbearing, masonry construction, with face brick piers to undercroft spaces; and roof fleches. They demonstrate use of the stylistic features of their era, which determined their roof form, joinery and decorative treatment. Typically, urban brick school buildings are configured to create central courtyards, and are located in suburban areas that were growing at the time of their construction.[1]

The Playshed is an intact, excellent example of a standard 10-post, hipped-roof playshed, designed to provide all weather play space for children.[1]

The place is important because of its aesthetic significance.

The urban brick school buildings at Coorparoo State School have aesthetic significance due to their beautiful attributes: identifiable by their symmetrical layout; consistent form; scale; materials; elegant composition; finely crafted timber work; and decorative treatment.[1]

These buildings remain intact and demonstrate a continuation of site planning ideals initiated by the placing of the original urban brick school building in a prominent position at the top of the sloping site. The beauty of the school's setting is enhanced by mature trees and formal landscaping elements such as retaining walls, stairs, gardens and a sundial with pedestal.[1]

Sited on high ground on Old Cleveland Road, the school has views to the Brisbane CBD and its urban brick school buildings are also significant for their contribution to the Old Cleveland Road streetscape.[1]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

Schools have always played an important part in Queensland communities. They typically retain significant and enduring connections with former pupils, parents, and teachers; provide a venue for social interaction and volunteer work; and are a source of pride, symbolising local progress and aspirations.[1]

Coorparoo State School has a strong and ongoing association with the surrounding community. It developed through the fundraising efforts of the local community and generations of children have been taught there. The place is important for its contribution to the educational development of its suburban district and is a prominent community focal point and gathering place for social and commemorative events with widespread community support.[1]

Notable students

[edit]- Pauline Hanson, politician

- Dorothy Hill, geologist

- Campbell Royston Scott, architect

- Lachlan Chisholm Wilson

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu "Coorparoo State School (entry 650047)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ Department of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Heritage Database and Register. <https://culturalheritage.datsip.qld.gov.au/achris/public/public-registry/home>, accessed 29 March 2017

- ^ a b Judith Rechner, The Old Coorparoo Shire: A Heritage Drive Tour, BHG, Brisbane, 1991, p. 2

- ^ DNRM, CoT10327248, 27Jul1878.

- ^ Peg Bolam, Coorparoo State School 1876-2001 125th anniversary: a Coorparoo chronicle. Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo, Qld, 2001, p. 6

- ^ Michael A Endicott, Coorparoo Stones Corner Retrospective, Augustinian Historical Commission, Manly Vale, NSW, 1979, p. 9.

- ^ "Opening and closing dates of Queensland Schools". Queensland Government. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 1876-2001 125th anniversary, pp. 6-7.

- ^ Project Services, "Mount Morgan State High School" in Queensland Schools Heritage Study Part II Report, for Education Queensland, 2008, pp.4-5

- ^ Paul Burmester, Margaret Pullar and Michael Kennedy Queensland Schools A Heritage Conservation Study, a report for the Department of Education, 1996, pp.87-8.

- ^ Leslie E Slaughter, Coorparoo Stones Corner Centenary 1856-1956, publisher, Brisbane, 1956, p. 71, 2017

- ^ Project Services, "Coorparoo SS", p. 10

- ^ Google maps, 2017: McKellar's Official Map of Brisbane & Suburbs (reflecting 1880s subdivisions), Queensland Gvt Printer, Brisbane, 1895, sheet 9.

- ^ Project Services, "Coorparoo SS", p. 4.

- ^ Burmester et al, Queensland Schools: A Heritage Conservation Study, p.16v.

- ^ Burmester et al, Queensland Schools: A Heritage Conservation Study, pp.21, 97. Type B/T5

- ^ QSA Item ID14289, Series 12607 School Files (Correspondence) for State School, Site Plan 17 Mar 1887 attached to Memorandum from Supt of School Buildings to Under Secretary, Dept Public Instruction, 14 Mar 1887

- ^ 'Official Notification', The Queenslander, 16 Jan 1897, p. 150

- ^ 'Public Works Department', The Brisbane Courier, 9 Nov 1907, p. 14

- ^ Department of Public Works. Report of the Department of Public Works for the Year ending 30 June 1908, p. 11

- ^ 'Coorparoo School', The Brisbane Courier, 11 Feb 1911, p. 14.

- ^ 'Set-back and Recovery', Brisbane Courier, 16 Aug 1930, p. 23

- ^ Leslie E Slaughter, Coorparoo Stones Corner Centenary 1856-1956, publisher, Brisbane, 1956, p. 71.

- ^ 'Coorparoo State School', Telegraph, 16 Oct 1915, p. 10

- ^ ePlan drawing No 15697693, "Coorparoo State School Rebuilding Scheme (2nd Stage)", 25 March 1930

- ^ Endicott, Coorparoo Stones Corner Retrospective, p. 39.

- ^ Project Services, "Coorparoo SS", p. 4

- ^ University of Queensland. "Queensland Places: Coorparoo and Coorparoo Shire", <http://queenslandplaces.com.au/coorparoo-and-coorparoo-shire> accessed 22 Feb 2017

- ^ 'Booming City', Daily Standard, 2 Nov 1922, p. 4.

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, p. 22.

- ^ Burmester et al, Queensland Schools: A Heritage Conservation Study, pp.4, 48-9.

- ^ QSA Item ID14289 Coorparoo No 219 State School correspondence, letter from Crown Solicitor to the Under Secretary, Dept Public Instruction, 7 Nov 1912

- ^ QGG, 10 May 1926, p. ? in QSA Item ID14290, Series 12607 School Files (correspondence) for State Schools

- ^ a b c Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo SS Centenary, Souvenir History 1876-1976, Coorparoo SS, Brisbane, 1976, p. 13

- ^ DNRM, CoT 10910017

- ^ Peg Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, pp. 22-3.

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, p .23.

- ^ Burmester et al, Queensland Schools: A Heritage Conservation Study, pp.18, 99

- ^ QSA, Item ID 13693, Deputy Govt Architect, "Preliminary Estimate of Modified Plan - New State School Ascot", 9 May 1919.

- ^ 'Coorparoo School New Brick Building', Brisbane Courier, 24 Sep 1928, p. 11

- ^ Department of Public Works. Report of the Department of Public Works for the Year Ended 30 June 1928. Queensland Govt Printer, Brisbane, 1928, p. 7

- ^ 'Dept of Public Works', The Telegraph, 4 Oct 1928, p. 6

- ^ Department of Public Works. Report of the Department of Public Works for the Year Ended 30 June 1929. Queensland Govt Printer, Brisbane, 1929, p. 5

- ^ 'Coorparoo State School', The Brisbane Courier', 12 Mar 1929, p. 7.

- ^ 'Generous Help', The Brisbane Courier, 1 Aug 1929, p. 3

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, p. 25

- ^ 'New Playground', Telegraph, 1 Aug 1929, p. 12

- ^ 'New Playground', The Telegraph, 1 Aug 1929, p. 12

- ^ 'Gift to Coorparoo State School', The Telegraph, 2 Aug 1929, p. 7.

- ^ 'Relief of unemployment: big programme contemplated', The Telegraph, 24 July 1929, p.5

- ^ 'Unemployment: the relief scheme', The Telegraph, 26 July 1929, p.5.

- ^ DPW, "Report of the Department of Public Works for the year ended 30 Jun 1930", p.15.

- ^ Burmester et al, Queensland Schools: A Heritage Conservation Study, p.58.

- ^ 'Work of Relief Men', The Telegraph, 17 Mar 1932, p. 9

- ^ a b 'The School Committee Report' by E J Wruck cited by Coorparoo State School. Coorparoo State School magazine. Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo, Qld, 1937, p. 11.

- ^ 'Metropolitan Schools' The Telegraph, 14 Jul 1930, p. 2.

- ^ DPW, Report for Year Ending 30 June 1931, pp. 5, 36

- ^ Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo SS Centenary, Souvenir History 1876-1976, Coorparoo SS, Brisbane, 1976, p. 11. "Coorparoo School", The Telegraph, 1 Apr 1931, p. 12.

- ^ 'Labor at the Helm', The Worker, 20 Jul 1932, p.8

- ^ 'Queensland Parliament', The Northern Miner, 17 Aug 1932, p.2

- ^ 'Public Buildings', Daily Mercury, 19 Oct 1933, p.7

- ^ DPW, Report of the DPW for the Year Ended 30 June 1934, Queensland Government Printer, Brisbane, 1934, pp.6-8

- ^ DPW, Report of the DPW for the Year Ended 30 June 1935, Queensland Government Printer, Brisbane, 1935, p.2

- ^ Report of the DPW for the Year Ended 30 June 1936, Queensland Government Printer, Brisbane, 1936, p.2

- ^ 'State will spend over £460,000: big building plans', The Courier-Mail, 28 Dec 1933, p.9

- ^ Report of the DPW for the Year Ended 30 June 1939, Queensland Government Printer, Brisbane, 1939, p.2.

- ^ 'Coorparoo State School', The Brisbane Courier, 10 Jun 1932 p. 9

- ^ Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo SS Centenary, Souvenir History 1876-1976, Coorparoo SS, Brisbane, 1976, p. 11

- ^ Coorparoo State School. Coorparoo State School Magazine. Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo, Qld, 1931, p. 8

- ^ 'School Extension', The Telegraph', 31 Oct 1932, p. 2

- ^ 'Coorparoo State School', The Telegraph, 23 Nov 1932, p. 6.

- ^ Project Services, "Coorparoo SS", p. 8.

- ^ DPW, Report of the Dept of Public Works for the year ended 30 June 1933, Qld Government Printer, Brisbane, 1933, p. 9

- ^ a b c Coorparoo State School. Coorparoo State School magazine. Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo, Qld, 1933, p. 9.

- ^ Coorparoo State School. Coorparoo State School magazine. Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo, Qld, 1933, p. 9. The retaining wall is depicted on the 1936 Brisbane City Council Water Supply and Sewerage Detail Plan No. 672 (BCC Archives, Brisbane).

- ^ 'Important Step', Courier-Mail, 2 Oct 1933, p. 5

- ^ 'Additional Wing for Suburban School', The Courier-Mail, 28 Sep 1933, p. 14

- ^ Coorparoo State School. Coorparoo State School magazine. Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo, Qld, 1933, p. 8.

- ^ Property transferred on 29 August 1934 - see DNRM, CoT: 10850205, 10696145

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, pp. 32, 33

- ^ ePlan Drawing No 15697759, Coorparoo SS additions of New Building, 1940

- ^ Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo SS Centenary, Souvenir History 1876-1976, Coorparoo SS, Brisbane, 1976, p. 13.

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, p. 33

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, p. 42.

- ^ a b 'A Severed Link', The Brisbane Courier, 28 Jul 1933, p. 8.

- ^ 'Coorparoo School Improvement to Cost 17,252', The Telegraph, 30 Jan 1941, p. 5.

- ^ a b 'Coorparoo's New School', The Courier-Mail, 31 Jan 1941, p. 10.

- ^ E J Wruck, "The School Committee Report" cited by Coorparoo State School. Coorparoo State School magazine. Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo, Qld, 1941, p. 5.

- ^ 'Kangaroo Point and East Brisbane Schools to Open', The Telegraph, 12 Aug 1942, p. 4

- ^ DPW, Report of the DPW for the Year Ended 30 June 1942, Queensland Government Printer, Brisbane, 1942, p. 4.

- ^ E J Wruck, "The School Committee Report" cited by Coorparoo State School. Coorparoo State School magazine. Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo, Qld, 1941, p. 5

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, p. 49

- ^ 'Coorparoo School Improvement to Cost 17,252', The Telegraph, 30 Jan 1941, p. 5

- ^ Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo SS Centenary, Souvenir History 1876-1976, Coorparoo SS, Brisbane, 1976, p. 12.

- ^ ePlan Drawing No 15697770, Coorparoo SS Additions- New Building Block Plan, Sep 1940

- ^ ePlan Drawing No 15697649, Coorparoo State School additions New Block Plan. Drawing by GR Beveridge, March 1941.

- ^ Ronald Wood, Civil Defence In Queensland During World War II, 1993, p.79

- ^ 'Schools reopen

- ^ some await shelter survey', The Courier Mail, 2 March 1942, p. 3.

- ^ Burmester et al, Queensland Schools A Heritage Conservation Study, a report for the Department of Education, 1996, pp.60-62.

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, pp. 46, 49, 52.

- ^ Project Services, Queensland Schools Heritage Study Part II Report, for Education Queensland, January 2008, pp.28-31.

- ^ Project Services, "Coorparoo SS", p. 10.

- ^ 'Coorparoo SS', Your Brisbane Past and Present, <http://www.yourbrisbanepastandpresent.com/2011_11_01_archive.html>, 4 Nov 2011 accessed 22Feb17

- ^ DPW. Report of the Dept of Public Works for the year ended 30 June 1956. Qld Government Printer, Brisbane, 1956, p. 17.

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, p. 58.

- ^ DPW. Report of the Dept of Public Works for the year ended 30 June 1960. Qld Government Printer, Brisbane, 1960, p. 14. Repeated in DPW Report for the Year Ending 30 June 1961.

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, p. 61.] In 1956 Block C was extended by three classrooms to the < >. [ePlan, Drawing No 15697627, Coorparoo SS additions, Oct 1956.

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, p. 56.

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, p. 59.

- ^ a b Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo SS Centenary, Souvenir History 1876-1976, Coorparoo SS, Brisbane, 1976, p. 14

- ^ DNRM, JFP6-96_1961

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, pp. 64, 65.

- ^ QGG, 1968, Vol 3, p 1239

- ^ DNRM Survey Plan Sl.4903.

- ^ ePlan, Drawing No 11793210, Coorparoo State School Proposed Concrete Paving Sewerage & Paving & Topdressing grounds, 23 Aug 1946

- ^ DPW, Report of the Dept of Public Works for the year ended 30 June 1954. Qld Government Printer, Brisbane, 1954, p. 14.

- ^ Coorparoo State School, Coorparoo SS Centenary, Souvenir History 1876-1976, Coorparoo SS, Brisbane, 1976, p. 14.

- ^ Project Services, "Coorparoo SS", p. 11.

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, p. 82.

- ^ DNRM,QAP618-163, 2006 aerial

- ^ Project Services, "Coorparoo SS", p. 11

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, pp. 103, 104

- ^ ePlan Drawing No 22596024, Building the Education Revolution Program: Coorparoo SS, 13 Sep 2009.

- ^ DNRM, Survey Plan, SL806603

- ^ DNRM, SL811022

- ^ DNRM, SL 839014

- ^ DNRM, SP228474.

- ^ Alan Denby (1943) and Neil Sternquist (1976), "28124 Coorparoo State School Video 1943, ca1980", John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

- ^ Bolam, Coorparoo State School 125th Anniversary, p. 90.

Attribution

[edit]![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Coorparoo State School, an entry in the Queensland Heritage Register published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 4.0 AU licence, accessed on 25 January 2018.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Coorparoo State School, an entry in the Queensland Heritage Register published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 4.0 AU licence, accessed on 25 January 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Coorparoo State Schoo (1976). Coorparoo State School centenary : souvenir history 1876-1976. Baskerville. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Coorparoo State School : 125 years of memories. Coorparoo State School. 2001. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Bolam, Pet (2001). Coorparoo State School 1876-2001 125th anniversary : a Coorparoo chronicle. The Author?. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

KSF

KSF