County courthouse architecture in colonial America

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 16 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 16 min

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

Court justice was administered during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in the territories that would become the United States subsequent to the American Revolution in buildings that comprised colonial, county, and municipal structures. The most common local and regional territorial unit for the administration of justice within the English colonies was the county. These structures were designed with varying degrees of size and sophistication based on local needs and budgets and were typically inspired by European precedents which comprised different arrangements of adjudicative, clerical, deliberative, and enforcement oriented spaces and rooms, and featured different architectural motifs and symbolic and functional accoutrements.[1]

European precedents

[edit]English shire and hundred courthouses and moot halls

[edit]

Early Modern England during the time of North American colonization during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was divided into shires, the basic first level administrative division, and hundreds, the basic second level administrative division. The shires and hundreds could be further subdivided into third and fourth level political divisions such as ridings, tithings, hides, wapentakes, and parishes. While the term shire roughly translates as county, and forms the root word of the title of sheriff, which in the American colonies was a county official, an English shire roughly corresponded in population to an American colony compared with an American county, and the shire court compared more similarly in form and function to an American colonial general court than to an American county court. Each English shire could perhaps be divided into a dozen or more hundreds, which were composed of a hundred hides, generally agreed to be the amount of land required to feed one middle-class family. The English hundreds of the American colonial period were roughly proportional in population and powers to a colonial American county.[2]

Each English shire and hundred during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries would have contained a moot hall, or meeting hall, where local executive, legislative, and juridical business would have been transacted. These meetings would have typically taken place four times a year in the upper shire moot hall and would have been known as the general court, the quarterly court, the assizes, or the court of general sessions of the peace. These meetings would have been where serious crimes, such as felonies punishable by death, would have been tried, as well as lawsuits for higher amounts of damages, probation of large estates, and other matters of concern to the shire. The lower moot halls in the hundreds would have typically met monthly and been referred to as the monthly court, the magistrates' court, the lower court, or the county court, and would have jurisdiction over disputes of lower significance, such as misdemeanor criminal trials, lawsuits over smaller amounts of debt, licensure of local businesses, and care for widows and orphans. The moot halls in the shires and hundreds were also referred to as courthouses, as they housed the local court, the root word being borrowed from the French couer, meaning heart, as these local meetings were considered to be at the heart of local administrative business. [3]

Each hundred court would be composed of a panel of eight to fifteen or more magistrates, who were upper class local businesspeople and farmers, with no formal training in the law, who volunteered their time to hear cases once a month. Each hundred would retain a court clerk, who was a licensed attorney who had a great deal of influence over the hundred court, offering opinions on legal matters and deciding which causes were heard by the court in what order, in addition to recording the details of cases such as writs of attainder, judgements of debt, business licenses, and probations of estates. Each of the magistrates would rotate the duty of bailiff amongst themselves for a year or two each, which was a paid position enforcing court orders, collecting judgements of debt, ensuring order was maintained in the court, and carrying out punishments.

Each shire court in England was presided over by a sheriff. In addition to the sheriff's enforcement functions overseeing the work of the bailiffs in the hundreds of the shire, the sheriff was the shire's chief executive, similar to a governor or mayor, collected all of the shire's taxes, of which he was allowed to keep a percentage, represented the monarch in matters of state, and could even serve as the judge of certain court cases. A panel of councilors would serve the legislative and juridical functions in the shire court similar to the role of the magistrates in the hundred courts. The secretary, or custus rotolundum, or keeper of the scrolls, would fill the role of the clerk of the shire court. Finally, constables and jailers would call cases before the shire court and carry out court orders such as whippings and brandings.[4]

Dutch four-scissors and stadt and municipal courts and meeting halls

[edit]

In the areas of the American colonies first settled by the Dutch, including New York and New Jersey, seventeenth and eighteenth century courthouse architecture was inspired by Dutch precedents. The basic Dutch deliberative and juridical structure was known as a four-scissors, and the main room of the courthouse consisted of a square of four benches facing inwards known as a schepenbank, on which the provincial or city shepenen would sit, facing the litigants. The schepenen were similar to a panel of English magistrates, with a shute acting as the enforcement officer of the court, similar to a county sheriff. The shute would have broad powers to perform mild to moderate tortures on criminal defendants, accept and reject confessions and witness statements, offer opinions to the schepenen on a suspect's guilt or innocence, and carry out punishments. Once the schepenen reached their verdict on a criminal case it was customary for the shute to break a straw in front of the convict, symbolizing that no appeal from the court was possible. Similar to a county court clerk, a pensionary would be paid by the schepenen to act as the law officer of the Dutch court, and would also act as the chief executive of the province or stadt with jurisdiction over everything outside the scope of practice of the shute, such as receiving taxes from cities and conducting relations with other Dutch provinces.[5]

French and Spanish cabildos and palaces of justice

[edit]In the areas of colonial North America that were first settled by other European states such as France and Spain, including Florida and Louisiana, local courthouses often combined many of the features of English moot halls and courthouses with elements of traditional Roman architecture, often combining deliberative spaces for magistrates and judges with an executive palace for the local mayor or governor, as well as rooms for other social functions. However, these local courthouse buildings had less influence on extant English and American examples because of their remoteness and lack of sophistication through most of the American colonial period, except to the south of the original 13 colonies where elaborate examples still exist.

Use of space

[edit]Courtrooms and meeting rooms

[edit]

The typical American colonial county courthouse would typically evolve from basic log or frame structures to more sophisticated brick or stone structures as counties grew in population and developed a larger base for tax revenue. Often the first purpose built public structure erected in a county was the county jail, while the magistrates held court in rented homes or taverns until a permanent courthouse could be built.[1]

The first generation of purpose built county courthouses in the seventeenth and early eighteenth century were relatively unornamented log and frame structures, typically one room with a courtroom of perhaps 25 by 40 feet, and perhaps a side building for the clerk's office. If no clerk's office was provided, the clerk would store court records at home and only bring them to court once a month during court sessions. A separate building for storing court records was desirable due to the risk of fire in the main structure, in the event of record storage in the courthouse the county business would be destroyed.

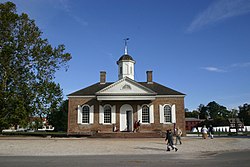

As counties raised the budgets for more permanent courthouses, a brick T-shaped structure became popular in Virginia and other mid-Atlantic colonies. The courtroom was housed in the central arm of the T with the clerk's offices and magistrates and jurors' deliberation rooms adjoining the courtroom on the shorter arms of the T. The facade of the T-shaped courthouse often consisted of an outdoor arcade with multiple arches where bystanders could smoke tobacco and discuss news and activities within the county. The doors from the arcade typically led directly inside the main courtroom, with no interior passageways. There could be multiple exterior doors into the courtroom and perhaps additional front doors to the side leading into the clerk's offices.[6]

The interior of the courtroom contained a balustrade, known as the bar of the king's justice, which separated the public area of the courtroom from the deliberative area for the court officers, including attorneys, magistrates, clerks, and sheriffs. The area in front of the balustrade was known as the bystanders' gallery as it contained no seating for the public. Instead, litigants, witnesses, and audiences would stand by, waiting for their cases to be called. On either side of the bystanders' gallery would have been doors leading to the clerk's offices and magistrates and juror's deliberation rooms in the shorter arms of the T-shaped structure.

At the ends of the balustrade where it met the side walls of the courtroom would have been enforcement boxes for the sheriff and jailer. These boxes would consist of elevated platforms raised the same height as the magistrates' bench. The height of the platforms symbolized that whether a magistrate was serving on the panel or as a sheriff or jailer, their social status in the court was considered equal. In the center of the balustrade would have been benches for the attorneys. These benches were fitted at floor height to symbolize that the social standing of the attorneys was literally and figuratively lower than that of the magistrates who sat several feet above them, although higher than that of the bystanders who had to remain standing for the duration of the court proceeding. These benches were typically fitted with a small shelf to hold legal documents during court. In between the attorneys' benches and the magistrates' platform was a large table for the clerk of the court, typically covered with a green tablecloth, large enough to hold maps and record different court proceedings.

The rear elevation of the courtroom structure that contained the magistrates' bench platform could be apsodial, curvilinear, or rectilinear. Apsodial courtrooms, which were based on ancient Roman courthouse architecture, had a curved wall at the back of the courtroom which formed a semicircle around which the magistrates' benches were affixed. Rectilinear courtrooms had flat, rectangle shaped walls, although the magistrates' bench could still be curved, forming negative space behind it in the corners. The magistrates' bench was typically about three feet off the floor level, with steps at either end to facilitate access. A railing typically held a shelf for court documents and separated the elevated platform for the magistrates from a bench at floor level immediately in front of it for the jurors. This symbolized that the jurors were equal in social status to the attorneys and lower in standing and importance than the county magistrates. However, the position of the jury at the front of the courtroom rather than to the side symbolized the central role that juries could play in judging court cases.[7]

Deliberative spaces for magistrates and jurors

[edit]To the sides of the main courtroom in one of these county courthouses would have contained the deliberation rooms for the magistrates and jurors. The magistrates' deliberation room would have been more ornamented with upholstered chairs, table, bookcases, woodworking, wainscotting, and finishing. As the main courtroom would have likely been too large to effectively heat with a fireplace or stove, the clerk's office would present too much fire risk from a fireplace, and the jury room was legally prohibited from containing a fireplace, the magistrates' room often contained the only fireplace in the colonial county courthouse. The jury room would have been much plainer, as English common law stipulated that juries were to be sequestered "without light, meat, drink, or heat" in order that they might be encouraged to reach a quicker verdict to avoid wasting the time of the unpaid magistrates. It likely would have only contained a wooden table, chairs, and a chamber pot.

Clerical offices and record storage

[edit]The clerk's office would likely have been to one of the shorter sides of the T in the T-shaped colonial county courthouse. It would have contained a desk for the clerk to prepare the court docket, typically covered with a green tablecloth, and court record storage in the form of trunks, boxes, or shelves. This would have allowed the court clerk to keep the county records in good form and able to be moved if necessary, for example in the case of a fire or a change in the county seat.

Jails

[edit]Colonial American county jails were typically smaller than their English and European counterparts and often corresponded more closely to an English village lockup than even an English regional bridewell let alone a county prison, with inmates being transported to the colonial jail by the county sheriff for longer stays on more serious charges and felonies. The smaller colonial American counties might have had a jail composed of one or two cells on a single floor. Inmates slept on the floor seated on straw mattresses and went to the bathroom on gravity fed toilets which drained into exterior cess pits which were drained by hand with a bucket and shovel. The larger colonial county jails might have had a capacity of twenty or thirty inmates divided between a half dozen cells organized around a central yard. Separate accommodations might have been provided for debtor's prisoners, with perhaps a few added features such as fireplaces. Some county jails might have adjoined a house for the sheriff or jailer, which may have shared some facilities with the jail such as kitchens, storerooms, gardens, and perhaps the sheriff's or jailer's offices.[8]

Architectural features

[edit]Brickwork

[edit]

The most common form of brickwork on colonial American public buildings during the mid to late eighteenth century was Flemish bond, in which each layer of bricks consisted of two stretchers laid parallel to each other and the wall, alternated with one header, laid perpendicular to the wall and the other bricks. This would have created a strong and attractive pattern of bricks on the double thick wall. Alternative styles of bricklaying would have included common bond and English bond. These bricks would have been supplemented at the foundation with additional rows of bricks for structural support and drainage of runoff water.[9]

Exterior ornamentation

[edit]The Georgian style, named after King George of England, was a popular architectural style for public buildings in colonial America. Sir Christopher Wren was a popular English architect of the period and is believed to have designed a few buildings in colonial America in the Georgian and English Baroque styles. Columns were used sparingly compared to styles such as Federal, Classical Revival, and Greek Revival, and were typically small, perhaps only framing an entrance rather than the entire facade. The facade could contain a cornice with dentils or keystones but were less elaborate than later styles such as egg and dart patterns. Buildings were often topped with a cupola, or small decorative dome, which helped ventilate hot air out of the upper stories of the building during the summer months. Statues, such as lady justice blindfolded holding the sword and scales, didn't emerge until the end of the colonial period into the nineteenth century.[10]

Interior ornamentation

[edit]Interior ornamentation on colonial American public buildings, such as wood paneling and wainscotting was relatively modest compared with private buildings and English examples of the time due to the colonial emphasis on fiscal conservatism, and courthouses, sheriff's houses, governor's mansions, and colonial capitols were often pejoratively referred to as palaces if the construction costs exceeded the undertaker's bid or the fittings were considered too elaborate. Wainscoted wooden panels typically only extended up the walls to chair rail height, or behind elevated platforms, to the level of the windows. Fireplaces didn't typically contain mantels, but the paneling would have extended higher up the wall than it would have in the remainder of the room in order to avoid soot buildup. Wall surfaces without wooden paneling would have been whitewashed with plaster almost annually.

Accoutrements and iconography

[edit]Crests and seals

[edit]The English coat of arms was frequently displayed outside colonial American county courthouses and above the presiding magistrate's bench in the courtroom. These were typically replaced with state seals after the colonies became independent subsequent to the American Revolution.[6]

Law enforcement tools

[edit]

Colonial American courthouse sheriff's boxes would have contained a large staff which served multiple purposes. It could be banged against the floor of the sheriff's box to call the court to order, used to prevent the public in the bystander's gallery from crossing the bar of the king's justice if they weren't a court officer in order to assault or intimidate attorneys, magistrates, or jurors, or used to lean against when standing for long periods of time. Colonies in the north often had colored tipstaffs, or wooden staffs with colored tips, in their courthouses which were used to announce the verdict of a case if the bystander's gallery was too small to admit all of the spectators into the courthouse during a high-profile case. A green tipstaff would be displayed to the public if the defendant was found not guilty and a red tipstaff would be displayed if the defendant was found guilty.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Surrency, Erwin C. (1967). "The Courts in the American Colonies". The American Journal of Legal History. 11 (3): 253–276. doi:10.2307/844011. ISSN 0002-9319. JSTOR 844011.

- ^ Brookes, Stuart (2020). "Domesday Shires and Hundreds of England". Archaeology Data Service. doi:10.5284/1058999.

- ^ Brodie, Allan; Brodie, Mary (8 September 2016). Law Courts and Courtrooms 1: The Buildings of the Criminal Law. Historic England. ISBN 978-1-84802-393-2.

- ^ Burr, Martin (2007). "The Anglo-Saxon Judiciary". British Legal History Conference (PDF). Oxford.

- ^ Van De Meerendonk, Suzanne; Van Eikema Hommes, Margriet; Vink, Ester; Van Drunen, Ad (2017). "Striving for unity: The significance and original context of political allegories by Theodoor van Thulden for 's-Hertogenbosch Town Hall". Early Modern Low Countries. 1 (2): 231–272. doi:10.18352/emlc.26. ISSN 2543-1587. S2CID 158696047.

- ^ a b "The World's Largest Living History Museum". The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 2023. Retrieved 20 Nov 2023.

- ^ Welch, Justine Parry; Conrad Jr., Robert J. (29 December 2021). "Taking Center Stage: The Virginia Revival Model Courtroom". Judicature. 105 (3). Duke Law School Judicial Institute.

- ^ Neal, Charles (19 January 2022). "Were Early American Prisons Similar to Today's?". American Prison Newspapers 1880–2020. JSTOR Daily.

- ^ Loth, Calder (30 Nov 2011). "Flemish Bond: A Hallmark of Traditional Architecture". Institute of Classical Architecture and Art.

- ^ Baye, Benjamin (2023). "Christopher Wren". Georgian Cities. Université de Paris-Sorbonne.

KSF

KSF