County of Lippe

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

County of Lippe Lippe-Detmold Grafschaft Lippe (German) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1413–1789 | |||||||||

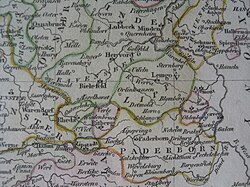

The County of Lippe in the late 18th century | |||||||||

| Status | Allod (to 1528/9) County (1528/9-1789) | ||||||||

| Common languages | German, Low German | ||||||||

| Religion | Largely Lutheran from c. 1500; Calvinist from 1615 | ||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | ||||||||

| Edler Herr, Count | |||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval Europe | ||||||||

• Established | 1413 | ||||||||

• Raised to principality | 1789 | ||||||||

| Currency | Taler (from 1752) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Germany | ||||||||

The County of Lippe (German: Grafschaft Lippe) or Lippe-Detmold was an Imperial Estate of the Holy Roman Empire. It had its origins in a small lordship on the Lippe river, first attested in 1123, and lands leased from the Bishopric of Paderborn from 1173. In the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, the lords of Lippe founded several cities (Lippstadt, Lemgo, Horn, Blomberg, and Detmold), the earliest city-foundations in Westphalia. The territory achieved Imperial immediacy in 1413 at the latest and was part of the Lower Rhenish–Westphalian Circle from 1512. In 1528 or 1529, it was promoted to the status of Imperial County and became part of the College of Lower Rhenish-Westphalian Imperial Counts in the Imperial Diet. Lippe was a centre of conflict during the Reformation as Count Simon V attempted to prevent Protestantism from spreading within his territory by force. Lutheranism was adopted in 1538, two years after his death. Simon VI converted to Calvinism in 1605, leading to a prolonged conflict with Lemgo, which eventually remained Lutheran. On his death in 1613, Simon VI left substantial lands and rights to his younger sons, who formed junior lines: Lippe-Brake and Lippe-Alverissen (which inherited Schaumburg-Lippe in 1644), while the main line became known as Lippe-Detmold. The Counts' efforts to centralise the state and expand its military and bureaucracy in the eighteenth century were stymied by the power of the junior lines and the nobility. In 1789 it became the Principality of Lippe.

History

[edit]Lordship of Lippe to 1528

[edit]The first documentary evidence for Lippe is a deed of 1123, naming Lord Bernard I as Bernhardus de Lippe. Later documents name him and his brother Herman as joint-rulers. "De Lippe" refers to the Lippe river and "Hermelinghof" ("Herman's Court") in the modern suburb of Lippstadt was located on the river's bank.

The lords leased the majority of modern Lipperland from Evergis, Bishop of Paderborn in 1173, after their uncle Freiherr Werner von Brach became a monk, handed his possessions over to Gehrden Abbey and returned the territory that he had leased to Evergis. This territory probably encompassed the area around Lemgo, Detmold, Lage, and Horn, since the Paderborn Prince-Bishops are recorded as the liege lords of this area in later documents.[1][2]

Bernhard II, son of Hermann I, managed to get sovereign rights for the House of Lippe. In 1185, he founded Lippstadt near his allod. This was the first city foundation of the High Middle Ages in Westphalia. To connect Lipperode and Lipperland, he acquired the Lordship of Rheda in 1190. Around the same year he founded Lemgo, the oldest city in the modern Lippe district. Bernhard II's grandson, Bernhard III confirmed the rights of Lemgo in 1245 and founded the cities of Horn (before 1248), Blomberg (before 1255), and Detmold (1263).

Between 1332 and 1358, the lords of Lippe acquired large parts of the County of Schwalenberg in the southeast and extended their possessions northwards up to the Weser river, through the acquisition of Varenholz and Langenholzhausen. The lordship reached its greatest territorial extent under Simon I (1275-1344).

After the death of Simon I in 1344, the lordship was divided. The portion "on this side of the forest" (diesseits des Waldes) was ruled by Simon I's son Otto and then his son, Simon III (1365-1410). The portion "on the other side of the forest" (jenseits des Waldes) went to Otto's brother Bernhard V. When Bernhard III died without a male heir in 1365, Simon III hoped that this portion would return to him, since at the partition in 1344 it had been agreed that in the event of one of the brothers dying without heirs "the lordship should come once more into the hands of the legal heir"). However Count Otto VI of Tecklenburg also claimed the legacy as the son-in-law of Bernhard V, leading to a long-running feud over Rheda and Lipperode that only concluded in 1401. In the end, Rheda went to Tecklenburg. Lippstadt was the subject of a conflict with the County of Mark, but around the mid fifteenth century they managed to make it a Samtherrschaft or shared administrative area (from 1666 to 1850, administration was shared with Brandenburg-Prussia).

Alongside this, Simon III attempted to prevent further divisions of the lordship. On 27 December 1368, the Burgmannen (castellans) of the lordship's castles and representatives of the cities of Horn, Detmold, and Blomberg agreed a Pactum unionis (unity pact), according to which they would all recognise the overlord that Lippstadt and Lemgo (the most important cities of the lordship) had agreed to.

Simon III's reign lasted until 1410. In 1400, he brought the cities of Barntrup and Salzuflen, and Sternberg Castle under his control through a mortgage. The rest of the County of Sternberg followed in 1405. However, his attempt to take over the County of Everstein through an inheritance alliance was unsuccessful. At the end of the Everstein feud with the Dukes of Brunswick-Lüneburg in 1408, Everstein fell to Brunswick-Lüneburg.

Bernhard VII (1430-1511) was even more unfortunate in his conflicts. He inherited the lordship at the age of one and was under the guardianship of the Archbishop of Cologne in his role as Duke of Westphalia. He opposed the Archbishop in the Soest Feud, leading to the destruction of Bernhard's capital, Blomberg, and of Detmold. Lemgo and Horn were spared on payment of a ransom.[3] In addition, he had to surrender part of his lordship to Hesse, receiving them back as hereditary fiefs and becoming a vassal of the Hessian Landgraves.

Promotion to county, Reformation

[edit]The enfiefment to Hesse played an important role in the following period, when Lutheranism began to spread in Lippe during the reign of Simon V. This took place against the will of Simon V, who remained a Roman Catholic throughout his life. However, Simon V was vassal to two liege lords: the Prince-Bishops of Paderborn, who were Catholic, and Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, who had been Lutheran since 1524. Simon's freedom of action was therefore limited. The spread of Lutheranism was encouraged by the strong position of the cities, especially Lippstadt and Lemgo.

The first contact with Lutheranism was probably the reading of Martin Luther's 95 Theses in Lemgo in 1518 - only a year after their original publication. In the following year, Lutheranism grew consistently in the city. Lemgo citizens attended Lutheran services in Herford. Protestant songs were sung in Lemgo before and after the mass. During a fasting period in 1527, some Lemgo citizens openly ate meat. In 1530 open conflict broke out with the rulers: Protestant songs were sung during the Catholic Easter mass. Simon V was furious and spoke of "rebellious farmers, who don't want to acknowledge any authority over them." Philip of Hesse encouraged the Lemgo citizens to pay compensation to Simon. In the midst of this, in 1528, Simon V was granted the title of Imperial count. Lippe became one of around 140 Imperial counties.

After 1532, Lutheranism spread in the other cities as well. When Simon V sought support for a military expedition against Lemgo in 1533, Philip of Hesse intervened as mediator. In the same year, Lemgo adopted the Braunschweig Church Order and officially became Lutheran. In 1535, Simon V and Duke John III of Cleves attacked Lippstadt, which had also become Lutheran. The city surrendered to its liege lords. Fear of military intervention grew in Lemgo as well, but Philip's continued mediation prevented this.

Simon V died in 1536. His son Bernhard VIII (1536-1563) was a minor and was entrusted to three legal guardians - two Catholics and one Protestant. However, Jobst II of Hoya, one of the Catholic guardians, converted to Protestantism in 1525. In response to Anabaptist activity, Philip encouraged a religious renewal in Lippe at the beginning of 1538. Following a series of five assemblies at Cappel, the cities and nobility decided to introduce a Protestant church order for Lippe, which was completed on 15 September 1538. Lippe was caught up in the Schmalkaldic War (1546-1547), in which the Protestant side was defeated.

The second stage of the reformation in Lippe, the conversion to Calvinism, was the personal work of Simon VI (1563-1613), one of Lippe's most influential and effective rulers. Multifaceted and curious, he probably mastered most aspects of contemporary scholarship, as shown by Tycho Brahe's gift to him of a magnificent copy of his star catalogue, Astronomiae instauratae mechanica. The Count's extensive library was the basis of the modern Lippe State Library. The Emperor entrusted him with many diplomatic missions.

Theologically, Simon VI inclined towards Calvinism, which was spreading in the Palatinate, Saxony, and neighbouring Hesse. He increasingly encouraged the faith in Hesse as well. "The... methods by which the general resistance was broken were good debating, instruction, admonition, removal from office, and employment of Reformed priests."[4] The conversion of Lippe to Calvinism is generally dated to 1605, when Simon VI first took the reformed eucharist (with wine and bread rather than wafers). Simon's efforts failed to sway the city of Lemgo, which remained Lutheran. This led to a long, bitter conflict, which continued under Simon's successors and even saw Lemgo attack the county's castle at Brake. Finally, the conflict was ended by the Röhrentruper Recess in 1617, which allowed Lemgo to remain Lutheran.

Thirty Years' War

[edit]Simon VI's death in 1613 had wide-ranging consequences for Lippe's history. Although he had adopted primogeniture in 1593, he provided substantial compensation for his younger sons through paréage (recognition of joint sovereignty). This was further expanded with additional rights, like the right to homage or consultation before the calling of a Landtag. Until well after the end of the Holy Roman Empire, there were numerous processes that were shared between the ruling Detmold line, descended from Simon VII and the younger lines of Lippe-Brake and Lippe-Alverdissen, descended from Otto and Philip I respectively.

The Alverissen line gained control of part of the County of Schaumburg in 1644 and founded Schaumburg-Lippe, which had Imperial immediacy like Lippe itself. The younger lines were able to safeguard their interests particularly well because of numerous changes of ruler (1627, 1636, 1650, and 1652) and regencies (1627-1631 and 1636-1650) in the main Detmold line.

During the Thirty Years' War, Lippe itself did not belong to either faction, but had clear sympathies. At the beginning of the war, Christian "the Cool" of Brunswick marched through Lippe on his way to attack Paderborn, as did the Imperial army under Tilly, which was sent to stop him. The Count had to billet soldiers from both sides. In the following years, Lippe suffered from heavy war taxes, the occasional passage of armies, and increasing brigandage.

The last years of the war were particularly hard for Lippe. In 1634, Swedish troops encamped at Minden, while Imperial troops held Paderborn, with Lippe stuck in between. Lemgo was taken and sacked by the Swedes twice and the whole county suffered from raids and plundering. By the end of the war the cities of Lippe had lost around two thirds of their population; the rural population was reduced by around 50%. Lippe paid about two million Imperial talers in war taxes, two thirds coming from Lemgo alone.

Baroque and Enlightenment

[edit]

The period after the Thirty Years' War in Lippe was characterised by moves towards the centralisation of the administration. This tendency clashed with some particular features of Lippe in the Baroque period.

Firstly, the tiny size of the territory, which prevented any expansion of Lippe's military or diplomatic influence. However, this did not prevent Frederick Adolphus (r. 1697-1718) from seeking this influence. While Lippe met its military obligations to the Empire in the period up to 1697 through the payment of subsidies, Frederick Adolphus managed to establish a Lippe company, which was then built up to battalion strength, exceeding the size required by the Empire. The small troop was only actually put to use to extend Lippe's influence once, in 1776, when Count Simon August (r. 1734-1782) ordered a troop of thirty men occupy Gemen castle in order to increase Lippe's influence over the County of Gemen. However, the forces were captured by the captain of the castle with the help of some farmers.

A second challenge was the wide range of privileges which Simon VI's will had left to the other lines. Until 1709, the main conflicts were with the Brake line, which opposed Count Frederick Adolphus' aspirations to an absolute monarchy. In 1705, Lippe-Brake even concluded a protection treaty with Prussia and attempted to separate Brake's administration off from Lippe altogether. This came to an end with the extinction of the Brake line in 1709. Conflict continued with the Alverdisser line, which also controlled the independent County of Schaumberg-Lippe. The recruitment and fortification measures of William, Count of Schaumburg-Lippe (r. 1748-1777) often contravened Lippe's military sovereignty. There were several court cases before the Reichshofgericht and the Reichskammergericht on this and other questions.

The third issue, which was a typical problem for the development of absolutism outside Lippe as well, was the power of the nobility. In Lippe this mainly meant the right of the nobles to participate not just in the approval of laws, but also in levying, raising, and even spending taxes. In the face of these rights, the only possibility open to the Lippe counts was obstructionism. They sought to replace regular parliaments with the so-called Kommunikationstage ("communication days"), at which real conclusions could not be reached. Frederick Adolphus gave up on calling assemblies of nobles at all. In 1712, he banned the noble assembly from gathering on its own initiative. However, towards the end of his reign, he was prevailed upon to call the assembly again, since his shortage of money could not otherwise be solved. His successors were not able to abandon co-governance with the landed nobility. The unbroken power of the nobility remained an issue for the modernisation of the country in the 19th century.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Diether Pöppel: Das Hochstift Paderborn – Entstehung und Entwicklung der Landeshoheit. Paderborn 1996, p. 54.

- ^ G.J. Rosenkranz, "Die Verfassung des ehemaligen Hochstifts Paderborn in älterer und späterer Zeit." WZ 12, 1851, pp. 1–162, p. 80.

- ^ Linde, Roland (2005). Das Rittergut Gröpperhof: Höfe und Familien in Westfalen und Lippe. Vol. 2. p. 20.

- ^ Kittel

Bibliography

[edit]- Neithard Bulst (ed.): Die Grafschaft Lippe im 18. Jahrhundert. Bevölkerung, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft eines deutschen Kleinstaates. Bielefeld 1993, ISBN 3-89534-102-9.

- Hans Kiewning: Die auswärtige Politik der Grafschaft Lippe vom Ausbruch der französischen Revolution bis zum Tilsiter Frieden. Detmold 1903.

- Hans Kiewning: Lippische Geschichte. Bis zum Tode Bernhards VIII. Detmold 1942.

- Jürgen Miele: Das Lippische Hofgericht 1593–1743. Ein Beitrag zu Entstehungsgeschichte, Gerichtsverfassung und Prozessverfahren des zivilen Obergerichts der Grafschaft Lippe unter Berücksichtigung reichsgesetzlicher Bestimmungen. Göttingen 1984.

- Neumann, Wolfgang J. (2008). Der lippische Staat. Woher er kam – wohin er ging. Lemgo: Neumann. ISBN 978-3-9811814-7-0.

- Peter Nitschke: Verbrechensbekämpfung und Verwaltung. Die Entstehung der Polizei in der Grafschaft Lippe 1700–1814. Münster 1990, ISBN 3-89325-040-9.

- Heinz Schilling: Konfessionskonflikt und Staatsbildung. Eine Fallstudie über das Verhältnis von religiösem und sozialem Wandel in der Frühneuzeit am Beispiel der Grafschaft Lippe. Gütersloh 1981, ISBN 3-579-01675-X.

- Gisela Wilbertz (ed.): Hexenverfolgung und Regionalgeschichte. Die Grafschaft Lippe im Vergleich. Bielefeld 1994, ISBN 3-89534-109-6.

KSF

KSF