Curly (scout)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

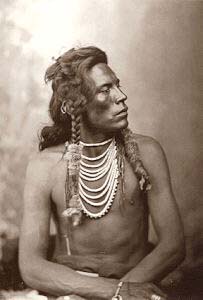

Ashishishe (c. 1856 – 1923), known as Curly (or Curley) and Bull Half White, was a Crow scout in the United States Army during the Sioux Wars, best known for having been the last member of Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer's battalion to depart Custer's detachment before its annihilation at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. He did not participate in Custer's final fight, but may have watched from a distance, and was the first to report the defeat of the 7th Cavalry Regiment. Afterward a legend grew that he had been an active participant and managed to escape, leading to conflicting accounts of Curly's involvement in the historical record.

Life

[edit]Ashishishe was born in approximately 1856 in Montana Territory, the son of Strong Bear (Inside the Mouth) and Strikes By the Side of the Water. His name, variously rendered as Ashishishe, Shishi'esh, etc., has been said to literally mean "the crow",[1] however, this may be a misunderstanding as the Crow word for "crow" is "áalihte".[2] Ashishishe may be a transliteration of the word "shísshia", which means "curly".[3] His death record lists his name as being "Bull Half White (Curly)".[4] He resided on the Crow Reservation in the vicinity of Pryor Creek, and married Bird Woman. He enlisted in the U.S. Army as an Indian scout on April 10, 1876. He served with the 7th Cavalry Regiment under George Armstrong Custer, and was with them at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in June of that year, along with five other Crow warrior/scouts: White Man Runs Him, Goes Ahead, Hairy Moccasin, his cousin White Swan, and Half Yellow Face, the leader of the scouts. Custer had divided his force into four separate detachments, keeping a total of 210 men with him. Half Yellow Face and White Swan fought alongside the soldiers of Reno's detachment, and White Swan was severely wounded. Curly, Hairy Moccasin, Goes Ahead and White Man Runs Him went with Custer's detachment, but did not actively participate in the battle; they later reported they were ordered away before the intense fighting began. Curly separated from White Man Runs Him, Hairy Moccasin, and Goes Ahead, and he watched the battle between the Sioux/Cheyenne forces and Custer's detachment from a distance. Seeing the complete extermination of Custer's detachment, he rode off to report the news.[1]

A day or two after the battle, Curly found the Far West, an army supply boat at the confluence of the Bighorn and Little Bighorn Rivers. He was the first to report the 7th's defeat, using a combination of sign language, drawings, and an interpreter. Curly did not claim to have fought in the battle, but only to have witnessed it from a distance; since this first report was accurate,[1] two of the most influential historians of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Walter Mason Camp (who interviewed Curly on several occasions) and John S. Gray, accepted Curly's early account. Later, however, when accounts of "Custer's Last Stand" began to circulate in the media, a legend grew that Curly had actively participated in the battle, but had managed to escape. Later on, Curly himself stopped denying the legend, and offered more elaborate accounts in which he fought with the 7th and had avoided death by disguising himself as a Lakota warrior, leading to conflicting accounts of his involvement.[1] The family story is that he was involved, but when he saw Custer fall, he gutted open a horse and hid inside.

After the Crow Agency had been moved to its current site in 1884, Curly lived there, on the Crow Reservation on the bank of the Little Bighorn River, very close to the site of the battle. He served in the Crow Police. He divorced Bird Woman in 1886, and married Takes a Shield. Curly had one daughter, Awakuk Korita ha Sakush ("Bird of Another Year"), who took the English name Dora.[5] For his Army service, Curly received a U.S. pension as of 1920.

He died of pneumonia in 1923, and his remains were interred in the National Cemetery at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, only a mile from his home.[1][6]

Curly's story

[edit]Curly's earliest newspaper account as recorded in the Helena (Montana) Weekly Herald on July 20, 1876, is as follows:

Custer, with his five companies, after separating from Reno and his seven companies, moved to the right around the base of a hill overlooking the valley of the Little Horn, through a ravine just wide enough to admit his column of fours. There was no sign of the presence of Indians in the hills on that side (the right) of the Little Horn, and the column moved steadily on until it rounded the hill and came in sight of the village lying in the valley below them. Custer appeared very much elated and ordered the bugle to sound a charge, and moved on at the head of his column, waving his hat to encourage his men. When they neared the river the Indians, concealed in the underbrush on the opposite side of the river, opened fire on the troops, which checked the advance. Here a portion of the command were dismounted and thrown forward to the river, and returned the fire of the Indians.

During this time the warriors were seen riding out of the village by hundreds, deploying across his front to his left, as if with the intention of crossing the stream on his right, while the women and children were seen hastening out of the village in large numbers in the opposite direction.

During the fight at this point Curley saw two of Custer's men killed, who fell into the stream. After fighting a few moments here, Custer seemed to be convinced that it was impracticable to cross, as it only could be done in column of fours exposed during the movement to a heavy fire from the front and both flanks. He therefore ordered the head of the column to the right, and bore diagonally into the hills, downstream, his men on foot leading their horses. In the meantime the Indians had crossed the river (below) in immense numbers, and began to appear on his right flank and in his rear; and he had proceeded but a few hundred yards in the direction the column had taken, when it became necessary to renew the fight with the Indians who had crossed the stream.

At first the command remained together, but after some minutes' fighting, it was divided, a portion deployed circularly to the left, and the remainder similarly to the right, so that when the line was formed, it bore a rude resemblance to a circle, advantage being taken as far as possible of the protection afforded by the ground. The horses were in the rear, the men on the line being dismounted, fighting on foot. Of the incidents of the fight in other parts of the field than his own, Curley is not well informed, as he was himself concealed in a ravine, from which but a small portion of the field was visible.

The fight appears to have begun, from Curley's description of the situation of the sun, about 2:30 or 3 o'clock p.m., and continued without intermission until nearly sunset. The Indians had completely surrounded the command, leaving their horses in ravines well to the rear, themselves pressing forward to attack on foot. Confident in the superiority of their numbers, they made several charges on all points of Custer's line, but the troops held their position firmly, and delivered a heavy fire, and every time drove them back. Curley said the firing was more rapid than anything he had ever conceived of, being a continuous roll, as he expressed it, "the snapping of the threads in the tearing of a blanket. The troops expended all the ammunition in their belts, and then sought their horses for the reserve ammunition carried in their saddle pockets.

As long as their ammunition held out, the troops, though losing considerable in the fight, maintained their position in spite of the efforts of the Sioux. From the weakening of their fire toward the close of the afternoon, the Indians appeared to believe their ammunition was about exhausted, and they made a grand final charge, in the course of which the last of the command was destroyed, the men being shot where they lay in their position in the line, at such close quarters that many were killed with arrows. Curley says that Custer remained alive through the greater part of the engagement, animating his men to determined resistance; but about an hour before the close of the fight, he received a mortal wound.

Curley says the field was thickly strewn with dead bodies of the Sioux who fell in the attack, in number considerably more than the force of soldiers engaged. He is satisfied that their loss will exceed six hundred killed, beside an immense number wounded.

Curley accomplished his escape by drawing his blanket around him in the manner of the Sioux and passing through an interval which had been made in their lines as they scattered over the field in their final charge. He says they must have seen him, for he was in plain view, but was probably mistaken by the Sioux for one of their number, or one of their allied Arapahos or Cheyennes.

The most particulars of the account given by Curley of the fight are confirmed by the position of the trail made by Custer in his movements, and the general evidence of the battle field.

Only one discrepancy is noted, which relates to the time when the fight came to an end. Officers of Reno's command, who, late in the afternoon, from high points, surveyed the country in anxious expectation of Custer's appearance, and commanded a view of the field where he had fought, say that no fighting was going on at that time, between 5 and 6 o'clock. It is evident, therefore, that the last of Custer's command was destroyed at an earlier hour in the day than Curley relates.

Thomas Leforge, in his autobiographical narrative, stressed that the Army expected scouts to be non-participant in skirmishes and added this recollection:

I interpreted for Lieutenant Bradley when he interviewed Curly [sic], several days after the Custer battle had occurred. He was spoken of then as the 'sole survivor' of the disaster. But he himself did not lay claim to that kind of distinction. On the contrary, again and again during the long examination of him by Bradley, the young scout said, 'I was not in the fight.' When gazed upon and congratulated by visitors he declared, 'I did nothing wonderful; I was not in it. He told us that when the engagement opened he was behind, with other Crows. He hurried away to a distance of about a mile, paused there, and looked for a brief time upon the conflict. Soon he got still farther away, stopping on a hill to take another look. He saw some horses running away loose over the hills. He turned back far enough to capture two of the animals, but later he decided they were an impediment to his progress away from the Sioux, so he released them. He told me he directed his course toward Tulloch's Fork and came down the same trail I had come down on another occasion with Captain Bull and Lieutenant Rowe.

Romantic writers seized upon Curly as a subject suited to their fanciful literary purposes. In spite of himself, he was treated as a hero. He took no special pains to deny the written stories of his unique cunning. He could not read, he could speak only a little English, and it is likely he knew of no reason why he should make any special denial. The persistent claim put forward for him by others, but as though it came direct from him, brought upon him from some of the Sioux the accusation, 'Curly is a liar; nobody with Custer escaped us.' But he was not a liar. All through his subsequent life he modestly avowed from time to time what he did to Bradley, 'I did nothing wonderful; I was not in the fight.' I knew him from his early boyhood until his death in early old age. He was a good boy, an unassuming and quiet young man, a reliable scout, and at all times of his life he was held in high regard by his people.

— Leforge, Memoirs of a White Crow Indian, 1928 edition, p. 250.

See also

[edit]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Kessel and Wooster, p. 105.

- ^ "Crow Dictionary". dictionary.crowlanguage.org. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- ^ "Crow Dictionary". dictionary.crowlanguage.org. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- ^ Family Search

- ^ "Curly, a Crow Scout: Finding My Ancestors in a Center Photograph". Buffalo Bill Center of the West. 2017-10-19. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- ^ "Helena weekly herald. [volume] (Helena, Mont.) 1867-1900, July 20, 1876, Image 1". Herald Print. Co. 4 August 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

References

[edit]- Gray, John S. Custer's Last Campaign: Mitch Boyer and the Little Bighorn Reconstructed Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1991.

- Hammer, Ken. With Custer in '76. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976.

- Kessel, William B.; Robert Wooster (2005). Encyclopedia of Native American wars and warfare. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 0-8160-3337-4. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- Nichols, Ron. Men with Custer. Hardin: Custer Battlefield Historical and Museum Association, 2000.

External links

[edit]- "Montana Medicine Show: Curly," KGLT, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (WGBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed September 14, 2016, Accessible only in the US.

KSF

KSF