Cynical Theories

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

| |

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Published | August 25, 2020 |

| Publisher | Pitchstone Publishing |

| Publication place | United States |

| ISBN | 978-1-63431-202-8 |

| Website | cynicaltheories |

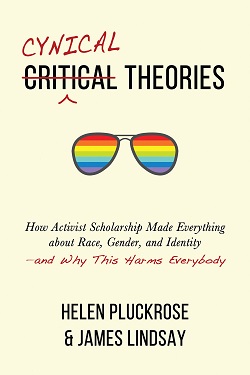

Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything About Race, Gender, and Identity—and Why This Harms Everybody is a nonfiction book by Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay, published in August 2020. The book was listed on the bestsellers lists of Publishers Weekly,[1] USA Today,[2] and the Calgary Herald.[3]

The book was released in Australia as Cynical Theories: How Universities Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity – and Why This Harms Everybody.[4][5]

Summary

[edit]Cynical Theories contrasts the academic approaches of liberalism and postmodernism, then argues that "applied postmodernism" (which focuses on ought rather than is) has displaced other approaches to activism and scholarship. The authors present several academic fields and schools—postcolonial theory, queer theory, critical race theory, intersectionality, fourth-wave feminism, gender studies, fat studies, and ableism—and describe how the "applied postmodernism" approach has developed in each field. The authors use capitalization to distinguish between the liberal concept of "social justice" and the ideological movement of "Social Justice" that they state has reified postmodernism.

Sales and rankings

[edit]Shortly after its release the book became a Wall Street Journal, USA Today,[6][7] and Publishers Weekly bestseller and a number-one bestseller in philosophy on Amazon.[citation needed] Cynical Theories was named in the Financial Times' Best Books of the Year 2020[8] and in The Times' Best Political and Current Affairs Books of the Year 2020.[9]

Critical reception

[edit]Positive

[edit]Harvard University's Steven Pinker, a psychologist and public intellectual, praised the book, saying that it "exposes the surprisingly shallow intellectual roots of the movements that appear to be engulfing our culture".[10]

Douglas Murray wrote an admiring review of Cynical Theories for The Times, saying "I have rarely read such a good summary of how postmodernism evolved from the 1960s onwards." Murray concluded, "Yet as I put down the book and turned on the news I couldn't help thinking that this deconstruction of the deconstructionists may have arrived just a moment too late."[11]

Joanna Williams, writing from her post as a commentator on Spiked, said that the authors provide "a huge service in translating the language of today’s activists and explaining to readers not steeped in critical theory or postmodernism how the world looks from the perspective of those who are," and that it "successfully draws out how, over the course of six decades, the burgeoning popularity of critical theory within university humanities and social-science faculties shifted postmodernism from a minority academic pursuit to an all-encompassing political framework." But Williams also noted that "[w]hile Cynical Theories offers an excellent account of how postmodern scholarship morphed into social-justice activism, it is less persuasive when it comes to why this happened." Williams stated, "What's largely missing from Cynical Theories is a broader political contextualisation of social-justice activism."[12]

Ryan Whittaker wrote on The Manchester Review that "Despite its flaws, Cynical Theories is an important, interesting, accessible, and extensively cited work of non-fiction. It avoids the pitfalls of texts caught up in 'culture war' subjects; it intentionally avoids screeds of left- and right-wing punditry and the reader is likely to come away feeling that it has been academic and fair towards its opponents.[13] Peter Gregory Boghossian who had also published bogus articles in the Grievance studies affair with Lindsay and Pluckrose stated that the book "is a tactical nuclear strike on the heart of the moral architecture that is sustaining Culture war 2.0" and "will take the culture war to the next level".[14][additional citation(s) needed]

Writing in The Times Literary Supplement, Simon Jenkins wrote that within half an hour of starting he thought he had "had enough of this book. Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay seemed obsessed by a straw man, a fake foe. Their opponents, I felt, were surely well-intentioned and did not really believe what they were accused of believing." He went on, however, "I read on and now think differently." He cited the conclusion "refreshing" in that they offered no "counter-revolutionary strategy" or "demand that Theory be suppressed," but rather only call for the support of "reason, debate, tolerance, democracy and the rule of law." He wrote that the book illuminates "one of those sidetracks in Western ideology that led to both Salem and Weimar."[15]

Mixed

[edit]Nigel Warburton, writing for The Spectator, praises the early chapters on postmodernism and calls the first part of the book "a plausible and interesting story about the origins of the phenomena they describe. Like Roger Scruton in his book Fools, Frauds, and Firebrands, they have done their homework, and can't fairly be accused of a superficial understanding of the thinkers they engage with, though they probably underestimate the seriousness and depth of Foucault's analysis of power." He says "the book then becomes a gloves-off polemic against specific manifestations of Theory in areas such as postcolonialism, queer theory, critical race theory, gender, and disability studies. Here they are far less charitable to their targets, and they take cheap shots in passing, a strategy likely to prevent anyone who has caught Theory from being cured by reading this."[5]

Nick Fouriezos of OZY magazine described Cynical Theories as the first cohesive attempt to tie together the intellectual strands of the intellectual dark web

. He notes that [w]hile crediting liberalism for leading to the gains of the modern feminist movement, LGBT rights and the civil rights movement, [the book] suggests almost total victory was reached in those fields by the end of the 1980s

while ignoring significant issues that have persisted since then.[14]

Reviewing the book for Philosophy Now, Stephen Anderson noted a "major weakness" in the book yet recommended a reading.[note 1][16]

La Trobe University ethicist Janna Thompson wrote on The Conversation that the book's authors are right to point out

the unjustified harm to individuals who are called out and “cancelled” for minor misdemeanours, or for stating a view that identity activists deem unacceptable

but noted that one does not have to be a relativist to think the opinions [...] of [...] minority groups ought to be respected

or be "anti-science" to think scientific research sometimes ignores [...] perspectives of women and minorities.

She wrote that [l]iberals — as advocates of critical engagement — should be open to the possibility that Theory, despite faults, has detected forms of prejudice our society tends to overlook.

Drawing on political scientist Glyn Davis's arguments, Thompson noted that the most problematic aspect

of the book is the blame it heaps on humanities departments of universities for stirring up a cancel culture and the culture wars

. Thompson stated that Lindsay and Pluckrose, by overstating their case and aiming their weapons at humanities and universities

, cannot pass themselves off as objective contributors to a search for truth

, and betrayed that they themselves were combatants in the culture wars

.[17]

Brian Russell Graham of Aalborg University[18] and contributor for Quillette[18][19][note 2] and Areo Magazine[18][19][note 3] wrote that Cynical Theories "deserves all the plaudits it is getting, but it could perhaps have been an even better book." He cited the "1960s homegrown American political activism, which burgeoned partly independently of European developments" as "the most salient" omission in the book. He wrote that "In the United States, identity politics began to assert itself before and without the influence of Foucault and, more generally, the postmodernist" role in "the so-called 'cultural turn'".[20]

Writing for the American conservative James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, Sumantra Maitra stated that Cynical Theories provides "example upon example as evidence" that "academic institutions [...] changed over time" and "how everything, from media to research, seems like ideological propaganda". Maitra asserts that "Postmodernism is also, at the end of the day, a vicious power play. The entire “decolonizing” movement is, likewise, essentially a way to “bolster their ranks” in the academy". However, after noting that Lindsay and Pluckrose were "bafflingly opposed to funding cuts" because of their avowed resistance to the temptation to "fight illiberalism with illiberalism or counter threats to freedom of speech by banning the speech of the censorious", Maitra concedes that the book "offers vague utopian wishes" to counter the "problem", because

If [...] post-modernism is dangerously subversive [...] then that threat would not be won in “the marketplace of ideas,” given that the levers of such ideas are controlled by the same people with whom one is battling (as Lindsay correctly points out himself)[...] Power is tackled with power, not just ideas and values. For all their faults, the post-modernists, like the Marxists, understand the question of power far better than liberals, and are willing to use it for political ends.[21]

Roland Rich in the Population Council's Population and Development Review wrote that the authors "have done their research" yet "did not begin their enquiry with an open mind". Reading amidst the "dispute over the 2020 [American presidential] election results", Rich shifted away from his "initial instinct" to "pile on" the "social justice perspective". Yet he credited the book for its unintended remedy to the "conservative media" tactic of derogatorily lumping together liberal "progressive thinking" and "critical theory" since the book disentangled the two by preferring the former to the latter. Rich concluded that "Pluckrose and Lindsay have taken sides in this debate, but it is almost impossible not to do so."[note 4][22]

Negative

[edit]Tim Smith-Laing wrote in conservative newspaper The Daily Telegraph that the authors "leap from history to hysteria". Describing the hoaxes cited in the book, Smith-Laing asserted that it was "not quite logical to assert that your hoax shows a widespread disregard for empirical proof when the papers published contained quantities of carefully fabricated empirical proof". Additionally, he wrote that "restricted claims that writers such as Jacques Derrida or Richard Rorty make [...]do not add up to anything like Pluckrose and Lindsay’s apocalyptic characterisations". He said that though he believed the book presents an acceptable sketch of the history of several of the intellectual strains it highlights, it nevertheless

fails on its own terms: not because the values of rational, evidence-based argument that Pluckrose and Lindsay claim to stand for are poor values, but because the book itself so transparently does not fulfill them. You could be forgiven for wondering who the real cynics are here.[23]

Park MacDougald, writing from his post as Life & Arts editor of the conservative Washington Examiner, commented that "the specific form of “reified postmodernism” now promoted by our elites has very little to do with, say, Derrida’s interest in the aporias of language". MacDougald wrote that Lindsay and Pluckrose, with their "cursory attempt to “prove” that rights-based liberalism is somehow more objectively true than other political theories", fail to understand that

most social and political “truths” are not established by proof or equation. They are narratives, and it is impossible to understand which ones get accepted [...] without thinking about “systems of power and hierarchies.” [note 5]

MacDougald concluded, "I sympathize with Pluckrose and Lindsay’s frustration at how the woke Left uses a bastardized version of postmodernism to justify petty intellectual tyranny [...] But it is a mistake simply to dismiss the postmodernists for deviating from the true faith of evidence-based liberalism."[24]

Dion Kagan on The Monthly noted the book's "well-worn approach" in its dismissal of certain academic fields, along with its "omissions, misattributions and cherrypicking". Kagan also conceded that "Cynical Theories isn't quite Jordan Peterson–level caricature of postmodernism".[4]

See also

[edit]- Culture war – Conflict between cultural values

- Exiting the Vampire Castle – 2013 political essay by Mark Fisher

- Reverse post-material thesis – Academic theory regarding far-right politics

- Paradox of tolerance – Logical paradox in decision-making theory

Notes

[edit]- ^ He cites how the key development at the turn of the 21st century which led the authors to write their critique "was that ordinary people, not just academics, began to take to heart the assumptions of postmodern academics." Anderson, however, notes a "major weakness" in the book: "Lindsay and Pluckrose seem to imply that secular rationalism, the scientific method, and the idea of human rights, leapt into existence ex nihilo [...] as a pure gift of the Enlightenment, without social conditions or progenitors [...] [W]hile it is quite fair for Lindsay and Pluckrose to criticise postmodernism for arbitrarily exempting its own metanarrative from being critically deconstructed, the very same charge of ‘historical denial’ could be leveled against [Lindsay and Pluckrose] in return".

Anderson continued that "If, as [Pluckrose and Lindsay] insist, modernism itself gave rise to the conditions that produced postmodernism and Critical Theory, then it’s hard to see how reversion to those same modernist values would be likely to fix anything." Nevertheless, Anderson concludes that the bookisn’t a hard book to read

andshould be read by anyone with a serious interest in the origins of today’s events in regard to the ideology of Social Justice. Every politician should have a copy. And it would do a lot of good in the Humanities courses of the (post)modern university if this book were required reading along with the various social justice texts they already make mandatory – not just to provide ideological balance, but because it contains a thorough and fair history of the whole movement, from a helicopter-view perspective.

- ^ Quillette articles have reportedly raised concerns about political correctness, freedom of speech in educational institutions, "postmodernism", and "critical theory".

- ^ Areo Magazine states that it supports "universal liberal humanism". Pluckrose herself was the editor-in-chief from June 2018–May 2021 of Areo. "About Areo". Archived from the original on November 16, 2022.

- ^ Rich acknowledged applied-postmodernist approaches' "policy utility" as "corrective device[s]" and "test[s] of policy ideas", which could demonstrate "critical theory to be other than cynical theory". But Rich simultaneously remarked that "[t]he woke" themselves may dismiss such a defence as a mere "trick of the oppressors" which render the woke mere "commentators on policy choices", preferring instead "to dominate the debate in academia, and to empower activists on the ground". Rich inferred that applied postmodernism and applied postmodernism's opponents lacked any "shared foundational premises". He therefore noted the impossibility of "compromise" or "middle ground" between applied-postmodernist "activists" and their opponents since both seek to "capture the entire scholarly discourse".

- ^ MacDougald argued that "[...] Anyone critical of the U.S. establishment, whether on the conservative Right or the socialist Left, understands this point instinctively" (emphasis in original), citing the media's viewing of "Trump’s collusion with Russia as real news" and "Hunter Biden’s misdeeds as fake news", and that "the expert consensus [...] tend to reflect whatever [...] upper-middle-class liberals believe".

References

[edit]- ^ "Publishers Weekly Best-Sellers". OANow.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "US-Best-Sellers-Books-USAToday". Martinsville Bulletin. Retrieved September 3, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Calgary bestsellers". Calgary Herald. August 29, 2020. p. B.7.

- ^ a b Kagan, Dion (November 10, 2020). "Cancel the woke: 'Cynical Theories'". The Monthly. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

The less philosophy-minded may find Cynical Theories wanting in terms of a broader political, economic and historical contextualisation of social-justice activism. For this, something like Jeff Sparrow's book Trigger Warnings, an account of the emergence of identity politics alongside the transition from direct to delegated politics, is more enlightening. As is Waleed Aly's recent analysis of cancel culture – and other moralistic, orthodox tendencies in woke politics – which is viewed in light of the difficulty liberalism has grappling with power and oppression, and disillusionment with the current practice of liberal democracy.

- ^ a b Warburton, Nigel. "Universities are supposed to encourage debate, not strangle it". The Spectator. No. November 14, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ "Bestselling Books Week Ended August 29". The Wall Street Journal. September 3, 2020. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ "US-Best-Sellers-Books-USAToday". The Washington Post. Associated Press. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ Rachman, Gideon (November 18, 2020). "Best books of 2020: Politics". Financial Times. Archived from the original on November 18, 2020. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ Millen, Roland White | Robbie. "Best political and current affairs books of the year 2020". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Paul Kelly (September 12, 2020). "Tracing the dangerous rise and rise of woke warriors". The Australian. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ Murray, Douglas (September 4, 2020). "Cynical Theories by Helen Pluckrose & James Lindsay review — woke warriors are conquering academia". The Times.

- ^ Williams, Joanna (August 28, 2020). "How wokeness conquered the academy". Spiked. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ Whittaker, Ryan (October 18, 2020). "Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay | Cynical Theories". The Manchester Review. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ a b Fouriezos, Nick (August 10, 2020). "American Fringes: The Intellectual Dark Web Declares Its Independence". OZY. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Jenkins, Simon. "The new intolerance". Times Literary Supplement. No. 2 October 2020. News UK. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Stephen (2021). "Cynical Theories by James Lindsay & Helen Pluckrose". Philosophy Now. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ Thompson, Janna (November 5, 2020). "Friday essay: a new front in the culture wars, Cynical Theories takes unfair aim at the humanities". The Conversation. Archived from the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Brian Russell Graham, Author at Areo".

- ^ a b "Brian Russell Graham". John Hunt Publishing.

- ^ Brian Russell Graham (February 4, 2021). "Review: Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay's "Cynical Theories"". Merion West. Archived from the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ Maitra, Sumantra (May 29, 2020). "A War Against 'Normal'". The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ Rich, Roland (March 16, 2021). "Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity-and Why This Harms EverybodyPitchstone Publishing, 2020. 352 p. $27.95". Population and Development Review. 47 (1): 264–267. doi:10.1111/padr.12393. S2CID 233831239.

- ^ Smith-Laing, Tim (September 19, 2020). "'Postmodernism gone mad': is academia to blame for cancel culture?". The Telegraph.

- ^ "Is postmodernism really worthless? | Review of Cynical Theories". Washington Examiner. December 18, 2020.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Ayaan Hirsi Ali. "The Flawed Premises of "Critical Theories" and the Risks for U.S. Foreign Policy" (PDF). Aspen Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2021.

KSF

KSF