David Urquhart

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

David Urquhart | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | David Urquhart Jr. 1 July 1805 Braelangwell, Cromarty, Scotland |

| Died | May 16, 1877 (aged 71) Clarens, Switzerland |

| Resting place | Clarens, Switzerland |

| Spouse | Harriet Angelina Fortescue (from 1854) |

| Children | David Urquhart of Braelangwell

Margaret Ann Urquhart William Urquhart Francis Fortescue Urquhart |

| Parents |

|

David Urquhart Jr. (1 July 1805 – 16 May 1877) was a British diplomat, writer and politician, serving as a Member of Parliament for Stafford from 1847 to 1852.[1] He also was an early promoter in the United Kingdom of the hammam (known to westerners as the "Turkish bath") which he came across in Morocco and Turkey .[2]

Early life

[edit]Urquhart was born at Braelangwell, Cromarty, Scotland.[1] He was the second son of Margaret Hunter and David Urquhart.[3] His father died while he was a boy.[3] Urquhart was educated, under the supervision of his widowed mother, in France, Switzerland, and Spain. Jeremy Bentham assisted with Urquhart's education.[3]

He returned to Britain in 1821 and spent a gap year learning to farm and working at the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich. In 1822, he attended St John's College, Oxford.[1] However, he left before completing college because of his poor health and, instead traveled to eastern Europe.[3] He never completed his classics degree as his mother's finances failed.

Career

[edit]Greece and Turkey

[edit]In 1827, Urquhart joined the nationalist cause and fought in the Greek War of Independence.[3] Seriously injured, he spent the next few years championing the Greek cause in letters to the British government, self-promotion that entailed his appointment in 1831 to Sir Stratford Canning's mission to Istanbul to settle the border between Greece and Turkey.[1]

Urquhart's principal role was to nurture the support of Koca Mustafa Reşid Pasha, intimate advisor to the Sultan Mahmud II. He found himself increasingly attracted to Turkish civilisation and culture, becoming alarmed at the threat of Russian intervention in the region. Urquhart's campaigning, including the publication of Turkey and its Resources, culminated in his appointment on a trade mission to the region in 1833.[1] He struck such an intimate relationship with the government in Istanbul that he became outspoken in his calls for British intervention on behalf of the Sultan against Muhammad Ali of Egypt in opposition to the policy of Canning. He was recalled by Palmerston just as he published his anti-Moscow pamphlet England, France, Russia and Turkey which brought him into conflict with Richard Cobden.[1]

In 1835, he was appointed secretary of embassy at Constantinople in the Ottoman Empire, but an unfortunate attempt to counteract Russian aggressive designs in Circassia, which threatened to lead to an international crisis, again led to his recall in 1837.[1]

Urquhart's position was so aggressively anti–Russian and pro–Turkish that it created difficulties for British politics. In the 1830s, there was no anti-Russian coalition in Europe; it had yet to be created. Britain could suddenly find itself in a situation of military conflict with Russia and, moreover, alone. As a result, Urquhart was recalled from Turkey, and the conflict with Russia was settled by peace talks.

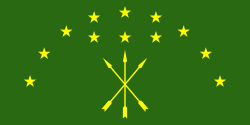

In 1835, before leaving for the East, he founded a periodical called the Portfolio, and in the first issue printed a series of Russian state papers, which made a profound impression.[1][4] Urquhart was also the self-proclaimed designer of the Circassian national flag (which was adopted as the flag of Adygea in 1992).[5]

Urquhart later publicly accused Palmerston, the head of British foreign policy, of being bribed by Russia. This view was constantly promoted in the London magazines he published. Among the regular authors of his publications was Karl Marx, who fully supported Urquhart's views on Palmerston.[6][7] Personally, Karl Marx himself, in correspondence with his friend Engels, considered Urquhart a "form of maniac" in his accusations of Palmerston and the worship of the Turks.[8]

In 1838, Urquhart published a book, Spirit of the East, where he examines Turkey and Greece, while also drawing on work previously done by Arthur Lumley Davids.[9]

Politics

[edit]From 1847 to 1852, he sat in parliament as the member for Stafford, and carried on a vigorous campaign against Lord Palmerston's foreign policy.[1][4] He was against the imposition of sanitary reform, and vehemently opposed the passage of the Public Health Act 1848.[10]

The action of the United Kingdom in the Crimean War provoked indignant protests from Urquhart, who contended that Turkey was in a position to fight her own battles without the assistance of other powers.[1] To attack the government, he organized (what became known as "Urquhartite") foreign affairs committees throughout the country.[11] In 1856 (with finance from ironmaster George Crawshay) he became the owner of the Free Press (renamed the Diplomatic Review in 1866), which numbered among its contributors the socialist Karl Marx.[12] In 1860, he published his book on Lebanon.[1][4]

Personal life

[edit]

In 1854, Urquhart married Harriet Angelina Fortescue, an Anglo-Irish aristocrat.[1] The couple had two daughters and three sons: including Francis Fortescue Urquhart.[3] Harriet was involved in Urquhart's work and wrote numerous articles for Diplomatic Review under the signature of Caritas.[3] She died in 1889.[1]

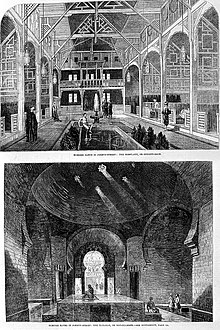

In his book The Pillars of Hercules (1850), Urquhart wrote about the hammams of Morocco and Turkey and advocated their use in the United Kingdom.[13] This attracted the attention of Irish physician Richard Barter who sought Urquhart's help in building such a bath at his hydropathic establishment in Blarney, County Cork.[14]

Although their first bath was unsuccessful, Barter persevered and, by copying the hot dry air baths of the ancient Roman thermae, built an "Improved Turkish bath" which later became known as the Victorian Turkish bath to distinguish it from the Islamic hammam.[15]

In 1857, Urquhart built the first such bath in England at Broughton Lane, Manchester, in conjunction with the local foreign affairs committee.[15]: Chapter 5 More than 30 of the first Victorian Turkish baths in England were built by members of these committees under Urquhart's direction, and the exemplar baths at 76 Jermyn Street, London, were built by the London & Provincial Turkish Bath Co Ltd, also under his direction.[15]: Chapter 8 This type of bath quickly spread round the Empire, the United States, and parts of Europe.

Starting in 1864, Urquhart lived in Clarens, Switzerland next to Lake Geneva for his health. There he devoted his energies to promoting the study of international law. He died in 1877 and is buried in Clarens.[1][4]

Select publications

[edit]- Turkey and its Resources: Its Municipal Organisation and Free Trade. London: Saunders and Otley, 1833.[16]

- England, France, Russia, and Turkey. 3rd edition. London: J. Ridgeway and Son, 1835.[17]

- The Spirit of the East. in two volumes. 2nd edition. London: Henry Colburn, Publisher, 1839.[9]

- The Crisis. France in Face of the Four Powers. Second Edition. Translated from the French. Glasgow: John Smith and Son, 1840.[18]

- "Rupture of Alliance with France." Diplomacy and Commerce vol. 5. Glasgow: John Smith & Son, 1840.[19]

- The Sulphur Monopoly. T. Brettell, 1840.[20]

- A Fragment of History of Serbia. Verlag nicht ermittelbar, 1843.[21]

- Annexation of Texas: A Case of War Between England and the United States. London: James Maynard, 1844.[22]

- England in the Western Hemisphere; the United States and Canada. London: James Maynard, 1844.[23]

- Reflections on Thoughts and Things, Moral, Religious, and Political. London: James Maynard, 1844.[24]

- The Pillars of Hercules; or, A Narrative of Travels in Spain and Morocco in 1848. in 2 volumes. London: Richard Bentley, 1850.[13]

- The Mystery of the Danube: Showing how Through Secret Diplomacy that River Has Been Closed, Exportation from Turkey Arrested, and the Re-opening of the Isthmus of Suez Prevented. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1851.[25]

- The Crown of Denmark Disposed of by a Conscientious Minister Through a Fraudulent Treaty with the Treaty of the 8th of May 1852. London: T. & W. Boone, March 1853.[26]

- Recent Events in the East: Being a Reprint of Mr. Urquhart's Contributions to the Morning Advertiser, During the Autumn of 1853. London: Trübner & Co., 1854.[27]

- The War of Ignorance and Collusion; Its Progress and Results: a Prognostication and a Testimony. London: Trübner & Co., 1854.[28]

- Familiar Words, as affecting the character of Englishmen and the Fate of England. London: Trübner & Co., 1855.[29]

- The Home Face of the “Four Points". London: Trübner & Co., 1855.[30]

- Public Opinion and Its Organs. London: Trübner & Co., 1855.[31]

- The Effect of the Misuse of Familiar Words on the Character of Men and the Fate of Nations. London: Trübner & Co., 1856.[32]

- The Question is Mr. Urquhart a Tory Or a Radical? Answered by His Constitution for the Danubian Principalities. Sheffield: Isaac Ironside, 1856.[33]

- The Queen and the Premier: A Statement of Their Struggle and Its Results. 2nd Edition. London: David Bryce, 1857.[34]

- The Sraddha: The Keystone of the Brahminical, Buddhistic, and Arian Religions, as Illustrative of the Dogma and Duty of Adoption Among the Princes and People of India. London: David Bryce, 1857.[35]

- Mr. Urquhart on the Italian War…to Which is Added a Memoir on Europe Drawn up for the Instruction of the Present Emperor of Russia. London: Robert Hardwicke, 1859.[36]

- Selections from “Progress of Russia in the West, North and South." Reprinted from Stereotype edition. 1959.[37]

- The Lebanon: (Mount Souria): A History and a Diary. 2 volumes. London: Thomas Cautley Newby, 1860.[38]

- The New Heresy: Proselytism Substituted for Righteousness, 2 letters to the Bishop of Oxford. Whitefriars: Free Press Office, September 1862.[39]

- The Right of Search: Two Speeches by David Urquhart. London: Hardwicke, 1862.[40]

- Manual of the Turkish Bath. Heat a Mode of Cure and a Source of Strength for Men and Animals. London: John Churchill and Sons, 1865.[41]

- Conscience in Respect to Public Affairs: A Correspondence. Wyman & Sons, 1867.[42]

- Russia, If Not Everywhere, Nowhere: A Correspondence. London: Diplomatic Review Office, 1867.[43]

- The Abyssinian War: The Contingency of Failure. London: Diplomatic Review Office, December 1868.[44]

- Effect on the World of the Restoration of the Canon Law: Being a Vindication of the Catholic Church Against a Priest. London: Diplomatic Review Office, 1869.[45]

- The Military Oath and Christianity. London: Diplomatic Review Office, 1869.[46]

- The Military Strength of Turkey. London: Effingham Wilson Royal Exchange, 1869.[47]

- The Four Wars of the French Revolution. London: Diplomatic Review Office, 1874.[48]

- "Naval Power Suppressed by the Maritime States: Crimean War." Reprinted from Diplomatic Review. London: Diplomatic Review Office, 1874.[49]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Lee, Sidney, ed. (1899). "Urquhart, David". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 58. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 43–45.

- ^ "Urquhart, David (1805-1877) and Urquhart, Harriet Angelina (1825-1889)". Wellcome Collection. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Papers of David Urquhart". Balliol College Archives & Manuscripts. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Urquhart, David". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 801.

- ^ Richmond, Walter (9 April 2013). "A Pawn in the Great Game". The Circassian Genocide. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press (published 2013). p. 50. ISBN 9780813560694.

[...] Urquhart claims to have met fifteen tribal leaders and nearly two hundred village chiefs, designed the Circassian flag, and helped them draft a petition to London for assistance.

- ^ Wheen, Francis (2000). Karl Marx: A Life. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-393-04923-7.

- ^ "The Story of the Life of Lord Palmerston by Karl Marx". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "Karl Marx: A Life—ch07". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ a b Urquhart, David (1839). The Spirit of the East: Illustrated in a Journal of Travels Through Roumeli During an Eventful Period. H. Colburn – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, D (1848) in Hansard, Commons Sitting, 5 May 1848, 98, p. 717

- ^ Shannon, Richard. 'David Urquhart and the Foreign Affairs Committees' In: Pressure from without in early Victorian England. Edited by Patricia Hollis. (London: Edward Arnold, 1974)

- ^ "The Free Press". Victorian Turkish Bath. 26 May 1858. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ a b Urquhart, David (1850). The Pillars Of Hercules; Or, A Narrative Of Travels In Spain And Morocco In 1848: In Two Volumes. London: Bentley – via Google Books.

- ^ Avcıoğlu, Nebahat. (2011) Turquerie and the politics of representation, 1728-1876. (Farnham: Ashgate) pp.204—205.

- ^ a b c Shifrin, Malcolm. (2015). Victorian Turkish baths (Swindon: Historic England) Chapter 4

- ^ Urquhart, David (1833). Turkey and its Resources: its Municipal Organisation and Free Trade – via Google Books.

- ^ England (1835). England, France, Russia, and Turkey. [By David Urquhart.] Third edition. J. Ridgway and Sons – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1840). The Crisis. France in Face of the Four Powers ... Second Edition. Translated from the French – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1840). Rupture of Alliance with France. J. Smith & son – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1840). The Sulphur Monopoly: By David Urquhart. T. Brettell – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1843). A Fragment of the History of Servia. Verlag nicht ermittelbar – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1844). Annexation of the Texas: A Case of War Between England and the United States. James Maynard – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1844). England in the Western Hemisphere; the United States and Canada. [From the Portfolio of March 1st 1844.]. James Maynard – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1844). Reflections on thoughts and things, moral, religious, and political. (Reprinted from the Portfolio from Aug. 1843 to 1844.) – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1851). The Mystery of the Danube: Showing how Through Secret Diplomacy that River Has Been Closed, Exportation from Turkey Arrested, and the Re-opening of the Isthmus of Suez Prevented. Bradbury & Evans – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1853). The Crown of Denmark Disposed of by a Conscientious Minister Through a Fraudulent Treaty: With the Treaty of the 8th of May 1852. T. & W. Boone – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1854). Recent Events in the East: Being a Reprint of Mr. Urquhart's Contributions to the Morning Advertiser, During the Autumn of 1853. Trübner & Company – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1854). The War of Ignorance and Collusion; Its Progress and Results: a Prognostication and a Testimony. Trübner & Company – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1855). Familiar Words, as affecting the character of Englishmen and the fate of England. (Second Series. Familiar words as affecting the conduct of England in 1855.) – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1855). The Home Face of the "Four Points.". Tucker – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1855). Public Opinion and Its Organs. Trübner & Company – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1856). The Effect of the Misuse of Familiar Words on the Character of Men and the Fate of Nations. Trübner & Company – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1856). The Question is Mr. Urquhart a Tory Or a Radical?: Answered by His Constitution for the Danubian Principalities. I. Ironside – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1857). The Queen and the Premier: A Statement of Their Struggle and Its Results. D. Bryce – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1857). The Sraddha: The Keystone of the Brahminical, Buddhistic, and Arian Religions, as Illustrative of the Dogma and Duty of Adoption Among the Princes and People of India. D. Bryce – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1859). Mr. Urquhart on the Italian War ... To which is added a memoir on Europe drawn up for the instruction of the present Emperor of Russia – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1859). How Russia tries to get into her hands the supply of corn of the whole of Europe. The English-Turkish Treaty of 1838. (Selections from "Progress of Russia in the West, North and South." By D. U. The South ... Reprinted from the stereotype edition.) – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1860). The Lebanon: (Mount Souria.): A History and a Diary. Thomas Cautley Newby. ISBN 978-0-598-00628-8 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Urquhart, David (1862). The new heresy: proselytism substituted for righteousness, 2 letters – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1862). The Right of Search: Two Speeches by David Urquhart. (January 20 and 27, 1862.) Showing: In what it Consists. How the British Empire Exists by It. That it Has Been Surrendered Up. With an Introduction on Lord Derby's Part Therein. Hardwicke – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1865). Manual of the Turkish bath. Heat a mode of cure and a source of strength for men and animals. Ed. by sir J. Fife – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1867). Conscience in Respect to Public Affairs: A Correspondence. Wyman & Sons – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1867). Russia, If Not Everywhere, Nowhere: A Correspondence. Diplomatic Review – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1868). The Abyssinian War. Diplomatic review office – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1869). Effect on the World of the Restoration of the Canon Law: Being a Vindication of the Catholic Church Against a Priest. Diplomatic Review Office – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1869). The Military Oath and Christianity: Sequel to the "Appeal of a Protestant to the Pop". Diplomatic Review Office – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1869). The Military Strength of Turkey. Wilson – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1874). The Four Wars of the French Revolution. "Diplomatic review" office – via Google Books.

- ^ Urquhart, David (1874). Naval Power Suppressed by the Maritime States: Crimean War. "Diplomatic review" office – via Google Books.

Bibliography

[edit]- Robinson, Gertrude (1920). David Urquhart: some chapters in the life of a Victorian knight-errant of justice and liberty. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. p. xii, 328.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1957). The trouble makers: dissent over foreign policy, 1792–1939. London: Hamish Hamilton. p. 207p. ISBN 978-0241906668.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Taylor, Miles. "Urquhart, David (1805–1877)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28017. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.), 2004. ISBN 978-0198614111

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to David Urquhart at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to David Urquhart at Wikimedia Commons

KSF

KSF