Dialectic of Enlightenment

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

| |

| Authors | Max Horkheimer Theodor W. Adorno |

|---|---|

| Original title | Dialektik der Aufklärung |

| Translator | John Cumming (1972) |

| Language | German |

| Subjects | Philosophy, social criticism |

Publication date | 1947 |

| Publication place | Germany |

Published in English | 1972 (New York: Herder and Herder) |

| Media type | Print (pbk) |

| Pages | 304 |

| ISBN | 0-8047-3633-2 |

| OCLC | 48851495 |

| 193 21 | |

| LC Class | B3279.H8473 P513 2002 |

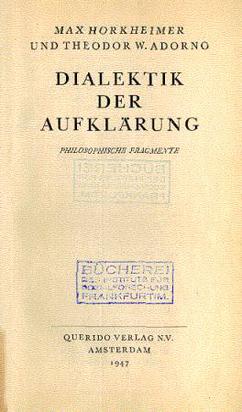

Dialectic of Enlightenment (German: Dialektik der Aufklärung) is a work of philosophy and social criticism written by Frankfurt School philosophers Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno.[1] The text, published in 1947, is a revised version of what the authors originally had circulated among friends and colleagues in 1944 under the title of Philosophical Fragments (German: Philosophische Fragmente).[2]

One of the core texts of critical theory, Dialectic of Enlightenment explores the socio-psychological status quo that had been responsible for what the Frankfurt School considered the failure of the Enlightenment. They argue that its failure culminated in the rise of Fascism, Stalinism, the culture industry and mass consumer capitalism. Rather than liberating humanity as the Enlightenment had promised, they argue it had resulted in the opposite: in totalitarianism, and new forms of barbarism and social domination.[3]

Together with Adorno's The Authoritarian Personality (1950) and fellow Frankfurt School member Herbert Marcuse's One-Dimensional Man (1964), it has had a major effect on 20th-century philosophy, sociology, culture, and politics, especially inspiring the New Left of the 1960s and 1970s.[4]

Historical context

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Frankfurt School |

|---|

|

In the 1969 preface to the 2002 publication, Horkheimer and Adorno wrote that the original was written, "when the end of the National Socialist terror was in sight."[5]: xi One of the distinguishing characteristics of the new critical theory, as Adorno and Horkheimer set out to elaborate it in Dialectic of Enlightenment, is a certain ambivalence concerning the ultimate source or foundation of social domination.[5]: 229

Such would give rise to the "pessimism" of the new critical theory over the possibility of human emancipation and freedom.[5]: 242 Furthermore, this ambivalence was rooted in the historical circumstances in which Dialectic of Enlightenment was originally produced: the authors saw National Socialism, Stalinism, state capitalism, and culture industry as entirely new forms of social domination that could not be adequately explained within the terms of traditional theory.[6][7]

For Adorno and Horkheimer (relying on economist Friedrich Pollock's thesis[8] on National Socialism),[9] state intervention in the economy and the increasing concentration of capital had concealed the contradiction within capitalism between the coercive relations of production and the level of productive forces—a tension that traditional theory expected to be resolved through a proletarian revolution. The liberal market economy, once associated with individual autonomy and competition among private entrepreneurs, had evolved into a system of centralized planning.[5]: 38

[G]one are the objective laws of the market which ruled in the actions of the entrepreneurs and tended toward catastrophe. Instead the conscious decision of the managing directors executes as results (which are more obligatory than the blindest price-mechanisms) the old law of value and hence the destiny of capitalism.

— Dialectic of Enlightenment, p. 38

Because of this, contrary to Marx's famous prediction in his preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, this shift did not lead to "an era of social revolution," but rather to fascism and totalitarianism. As such, traditional theory was left, in Jürgen Habermas' words, without "anything in reserve to which it might appeal; and when the forces of production enter into a baneful symbiosis with the relations of production that they were supposed to blow wide open, there is no longer any dynamism upon which critique could base its hope."[10]: 118 For Adorno and Horkheimer, this posed the problem of how to account for the apparent persistence of domination in the absence of the very contradiction that, according to traditional critical theory, was the source of domination itself.[4]

Topics and themes

[edit]The problems posed by the rise of fascism with the demise of the liberal state and the market (together with the failure of a social revolution to materialize in its wake) constitute the theoretical and historical perspective that frames the overall argument of the book—the two theses that "Myth is already enlightenment, and enlightenment reverts to mythology."[5]: xviii

The history of human societies, as well as that of the formation of individual ego or self, is re-evaluated from the standpoint of what Horkheimer and Adorno perceived at the time as the ultimate outcome of this history: the collapse or regression of reason, with the rise of National Socialism, into something resembling the very forms of superstition and myth out of which reason had supposedly emerged as a result of historical progress or development.

Horkheimer and Adorno believe that in the process of Enlightenment, modern philosophy had become uncritical and an instrument of technocracy. They characterize a key part of this process as the historical transition of rationality into positivism, referring to both the logical positivism of the Vienna Circle and broader trends that they saw in continuity with this movement.[11] Horkheimer and Adorno's critique of positivism has been criticized as too broad; they are particularly critiqued for interpreting Ludwig Wittgenstein as a positivist—at the time only his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus had been published, not his later works—and for failing to examine critiques of positivism from within analytic philosophy.[12] However, Adorno's later contributions to The Positivist Dispute in German Sociology present a more differentiated critique of positivism, including attention to internal debates and methodological tensions within the tradition.[13]

To characterize this history, Horkheimer and Adorno draw on a wide variety of material, including the philosophical anthropology contained in Marx's early writings, centered on the notion of "labor;" Nietzsche's genealogy of morality, and the emergence of conscience through the renunciation of the will to power; Freud's account in Totem and Taboo of the emergence of civilization and law in murder of the primordial father;[14] and ethnological research on magic and rituals in primitive societies;[15] as well as myth criticism, philology, and literary analysis.[16]

Adorno and Horkheimer argue that antisemitism is a deeply rooted, irrational phenomenon that stems from the failure of the Enlightenment project and the inherent contradictions of bourgeois society. They argue that Jews serve as a universal scapegoat onto which individuals and societies project their deepest fears, anxieties, and neuroses. According to their analysis, the complex and often contradictory nature of modern life generates a sense of alienation, powerlessness, and psychological distress. Unable to confront these feelings directly, people seek to externalize them by identifying a tangible "other" to blame for their problems. The Jews, with their historically marginalized status and perceived association with the disruptive forces of modernity, become an ideal target for this projection.[1]

Adorno and Horkheimer suggest that antisemitic stereotypes, such as the Jews' alleged greed, cunning, and rootlessness, are not based on any objective reality but rather reflect the unconscious fears and desires of the antisemites themselves. By attributing their own negative impulses to the Jews, they are able to maintain a sense of psychological coherence and moral purity. This irrational, projective hatred is further reinforced by economic resentment and nationalistic ideology, which provide a broader social framework for antisemitism. Ultimately, Adorno and Horkheimer see the persecution of the Jews as a symptom of the unresolved contradictions and pathologies of modern society, which can only be addressed through a radical critique of the Enlightenment project and the social conditions that sustain it.[1]

The authors coined the term culture industry, arguing that in a capitalist society, mass culture is akin to a factory producing standardized cultural goods—films, radio programmes, magazines, etc.[17] These homogenized cultural products are used to manipulate mass society into docility and passivity.[18] The introduction of the radio, a mass medium, no longer permits its listener any mechanism of reply, as was the case with the telephone. Instead, listeners are not subjects anymore but passive receptacles exposed "in authoritarian fashion to the same programs put out by different stations."[19]

By associating the Enlightenment and Totalitarianism with Marquis de Sade's works—especially Juliette, in excursus II—the text also contributes to the pathologization of sadomasochist desires, as discussed by historian of sexuality Alison Moore.[20]

Editions

[edit]The book was first published as Philosophische Fragmente in New York in 1944, by the Institute for Social Research, which had relocated from Frankfurt am Main ten years earlier. A revised version was published as Dialektik der Aufklärung in Amsterdam by Querido in 1947. It was reissued in Frankfurt by S. Fischer in 1969, with a new preface by the authors.

There have been two English translations: the first by John Cumming (New York: Herder and Herder, 1972; reissues by Verso from 1979 reverse the order of the authors' names), and another, based on the definitive text from Horkheimer's collected works, by Edmund Jephcott (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002).

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Max Horkheimer; Theodor W. Adorno (1972) [1947]. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Translated by John Cumming. New York: Herder and Herder. ISBN 0-8047-3633-2. OCLC 48851495.

- ^ Schmidt, James (1998). "'Language, Mythology, and Enlightenment: Historical Notes on Horkheimer and Adorno's Dialectic of Enlightenment.'". Social Research. 65 (4): 807-38 (p.809).

- ^ Cikaj, Klejton (2023-05-04). "Dialectic of Enlightenment: Adorno & Horkheimer's Work in 6 Parts". The Collector. Retrieved 2024-03-22.

- ^ a b Held, D. (1980). Introduction to Critical Theory: Horkheimer to Habermas. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- ^ a b c d e Horkheimer, Max; Adorno, Theodor W. (2002) [1947]. Schmid Noerr, Gunzelin (ed.). Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments (PDF). Translated by Jephcott, Edmund. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3632-4.

- ^ Habermas, Jürgen. [1985] 1987. The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity: Twelve Lectures, translated by F. Lawrence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 116: "Critical Theory was initially developed in Horkheimer's circle to think through political disappointments at the absence of revolution in the West, the development of Stalinism in Soviet Russia, and the victory of fascism in Germany. It was supposed to explain mistaken Marxist prognoses, but without breaking Marxist intentions."

- ^ Dubiel, Helmut (1985) [1978]. Theory and Politics: Studies in the Development of Critical Theory. Translated by Gregg, Benjamin Greenwood. Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press. p. 207. ISBN 0-262-04080-8.

- ^ Pollock, Friedrich. 1941. "Is National Socialism a New Order?" Studies in Philosophy and Social Science 9 (2):440–45. p. 453.

- ^ van Reijen, Willem, and Jan Bransen. "The Disappearance of Class History in the Dialectic of Enlightenment." In Dialectic of Enlightenment. p. 248.

- ^ Habermas, Jürgen. 1982. "The Entwinement of Myth and Enlightenment: Re-Reading 'Dialectic of Enlightenment'." New German Critique 26(4):13-30. doi:10.2307/488023. JSTOR 488023.

- ^ Josephson-Storm, Jason (2017). The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 244–5. ISBN 978-0-226-40336-6.

- ^ Josephson-Storm (2017, pp. 242, 243–4)

- ^ Adorno, Theodor W. (1976). "Introduction". The Positivist Dispute in German Sociology. London: Heinemann. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-0435826550.

- ^ Dialectic of Enlightenment, 7, 159, 162.

- ^ Dialectic of Enlightenment, 10, 256.

- ^ Moore, Alison (September 2010). "Sadean Nature and Reasoned Morality in Adorno/Horkheimer's 'Dialectic of Enlightenment'". Psychology and Sexuality. 1 (3): 249–260. doi:10.1080/19419899.2010.494901. S2CID 143713118.

- ^ pp. 94–5 quotation:

Culture today is infecting everything with sameness. Film, radio, and magazines form a system. Each branch of culture is unanimous within itself and all are unanimous together. Even the aesthetic manifestations of political opposites proclaim the same inflexible rhythm...All mass culture under monopoly is identical... Films and radio no longer need to present themselves as art. The truth that they are nothing but business is used as an ideology to legitimize the trash they intentionally produce.

- ^ pp. 94–5 quotation:

...The standardized forms, it is claimed, were originally derived from the needs of the consumers: that is why they are accepted with so little resistance. In reality, a cycle of manipulation and retroactive need is unifying the system ever more tightly.

- ^ pp. 95–6 quotation:

The step from telephone to radio has clearly distinguished the roles. The former liberally permitted the participant to play the role of subject. The latter democratically makes everyone equally into listeners, in order to expose them in authoritarian fashion to the same programs put out by different stations. No mechanism of reply has been developed...

- ^ Moore, Alison M. 2015. Sexual Myths of Modernity: Sadism, Masochism and Historical Teleology. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-3077-3.

External links

[edit]- "The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception." Excerpt of "The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception" from The Dialectic of Enlightenment, transcribed by A. Blunden [1998] 2005.

- "Dialectic of Enlightenment," in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

KSF

KSF