Dictator

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a polity.[1] The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in times of emergency.[1] Like the terms "tyrant" and "autocrat", dictator came to be used almost exclusively as a non-titular term for oppressive rule. In modern usage, the term dictator is generally used to describe a leader who holds or abuses an extraordinary amount of personal power.

Dictatorships are often characterised by some of the following: suspension of elections and civil liberties; proclamation of a state of emergency; rule by decree; repression of political opponents; not abiding by the procedures of the rule of law; and the existence of a cult of personality centered on the leader. Dictatorships are often one-party or dominant-party states.[2][3] A wide variety of leaders coming to power in different kinds of regimes, such as one-party or dominant-party states and civilian governments under a personal rule, have been described as dictators.

Etymology

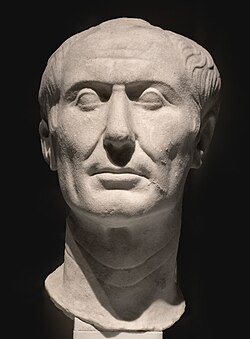

[edit]The word dictator comes from the Latin word dictātor, agent noun from dictare (say repeatedly, assert, order).[4][5] A dictator was a Roman magistrate given sole power for a limited duration. Originally an emergency legal appointment in the Roman Republic and the Etruscan culture, the term dictator did not have the negative meaning it has now.[6] It started to get its modern negative meaning with Cornelius Sulla's ascension to the dictatorship following Sulla's civil war, making himself the first Dictator in Rome in more than a century (during which the office was ostensibly abolished) as well as de facto eliminating the time limit and need of senatorial acclamation.[7]

He avoided a major constitutional crisis by resigning the office after about one year, dying a few years later. Julius Caesar followed Sulla's example in 49 BC and in February 44 BC was proclaimed Dictator perpetuo, "Dictator in perpetuity", officially doing away with any limitations on his power, which he kept until his assassination the following month. Following Caesar's assassination, his heir Augustus was offered the title of dictator, but he declined it. Later successors also declined the title of dictator, and usage of the title soon diminished among Roman rulers.[8]

Modern era

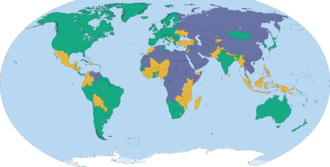

[edit]Free (86) Partly Free (59) Not Free (50)

As late as the second half of the 19th century, the term dictator had occasional positive implications. For example, during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, the national leader Lajos Kossuth was often referred to as dictator, without any negative connotations, by his supporters and detractors alike, although his official title was that of regent-president.[11] When creating a provisional executive in Sicily during the Expedition of the Thousand in 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi officially assumed the title of "dictator" (see Dictatorship of Garibaldi). Shortly afterwards, during the 1863 January uprising in Poland, "Dictator" was also the official title of four leaders, the first being Ludwik Mierosławski.

Past that time, however, the term dictator assumed an invariably negative connotation. In popular usage, a dictatorship is often associated with brutality and oppression. As a result, it is often also used as a term of abuse against political opponents. Many dictators create a cult of personality around themselves and they have also come to grant themselves increasingly grandiloquent titles and honours.[14] For instance, Idi Amin Dada, who had been a British army lieutenant prior to Uganda's independence from Britain in October 1962, subsequently styled himself "His Excellency, President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji Doctor[A] Idi Amin Dada, VC,[B] DSO, MC, Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular".[15] In the movie The Great Dictator (1940), Charlie Chaplin satirized not only Adolf Hitler but the institution of dictatorship itself.

Characteristics

[edit]Benevolent dictatorship

[edit]A benevolent dictatorship refers to a government in which an authoritarian leader exercises absolute political power over the state but is perceived to do so with regard for the benefit of the population as a whole, standing in contrast to the decidedly malevolent stereotype of a dictator. A benevolent dictator may allow for some civil liberties or democratic decision-making to exist, such as through public referendums or elected representatives with limited power, and often makes preparations for a transition to genuine democracy during or after their term. The label has been applied to leaders such as Mustafa Kemal Atatürk of Turkey (1923–38),[16] Josip Broz Tito of SFR Yugoslavia (1953–80),[17] and Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore (1959–90).[18]

Military roles

[edit]The association between a dictator and the military is a common one. Many dictators take great pains to emphasize their connections with the military and they often wear military uniforms. In some cases, this is perfectly legitimate; for instance, Francisco Franco was a general in the Spanish Army before he became Chief of State of Spain,[19] and Manuel Noriega was officially commander of the Panamanian Defense Forces.[20]

Crowd manipulation

[edit]Some dictators have been masters of crowd manipulation, such as Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler. Others were more prosaic speakers, such as Joseph Stalin and Francisco Franco. Typically, the dictator's people seize control of all media, censor or destroy the opposition, and give strong doses of propaganda daily, often built around a cult of personality.[21]

Mussolini and Hitler used similar titles referring to them as "the Leader". Mussolini used "Il Duce" and Hitler was generally referred to as "der Führer", both meaning 'Leader' in Italian and German respectively. Franco used a similar title, "El Caudillo" ("the Head", 'the chieftain').[22] In the case of Franco, the title "Caudillo" did have a longer history for political-military figures in both Latin America and Spain. Franco also used the phrase "By the Grace of God" on coinage or other material displaying him as Caudillo.[23]

Human rights abuses, war crimes and genocides

[edit]

Over time, dictators have been known to use tactics that violate human rights. For example, under the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, government policy was enforced by secret police and the Gulag system of prison labour camps. Most Gulag inmates were not political prisoners, although significant numbers of political prisoners could be found in the camps at any one time. Data collected from Soviet archives gives the death toll from Gulags as 1,053,829.[27] The International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Sudan's military dictator Omar al-Bashir over alleged war crimes in Darfur.

Similar crimes were committed during Chairman Mao Zedong's rule over the People's Republic of China during China's Cultural Revolution, where Mao set out to purge dissidents, primarily through the use of youth groups strongly committed to his cult of personality,[28] and during Augusto Pinochet's junta in Chile.[29] Some dictators have been associated with genocide on certain races or groups; the most notable and wide-reaching example is the Holocaust, Adolf Hitler's genocide of eleven million people, of whom six million were Jews.[30] Later on in Democratic Kampuchea, General Secretary Pol Pot and his policies killed an estimated 1.7 million people (out of a population of 7 million) during his four-year dictatorship.[31] As a result, Pol Pot is sometimes described as "the Hitler of Cambodia" and "a genocidal tyrant".[32]

Modern usage in formal titles

[edit]

Because of its negative and pejorative connotations, modern authoritarian leaders very rarely (if ever) use the term dictator in their formal titles, instead they most often simply have title of president. In the 19th century, however, its official usage was more common:[35]

- The Dictatorial Government of Sicily (27 May – 4 November 1860) was a provisional executive government appointed by Giuseppe Garibaldi to rule Sicily during the Expedition of the Thousand. The government ended when Sicily's annexation into the Kingdom of Italy was ratified by plebiscite.[36]

- Marian Langiewicz of Poland proclaimed himself Dictator and attempted (unsuccessfully) to form a Polish government in March 1863.[37]

- Romuald Traugutt was Dictator of Poland from 17 October 1863 to 10 April 1864.[38]

- The Dictatorial Government of the Philippines (24 May – 23 June 1898) was an insurgent government in the Philippines which was headed by Emilio Aguinaldo, who formally held the title of Dictator.[39] The dictatorial government was superseded by the revolutionary government with Aguinaldo as president.

Criticism

[edit]The usage of the term dictator in western media has been criticized by the left-leaning organization Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting as "Code for Government We Don't Like". According to them, leaders that would generally be considered authoritarian but are allied with the United States such as Paul Biya or Nursultan Nazarbayev are rarely referred to as "dictators", while leaders of countries opposed to U.S. policy such as Nicolás Maduro or Bashar al-Assad have the term applied to them much more liberally.[40]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Informational notes

[edit]- A ^ He conferred a doctorate of law on himself from Makerere University.[41]

- B ^ The Victorious Cross (VC) was a medal made to emulate the British Victoria Cross.[42]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "Lessons in On-Line Reference PublishingMerriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary. Merriam-WebsterMerriam-Webster's Collegiate Thesaurus. Merriam-WebsterMerriam-Webster's Collegiate Encyclopedia. Merriam-Webster". The Library Quarterly. 71 (3): 392–399. July 2001. doi:10.1086/603287. ISSN 0024-2519. S2CID 148183387.

- ^ Papaioannou, Kostadis; vanZanden, Jan Luiten (2015). "The Dictator Effect: How long years in office affect economic development". Journal of Institutional Economics. 11 (1): 111–139. doi:10.1017/S1744137414000356. hdl:1874/329292. S2CID 154309029.

- ^ Olson, Mancur (1993). "Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development". American Political Science Review. 87 (3): 567–576. doi:10.2307/2938736. JSTOR 2938736. S2CID 145312307.

- ^ "Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, dicto". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2024-01-17.

- ^ "Oxford English Dictionary".

- ^ Le Glay, Marcel. (2009). A history of Rome. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8327-7. OCLC 760889060. Archived from the original on 2020-07-25. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- ^ Wilson, Mark B. (2021). Dictator: the evolution of the Roman dictatorship. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 325. ISBN 9780472132669.

- ^ Wilson, Mark B. (2021). Dictator: the evolution of the Roman dictatorship. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 330. ISBN 9780472132669.

- ^ Freedom in The World 2017 – Populists and Autocrats: The Dual Threat to Global Democracy Archived 2017-07-27 at the Wayback Machine by Freedom House, January 31, 2017

- ^ "Democracy Index 2017 – Economist Intelligence Unit" (PDF). EIU.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ Macartney, Carlile Aylmer (September 15, 2020). Lajos Kossuth. Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ "The brutal central African dictator whose playboy son faces French corruption trial". The Independent. 12 September 2016.

- ^ "The Five Worst Leaders In Africa". Forbes. 9 February 2012.

- ^ Treisman, Daniel; Guriev, Sergei (4 April 2023). Spin Dictators: The Changing Face of Tyranny in the 21st Century. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-22447-3.

- ^ Keatley, Patrick (18 August 2003). "Obituary: Idi Amin". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2013-12-05. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ^ "Atatürk, Ghazi Mustapha Kemal (1881–1938) | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ Shapiro, Susan; Shapiro, Ronald (2004). The Curtain Rises: Oral Histories of the Fall of Communism in Eastern Europe. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1672-1. Archived from the original on 2021-05-12. Retrieved 2019-01-19.

"...All Yugoslavs had educational opportunities, jobs, food, and housing regardless of nationality. Tito, seen by most as a benevolent dictator, brought peaceful co-existence to the Balkan region, a region historically synonymous with factionalism." - ^ Miller, Matt (2012-05-02). "What Singapore can teach us". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2015-11-25.

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (1977). The Spanish Civil War. Harper & Row. pp. 421–424. ISBN 978-0-06-014278-0.

- ^ Dinges, John (26 September 2023). Our Man in Panama: The Shrewd Rise and Brutal Fall of Manuel Noriega. Open Road Media. ISBN 978-1-5040-8719-3.

- ^ Morstein, Marx Fritz; et al. (March 2007). Propaganda and Dictatorship. Princeton UP. ISBN 978-1-4067-4724-9.

- ^ Hamil, Hugh M., ed. (1992). "Introduction". Caudillos: Dictators in Spanish America. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-8061-2428-5.

- ^ Moradiellos, Enrique (18 December 2017). Franco: Anatomy of a Dictator. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-78673-300-9.

- ^ S.B. (21 August 2013). "Syria's war: If this isn't a red line, what is?". The Economist. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ "Syria gas attack: death toll at 1,400 worst since Halabja". The Week. 22 August 2013. Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ D. Ward, Kenneth (September 2021). "Syria, Russia, and the Global Chemical Weapons Crisis". Arms Control Association. Archived from the original on 8 July 2023.

- ^ "Gulag Prisoner Population Statistics from 1934 to 1953." Wasatch.edu. Wasatch, n.d. Web. 16 July 2016: "According to a 1993 study of Soviet archival data, a total of 1,053,829 people died in the Gulag from 1934 to 1953. However, taking into account that it was common practice to release prisoners who were either suffering from incurable diseases or on the point of death, the actual Gulag death toll was somewhat higher, amounting to 1,258,537 in 1934–53, or 1.6 million deaths during the whole period from 1929 to 1953.."

- ^ "Remembering the dark days of China's Cultural Revolution". South China Morning Post. 18 August 2012. Archived from the original on 2018-06-09. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ Pamela Constable and Arturo Valenzuela, A Nation of Enemies: Chile Under Pinochet, New York: W.W Norton & Company, 1993., p. 91

- ^ "The Holocaust". The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. Archived from the original on 2021-07-15. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ ""Top 15 Toppled Dictators". Time. 20 October 2011. Archived from the original on 2013-08-24. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ William Branigin, Architect of Genocide Was Unrepentant to the End Archived 2013-05-09 at the Wayback Machine The Washington Post, April 17, 1998

- ^ "Scholar and Patriot". Manchester University Press. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 5 April 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Giuseppe Garibaldi (Italian revolutionary)". Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Moisés Prieto, ed. Dictatorship in the Nineteenth Century: Conceptualisations, Experiences, Transfers (Routledge, 2021).

- ^ Cesare Vetter, "Garibaldi and the dictatorship: Features and cultural sources." in Dictatorship in the Nineteenth Century (Routledge, 2021) pp. 113–132.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Stefan Kieniewicz, "Polish Society and the Insurrection of 1863." Past & Present 37 (1967): 130–148.

- ^ "The First Philippine Republic". National Historical Commission. 7 September 2012. Archived from the original on 27 January 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

On June 20, Aguinaldo issued a decree organizing the judiciary, and on June 23, again upon Mabini's advice, major changes were promulgated and implemented: change of government from Dictatorial to Revolutionary; change of the Executive title from Dictator to President

- ^ "Dictator: Media Code for 'Government We Don't Like'". FAIR. 2019-04-11. Archived from the original on 2021-04-16. Retrieved 2021-04-07.

- ^ "Idi Amin: a byword for brutality". News24. 2003-07-21. Archived from the original on 2008-06-05. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Lloyd, Lorna (2007). Diplomacy with a Difference: The Commonwealth Office of High Commissioner, 1880–2006. University of Michigan: Martinus Nijhoff. p. 239. ISBN 978-90-04-15497-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Online books on dictatorship at the Internet Archive (search of titles containing "dictator").

- Acemoglu, Daron; James A. Robinson (2009). Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (Reprint ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521855266. OCLC 698971569. .

- Applebaum, Anne (2024). Autocracy, Inc.: The Dictators Who Want to Run the World. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 9780385549936. OCLC 1419440360.

- Armillas-Tiseyra, Magalí (2019). The Dictator Novel: Writers and Politics in the Global South. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 9780810140417. OCLC 1050363415.

- Baehr, Peter; Melvin Richter (2004). Dictatorship in History and Theory. Publications of the German Historical Institute. Washington, D.C.; Cambridge: German Historical Institute; Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521825634. OCLC 52134632. Scholarly focus on 19th century Europe.

- Ben-Ghiat, Ruth (2020). Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393868418. OCLC 1233267123.

- Brooker, Paul (1997). Defiant Dictatorships: Communist and Middle-Eastern Dictatorships in a Democratic Age. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9780814713112. OCLC 36817139.

- Costa Pinto, António (2019). Latin American Dictatorships in the Era of Fascism: The Corporatist Wave. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780367243852. OCLC 1099538601.

- Crowson, N. J. (1997). Facing Fascism: The Conservative Party and the European Dictators 1935–1940. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415153157. OCLC 36662892. How the Conservative government in Britain dealt with them.

- Dávila, Jerry (2013). Dictatorship in South America. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405190558. OCLC 820108972.

- Galván, Javier A. (2013). Latin American Dictators of the 20th Century: The Lives and Regimes of 15 Rulers. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786466917. OCLC 794708240.

- Hamill, Hugh M. (1995). Caudillos: Dictators in Spanish America (New ed.). Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806124285. OCLC 1179406479.

- Harford Vargas, Jennifer (2018). Forms of Dictatorship: Power, Narrative, and Authoritarianism in the Latina/o Novel. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190642853. OCLC 983824496.

- Im, Chi-hyŏn; Karen Petrone, eds. (2010). Gender Politics and Mass Dictatorship: Global Perspectives. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230242043. OCLC 700131132. * Kim, Michael; Michael Schoenhals; Yong-Woo Kim, eds. (2013). Mass Dictatorship and Modernity. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137304322. OCLC 810117713.

- Lüdtke, Alf, ed. (2015). Everyday Life in Mass Dictatorship: Collusion and Evasion. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137442765. OCLC 920469575.

- Mainwaring, Scott; Aníbal Pérez-Liñán, eds. (2014). Democracies and Dictatorships in Latin America: Emergence, Survival, and Fall. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521190015. OCLC 851642671.

- Moore, Barrington Jr. (1966). Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807050736. OCLC 28065698.

- Peake, Lesley (2021). Guide to History's Worst Dictators: From Emperor Nero to Vlad the Impaler and More. N/a: Self published. ISBN 9798737828066. OCLC 875273089.

- Rank, Michael (2013). History's Worst Dictators: A Short Guide to the Most Brutal Rulers, from Emperor Nero to Ivan the Terrible. Moreno Valley, Calif.: Solicitor Publishing. OCLC 875273089. Popular; eBook.

- Spencer, Robert (2021). Dictators Dictatorship and the African Novel: Fictions of the State Under Neoliberalism. Chaim, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9783030665555. OCLC 1242746124.

- Weyland, Kurt Gerhard (2019). Revolution and Reaction: The Diffusion of Authoritarianism in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108483551. OCLC 1076804405.

External links

[edit]- Dictatorship- Encyclopedia Britannica

KSF

KSF