Divine Comedy Illustrated by Botticelli

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

| Divine Comedy Illustrated by Botticelli | |

|---|---|

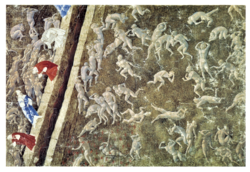

The Map of Hell painting by Botticelli is one of the extant ninety-two drawings that were originally included in the illustrated manuscript of Dante's Divine Comedy | |

| Artist | Sandro Botticelli |

| Year | mid-1480s-mid-1490s[1] |

The Divine Comedy Illustrated by Botticelli is a manuscript of the Divine Comedy by Dante, illustrated by 92 full-page pictures by Sandro Botticelli that are considered masterpieces and amongst the best works of the Renaissance painter. The images are mostly not taken beyond silverpoint drawings, many worked over in ink, but four pages are fully coloured.[1][3] The manuscript eventually disappeared and most of it was rediscovered in the late nineteenth century, having been detected in the collection of the Duke of Hamilton by Gustav Friedrich Waagen, with a few other pages being found in the Vatican Library.[4] Botticelli had earlier produced drawings, now lost, to be turned into engravings for a printed edition, although only the first nineteen of the hundred cantos were illustrated.

In 1882 the main part of the manuscript was added to the collection of the Kupferstichkabinett Berlin (Museum of Prints and Drawings) when the director Friedrich Lippmann bought 85 of Botticelli's drawings.[4] Lippmann had moved swiftly and quietly, and when the sale was announced there was a considerable outcry in the British press and Parliament.[5] Soon after that, it was revealed that another eight drawings from the same manuscript were in the Vatican Library. The bound drawings had been in the collection of Queen Christina of Sweden and after her death in Rome in 1689, had been bought by Pope Alexander VIII for the Vatican collection. The time of separation of these drawings is unknown. The Map of Hell is in the Vatican collection.[4]

The exact arrangement of text and illustrations is not known, but a vertical arrangement — placing the illustration page on top of the text page — is agreed on by scholars as a more efficient way of combining the text-illustration pairs. A volume designed to open vertically would be approximately 47 cm wide by 64 cm high, and would incorporate both the text and the illustration for each canto on a single page.

The Berlin drawings and those in the Vatican collection were assembled together, for the first time in centuries, in an exhibition showing all 92 of them in Berlin, Rome, and London's Royal Academy, in 2000–01.[6]

The 1481 printed edition

[edit]

The drawings in the manuscript were not the first to be created by Botticelli for the Divine Comedy. He also illustrated another Commedia, this time a printed edition with engravings as illustrations, that was published by Nicholo di Lorenzo della Magna in Florence in 1481, and is mentioned by Vasari. Scholars agree that the engravings by Baccio Baldini follow drawn designs by Botticelli, though unfortunately Baldini was unable to render Botticelli's style very effectively.[7][8]

Botticelli's attempt to design the illustrations for a printed book was unprecedented for a leading painter, and though it seems to have been something of a flop, this was a role for artists that had an important future.[9] Vasari wrote disapprovingly of the edition: "being of a sophistical turn of mind, he there wrote a commentary on a portion of Dante and illustrated the Inferno which he printed, spending much time over it, and this abstention from work led to serious disorders in his living."[10] Vasari, who lived when printmaking had become far more important than in Botticelli's day, never takes it seriously, perhaps because his own paintings did not sell well in reproduction.

The Divine Comedy consists of 100 cantos, and the printed text left space for one engraving for each canto. However, only 19 illustrations were engraved, and most copies of the book have only the first two or three. The first two, and sometimes three, are usually printed on the book page, while the later ones are printed on separate sheets that are pasted into place. This suggests that the production of the engravings lagged behind the printing, and the later illustrations were pasted into the stock of printed and bound books, and perhaps sold to those who had already bought the book. Unfortunately Baldini was neither very experienced nor talented as an engraver, and was unable to express the delicacy of Botticelli's style in his plates.[11] The project may have been disrupted by Botticelli's summons to Rome to take part in the project to fresco the Sistine Chapel. He was perhaps away from July 1481 to at the latest May 1482.[12]

Conception and progress of the manuscript

[edit]

It is often thought that Botticelli's drawings were commissioned by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici, an important patron of the artist. The early 16th-century writer known as the Anonimo Magliabecchiano says that Botticelli painted a Dante on parchment for Lorenzo, but makes it sound as if this was a completed work. Alternatively the drawings we have may have been a different set for Botticelli's own use and pleasure, which is the conclusion of Ronald Lightbown.[14]

Although the printed and illustrated book was rapidly replacing the traditional and very expensive illuminated manuscript in the last decades of the 15th century, the grandest bibliophiles were still commissioning manuscripts,[15] and continued to do so well into the next century, from artists such as Giulio Clovio (1498–1578), perhaps the last major artist to be mainly a manuscript illuminator.

The drawings illustrate a manuscript of Dante's Divine Comedy. The entire thematic sequence of each canto was supposed to be illustrated by its own full-page drawing by Botticelli, an unprecedentedly ambitious conception. Normally, by the 15th century, a single incident was shown in each framed illustration in illustrated Dantes, as for other narrative works. Botticelli was combining this tradition with another, continuous narrative, where recurrent incidents were shown, usually unframed and in the margin below the text. Thus the principal figures of Dante, Virgil and Beatrice often appear several times in an image.[16]

There are two additional drawings, a map of Hell preceding Inferno, and a double-page drawing of Lucifer that depicts Dante's and Virgil's descent to Hell.[1] The text is written on the reverse of the drawings, so that it was on the same page as the next drawing. As was usual, the text was completed before the illustrations were begun, omitting the major capital letters which were to be illuminated.[3]

The exact date of creation of the drawings is unknown but it is agreed that they were produced over a period of several years, and a stylistic development has been detected.[17] Estimates vary between a start around the mid-1480s with the last approximately a decade later,[1] and a period extending between about 1480 and 1505 (by which time Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco was dead).[18] Botticelli never completed the task. Many of the images are not fully drawn and illumination is completed for only four of them. However, the drawings are of such artistry and beauty, that they have been described as "central to Botticelli's artistic achievement" and no less important than the Primavera.[1] They represent by far the bulk of surviving drawings by Botticelli. Of the small number of other sheets surviving, none relate directly to surviving paintings.[19]

Botticelli is thought to have started the drawings at least roughly following the text sequence. The drawing for Canto I of Inferno has the figures at a larger scale than that used in later cantos, up to the end of the Purgatorio. The earlier drawings for the Inferno are generally the most completed, and the most detailed,[20] but cantos II to VII, XI and XIV are missing, though probably made by Botticelli. We have the text pages for the last cantos, Paradiso, XXXI to XXXIII, but the drawings were never begun.[21] The differing degrees of completion, and the canto numbers and first lines of the matching text inscribed on some sequences of pages but not others, all complicate understanding Botticelli's progress, and have been extensively debated.[22]

Technique

[edit]

Each page was first drawn with a metal stylus, leaving lines that are now very faint. There are numerous changes evident, which are easy to make in this technique. The next stage was to go over these lines with a pen and black or brown ink. Most of the pages were not taken beyond these stages, which are often found together on a page, with only some areas inked over. Other pages have not yet been inked at all. Only four pages fully received the final stage of colouring in tempera, though others are part-coloured, usually just the main figures. It has been argued that Botticelli, or his patron, came to prefer the uncoloured drawings, and deliberately left the rest, but this is not accepted by most scholars.[23]

Structure and innovations

[edit]

Botticelli's manuscripts incorporate several innovations in the way text and images are presented in the volume. In other similar illustrated manuscripts of Dante's Inferno, multiple illustrations were used to depict the events described in a canto. In addition, most of the space in a page was given to the illustration and associated commentary while the text portion was smaller in comparison. Therefore, a single canto spread over multiple pages. Botticelli's text and illustration arrangement innovates by presenting the text on a single page in four vertical columns.[25]

In addition, unlike similar works, Botticelli's manuscript uses but a single illustration per canto, which occupied a whole page, presenting a unified depiction of the sequence of events of a canto in a vertical format. This way, the readers know that when they advance to a new page, they enter the thematic sequence of a new canto.[25] The text of each canto, from left to right, matches, to a high degree,[25] the pictorial representation as the reader views the illustration from the upper left corner and then proceeds downwards. This reflects the vertical structure of the descent of the two poets through the nine circles of Hell. The additional two illustrations of the Map of Hell and Lucifer lie outside this canto-text structure, thus providing an element of continuity which unifies the work.[26] Lucifer's second drawing by Botticelli from Inferno XXXIV spans across two pages, and lies outside the text-illustration structure, unifying the narrative of the series. It also illustrates the full story of Inferno canto XXXIV and shows Lucifer's geographical position in Hell.[13]

Botticelli renders vertically the ground planes of the illustrations of the second and third rounds of Inferno. Although the illustrations for the first three rounds depict different imagery, the vertical perspective links them into a single unit. The third round consists of the illustrations for cantos XV, XVI and XVII, which depict the punishment of those who sinned by violence against God, nature and art.[24]

Botticelli uses thirteen drawings to illustrate the eighth circle of Hell, depicting ten chasms that Dante and Virgil descend through a ridge.[2]

Dimensions

[edit]

Each page of the manuscript was approximately 32 cm high by 47 cm wide. Since the text of each canto was written on a single page and the accompanying illustration was on a separate page, arranging the two pages in a horizontal format would have been impractical as it would be approximately 94 centimetres (37 in) wide. This would entail the readers turning their heads from left to right while trying to connect the text columns on the left to the illustration on the right. A vertical arrangement, stacking the illustration page on top of the text page, is a more efficient way of combining the text-illustration pair; a volume designed to open vertically is a more probable scenario for Botticelli's manuscript. If the manuscript's binding were to open vertically, the dimensions would be approximately 47 centimetres (19 in) wide by 64 centimetres (25 in) high, and would incorporate both the text and the illustration on a single page. This would have made reading the text and looking at the drawing of each canto easier and more efficient.[26]

-

Purgatory X (10)

-

Purgatorio XVII

-

Purgatorio XXXI

-

Canto XXX

-

Canto XXXI

Content location

[edit]The Vatican Library has the drawing of the Map of Hell, and the illustrations for cantos I, IX, X, XII, XIII, XV and XVI of the Inferno. The Map of Hell and the drawing for canto I are drawn on each side of the same goat-skin parchment. The drawings that were in the Berlin Museum were separated post-war after the division of Germany, but the collection was re-integrated following reunification.[6] The Berlin Museum houses the rest of the extant illustrations, including the drawing for canto VIII. The sequence of the Inferno drawings for cantos XVII to canto XXX for Paradiso is without gaps. The page for the drawing of canto XXXI appears blank, and the sequence ends with the unfinished drawing for canto XXXII.[3]

Film

[edit]The 2016 film Botticelli Inferno is based on the history of the illustrated manuscript.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Watts, Barbara J. (1995). "Sandro Botticelli's Drawings for Dante's "Inferno": Narrative Structure, Topography, and Manuscript Design". Artibus et Historiae. 16 (32): 163–201. doi:10.2307/1483567. JSTOR 1483567.

The drawings' dates are uncertain, but he probably began them in the mid-1480s, and worked on them for an ex tended period, probably into the mid-1490s. 4 Unfortunately, he never finished the project. Many of the extant drawings are not fully fixed in pen, and only four of these contain illumination. 5 Nonetheless, Botticelli's Dante drawings are of such vision and beauty that, no less than the Primavera, they are central to his artistic achievement. In all likelihood, the cycle for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco's manuscript was Botticelli's second effort at illustrating Dante, the first being designs for the Florence Commedia, published by Nicholo di Lorenzo della Magna in 1481 [Fig. 2]. 6 The engravings for Inferno I through XIX that were printed for this edition have long been attributed to Baccio Baldini, who according to Vasari, had no invenzione and relied exclusively on Botticelli for his designs. 7 The similarities between these engravings and Botticelli's Inferno drawings support the assumption that Botticelli made the designs Baldini used. If he did, the engravings are especially significant because they provide a sense of what the lost drawings for Inferno II-VIII and XIV looked like.

- ^ a b Watts, Barbara J. (1995). "Sandro Botticelli's Drawings for Dante's "Inferno": Narrative Structure, Topography, and Manuscript Design". Artibus et Historiae. 16 (32): 182. doi:10.2307/1483567. JSTOR 1483567.

The eighth circle is made up of a series of ten descending chasms (the Malebolge) that Dante and Virgil cross by a continuous ridge, which extends from the top to the bottom of the circle (XVIII:14–18).46 In the thirteen illustrations for this circle, Botticelli consistently placed these ponti on the right side of the composition, breaking the pattern only when the narrative required it or when rendering a chasm for the second time [XVIII-XXXI, Figs. 17–27].

- ^ a b c Lippmann, F. (1896). Drawings by Sandro Botticelli for Dante's Divina Commedia. Lawrence and Bullen London. p. 16.

Not only does the general character of these drawings at once suggest Botticelli, but a careful study of their details confirms the belief that they were entirely executed by him. We recognize throughout the specific character of his art as manifested in his best pictures, [...]

- ^ a b c Lippmann, F. (1896). Drawings by Sandro Botticelli for Dante's Divina Commedia. Lawrence and Bullen London. p. 15.

There are 88 sheets in the Berlin group, 85 of them illustrated. These were in an 18th-century binding. The Vatican group is 8 drawings on 7 sheets; the introductory map of Hell is on the same sheet as the first illustration to Canto 1, on the reverse.

- ^ Havely, R. N., Dante's British Public: Readers and Texts, from the Fourteenth Century to the Present, pp. 244–259, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0199212449, 9780199212446, google books

- ^ a b Nigel Reynolds (7 September 2000). "Royal Academy wins battle over Botticellis". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Lightbown, pp. 86-89

- ^ Lippmann, F. (1896). Drawings by Sandro Botticelli for Dante's Divina Commedia. Lawrence and Bullen London. p. 20.

It is very probable that Botticelli began the Dante drawings before he went to Rome in 1481. Vasari says that "he illustrated the Inferno, and caused it to be printed". Now we do possess an edition of the Divine Comedy, printed in Florence in 1481, in which the Inferno is illustrated with nineteen little engravings. The affinity between these plates and Botticelli's drawings is unmistakable. This edition, published under the direction of Cristophoro Landino, and furnished with his commentary on the poem*, it was originally proposed to illustrate with engravings throughout.

- ^ Landau, 35, 38

- ^ Vasari, 152

- ^ Lightbown, 89; Landau, 108; Dempsey

- ^ Lightbown, 90, 94

- ^ a b Watts, Barbara J. (1995). "Sandro Botticelli's Drawings for Dante's "Inferno": Narrative Structure, Topography, and Manuscript Design". Artibus et Historiae. 16 (32): 193. doi:10.2307/1483567. JSTOR 1483567.

- ^ Lightbown, 282

- ^ Ettlingers, 178-179

- ^ Ettlingers, 178–179; Lightbown, 294

- ^ Lightbown, 282, 290

- ^ Lightbown, 282–290, 295

- ^ Lightbown, 296

- ^ Lightbown, 290

- ^ Lightbown, 280

- ^ Lightbown, 280-296

- ^ Lightbown, 282; Ettlingers, 179

- ^ a b Watts, Barbara J. (1995). "Sandro Botticelli's Drawings for Dante's "Inferno": Narrative Structure, Topography, and Manuscript Design". Artibus et Historiae. 16 (32): 180. doi:10.2307/1483567. JSTOR 1483567.

This formula is maintained in the extant illustrations for the third round, where those violent against God, nature, and art are punished [XV-XVII, Figs. 14–16. [...] page. By rendering vertically the planes of the second and third rounds, Botticelli linked their illustrations to that for the first round in which the space actually is perpendicular.

- ^ a b c Watts, Barbara J. (1995). "Sandro Botticelli's Drawings for Dante's "Inferno": Narrative Structure, Topography, and Manuscript Design". Artibus et Historiae. 16 (32): 195–197. doi:10.2307/1483567. JSTOR 1483567.

- ^ a b Watts, Barbara J. (1995). "Sandro Botticelli's Drawings for Dante's "Inferno": Narrative Structure, Topography, and Manuscript Design". Artibus et Historiae. 16 (32): 198. doi:10.2307/1483567. JSTOR 1483567.

From here, the step to a volume that opened vertically is almost inevitable when practical and aesthetic concerns are coupled with the nature of Botticelli's illustrations and the content of Dante's poem. A conventionally bound manuscript composed of sheets measuring over 32 cm. high and over 47 cm. wide, would, when open, have a breadth of at least 94 cm. [...] A manuscript bound so as to open vertically would have none of the aforementioned shortcomings. When open, it would measure approximately 64 cm. in height and only 47 cm. across, a more manageable size. With the text below and the illumination above, the text would be easy to read and the illustration close at hand for detailed scrutiny [...] This drawing thus binds the series together: the cosmographical plan of Hell that is presented in its first image is completed in the last, which in turn provides the geographical bridge to the mountain of Purgatory and the second stage of Dante's journey. This relation between the first and final images of the Inferno confirms a cohesive plan for the manuscript, a plan grounded in the manuscript's pictorial cycle.

References

[edit]- Dempsey, Charles, "Botticelli, Sandro", Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 15 May. 2017. subscription required

- "Ettlingers": Leopold Ettlinger with Helen S. Ettlinger, Botticelli, 1976, Thames and Hudson (World of Art), ISBN 0500201536

- Landau, David, in Landau, David, and Parshall, Peter. The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0300068832

- Lightbown, Ronald, Sandro Botticelli: Life and Work, 1989, Thames and Hudson

- Vasari, selected & ed. George Bull, Artists of the Renaissance, Penguin 1965 (page nos from BCA edn, 1979). Vasari Life on-line (in a different translation)

Further reading

[edit]- Gentile, Sebastiano (vol 1) and Schulze Altcappenberg, Heinrich-Thomas, Sandro Botticelli: pittore della Divina Commedia, in 2 volumes (facsimile with scholarly introductions), 2000, Skira (vol 1), Scuderie Papali al Quirinale and Royal Academy of Arts (vol 2)

- Plazzotta, C. (2001). Review: "Botticelli and Dante: Berlin, Rome and London", The Burlington Magazine, 143(1177), 239–241. JSTOR

- Schulze Altcappenberg, Heinrich-Thomas, Sandro Botticelli: The Drawings for Dante's Divine Comedy, 2000, Royal Academy/Harry N Abrams, catalogue for the exhibition, ISBN 0810966336, 9780810966338

External links

[edit] Media related to Sandro Botticelli's illustrations to the Divine Comedy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sandro Botticelli's illustrations to the Divine Comedy at Wikimedia Commons

KSF

KSF