Domesday Book

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 23 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 23 min

| Domesday Book | |

|---|---|

| The National Archives, Kew, London | |

Domesday Book: an engraving published in 1900. Great Domesday (the larger volume) and Little Domesday (the smaller volume), in their 1869 bindings, lie on their older "Tudor" bindings. | |

| Also known as |

|

| Date | 1086 |

| Place of origin | England |

| Language(s) | Medieval Latin |

Domesday Book (/ˈduːmzdeɪ/ DOOMZ-day; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of King William the Conqueror.[1] The manuscript was originally known by the Latin name Liber de Wintonia, meaning "Book of Winchester", where it was originally kept in the royal treasury.[2] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that in 1085 the king sent his agents to survey every shire in England, to list his holdings and dues owed to him.[3]

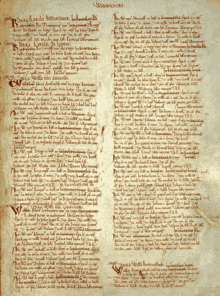

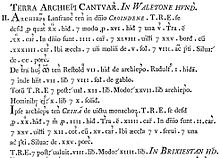

Written in Medieval Latin, it was highly abbreviated[a] and included some vernacular native terms without Latin equivalents. The survey's main purpose was to record the annual value of every piece of landed property to its lord, and the resources in land, labour force, and livestock from which the value derived.

The name "Domesday Book" came into use in the 12th century.[4] Richard FitzNeal wrote in the Dialogus de Scaccario (c. 1179) that the book was so called because its decisions were unalterable, like those of the Last Judgment, and its sentence could not be quashed.[5]

The manuscript is held at the National Archives at Kew, London. Domesday was first printed in full in 1783, and in 2011 the Open Domesday site made the manuscript available online.[6]

The book is an invaluable primary source for modern historians and historical economists. No survey approaching the scope and extent of Domesday Book was attempted again in Britain until the 1873 Return of Owners of Land (sometimes termed the "Modern Domesday")[7] which presented the first complete, post-Domesday picture of the distribution of landed property in the United Kingdom.[8]

Content and organisation

[edit]Domesday Book encompasses two independent works (originally in two physical volumes): "Little Domesday" (covering Norfolk, Suffolk, and Essex), and "Great Domesday" (covering much of the remainder of England – except for lands in the north that later became Westmorland, Cumberland, Northumberland, and the County Palatine of Durham – and parts of Wales bordering and included within English counties).[9] Space was left in Great Domesday for a record of the City of London and Winchester, but they were never written up. Other areas of modern London were then in Middlesex, Surrey, Kent, and Essex and have their place in Domesday Book's treatment of those counties. Most of Cumberland, Westmorland, and the entirety of the County Palatine of Durham and Northumberland were omitted. They did not pay the national land tax called the geld, and the framework for Domesday Book was geld assessment lists.[10][11]

"Little Domesday", so named because its format is physically smaller than its companion's, is more detailed than Great Domesday. In particular, it includes the numbers of livestock on the home farms (demesnes) of lords, but not peasant livestock. It represents an earlier stage in processing the results of the Domesday Survey before the drastic abbreviation and rearrangement undertaken by the scribe of Great Domesday Book.[12]

Both volumes are organised into a series of chapters (literally "headings", from Latin caput, "a head") listing the manors held by each named tenant-in-chief directly from the king. Tenants-in-chief included bishops, abbots and abbesses, barons from Normandy, Brittany, and Flanders, minor French serjeants, and English thegns. The richest magnates held several hundred manors typically spread across England, though some large estates were highly concentrated. For example, Baldwin the Sheriff had one hundred and seventy-six manors in Devon and four nearby in Somerset and Dorset. Tenants-in-chief held variable proportions of their manors in demesne, and had subinfeudated to others, whether their own knights (often tenants from Normandy), other tenants-in-chief of their own rank, or members of local English families. Manors were generally listed within each chapter by the hundred or wapentake in which they lay, hundreds (wapentakes in eastern England) being the second tier of local government within the counties.

Each county's list opened with the king's demesne, which had possibly been the subject of separate inquiry.[clarification needed] Under the feudal system, the king was the only true "owner" of land in England by virtue of his allodial title. He was thus the ultimate overlord, and even the greatest magnate could do no more than "hold" land from him as a tenant (from the Latin verb tenere, "to hold") under one of the various contracts of feudal land tenure. Holdings of bishops followed, then of abbeys and religious houses, then of lay tenants-in-chief, and lastly the king's serjeants (servientes) and thegns.

In some counties, one or more principal boroughs formed the subject of a separate section. A few have separate lists of disputed titles to land called clamores (claims). The equivalent sections in Little Domesday are called Inuasiones (annexations).

In total, 268,984 people are tallied in the Domesday Book, each of whom was the head of a household. Some households, such as urban dwellers, were excluded from the count, but the exact parameters remain a subject of historical debate. Sir Michael Postan, for instance, contends that these may not represent all rural households, but only full peasant tenancies, thus excluding landless men and some subtenants (potentially a third of the country's population). H. C. Darby, when factoring in the excluded households and using various different criteria for those excluded (as well as varying sizes for the average household), concludes that the 268,984 households listed most likely indicate a total English population between 1.2 and 1.6 million.[13]

Domesday names a total of 13,418 places.[14] Apart from the wholly rural portions, which constitute its bulk, Domesday contains entries of interest concerning most towns, which were probably made because of their bearing on the fiscal rights of the crown therein. These include fragments of custumals (older customary agreements), records of the military service due, markets, mints, and so forth. From the towns, from the counties as wholes, and from many of its ancient lordships, the crown was entitled to archaic dues in kind, such as honey.

The Domesday Book lists 5,624 mills in the country, which is considered a low estimate since the book is incomplete. For comparison, fewer than 100 mills were recorded[where?] in the country a century earlier. Georges Duby indicates this means a mill for every forty-six peasant households and implies a great increase in the consumption of baked bread in place of boiled and unground porridge.[15] The book also lists 28,000 slaves, a smaller number than had been enumerated in 1066.[16]

In the Domesday Book, scribes' orthography was heavily geared towards French, most lacking k and w, regulated forms for sounds /ð/ and /θ/ and ending many hard consonant words with e as they were accustomed to do with most dialects of French at the time.

Similar works

[edit]In a parallel development, around 1100, the Normans in southern Italy completed their Catalogus Baronum based on Domesday Book. The original manuscript was destroyed in the Second World War, but the text survives in printed editions.[17]

Name

[edit]The manuscripts do not carry a formal title. The work is referred to internally as a descriptio (enrolling), and in other early administrative contexts as the king's brevia ((short) writings). From about 1100, references appear to the liber (book) or carta (charter) of Winchester, its usual place of custody; and from the mid-12th to early 13th centuries to the Winchester or king's rotulus (roll).[18][19]

To the English, who held the book in awe, it became known as "Domesday Book", in allusion to the Last Judgment and in specific reference to the definitive character of the record.[20] The word "doom" was the usual Old English term for a law or judgment; it did not carry the modern overtones of fatality or disaster.[21] Richard FitzNeal, treasurer of England under Henry II, explained the name's connotations in detail in the Dialogus de Scaccario (c.1179):[22]

The natives call this book "Domesday", that is, the day of judgement. This is a metaphor: for just as no judgement of that final severe and terrible trial can be evaded by any subterfuge, so when any controversy arises in the kingdom concerning the matters contained in the book, and recourse is made to the book, its word cannot be denied or set aside without penalty. For this reason we call this book the "book of judgements", not because it contains decisions made in controversial cases, but because from it, as from the Last Judgement, there is no further appeal.

The name "Domesday" was subsequently adopted by the book's custodians, being first found in an official document in 1221.[23]

Either through false etymology or deliberate word play, the name also came to be associated with the Latin phrase Domus Dei ("House of God"). Such a reference is found as early as the late 13th century, in the writings of Adam of Damerham; and in the 16th and 17th centuries, antiquaries such as John Stow and Sir Richard Baker believed this was the name's origin, alluding to the church in Winchester in which the book had been kept.[24][25] As a result, the alternative spelling "Domesdei" became popular for a while.[26]

The usual modern scholarly convention is to refer to the work as "Domesday Book" (or simply as "Domesday"), without a definite article. However, the form "the Domesday Book" is also found in both academic and non-academic contexts.[27]

Survey

[edit]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that planning for the survey was conducted in 1085, and the book's colophon states the survey was completed in 1086. It is not known when exactly Domesday Book was compiled, but the entire copy of Great Domesday appears to have been copied out by one person on parchment (prepared sheepskin), although six scribes seem to have been used for Little Domesday. Writing in 2000, David Roffe argued that the inquest (survey) and the construction of the book were two distinct exercises. He believes the latter was completed, if not started, by William II following his accession to the English throne; William II quashed a rebellion that followed and was based on, though not consequence of, the findings of the inquest.[28]

Most shires were visited by a group of royal officers (legati) who held a public inquiry, probably in the great assembly known as the shire court. These were attended by representatives of every township as well as of the local lords. The unit of inquiry was the Hundred (a subdivision of the county, which then was an administrative entity). The return for each Hundred was sworn to by 12 local jurors, half of them English and half of them Norman.

What is believed to be a full transcript of these original returns is preserved for several of the Cambridgeshire Hundreds – the Cambridge Inquisition – and is of great illustrative importance. The Inquisitio Eliensis is a record of the lands of Ely Abbey.[29] The Exon Domesday (named because the volume was held at Exeter) covers Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, and one manor of Wiltshire. Parts of Devon, Dorset, and Somerset are also missing. Otherwise, this contains the full details supplied by the original returns.

Through comparison of what details are recorded in which counties, six Great Domesday "circuits" can be determined (plus a seventh circuit for the Little Domesday shires).

- Berkshire, Hampshire, Kent, Surrey, Sussex

- Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Wiltshire

- Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire, Middlesex

- Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire, Staffordshire, Warwickshire

- Cheshire, the land Inter Ripam et Mersham ("between Ribble and Mersey", now much of south Lancashire), Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, Shropshire, Worcestershire – the Marches

- Derbyshire, Huntingdonshire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Rutland,[30] Yorkshire

Purpose

[edit]Three sources discuss the goal of the survey[original research?]:

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells why it was ordered:[3]

After this had the king a large meeting, and very deep consultation with his council, about this land; how it was occupied, and by what sort of men. Then sent he his men over all England into each shire; commissioning them to find out 'How many hundreds of hides were in the shire, what land the king himself had, and what stock upon the land; or, what dues he ought to have by the year from the shire.' Also he commissioned them to record in writing, 'How much land his archbishops had, and his diocesan bishops, and his abbots, and his earls;' and though I may be prolix and tedious, 'What, or how much, each man had, who was an occupier of land in England, either in land or in stock, and how much money it was worth.' So very narrowly, indeed, did he commission them to trace it out, that there was not one single hide, nor a yard of land, nay, moreover (it is shameful to tell, though he thought it no shame to do it), not even an ox, nor a cow, nor a swine was there left, that was not set down in his writ. And all the recorded particulars were afterwards brought to him.

- The list of questions asked of the jurors was recorded in the Inquisitio Eliensis.

- The contents of Domesday Book and the allied records mentioned above.

The primary purpose of the survey was to ascertain and record the fiscal rights of the king. These were mainly:

- the national land-tax (geldum), paid on a fixed assessment;

- certain miscellaneous dues; and

- the proceeds of the crown lands.

After a great political convulsion such as the Norman Conquest, and the following wholesale confiscation of landed estates, William needed to reassert that the rights of the Crown, which he claimed to have inherited, had not suffered in the process. His Norman followers tended to evade the liabilities of their English predecessors. Historians believe the survey was to aid William in establishing certainty and a definitive reference point as to property holdings across the nation, in case such evidence was needed in disputes over Crown ownership.[31]

The Domesday survey, therefore, recorded the names of the new holders of lands and the assessments on which their tax was to be paid. But it did more than this; by the king's instructions, it endeavoured to make a national valuation list, estimating the annual value of all the land in the country, (1) at the time of Edward the Confessor's death, (2) when the new owners received it, (3) at the time of the survey, and further, it reckoned, by command, the potential value as well. It is evident that William desired to know the financial resources of his kingdom, and it is probable that he wished to compare them with the existing assessment, which was one of considerable antiquity, though there are traces that it had been occasionally modified. The great bulk of Domesday Book is devoted to the somewhat arid details of the assessment and valuation of rural estates, which were as yet the only important source of national wealth. After stating the assessment of the manor, the record sets forth the amount of arable land, and the number of plough teams (each reckoned at eight oxen) available for working it, with the additional number (if any) that might be employed; then the river-meadows, woodland, pasture, fisheries (i.e. fishing weirs), water-mills, salt-pans (if by the sea), and other subsidiary sources of revenue; the peasants are enumerated in their several classes; and finally the annual value of the whole, past and present, is roughly estimated.

The organisation of the returns on a feudal basis, enabled the Conqueror and his officers to see the extent of a baron's possessions; and it also showed to what extent he had under-tenants and the identities of the under-tenants. This was of great importance to William, not only for military reasons but also because of his resolve to command the personal loyalty of the under-tenants (though the "men" of their lords) by making them swear allegiance to him. As Domesday Book normally records only the Christian name of an under-tenant, it is not possible to search for the surnames of families claiming a Norman origin. Scholars, however, have worked to identify the under-tenants, most of whom have foreign Christian names.

The survey provided the King with information on potential sources of funds when he needed to raise money. It includes sources of income but not expenses, such as castles, unless they needed to be included to explain discrepancies between pre-and post-Conquest holdings of individuals. Typically, this happened in a town, where separately-recorded properties had been demolished to make way for a castle.

Early British authors thought that the motivation behind the Survey was to put into William's power the lands, so that all private property in land came only from the grant of King William, by lawful forfeiture.[32] The use of the word antecessor in the Domesday Book is used for the former holders of the lands under Edward, and who had been dispossessed by their new owners.[33]

Subsequent history

[edit]

Custodial history

[edit]Domesday Book was preserved from the late 11th to the beginning of the 13th centuries in the royal Treasury at Winchester (the Norman kings' capital). It was often referred to as the "Book" or "Roll" of Winchester.[18] When the Treasury moved to the Palace of Westminster, probably under King John, the book went with it.

The two volumes (Great Domesday and Little Domesday) remained in Westminster, save for temporary releases, until the 19th century. They were held originally in various offices of the Exchequer: the Chapel of the Pyx of Westminster Abbey; the Treasury of Receipts; and the Tally Court.[34] However, on several occasions they were taken around the country with the Chancellor of the Exchequer: to York and Lincoln in 1300, to York in 1303 and 1319, to Hertford in the 1580s or 1590s, and to Nonsuch Palace, Surrey, in 1666 for a time after the Great Fire of London.[35]

From the 1740s onwards, they were held, with other Exchequer records, in the chapter house of Westminster Abbey.[36] In 1859, they were transferred to the new Public Record Office, London.[37] They are now held at the National Archives at Kew. The chest in which they were stowed in the 17th and 18th centuries is also at Kew.

In modern times, the books have been removed from the London area only rarely. In 1861–1863, they were sent to Southampton for photozincographic reproduction.[38] In 1918–19, prompted by the threat of German bombing during the First World War, they were evacuated (with other Public Record Office documents) to Bodmin Prison, Cornwall. Likewise, in 1939–1945, during the Second World War, they were evacuated to Shepton Mallet Prison, Somerset.[39][40]

Binding

[edit]The volumes have been rebound on several occasions. Little Domesday was rebound in 1320, its older oak boards being re-used. At a later date (probably in the Tudor period) both volumes were given new covers. They were rebound twice in the 19th century, in 1819 and 1869 – on the second occasion, by the binder Robert Riviere and his assistant, James Kew. In the 20th century, they were rebound in 1952, when their physical makeup was examined in greater detail; and yet again in 1986, for the survey's ninth centenary. On this last occasion Great Domesday was divided into two physical volumes, and Little Domesday into three volumes.[41][42]

Publication

[edit]

The project to publish Domesday was begun by the government in 1773, and the book appeared in two volumes in 1783, set in "record type" to produce a partial-facsimile of the manuscript. In 1811, a volume of indexes was added. In 1816, a supplementary volume, separately indexed, was published containing

- The Exon Domesday – for the south-western counties

- The Inquisitio Eliensis

- The Liber Winton – surveys of Winchester late in the 12th century.

- The Boldon Buke (Book) – a survey of the bishopric of Durham a century later than Domesday

Photographic facsimiles of Domesday Book, for each county separately, were published in 1861–1863, also by the government. Today, Domesday Book is available in numerous editions, usually separated by county and available with other local history resources.

In 1986, the BBC released the BBC Domesday Project, the results of a project to create a survey to mark the 900th anniversary of the original Domesday Book. In August 2006, the contents of Domesday went online, with an English translation of the book's Latin. Visitors to the website are able to look up a place name and see the index entry made for the manor, town, city or village. They can also, for a fee, download the relevant page.

Continuing legal use

[edit]In the Middle Ages, the Book's evidence was frequently invoked in the law courts.[43] In 1960, it was among citations for a real manor which helps to evidence legal use rights on and anchorage into the Crown's foreshore;[44][45] in 2010, as to proving a manor, adding weight of years to sporting rights (deer and foxhunting);[46] and a market in 2019.[47]

Importance

[edit]

Domesday Book is critical to understanding the period in which it was written. As H. C. Darby noted, anyone who uses it

can have nothing but admiration for what is the oldest 'public record' in England and probably the most remarkable statistical document in the history of Europe. The continent has no document to compare with this detailed description covering so great a stretch of territory. And the geographer, as he turns over the folios, with their details of population and of arable, woodland, meadow and other resources, cannot but be excited at the vast amount of information that passes before his eyes.[48]

The author of the article on the book in the eleventh edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica noted, "To the topographer, as to the genealogist, its evidence is of primary importance, as it not only contains the earliest survey of each township or manor, but affords, in the majority of cases, a clue to its subsequent descent."

Darby also notes the inconsistencies, saying that "when this great wealth of data is examined more closely, perplexities and difficulties arise."[49] One problem is that the clerks who compiled this document "were but human; they were frequently forgetful or confused." The use of Roman numerals also led to countless mistakes. Darby states, "Anyone who attempts an arithmetical exercise in Roman numerals soon sees something of the difficulties that faced the clerks."[49] But more important are the numerous obvious omissions, and ambiguities in presentation. Darby first cites F. W. Maitland's comment following his compilation of a table of statistics from material taken from the Domesday Book survey, "it will be remembered that, as matters now stand, two men not unskilled in Domesday might add up the number of hides in a county and arrive at very different results because they would hold different opinions as to the meanings of certain formulas which are not uncommon."[50] Darby says that "it would be more correct to speak not of 'the Domesday geography of England', but of 'the geography of Domesday Book'. The two may not be quite the same thing, and how near the record was to reality we can never know."[49]

See also

[edit]- BBC Domesday Project – Crowdsourced born-digital description of the UK, published in 1986

- Cestui que – Concept in English law regarding beneficiaries

- Medieval demography – Human demography in Europe and the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages

- Quia Emptores – English statute of 1290

- Return of Owners of Land, 1873 – Survey of land ownership in the United Kingdom

- Taxatio – Valuation for ecclesiastical taxation

- Photozincography of Domesday Book

- Publication of Domesday Book

Notes

[edit]- ^ One common abbreviation was TRE, short for the Latin Tempore Regis Eduuardi, "in the time of King Edward (the Confessor)", meaning the period immediately before the Norman Conquest.

References

[edit]- ^ "Domesday Book". Merriam-Webster Online. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ "Domesday Book". Dictionary.com.

- ^ a b The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Translated by Giles, J. A.; Ingram, J. Project Gutenberg. 1996. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo & Burkholder, Robert E. (Notes) (1971). The Collected Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson: English Traits. Vol. 5. Harvard University Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0674139923. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Johnson, C., ed. (1950). Dialogus de Scaccario, the Course of the Exchequer, and Constitutio Domus Regis, the King's Household. London. p. 64.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cellan-Jones, Rory (13 May 2011). "Domesday Reloaded project: The 1086 version". BBC News. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ Hoskins, W.G. (1954). A New Survey of England. Devon, London. p. 87.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), - ^ Return of Owners of Land, 1873, Wales, Scotland, Ireland. 1873. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ "Hull Domesday Project: Wales". Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Darby, Henry Clifford (1986). Domesday England. Cambridge University Press. p. 2.

- ^ Stenton, Frank Merry (1971). Anglo-Saxon England. Clarendon Press. p. 645.

- ^ "Domesday Book". The National Archives. 27 July 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

Great Domesday contains most of the counties of England and was written by one scribe and checked by a second. Little Domesday, which contains the information for Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk, was probably written first and is the work of at least six scribes.

- ^ Robert Bartlett. "The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization, and Cultural Change, 950-1350."Princeton University Press; First PB Edition (August 23, 1994). p. 108.

- ^ "The Domesday Book". History Magazine. Moorshead Magazines. October 2001. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ Gies, Frances; Gies, Joseph (1994). Cathedral, Forge, and Waterwheel: Technology and Invention in the Middle Ages. HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. p. 113. ISBN 0060165901.

- ^ Clanchy, M. T. (2006). England and its Rulers: 1066–1307. Blackwell Classic Histories of England (Third ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-4051-0650-4.

- ^ Jamison, Evelyn (1971). "Additional Work on the Catalogus Baronum". Bullettino dell'Istituto Storico Italiano per Il Medioevo e Archivio Muratoriano. 83: 1–63.

- ^ a b Hallam 1986, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Harvey 2014, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Harvey 2014, pp. 271–328.

- ^ Harvey 2014, p. 271.

- ^ fitzNigel, Richard (2007). Amt, Emilie; Church, S. D. (eds.). Dialogus de Scaccario: the Dialogue of the Exchequer; Constitutio Domus Regis: Disposition of the King's Household. Oxford Medieval Texts. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 96–99. ISBN 9780199258611.

- ^ Hallam 1986, p. 35.

- ^ Hallam 1986, p. 34.

- ^ Harvey 2014, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Hallam 1986, p. 118.

- ^ "The Domesday Book Online". Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ Roffe, David (2000). Domesday; The Inquest and The Book. Oxford University Press. pp. 224–49.

- ^ "Inquisitio Eliensis". Domesday Explorer. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ Sometimes considered part of Nottinghamshire in this period.

- ^ Cooper, Alan (2001). "Extraordinary privilege: The trial of Penenden Heath and the Domesday inquest". English Historical Review. 116 (469): 1167–92. doi:10.1093/ehr/116.469.1167.

- ^ Freeman, Edward A., William the Conqueror, pp. 186–187

- ^ Freeman, Edward A., William the Conqueror, p. 188

- ^ Hallam 1986, p. 55.

- ^ Hallam 1986, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Hallam 1986, pp. 133–34.

- ^ Hallam 1986, pp. 150–52.

- ^ Hallam 1986, pp. 155–56.

- ^ Hallam 1986, pp. 167–69.

- ^ Cantwell, John D. (1991). The Public Record Office, 1838–1958. London: HMSO. pp. 379, 428–30. ISBN 0114402248.

- ^ Hallam 1986, pp. 29, 150–51, 157–61, 170–72.

- ^ Forde, Helen (1986). Domesday Preserved. London: Public Record Office. ISBN 0-11-440203-5.

- ^ Hallam 1986, pp. 50–55, 64–73.

- ^ "Early census-taking in England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Iveagh v Martin [and another] [1961] 1 Q.B. 232; [1960] 3 WLR 210; [1960] 2 All ER 668; 1 Lloyd's Rep. 692 QDB (1960)

- ^ Mellestrom v Badgworthy Land Company (adverse possession over continued common) [2010] EWLandRA 2008_1498 (21 July 2010) https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/format.cgi?doc=/ew/cases/EWLandRA/2010/2008_1498.html Archived 24 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Harvey, R (on the application of) v Leighton Linslade Town Council [2019] EWHC 760 (Admin) (15 February 2019) URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2019/760.html Archived 26 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Darby, Domesday England (Cambridge: University Press, 1977), p. 12

- ^ a b c Darby, Domesday England, p. 13

- ^ Maitland, Domesday Book and Beyond (Cambridge, 1897), p. 407

Bibliography

[edit]- Darby, Henry C. (1977). Domesday England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-31026-1.

- Domesday Book: A Complete Translation. London: Penguin. 2003. ISBN 0-14-143994-7.

- 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica: "Domesday Book" at Wikisource

- Freeman, Edward A. (1888). William the Conqueror. London: MacMillan and Co. OCLC 499742406.

- Hallam, Elizabeth M. (1986). Domesday Book through Nine Centuries. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0500250979.

- Harvey, Sally (2014). Domesday: Book of Judgement. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966978-3.

- Holt, J. C. (1987). Domesday Studies. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-263-5.

- Keats-Rohan, Katherine S. B. (1999). Domesday People: A Prosopography of Persons Occurring in English Documents, 1066–1166 (2v). Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press.

- Lennard, Reginald (1959). Rural England 1086–1135: A Study of Social and Agrarian Conditions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821272-0.

- Maitland, F. W. (1988). Domesday Book and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34918-4.

- Roffe, David (2000). Domesday: The Inquest and The Book. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820847-2.

- Roffe, David (2007). Decoding Domesday. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-307-9.

- Roffe, David; Keats-Rohan, Katharine (2016). Domesday Now: New Approaches to the Inquest and the Book. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-088-0.

- Vinogradoff, Paul (1908). English Society in the Eleventh Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Wood, Michael (2005). The Domesday Quest: In Search of the Roots of England. London: BBC Books. ISBN 0-563-52274-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Bates, David (1985). A Bibliography of Domesday Book. Woodbridge: Boydell. ISBN 0-85115-433-6.

- Bridbury, A. R. (1990). "Domesday Book: a re-interpretation". English Historical Review. 105: 284–309. doi:10.1093/ehr/cv.ccccxv.284.

- Darby, Henry C. (2003). The Domesday Geography of Eastern England. Domesday Geography of England. Vol. 1 (revised 3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521893968.

- Darby, Henry C.; Terrett, I. B., eds. (1971). The Domesday Geography of Midland England. Domesday Geography of England. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521080789.

- Darby, Henry C.; Campbell, Eila M. J., eds. (1961). The Domesday Geography of South-East England. Domesday Geography of England. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521047706.

- Darby, Henry C.; Maxwell, I. S., eds. (1977). The Domesday Geography of Northern England. Domesday Geography of England. Vol. 4 (corrected ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521047730.

- Darby, Henry C.; Finn, R. Welldon, eds. (1979). The Domesday Geography of South West England. Domesday Geography of England. Vol. 5 (corrected ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521047714.

- Delabastita, Vincent; Maes, Sebastiaan (2023). "The Feudal Origins of Manorial Prosperity: Social Interactions in Eleventh-Century England". The Journal of Economic History.

- Finn, R. Welldon (1973). Domesday Book: a guide. London: Phillimore. ISBN 0-85033-101-3.

- Snooks, Graeme D.; McDonald, John (1986). Domesday Economy: a new approach to Anglo-Norman history. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-828524-8.

- Hamshere, J. D. (1987). "Regressing Domesday Book: tax assessments of Domesday England". Economic History Review. n.s. 40 (2): 247–51. doi:10.2307/2596690. JSTOR 2596690.

- Leaver, R. A. (1988). "Five hides in ten counties: a contribution to the Domesday regression debate". Economic History Review. n.s. 41 (4): 525–42. doi:10.2307/2596600. JSTOR 2596600.

- McDonald, John; Snooks, G. D. (1985). "Were the tax assessments of Domesday England artificial?: the case of Essex". Economic History Review. n.s. 38 (3): 352–72. doi:10.2307/2596992. JSTOR 2596992.

- Sawyer, Peter, ed. (1985). Domesday Book: a reassessment. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 0713164409.

External links

[edit]- Online Edition of Domesday Book, housed on the National Archives website. Searchable; downloads are charged.

- Searchable index of landholders in 1066 and 1087, Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England (PASE) project.

- Focus on Domesday, from Learning Curve. Annotated sample page.

- Secrets of the Norman Invasion Domesday analysis of wasted manors.

- Domesday Book place-name forms – All the original spellings of English place-names in Domesday Book (link to PDF file).

- Commercial site with extracts from Domesday Book Archived 27 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine Domesday Book entries including translations for each settlement.

- Open Domesday Interactive map, listing details of each manor or holdings of each tenant, plus high-resolution images of the original manuscript. Site by Anna Powell-Smith, Domesday data created by Professor John J. N. Palmer, University of Hull.

- In Our Time – "The Domesday Book". BBC Radio 4 programme available on iPlayer

- Domesday Book and Cambridgeshire

- Doomsday Book at The Manor of Hunningham

KSF

KSF