Down syndrome

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 55 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 55 min

| Down syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Down's syndrome, Down's, trisomy 21 |

| |

| An eight-year-old boy displaying characteristic facial features of Down syndrome | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics, pediatrics |

| Symptoms | Delayed development, characteristic physical features, mild to moderate intellectual disability[1] |

| Usual onset | Mostly at conception, rarely after fertilization[2] |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Causes | Third copy of chromosome 21[3] |

| Risk factors | Older age of mother, prior affected child[4][5] |

| Diagnostic method | Prenatal screening, genetic testing[6] |

| Treatment | Physical therapy, Occupational therapy, Speech therapy, Educational support, Supported work environment[7][8] |

| Prognosis | Life expectancy 50 to 60 years (developed world)[9][10] |

| Frequency | 5.4 million (0.1%)[1][11] |

| Named after | John Langdon Down |

Down syndrome or Down's syndrome,[12] also known as trisomy 21, is a genetic disorder caused by the presence of all or part of a third copy of chromosome 21.[3] It is usually associated with developmental delays, mild to moderate intellectual disability, and characteristic physical features.[1][13]

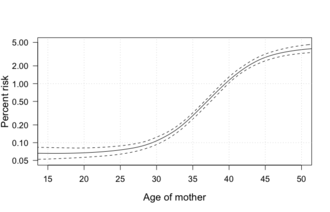

The parents of the affected individual are usually genetically normal.[14] The incidence of the syndrome increases with the age of the mother, from less than 0.1% for 20-year-old mothers to 3% for those of age 45.[4] It is believed to occur by chance, with no known behavioral activity or environmental factor that changes the probability.[2] Usually, babies get 23 chromosomes from each parent for a total of 46, whereas in Down syndrome, a third 21st chromosome is attached.[15] The extra chromosome is provided at conception as the egg and sperm combine.[16] In 1–2% of cases, the additional chromosome is added in the embryo stage and only impacts some of the cells in the body; this is known as Mosaic Down syndrome.[17][15] Translocation Down syndrome is another rare type.[18][19] Down syndrome can be identified during pregnancy by prenatal screening, followed by diagnostic testing, or after birth by direct observation and genetic testing.[6] Since the introduction of screening, Down syndrome pregnancies are often aborted (rates varying from 50 to 85% depending on maternal age, gestational age, and maternal race/ethnicity).[20][21][22]

There is no cure for Down syndrome.[23] Education and proper care have been shown to provide better quality of life.[7] Some children with Down syndrome are educated in typical school classes, while others require more specialized education.[8] Some individuals with Down syndrome graduate from high school, and a few attend post-secondary education.[24] In adulthood, about 20% in the United States do some paid work,[25] with many requiring a sheltered work environment.[8] Caretaker support in financial and legal matters is often needed.[10] Life expectancy is around 50 to 60 years in the developed world, with proper health care.[9][10] Regular screening for health issues common in Down syndrome is recommended throughout the person's life.[9]

Down syndrome is the most common chromosomal abnormality,[26] occurring in about 1 in 1,000 babies born worldwide,[1] and one in 700 in the US.[18] In 2015, there were 5.4 million people with Down syndrome globally, of whom 27,000 died, down from 43,000 deaths in 1990.[11][27][28] The syndrome is named after British physician John Langdon Down, who dedicated his medical practice to the cause.[29] Some aspects were described earlier by French psychiatrist Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol in 1838 and French physician Édouard Séguin in 1844.[30] The genetic cause was discovered in 1959.[29]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Those with Down syndrome nearly always have physical and intellectual disabilities.[31] As adults, their mental abilities are typically similar to those of an 8- or 9-year-old.[9] At the same time, their emotional and social awareness is very high.[32] They can have poor immune function[14] and generally reach developmental milestones at a later age.[10] They have an increased risk of a number of health concerns, such as congenital heart defect, epilepsy, leukemia, and thyroid diseases.[29]

| Characteristics | Percentage | Characteristics | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental impairment | 99%[33] | Abnormal teeth | 60%[34] |

| Stunted growth | 90%[35] | Slanted eyes | 60%[14] |

| Umbilical hernia | 90%[36] | Shortened hands | 60%[34] |

| Increased skin on back of neck | 80%[29] | Short neck | 60%[34] |

| Low muscle tone | 80%[37] | Obstructive sleep apnea | 60%[29] |

| Narrow roof of mouth | 76%[34] | Bent fifth finger tip | 57%[14] |

| Flat head | 75%[14] | Brushfield spots in the iris | 56%[14] |

| Flexible ligaments | 75%[14] | Single transverse palmar crease | 53%[14] |

| Proportionally large tongue[38] | 75%[37] | Protruding tongue | 47%[34] |

| Abnormal outer ears | 70%[29] | Congenital heart disease | 40%[34] |

| Flattened nose | 68%[14] | Strabismus | ≈35%[1] |

| Separation of first and second toes | 68%[34] | Undescended testicles | 20%[39] |

Physical

[edit]

People with Down syndrome may have these physical characteristics: a small chin, epicanthic folds, low muscle tone, a flat nasal bridge, and a protruding tongue. A protruding tongue is caused by low tone and weak facial muscles, and often corrected with myofunctional exercises.[40] Some characteristic airway features can lead to obstructive sleep apnea in around half of those with Down syndrome.[29] Other common features include: excessive joint flexibility, extra space between big toe and second toe, a single crease of the palm, and short fingers.[34][37]

Instability of the atlantoaxial joint occurs in about 1–2%.[41] Atlantoaxial instability may cause myelopathy due to cervical spinal cord compression later in life, this often manifests as new onset weakness, problems with coordination, bowel or bladder incontinence, and gait dysfunction.[42] Serial imaging cannot reliably predict future cervical cord compression, but changes can be seen on neurological exam. The condition is surgically corrected with spine surgery.[42]

Growth in height is slower, resulting in adults who tend to have short stature—the average height for men is 154 centimetres (5 feet 1 inch), and for women is 142 centimetres (4 feet 8 inches).[43] Individuals with Down syndrome are at increased risk for obesity as they age due to hypothyroidism, other medical issues and lifestyle.[29][44] Growth charts have been developed specifically for children with Down syndrome.[29]

Neurological

[edit]

This syndrome causes about a third of cases of intellectual disability.[14] Many developmental milestones are delayed with the ability to crawl typically occurring around 8–22 months rather than 6–12 months, and the ability to walk independently typically occurring around 1–4 years rather than 9–18 months.[45] Walking is acquired in 50% of children after 24 months.[46]

Most individuals with Down syndrome have mild (IQ: 50–69) or moderate (IQ: 35–50) intellectual disability with some cases having severe (IQ: 20–35) difficulties.[1][47] Those with mosaic Down syndrome typically have IQ scores 10–30 points higher than that.[48] As they age, the gap tends to widen between people with Down syndrome and their same-age peers.[47][49]

Commonly, individuals with Down syndrome have better language understanding than ability to speak.[29][47] Babbling typically emerges around 15 months on average.[50] 10–45% of those with Down syndrome have either a stutter or rapid and irregular speech, making it difficult to understand them.[51] After reaching 30 years of age, some may lose their ability to speak.[9]

They typically do fairly well with social skills.[29] Behavior problems are not generally as great an issue as in other syndromes associated with intellectual disability.[47] In children with Down syndrome, mental illness occurs in nearly 30% with autism occurring in 5–10%.[10] People with Down syndrome experience a wide range of emotions.[52] While people with Down syndrome are generally happy,[53] symptoms of depression and anxiety may develop in early adulthood.[9]

Children and adults with Down syndrome are at increased risk of epileptic seizures, which occur in 5–10% of children and up to 50% of adults.[9] This includes an increased risk of a specific type of seizure called infantile spasms.[29] Many (15%) who live 40 years or longer develop Alzheimer's disease.[54] In those who reach 60 years of age, 50–70% have the disease.[9]

Down syndrome regression disorder is a sudden regression with neuropsychiatric symptoms such as catatonia, possibly caused by an autoimmune disease.[55] It primarily appears in teenagers and younger adults.[56]

Senses

[edit]

Hearing and vision disorders occur in more than half of people with Down syndrome.[29]

Ocular findings

[edit]Brushfield spots (small white or grayish/brown spots on the periphery of the iris), upward slanting palpebral fissures (the opening between the upper and lower lids) and epicanthal folds (folds of skin between the upper eyelid and the nose) are clinical signs at birth suggesting the diagnosis of Down syndrome[57][58] especially in the Western World.[58] None of these requires treatment.[citation needed]

Visually significant congenital cataracts (clouding of the lens of the eye) occur more frequently with Down syndrome.[58] Neonates with Down syndrome should be screened for cataract because early recognition and referral reduce the risk of vision loss from amblyopia.[59] Dot-like opacities in the cortex of the lens (cerulean cataract) are present in up to 50% of people with Down syndrome, but may be followed without treatment if they are not visually significant.[58]

Strabismus, nystagmus and nasolacrimal duct obstruction occur more frequently in children with Down syndrome.[58] Screening for these diagnoses should begin within six months of birth.[58][59] Strabismus is more often acquired than congenital.[58] Early diagnosis and treatment of strabismus reduces the risk of vision loss from amblyopia.[60] In Down syndrome, the presence of epicanthal folds may give the false impression of strabismus, referred to as pseudostrabismus. Nasolacrimal duct obstruction, which causes tearing (epiphora), is more frequently bilateral and multifactorial than in children without Down syndrome.[58]

Refractive error is more common with Down syndrome, though the rate may not differ until after twelve months of age compared to children without Down syndrome.[58] Early screening is recommended to identify and treat significant refractive error with glasses or contact lenses. Poor accommodation (ability to focus on close objects) is associated with Down syndrome, which may mean bifocals are indicated.[58]

In keratoconus, the cornea progressively thins and bulges into a cone shape,[61] causing visual blurring or distortion. Keratoconus first presents in the teen years and progresses into the thirties.[61][62] Down syndrome is a strong risk factor for developing keratoconus, and onset may be occur at a younger age than in those without Down syndrome.[58] Eye rubbing is also a risk factor for developing keratoconus.[62] It is speculated that chronic eye irritation from blepharitis may increase eye rubbing in Down syndrome,[58] contributing to the increased prevalence of keratoconus.

An association between glaucoma and Down syndrome is often cited.[57] Glaucoma in children with Down syndrome is uncommon, with a prevalence of less than 1%.[57][58] It is currently unclear if the prevalence of glaucoma in those with Down syndrome differs from that in the absence of Down syndrome.[58]

Estimates of prevalence of ocular findings in Down Syndrome vary widely depending on the study.[58] Some prevalence estimates follow. Vision problems have been observed in 38–80% of cases.[57] Brushfield spots are present in 38–85% of individuals.[57] Between 20 and 50% have strabismus.[57] Cataracts occur in 15%,[63] and may be present at birth.[57] Keratoconus may occur in as many as 21–30%.[58]

Hearing loss

[edit]Hearing problems are found in 50–90% of children with Down syndrome.[64] This is often the result of otitis media with effusion which occurs in 50–70%[10] and chronic ear infections which occur in 40–60%.[65] Ear infections often begin in the first year of life and are partly due to poor eustachian tube function.[66][67] Excessive ear wax can also cause hearing loss due to obstruction of the outer ear canal.[9] Even a mild degree of hearing loss can have negative consequences for speech, language understanding, and academics.[1][67] It is important to rule out hearing loss as a factor in social and cognitive deterioration.[68] Age-related hearing loss of the sensorineural type occurs at a much earlier age and affects 10–70% of people with Down syndrome.[9]

Heart

[edit]The rate of congenital heart disease in newborns with Down syndrome is around 40%.[34] Of those with heart disease, about 80% have an atrial septal defect or ventricular septal defect with the former being more common.[9] Congenital heart disease can also put individuals at a higher risk of pulmonary hypertension, where arteries in the lungs narrow and cause inadequate blood oxygenation.[69] Some of the genetic contributions to pulmonary hypertension in individuals with Down Syndrome are abnormal lung development, endothelial dysfunction, and proinflammatory genes.[69] Mitral valve problems become common as people age, even in those without heart problems at birth.[9] Other problems that may occur include tetralogy of Fallot and patent ductus arteriosus.[66] People with Down syndrome have a lower risk of hardening of the arteries.[9]

Cancer

[edit]Although the overall risk of cancer in Down syndrome is not changed,[70] the risk of testicular cancer and certain blood cancers, including acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL) is increased while the risk of other non-blood cancers is decreased.[9] People with Down syndrome are believed to have an increased risk of developing cancers derived from germ cells whether these cancers are blood- or non-blood-related.[71] In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced a distinct classification for myeloid proliferation in individuals with Down syndrome.[72]

Blood cancers

[edit]Leukemia is 10 to 15 times more common in children with Down syndrome.[29] In particular, acute lymphoblastic leukemia is 20 times more common and the megakaryoblastic form of acute myeloid leukemia (acute megakaryoblastic leukemia), is 500 times more common.[73] Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL) is a leukemia of megakaryoblasts, the precursors cells to megakaryocytes which form blood platelets.[73] Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Down syndrome accounts for 1–3% of all childhood cases of ALL. It occurs most often in those older than nine years or having a white blood cell count greater than 50,000 per microliter and is rare in those younger than one year old. ALL in Down syndrome tends to have poorer outcomes than other cases of ALL in people without Down syndrome.[73][74] In short, the likelihood of developing acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is higher in children with Down syndrome compared to those without Down syndrome.[75]

Myeloid leukemia typically precedes Down syndrome and is accompanied by a condition known as transient abnormal myelopoiesis (TAM), which generally disrupts the differentiation of megakaryocytes and erythrocytes.[76] In Down syndrome, AMKL is typically preceded by transient myeloproliferative disease (TMD), a disorder of blood cell production in which non-cancerous megakaryoblasts with a mutation in the GATA1 gene rapidly divide during the later period of pregnancy.[73][77] GATA1 mutations combined with trisomy 21 contribute to a predisposition to TAM.[78] In trisomy 21, the process of leukemogenesis starts in early fetal life, with genetic factors, including GATA1 mutations, contributing to the development of TAM on the preleukemic pathway.[76] The condition affects 3–10% of babies with Down.[73] While it often spontaneously resolves within three months of birth, it can cause serious blood, liver, or other complications.[79] In about 10% of cases, TMD progresses to AMKL during the three months to five years following its resolution.[73][79][78]

Non-blood cancers

[edit]People with Down syndrome have a lower risk of all major solid cancers, including those of lung, breast, and cervix, with the lowest relative rates occurring in those aged 50 years or older.[71] This low risk is thought to be due to an increase in the expression of tumor suppressor genes present on chromosome 21.[80][71] One exception is testicular germ cell cancer which occurs at a higher rate in Down syndrome.[71]

Endocrine

[edit]Problems of the thyroid gland occur in 20–50% of individuals with Down syndrome.[9][29] Low thyroid is the most common form, occurring in almost half of all individuals.[9] Thyroid problems can be due to a poorly or nonfunctioning thyroid at birth (known as congenital hypothyroidism) which occurs in 1%[10] or can develop later due to an attack on the thyroid by the immune system resulting in Graves' disease or autoimmune hypothyroidism.[81] Type 1 diabetes mellitus is also more common.[9]

Gastrointestinal

[edit]Constipation occurs in nearly half of people with Down syndrome and may result in changes in behavior.[29] One potential cause is Hirschsprung's disease, occurring in 2–15%, which is due to a lack of nerve cells controlling the colon.[82] Other congenital problems can include duodenal atresia, imperforate anus and gastroesophageal reflux disease.[66] Celiac disease affects about 7–20%.[9][29]

Teeth

[edit]People with Down syndrome tend to be more susceptible to gingivitis as well as early, severe periodontal disease, necrotising ulcerative gingivitis, and early tooth loss, especially in the lower front teeth.[83][84] While plaque and poor oral hygiene are contributing factors, the severity of these periodontal diseases cannot be explained solely by external factors.[84] Research suggests that the severity is likely a result of a weakened immune system.[84][85] The weakened immune system also contributes to increased incidence of yeast infections in the mouth (from Candida albicans).[85]

People with Down syndrome also tend to have a more alkaline saliva resulting in a greater resistance to tooth decay, despite decreased quantities of saliva,[86] less effective oral hygiene habits, and higher plaque indexes.[83][85][86][87]

Higher rates of tooth wear and bruxism are also common.[85] Other common oral manifestations of Down syndrome include enlarged hypotonic tongue, crusted and hypotonic lips, mouth breathing, narrow palate with crowded teeth, class III malocclusion with an underdeveloped maxilla and posterior crossbite, delayed exfoliation of baby teeth and delayed eruption of adult teeth, shorter roots on teeth, and often missing and malformed (usually smaller) teeth.[83][85][86][87] Less common manifestations include cleft lip and palate and enamel hypocalcification (20% prevalence).[87]

Taurodontism, an elongation of the pulp chamber, has a high prevalence in people with DS.[88][89]

Fertility

[edit]Males with Down syndrome usually do not father children, while females have lower rates of fertility relative to those who are unaffected.[90] Fertility is estimated to be present in 30–50% of females.[91] Menopause usually occurs at an earlier age.[9] The poor fertility in males is thought to be due to problems with sperm development; however, it may also be related to not being sexually active.[90] As of 2006, three instances of males with Down syndrome fathering children and 26 cases of females having children have been reported.[90] Without assisted reproductive technologies, around half of the children of someone with Down syndrome will also have the syndrome.[90][92]

Cause

[edit]The cause of the extra full or partial chromosome is still unknown.[93] Most of the time, Down syndrome is caused by a random mistake in cell division during early development of the fetus, but not inherited,[94] and there is no scientific research which shows that environmental factors or the parents' activities contribute to Down syndrome. The only factor that has been linked to the increased chance of having a baby with Down syndrome is advanced parental age. This is mostly associated with advanced maternal age but about 10 per cent of cases are associated with advanced paternal age.[95]

Down syndrome is caused by having three copies of the genes on chromosome 21, rather than the usual two.[3][96] The parents of the affected individual are typically genetically normal.[14] Those who have one child with Down syndrome have about a 1% possibility of having a second child with the syndrome, if both parents are found to have normal karyotypes.[91]

The extra chromosome content can arise through several different ways. The most common cause (about 92–95% of cases) is a complete extra copy of chromosome 21, resulting in trisomy 21.[92][97] In 1–2.5% of cases, some of the cells in the body are normal and others have trisomy 21, known as mosaic Down syndrome.[91][98] The other common mechanisms that can give rise to Down syndrome include: a Robertsonian translocation, isochromosome, or ring chromosome. These contain additional material from chromosome 21 and occur in about 2.5% of cases.[29][91] An isochromosome results when the two long arms of a chromosome separate together rather than the long and short arm separating together during egg or sperm development.[92]

Trisomy 21

[edit]Down syndrome (also known by the karyotype 47,XX,+21 for females and 47,XY,+21 for males)[99] is mostly caused by a failure of the 21st chromosome to separate during egg or sperm development, known as nondisjunction.[92] As a result, a sperm or egg cell is produced with an extra copy of chromosome 21; this cell thus has 24 chromosomes. When combined with a normal cell from the other parent, the baby has 47 chromosomes, with three copies of chromosome 21.[3][92] About 88% of cases of trisomy 21 result from nonseparation of the chromosomes in the mother, 8% from nonseparation in the father, and 3% after the egg and sperm have merged.[100]

Mosaic Down syndrome

[edit]Mosaic Down syndrome is diagnosed when there is a mixture of two types of cells: some cells have three copies of chromosome 21 but some cells have the typical two copies of chromosome 21.[18] This type is the least common form of Down syndrome and accounts for only about 1% of all cases.[93] Children with mosaic Down syndrome may have the same features as other children with Down syndrome. However, they may have fewer characteristics of the condition due to the presence of some (or many) cells with a typical number of chromosomes.[18]

Translocation Down syndrome

[edit]The extra chromosome 21 material may also occur due to a Robertsonian translocation in 2–4% of cases.[91][101] In this translocation Down syndrome, the long arm of chromosome 21 is attached to another chromosome, often chromosome 14.[102] In a male affected with Down syndrome, it results in a karyotype of 46XY,t(14q21q).[102][103] This may be a new mutation or previously present in one of the parents.[104] The parent with such a translocation is usually normal physically and mentally;[102] however, during production of egg or sperm cells, a higher chance of creating reproductive cells with extra chromosome 21 material exists.[101] This results in a 15% chance of having a child with Down syndrome when the mother is affected and a less than 5% probability if the father is affected.[104] The probability of this type of Down syndrome is not related to the mother's age.[102] Some children without Down syndrome may inherit the translocation and have a higher probability of having children of their own with Down syndrome.[102] In this case it is sometimes known as familial Down syndrome.[105]

Mechanism

[edit]The extra genetic material present in Down syndrome results in overexpression of a portion of the 310 genes located on chromosome 21.[96] This overexpression has been estimated at 50%, due to the third copy of the chromosome present.[91] Some research has suggested the Down syndrome critical region is located at bands 21q22.1–q22.3,[106] with this area including genes for the amyloid precursor protein, superoxide dismutase, and likely the ETS2 proto oncogene.[107] Other research, however, has not confirmed these findings.[96] MicroRNAs are also proposed to be involved.[108]

The dementia that occurs in Down syndrome is due to an excess of amyloid beta peptide produced in the brain and is similar to Alzheimer's disease, which also involves amyloid beta build-up.[109] Amyloid beta is processed from amyloid precursor protein, the gene for which is located on chromosome 21.[109] Senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are present in nearly all by 35 years of age, though dementia may not be present.[14] It is hypothesized that those with Down syndrome lack a normal number of lymphocytes and produce less antibodies which is said to present an increased risk of infection.[29]

Epigenetics

[edit]Down syndrome is associated with an increased risk of some chronic diseases that are typically associated with older age such as Alzheimer's disease. It is believed that accelerated aging occurs and increases the biological age of tissues, but molecular evidence for this hypothesis is sparse. According to a biomarker of tissue age known as epigenetic clock, it is hypothesized that trisomy 21 increases the age of blood and brain tissue (on average by 6.6 years).[110]

Diagnosis

[edit]Screening before birth

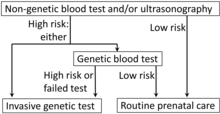

[edit]Guidelines recommend screening for Down syndrome to be offered to all pregnant women, regardless of age.[111][112] A number of tests are used, with varying levels of accuracy. They are typically used in combination to increase the detection rate.[29] None can be definitive; thus, if screening predicts a high possibility of Down syndrome, either amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling is required to confirm the diagnosis.[111]

Ultrasound

[edit]Prenatal ultrasound can be used to screen for Down syndrome. Findings that indicate increased chances when seen at 14 to 24 weeks of gestation include a small or no nasal bone, large ventricles, nuchal fold thickness, and an abnormal right subclavian artery, among others.[113] The presence or absence of many markers is more accurate.[113] Increased fetal nuchal translucency (NT) indicates an increased possibility of Down syndrome picking up 75–80% of cases and being falsely positive in 6%.[114]

-

Ultrasound of fetus with Down syndrome showing a large bladder

-

Enlarged NT and absent nasal bone in a fetus at 11 weeks with Down syndrome

Blood tests

[edit]Several blood markers can be measured to predict the chances of Down syndrome during the first or second trimester.[115][116] Testing in both trimesters is sometimes recommended and test results are often combined with ultrasound results.[115] In the second trimester, often two or three tests are used in combination with two or three of: α-fetoprotein, unconjugated estriol, total hCG, and free βhCG detecting about 60–70% of cases.[116]

Testing of the mother's blood for fetal DNA is being studied and appears promising in the first trimester.[117][118] The International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis considers it a reasonable screening option for those women whose pregnancies are at a high likelihood of trisomy 21.[119] Accuracy has been reported at 98.6% in the first trimester of pregnancy.[29] Confirmatory testing by invasive techniques (amniocentesis, CVS) is still required to confirm the screening result.[119]

Combinations

[edit]| Screen | Week of pregnancy when performed | Detection rate | False positive | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined test | 10–13.5 wks | 82–87% | 5% | Uses ultrasound to measure nuchal translucency in addition to blood tests for free or total beta-hCG and PAPP-A |

| Quad screen | 15–20 wks | 81% | 5% | Measures the maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein, unconjugated estriol, hCG, and inhibin-A |

| Integrated test | 15–20 wks | 94–96% | 5% | Is a combination of the quad screen, PAPP-A, and NT |

| Cell-free fetal DNA | From 10 wks[120] | 96–100%[117] | 0.3%[121] | A blood sample is taken from the mother by venipuncture and is sent for DNA analysis. |

Efficacy

[edit]For combinations of ultrasonography and non-genetic blood tests, screening in both the first and second trimesters is better than just screening in the first trimester.[111] Common screening techniques in use are able to pick up 90–95% of cases, with a false-positive rate of 2–5%.[115] If Down syndrome occurs in one in 500 pregnancies with a 90% detection rate and the test used has a 5% false-positive rate, of 28 women who test positive on screening, only one will have a fetus with Down syndrome confirmed. If the screening test has a 2% false-positive rate, this means of 11 women who test positive on screening, only one will have a fetus with Down syndrome.[115]

Invasive genetic testing

[edit]Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling are more reliable tests, but they increase the risk of miscarriage by between 0.5–1%.[122] The risk of limb problems may be increased in the offspring if chorionic villus sampling is performed before 10 weeks.[122]

The risk from the procedure is greater the earlier it is performed, thus amniocentesis is not recommended before 15 weeks gestational age and chorionic villus sampling before 10 weeks gestational age.[122]

Abortion rates

[edit]About 92% of pregnancies in Europe with a diagnosis of Down syndrome are terminated.[22] As a result, there is almost no one with Down syndrome in Iceland and Denmark, where screening is commonplace.[124] In the United States, the termination rate after diagnosis is around 75%,[124] but varies from 61 to 93%, depending on the population surveyed.[21] Rates are lower among women who are younger and have decreased over time.[21] When asked if they would have a termination if their fetus tested positive, 23–33% said yes, when high-risk pregnant women were asked, 46–86% said yes, and when women who screened positive are asked, 89–97% say yes.[125]

After birth

[edit]A diagnosis can often be suspected based on the child's physical appearance at birth.[10] An analysis of the child's chromosomes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, and to determine if a translocation is present, as this may help determine the chances of the child's parents having further children with Down syndrome.[10]

Management

[edit]Efforts such as early childhood intervention, therapies, screening for common medical issues, a good family environment, and work-related training can improve the development of children with Down syndrome and provide good quality of life. Common therapies utilized include physical therapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy.[126] Education and proper care can provide a positive quality of life.[7] Typical childhood vaccinations are recommended.[29]

Health screening

[edit]| Testing | Children[127] | Adults[9] |

|---|---|---|

| Hearing | 6 months, 12 months, then yearly | 3–5 years |

| T4 and TSH | 6 months, then yearly | |

| Eyes | 6 months, then yearly | 3–5 years |

| Teeth | 2 years, then every 6 months | |

| Celiac disease | Between 2 and 3 years of age, or earlier if symptoms occur |

|

| Sleep study | 3 to 4 years, or earlier if symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea occur |

|

| Neck X-rays | Between 3 and 5 years of age |

A number of health organizations have issued recommendations for screening those with Down syndrome for particular diseases.[127] This is recommended to be done systematically.[29]

At birth, all children should get an electrocardiogram and ultrasound of the heart.[29] Surgical repair of heart problems may be required as early as three months of age.[29] Heart valve problems may occur in young adults, and further ultrasound evaluation may be needed in adolescents and in early adulthood.[29] Due to the elevated risk of testicular cancer, some recommend checking the person's testicles yearly.[9]

Cognitive development

[edit]Some people with Down syndrome experience hearing loss. In this instance, hearing aids or other amplification devices can be useful for language learning.[29] Speech therapy may be useful and is recommended to be started around nine months of age.[29] As those with Down syndrome typically have good hand-eye coordination, learning sign language is a helpful communication tool.[47] Augmentative and alternative communication methods, such as pointing, body language, objects, or pictures, are often used to help with communication.[128] Behavioral issues and mental illness are typically managed with counseling or medications.[10]

Education programs before reaching school age may be useful.[1] School-age children with Down syndrome may benefit from inclusive education (whereby students of differing abilities are placed in classes with their peers of the same age), provided some adjustments are made to the curriculum.[129] In the United States, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1975 requires public schools generally to allow attendance by students with Down syndrome.[130]

Individuals with Down syndrome may learn better visually. Drawing may help with language, speech, and reading skills. Children with Down syndrome still often have difficulty with sentence structure and grammar, as well as developing the ability to speak clearly.[131] Several types of early intervention can help with cognitive development. Efforts to develop motor skills include physical therapy, speech and language therapy, and occupational therapy. Physical therapy focuses specifically on motor development and teaching children to interact with their environment. Speech and language therapy can help prepare for later language. Lastly, occupational therapy can help with skills needed for later independence.[132]

Other

[edit]Tympanostomy tubes are often needed[29] and often more than one set during the person's childhood.[64] Tonsillectomy is also often done to help with sleep apnea and throat infections.[29] Surgery does not correct every instance of sleep apnea and a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine may be useful in those cases.[64]

Efforts to prevent respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection with human monoclonal antibodies should be considered, especially in those with heart problems.[1] In those who develop dementia there is no evidence for memantine,[133] donepezil,[134] rivastigmine,[135] or galantamine.[136]

Prognosis

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with US and Sweden and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (January 2025) |

Between 5–15% of children with Down syndrome in Sweden attend regular school.[137] Some graduate from high school; however, most do not.[24] Of those with intellectual disability in the United States who attended high school about 40% graduated.[138] Many learn to read and write and some are able to do paid work.[24] In adulthood about 20% in the United States do paid work in some capacity.[25][139] In Sweden, however, less than 1% have regular jobs.[137] Many are able to live semi-independently,[14] but they often require help with financial, medical, and legal matters.[10] Those with mosaic Down syndrome usually have better outcomes.[91]

Individuals with Down syndrome have a higher risk of early death than the general population.[29] This is most often from heart problems or infections.[1][9] Following improved medical care, particularly for heart and gastrointestinal problems, the life expectancy has increased.[1] This increase has been from 12 years in 1912,[140] to 25 years in the 1980s,[1] to 50 to 60 years in the developed world in the 2000s.[9][10] Data collected between the 1985–2003 showed between 4–12% infants with Down syndrome die in the first year of life.[79] The probability of long-term survival is partly determined by the presence of heart problems. From research at the turn of the century, it tracked those with congenital heart problems, showing 60% survived to at least 10 years and 50% survived to at least 30 years of age. The research failed to track further aging beyond 30 years.[14] In those without heart problems, 85% studied survived to at least 10 years and 80% survived to at least 30 years of age.[14] It is estimated that 10% lived to 70 years of age in the early 2000s.[92] Much of this data is outdated and life expectancy has drastically improved with more equitable healthcare and continuous advancement of surgical practice.[141] The National Down Syndrome Society provides information regarding raising a child with Down syndrome.[142]

Epidemiology

[edit]

Down syndrome is the most common chromosomal abnormality in humans.[9] Globally, as of 2010[update], Down syndrome occurs in about 1 per 1,000 births[1] and results in about 17,000 deaths.[143] More children are born with Down syndrome in countries where abortion is not allowed and in countries where pregnancy more commonly occurs at a later age.[1] About 1.4 per 1,000 live births in the United States[144] and 1.1 per 1,000 live births in Norway are affected.[9] In the 1950s, in the United States, it occurred in 2 per 1,000 live births with the decrease since then due to prenatal screening and abortions.[104] The number of pregnancies with Down syndrome is more than two times greater with many spontaneously aborting.[10] It is the cause of 8% of all congenital disorders.[1]

Maternal age affects the chances of having a pregnancy with Down syndrome.[4] At age 20, the chance is 1 in 1,441; at age 30, it is 1 in 959; at age 40, it is 1 in 84; and at age 50 it is 1 in 44.[4] Although the probability increases with maternal age, 70% of children with Down syndrome are born to women 35 years of age and younger, because younger people have more children.[4] The father's older age is also a risk factor in women older than 35, but not in women younger than 35, and may partly explain the increase in risk as women age.[145]

History

[edit]

English physician John Langdon Down first described Down syndrome in 1862, recognizing it as a distinct type of mental disability, and again in a more widely published report in 1866.[29][147][148] Édouard Séguin described it as separate from cretinism in 1844.[30][149] By the 20th century, Down syndrome had become the most recognizable form of mental disability.

Due to his perception that children with Down syndrome shared facial similarities with those of Blumenbach's Mongoloid race, John Langdon Down used the term "mongoloid".[150] He felt that the existence of Down syndrome confirmed that all peoples were genetically related.[151] In the 1950s with discovery of the underlying cause as being related to chromosomes, concerns about the race-based nature of the name increased.[152]

In 1961, a group of nineteen scientists suggested that "mongolism" had "misleading connotations" and had become "an embarrassing term".[153] The World Health Organization (WHO) dropped the term in 1965 after a request by the delegation from the Mongolian People's Republic.[154] While this terminology continued to be used until the late twentieth century,[155]: 21 it is now considered unacceptable and is no longer in common use.

In antiquity, many infants with disabilities were either killed or abandoned.[30] In June 2020, the earliest incidence of Down syndrome was found in genomic evidence from an infant that was buried before 3200 BC at Poulnabrone dolmen in Ireland.[156] Researchers believe that a number of historical pieces of art portray Down syndrome, including pottery from the pre-Columbian Tumaco-La Tolita culture in present-day Colombia and Ecuador,[157] and the 16th-century painting The Adoration of the Christ Child.[158][159]

In the 20th century, many individuals with Down syndrome were institutionalized, few of the associated medical problems were treated, and most people died in infancy or early adulthood. With the rise of the eugenics movement, 33 of the then 48 U.S. states and several countries began programs of forced sterilization of individuals with Down syndrome and comparable degrees of disability. Action T4 in Nazi Germany saw the systematic murder of people with Down syndrome made public policy.[160]

With the discovery of karyotype techniques in the 1950s it became possible to identify abnormalities of chromosomal number or shape.[149] In 1959 Jérôme Lejeune reported the discovery that Down syndrome resulted from an extra chromosome.[29] However, Lejeune's claim to the discovery has been disputed,[161] and in 2014 the Scientific Council of the French Federation of Human Genetics unanimously awarded its Grand Prize to his colleague Marthe Gautier for her role in this discovery.[162] The discovery took place in the laboratory of Raymond Turpin at the Hôpital Trousseau in Paris, France.[163] Jérôme Lejeune and Marthe Gautier were both his students.[164]

As a result of this discovery, the condition became known as trisomy 21.[165] Even before the discovery of its cause, the presence of the syndrome in all races, its association with older maternal age, and its rarity of recurrence had been noticed. Medical texts had assumed it was caused by a combination of inheritable factors that had not been identified. Other theories had focused on injuries sustained during birth.[166]

Society and culture

[edit]Name

[edit]Down syndrome is named after John Langdon Down. He was the first person to provide an accurate description of the syndrome. His research that was published in 1866 earned him the recognition as the Father of the syndrome.[167] While others had previously recognized components of the condition, John Langdon Down described the syndrome as a distinct, unique medical condition.[19]

In 1975, the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) convened a conference to standardize the naming and recommended replacing the possessive form, "Down's syndrome", with "Down syndrome".[168] However, both the possessive and nonpossessive forms remain in use by the general population.[12] The term "trisomy 21" is also commonly used.[153][169]

Ethics

[edit]Obstetricians routinely offer antenatal screenings for various conditions, including Down syndrome.[170][171] When results from testing become available, it is considered an ethical requirement to share the results with the patient.[170][172]

Some bioethicists deem it reasonable for parents to select a child who would have the highest well-being.[173] One criticism of this reasoning is that it often values those with disabilities less.[174] Some parents argue that Down syndrome should not be prevented or cured and that eliminating Down syndrome amounts to genocide.[175][176] The disability rights movement does not have a position on screening,[177] although some members consider testing and abortion discriminatory.[177] Some in the United States who are anti-abortion support abortion if the fetus is disabled, while others do not.[178] Of a group of 40 mothers in the United States who have had one child with Down syndrome, half agreed to screening in the next pregnancy.[178]

Within the US, some Protestant denominations see abortion as acceptable when a fetus has Down syndrome while Orthodox Christianity and Roman Catholicism do not.[179] Women may face disapproval whether they choose abortion or not.[180] Some of those against screening refer to it as a form of eugenics.[179]

Advocacy groups

[edit]Advocacy groups for individuals with Down syndrome began to be formed after the Second World War.[181] These were organizations advocating for the inclusion of people with Down syndrome into the general school system and for a greater understanding of the condition among the general population,[181] as well as groups providing support for families with children living with Down syndrome.[181] Before this individuals with Down syndrome were often placed in mental hospitals or asylums. Organizations included the Royal Society for Handicapped Children and Adults founded in the UK in 1946 by Judy Fryd,[181][182] Kobato Kai founded in Japan in 1964,[181] the National Down Syndrome Congress founded in the United States in 1973 by Kathryn McGee and others,[181][183] and the National Down Syndrome Society founded in 1979 in the United States.[181] The first Roman Catholic order of nuns for women with Down Syndrome, Little Sisters Disciples of the Lamb, was founded in 1985 in France.[184]

The first World Down Syndrome Day was held on 21 March 2006.[185] The day and month were chosen to correspond with 21 and trisomy, respectively.[186] It was recognized by the United Nations General Assembly in 2011.[185]

Special21.org, founded in 2015, advocates the need for a specific classification category to enable Down syndrome swimmers the opportunity to qualify and compete at the Paralympic Games.[187] The project began when International Down syndrome swimmer Filipe Santos broke the world record in the 50m butterfly event, but was unable to compete at the Paralympic Games.[188][189]

Paralympic Swimming

[edit]International Paralympic Committee Para-swimming classification codes are based upon single impairment only, whereas Down syndrome individuals have both physical and intellectual impairments.

Although Down syndrome swimmers are able to compete in the Paralympic Swimming S14 intellectual impairment category (provided they score low in IQ tests), they are often outmatched by the superior physicality of their opponents.[190][191]

At present there is no designated Paralympic category for swimmers with Down syndrome, meaning they have to compete as intellectually disadvantaged athletes. This disregards their physical disabilities.[192][193]

A number of advocacy groups globally have been lobbying for the inclusion of a distinct classification category for Down syndrome swimmers within the IPC Classification Codes framework.[194]

Despite ongoing advocacy, the issue remains unresolved, and swimmers with Down syndrome continue to face challenges in accessing appropriate classification pathways.[195][196]

Research

[edit]Efforts are underway to determine how the extra chromosome 21 material causes Down syndrome, as currently this is unknown,[197] and to develop treatments to improve intelligence in those with the syndrome.[198] Two efforts being studied are the use stem cells[197] and gene therapy.[199][200] Other methods being studied include the use of antioxidants, gamma secretase inhibition, adrenergic agonists, and memantine.[201] Research is often carried out on an animal model, the Ts65Dn mouse.[202]

Other hominids

[edit]Down syndrome may also occur in hominids other than humans. In great apes chromosome 22 corresponds to the human chromosome 21[a] and thus trisomy 22 causes Down syndrome in apes. The condition was observed in a common chimpanzee in 1969 and a Bornean orangutan in 1979, but neither lived very long. The common chimpanzee Kanako (born around 1993, in Japan) has become the longest-lived known example of this condition. Kanako has some of the same symptoms that are common in human Down syndrome. It is unknown how common this condition is in chimps, but it is plausible it could be roughly as common as Down syndrome is in humans.[204][205]

Fossilized remains of a Neanderthal aged approximately 6 at death were described in 2024. The child, nicknamed Tina, suffered from a malformation of the inner ear that only occurs in people with Down syndrome, and would have caused hearing loss and disabling vertigo. The fact that a Neanderthal with such a condition survived to such an age was taken as evidence of compassion and extra-maternal care among Neanderthals.[206][207]

In popular culture

[edit]

Individuals

[edit]- Jamie Brewer is an American actress and model. She is best known for her roles in the FX horror anthology television series American Horror Story.[208] In its first season, Murder House, she portrayed Adelaide "Addie" Langdon; in the third season, Coven, she portrayed Nan, an enigmatic and clairvoyant witch; in the fourth season Freak Show, she portrayed Chester Creb's vision of his doll, Marjorie; in the seventh season Cult, she portrayed Hedda, a member of the 'SCUM' crew, led by feminist Valerie Solanas; and she also returned to her role as Nan in the eighth season, Apocalypse. In February 2015, Brewer became the first woman with Down syndrome to walk the red carpet at New York Fashion Week, for designer Carrie Hammer.[209]

- Sofía Jirau is a Puerto Rican model with Down syndrome, working with top designers and renowned media outlets such Vogue Mexico, People, Hola!, among others.[210][211][212] In February 2020, Jirau made her debut at New York Fashion Week.[213] Then in February 2022, she became the first-ever model with Down Syndrome to be hired by the American retail company Victoria's Secret.[214] She walked the LA Fashion Week runway in 2022.[215] Jirau launched a campaign in 2021 called Sin Límites or No Limits "which seeks to make visible the challenges facing the Down syndrome community, demonstrate our ability to achieve our goals, and raise awareness about the condition throughout the world."[215]

- Chris Nikic is the first person with Down syndrome to finish an Ironman Triathlon.[216] He was awarded the Jimmy V Award for Perseverance at the 2021 ESPY Awards.[217] Nikic continues to run races around the world, using his platform to promote his 1% Better message and bring awareness to the endless possibilities for people with Down syndrome.[218]

- Grace Strobel is an American model and the first person with Down Syndrome to represent an American skin-care brand.[219] She first joined Obagi in 2020, and continues to be an Ambassador for the brand as of 2022.[220][221] She walked the runway representing Tommy Hilfiger for Runway of Dreams New York Fashion Week 2020 and Atlantic City Fashion Week.[222] Strobel has been featured in Forbes, on The Today Show, Good Morning America, by Rihanna's Fenty Beauty, Lady Gaga's Kindness Channel, and many more.[222][223] She is also a public speaker and gives a presentation called #TheGraceEffect about what it is like to live with Down syndrome.[224][223]

Television and film

[edit]- Life Goes On is an American drama television series that aired on ABC from September 12, 1989, to May 23, 1993.[225] The show centers on the Thatcher family living in suburban Chicago: Drew, his wife Libby, and their children Paige, Rebecca and Charles. Charles, called Corky on the show and portrayed by Chris Burke, was the first major character on a television series with Down syndrome.[226] Burke's revolutionary role conveyed a realistic portrayal of people with Down syndrome and changed the way audiences viewed people with disabilities.[227]

- Struck by Lightning, an Australian film by Jerzy Domaradzki and starring Garry McDonald, is a comedy-drama depicting the efforts by a newly appointed physical education teacher to introduce soccer to a specialized school for youths with Down syndrome.

- Champions (2023) is a film starring four main actors with Down syndrome: Madison Tevlin, Kevin Iannucci, Matthew Von Der Ahe and James Day Keith.[228] It is an American sports comedy film directed by Bobby Farrelly in his solo directorial debut, from a screenplay written by Mark Rizzo. The film stars Woody Harrelson as a temperamental minor-league basketball coach who after an arrest must coach a team of players with intellectual disabilities as community service; Kaitlin Olson, Ernie Hudson, and Cheech Marin also star.

- Born This Way is an American reality television series produced by Bunim/Murray Productions featuring seven adults with Down syndrome with work hard to achieve goals and overcome obstacles.[229] The show received a Television Academy Honor in 2016.[230]

- The Peanut Butter Falcon is a 2019 American comedy-drama film written and directed by Tyler Nilson and Michael Schwartz, in their directorial film debut, and starring Zack Gottsagen, Shia LaBeouf, Dakota Johnson and John Hawkes.[231] The plot follows a young man with Down syndrome who escapes from an assisted living facility, in order to follow his dream of being a wrestler, and befriends a wayward fisherman on the run. As the two men form a rapid bond, a social worker attempts to track them.[232]

Music

[edit]- The Devo song "Mongoloid" is about someone with Down syndrome.

- The Amateur Transplants song "Your Baby" is about a fetus with Down syndrome.

Toys

[edit]- In 2023, Mattel released a Barbie doll with characteristics of a person having Down syndrome as a way to promote diversity.[233]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Using the traditional numbering; the current numbering scheme retains human chromosome numbers, using 2A and 2B instead of 2 and 3 to refer to the two chromosomes that fused into chromosome 2 in humans.[203]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Weijerman ME, de Winter JP (December 2010). "Clinical practice. The care of children with Down syndrome". European Journal of Pediatrics. 169 (12): 1445–1452. doi:10.1007/s00431-010-1253-0. PMC 2962780. PMID 20632187.

- ^ a b "What causes Down syndrome?". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. U.S. National Institutes of Health. 2014-01-17. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Patterson D (July 2009). "Molecular genetic analysis of Down syndrome". Human Genetics. 126 (1): 195–214. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0696-8. ISSN 0340-6717. PMID 19526251. S2CID 10403507.

- ^ a b c d e f Morris JK, Mutton DE, Alberman E (2002). "Revised estimates of the maternal age specific live birth prevalence of Down's syndrome". Journal of Medical Screening. 9 (1): 2–6. doi:10.1136/jms.9.1.2. PMID 11943789.

- ^ "Down syndrome – Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ a b "How do health care providers diagnose Down syndrome?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2014-01-17. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Roizen NJ, Patterson D (April 2003). "Down's syndrome". Lancet (Review). 361 (9365): 1281–1289. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12987-X. PMID 12699967. S2CID 33257578.

- ^ a b c "Facts About Down Syndrome". National Association for Down Syndrome. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Malt EA, Dahl RC, Haugsand TM, Ulvestad IH, Emilsen NM, Hansen B, et al. (February 2013). "Health and disease in adults with Down syndrome". Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening. 133 (3): 290–294. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.12.0390. PMID 23381164.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Kliegma RM (2011). "Down Syndrome and Other Abnormalities of Chromosome Number". Nelson textbook of pediatrics (19th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. pp. Chapter 76.2. ISBN 978-1-4377-0755-7.

- ^ a b GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ a b Smith K (2011). The politics of Down syndrome. [New Alresford, Hampshire]: Zero. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-84694-613-4. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ "What are common symptoms of Down syndrome?". NIH Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 31 January 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Hammer GD (2010). "Pathophysiology of Selected Genetic Diseases". In McPhee SJ (ed.). Pathophysiology of disease: an introduction to clinical medicine (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. Chapter 2. ISBN 978-0-07-162167-0.

- ^ a b "The Genetics of Down's Syndrome". www.intellectualdisability.info. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- ^ "Facts About Down Syndrome". National Association for Down Syndrome. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- ^ "LSUHSC School of Medicine". www.medschool.lsuhsc.edu. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- ^ a b c d "Facts about Down Syndrome | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021-04-06. Retrieved 2023-03-31.

- ^ a b "About Down Syndrome | National Down Syndrome Society (NDSS)". ndss.org. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- ^ Seror V, L'Haridon O, Bussières L, Malan V, Fries N, Vekemans M, et al. (March 2019). "Women's Attitudes Toward Invasive and Noninvasive Testing When Facing a High Risk of Fetal Down Syndrome". JAMA Network Open. 2 (3): e191062. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1062. PMC 6450316. PMID 30924894.

- ^ a b c Natoli JL, Ackerman DL, McDermott S, Edwards JG (February 2012). "Prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome: a systematic review of termination rates (1995-2011)". Prenatal Diagnosis. 32 (2): 142–153. doi:10.1002/pd.2910. PMID 22418958.

- ^ a b Mansfield C, Hopfer S, Marteau TM (September 1999). "Termination rates after prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome, spina bifida, anencephaly, and Turner and Klinefelter syndromes: a systematic literature review. European Concerted Action: DADA (Decision-making After the Diagnosis of a fetal Abnormality)". Prenatal Diagnosis. 19 (9). Wiley: 808–812. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0223(199909)19:9<808::aid-pd637>3.0.co;2-b. PMID 10521836. S2CID 29637272.

- ^ "Down Syndrome: Other FAQs". 2014-01-17. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ a b c Steinbock B (2011). "The Risk of Transmitting Disease or Disability". Life before birth the moral and legal status of embryos and fetuses (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-19-971207-6. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ a b Szabo L (May 9, 2013). "Life with Down syndrome is full of possibilities". USA Today. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Martínez-Espinosa RM, Molina Vila MD, Reig García-Galbis M (June 2020). "Evidences from Clinical Trials in Down Syndrome: Diet, Exercise and Body Composition". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17 (12): 4294. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124294. PMC 7344556. PMID 32560141.

- ^ GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Hickey F, Hickey E, Summar KL (2012). "Medical update for children with Down syndrome for the pediatrician and family practitioner". Advances in Pediatrics. 59 (1). Elsevier BV: 137–157. doi:10.1016/j.yapd.2012.04.006. PMID 22789577.

- ^ a b c Evans-Martin FF (2009). Down syndrome. New York: Chelsea House. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4381-1950-2.

- ^ Faragher R, Clarke B, eds. (2013). "Introduction". Educating Learners with Down Syndrome: Research, theory, and practice with children and adolescents. Taylor & Francis. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-134-67335-3. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ Hippolyte L, Iglesias K, Van der Linden M, Barisnikov K (August 2010). "Social reasoning skills in adults with Down syndrome: the role of language, executive functions and socio-emotional behaviour". Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 54 (8): 714–726. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01299.x. PMID 20590998.

- ^ Johnston JM, Smyth MD, McKinstry RC (2008). "Basics of Neuroimaging in Pediatric Epilepsy". In Pellock JM, Bourgeois BF, Dodson WE, Nordli Jr DR, Sankar R (eds.). Pediatric epilepsy diagnosis and therapy (3rd ed.). New York: Demos Medical Pub. p. Chapter 67. ISBN 978-1-934559-86-4. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Epstein CJ (2007). The consequences of chromosome imbalance: principles, mechanisms, and models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 255–256. ISBN 978-0-521-03809-6. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ Marion RW, Samanich JN (2012). "Genetics". In Bernstein D, Shelov SP (eds.). Pediatrics for medical students (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-7817-7030-9. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ Bertoti DB, Smith DE (2008). "Mental Retardation: Focus on Down Syndrome". In Tecklin JS (ed.). Pediatric physical therapy (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-7817-5399-9. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ a b c Domino FJ, ed. (2007). The 5-minute clinical consult 2007 (2007 ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-7817-6334-9. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ Perkins JA (December 2009). "Overview of macroglossia and its treatment". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 17 (6): 460–465. doi:10.1097/moo.0b013e3283317f89. PMID 19713845. S2CID 45941755.

- ^ Wilson GN, Cooley WC (2006). Preventive management of children with congenital anomalies and syndromes (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-521-61734-5. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ Kumin L. Resource Guide to Oral Motor Skill Difficulties in Children with Down Syndrome (PDF). Loyola College of Maryland.

- ^ Bull MJ, Trotter T, Santoro SL, Christensen C, Grout RW, Burke LW, et al. (Council on Genetics) (May 2022). "Health Supervision for Children and Adolescents With Down Syndrome". Pediatrics. 149 (5). doi:10.1542/peds.2022-057010. PMID 35490285. S2CID 248252638.

- ^ a b Bull MJ (June 2020). "Down Syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (24): 2344–2352. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1706537. PMID 32521135. S2CID 219586275.

- ^ Williams Textbook of Endocrinology Expert Consult (12th ed.). London: Elsevier Health Sciences. 2011. ISBN 978-1-4377-3600-7. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ Pierce M, Ramsey K, Pinter J (2 April 2019). "Trends in Obesity and Overweight in Oregon Children With Down Syndrome". Global Pediatric Health. 6: 2333794X19835640. doi:10.1177/2333794X19835640. PMC 6446252. PMID 31044152.

- ^ "Early Development for Children with Down Syndrome". INHS Cambridgeshire Community Services NHS Trust. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Winders P, Wolter-Warmerdam K, Hickey F (April 2019). "A schedule of gross motor development for children with Down syndrome". Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 63 (4): 346–356. doi:10.1111/jir.12580. PMID 30575169. S2CID 58592265.

- ^ a b c d e Reilly C (October 2012). "Behavioural phenotypes and special educational needs: is aetiology important in the classroom?". Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 56 (10): 929–946. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01542.x. PMID 22471356.

- ^ Batshaw M, ed. (2005). Children with disabilities (5th ed.). Baltimore [u.a.]: Paul H. Brookes. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-55766-581-2. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ Patterson T, Rapsey CM, Glue P (April 2013). "Systematic review of cognitive development across childhood in Down syndrome: implications for treatment interventions". Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 57 (4): 306–318. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01536.x. PMID 23506141.

- ^ Windsperger K, Hoehl S (2021). "Development of Down Syndrome Research Over the Last Decades-What Healthcare and Education Professionals Need to Know". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 12: 749046. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.749046. PMC 8712441. PMID 34970162.

- ^ Kent RD, Vorperian HK (February 2013). "Speech impairment in Down syndrome: a review". Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 56 (1): 178–210. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2012/12-0148). PMC 3584188. PMID 23275397.

- ^ McGuire D, Chicoine B (2006). Mental Wellness in Adults with Down Syndrome. Bethesday, MD: Woodbine House, Inc. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-890627-65-2.

- ^ Margulies P (2007). Down syndrome (1st ed.). New York: Rosen Pub. Group. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4042-0695-3.

- ^ Schwartz MW, ed. (2012). The 5-minute pediatric consult (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-4511-1656-4. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ Santoro JD, Filipink RA, Baumer NT, Bulova PD, Handen BL (2023-03-01). "Down syndrome regression disorder: updates and therapeutic advances". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 36 (2): 96–103. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000845. ISSN 1473-6578. PMID 36705008.

- ^ Skoto BG, Roberts M (2024-02-28). "Down Syndrome". In Domino FJ (ed.). The 5-Minute Clinical Consult 2025. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-9752-3473-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Weijerman ME, de Winter JP (December 2010). "Clinical practice. The care of children with Down syndrome". European Journal of Pediatrics. 169 (12): 1445–1452. doi:10.1007/s00431-010-1253-0. PMC 2962780. PMID 20632187.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Trisomy 21/Down Syndrome - EyeWiki". eyewiki.org. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ a b Bull MJ, Trotter T, Santoro SL, Christensen C, Grout RW, THE COUNCIL ON GENETICS (2022-05-01). "Health Supervision for Children and Adolescents With Down Syndrome". Pediatrics. 149 (5). doi:10.1542/peds.2022-057010. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 35490285.

- ^ "Strabismus and Amblyopia | Boston Children's Hospital". www.childrenshospital.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ a b "Keratoconus - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ a b "Keratoconus". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 2021-08-08. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ Kliegma RM (2011). "Down Syndrome and Other Abnormalities of Chromosome Number". Nelson textbook of pediatrics (19th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. pp. Chapter 76.2. ISBN 978-1-4377-0755-7.

- ^ a b c Rodman R, Pine HS (June 2012). "The otolaryngologist's approach to the patient with Down syndrome". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 45 (3): 599–629, vii–viii. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2012.03.010. PMID 22588039.

- ^ Evans-Martin FF (2009). Down syndrome. New York: Chelsea House. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-4381-1950-2.

- ^ a b c Tintinalli JE (2010). "The Child with Special Health Care Needs". Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Emergency Medicine (Tintinalli)). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. pp. Chapter 138. ISBN 978-0-07-148480-0.

- ^ a b Goldstein S, ed. (2011). Handbook of neurodevelopmental and genetic disorders in children (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. p. 365. ISBN 978-1-60623-990-2. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ Prasher VP (2009). Neuropsychological assessments of dementia in Down syndrome and intellectual disabilities. London: Springer. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-84800-249-4. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ a b Bush D, Galambos C, Dunbar Ivy D (March 2021). "Pulmonary hypertension in children with Down syndrome". Pediatric Pulmonology. 56 (3): 621–629. doi:10.1002/ppul.24687. PMID 32049444. S2CID 211087826.

- ^ Urbano R (9 September 2010). Health Issues Among Persons With Down Syndrome. Academic Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-12-374477-7. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d Nixon DW (March 2018). "Down Syndrome, Obesity, Alzheimer's Disease, and Cancer: A Brief Review and Hypothesis". Brain Sciences. 8 (4): 53. doi:10.3390/brainsci8040053. PMC 5924389. PMID 29587359.

- ^ Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, et al. (July 2009). "The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes". Blood. 114 (5): 937–951. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. PMID 19357394.

- ^ a b c d e f Seewald L, Taub JW, Maloney KW, McCabe ER (September 2012). "Acute leukemias in children with Down syndrome". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 107 (1–2): 25–30. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.07.011. PMID 22867885.

- ^ Lee P, Bhansali R, Izraeli S, Hijiya N, Crispino JD (September 2016). "The biology, pathogenesis and clinical aspects of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children with Down syndrome". Leukemia. 30 (9): 1816–1823. doi:10.1038/leu.2016.164. PMC 5434972. PMID 27285583.

- ^ Li J, Kalev-Zylinska ML (2022). "Advances in molecular characterization of myeloid proliferations associated with Down syndrome". Frontiers in Genetics. 13: 891214. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.891214. PMC 9399805. PMID 36035173.

- ^ a b Gupte A, Al-Antary ET, Edwards H, Ravindranath Y, Ge Y, Taub JW (July 2022). "The paradox of Myeloid Leukemia associated with Down syndrome". Biochemical Pharmacology. 201: 115046. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115046. PMID 35483417. S2CID 248431139.

- ^ Tamblyn JA, Norton A, Spurgeon L, Donovan V, Bedford Russell A, Bonnici J, et al. (January 2016). "Prenatal therapy in transient abnormal myelopoiesis: a systematic review". Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 101 (1): F67 – F71. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2014-308004. PMID 25956670. S2CID 5958598.

- ^ a b Bhatnagar N, Nizery L, Tunstall O, Vyas P, Roberts I (October 2016). "Transient Abnormal Myelopoiesis and AML in Down Syndrome: an Update". Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports. 11 (5): 333–341. doi:10.1007/s11899-016-0338-x. PMC 5031718. PMID 27510823.

- ^ a b c Gamis AS, Smith FO (November 2012). "Transient myeloproliferative disorder in children with Down syndrome: clarity to this enigmatic disorder". British Journal of Haematology. 159 (3): 277–287. doi:10.1111/bjh.12041. PMID 22966823. S2CID 37593917.

- ^ Thomas-Tikhonenko A, ed. (2010). Cancer genome and tumor microenvironment (Online-Ausg. ed.). New York: Springer. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-4419-0711-0. Archived from the original on 2015-07-04.

- ^ Graber E, Chacko E, Regelmann MO, Costin G, Rapaport R (December 2012). "Down syndrome and thyroid function". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 41 (4): 735–745. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2012.08.008. PMID 23099267.

- ^ Moore SW (August 2008). "Down syndrome and the enteric nervous system". Pediatric Surgery International. 24 (8): 873–883. doi:10.1007/s00383-008-2188-7. PMID 18633623. S2CID 11890549.

- ^ a b c Cawson RA, Odell EW (2012). Cawson's essentials of oral pathology and oral medicine (8th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 419–421. ISBN 978-0443-10125-0.

- ^ a b c Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA, eds. (2006). Carranza's clinical periodontology (10th ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co. pp. 299, 397, 409, 623. ISBN 978-1-4160-2400-2.

- ^ a b c d e Avery DR, Dean JA, McDonald RE (2004). Dentistry for the child and adolescent (8th ed.). St. Louis, Mo: Mosby. pp. 164–168, 190–194, 474. ISBN 978-0-323-02450-1.

- ^ a b c Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP (2002). Contemporary oral and maxillofacial pathology (2nd ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-323-01723-7.

- ^ a b c Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RC (2008). Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic Correlations (5th ed.). St Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier. pp. 353–354. ISBN 978-1-4557-0262-6.

- ^ Bell J, Civil CR, Townsend GC, Brown RH (December 1989). "The prevalence of taurodontism in Down's syndrome". Journal of Mental Deficiency Research. 33 (6): 467–476. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.1989.tb01502.x. PMID 2533267.

- ^ Rajić Z, Mestrović SR (December 1998). "Taurodontism in Down's syndrome". Collegium Antropologicum. 22 (Suppl): 63–67. PMID 9951142.

- ^ a b c d Pradhan M, Dalal A, Khan F, Agrawal S (December 2006). "Fertility in men with Down syndrome: a case report". Fertility and Sterility. 86 (6): 1765.e1–1765.e3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.03.071. PMID 17094988. S2CID 32384231.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nelson MR (2011). Pediatrics. New York: Demos Medical. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-61705-004-6. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ a b c d e f Reisner H (2013). Essentials of Rubin's Pathology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 129–131. ISBN 978-1-4511-8132-6. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ a b "What is Down Syndrome? | National Down Syndrome Society". NDSS. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ "Down syndrome - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ Ramasamy R, Chiba K, Butler P, Lamb DJ (June 2015). "Male biological clock: a critical analysis of advanced paternal age". Fertility and Sterility. 103 (6): 1402–1406. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.03.011. PMC 4955707. PMID 25881878.

- ^ a b c Lana-Elola E, Watson-Scales SD, Fisher EM, Tybulewicz VL (September 2011). "Down syndrome: searching for the genetic culprits". Disease Models & Mechanisms. 4 (5): 586–595. doi:10.1242/dmm.008078. PMC 3180222. PMID 21878459.

- ^ "Birth Defects, Down Syndrome". National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. US: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013-11-06. Archived from the original on 2017-07-28.

- ^ Mandal K (2013). Treatment & prognosis in pediatrics. Jaypee Brothers Medical P. p. 391. ISBN 978-93-5090-428-2. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ Fletcher-Janzen E, Reynolds CR (2007). Encyclopedia of special education: a reference for the education of children, adolescents, and adults with disabilities and other exceptional individuals (3rd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 458. ISBN 978-0-470-17419-7. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ Zhang DY, Cheng L (2008). Molecular genetic pathology. Totowa, N.J.: Humana. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-59745-405-6. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ a b David AK (2013). Family Medicine Principles and Practice (Sixth ed.). New York, NY: Springer New York. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-387-21744-4. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ a b c d e Cummings M (2013). Human Heredity: Principles and Issues (10th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-285-52847-2. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ Strauss JF, Barbieri RL (2009). Yen and Jaffe's reproductive endocrinology: physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical management (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 791. ISBN 978-1-4160-4907-4. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ a b c Menkes JH, Sarnat HB (2005). Child neurology (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-7817-5104-9. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ Gardner RJ, Sutherland GR, Shaffer LG, eds. (2012). Chromosome abnormalities and genetic counseling (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-19-974915-7. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23.

- ^ "Genetics of Down syndrome". Archived from the original on 2011-05-27. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ Ebert MH, ed. (2008). "Psychiatric Genetics". Current diagnosis & treatment psychiatry (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. Chapter 3. ISBN 978-0-07-142292-5.

- ^ Patterson D, Cabelof DC (April 2012). "Down syndrome as a model of DNA polymerase beta haploinsufficiency and accelerated aging". Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 133 (4): 133–137. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2011.10.001. PMID 22019846. S2CID 3663890.

- ^ a b Weksler ME, Szabo P, Relkin NR, Reidenberg MM, Weksler BB, Coppus AM (April 2013). "Alzheimer's disease and Down's syndrome: treating two paths to dementia". Autoimmunity Reviews. 12 (6): 670–673. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2012.10.013. PMID 23201920.

- ^ Horvath S, Garagnani P, Bacalini MG, Pirazzini C, Salvioli S, Gentilini D, et al. (June 2015). "Accelerated epigenetic aging in Down syndrome". Aging Cell. 14 (3): 491–495. doi:10.1111/acel.12325. PMC 4406678. PMID 25678027.

- ^ a b c d ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins (January 2007). "ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 77: screening for fetal chromosomal abnormalities". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 109 (1): 217–227. doi:10.1097/00006250-200701000-00054. PMID 17197615.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2008). "CG62: Antenatal care". London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ a b Agathokleous M, Chaveeva P, Poon LC, Kosinski P, Nicolaides KH (March 2013). "Meta-analysis of second-trimester markers for trisomy 21". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 41 (3): 247–261. doi:10.1002/uog.12364. PMID 23208748.

- ^ Malone FD, D'Alton ME (November 2003). "First-trimester sonographic screening for Down syndrome". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 102 (5 Pt 1): 1066–1079. doi:10.1016/j.obstetgynecol.2003.08.004. PMID 14672489. S2CID 24592539.

- ^ a b c d Canick J (June 2012). "Prenatal screening for trisomy 21: recent advances and guidelines". Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 50 (6): 1003–1008. doi:10.1515/cclm.2011.671. PMID 21790505. S2CID 37417471.

- ^ a b Alldred SK, Deeks JJ, Guo B, Neilson JP, Alfirevic Z (June 2012). "Second trimester serum tests for Down's Syndrome screening" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (6): CD009925. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009925. PMC 7086392. PMID 22696388. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ a b Mersy E, Smits LJ, van Winden LA, de Die-Smulders CE, Paulussen AD, Macville MV, et al. (Jul–Aug 2013). "Noninvasive detection of fetal trisomy 21: systematic review and report of quality and outcomes of diagnostic accuracy studies performed between 1997 and 2012". Human Reproduction Update. 19 (4): 318–329. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt001. PMID 23396607.