Ebola virus epidemic in Guinea

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 19 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 19 min

A map of Guinea where the Ebola virus outbreak began | |

| Cases contracted in Guinea | 3,806 (as of 25 October 2015[update])[1] |

|---|---|

| Deaths | 2,535 |

An epidemic of Ebola virus disease in Guinea from 2013 to 2016 represented the first-ever outbreak of Ebola in a West African country. Previous outbreaks had been confined to several countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.[2]

The epidemic, which began with the death of a two-year-old boy, was part of a larger Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa which spread through Guinea and the neighboring countries of Liberia and Sierra Leone, with minor outbreaks occurring in Senegal, Nigeria, and Mali. In December 2015, Guinea was declared free of Ebola transmission by the U.N. World Health Organization,[3] however further cases continued to be reported from March 2016.[4] The country was again declared as Ebola-free in June 2016.[5]

Epidemiology

[edit]| Articles related to the |

| Western African Ebola virus epidemic |

|---|

|

| Overview |

| Nations with widespread cases |

| Other affected nations |

| Other outbreaks |

Researchers from the Robert Koch Institute believe that the index case was a one or two-year-old boy who lived in the remote village of Meliandou, Guéckédou located in the Nzérékoré Region of Guinea. Researchers believe that the boy was said to have contracted the virus while he was playing near a tree that was a roosting place for Angolan free-tailed bats infected with the virus.[6] Dr. Fabian Leendertz, an epidemiologist who was part of the investigative team, said Ebola virus is transmitted to humans either through contact with larger wildlife or by direct contact with bats. The boy, later identified as Emile Ouamouno, fell ill on 2 December 2013 and died four days later.[7][8][9] The boy's sister fell ill next, followed by his mother and grandmother.[10][11] It is believed the Ebola virus later spread to the villages of Dandou Pombo and Dawa, both in Guéckédou, by the midwife who attended the boy. From Dawa village the virus spread to Guéckédou Baladou District and Guéckédou Farako District, and on to Macenta and Kissidougou.[10][11]

Although Ebola represents a major public health issue in sub-Saharan Africa, no cases had ever been reported in West Africa and the early cases were diagnosed as other diseases more common to the area such as Lassa fever, another hemorrhagic fever similar to Ebola. Thus, it was not until March 2014 that the outbreak was recognized as Ebola. The Ministry of Health of Guinea notified the World Health Organization (WHO), and on 23 March the WHO announced an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Guinea with a total of 49 cases as of that date.[12][13][14][15] By late May, the outbreak had spread to Conakry, Guinea's capital, a city of about two million inhabitants.[16]

Containment efforts

[edit]Quarantines and travel restrictions

[edit]

In August, Guinea's President Alpha Conde declared a national health emergency due to the outbreak. He stated efforts to control the spread of the Ebola virus would include forbidding Ebola patients from leaving their homes, border control, travel restrictions, and hospitalization for individuals suspected to be infected until cleared by laboratory results. He also banned the transporting of the dead between towns.[17]

Good disease tracing was important to prevent the outbreak from spreading. Previous Ebola outbreaks had occurred in remote areas making containment easier; the West African outbreak struck in an area that lies at the centre of both a highly-mobile and densely populated region which made tracking more difficult: "This time, the virus is traveling effortlessly across borders by plane, car and foot, shifting from forests to cities and springing up in clusters far from any previously known infections. Border closures, flight bans and mass quarantines have been ineffective." Peter Piot, who co-discovered Ebola, said Ebola "isn't striking in a 'linear fashion' this time. It's hopping around, especially in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone".[18]

Fear of healthcare workers and clinics

[edit]

Containment was also difficult due to fear of healthcare workers. Infected people and those that they were in contact with evaded surveillance, moving at will and hiding their illnesses while they infected others in turn. Entire villages, stricken by fear, closed themselves off, giving the disease an opportunity to strike in another area. It was reported that in some areas it was believed that health workers were purposely spreading the disease to the people, while others believed that the disease did not exist. Riots broke out in the regional capital, Nzérékoré, when rumors were spread that people were being contaminated when health workers were spraying a market area to decontaminate it.[19]

In May, the number of Ebola cases appeared to be decreasing and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) closed a treatment facility in the Macenta region because the outbreak of Ebola there appeared to have been resolved. At the time it was thought that the new cases were caused by people returning from Liberia or from Sierra Leone; however it was later suggested that villagers had become fearful and were hiding cases rather than reporting them. Seeing workers wearing the required protection outfits worn by health workers and taking those suspected of having Ebola or of being contacts to the treatment center (perhaps never to be seen again), refusing the usual burial rituals when a patient died, and other actions taken by the unfamiliar individuals that had come to their remote areas, had led to rumors of organ harvesting and government and tribal plots. According to a September news report, "Many Guineans say local and foreign healthcare workers are part of a conspiracy which either deliberately introduced the outbreak, or invented it as a means of luring Africans to clinics to harvest their blood and organs."[20] As described in another news article, "The health workers don’t look like any people you’ve ever seen. They perform stiffly and slowly, and then they disappear into the tent where your mother or brother may be, and everything that happens inside is left to your imagination. Villagers began to whisper to one another—They’re harvesting our organs; they’re taking our limbs".[21] Moreover, due to fear, many people were avoiding hospital treatment for any ailment and were self-treating with over the counter drugs from a pharmacy.[20]

On 18 September, eight members of a health care team were murdered by local villagers in the town of Womey near Nzérékoré. The team consisted of Guinean health and government officials accompanied by journalists, who had been distributing Ebola information and doing disinfection work. They were attacked with machetes and clubs, and their bodies were found in a septic tank. The dead included three journalists and four volunteers.[22][23][24]

Outbreak progression

[edit]October 2014

[edit]

The governor of Conakry, Soriba Sorel Camara, prohibited all cultural events for the holiday of Tabaski in a decree of 2 October 2014.[25][26]

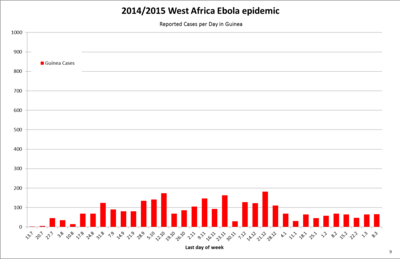

In the WHO Situation Report of 8 October, it was reported, that the transmission of Ebola was persistently high with approximately 100 new confirmed cases in the first week of October. The first cases were reported in the district of Lola.[27] Médecins Sans Frontières reported a massive spike in the number of new cases in the capital city of Conakry. One facility admitted 22 patients in a single day (6 October), 18 of them coming from Coyah region, 50 kilometres (31 miles) east of Conakry.[28]

On 19 October, Guinea reported two new districts with Ebola cases. The Kankan district, on the border with the Côte d'Ivoire and a major trade route to Mali, confirmed one case. Kankan also borders the district of Kerouane in this country, one of the areas with the most intense virus transmissions. The Faranah district to the north of the border area of Koinadugu in Sierra Leone also reported a confirmed case. Koinadugu was one of the last Ebola-free regions in that country. According to a WHO report, this new development highlights the need for increased surveillance of cross border traffic in an effort to contain the disease to the three most affected countries.[29]

On 23 October, Saccoba Keita, the head of Guinea's Ebola mission, announced the government has started compensating the families of health care workers who died after contracting the virus. At that time, 42 health care workers had died, including doctors, nurses, drivers, and porters. The compensation totals $10,000 (£6,200) and is to be paid as a lump sum.[30]

November 2014

[edit]In mid-November, the WHO reported that while intense transmission persists and cases and deaths continue to be under-reported, there is some evidence that case incidence is no longer increasing nationally in Guinea. They report that case numbers in some districts have been fluctuating, but they remain consistently high. New case numbers have been declining in the outbreak's point of origin, Gueckedou, but transmission continues to be high in Macenta. Of a total of 34 districts in Guinea, 10 remain unaffected by Ebola, contrasting with Liberia and Sierra Leone, where every district has been affected.[31]

On 20 November, the local Red Cross in Kankan Prefecture sent blood samples via a courier when the taxi he was traveling in was stopped by robbers. The bandits made off with the cooler bag containing the blood samples. The Guinea authorities made a public appeal for the return of the blood samples. The robbery occurred near the town of Kissidougou.[32]

December 2014

[edit]On 14 December the WHO stated that 17 districts reported new confirmed or suspected cases in this week. Guinea reported 2,416 cases with 1,525 deaths on this date. Only 10 out of the 34 districts have not reported cases. Conakry reported 18 new cases in this week. The northern district of Siguiri is of particular concern, as it borders Mali and reported 4 new probable cases.[33]

Free of Ebola transmission

[edit]The country was declared free of Ebola transmission on 29 December 2015, 42 days after the last Ebola patient tested negative for a second time.[34] Guinea was subsequently in a 90-day period of heightened surveillance according to the U.N. World Health Organization which also offered assistance[3] - with funding from the agency's donors.

New cases March 2016

[edit]On 17 March 2016, the government of Guinea reported 2 people had tested positive for Ebola virus in Korokpara.[4] It was also reported that they were from a village where members of one family had died recently from vomiting (and diarrhoea).[35] On 19 March, it was reported that another individual died due to the virus, at the treatment centre in Nzerekore.[36] The country's government quarantined an area around the home where the cases took place. This region of Guinea is where the first case was registered in December 2013, at the beginning of the Ebola outbreak.[37] On 22 March, it was reported that medical authorities in Guinea have quarantined 816 people as possibly having had contact with the prior cases (more than one hundred individuals were considered high risk[38]);[39] on the same day Liberia ordered its border with Guinea closed.[40] Macenta prefecture, 200 kilometers from Korokpara, registered the fifth fatality due to the Ebola virus disease in Guinea.[41] On 29 March it was reported that about 1000 contacts had been identified (142 as high risk),[42] and on 30 March 3 more confirmed cases were reported from the sub-prefecture of Koropara in Guinea.[43] On 1 April it was reported that possible contacts, which number in the hundreds, had been vaccinated with an experimental vaccine, in a "ring vaccination" approach.[44]

On 5 April it was reported that there were nine new cases of Ebola since the virus resurfaced. Of these nine cases eight have died.[45] After a 42-day waiting period, the WHO declared the country free of Ebola on 1 June.[5]

Vaccines

[edit]After a trial run of an experimental Ebola vaccine involving 11,000 people in Guinea, Merck, the vaccine's manufacturer, announced it was found to be “highly protective” against the virus.[46] This confirmed the results of a study published in 2015 that awarded the vaccine 100 percent effectiveness after tests on 4000 people in Guinea who had been in close contact with Ebola patients.[46] However, a study sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted by researchers from the U.S. National Academy of Medicine, called the vaccine's effectiveness in preventing Ebola infections into question.[47] In particular, the authors criticized the methodology of the patient trail, and argued that the protection provided by the vaccine may be lower than officially announced.[47]

The WHO approved the vaccine for use in the ongoing Ebola outbreak on 29 May 2017.[48][49]

It was announced in May 2017 that the Gamaleya Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology in Russia would deliver 1000 doses of an independently produced vaccine to Guinea for testing. According to a Xinhua report, it is the only officially authorized and approved Ebola vaccine for clinical use to date.[50]

Works derived from the Ebola crisis

[edit]- "White Ebola", a political song by Mr. Monrovia, AG Da Profit and Daddy Cool, centered on the general mistrust of foreigners.[51]

- "Ebola in Town", a dance tune by a group of West African rappers, D-12, Shadow and Kuzzy Of 2 Kings, warns people of the dangers of the Ebola virus and explaining how to react.[52][53]

- Senegalese rapper Xuman parodied Rihanna's "Umbrella" in "Ebola est là" (Ebola Is Here). The song's lyrics warn locals that, "The disease is among our neighbours, Liberians and Guineans."[53][54]

- "Africa Stop Ebola", featuring contributions from Malian, Guinean, Ivorian, Congolese and Senegalese artists was recorded to raise awareness of Ebola and offers info on how people can protect themselves from the disease.[55] The song is sung in several of the local languages.[56]

- There are a number of Ebola-themed jokes circulating in West Africa.[57]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Ebola Situation Report – 28 October 2015" (PDF). World Health Organisation. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ "Ebola virus disease Fact sheet No. 103". World Health Organization. September 2014.

- ^ a b no by-line.--> (29 December 2015). "UN declares end to Ebola virus transmission in Guinea; first time all three host countries free". UN News Center. United Nations. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ a b "Guinea says two people tested positive for Ebola". Reuters. 17 March 2016.

- ^ a b "End of Ebola transmission in Guinea". Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ von Csefalvay, Chris (2023), "Host-vector and multihost systems", Computational Modeling of Infectious Disease, Elsevier, pp. 121–149, doi:10.1016/b978-0-32-395389-4.00013-x, ISBN 978-0-323-95389-4, retrieved 2 March 2023

- ^ Sack, Kevin; Fink, Sheri; Belluck, Pam; Nossiter, Adam (29 December 2014). "How Ebola Roared Back". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Ebola: Patient zero was a toddler in Guinea - CNN.com". CNN. 28 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ "Ebola Patient Zero: Emile Ouamouno Of Guinea First To Contract Disease". International Business Times. 28 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ a b Baize, Sylvain; Pannetier, Delphine; Oestereich, Lisa; Rieger, Toni (16 April 2014). "Emergence of Zaire Ebola Virus Disease in Guinea — Preliminary Report". New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (15): 1418–25. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1404505. PMID 24738640. S2CID 34198809.

- ^ a b John Vidal (23 August 2014). "Ebola: research team says migrating fruit bats responsible for outbreak". the Guardian. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ "How Ebola sped out of control". Washington Post.

- ^ "Previous Updates: 2014 West Africa Outbreak". 17 July 2019.

- ^ "Guinea: Ebola epidemic declared". MSF UK. 24 March 2014.

- ^ "Ebola virus disease in Guinea (Situation as of 25 March 2014)". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ "Previous Updates: 2014 West Africa Outbreak". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 17 July 2019.

- ^ "Ebola update: Guinea president declares virus outbreak as national health emergency". Tech Times. 14 August 2014.

- ^ Andrew Soergel. "Ebola Resurgence in Guinea, Liberia Highlights West Africa's Containment Concerns – US News". U.S. News & World Report.

- ^ "Guinea Outbreak: Guinea Health Team Killed". BBC News. 19 September 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ a b Agencies. "Guinea residents 'refusing' Ebola treatment".

- ^ Stern, Jeffery E. (October 2014). "Hell in the Hot Zone". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ "Eight dead in attack on Ebola team in Guinea. 'Killed in cold blood.'". The Washington Post. 18 September 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Ebola outbreak: Guinea health team killed". BBC. 19 September 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Health workers killed in Guinea for distributing information about Ebola". The Advisory Board Company. 19 September 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Le gouverneur interdit tout les spectacles prévus pour la Tabaski, M. Thug réagit". ACTUU224.COM. 3 October 2014. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Fête de Tabaski: Toutes les manifestations culturelles interdites à Conakry..." Africaguinee.com. 3 October 2014. Archived from the original on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "WHO: Ebola Responses Roadmap Situation Report 8 October 2014". WHO. 8 October 2014. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ "Ebola: A new spike in cases in Guinea pushes Conakry treatment centre to the limit". MSF Canada. 9 October 2014. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ WHO (22 October 2014). "Ebola Response Roadmap Situation Report" (PDF). who.int. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ "BBC News – Ebola crisis: Guinea begins compensation payments". BBC News. 23 October 2014.

- ^ "Ebola response roadmap – Situation report". WHO. 12 November 2014. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ "Bandits in Guinea steal blood samples believed to be infected with Ebola". Yahoo News Canada. 21 November 2014. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "Ebola Response Roadmap Situation Report – 17 December 2014" (PDF). World Health organization. 17 December 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ "Ebola gone from Guinea". CBC News - Health. CBC/Radio Canada. 29 December 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ Reilly, Katie. "2 Test Positive for Ebola in Guinea". Time. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Fourth person dies of Ebola in Guinea". ABC News. 19 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Ebola clinic reopens in Guinea after virus resurfaces". news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Hundreds of contacts identified and monitored in new Ebola flare-up in Guinea". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Africa highlights: Tuesday 22 March 2016 as it happened - BBC News". BBC News. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Liberia Closes Border With Guinea After Ebola Flare-up". VOA. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Fifth person dies in Guinea Ebola flare-up". Reuters. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "WHO Director-General briefs media on outcome of Ebola Emergency Committee". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Ebola Situation Report - 30 March 2016 - Ebola". Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Hundreds in Guinea get Ebola vaccine in fight against flare-up". Fox News. 1 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Ebola claims another victim in Guinea as vaccinations ramped up". Yahoo News. 5 April 2016. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Ebola Vaccine Protects Against Deadly Virus". Bloomberg.com. 23 December 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ a b Burton, Thomas M.; Hackman, Michelle (24 April 2017). "Vaunted Ebola Vaccine Faces Questions". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ Maxmen, Amy (2017). "Ebola vaccine approved for use in ongoing outbreak". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22024.

- ^ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Democratic Republic of Congo approves experimental Ebola vaccine use | News | DW | 29 May 2017". DW.COM. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ "Russia to deliver Ebola vaccines to Guinea by end of June: Health Ministry - Xinhua | English.news.cn". news.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ "Beats, Rhymes and Ebola". Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ "Ebola virus causes outbreak of infectious dance tune". the Guardian. 27 May 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Ebola: Pop music a surprising weapon against the killer virus". 11 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ "Ebola in Perspective: The role of popular music in crisis situations in West Africa". Africa Is a Country. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ "African musicians band together to raise Ebola awareness". Health24.

- ^ "Sounds from the Sahel: Mali Song of the Week". Mali Interest Hub. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ "Tell Me the One About Ebola: How Jokes Spread Awareness". Bloomberg. 27 August 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- van Griensven, Johan; Edwards, Tansy; de Lamballerie, Xavier; Semple, Malcolm G.; Gallian, Pierre; Baize, Sylvain; Horby, Peter W.; Raoul, Hervé; Magassouba, N’Faly; Antierens, Annick; Lomas, Carolyn; Faye, Ousmane; Sall, Amadou A.; Fransen, Katrien; Buyze, Jozefien; Ravinetto, Raffaella; Tiberghien, Pierre; Claeys, Yves; De Crop, Maaike; Lynen, Lutgarde; Bah, Elhadj Ibrahima; Smith, Peter G.; Delamou, Alexandre; De Weggheleire, Anja; Haba, Nyankoye (7 January 2016). "Evaluation of Convalescent Plasma for Ebola Virus Disease in Guinea". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511812. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 5856332. PMID 26735992.

- Kerber, Romy; Krumkamp, Ralf; Diallo, Boubacar; Jaeger, Anna; Rudolf, Martin; Lanini, Simone; Bore, Joseph Akoi; Koundouno, Fara Raymond; Becker-Ziaja, Beate; Fleischmann, Erna; Stoecker, Kilian; Meschi, Silvia; Mély, Stéphane; Newman, Edmund N. C.; Carletti, Fabrizio; Portmann, Jasmine; Korva, Misa; Wolff, Svenja; Molkenthin, Peter; Kis, Zoltan; Kelterbaum, Anne; Bocquin, Anne; Strecker, Thomas; Fizet, Alexandra; Castilletti, Concetta; Schudt, Gordian; Ottowell, Lisa; Kurth, Andreas; Atkinson, Barry; Badusche, Marlis; Cannas, Angela; Pallasch, Elisa; Bosworth, Andrew; Yue, Constanze; Pályi, Bernadett; Ellerbrok, Heinz; Kohl, Claudia; Oestereich, Lisa; Logue, Christopher H.; Lüdtke, Anja; Richter, Martin; Ngabo, Didier; Borremans, Benny; Becker, Dirk; Gryseels, Sophie; Abdellati, Saïd; Vermoesen, Tine; Kuisma, Eeva; Kraus, Annette; Liedigk, Britta; Maes, Piet; Thom, Ruth; Duraffour, Sophie; Diederich, Sandra; Hinzmann, Julia; Afrough, Babak; Repits, Johanna; Mertens, Marc; Vitoriano, Inês; Bah, Amadou; Sachse, Andreas; Boettcher, Jan Peter; Wurr, Stephanie; Bockholt, Sabrina; Nitsche, Andreas; Županc, Tatjana Avšič; Strasser, Marc; Ippolito, Giuseppe; Becker, Stephan; Raoul, Herve; Carroll, Miles W.; Clerck, Hilde De; Herp, Michel Van; Sprecher, Armand; Koivogui, Lamine; Magassouba, N'Faly; Keïta, Sakoba; Drury, Patrick; Gurry, Cèline; Formenty, Pierre; May, Jürgen; Gabriel, Martin; Wölfel, Roman; Günther, Stephan; Caro, Antonino Di (16 September 2016). "Analysis of Diagnostic Findings From the European Mobile Laboratory in Guéckédou, Guinea, March 2014 Through March 2015". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 214 (Suppl 3): S250–S257. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw269. ISSN 0022-1899. PMC 5050480. PMID 27638946.

- Savini, Hélène; Janvier, Frédéric; Karkowski, Ludovic; Billhot, Magali; Aletti, Marc; Bordes, Julien; Koulibaly, Fassou; Cordier, Pierre-Yves; Cournac, Jean-Marie; Maugey, Nancy; Gagnon, Nicolas; Cotte, Jean; Cambon, Audrey; Nab, Christine Mac; Moroge, Sophie; Rousseau, Claire; Foissaud, Vincent; Greslan, Thierry De; Granier, Hervé; Cellarier, Gilles; Valade, Eric; Kraemer, Philippe; Alla, Philippe; Mérens, Audrey; Sagui, Emmanuel; Carmoi, Thierry; Rapp, Christophe (2017). "Occupational Exposures to Ebola Virus in Ebola Treatment Center, Conakry, Guinea". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 23 (8): 1380–1383. doi:10.3201/eid2308.161804. PMC 5547773. PMID 28726614.

- Gsell, Pierre-Stéphane; Camacho, Anton; Kucharski, Adam J.; Watson, Conall H.; Bagayoko, Aminata; Danmadji, Severine; Dean, Natalie E.; Diallo, Abdourahamane; Diallo, Abdourahmane (9 October 2017). "Ring vaccination with rVSV-ZEBOV under expanded access in response to an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Guinea, 2016: an operational and vaccine safety report". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 17 (12): 1276–1284. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30541-8. ISSN 1473-3099. PMC 5700805. PMID 29033032.

External links

[edit]- CDC Ebola in Guinea

- CDC Ebola outbreak map

- "Ebola outbreak: timeline". Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders.

KSF

KSF