Eclogue 5

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

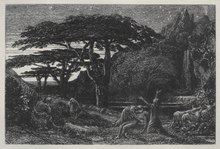

Eclogue 5 (Ecloga V; Bucolica V) is a pastoral poem by the Latin poet Virgil, one of his book of ten poems known as the Eclogues. In form, this is an expansion of the first Idyll of Theocritus, which contains a song about the death of the semi-divine herdsman Daphnis.[1] In the first half of Virgil's poem, the goatherd Mopsus sings a song lamenting the death of Daphnis; in the second half, his friend Menalcas sings a song of equal length telling of Daphnis' welcome among the gods, and the rites paid to him as a divinity.[1]

The poem has sometimes been held (though perhaps on slight grounds) to be allegorical, celebrating the apotheosis of Julius Caesar, which was confirmed by a solemn act passed in BC 42.[1] Another suggestion is that the "god" in this poem, which recalls Eclogue 1 in its language, represents not Julius Caesar but his adopted son Octavian.[2] Scholars have also noted in Virgil's deification of Daphnis echoes of the poet Lucretius's deification of the philosopher Epicurus.[3] According to another interpretation, Daphnis, in this and other eclogues, allegorically represents Lucretius himself.[4]

Summary

[edit]

Two herdsmen, Mopsus and Menalcas, meet and engage in a friendly contest, one singing about the death and the other about the deification of Daphnis.[5] The poem is amoebaean, and the 25 lines (20–44) which compose the song of Mopsus are replied to in 25 lines (56–80) by Menalcas.[5] The parallelism of the two songs is very marked: lines 20–23 are parallel to 56–59, 24–28 to 60–64, 29–35 to 65–71, 36–39 to 72–75, and 40–44 to 76–80.[5]

Introduction

[edit]- 1 - On meeting the skilled musician Mopsus, Menalcas suggests they should sing together. Perhaps they should sit under the elm trees. Mopsus admits he's junior to Menalcas, but all the same he suggests they should go to a certain cave.

- 8 - Menalcas suggests that only Amyntas is good enough to compete with Mopsus. Mopsus replies scornfully that Amyntas might as well try to compete with Apollo himself (implying that he is not as good as he thinks he is).[6]

- 10 - Menalcas suggests some themes Mopsus may like to sing about, while Tityrus minds the goats. Mopsus replies that he would like to sing a song he has recently composed; then let Amyntas try to beat him. Menalcas assures the touchy Mopsus that he is a much better singer than Amyntas. Meanwhile since they have reached the cave he asks Mopsus to begin.

Mopsus' song

[edit]- 20 - Mopsus sings how when Daphnis died, the nymphs wept at his funeral; Daphnis's mother lamented over his corpse, and called the gods cruel.

- 24 - No one took the cattle to drink or took sheep to the stream. The mountains and woods say that lions also mourned him.

- 29 - Daphnis had yoked tigers to a chariot and led Bacchic processions. Daphnis was the glory of all his people. After he died the goddess Pales and the god Apollo left the fields.

- 36 - Since he died weeds have been growing among the crops, and flowers have given way to thorns.

- 40 - Mopsus ends by calling on the herdsmen to strew the ground with leaves, make a tomb for Daphnis, and add an epitaph to the tomb.

Transition

[edit]- 45 - Menalcas praises the song and says that Mopsus is now the equal of his master both in music and song. He says that he himself is now going to sing a song raising Daphnis to the stars, since Daphnis loved him too. Mopsus encourages him, saying that he has heard that song praised by Stimichon and would love to hear it himself.

Menalcas' song

[edit]- 56 - Menalcas sings how Daphnis arrived at Olympus and saw the stars and clouds beneath his feet. The woods and countryside became cheerful and Pan, the herdsmen, and the Dryads were filled with joy.

- 60 - Sheep no longer feared the wolf, or deer the nets. The forested mountains joyfully raised their voices to the stars and the trees cried "He is a god, Menalcas!"

- 65 - Menalcas has made two altars for Daphnis and two for Phoebus, and will hold annual sacrifices with milk, olive oil, and wine.

- 72 - He says that Damoetas and Aegon will make music and Alphesiboeus will dance. They will do this for Daphnis whenever they pray to the nymphs and bless the fields.

- 76 - Daphnis's honour and name will remain forever, and the farmers will worship him annually just as they do Bacchus and Ceres.

Exchange of gifts

[edit]- 80 - Mopsus praises the song and wonders what gift he may give Menalcas. Menalcas presents Mopsus with a hemlock pipe,[7] on which he says he had composed Eclogues 2 and 3 (quoting their first lines). Mopsus in turn presents Menalcas with a beautiful shepherd's crook, which he says he did not give even to the handsome Antigenes,[8] though he begged for it often.

Analysis

[edit]Daphnis

[edit]

Daphnis is the ideal cowherd of pastoral poetry, which he was said to have invented, and his death is sung by Thyrsis in the first Idyll of Theocritus.[5] In Theocritus's poem, the herdsman Thyrsis describes the moments before Daphnis died: the gods Hermes, Priapus, and Cypris (Aphrodite) try to console him and persuade him not to die, but in vain. In Mopsus's song, Daphnis has now died and is being mourned by the nymphs. Menalcas's song describes Daphnis's ascent to Olympus and the rejoicing that follows.

The deification of Daphnis by Virgil has generally been supposed to describe the deification of Julius Caesar, and to have been written shortly after the order made by the triumvirs in 42 BC for the celebration of his birthday in the month Quinctilis, which was thenceforward called after him Julius.[9] However, many modern critics have pointed out that several elements in the description do not fit well with the life and character of Caesar. For example, Caesar was 56 when he died, whereas Daphnis is said to have been a boy (line 54); the great general could not in any way be described as a lover of peace, yet Daphnis "loves peace" (line 61).[10]

An alternative interpretation, proposed by Pulbrook (1978), is that the "god" mentioned in this poem (line 64) and the "god" described in very similar terms in Eclogue 1 (lines 6–7) were one and the same person, namely Julius Caesar's adopted son Octavian. During the three weeks of the battle of Philippi in 42 BC, according to the historian Dio, rumours reached Rome that Octavian had died. The language in both poems is very similar. In Eclogue 1, Tityrus praises a young man (iuvenis), who has created peace (otia fecit); he calls him a "god" and declares that he will make offerings to him every year. In Eclogue 5, Menalcas praises Daphnis, who is referred to as a boy (puer), who loves peace (amat otia); he calls him a "god" and declares that he will make offerings to him every year. In 42 BC Octavian was 21 years old, and could well be described as both "boy" and "young man".[11]

A third interpretation is that the god of Eclogue 5 represents the philosopher Epicurus. The eclogue contains at least six echoes of Lucretius's poem De Rerum Natura about the doctrines of Epicurus, of which the most notable is line 64: deus, deus ille Menalca 'he is a god, a god, Menalcas!', which recalls Lucretius 5.8: deus ille fuit, deus, inclute Memmi 'he was a god, a god, noble Memmius!', in which Lucretius praises Epicurus as a benefactor of mankind. It is therefore argued that it is possible that Daphnis represents Epicurus, whose philosophy Virgil followed.[12] A keyword is otia 'peace, leisure', which occurs in line 61 (amat bonus otia Daphnis 'good Daphnis loves leisure'), Eclogue 1.6 (deus nobis haec otia fecit 'a god has made this leisure for us') and Lucretius 5.1387, representing the Epicurean ideal of ἀταραξία 'freedom from disturbance'.[13]

Yet another possibility, suggested by Leah Kronenberg (2016), is that Daphnis represents the poet Lucretius, whose poetry combined intellectual brilliance with divine inspiration.[14] In lines 45–48 Menalcas praises Mopsus as a "divine poet" who has inherited the mantle of his "master" (the master being, in Kronenberg's view, Daphnis i.e. Lucretius); his song is like sleep for tired people in a pleasant grassy place, which could represent the Epicurean ideal of freedom from disturbance (otia, ἀταραξία). Mopsus, on the other hand, praises Menalcas's song as being like the roar of the south wind, the crashing of waves against the shore, or a torrent rushing down a rocky river bed; these are descriptions typical of the effect of sublimity in poetry, according to the author of the work On the Sublime. Thus one song represents the Apollonian aspect of Lucretius's poetry, and the other the Dionysian.

Kronenberg also sees an evocation of Lucretius in other eclogues, such as Eclogue 7, where Daphnis is portrayed as the master poet, Eclogue 8, where Daphnis is a figure apparently immune to the chains of love, and Eclogue 9, in which Daphnis is portrayed as gazing at the stars (an important part of Lucretius's book 5).[15] In Eclogue 3, Daphnis is said to have made Menalcas jealous by passing on his bow and "reeds" (arrows/panpipes) to a boy; Kronenberg suggests that the boy is Mopsus, and the gift is a symbol of Mopsus's inheriting the mantle of Lucretius.[16]

Menalcas

[edit]Menalcas in this poem is thought to represent Virgil, in view of the fact that at the end of the poem he claims to be the author of Eclogues 2 and 3, quoting them by their first lines. The name is found in Eclogue 3 as the singer who competes with Damoetas in a contest; in Eclogue 9 as a singer who made various poems including one begging Alfenus Varus to spare Virgil's home town of Mantua; and in Eclogue 10 as a cowherd who comes to console the love-sick Cornelius Gallus. Here compared with the young Mopsus he appears more mature, confident enough to boast in line 2 that he is good at making verses.[17] Despite at first annoying Mopsus by comparing him to Menalcas's beloved Amyntas, he quickly smoothes things over by reassuring him that Mopsus is the superior poet.

Mopsus

[edit]The name Mopsus recurs in Eclogue 8 as the rival lover who stole Nysa from the singer Damon. Otherwise it does not occur in bucolic poetry. In mythology, Mopsus was the name of a famous seer, who, being the son of the prophetess Manto, was the half-brother of Ocnus, the founder of Virgil's home town of Mantua. He appears in this eclogue to be a great rival in song of Amyntas, another youthful singer, who appeared in Eclogue 3 as a favourite of Menalcas, and in Eclogue 2 as having learned his skill in music from Corydon. After hearing his song, Menalcas praises him as now being the equal of his "master" (line 48). Many commentators, including Kronenberg, take this master to be Daphnis himself, but Lee suggests that the master is Stimichon, who is mentioned in line 55 as having recommended Menalcas's song to Mopsus.[18]

Alcon and Codrus

[edit]In lines 10–11 Menalcas suggests three subjects Mopsus might like to sing about: a love song about Phyllis, some praises of Alcon, or some criticisms of Codrus. In mythology, Codrus was the last king of Athens and Alcon was the son of a king of Athens; another Alcon is mentioned by Ovid (Metamorphoses 13.683) as a craftsman who made a wonderful mixing bowl given to Aeneas by Anius king of Delos. It has been proposed that "Codrus" (who appears again in Eclogue 7, where he is praised by Corydon and criticised by Thyrsis) is a pseudonym for a poet contemporary with Virgil,[19] but nothing is known of Alcon. Neither name is found in Theocritus.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Greenough, ed. 1883, p. 13.

- ^ Pulbrook (1978).

- ^ Mizera (1982).

- ^ Kronenberg (2016).

- ^ a b c d Page, ed. 1898, p. 131.

- ^ Lee (1977), p. 63.

- ^ The poisonous hemlock (cicuta) is a surprising material for a pipe. It is also mentioned in Eclogue 2.36 as the material of Corydon's pipe, as well as in Lucretius 5.1383 of a rustic pipe. It is thought that Virgil intends here to recall the Lucretius passage. See Mizera (1982), p. 371.

- ^ The name comes from Theocritus, Id. 7: Cucchiarelli (2012), Le Bucholiche, p. 317.

- ^ Page, ed. 1898, pp. 131–2.

- ^ Pulbrook (1978), p. 34.

- ^ Pulbrook (1978), p. 38.

- ^ Mizera (1982); Kronenberg (2016).

- ^ Mizera (1982), p. 24.

- ^ Kronenberg (2016), pp. 38–40.

- ^ Kronenberg (2016), pp. 42–50.

- ^ Kronenberg (2016), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Lee (1977).

- ^ Lee (1977), pp. 62–63.

- ^ Nisbet, R. G. (1995). "Review of WV Clausen, A Commentary on Virgil, Eclogues". The Journal of Roman Studies, 85, 320–321.

Sources

[edit]- Greenough, J. B., ed. (1883). Publi Vergili Maronis: Bucolica. Aeneis. Georgica. The Greater Poems of Virgil. Vol. 1. Boston, MA: Ginn, Heath, & Co. pp. 13–15. (public domain)

- Lee, Guy (1977). "A Reading of Virgil's Fifth Eclogue". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society. 23 (203): 62–70. doi:10.1017/S0068673500003928. JSTOR 44696640.

- Kronenberg, L. (2016). "Epicurean Pastoral: Daphnis as an Allegory for Lucretius in Vergil’s Eclogues". Vergilius (1959-), 62, 25–56.

- Mizera, S. M. (1982). "Lucretian Elements in Menalcas' Song, 'Eclogue' 5". Hermes, 110. Bd., H. 3 (1982), pp. 367–371.

- Page, T. E., ed. (1898). P. Vergili Maronis: Bucolica et Georgica. Classical Series. London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd. pp. 131–9. (public domain)

- Pulbrook, Martin (1978). "Octavian and Virgil's Fifth 'Eclogue'". The Maynooth Review / Revieú Mhá Nuad. 4 (2): 31–40. JSTOR 20556919.

KSF

KSF