Economic history of Spain

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 35 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 35 min

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2025) |

| History of Spain |

|---|

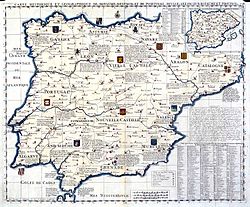

18th century map of Iberia |

| Timeline |

This article covers the development of Spain's economy over the course of its history.

Ancient era

[edit]Iberians, roughly located in the South and East, and Celts in the North and West of the Iberian Peninsula were the major earliest groups in what is now Spain (a third, so-called Celtiberian culture seems to have developed in the inner part of the Peninsula, where both groups were in contact).

Carthaginians and Greeks also traded with Spain and established their own colonies on the coast. Spain's mineral wealth and access to metals made it an important source of raw material during the early metal ages. Carthage conquered parts of Iberia after the First Punic War. After defeating Carthage in the Second Punic War, the Romans governed all of the Iberian Peninsula for centuries, expanding and diversifying the economy and extending Hispanic trade with the greater Republic and Empire.

Middle Ages

[edit]While most of western Europe fell into a Dark Age after the decline of the Roman Empire, those kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula that today are known as Spain maintained their economy.[citation needed] First, the Visigoths replaced the Roman imperial administrators (an international class at the top echelons). They established themselves as nobility. The kingdom had some degree of centralized power at their capital, which was eventually moved to Toledo from Toulouse. The Roman municipal and provincial governorships continued but the imperial superstructure of diocese and prefecture was of course completely gone as there was no need for it: these had existed to coordinate imperial defense and provide uniform administrative oversight, and symbolized as nothing else, except the professional army, the presence of the Roman. Though it suffered some decline, most Roman law and many physical infrastructures such as roads, bridges, aqueducts, and irrigation systems, were maintained to varying degrees, unlike the complete disintegration that occurred in most other former parts of the western empire with the exception of parts of Italy. Later, when the Moors occupied large parts of the Iberian Peninsula alongside the Catholic kingdoms, they also maintained much of this Roman legacy; in fact, as time went on they had Roman infrastructure repaired and extended. Meanwhile, in the countryside, where most people had always lived, life went on much as it had in Roman times, but with improvements due to the repair and extension of irrigation systems, and the introduction of novel crops and agricultural practices from the Islamic world. While trade dwindled in most of the former Roman lands in Europe, trade survived to some degree in Visigothic Spain and flourished under the Moors through the integration of Al-Andalus (Moorish Spain) with the Mediterranean trade of the Islamic world. After 800 years of intermittent warring, the Catholic kingdoms had gradually become more powerful and sophisticated and eventually expelled all the Moors from the Peninsula.

The Crown of Castile, united with the Crown of Aragon, had merchant navies that rivaled that of the Hanseatic League and Venice. Like the rest of late medieval Europe, restrictive guilds closely regulated all aspects of the economy-production, trade, and even transport. The most powerful of these corporations, the mesta, controlled the production of wool, Castile's chief export.

Dynastic union and exploration

[edit]The Reconquista allowed the Catholic Monarchs to divert their attention to exploration. In 1492, Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borja, a Valencian) formally approved the division of the unexplored world between kingdoms of what is today Spain and Portugal. New discoveries and conquests came in quick succession.

In 1493, when Christopher Columbus brought 1,500 colonists with him on his second voyage, a royal administrator had already been appointed for what the Catholic kingdoms referred to as the Indies. The Council of the Indies (Consejo de Indias), established in 1524 acted as an advisory board on colonial affairs, and the House of Trade (Casa de Contratación) regulated trade with the colonies.

Gold and silver from the New World

[edit]

Following the discovery of America and the colonial expansion in the Caribbean and Continental America, valuable agricultural products and mineral resources were introduced into Spain through regular trade routes. New products such as potatoes, tomatoes and corn had a long-lasting impact on the Spanish economy, but more importantly on European demographics. Gold and silver bullion from American mines were used by the Spanish Crown to pay for troops in the Netherlands and Italy, to maintain the emperor's forces in Germany and ships at sea, and to satisfy increasing consumer demand at home. However, the large volumes of precious metals from America led to inflation, which had a negative effect on the poorer part of the population, as goods became overpriced. This also hampered exports, as expensive goods could not compete in international markets. Moreover, the large cash inflows from silver hindered the industrial development in Spain as entrepreneurship seems to be indispensable.[1]

Domestic production was heavily taxed, driving up prices for Aragon and Castile-made goods, but especially in Castile where the tax burden was greater. The sale of titles to entrepreneurs who bought their way up the social ladder (a practice commonly found all over Europe), removing themselves from the productive sector of the economy, provided additional funds.

The overall effect of mass deportation, plague and emigration reduced peninsular Spain's population from over 8 million in the last years of the 16th century to under 7 million by the mid-17th century, with Castile the most severely affected region (85% of the Kingdom's population were in Castile), as an example, in 1500, the population of Castile was 6 million, while 1.25 million lived in the Crown of Aragon which included Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearic Islands.

The Spanish economy began to fall behind the British economy in terms of GDP per capita during the middle of the seventeenth century. The explanations for this divergence are unclear, but "the divergence comes too late to have any medieval origins, whether cultural or institutional" and "it comes too early... in order for the Napoleonic Invasions to be blamed."[2]

Colonization and development of institutions

[edit]Despite the fact that the Spanish economy in this period had obtained cheap inputs from the colonization process which provided different advantages, it had not led to sustainable economic growth. At the first steps flows of capital and investment unions between nobles and successful merchants provide a development of Spanish cities. However due to current laws of the 16th century the Crown had a right for 20% of capital earned from the colonization process.[3] Besides the tax burden we also have to highlight that colonial trade itself was mostly indirectly monopolized by the crown in Spain. In some sense this prevented the effective investment process, especially because overtime state participation had started to increase in order to meet rising expansion costs. Moreover because of such allocation of the resources the process of the development of institutions and utilizing of colonization resources was blocked mostly by the crown. Country was moving along the path of absolutism and the crown had continued to utilize its power and increase taxes for global expansion, including unsuccessful wars.[4][5]

In order to illustrate ineffective allocation of the resources which had led to institutional issues one can utilize two examples. Real wages of craftsmen and builders in Madrid during this period can illustrate the taxation burden. Substantial increase in the 16th century was based on the cheap inputs due to the colonization process and arrival of the Court in 1561. However ineffective fiscal and monetary policy as well as centralization of the governance had led to the decrease which took place from 1621 to 1680 and then until 1700 wages were at stable low level.[6] The other example of such a proxy of economic prosperity are demographic indices. Tax burden had led to the decrease of living standards in this period and drop of marriage rates. Where in England cheap inputs had been utilized in order to develop new market institutions in Spain ineffective governance didn't let it happen.[7]

Bourbon reforms

[edit]A slow economic recovery began in the last decades of the 17th century under the Habsburgs. Under the Bourbons, government efficiency was improved, especially under Charles III's reign. The Bourbon reforms, however, resulted in no basic changes in the pattern of property holding. The nature of bourgeois class consciousness in Aragon and Castile hindered the creation of a middle-class movement. At the instance of liberal thinkers including Campomanes, various groups known as "Economic Societies of friends of the Country" were formed to promote economic development, new advances in the sciences, and Enlightenment philosophy (see Sociedad Económica de los Amigos del País). However, despite the development of a national bureaucracy in Madrid, the reform movement could not be sustained without the patronage of Charles III, and it did not survive him.

Jan Bergeyck (advisor to Philip V) "Disorder I have found here is beyond all imagination". Castile's exchequer still used Roman numerals and there was no proper accounting.[8]

Napoleon and the War of Independence

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2025) |

Spain's American colonies took advantage of the postwar chaos to proclaim their independence. By 1825 only Cuba and Puerto Rico remained under the Spanish flag in the New World. When Ferdinand VII was restored to the throne in 1813 and expended wealth and manpower in a vain effort to reassert control over the colonies. The move was unpopular among liberal officers assigned to the American wars.

1822 to 1898

[edit]During the 19th century, Spain fell behind other European economies.[9]

The economy was heavily focused around agricultural goods. The period saw regional industrialization in Catalonia and the Basque Country and the construction of railways in the second half of the nineteenth century helped alleviate some of the isolation of the interior but generally little changed for much of the country as political instability, uprisings and unstable governments slowed or undermined economic progress.

1898 to 1920

[edit]At the beginning of the 20th century, Spain was still mostly rural; most of the large-scale, modern industry existed as textile mills around Barcelona in Catalonia and in the metallurgical plants of the Basque provinces and some shipyards around the country.{ The loss of Cuba and the Philippines benefited Spain by causing capital to return and to be invested in updated domestic industries.[citation needed] But even with the stimulus of World War I, only in Catalonia and in two Basque provinces (Biscay and Gipuzkoa) did the value of manufacturing output in 1920 exceed that of agricultural production. Agricultural productivity was generally low compared with that of other West European countries because of a number of deficiencies: backward technology, lack of large irrigation projects, inadequate rural credit facilities, outmoded landtenure practices, as well as the age-old problems of difficult terrain, unreliable climate, isolation and difficult transportation in the rugged interior. Financial institutions were relatively undeveloped. The Bank of Spain (Banco de España) was still privately owned, and its public functions were restricted to currency issuance and the provision of funds for state activities. The state largely limited itself to such traditional activities as defense and the maintenance of order and justice. Road building, education, and a few welfare activities were the only public services that had any appreciable impact on the economy.

Primo de Rivera

[edit]A General, Miguel Primo de Rivera, was appointed prime minister by the king after a successful coup d'état and for seven years dissolved parliament and ruled through directorates and the aid of the military until 1930.

Spanish neutrality during World War I (which allowed the country to trade with all belligerents) led to a temporary economic recovery. The precipitous economic decline in 1930 undercut support for the government from special-interest groups. Criticism from academics mounted. Bankers expressed disappointment at the state loans that his government had tried to float. An attempt to reform the promotion system cost him the support of the army and, in turn, the support of the king. Primo de Rivera resigned and died shortly afterward in exile.[citation needed]

Second Republic (1931–36)

[edit]The republican government substituted the monarchy and inherited the international economic crisis as well. Three different governments ruled during the Second Spanish Republic, failing to execute numerous reforms, including land reform. General strikes were common and the economy stagnated.

During the Spanish Civil War, the country split into two different centralized economies, and the whole economic effort was redirected to the war industry. According to recent research,[10] growth is harmed during civil wars due to the huge contraction on private investment, and such was the case with the Spanish divided economy.

Franco era (1939–75)

[edit]Recovery (1939-1958)

[edit]

Spain emerged from the civil war with formidable economic problems. Gold and foreign exchange reserves had been virtually wiped out, the massive devastation of war had reduced the productive capacity of both industry and agriculture. To compound the difficulties, even if the wherewithal had existed to purchase imports, the outbreak of World War II rendered many needed supplies unavailable. The end of the war did not improve Spain's plight because of subsequent global shortages of raw materials, and peacetime industrial products. Spain's European neighbours faced formidable post-war reconstruction problems of their own, and, because of their awareness that the Nationalist victory in the Spanish Civil War had been achieved with the help of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, they had no inclination to include Spain in any multilateral recovery programs or trade. For a decade following the Civil War's end in 1939, the wrecked and isolated economy remained in a state of severe depression.[11]

Branded an international outcast for its pro-Axis bias during World War II, Spain was not invited to join the Marshall Plan. Francisco Franco's regime sought to provide for Spain's well-being by adopting a policy of economic self-sufficiency. Autarky was not merely a reaction to international isolation; it was also rooted in more than half a century of advocacy from domestic economic pressure groups. Furthermore, from 1939 to 1945, Spain's military chiefs genuinely feared an Allied invasion of the Peninsula and, therefore, sought to avert excessive reliance on foreign armaments.[11]

With the war devastation and trade isolation, Spain was much more economically backward in the 1940s than it had been a decade earlier. Inflation soared, economic reconstruction faltered, food was scarce, and, in some years, Spain registered negative growth rates. By the early 1950s, per capita gross domestic product (GDP) was barely 40% of the average for West European countries. Then, after a decade of economic stagnation, a tripling of prices, the growth of a black market, and widespread deprivation, gradual improvement began to take place. The regime took its first faltering steps toward abandoning its pretensions of self-sufficiency and towards a transformation of Spain's economic system. Pre-Civil War industrial production levels were regained in the early 1950s, though agricultural output remained below prewar levels until 1958.[11]

A further impetus to economic liberalization came from the September 1953 signing of a mutual defense agreement, the Pact of Madrid, between the United States and Spain. In return for permitting the establishment of United States military bases on Spanish soil, the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower provided substantial economic aid to the Franco regime. More than US$1 billion in economic assistance flowed into Spain during the remainder of the decade as a result of the agreement. Between 1953 and 1958, Spain's gross national product (GNP) rose by about 5% per annum.[11]

The years from 1951 to 1956 were marked by much economic progress, but the reforms of the period were implemented irregularly, and were poorly coordinated. One large obstacle to the reform process was the corrupt, inefficient, and bloated bureaucracy. By the mid-1950s, the inflationary spiral had resumed its upward climb, and foreign currency reserves that had stood at US$58 million in 1958 plummeted to US$6 million by mid-1959. The growing demands of the emerging middle class—and of the ever-greater number of tourists—for the amenities of life, particularly for higher nutritional standards, placed heavy demands on imported food and luxury items. At the same time, exports lagged, largely because of high domestic demand and institutional restraints on foreign trade. The peseta fell to an all-time low on the black market, and Spain's foreign currency obligations grew to almost US$60 million.[11]

A debate took place within the regime over strategies for extricating the country from its economic impasse, and Franco finally opted in favor of a group of technocrats. The group included bankers, industrial executives, some academic economists, and members of the Roman Catholic lay organization, Opus Dei.[11]

During the 1957-59 period, known as the pre-stabilization years, economic planners contented themselves with piecemeal measures such as moderate anti-inflationary stopgaps and increases in Spain's links with the world economy. A combination of external developments and an increasingly aggravated domestic economic crisis, however, forced them to engage in more far-reaching changes.[11]

As the need for a change in economic policy became manifest in the late 1950s, an overhaul of the Council of Ministers in February 1957 brought to the key ministries a group of younger men, most of whom possessed economics training and experience. This reorganization was quickly followed by the establishment of a committee on economic affairs and the Office of Economic Coordination and Planning under the prime minister.[11]

Such administrative changes were important steps in eliminating the chronic rivalries that existed among economic ministries. Other reforms followed, the principal one being the adoption of a corporate tax system that required the confederation of each industrial sector to allocate an appropriate share of the entire industry's tax assessment to each member firm. Chronic tax evasion was consequently made more difficult, and tax collection receipts rose sharply. Together with curbs on government spending, in 1958 this reform created the first government surplus in many years.[11]

More drastic remedies were required as Spain's isolation from the rest of Western Europe became exacerbated. Neighboring states were in the process of establishing the EC and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA—see Glossary). In the process of liberalizing trade among their members, these organizations found it difficult to establish economic relations with countries wedded to trade quotas and bilateral agreements, such as Spain.[11]

Spanish Miracle (1959-1974)

[edit]Spanish membership in these groups was not politically possible, but Spain was invited to join a number of other international institutions. In January 1958, Spain became an associate member of the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC), which became the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in September 1961. In 1959 Spain joined the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. These bodies immediately became involved in helping Spain to abandon the autarkical trade practices that had brought its reserves to such low levels and that were isolating its economy from the rest of Europe.[11]

In December 1958, after seven months of preparation and drafting, aided by IMF, Spain unveiled its Stabilization Plan on June 30, 1959. The plan's objectives were twofold: to take the necessary fiscal and monetary measures required to restrict demand and to contain inflation, while, at the same time, liberalizing foreign trade and encouraging foreign investment. The plan's initial effect was deflationary and recessionary, leading to a drop in real income and to a rise in unemployment during its first year. The resultant economic slump and reduced wages led approximately 500,000 Spanish workers to emigrate in search of better job opportunities in other West European countries. Nonetheless, its main goals were achieved. The plan enabled Spain to avert a possible suspension of payments abroad to foreign banks holding Spanish currency, and by the close of 1959, Spain's foreign exchange account showed a US$100-million surplus. Foreign capital investment grew sevenfold between 1958 and 1960, and the annual influx of tourists began to rise rapidly, bringing in very much needed foreign exchange along remittances from Spanish workers abroad.[11]

In 1959, Spain entered the greatest cycle of industrialization and prosperity it had ever known. Foreign aid took the form of US$75 million in drawing rights from the IMF, US$100 million in OEEC credits, US$70 million in commercial credits from the Chase Manhattan Bank and the First National City Bank, US$30 million from the Export-Import Bank of the United States, and funds from United States aid programs. Total foreign backing amounted to US$420 million. The principal lubricants of the economic expansion, however, were the hard currency remittances of one million Spanish workers abroad, which are estimated to have offset 17.9% of the total trade deficit from 1962 to 1971; the gigantic increase in tourism that drew more than 20 million visitors per year by the end of the 1960s, accounting by then for 9% of GNP; a car industry that grew at a staggering compound rate of 21.7% per year from 1958 to 1972; and direct foreign investment, which between 1960 and 1974 amounted to an impressive US$7.6 billion. More than 40% of this investment came from the United States, almost 17% came from Switzerland, and the Federal Republic of Germany and France each accounted for slightly more than 10%. By 1975 foreign capital represented 12.4% of the total invested in Spain's 500 largest industrial firms. More important than the actual size of the foreign investment was the access it gave Spanish companies to up to date technology. An additional billion dollars came from foreign sources through a variety of loans and credit devices.[11]

To help achieve rapid development, there was massive government investment through key state-owned companies like the national industrial conglomerate Instituto Nacional de Industria, the mass-market car company SEAT in Barcelona, the shipbuilder Empresa Nacional Bazán. With foreign access to the Spanish domestic market restricted by heavy tariffs and quotas, these national companies led the industrialisation of the country, restoring the prosperity of old industrial areas like Barcelona and Bilbao and creating new industrial areas, most notably around Madrid. Although there was considerable economic liberalisation in the period these enterprises remained under state control.[11] As these developments steadily converted Spain's economic structure into one more closely resembling a free-market economy.

The success of the stabilization program was attributable to a combination of good luck and good management and the impressive development during this period was referred to as the "Spanish miracle".[13] From 1959 to 1974, Spain had the next fastest economic growth rate after Japan. The boom came to an end with the oil shocks of the 1970s and government instability during the transition back to democracy after Franco's death in 1975.[11]

Labor unions

[edit]During the Civil War anarchists, and syndicalists took control over much of Spain. Implementing worker control through a system of libertarian socialism with organizations like the anarcho-syndicalist CNT organizing throughout Spain. Unions were particularly present in Revolutionary Catalonia, in which anarchists were already the basis for most of society with over 90% of industries being organized through work cooperatives.[14] The republicans, anarchists and leftists were expelled when Franco took over in 1939.

The Francoist regime saw the worker movement and union movement as a threat, Franco banned all existing trade unions and set up the government controlled Spanish Syndical Organization as the only legal Spanish trade union, with the organization existing to maintain Franco's power.[15]

Many anarchists, communists and leftists turned towards insurgent tactics as Franco implemented wide reaching authoritarian policies, with the CNT and other unions being forced underground. Anarchists would operate covertly setting up local organizations and underground movements to challenge Franco.[16] On the 20 of December the ETA assassinated Luis Carrero. The death of Carrero Blanco had numerous political implications. By the end of 1973, the physical health of Francisco Franco had declined significantly, and it epitomized the final crisis of the Francoist regime. After his death, the most conservative sector of the Francoist State, known as the búnker, wanted to influence Franco so that he would choose an ultraconservative as Prime Minister. Finally, he chose Carlos Arias Navarro, who originally announced a partial relaxation of the most rigid aspects of the Francoist State, but quickly retreated under pressure from the búnker. After Franco's death Arias Navarro began relaxing Spanish authoritarianism.

During the Spanish transition to democracy, leftist organizations became legal once again. In modern Spain trade unions now contribute massively towards Spanish society, being again the main catalyst for political change in Spain, with cooperatives employing large parts of the Spanish population such as the Mondragon Corporation. Trade unions today lead mass protests against the Spanish government, and are one of the main vectors of political change.[17]

Post-Franco period (1975–1980s)

[edit]Franco's death in 1975 and the ensuing transition to democratic rule diverted Spaniards' attention from their economy.[18]

The return to democracy coincided with an explosive quadrupling of oil prices, which had an extremely serious effect on the economy because Spain imported 70% of its energy, mostly in the form of Middle Eastern oil. Nonetheless, the interim centrist government of Adolfo Suarez Gonzalez, which had been named to succeed the Franco regime by King Juan Carlos, did little to shore up the economy or even to reduce Spain's dependence on imported oil, although there was little that could be done as the country had little in the way of hydrocarbon deposits. A virtually exclusive preoccupation with the politics of democratization during the politically and socially unstable period when the new constitution was drafted and enacted, absorbed most of Spain's politics and administration at the expense of economic policy.[11]

Because of the failure to adjust to the changed economic environment brought on by the two oil price shocks of the 1970s, Spain quickly confronted plummeting productivity, an explosive increase in wages from 1974 to 1976, a reversal of migration trends as a result of the economic slump throughout Western Europe, and the steady outflow of labor from agricultural areas despite declining job prospects in the cities. All these factors contributed to a sharp rise in the unemployment rate. Government budgetary deficits swelled, as did large social security cost overruns and the huge operating losses incurred by a number of public-sector industries. Energy consumption, meanwhile, remained high.[11]

When the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party government headed by Felipe González took office in late 1982, inflation was running at an annual rate of 16%, the external current account was US$4 billion in arrears, public spending was large, and foreign exchange reserves had become dangerously depleted. In coping with the situation, however, the Gonzalez government had one asset that no previous post-Franco government had enjoyed, namely, a solid parliamentary majority in both houses of the Cortes (Spanish Parliament). With this majority, it was able to undertake unpopular austerity measures that earlier governments had not.[11]

The Socialist government opted for pragmatic, orthodox monetary and fiscal policies, together with a series of vigorous retrenchment measures. In 1983 it unveiled a program that provided a more coherent and long-term approach to the country's economic ills. Renovative structural policies—such as the closing of large, unprofitable state enterprises—helped to correct the relatively poor performance of the economy. The government launched an industrial reconversion program, brought the problem-ridden social security system into better balance, and introduced a more efficient energy-use policy. Labor market flexibility was improved, and private capital investment was encouraged with incentives.[11]

By 1985 the budgetary deficit was brought down to 5% of GNP, and it dropped to 4.5% in 1986. Real wage growth was contained, and it was generally kept below the rate of inflation. Inflation was reduced to 4.5% in 1987, and analysts believed it might decrease to the government's goal of 3% in 1988.[11]

Efforts to modernize and to expand the economy together with a number of factors fostered strong economic growth in the 1980s. Those factors were the continuing fall in oil prices, increased tourism, and a massive upsurge in the inflow of foreign investment. Thus, despite the fact that the economy was being exposed to foreign competition in accordance with EC requirements, the Spanish economy underwent rapid expansion without experiencing balance of payments' constraints.[11][19]

In the words of the OECD's 1987-88 survey of the Spanish economy, "following a protracted period of sluggish growth with slow progress in winding down inflation during the late 1970s and the first half of the 1980s, the Spanish economy has entered a phase of vigorous expansion of output and employment accompanied by a marked slowdown of inflation."[20] In 1981 Spain's GDP growth rate had reached a nadir by registering a rate of negative 0.2%; it then gradually resumed its slow upward ascent with increases of 1.2% in 1982, 1.8% in 1983, 1.9% in 1984, and 2.1% in 1985. The following year, however, Spain's real GDP began to grow strongly, registering a growth rate of 3.3% in 1986 and 5.5% in 1987. Although these growth rates were less than those of the economic miracle years, they were among the strongest of the OECD. Analysts projected a rise of 3.8% in 1988 and of 3.5% in 1989, a slight decline but still roughly double the EC average. They expected that declining interest rates and the government's stimulative budget would help sustain economic expansion. Industrial output, which rose by 3.1% in 1986 and by 5.2% in 1987, was also expected to maintain its expansive rate, growing by 3.8% in 1988 and by 3.7% in 1989.[11]

A prime force generating rapid economic growth was increased domestic demand, which grew by a steep 6% in 1986 and by 4.8% in 1987, in both years exceeding official projections. During 1988 and 1989, analysts expected demand to remain strong, though at slightly lower levels. Much of the large increase in demand was met in 1987 by an estimated 20% jump in real terms in imports of goods and services.[11]

In the mid-1980s, Spain achieved a strong level of economic performance while simultaneously lowering its rate of inflation to within two points of the EC average. However, its export performance, though increasing, raised concerns over the existing imbalance between import and export growth.[11]

European integration (1985–2000)

[edit]

After Franco's death in 1975, the country returned to democracy in the form of a constitutional monarchy in 1978, with elections being held in 1977 and with the constitution being ratified in 1978. The move to democracy saw Spain become more involved with the European integration.

Felipe Gonzalez became prime minister when his Socialist Party won the 1982 elections. He enacted a number of liberal reforms, increasing civil liberties and implementing universal free education for those 16 and younger. He also lobbied successfully for Spain to join the European Economic Community (EEC) and to remain part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

The European Union at the time Spain joined, in 1986, existed primarily as a trading union - the EEC, and better trade links were vital to the fragile Spanish economy. Unemployment was high, about 18 percent, and the Spanish GDP was 71 percent of the EU average. The single market and European funding offered a chance to bring the Spanish economy up to the standards of the rest of Western Europe, along with the support of Spain's wealthier neighbors. There was the promise of lucrative deals with influential countries such as Germany, France and the UK.

Although the Spanish Miracle years (1959–1974) witnessed unprecedented improvements in infrastructure and social services, Spain still lagged behind most of Western Europe. Education was limited, women were largely excluded from the workforce, health care was largely private and unevenly distributed and the country's infrastructure was relatively poor. In 1985, Spain had only 2,100 km (1,300 mi) of motorways. Since the end of the economic miracle in 1974, the country's economy had been stagnant. Joining the European Economic Community was perceived by most of the population as a way to restart the process of modernization and improvement of the population's average purchasing power.

Spain joined the European Economic Community, as the European Union was then known, in January 1986 at the same time as neighbor Portugal. Membership ushered the country into opening its economy, modernizing its industrial base and revising economic legislation to open its previously protected markets to foreign competition. With help of EU funds (Structural Funds and Cohesion Funds, European Regional Development Fund, etc.) Spain greatly improved infrastructures, increased GDP growth, reduced the public debt to GDP ratio. Spain has been a driving force in the European community ever since. The country was a leading proponent of the EU single currency, the euro, long before it had been put into circulation. Together with the other founding euro members, it adopted the new physical currency on January 1, 2002. On that date Spain terminated its historic peseta currency and replaced it with the euro, which has become its national currency shared the rest of the Eurozone. This culminated a fast process of economic modernization even though the strength of the euro since its adoption has raised concerns regarding the fact that Spanish exports outside the European Union are being priced out of the range of foreign buyers, with the country losing monetary sovereignty in favour of the European Central Bank, which must look after several different -often opposed- national interests.

In the early 1990s Spain, like most other countries, was hit by the early 1990s recession. which coincided with the end of the construction push put in place for the Barcelona Olympics.

Boom (1997–2007)

[edit]

The country was confronted with very high unemployment, entrenched by its then rigid labour market. However the economy began to recover during the first José María Aznar administration (1996-2000), driven by a return of consumer confidence, increased private consumption and liberalization and deregulation reforms aiming to reduce the state's role in the market place. Unemployment at 7.6% (October 2006) represented a significant improvement from the 1980s levels and a better rate than the one of Germany or France at the time. Devaluations of the peseta during the 1990s made Spanish exports more competitive. By the late 1990s economic growth was strong, employment grew strongly, although unemployment remained high, as people returned to the job market and confidence in the economy returned. The last years of the 1990s saw property values begin to increase.

The Spanish economy was being credited for having avoided the virtual zero growth rate of some of its largest partners in the EU (namely France, Germany and Italy) in the late 1990s and at the beginning of the 21st century. In 1995 Spain started an impressive economic cycle marked by an outstanding economic growth, with figures around 3%, often well over this rate.[21]

Growth in the decade prior to 2008 steadily closed the economic gap between Spain and its leading partners in the EU. For a moment, the Spanish economy was regarded as one of the most dynamic within the EU, even able to replace the leading role of much larger economies like the ones of France and Germany, thus subsequently attracting significant amounts of native and foreign investment.[22] Also, during the period spanning from the mid 1980s through the mid 2000s, Spain was second only to France in being the most successful OECD country in terms of reduced income inequality over this period.[23] Spain also made great strides in integrating women into the workforce. From a position where the role of Spanish women in the labour market in the early 1970s was similar to that prevailing in the major European countries in the 1930s, by the 1990s Spain had achieved a modern European profile in terms of economic participation by women.[24]

Spain joined the Eurozone in 1999. Interest rates dropped and the property boom accelerated. By 2006 property prices had doubled from a decade earlier. During this time construction of apartments and houses increased at a record rate and immigration into Spain increased into the hundreds of thousands a year as Spain created more new jobs than the rest of Eurozone combined.[citation needed] Along with the property boom, there was a rapid expansion of service industry jobs.

Convergence with the European Union

[edit]Due to its own economic development and the EU enlargements up to 27 members (2007), Spain as a whole exceeded (105%) the average of the EU GDP in 2006 placing it ahead of Italy (103% for 2006). As for the extremes within Spain, three regions in 2005 were included in the leading EU group exceeding 125% of the GDP average level (Madrid, Navarre and the Basque Autonomous Community) and one was at the 85% level (Extremadura).[25] These same regions were on the brink of full employment by then.

According to the growth rates post 2006, noticeable progress from these figures happened until early 2008, when the Spanish economy was heavily affected by the Great Recession.[26]

In this regard, according to Eurostat's estimates for 2007 GDP per capita for the EU-27. Spain happened to stay by that time at 107% of the level, well above Italy who was still above the average (101%), and catching up with countries like France (111%).[27]

Economic crisis (2008–2013)

[edit]

The 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession ended the Spanish property bubble, causing a property crash. Construction collapsed and unemployment began to rise rapidly. The property crash led to a collapse of credit as banks hit by bad debts cut back lending, causing a severe recession. As the economy shrank, government revenue collapsed and government debt began to climb rapidly. By 2010, the country faced severe financial problems and got caught up in the European sovereign debt crisis.

In 2012, unemployment rose to a record high of 25 percent.[29] On 25 May 2012, Bankia, at that time the fourth largest bank of Spain with 12 million customers, requested a bailout of €19 billion, the largest bank bailout in the nation's history.[30][31] The new management, led by José Ignacio Goirigolzarri reported losses before taxes of 4.3 billion euros (2.98 billion euros taking into account a fiscal credit) compared to a profit of 328 million euros reported when Rodrigo Rato was at the head of Bankia until May 9, 2012.[32] On June 9, 2012, Spain asked Eurozone governments for a bailout worth as much as 100 billion euros ($125 billion) to rescue its banking system as the country became the biggest euro economy until that date, after Ireland, Greece and Portugal, to seek international aid due to its weaknesses amid the European sovereign debt crisis.[33] A Eurozone official told Reuters in July 2012 that Spain conceded for the first time at a meeting between Spanish Economy Minister Luis de Guindos and his German counterpart Wolfgang Schaeuble, it might need a bailout worth 300 billion euros if its borrowing costs remained unsustainably high. On August 23, 2012, Reuters reported that Spain was negotiating with euro zone partners over conditions for aid to bring down its borrowing costs.[34]

Recovery (2014 to present)

[edit]After deep austerity measures and major reforms, Spain exited the deep and long recession in 2013 and its economy began growing once again but despite the expansion of the number of jobs, the unemployment rate still stood at the historically high level of 22.6% as late as April 2015.[35] In 2014, the Spanish economy grew 1,4%,[36] accelerating to 3.4% in 2015 and 3.3% in 2016[37][38] and by 3.1% in 2017.[39][40] Experts say that the economy will moderate in 2018 to between 2.5% and 3%. In addition to this, the unemployment rate has been reduced during the years of recovery, standing at 16.55% in 2017.[41]

Whilst the COVID-19 pandemic caused exports to fall dramatically, the 2023 year's export figure showed a 20.2% increase compared to figures in October 2019. In terms of imports, Spain noted a 27.1% increase compared to the level seen in October 2019. In 2023, Spain had an account surplus of 3% of GDP, the best figure recorded since 2018, demonstrating that Spain had more exports and incoming payments than imports and outgoing payments to other countries.[42]

See also

[edit]- Economy of Spain

- Science and technology in Spain

- Agriculture in Spain

- Economic history of Europe

- Economic history of Portugal

- Economic history of the world

- Plastimetal

- Contemporary history of Spain

References

[edit]- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 159. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ^ Palma, Nuno; Santiago-Caballero, Carlos (2024), Herranz-Loncán, Alfonso; Igual-Luis, David; Vilar, Hermínia Vasconcelos; Freire Costa, Leonor (eds.), "Patterns of Iberian Economic Growth in the Early Modern Period", An Economic History of the Iberian Peninsula, 700–2000, Cambridge University Press, pp. 251–277, doi:10.1017/9781108770217.012, hdl:10016/29185, ISBN 978-1-108-48832-7

- ^ Kamen, Henry (2004). Empire: how Spain became a world power, 1492-1763. New York: Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-093264-0.

- ^ Acemoglu, Daron; Johnson, Simon; Robinson, James A (2001-12-01). "The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation". American Economic Review. 91 (5): 1369–1401. doi:10.1257/aer.91.5.1369. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ^ Alvarez-Nogal, C.; De La Escosura, L. P. (2007-12-01). "The decline of Spain (1500-1850): conjectural estimates". European Review of Economic History. 11 (3): 319–366. doi:10.1017/S1361491607002043. hdl:10016/3932. ISSN 1361-4916.

- ^ Andrés Ucendo, José Ignacio; Lanza García, Ramón (2016), "FOS: Humanities", Prices and real wages in seventeenth-century Madrid, Dataverse Admin, e-cienciaDatos, doi:10.21950/5sciio, retrieved 2023-07-06

- ^ Moreno-Almárcegui, Antonio; Sánchez-Barricarte, Jesús J. (2016-04-14). "Demographic causes of urban decline in 17th century Spain". Annales de démographie historique. 130 (2): 133–159. doi:10.3917/adh.130.0133. hdl:10016/34908. ISSN 0066-2062.

- ^ Henry Kamen the war of succession in spain

- ^ Broadberry, Stephen; Esteves, Rui Pedro (2024), Herranz-Loncán, Alfonso; Igual-Luis, David; Vilar, Hermínia Vasconcelos; Freire Costa, Leonor (eds.), "The Iberian Economy in Comparative Perspective, 1800–2000", An Economic History of the Iberian Peninsula, 700–2000, Cambridge University Press, pp. 648–678, doi:10.1017/9781108770217.027, ISBN 978-1-108-48832-7

- ^ Weinstein, J and Imai, K. Measuring the Economic Impact of Civil Wars. (2000)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Solsten, Eric; Meditz, Sandra (1988). Spain: a country study (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Maddison, Angus (2006). The world economy (PDF). Paris, France: Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). pp. 400–600. ISBN 978-92-64-02261-4.

- ^ Leandro Prados de la Escosura: Spanish economic growth in the long run: What historical national accounts show, 2016

- ^ See collectives

- ^ Pegenaute, Luis. "Censoring Translation and Translation as Censorship: Spain under Franco" (PDF). www.arts.kuleuven.be. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Romanos, Eduardo (2014). "Emotions, Moral Batteries and High-Risk Activism: Understanding the Emotional Practices of the Spanish Anarchists under Franco's Dictatorship". Contemporary European History. 23 (4): 545–564. doi:10.1017/S0960777314000319. JSTOR 43299690. S2CID 145621496.

- ^ "Syndicalism and the influence of anarchism in France, Italy and Spain" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ On the historiography see Joseph Harrison, "The Economic History of Spain Since 1800." Economic History Review, 43#1 (1990), pp. 79–89. online

- ^ Leandro Prados De La Escosura, and Joan R. Rosés, "Accounting for growth: Spain, 1850–2019." Journal of Economic Surveys 35.3 (2021): 804-832.

- ^ "OECD Economic Surveys: Spain 1988OECD Economic Surveys: Spain 1988". Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ "Country statistical profiles 2006 (the URL leads directly to information on Spain)". OECD Stat Extracts. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ^ Permanent Lisbon Unit (October 2005), "II. Diagnosis and Challenges of the Spanish Economy" (PDF), in National Coordinator for Lisbon Strategy (ed.), Convergence and Employment: The Spanish National Reform Program, Spanish Prime Minister's Economic Office (OEP), retrieved 1 May 2009

- ^ "Income inequality", The Economist, Economic and Financial Indicators, 30 October 2008, ISSN 0013-0613, OCLC 1081684, retrieved 1 May 2009

- ^ Smith, Charles (2009), "Economic Indicators", in Wankel, Charles (ed.), Encyclopedia of business in today's world, Thousand Oaks, California, United States: SAGE, ISBN 9781412964272, OCLC 251215319

- ^ Login required — Eurostat 2004 GDP figures

- ^ "Spain (Economy section)", The World Factbook, CIA, 23 April 2009,

GDP growth in 2008 was 1.3%, well below the 3% or higher growth the country enjoyed from 1997 through 2007.

- ^ Login required — EMBARGO: Tuesday 21 October - 12

- ^ "Spain's jobless rate soars to 17%", BBC America, Business, BBC News, 24 April 2009, retrieved 2 May 2009

- ^ My Self-Esteem A Mess Is Refrain For Spain's Unemployed, Bloomberg (June 6, 2012)

- ^ Christopher Bjork; Jonathan House; Sara Schaefer Muñoz (25 May 2012). "Spain Pours Billions Into Bank". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ Abiven, Katell (25 May 2012). "Spain's Bankia seeks record bailout of €19 bn". Yahoo! News. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ M. Jiménez (26 May 2012). "Las pérdidas antes de impuestos de Bankia son de 4.300 millones". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ Eurozone agrees to lend Spain up to 100 billion euros, Reuters (June 9, 2012)

- ^ Exclusive: Spain in talks with Eurozone over sovereign aid, Reuters (August 23, 2012)

- ^ Román, David; Neumann, Jeannette (26 March 2015). "Spain's Economy to Grow 2.8% in 2015". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ 20Minutos. "El PIB español cerró 2014 con su primer crecimiento despues de cinco años de recesión". 20minutos.es - Últimas Noticias. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Bolaños, Alejandro (2016-01-29). "Spanish economy grew 3.2% in 2015". El País. ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

- ^ Maqueda, Antonio (2017-01-30). "Spanish economy outperforms expectations to grow 3.2% in 2016". El País. ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

- ^ Megaw, Nicholas (January 30, 2018). "Spanish economy expands 3.1% in 2017". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2022-12-11. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

- ^ Maqueda, Antonio (2017-09-12). "La economía española creció en 2015 y 2016 más de lo calculado hasta ahora". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- ^ "UPDATE 1-Spain unemployment falls end 2017 from year earlier as economy expands". Kitco News. 2018-01-25. Archived from the original on 2020-10-28. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ "Spanish economy shows resilience as exports boom". euronews.com/. 18 December 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Alvarez-Nogal, Carlos and Leandro Prados de la Escosura. "The rise and fall of Spain (1270–1850)." The Economic History Review.

- Bajo-Rubio, Oscar. "Exports and long-run growth: The case of Spain, 1850-2020." Journal of Applied Economics 25.1 (2022): 1314-1337. online

- Campos, Rodolfo G., Iliana Reggio, and Jacopo Timini. "Autarky in Franco's Spain: The costs of a closed economy." Economic History Review (2023). online

- Carrera Pujal, Jaime. Historia de la economía española. 5 vols. Barcelona 1943–47.

- Casares, Gabriel Tortella. The development of modern Spain: an economic history of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Harvard University Press, 2000.)

- Lains, Pedro; Freire Costa, Leonor; Grafe, Regina; Herranz-Loncán, Alfonso; Igual-Luis, David; Pinilla, Vicente; Vilar, Hermínia Vasconcelos, eds. (2024). An Economic History of the Iberian Peninsula, 700–2000. Cambridge University Press.

- Flynn, Dennis O. "Fiscal Crisis and the Decline of Spain (Castile)." Journal of Economic History, 42#1 (1982), pp. 139–47. online

- Hamilton, Earl J. American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, 1501-1650. 1934, rpt. edn. New York 1965.

- Harrison, Joseph. An economic history of modern Spain (Manchester University Press, 1978)

- Herranz-Loncán, Alfonso. "Railroad Impact in Backward Economies: Spain, 1850-1913," Journal of Economic History (2006) 66#4 pp. 853-881 in JSTOR

- Herranz-Loncán, Alfonso. "Infrastructure investment and Spanish economic growth, 1850–1935." Explorations in Economic History 44.3 (2007): 452-468. online

- Kamen, Henry. "The decline of Castile: the last crisis." Economic History Review 17.1 (1964): 63-76 online.

- Klein, Julius. The Mesta: a study in Spanish economic history, 1273-1836 (Harvard University Press, 1920) online free

- Milward, Alan S. and S. B. Saul. The Development of the Economies of Continental Europe: 1850-1914 (1977) pp 215-270

- Milward, Alan S. and S. B. Saul. The Economic Development of Continental Europe 1780-1870 (2nd ed. 1979), 552pp

- Phillips, Carla Rahn. "Time and Duration: A Model for the Economy of Early Modern Spain". American Historical Review vol 92, No. 3 (June 1987) pp. 531-562.

- Prados De La Escosura, Leandro, and Joan R. Rosés. "Accounting for growth: Spain, 1850–2019." Journal of Economic Surveys 35.3 (2021): 804-832. online

- Del Río, Fernando, and Francisco-Xavier Lores. "Appendix for'Accounting for Spanish Economic Development 1850-2019'." Available at SSRN 4326981 (2023).

- Prados de la Escosura, Leandro (2017), Spanish Economic Growth, 1850 – 2015. Palgrave Macmillan

- Prados de la Escosura, Leandro. "Spain's international position, 1850-1913." Revista de Historia Económica 28.1 (2010): 173+

- Prados de la Escosura, Leandro (2024) A Millennial View of Spain's Development. Springer

- Prados de la Escosura, Leandro, and Joan R. Rosés. "Proximate causes of economic growth in Spain, 1850-2000." (2008). online[permanent dead link]

- Sudrià, Carles. 2021. "A hidden fight behind neutrality. Spain's struggle on exchange rates and gold during the Great War." European Review of Economic History.

- Vicens Vives, Jaime; Jorge Nadal Oller, and Frances M. López-Morillas. An Economic History of Spain (Vol. 1. Princeton University Press, 1969)

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

KSF

KSF