Economic reforms and recovery proposals regarding the eurozone crisis

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

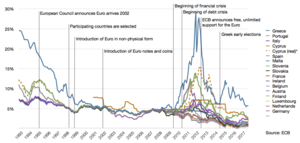

The eurozone crisis, also known as the European sovereign-debt crisis, was a financial crisis that made it difficult or impossible for some countries in the euro area to repay or re-finance their government debt.

The European sovereign debt crisis resulted from a combination of complex factors, including the globalization of finance; easy credit conditions during the 2002–2008 period that encouraged high-risk lending and borrowing practices; the 2007–2008 financial crisis; international trade imbalances; real-estate bubbles that have since burst; the 2008–2012 global recession; fiscal policy choices related to government revenues and expenses; and approaches used by nations to bail out troubled banking industries and private bondholders, assuming private debt burdens or socializing losses. [1][2]

One narrative describing the causes of the crisis begins with the significant increase in savings available for investment during the 2000–2007 period when the global pool of fixed-income securities increased from approximately $36 trillion in 2000 to $70 trillion by 2007. This "Giant Pool of Money" increased as savings from high-growth developing nations entered global capital markets. Investors searching for higher yields than those offered by U.S. Treasury bonds sought alternatives globally.[3]

The temptation offered by such readily available savings overwhelmed the policy and regulatory control mechanisms in country after country, as lenders and borrowers put these savings to use, generating bubble after bubble across the globe. While these bubbles have burst, causing asset prices (e.g., housing and commercial property) to decline, the liabilities owed to global investors remain at full price, generating questions regarding the solvency of governments and their banking systems.[1]

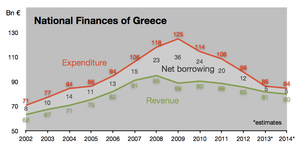

How each European country involved in this crisis borrowed and invested the money varies. For example, Ireland's banks lent the money to property developers, generating a massive property bubble. When the bubble burst, Ireland's government and taxpayers assumed private debts. In Greece, the government increased its commitments to public workers in the form of extremely generous wage and pension benefits, with the former doubling in real terms over 10 years.[4] Iceland's banking system grew enormously, creating debts to global investors (external debts) several times GDP.[1][5]

The interconnection in the global financial system means that if one nation defaults on its sovereign debt or enters into recession putting some of the external private debt at risk, the banking systems of creditor nations face losses. For example, in October 2011, Italian borrowers owed French banks $366 billion (net). Should Italy be unable to finance itself, the French banking system and economy could come under significant pressure, which in turn would affect France's creditors and so on. This is referred to as financial contagion.[6][7] Another factor contributing to interconnection is the concept of debt protection. Institutions entered into contracts called credit default swaps (CDS) that result in payment should default occur on a particular debt instrument (including government issued bonds). But, since multiple CDSs can be purchased on the same security, it is unclear what exposure each country's banking system now has to CDS.[8]

Greece hid its growing debt and deceived EU officials with the help of derivatives designed by major banks.[9][10][11][12][13][14] Although some financial institutions clearly profited from the growing Greek government debt in the short run,[9] there was a long lead-up to the crisis.

Direct loans to banks and banking regulation

[edit]On 28 June 2012 Eurozone leaders agreed to permit loans by the European Stability Mechanism to be made directly to stressed banks rather than through Eurozone states, to avoid adding to sovereign debt. The reform was linked to plans for banking regulation by the European Central Bank. The reform was immediately reflected by a reduction in yield of long-term bonds issued by member states such as Italy and Spain and a rise in value of the Euro.[15][16][17]

Less austerity, more investment

[edit]There has been substantial criticism over the austerity measures implemented by most European nations to counter this debt crisis. US economist and Nobel laureate Paul Krugman argues that an abrupt return to "'non-Keynesian' financial policies" is not a viable solution[18] Pointing at historical evidence, he predicts that deflationary policies now being imposed on countries such as Greece and Spain will prolong and deepen their recessions.[19] Together with over 9,000 signatories of "A Manifesto for Economic Sense"[20] Krugman also dismissed the belief of austerity focusing policy makers such as EU economic commissioner Olli Rehn and most European finance ministers[21] that "budget consolidation" revives confidence in financial markets over the longer haul.[22][23] In a 2003 study that analyzed 133 IMF austerity programmes, the IMF's independent evaluation office found that policy makers consistently underestimated the disastrous effects of rigid spending cuts on economic growth.[24][25] In early 2012 an IMF official, who negotiated Greek austerity measures, admitted that spending cuts were harming Greece.[26] In October 2012, the IMF said that its forecasts for countries which implemented austerity programs have been consistently overoptimistic, suggesting that tax hikes and spending cuts have been doing more damage than expected, and countries which implemented fiscal stimulus, such as Germany and Austria, did better than expected.[27]

According to Keynesian economists "growth-friendly austerity" relies on the false argument that public cuts would be compensated for by more spending from consumers and businesses, a theoretical claim that has not materialized.[28] The case of Greece shows that excessive levels of private indebtedness and a collapse of public confidence (over 90% of Greeks fear unemployment, poverty and the closure of businesses)[29] led the private sector to decrease spending in an attempt to save up for rainy days ahead. This led to even lower demand for both products and labor, which further deepened the recession and made it ever more difficult to generate tax revenues and fight public indebtedness.[30] According to Financial Times chief economics commentator Martin Wolf, "structural tightening does deliver actual tightening. But its impact is much less than one to one. A one percentage point reduction in the structural deficit delivers a 0.67 percentage point improvement in the actual fiscal deficit." This means that Ireland e.g. would require structural fiscal tightening of more than 12% to eliminate its 2012 actual fiscal deficit, a task that is difficult to achieve without an exogenous eurozone-wide economic boom.[31] Austerity is bound to fail if it relies largely on tax increases[32] instead of cuts in government expenditures coupled with encouraging "private investment and risk-taking, labor mobility and flexibility, an end to price controls, tax rates that encouraged capital formation ..." as Germany has done in the decade before the crisis.[33] According to the Europlus Monitor Report 2012, no country should tighten its fiscal reins by more than 2% of GDP in one year, in order to avoid recession.[34]

Instead of public austerity, a "growth compact" centering on tax increases[30] and deficit spending is proposed. Since struggling European countries lack the funds to engage in deficit spending, German economist and member of the German Council of Economic Experts Peter Bofinger and Sony Kapoor of the global think tank Re-Define suggest providing €40 billion in additional funds to the European Investment Bank (EIB), which could then lend ten times that amount to the employment-intensive smaller business sector.[30] The EU is currently planning a possible €10 billion increase in the EIB's capital base. Furthermore, the two suggest financing additional public investments by growth-friendly taxes on "property, land, wealth, carbon emissions and the under-taxed financial sector". They also called on EU countries to renegotiate the EU savings tax directive and to sign an agreement to help each other crack down on tax evasion and avoidance. Currently authorities capture less than 1% in annual tax revenue on untaxed wealth transferred between EU members.[30] According to the Tax Justice Network, worldwide, a global super-rich elite had between $21 and $32 trillion (up to 26,000bn Euros) hidden in secret tax havens by the end of 2010, resulting in a tax deficit of up to $280bn.[35][36]

Apart from arguments over whether or not austerity, rather than increased or frozen spending, is a macroeconomic solution,[37] union leaders have also argued that the working population is being unjustly held responsible for the economic mismanagement errors of economists, investors, and bankers. Over 23 million EU workers have become unemployed as a consequence of the global economic crisis of 2007–2010, and this has led many to call for additional regulation of the banking sector across not only Europe, but the entire world.[38]

In the turmoil of the 2007–2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession, the focus across all EU member states was to gradually to implement austerity measures, with the purpose of lowering budget deficits to levels below 3% of GDP, so that the debt level would either stay below -or start decline towards- the 60% limit defined by the Stability and Growth Pact. In order to further restore the confidence in Europe, 23 out of 27 EU countries also agreed on adopting the Euro Plus Pact, consisting of political reforms to improve fiscal strength and competitiveness; and 25 out of 27 EU countries also decided to implement the Fiscal Compact which include the commitment of each participating country to introduce a balanced budget amendment as part of their national law/constitution. The Fiscal Compact is a direct successor of the previous Stability and Growth Pact, but it is more strict, not only because criteria compliance will be secured through its integration into national law/constitution, but also because it starting from 2014 will require all ratifying countries not involved in ongoing bailout programmes, to comply with the new strict criteria of only having a structural deficit of either maximum 0.5% or 1% (depending on the debt level).[39][40] Each of the eurozone countries being involved in a bailout program (Greece, Portugal and Ireland) was asked both to follow a program with fiscal consolidation/austerity, and to restore competitiveness through implementation of structural reforms and internal devaluation, i.e. lowering their relative production costs.[41] The measures implemented to restore competitiveness in the weakest countries are needed, not only to build the foundation for GDP growth, but also in order to decrease the current account imbalances among eurozone member states.[42][43]

It has been a long-known belief that austerity measures will always reduce the GDP growth in the short term. The reason why Europe nevertheless chose the path of austerity measures, is because they on the medium and long term have been found to benefit and prosper GDP growth, as countries with healthy debt levels in return will be rewarded by the financial markets with higher confidence and lower interest rates. Some economists believing in Keynesian policies, however criticized the timing and amount of austerity measures being called for in the bailout programmes, as they argued such extensive measures should not be implemented during the crisis years with an ongoing recession, but if possible delayed until the years after some positive real GDP growth had returned. In October 2012, a report published by International Monetary Fund (IMF) also found, that tax hikes and spending cuts during the most recent decade had indeed damaged the GDP growth more severely, compared to what had been expected and forecasted in advance (based on the "GDP damage ratios" previously recorded in earlier decades and under different economic scenarios).[27] Already a half-year earlier, several European countries as a response to the problem with subdued GDP growth in the eurozone, likewise had called for the implementation of a new reinforced growth strategy based on additional public investments, to be financed by growth-friendly taxes on property, land, wealth, and financial institutions. In June 2012, EU leaders agreed as a first step to moderately increase the funds of the European Investment Bank, in order to kick-start infrastructure projects and increase loans to the private sector. A few months later 11 out of 17 eurozone countries also agreed to introduce a new EU financial transaction tax to be collected from 1 January 2014.[44]

Progress

[edit]In April 2012, Olli Rehn, the European commissioner for economic and monetary affairs in Brussels, "enthusiastically announced to EU parliamentarians in mid-April that 'there was a breakthrough before Easter'. He said the European heads of state had given the green light to pilot projects worth billions, such as building highways in Greece." Other growth initiatives include "project bonds" wherein the EIB would "provide guarantees that safeguard private investors. In the pilot phase until 2013, EU funds amounting to €230 million are expected to mobilize investments of up to €4.6 billion." Der Spiegel also said: "According to sources inside the German government, instead of funding new highways, Berlin is interested in supporting innovation and programs to promote small and medium-sized businesses. To ensure that this is done as professionally as possible, the Germans would like to see the southern European countries receive their own state-owned development banks, modeled after Germany's [Marshall Plan-era-origin] Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) banking group. It's hoped that this will get the economy moving in Greece and Portugal."[45]

Increase competitiveness

[edit]Crisis countries must significantly increase their international competitiveness to generate economic growth and improve their terms of trade. Indian-American journalist Fareed Zakaria notes in November 2011 that no debt restructuring will work without growth, even more so as European countries "face pressures from three fronts: demography (an aging population), technology (which has allowed companies to do much more with fewer people) and globalization (which has allowed manufacturing and services to locate across the world)."[46]

In case of economic shocks, policy makers typically try to improve competitiveness by external devaluation, as in the case of Iceland, which suffered from the 2008–2012 Icelandic financial crisis but has since vastly improved its position. However, eurozone countries cannot devalue their currency.

Internal devaluation

[edit]

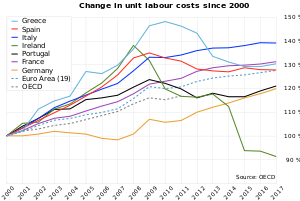

As a workaround many policy makers try to restore competitiveness through internal devaluation, a painful economic adjustment process, where a country aims to reduce its unit labour costs.[41][47] German economist Hans-Werner Sinn noted in 2012 that Ireland was the only country that had implemented relative wage moderation in the last five years, which helped decrease its relative price/wage levels by 16%. Greece would need to bring this figure down by 31%, effectively reaching the level of Turkey.[48][49] By 2012, wages in Greece have been cut to a level last seen in the late 1990s. Purchasing power dropped even more to the level of 1986.[50]

Other economists argue that no matter how much Greece and Portugal drive down their wages, they could never compete with low-cost developing countries such as China or India. Instead weak European countries must shift their economies to higher quality products and services, though this is a long-term process and may not bring immediate relief.[51]

Fiscal devaluation

[edit]Another option would be to implement fiscal devaluation, based on an idea originally developed by John Maynard Keynes in 1931.[52][53] According to this neo-Keynesian logic, policy makers can increase the competitiveness of an economy by lowering corporate tax burden such as employer's social security contributions, while offsetting the loss of government revenues through higher taxes on consumption (VAT) and pollution, i.e. by pursuing an ecological tax reform.[54][55][56]

Germany has successfully pushed its economic competitiveness by increasing the value added tax (VAT) by three percentage points in 2007, and using part of the additional revenues to lower employer's unemployment insurance contribution. Portugal has taken a similar stance[56] and also France appears to follow this suit. In November 2012 French president François Hollande announced plans to reduce tax burden of the corporate sector by €20 billion within three years, while increasing the standard VAT from 19.6% to 20% and introducing additional eco-taxes in 2016. To minimize negative effects of such policies on purchasing power and economic activity the French government will partly offset the tax hikes by decreasing employees' social security contributions by €10 billion and by reducing the lower VAT for convenience goods (necessities) from 5.5% to 5%.[57]

Progress

[edit]

On 15 November 2011, the Lisbon Council published the Euro Plus Monitor 2011. According to the report most critical eurozone member countries are in the process of rapid reforms.[58] The authors note that "Many of those countries most in need to adjust [...] are now making the greatest progress towards restoring their fiscal balance and external competitiveness". Greece, Ireland and Spain are among the top five reformers and Portugal is ranked seventh among 17 countries included in the report (see graph).[59]

In its latest Euro Plus Monitor Report 2012, published in November 2012, the Lisbon Council finds that the eurozone has slightly improved its overall health. With the exception of Greece, all eurozone crisis countries are either close to the point where they have achieved the major adjustment or are likely to get there over the course of 2013. Portugal and Italy are expected to progress to the turnaround stage in spring 2013, possibly followed by Spain in autumn, while the fate of Greece continues to hang in the balance. Overall, the authors suggest that if the eurozone gets through the current acute crisis and stays on the reform path "it could eventually emerge from the crisis as the most dynamic of the major Western economies".[34]

Address current account imbalances

[edit]

Regardless of the corrective measures chosen to solve the current predicament, as long as cross border capital flows remain unregulated in the euro area,[60] current account imbalances are likely to continue. A country that runs a large current account or trade deficit (i.e., importing more than it exports) must ultimately be a net importer of capital; this is a mathematical identity called the balance of payments. In other words, a country that imports more than it exports must either decrease its savings reserves or borrow to pay for those imports. Conversely, Germany's large trade surplus (net export position) means that it must either increase its savings reserves or be a net exporter of capital, lending money to other countries to allow them to buy German goods.[61]

The 2009 trade deficits for Italy, Spain, Greece, and Portugal were estimated to be $42.96 billion, $75.31bn and $35.97bn, and $25.6bn respectively, while Germany's trade surplus was $188.6bn.[62] A similar imbalance exists in the U.S., which runs a large trade deficit (net import position) and therefore is a net borrower of capital from abroad. Ben Bernanke warned of the risks of such imbalances in 2005, arguing that a "savings glut" in one country with a trade surplus can drive capital into other countries with trade deficits, artificially lowering interest rates and creating asset bubbles.[63][64][65]

A country with a large trade surplus would generally see the value of its currency appreciate relative to other currencies, which would reduce the imbalance as the relative price of its exports increases. This currency appreciation occurs as the importing country sells its currency to buy the exporting country's currency used to purchase the goods. Alternatively, trade imbalances can be reduced if a country encouraged domestic saving by restricting or penalizing the flow of capital across borders, or by raising interest rates, although this benefit is likely offset by slowing down the economy and increasing government interest payments.[66]

Either way, many of the countries involved in the crisis are on the euro, so devaluation, individual interest rates and capital controls are not available. The only solution left to raise a country's level of saving is to reduce budget deficits and to change consumption and savings habits. For example, if a country's citizens saved more instead of consuming imports, this would reduce its trade deficit.[66] It has therefore been suggested that countries with large trade deficits (e.g. Greece) consume less and improve their exporting industries. On the other hand, export driven countries with a large trade surplus, such as Germany, Austria and the Netherlands would need to shift their economies more towards domestic services and increase wages to support domestic consumption.[67][68]

Progress

[edit]In its spring 2012 economic forecast, the European Commission finds "some evidence that the current-account rebalancing is underpinned by changes in relative prices and competitiveness positions as well as gains in export market shares and expenditure switching in deficit countries."[69] In May 2012 German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble has signaled support for a significant increase in German wages to help decrease current account imbalances within the eurozone.[70]

Mobilization of credit

[edit]A number of proposals were made in the summer of 2012 to purchase the debt of distressed European countries such as Spain and Italy. Markus Brunnermeier,[71] the economist Graham Bishop, and Daniel Gros were among those advancing proposals. Finding a formula which was not simply backed by Germany is central in crafting an acceptable and effective remedy.[72]

Commentary

[edit]US President Barack Obama stated in June 2012: "Right now, [Europe's] focus has to be on strengthening their overall banking system...making a series of decisive actions that give people confidence that the banking system is solid...In addition, they’re going to have to look at how do they achieve growth at the same time as they’re carrying out structural reforms that may take two or three or five years to fully accomplish. So countries like Spain and Italy, for example, have embarked on some smart structural reforms that everybody thinks are necessary – everything from tax collection to labor markets to a whole host of different issues. But they've got to have the time and the space for those steps to succeed. And if they are just cutting and cutting and cutting, and their unemployment rate is going up and up and up, and people are pulling back further from spending money because they're feeling a lot of pressure – that can make it harder for them to carry out some of these reforms over the long term...[I]n addition to sensible ways to deal with debt and government finances, there's a parallel discussion that's taking place among European leaders to figure out how do we also encourage growth and show some flexibility to allow some of these reforms to really take root."[73]

The Economist wrote in June 2012: "Outside Germany, a consensus has developed on what Mrs. Merkel must do to preserve the single currency. It includes shifting from austerity to a far greater focus on economic growth; complementing the single currency with a banking union (with euro-wide deposit insurance, bank oversight and joint means for the recapitalization or resolution of failing banks); and embracing a limited form of debt mutualization to create a joint safe asset and allow peripheral economies the room gradually to reduce their debt burdens. This is the refrain from Washington, Beijing, London and indeed most of the capitals of the euro zone. Why hasn’t the continent’s canniest politician sprung into action?"[74]

See also

[edit]- 2000s commodities boom

- 2007–2008 financial crisis

- 2008–2012 Icelandic financial crisis

- Crisis situations and protests in Europe since 2000

- European sovereign-debt crisis: List of acronyms

- European sovereign-debt crisis: List of protagonists

- Federal Reserve Economic Data FRED

- Great Recession

- List of countries by credit rating

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Lewis, Michael (2011). Boomerang: Travels in the New Third World. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-08181-7.

- ^ Lewis, Michael (26 September 2011). "Touring the Ruins of the Old Economy". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ "NPR-The Giant Pool of Money-May 2008". Thisamericanlife.org. 9 May 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Heard on Fresh Air from WHYY (4 October 2011). "Michael Lewis-How the Financial Crisis Created a New Third World-October 2011". NPR. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Lewis, Michael (April 2009). "Wall Street on the Tundra". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

In the end, Icelanders amassed debts amounting to 850 percent of their G.D.P. (The debt-drowned United States has reached just 350 percent.)

- ^ Feaster, Seth W.; Schwartz, Nelson D.; Kuntz, Tom (22 October 2011). "NYT-It's All Connected-A Spectators Guide to the Euro Crisis". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ XAQUÍN, G.V.; McLean, Alan; Tse, Archie (22 October 2011). "NYT-It's All Connected-An Overview of the Euro Crisis-October 2011". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ "The Economist-No Big Bazooka-29 October 2011". Economist. 29 October 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ a b Story, Louise; Landon Thomas Jr; Schwartz, Nelson D. (14 February 2010). "Wall St. Helped to Mask Debt Fueling Europe's Crisis". The New York Times. New York. pp. A1. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ "Merkel Slams Euro Speculation, Warns of 'Resentment' (Update 1)". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Knight, Laurence (22 December 2010). "Europe's Eastern Periphery". BBC. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "PIIGS Definition". investopedia.com. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Riegert, Bernd. "Europe's next bankruptcy candidates?". dw-world.com. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Philippas, Nikolaos D. Ζωώδη Ένστικτα και Οικονομικές Καταστροφές (in Greek). skai.gr. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Erlanger, Steven; Geitner, Paul (29 June 2012). "Europeans Agree to Use Bailout Fund to Aid Banks". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ "EURO AREA SUMMIT STATEMENT" (PDF). Brussels: European Union. 29 June 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

We affirm that it is imperative to break the vicious circle between banks and sovereigns. The Commission will present Proposals on the basis of Article 127(6) for a single supervisory mechanism shortly. We ask the Council to consider these Proposals as a matter of urgency by the end of 2012. When an effective single supervisory mechanism is established, involving the ECB, for banks in the euro area the ESM could, following a regular decision, have the possibility to recapitalize banks directly.

- ^ Davies, Gavyn (29 June 2012). "More questions than answers after the summit" (blog by expert). Financial Times. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ Kaletsky, Anatole (6 February 2012). "The Greek Vise". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ Kaletsky, Anatole (11 February 2010). "'Greek tragedy won't end in the euro's death'". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ "Signatories". Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ Briançon, Pierre (11 October 2012). "Europe must realize austerity doesn't work". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ Spiegel, Peter (7 November 2012). "EU hits back at IMF over austerity". Financial Times. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ Krugman, Paul; Layard, Richard (27 June 2012). "A manifesto for economic sense". Financial Times. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ International Monetary Fund: Independent Evaluation Office, Fiscal Adjustment in IMF-supported Programs (Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund, 2003); see for example page vii.

- ^ Lindner, Fabian (18 February 2012). "Europe is in dire need of lazy spendthrifts". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ^ Smith, Helena (1 February 2012). "IMF official admits: austerity is harming Greece". The Guardian. Athens. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ a b Brad Plumer (12 October 2012) "IMF: Austerity is much worse for the economy than we thought" Archived 11 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Washington Post

- ^ "Investment (% of GDP)". Google/IMF. 9 October 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ "Μνημόνιο ένα χρόνο μετά: Αποδοκιμασία, αγανάκτηση, απαξίωση, ανασφάλεια (One Year after the Memorandum: Disapproval, Anger, Disdain, Insecurity)". skai.gr. 18 May 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d Kapoor, Sony, and Peter Bofinger: "Europe can't cut and grow", The Guardian, 6 February 2012.

- ^ Wolf, Martin (1 May 2012). "Does austerity lower deficits in the eurozone?". The New York Times. London. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ de Rugy, Veronique (10 May 2012). "Two kinds of austerity". The Washington Examiner. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ "Europe's Phony Growth Debate: The austerity vs. spending fight ignores essential reforms". The Wall Street Journal. 24 April 2012.

- ^ a b c "Euro Plus Monitor 2012". The Lisbon Council. 29 November 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ "Bis zu 26 Billionen in Steueroasen gebunkert". Der Standard (in German). Vienna. Reuters. 22 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ "'Tax havens: Super-rich 'hiding' at least $21tn'". BBC News. London. 22 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Vendola, Nichi, "Italian debt: Austerity economics? That's dead wrong for us", The Guardian, 13 July 2011.

- ^ "European cities hit by anti-austerity protests". BBC News. 29 September 2010.

- ^ Pidd, Helen (2 December 2011). "Angela Merkel vows to create 'fiscal union' across eurozone". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "European fiscal union: what the experts say". The Guardian. London. 2 December 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ a b Krugman, Paul (22 October 2011). "European Wage Update". NYT. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ "Current account balance (%)". Google/IMF. 9 October 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ "Current account balance (%) and Current account balance (US$) (animation)". Google/IMF. 9 October 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ "Eleven euro states back financial transaction tax". Reuters. 9 October 2012. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Böll, Sven, et al., (trans. Paul Cohen), "Austerity Backlash: What Merkel's Isolation Means For the Euro Crisis", Der Spielgel, 05/01/2012. Retrieved 2012-05-01.

- ^ "CNN Fareed Zakaria GPS-10 November 2011". CNN. 10 November 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Buckley, Neil (28 June 2012). "Myths and truths of the Baltic austerity model". Financial Times.

- ^ "Wir sitzen in der Falle". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. 18 February 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ "Labour cost index – recent trends". Eurostat Wiki. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ "Griechenland: "Mittelstand vom Verschwinden bedroht"". DiePresse. 19 November 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Do some countries in the Eurozone need an internal devaluation? A reassessment of what unit labour costs really mean". Vox EU. 31 March 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Keynes, J M , (1931), Addendum to: Great Britain. Committee on Finance and Industry Report [Macmillan Report] (London:His Majesty ́s Stationery Office, 1931) 190–209. Reprinted in Donald Moggridge, The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 20 (London: Macmillan and Cambridge: Cambridge Press for the Royal Economic Society, 1981), 283–309.

- ^ Keynes, John Maynard (1998). The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes (30 Volume Hardback). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30766-6.

- ^ Aghion, Philippe; Cette, Gilbert; Farhi, Emmanuel; Cohen, Elie (24 October 2012). "Pour une dévaluation fiscale". Le Monde.

- ^ Farhi, Emmanuel; Gopinath, Gita; Itskhoki, Oleg (18 October 2012). "Fiscal Devaluations (Federal Reserve Bank Boston Working Paper No. 12-10)" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ a b Correia, Isabel Horta (Winter 2011). "Fiscal Devaluation (Economic Bulletin and Financial Stability Report Articles" (PDF). Banco de Portugal. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ Braunberger, Gerald (4 November 2012). "Man braucht keine eigene Währung, um abzuwerten. Die Finanzpolitik kann es auch. Aus aktuellem Anlass: Das Konzept der fiskalischen Abwertung". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ EU austerity drive country by country, BBC (21 May 2012)

- ^ "Euro Plus Monitor 2011". The Lisbon Council. 15 November 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ Grabel, Ilene (1 May 1998). "Foreign Policy in Focus , Portfolio Investment". Fpif.org. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ Pearlstein, Steven (21 May 2010). "Forget Greece: Europe's real problem is Germany". The Washington Post.

- ^ "CIA Factbook-Data". Cia.gov. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "Ben Bernanke-U.S. Federal Reserve-The Global Savings Glut and U.S. Current Account Balance-March 2005". Federal Reserve. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (2 March 2009). "Revenge of the Glut". The New York Times.

- ^ "P2P Foundation » Blog Archive » Defending Greece against failed neoliberal policies through the creation of sovereign debt for the productive economy". Blog.p2pfoundation.net. 6 February 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ a b Krugman, Paul (7 September 1998). "Saving Asia: It's Time To Get Radical". CNN.

- ^ Wolf, Martin (6 December 2011). "Merkozy failed to save the eurozone". Financial Times. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ^ Hagelüken, Alexander (8 December 2012). "Starker Mann, was nun?". Süddeutsche Zeitung.

- ^ "European economic forecast – spring 2012". European Commission. 1 May 2012. p. 38. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Schäuble findet deutliche Lohnerhöhungen berechtigt". Süddeutsche Zeitung. 5 May 2012.

- ^ "European Safe Bonds". Euro-nomics.

- ^ Thomas, Landon Jr. (31 July 2012). "Economic Thinkers Try to Solve the Euro Puzzle". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ President Obama-Remarks by the President-June 2012

- ^ The Economist-Start the Engines, Angela-June 2012

External links

[edit]- The EU Crisis Pocket Guide by the Transnational Institute in English (2012) – Italian (2012) – Spanish (2011)

- 2011 Dahrendorf Symposium – Changing the Debate on Europe – Moving Beyond Conventional Wisdoms

- Eurostat – Statistics Explained: Structure of government debt (October 2011 data)

KSF

KSF