Edward Thomas (poet)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

Phillip Edward Thomas | |

|---|---|

Thomas in 1905 | |

| Born | 3 March 1878 Lambeth, Surrey, England |

| Died | 9 April 1917 (aged 39) Arras, Pas-de-Calais, France |

| Pen name | Edward Thomas, Edward Eastaway |

| Occupation |

|

| Genre | Nature poetry, war poetry |

| Subject | Nature, war |

| Spouse |

Helen Noble (m. 1899) |

| Children | 3 |

Philip Edward Thomas (3 March 1878 – 9 April 1917) was a British writer of poetry and prose. He is sometimes considered a war poet, although few of his poems deal directly with his war experiences. He only started writing poetry at the age of 36, but by that time he had already been a prolific critic, biographer, nature writer and travel writer for two decades. In 1915, he enlisted in the British Army to fight in the First World War and was killed in action during the Battle of Arras in 1917, soon after he arrived in France.

Life and career as a soldier

[edit]Background and early life

[edit]

Edward Thomas was the son of Mary Elizabeth Townsend and Philip Henry Thomas, a civil servant, author, preacher and local politician.[1] He was born in Lambeth, an area of present-day south London, previously in Surrey.[2] He was educated at Belleville School, Battersea Grammar School and St Paul's School, all in London.

Thomas's family were mostly Welsh.[3] Of his six great-grandparents for whom information has been found, five were born in Wales, and one in Ilfracombe.[4] All four of his grandparents had been born and brought up in Wales. Of these, his paternal grandparents lived in Tredegar. His grandmother, Rachel Phillips, had been born and brought up there, whilst his grandfather, Henry Thomas, who'd been born in Neath, worked there as a collier and then an engine fitter. Their son, Philip Henry, who was Edward Thomas's father, had been born in Tredegar and spent his early years there.[5]

Thomas's maternal grandfather was Edward Thomas Townsend, the son of Margaret and Alderman William Townsend, a Newport merchant active in Liberal and Chartist politics. His maternal grandmother was Catherine Marendaz, from Margam, just outside Port Talbot, where her family had been tenant farmers since at least the late 1790s. Their daughter, Mary Elizabeth Townsend, married Philip Henry Thomas. Mary and Philip were Edward Thomas's parents.[6]

Although Edward Thomas's father, Philip Henry Thomas, had left Tredegar for Swindon (and then London) in his early teens, “the Welsh connection was … enduring.”[7] He continued throughout his life to visit his relatives in south Wales. His feelings for Wales were also manifest in other ways. There were frequent journeys to Merthyr to lecture on behalf of the Ethical Society, and even a visit in 1906 to a National Eisteddfod in north Wales. Philip Henry Thomas “cultivated his Welsh connections assiduously,” so much so that Edward Thomas and his brothers could even boast that their father knew Lloyd George.[8]

Like his father before him, Edward Thomas continued throughout his life[9] to visit his many relatives and friends in Ammanford, Newport, Swansea and Pontardulais.[10] Thomas also enjoyed a twenty-year friendship with a distant cousin, the teacher, theologian and poet, John Jenkins (Gwili), of the Hendy, just across the county border from Pontardulais.[11] Gwili’s elegy for Thomas describes the many walks they took together in the countryside around Pontardulais and Ammanford.[12] Such was the family’s connection to this part of Wales that three of Edward Thomas's brothers were sent to school at Watcyn Wyn’s Academy in Ammanford, where Gwili had become headmaster in 1908.[13]

From Oxford to Adlestrop

[edit]

Between 1898 and 1900, Thomas was a history scholar at Lincoln College, Oxford.[14] In June 1899, he married Helen Berenice Noble (1877–1967)[15][16] in Fulham, while still an undergraduate, and determined to live his life by the pen. He then worked as a book reviewer, reviewing up to 15 books every week.[17] He was already a seasoned writer by the outbreak of war, having published widely as a literary critic and biographer as well as writing about the countryside. He also wrote a novel, The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans (1913), a "book of delightful disorder".[18]

Thomas worked as literary critic for the Daily Chronicle in London and became a close friend of Welsh tramp poet W. H. Davies, whose career he almost single-handedly developed.[19] From 1905 until 1906, Thomas lived with his wife Helen and their two children at Elses Farm near Sevenoaks, Kent. He rented a tiny cottage nearby to Davies, and nurtured his writing as best he could. On one occasion, Thomas arranged for the manufacture, by a local wheelwright, of a makeshift wooden leg for Davies.

In 1906 the family moved to Steep, East Hampshire, on the outskirts of the market town of Petersfield - attracted by the landscape, its links with London, and schooling at the innovative co-educational private school Bedales. They lived in and around Steep in three separate homes for ten years until 1916 when they moved to Essex following Thomas's enlistment. Their third child, Myfanwy, was born in August 1910.[20]

Even though Thomas thought that poetry was the highest form of literature and regularly reviewed it, he only became a poet himself at the end of 1914[17] when living at Steep, and initially published his poetry under the name Edward Eastaway. The American poet Robert Frost, who was living in England at the time, in particular encouraged Thomas (then more famous as a critic) to write poetry, and their friendship was so close that the two planned to reside side by side in the United States.[21] Frost's most famous poem, "The Road Not Taken", was inspired by walks with Thomas and Thomas's indecisiveness about which route to take.

By August 1914, the village of Dymock in Gloucestershire had become the residence of a number of literary figures, including Lascelles Abercrombie, Wilfrid Gibson and Robert Frost. Edward Thomas was a visitor at this time.[22]

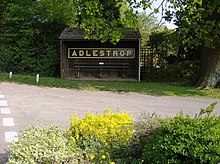

Thomas immortalised the (now-abandoned) railway station at Adlestrop in a poem of that name after his train made a stop at the Cotswolds station on 24 June 1914, shortly before the outbreak of the First World War.[23]

War service

[edit]

Thomas enlisted in the Artists Rifles in July 1915, despite being a mature married man who could have avoided enlisting. He was unintentionally influenced in this decision by his friend Frost, who had returned to the U.S. but sent Thomas an advance copy of "The Road Not Taken".[24] The poem was intended by Frost as a gentle mocking of indecision, particularly the indecision that Thomas had shown on their many walks together; however, most took the poem more seriously than Frost intended, and Thomas similarly took it seriously and personally, and it provided the last straw in Thomas's decision to enlist.[24]

Thomas's training was at a temporary army camp at High Beach in Epping Forest.[25] Despite the squalid conditions in the camp, he enjoyed the forest and in the following year moved with his family to a nearby cottage. One of his last poems, "Out in the dark", was written at High Beach at Christmas 1916.[26]

Thomas was promoted to corporal, and in November 1916 was commissioned into the Royal Garrison Artillery as a second lieutenant. He was killed in action soon after he arrived in France at Arras on Easter Monday, 9 April 1917. To spare the feelings of his widow Helen, she was told the fiction of a "bloodless death" i.e. that Thomas was killed by the concussive blast wave of one of the last shells fired as he stood to light his pipe and that there was no mark on his body.[27] However, a letter from his commanding officer Franklin Lushington written in 1936 (and discovered many years later in an American archive) states that in reality the cause of Thomas's death was being "shot clean through the chest".[28] W. H. Davies was devastated by the death and his commemorative poem "Killed in Action (Edward Thomas)" was included in Davies's 1918 collection "Raptures".[19]

Thomas is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery at Agny in France (Row C, Grave 43).[29]

Personal life

[edit]Thomas and his wife Helen had three children: a son, Merfyn, and daughters Bronwen and Myfanwy. After the war, Helen wrote about her courtship and early married life with Edward in the autobiography As it Was (1926); a second volume, World Without End was published in 1931. Myfanwy later said that the books had been written by her mother as a form of therapy to help lift herself from the deep depression into which she had fallen following Thomas's death.[30]

Helen's short memoir A Memory of W. H. Davies was published in 1973, after her own death. In 1988, Helen's writings were gathered into a book published under the title Under Storm's Wing, which included As It Was and World Without End as well as a selection of other short works by Helen and her daughter Myfanwy and six letters sent by Robert Frost to her husband.[31] Myfanwy Thomas, only six when her father died, produced her own memoir of Edward and Helen, One of These Fine Days, in 1982.[32]

Poetry

[edit]In Memoriam

The flowers left thick at nightfall in the wood

This Eastertide call into mind the men,

Now far from home, who, with their sweethearts, should

Have gathered them and will do never again.

Thomas's poems are written in a colloquial style and frequently feature the English countryside. The short poem In Memoriam exemplifies how his poetry blends the themes of war and the countryside. On 11 November 1985, Thomas was among 16 Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey's Poet's Corner.[34] The inscription, written by fellow poet Wilfred Owen, reads: "My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity."[35] Thomas was described by British Poet Laureate Ted Hughes as "the father of us all."[36] Poet Laureate Andrew Motion has said that Thomas occupies "a crucial place in the development of twentieth-century poetry"[37] for introducing a modern sensibility, later found in the work of such poets as W. H. Auden and Ted Hughes, to the poetic subjects of Victorian and Georgian poetry.[38]

At least nineteen of his poems were set to music by the Gloucester composer Ivor Gurney.[39]

Legacy

[edit]Commemorations

[edit]

Thomas is commemorated in Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey, London, by memorial windows in the churches at Steep and at Eastbury in Berkshire, a blue plaque at 14 Lansdowne Gardens in Stockwell, south London, where he was born[40] and a London County Council plaque at 61 Shelgate Road SW11. The Edward Thomas Fellowship was founded in 1980 and aims to perpetuate the memory of Edward Thomas and foster interest in his life and works.

A plaque is dedicated to him at 113 Cowley Road, Oxford, where he lodged before entering Lincoln College, as well as featuring on the memorial board in the JCR of Lincoln College.[41]

East Hampshire District Council have created a "literary walk" at Shoulder of Mutton Hill in Steep dedicated to Thomas,[42] which includes a memorial stone erected in 1935. The inscription includes the final line from one of his essays: "And I rose up and knew I was tired and I continued my journey."

As "Philip Edward Thomas poet-soldier" he is commemorated, alongside "Reginald Townsend Thomas actor-soldier died 1918", who is buried at the spot, and other family members, at the North East Surrey (Old Battersea) Cemetery.

A Study Centre dedicated to Edward Thomas, featuring more than 1,800 books by or about him collected by the late Tim Wilton-Steer, has been opened in Petersfield Museum. Access to the Study Centre is available by prior appointment.[43]

Writing about Thomas

[edit]In 1918 W. H. Davies published his poem Killed in Action (Edward Thomas) to mark the personal loss of his close friend and mentor.[44] Many poems about Thomas by other poets can be found in the books Elected Friends: Poems For and About Edward Thomas, (1997, Enitharmon Press) edited by Anne Harvey, and Branch-Lines: Edward Thomas and Contemporary Poetry, (2007, Enitharmon Press) edited by Guy Cuthbertson and Lucy Newlyn. [citation needed] Eleanor Farjeon was a close friend of Thomas and after his death remained close to his wife. From her correspondence she constructed her 1958 memoir Edward Thomas: The Last Four Years.[45][46] Robert MacFarlane, in his 2012 book The Old Ways, critiques Thomas and his poetry in the context of his own explorations of paths and walking as an analogue of human consciousness.[47] The last years of Thomas's life are explored in A Conscious Englishman, a 2013 biographical novel by Margaret Keeping, published by StreetBooks.[48] Thomas is the subject of the biographical play The Dark Earth and the Light Sky by Nick Dear (2012).[49]

Sculpture

[edit]

In December 2017 National Museum Cardiff displayed a sculptural installation by the Herefordshire artist Claire Malet depicting a holloway and incorporating a copy of Thomas's Collected Poems, open at 'Roads':

- Crowding the solitude

- Of the loops over the downs,

- Hushing the roar of towns

- And their brief multitude.[50]

Selected works

[edit]Poetry collections

[edit]- Six Poems (under pseudonym Edward Eastaway) Pear Tree Press, 1916.

- Poems, Holt, 1917,[51] which included "The Sign-Post"[52]

- Last Poems, Selwyn & Blount, 1918.

- Collected Poems, Selwyn & Blount, 1920.

- Two Poems, Ingpen & Grant, 1927.

- Selected Poems of Edward Thomas. With an Introduction by Edward Garnett, Gregynog Press, 1927. 275 copies

- The Poems of Edward Thomas, ed. R. George Thomas, Oxford University Press, 1978.

- Edward Thomas: Selected Poems and Prose, ed. David Wright, Penguin Books, 1981.

- Edward Thomas: A Mirror of England, ed. Elaine Wilson, Paul & Co., 1985.

- Edward Thomas: Selected Poems, ed. Ian Hamilton, Bloomsbury, 1995.

- The Poems of Edward Thomas, ed. Peter Sacks, Handsel Books, 2003.

- The Annotated Collected Poems, ed. Edna Longley, Bloodaxe Books, 2008.

Prose

[edit]- The Woodland Life, William Blackwood and Sons, 1897

- Horae Solitariae, Duckworth, 1902

- Oxford, A & C Black, 1903

- Beautiful Wales, Black, 1905

- The Heart of England, Dent, 1906

- Richard Jefferies: His Life and Work, Hutchinson, 1909[53]

- The South Country, Dent, 1909 (republished by Tuttle, 1993), Little Toller Books (2009)[54]

- Rest and Unrest, Duckworth, 1910

- Light and Twilight, Duckworth, 1911

- Lafcadio Hearn, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912

- The Icknield Way, Constable, 1913

- Walter Pater: A Critical Study, Martin Secker, 1913

- The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans, Duckworth, 1913.[55]

- In Pursuit of Spring Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1914,[56] Little Toller Books edition 2016[57]

- Four and Twenty Blackbirds Duckworth, 1915.[58]

- A Literary Pilgrim in England, (UK: Methuen, US: Dodd, Mead and Company) 1917[59] (republished by Oxford University Press, 1980)

- The Last Sheaf, Jonathan Cape, 1928

- A Language Not to Be Betrayed, Carcanet, 1981

- Autobiographies, Oxford University Press, 2011. Volume 1 of Edward Thomas: Prose Writings: A Selected Edition.

References

[edit]- ^ see James, B. Ll. (1993) pp84-85

- ^ Longley, Edna. "Thomas, (Philip) Edward". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36480. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ James, B. Ll. (1993). "The Ancestry of Edward Thomas". National Library of Wales Journal. 28, 1: 81–93.

- ^ The birth places of the five great-grandparents born in Wales were Cadoxton (2), Caerleon, Port Talbot and Pyle. By the time of her marriage in 1825, the Ilfracombe great-grandparent and her parents were already living in Swansea. For more, see See James, B. Ll. (1993).

- ^ Edward Thomas's paternal grandfather, Henry Eastaway Thomas, had been born in Neath, worked in Cwmafan and moved to Tredegar in the 1850s. He was the brother of Treharne Thomas of Pontarddulais, with whose family Edward Thomas would later stay. Philip Henry Thomas left Tredegar in his early teens, when his parents moved to Swindon and then London. See James, B. Ll. (1993) pp81-83, 93.

- ^ For more on the Townsend and Marendaz families, see B. LL. James (1993) pp85-89, with a family tree on page 93, and A. L. Evans (1967).

- ^ See James, B. Ll. (1993) pp84

- ^ See James, B. Ll. (1993) pp84-85, 90

- ^ His account of journeys to Wales as a child mentions calling on relatives in Newport, Caerleon, Swansea, Abertillery and Pontypool. See pp20,22 and 54 of Thomas, E. (1983)

- ^ Thomas's relatives in Pontardulais were the family of his great-uncle, Treharne Thomas, who lived in 17, Woodville Street. For more on Edward Thomas and Pontardulais, see R. G. Thomas (1987).

- ^ For more on Gwili and Thomas, see Jenkins, E. (1967) pp148-154

- ^ "Elegy". John Jenkins (Gwili).

- ^ See Jenkins, E. (1967) p148

- ^ "Famous Lincoln Alumni". Lincoln.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ "Edward Thomas". library.wales. The National Library of Wales. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ a b Abrams, MH (1986). The Norton Anthology of English Literature. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 1893. ISBN 0-393-95472-2.

- ^ Andreas Dorschel, 'Die Freuden der Unordnung', Süddeutsche Zeitung nr 109 (13 May 2005), p. 16.

- ^ a b Stonesifer, R. J. (1963), W. H. Davies – A Critical Biography, London, Jonathan Cape. B0000CLPA3.

- ^ "THOMAS, PHILIP EDWARD (1878 - 1917), poet | Dictionary of Welsh Biography".

- ^ Hollis, Matthew (29 July 2011). "Edward Thomas, Robert Frost and the road to war". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 September 2013.

- ^ "Dymock Poets Archive", Archives, UK: University of Gloucestershire, archived from the original on 21 May 2009

- ^ "Adlestrop". www.poetsgraves.co.uk. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ a b Hollis, Matthew (29 July 2011). "Edward Thomas, Robert Frost and the road to war". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Wilson 2015, p. 343.

- ^ Farjeon 1997, pp. 237–238.

- ^ "France: First World War Poetry". The Daily Telegraph. London. 27 February 1999. Archived from the original on 5 August 2008.

- ^ "Edward Thomas - poetryarchive.org". www.poetryarchive.org. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ "Casualty Details: Thomas, Philip Edward". Debt of Honour Register. Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ^ "Helen Thomas". spartacus-educational.com. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Edna Longley, England and Other Women, London Review of Books, Edna Longley, 5 May 1988.

- ^ Motion, Andrew. 'Lost father', in The Times Literary Supplement Issue 4137, 16 July 1982, p. 760

- ^ "In Memoriam (Easter 1915) - First World War Poetry Digital Archive". Oucs.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 19 May 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ "Poets", The Great War, Utah, USA: Brigham Young University, archived from the original on 22 September 2008, retrieved 19 September 2008

- ^ "Preface", The Great War, Utah, USA: Brigham Young University

- ^ "The timeless landscape of Edward Thomas", The Daily Telegraph, UK, 8 April 2007

- ^ Motion, Andrew (2011). The Poetry Of Edward Thomas. United Kingdom: Random House. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4464-9818-7. OCLC 1004975686.

- ^ "Edward Thomas". 26 December 2021.

- ^ "Composer: Ivor (Bertie) Gurney (1890–1937)". recmusic.org. Retrieved 24 July 2013. [permanent dead link]

- ^ The Vauxhall Society@vauxhallsociety (9 April 1917). "Edward Thomas". Vauxhallcivicsociety.org.uk. Retrieved 1 January 2016. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Cowley Road". Oxfordhistory.org.uk. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Walking in East Hampshire, East Hampshire, UK: District Council, archived from the original on 5 October 2010

- ^ "Edward Thomas | Petersfield Museum". www.petersfieldmuseum.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Davies, W.H. (1918), Forty New Poems, A.C. Fifield. ASIN: B000R2BQIG

- ^ Farjeon 1997.

- ^ "Eleanor Farjeon - Authors - Faber & Faber". Faber.co.uk. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Robert MacFarlane, 2012, The Old Ways, Robert MacFarlane, Hamish Hamilton, 2012, pp 333-355

- ^ Roberts, Gabriel (10 June 2010). "The Creations of Edward Thomas". Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ "Almeida". Almeida. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "PoemHunter.com". 16 June 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ Henderson, Alice Corbin (13 October 2017). Thomas, Edward (ed.). "The Late Edward Thomas". Poetry. 12 (2): 102–105. JSTOR 20571689.

- ^ "The Sign-Post by Edward Thomas". Poetry Foundation. 12 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Catalog Record: Richard Jefferies : His life and work | HathiTrust Digital Library. Hutchinson. 1908.

- ^ "The South Country by Edward Thomas, Little Toller Books". 16 May 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ "The happy-go-lucky Morgans : Thomas, Edward, 1878–1917 : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "In pursuit of spring : Thomas, Edward, 1878–1917 : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "In Pursuit of Spring by Edward Thomas, Little Toller Books". Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ Thomas, Edward (9 September 2016). Four-And-Twenty Blackbirds. Read Books. ISBN 9781473359734.

- ^ Edward Thomas (23 June 2018). "A Literary Pilgrim in England". Dodd, Mead. Retrieved 23 June 2018 – via Internet Archive.

Additional sources

[edit]- Hollis, Matthew (2011). Now All Roads Lead to France: The Last Years of Edward Thomas. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-24598-7.

Bibliography

[edit]- Farjeon, Eleanor (1997) [1958 OUP]. Edward Thomas: The Last Four Years (Revised ed.). Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-1337-9. (Full text on Internet Archive) (memoir constructed from her correspondence with Thomas)

- James, B. Ll. (1993). "The Ancestry of Edward Thomas". National Library of Wales Journal. 28, 1: 81–93.

- Jenkins, E. (1967). "50th Anniversary of the Death of Edward Thomas (1878-1917) Some of His Welsh Friends". National Library of Wales Journal. 15, 2: 147–156.

- Thomas, E. (1983). The Childhood of Edward Thomas: A Fragment of Autobiography. London: Faber & Faber.

- Thomas, P. H. (1913). A Religion of this World: Being a Selection of Positivist Addresses. London: Watts.

- Thomas, R.G. (1987). Edward Thomas: A Portrait. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-818527-7.

- Towns, Jeff, ed. (2018). Edward Thomas & Wales. Cardigan: Parthian. ISBN 9781912681129.

- Wilson, Jean Moorcroft (2015). Edward Thomas: from Adlestrop to Arras; a biography. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4081-8713-5.

External links

[edit]- https://edward-thomas-fellowship.org.uk/

- https://edward-thomas-fellowship.org.uk/the-edward-thomas-study-centre/

- Edward Thomas profile, Poets.org.

- Edward Thomas profile, Poetry Foundation, 26 December 2021.

- Works by Edward Thomas at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Edward Thomas at the Internet Archive

- Works by Edward Thomas at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Thomas, Edward, Works, Internet Archive.

- Edward Thomas Fellowship, UK: The Edward Thomas Fellowship.

- "Dymock Poets Archive", Archives and Special Collections, UK: University of Gloucestershire, archived from the original on 21 May 2009.

- Edward Thomas Archive at Cardiff University

- "The Edward Thomas Collection", The First World War Poetry Digital Archive, UK: Oxford University, archived from the original on 2 December 2008, retrieved 13 November 2008

- "Archival material relating to Edward Thomas". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of Edward Thomas at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Edward Thomas Study Centre at Petersfield Museum

- Edward and Helen Thomas manuscripts at the National Library of Wales

- The digitised war diary of Edward Thomas at the National Library of Wales

KSF

KSF