Electricity sector in China

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

| |

| Data | |

|---|---|

| Installed capacity (2023) | 2919 GW |

| Production (2021) | 8.5 petawatt-hour (PWh) |

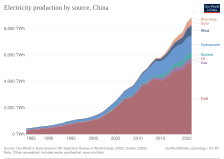

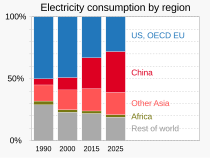

China is the world's largest electricity producer, having overtaken the United States in 2011 after rapid growth since the early 1990s. In 2021, China produced 8.5 petawatt-hour (PWh) of electricity, approximately 30% of the world's electricity production.[2]

Most of the electricity in China comes from coal power, which accounted for 62% of electricity generation in 2021[2] and is a big part of greenhouse gas emissions by China. Power generated from renewable energy has also been continuously increasing in the country, with national electricity generation from renewable energy reaching 594.7 TWh in Q1 2023, an increase of 11.4% year-on-year, including 342.2 TWh of wind and solar power, up 27.8% year-on-year.[3]

In 2023, China's total installed electric generation capacity was 2.92 TW,[4] of which 1.26 TW renewable, including 376 GW from wind power and 425 GW from solar power.[3] As of 2023, the total power generation capacity for renewable energy sources in China is at 53.9%.[5] The rest was mostly coal capacity, with 1040 GW in 2019.[6] Nuclear also plays an increasing role in the national electricity sector. As of February 2023, China has 55 nuclear plants with 57 GW of power in operation, 22 under construction with 24 GW and more than 70 planned with 88 GW. About 5% of electricity in the country comes from nuclear energy.[7]

China has two wide area synchronous grids, the State Grid and the China Southern Power Grid. The northern power grids were synchronized in 2005.[8] Since 2011 all Chinese provinces are interconnected. The two grids are joined by HVDC back-to-back connections.[9]

China has abundant energy reserves with the world's fourth-largest coal reserves and massive hydroelectric resources. There is however a geographical mismatch between the location of the coal fields in the north-east (Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning) and north (Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Henan), hydropower in the south-west (Sichuan, Yunnan, and Tibet), and the fast-growing industrial load centers of the east (Shanghai-Zhejiang) and south (Guangdong, Fujian).[10][better source needed]

History

[edit]In April 1996, an Electric Power Law was implemented, a major event in China's electric power industry. The law set out to promote the development of the electric power industry, to protect the legal rights of investors, managers, and consumers, and to regulate the generation, distribution, and consumption.[citation needed]

Before 1994, electricity supply was managed by electric power bureaus of the provincial governments. Now utilities are managed by corporations outside of the government administration structure.[citation needed]

To end the State Power Corporation's (SPC) monopoly of the power industry, China's State Council dismantled the corporation in December 2002 and set up 11 smaller companies. SPC had owned 46% of the country's electrical generation assets and 90% of the electrical supply assets. The smaller companies include two electric power grid operators, five electric power generation companies, and four relevant business companies. Each of the five electric power generation companies owns less than 20% (32 GW of electricity generation capacity) of China's market share for electric power generation. Ongoing reforms aim to separate power plants from power-supply networks, privatize a significant amount of state-owned property, encourage competition, and revamp pricing mechanisms.[11]

In recent history, China's power industry is characterized by fast growth and an enormous installed base. In 2014, it had the largest installed electricity generation capacity in the world with 1505 GW and generated 5583 TWh[12] China also has the largest thermal power capacity, the largest hydropower capacity, the largest wind power capacity and the largest solar capacity in the world. Despite an expected rapid increase in installed capacity scheduled in 2014 for both wind and solar, and an expected increase to 60 GW in nuclear by 2020, coal will still account for between 65% and 75% of capacity in 2020.[13]

In Spring 2011, according to The New York Times, shortages of electricity existed, and power outages should be anticipated. The government-regulated price of electricity had not matched rising prices for coal.[14]

In 2020, Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping announced that China aims to go carbon-neutral by 2060 in accordance with the Paris climate accord.[15]

In 2024, China's National Energy Administration ceased publishing data on power utilization by each generating source, impeding analysis of grid constraints.[16]

Production and capacity

[edit]- Wind

- Solar

- Hydro

- Biofuels and waste

- Nuclear

- Coal

- Oil

- Gas

- Fossil (Inc. Biomass)

| Year | Total | Fossil | Nuclear | Renewable | Total renewable |

% renewable | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coal | Oil | Gas | Hydro | Wind | Solar PV | Biofuels | Waste | Solar thermal | Geo- thermal |

Tide | |||||

| 2008 | 3,481,985 | 2,743,767 | 23,791 | 31,028 | 68,394 | 585,187 | 14,800 | 152 | 14,715 | 0 | 0 | 144 | 7 | 615,005 | 17.66% |

| 2009 | 3,741,961 | 2,940,751 | 16,612 | 50,813 | 70,134 | 615,640 | 26,900 | 279 | 20,700 | 0 | 0 | 125 | 7 | 663,651 | 17.74% |

| 2010 | 4,207,993 | 3,250,409 | 13,236 | 69,027 | 73,880 | 722,172 | 44,622 | 699 | 24,750 | 9,064 | 2 | 125 | 7 | 801,441 | 19.05% |

| 2011 | 4,715,761 | 3,723,315 | 7,786 | 84,022 | 86,350 | 698,945 | 70,331 | 2,604 | 31,500 | 10,770 | 6 | 125 | 7 | 814,288 | 17.27% |

| 2012 | 4,994,038 | 3,785,022 | 6,698 | 85,686 | 97,394 | 872,107 | 95,978 | 6,344 | 33,700 | 10,968 | 9 | 125 | 7 | 1,019,238 | 20.41% |

| 2013 | 5,447,231 | 4,110,826 | 6,504 | 90,602 | 111,613 | 920,291 | 141,197 | 15,451 | 38,300 | 12,304 | 26 | 109 | 8 | 1,127,686 | 20.70% |

| 2014 | 5,678,945 | 4,115,215 | 9,517 | 114,505 | 132,538 | 1,064,337 | 156,078 | 29,195 | 44,437 | 12,956 | 34 | 125 | 8 | 1,307,170 | 23.02% |

| 2015 | 5,859,958 | 4,108,994 | 9,679 | 145,346 | 170,789 | 1,130,270 | 185,766 | 45,225 | 52,700 | 11,029 | 27 | 125 | 8 | 1,425,180 | 24.32% |

| 2016 | 6,217,907 | 4,241,786 | 10,367 | 170,488 | 213,287 | 1,193,374 | 237,071 | 75,256 | 64,700 | 11,413 | 29 | 125 | 11 | 1,581,979 | 25.44% |

| 2017 | 6,452,900 | 4,178,200 | 2,700 | 203,200 | 248,100 | 1,194,700 | 304,600 | 117,800 | 81,300 | 1,700,000 | 26.34% | ||||

| 2018 | 6,994,700 | 4,482,900 | 1,500 | 215,500 | 295,000 | 1,232,100 | 365,800 | 176,900 | 93,600 | 1,868,400 | 26.71% | ||||

| 2019 | 7,326,900 | 4,553,800 | 1,300 | 232,500 | 348,700 | 1,302,100 | 405,300 | 224,000 | 112,600 | 2,044,000 | 27.76% | ||||

| 2020 | 7,623,600 | 4,629,600 | 10,800 | 252,500 | 366,200 | 1,355,200 | 466,500 | 261,100 | 43,800 | 135,500 | 2,218,300 | 29.09% | |||

| 2021 | 8,395,900 | 5,042,600 | 12,200 | 287,100 | 407,500 | 1,339,900 | 655,800 | 327,000 | 50,200 | 165,800 | 2,488,500 | 29.64% | |||

| 2022 | 8,848,710 | 5,888,790 | 417,780 | 1,352,200 | 762,670 | 427,270 | 2,542,120 | 28.73% | |||||||

| 2023 | 9,456,440 | 6,265,740 | 434,720 | 1,285,850 | 885,870 | 584,150 | 2,755,880 | 29.14% | |||||||

| Total | From coal | Coal % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2,200 | 1,713 | 78% |

| 2007 | 3,279 | 2,656 | 81% |

| 2008 | 3,457 | 2,733 | 79% |

| 2009 | 3,696 | 2,913 | 79% |

| 2010 | 4,208 | 3,273 | 78% |

| 2011 | 4,715 | 3,724 | 79% |

| 2012 | 4,937 | 3,850 | 78% |

| 2013 | 5,398 | 4,200 | 78% |

| 2014 | 5,583 | 4,354 | 78% |

| 2015 | 5,666 | 4,115 | 73% |

| 2016 | 5,920 | 3,906 | 66%[24] |

| 2017 | 6,453 | 4,178 | 65% |

| 2018 | 6,995 | 4,483 | 64% |

| 2019 | 7,327 | 4,554 | 62% |

| 2020 | 7,623 | 4,926 | 60.7% |

| 2021 | 8,395 | 5,042 | 60% |

| excluding Hong Kong | |||

- ChinaEnergyPortal.org

China Energy Portal publishes Chinese energy policy, news, and statistics and provides tools for their translation into English. Translations on this site depend entirely on contributions from its readers. 2020 electricity & other energy statistics (preliminary)[25]

| Source | 2019 [TWh] | 2020 [TWh] | Change [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total power production | 7,326.9 | 7,623.6 | 4.0 |

| Hydro power | 1,302.1 | 1,355.2 | 4.1 |

| Thermal power | 5,046.5 | 5,174.3 | 2.5 |

| Nuclear power | 348.7 | 366.2 | 5.0 |

| Wind power | 405.3 | 466.5 | 15.1 |

| Solar power | 224 | 261.1 | 16.6 |

| Source | 2019 [GW] | 2020 [GW] | Change [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Installed generation capacity | 2,010.06 | 2,200.58 | 9.5 |

| Hydro power | 358.04 | 370.16 | 3.4 |

| Thermal power | 1,189.57 | 1,245.17 | 4.7 |

| Nuclear power | 48.74 | 49.89 | 2.4 |

| Wind power | 209.15 | 281.53 | 34.6 |

| Solar power | 204.18 | 253.43 | 24.1 |

| Source | 2019 [MW] | 2020 [MW] | Change [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change in generation capacity | 105,000 | 190,870 | 81.8 |

| Hydro power | 4,450 | 13,230 | 197.7 |

| Thermal power | 44,230 | 56,370 | 27.4 |

| Nuclear power | 4,090 | 1,120 | −72.6 |

| Wind power | 25,720 | 71,670 | 178.7 |

| Solar power | 26,520 | 48,200 | 81.7 |

(Note that change in generation capacity is new installations minus retirements.)

- National Bureau of Statistics of China

The official Statistics available in English are not all up to date. Numbers are given in "(100 million kw.h)"[26] which equals 100 GWh or 0.1 TWh.

| Electricity Production by source | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydro Power | 6989.4 | 8721.1 | 9202.9 | 10728.8 | 11302.7 | 11840.5 | 11978.7 | 12317.9 | 13044.4 | 13552.1 | 13401 |

| Thermal Power | 38337 | 38928.1 | 42470.1 | 44001.1 | 42841.9 | 44370.7 | 47546 | 50963.2 | 52201.5 | 53302.5 | 56463 |

| Nuclear Power | 863.5 | 973.9 | 1116.1 | 1325.4 | 1707.9 | 2132.9 | 2480.7 | 2943.6 | 3481 | 3662 | 4075 |

| Wind Power | 703.3 | 959.8 | 1412 | 1599.8 | 1857.7 | 2370.7 | 2972.3 | 3659.7 | 4057 | 4665 | 6556 |

| Solar Power | 26 | 63.4 | 154.5 | 292 | 452.3 | 752.6 | 1178 | 1769 | 2240 | 2611 | 3270 |

Sources

[edit]Coal power

[edit]

Coal power in China is electricity generated from coal in China and is distributed by the State Power Grid Corporation. It is a big source of greenhouse gas emissions by China.

China's installed coal-based power generation capacity was 1080 GW in 2021,[27] about half the total installed capacity of power stations in China.[28] Coal-fired power stations generated 57% of electricity in 2020.[29] Over half the world's coal-fired power is generated in China.[30] 5 GW of new coal power was approved in the first half of 2021.[28] Quotas force utility companies to buy coal power over cheaper renewable power.[31] China is the largest producer and consumer of coal in the world and is the largest user of coal-derived electricity. Despite China (like other G20 countries) pledging in 2009 to end inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, as of 2020[update] there are direct subsidies and the main way coal power is favoured is by the rules guaranteeing its purchase – so dispatch order is not merit order.[32]

The think tank Carbon Tracker estimated in 2020 that the average coal fleet loss was about 4 USD/MWh and that about 60% of power stations were cashflow negative in 2018 and 2019.[33] In 2020 Carbon Tracker estimated that 43% of coal-fired plants were already more expensive than new renewables and that 94% would be by 2025.[34] According to 2020 analysis by Energy Foundation China, to keep warming to 1.5 degrees C all China's coal power without carbon capture must be phased out by 2045.[35] But in 2023 many new coal power stations were approved.[36] Coal power stations receive payments for their capacity.[37] A 2021 study estimated that all coal power plants could be shut down by 2040, by retiring them at the end of their financial lifetime.[38]

To curtail the continued rapid construction of coal fired power plants, strong action was taken in April 2016 by the National Energy Administration (NEA), which issued a directive curbing construction in many parts of the country.[42] This was followed up in January 2017 when the NEA canceled a further 103 coal power plants, eliminating 120 GW of future coal-fired capacity, despite the resistance of local authorities mindful of the need to create jobs.[43] The decreasing rate of construction is due to the realization that too many power plants had been built and some existing plants were being used far below capacity.[44] In 2020 over 40% of plants were estimated to be running at a net loss and new plants may become stranded assets.[32] In 2021 some plants were reported close to bankruptcy due to being forbidden to raise electricity prices in line with high coal prices.[45]

As part of China's efforts to achieve its pledges of peak coal consumption by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060, a nationwide effort to reduce overcapacity resulted in the closure of many small and dirty coal mines.[46]: 70 Major coal-producing provinces like Shaanxi, Inner Mongolia, and Shanxi instituted administrative caps on coal output.[46]: 70 These measures contributed to electricity outages in several northeastern provinces in September 2021 and a coal shortage elsewhere in China.[46]: 70 The National Development and Reform Commission responded by relaxing some environmental standards and the government allowed coal-fired power plants to defer tax payments.[46]: 71 Trade policy was adjusted to permit the importation of a small amount of coal from Australia.[46]: 72 The energy problems abated in a few weeks.[46]: 72

In 2023, The Economist wrote that ‘Building a coal plant, whether it is needed or not, is also a common way for local governments to boost economic growth.’ and that ‘They don’t like depending on each other for energy. So, for example, a province might prefer to use its own coal plant rather than a cleaner energy source located elsewhere.’[47]Hydropower

[edit]

Hydroelectricity is currently China's largest renewable energy source and the second overall after coal.[48] China's installed hydro capacity in 2020 was 370 GW,[49] this is an increase of 51 GW over the 2015 number of 319 GW, and up from 172 GW in 2009, including pumped storage hydroelectricity capacity. In 2021, hydropower generated 1,300 TWh of power, accounting for 15% of China's total electricity generation.[2] In contrast, in 2015 hydropower generated 1,126 TWh of power, accounting for roughly 20% of China's total electricity generation.[50]

Due to China's insufficient reserves of fossil fuels and the government's preference for energy independence, hydropower plays a big part in the energy policy of the country. China's potential hydropower capacity is estimated at up to 600 GW, but currently, the technically exploitable and economically feasible capacity is around 500 GW.[citation needed] There is therefore the considerable potential for further hydro development.[48] The country has set a 350 GW capacity target for 2020.[48] Being flexible, existing hydropower can back up large amounts of solar and wind.[51]

Hydroelectric plants in China have relatively low productivity, with an average capacity factor of 31%, a possible consequence of rushed construction[48] and the seasonal variability of rainfall. Moreover, a significant amount of energy is lost due to the need for long transmission lines to connect the remote plants to where demand is most concentrated.[48]

Although hydroelectricity represents the largest renewable and low greenhouse gas emissions energy source in the country, the social and environmental impact of dam construction in China has been large, with millions of people forced to relocate and large scale damage to the environment.[52]

Wind power

[edit]

With its large land mass and long coastline, China has exceptional wind resources:[53] it is estimated China has about 2,380 GW of exploitable capacity on land and 200 GW on the sea.[54] At the end of 2021 there was 329 GW of Wind power in China proving 655,000 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of wind electricity to the grid[2] This contrast with the 114 GW of electricity generating capacity installed in China in 2014[55] (although capacity of wind power is not on par with capacity of nuclear power).[56] In 2011, China's plan was to have 100 GW of wind power capacity by the end of 2015, with an annual wind generation of 190 terawatt-hours (TWh).[57]

China has identified wind power as a key growth component of the country's economy.[58]

Nuclear power

[edit]In terms of nuclear power generation, China will advance from a moderate development strategy to an accelerating development strategy. Nuclear power will play an even more important role in China's future power development. Especially in the developed coastal areas with heavy power loads, nuclear power will become the backbone of the power structure there. As of February 2023, China has 55 plants with 57 GW of power in operation, 22 under construction with 24 GW and more than 70 planned with 88 GW. About 5% of electricity in the country is due to nuclear energy.[7] These plants generated 417 TWh of electricity in 2022. [59] This percentage is expected to double every 10 years for several decades out. Plans are for 200 GW installed by 2030 which will include a large shift to Fast Breeder reactor and 1500 GW by the end of this century.

Solar power

[edit]China is the world's largest market for both photovoltaics and solar thermal energy. At the end of 2021 there was 306 GW of solar power in China proving 377,000 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of solar power electricity to the grid (out of total 7,770,000 GWh electricity power production.[2] In comparison, of the 7,623 TWh electricity produced in China in 2020, 261.1 TWh was generated by solar power, equivalent to 3.43% of total electricity production.[60] This was a 289% increase since 2016, when production was 67.4 TWh,[61] equivalent to an annual growth rate of 40.4%.

China has been the world's leading installer of solar photovoltaics since 2013 (see also growth of photovoltaics), and the world's largest producer of photovoltaic power since 2015.[62][63][64] In 2017 China was the first country to pass 100 GW of cumulative installed PV capacity.[65] However electricity prices are not properly varied by time of day, so do not properly incentivize system balancing.[66]

Solar water heating is also extensively implemented, with a total installed capacity of 290 GWth at the end of 2014, representing about 70% of world's total installed solar thermal capacity.[67][68] The goal for 2050 is to reach 1,300GW of Solar Capacity. If this goal is to be reached it would be the biggest contributor to Chinese electricity demand.[69]

Natural gas

[edit]China produced 272 Twh of electricity from natural gas in 2021.[2]

China is a global powerhouse in the field of natural gas and one of the world's largest consumers and importers of natural gas. By the end of 2023, China's natural gas industry achieved major milestones, reflecting its important role in the country's energy transformation and its contribution to global natural gas market dynamics.

In 2023, China's natural gas production will increase significantly, with the total volume reaching approximately 229.7 billion cubic meters.[70] This represents an increase of nearly 10 billion cubic meters per year and highlights China's efforts to increase domestic production and reduce reliance on imports. Despite the increase in domestic production, China remains the world's largest importer of liquefied natural gas (LNG), importing approximately 165.56 billion cubic meters of natural gas, of which LNG imports account for a large portion.[70] This import capacity strengthens China's key role in the international LNG market and reflects its strategic measures to ensure energy security and supply stability.

Natural gas demand also rebounded, with apparent consumption increasing to 388.82 billion cubic meters. The growth highlights the growing role of natural gas in China's energy mix, driven by its economic recovery and transition to clean energy. Natural gas import dependence is 40.9%, indicating a balance between domestic production and imports to meet the country's energy needs.[70]

Biomass and waste

[edit]

China produced 169 Twh of electricity from biomass, geothermal and other renewable sources of energy in 2021.[2]

Since the implementation of supportive policies beginning in 2006, investment and growth in the biomass power sector have accelerated. By 2019, investments had reached an impressive 150.2 billion yuan, climbing further to over 160 billion yuan by 2020, with more than 1,350 biomass projects underway across the country. This growth trajectory has been marked by a significant increase in installed capacity, which saw a record addition of 6,280 MW in 2019. Although the COVID-19 pandemic slightly slowed momentum in 2020, reducing the added capacity to 5,430 MW, the sector's growth trend continued upwards.[71]

Policy initiatives introduced in 2012 and 2016 have been pivotal in spurring the expansion of biomass power generation, leading to a substantial increase in power output. By 2019, biomass power generation had achieved a total output of 111,100 GWh, which further rose to 132,600 GWh in 2020, indicating robust year-on-year growth.[71]

Storage

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2021) |

Energy storage plays a critical role in China's energy landscape, serving as a key enabler for the large-scale integration of renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar power, into the national grid. By mitigating the variability and intermittency of renewable energy, storage technologies facilitate a more stable and reliable power supply. China has been investing heavily in various storage solutions, including battery storage systems, pumped hydro storage, and flywheel energy storage, among others. These technologies not only help in balancing supply and demand but also in improving the overall efficiency and resilience of the power system.

In 2023, China's energy storage industry saw a dramatic surge, with its capacity expanding nearly fourfold due to advancements in technologies such as lithium-ion batteries. This remarkable growth was fueled by an investment exceeding 100 billion yuan (around US$13.9 billion) in recent years. By the close of 2023, the capacity within the sector of new-type energy storage soared to 31.39 gigawatts (GW), achieving an increase of over 260% compared to the previous year and almost a tenfold rise since 2020. The sector encompasses a range of innovative technologies, including electrochemical energy storage, compressed air energy storage, flywheel energy storage, and thermal energy storage, while pumped hydro storage is not included in this category.[72]

Demand response

[edit]China's government has introduced a number of policies to promote the development of demand response, such as the 2012 "Interim Measures for the Management of Pilot Cities with Central Fiscal Funds to Support Electricity Demand Side Management."[73] The DR mechanism incentivizes electricity users to adjust their consumption patterns based on signals from grid operators, either reducing demand during peak hours (peak shaving) or increasing demand during off-peak hours (valley filling). This flexibility is critical to maintaining grid stability and ensuring efficient use of energy resources.[74]

China's approach to DR has included pilot projects in cities like Suzhou, Beijing, and Shanghai, focusing on tariff reforms and pricing strategies to encourage participation. Despite these efforts, challenges remain, such as the low participation rate of grid companies and the lack of transparency in grid operation data, hindering the widespread adoption of DR.[73]

The types of demand response in China are:[74]

- Invitation DR: Local governments or grid companies invite consumers to participate in DR events, offering financial incentives for adjusting their load during specified times.[74][75]

- Real-time DR: Requires participants to respond to demand response signals in real-time, often with minimal notice, to address immediate grid needs.

- Economic DR: Utilizes price signals, such as peak and off-peak rates, to motivate consumers to voluntarily adjust their energy usage according to the cost of electricity.

Transmission infrastructure

[edit]

The central government has made the creation of a unified national grid system a top economic priority to improve the efficiency of the whole power system and reduce the risk of localised energy shortages. It will also enable the country to tap the enormous hydro potential from western China to meet booming demand from the eastern coastal provinces. China is planning for smart grid and related Advanced Metering Infrastructure.[76]

Ultra-high-voltage transmission

[edit]The main problem in China is the voltage drop when power is sent over very long distances from one region of the country to another.

Long distance inter-regional transmission has been implemented by using ultra-high voltages (UHV) of 800 kV, based on an extension of technology already in use in other parts of the world.[77]

In 2015, State Grid Corporation of China proposed the Global Energy Interconnection, a long-term proposal to develop globally integrated smart grids and ultra high voltage transmission networks to connect over 80 countries.[78]: 92–93 The idea is supported by President Xi Jinping and China in attempting to develop support in various internal forums, including UN bodies.[78]: 92

Companies

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

In terms of the investment amount of China's listed power companies, the top three regions are Guangdong province, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and Shanghai, whose investment ratios are 15.33%, 13.84% and 10.53% respectively, followed by Sichuan and Beijing.

China's listed power companies invest mostly in thermal power, hydropower and thermoelectricity, with their investments reaching CNY216.38 billion, CNY97.73 billion, and CNY48.58 billion respectively in 2007. Investment in gas exploration and coal mining follow as the next prevalent investment occurrences.

Major players in China's electric power industry include:

The five majors, and their listed subsidiaries: The five majors are all SOEs directly administered by SASAC.[79] Their listed subsidiaries are substantially independent, hence counted as IPPs, and are major power providers in their own right. Typically each of the big 5 has about 10% of national installed capacity, and their listed subsidiary has an extra 4 or 5% on top of that.

- parent of Datang International Power Generation Company (SEHK: 991; SSE: 601991)

- China Guodian Corporation ("Guodian")

- parent of GD Power Development Company (SSE: 600795),

- parent of Huadian Power International Co., Ltd.

- parent of Huaneng Power International (NYSE:HNP)

- State Power Investment Corporation ("SPIC")

- parent of China Power International Development Limited ("CPID", 2380.HK)

Additionally, two other SOEs also have listed IPP subsidiaries:

- the coalmine owning Shenhua Group

- parent of China Shenhua Energy Company (SEHK: 1088, SSE: 601088)

- China Resources Group ("Huarun")

- parent of China Resources Power Holdings Company Limited ("CRP", SEHK: 836)

Secondary companies:

- Shenzhen Energy Co., Ltd.

- Guangdong Yuedian Group Co., Ltd.

- Anhui Province Energy Group Co., Ltd.

- Hebei Jiantou Energy Investment Co., Ltd.

- Guangdong Baolihua New Energy Stock Co., Ltd.

- Shandong Luneng Taishan Cable Co., Ltd.

- Guangzhou Development Industry (Holdings) Co., Ltd.

- Chongqing Jiulong Electric Power Co., Ltd.

- Chongqing Fuling Electric Power Industrial Co., Ltd.

- Shenergy Company (SSE: 600642), Shanghai.

- Shenergy Group, Shanghai.

- Sichuan Chuantou Energy Stock Co., Ltd.

- Naitou Securities Co., Ltd.

- Panjiang Coal and Electric Power Group

- Hunan Huayin Electric Power Co., Ltd.

- Shanxi Top Energy Co., Ltd.

- Inner Mongolia Mengdian Huaneng Thermal Power Co., Ltd.

- SDIC Huajing Power Holdings Co., Ltd.[80][81]

- Sichuan MinJiang Hydropower Co., Ltd.

- Yunnan Wenshan Electric Power Co., Ltd.

- Guangxi Guidong Electric Power Co., Ltd.

- Sichuan Xichang Electric Power Co., Ltd.

- Sichuan Mingxing Electric Power Co., Ltd.

- Sichuan Guangan Aaa Public Co., Ltd.

- Sichuan Leshan Electric Power Co., Ltd.

- Fujian MingDong Electric Power Co., Ltd.

- Guizhou Qianyuan Power Co., Ltd.

Nuclear and hydro:

- China Three Gorges Corporation

- China Guangdong Nuclear Power Group

- China Yangtze Power (listed)

- Sinohydro Corporation an engineering company.

- Guangdong Meiyan Hydropower Co., Ltd.

Grid operators include:

- State Grid Corporation of China

- China Southern Power Grid

- Wenzhou CHINT Group Corporation ("Zhengtai")

Creation of a spot market has been suggested to properly use energy storage.[82]

Consumption and territorial differences

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

More than a third of electricity is used by industry.[83] China consists of three largely self-governing territories: the mainland, Hong Kong, and Macau. The introduction of electricity to the country was not coordinated between the territories, leading to partially different electrical standards. Mainland China uses type A and I power plugs with 220 V and 50 Hz; Hong Kong and Macau both use type G power plugs with 220 V and 50 Hz. Inter-territorial travelers may therefore require a power adapter.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Electricity Market Report 2023" (PDF). IEA.org. International Energy Agency. February 2023. p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 March 2023. Licensed CC BY 4.0.

- ^ a b c d e f g https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2022-full-report.pdf

- ^ a b "China's first desert-based green power plant on grid - Chinadaily.com.cn" (in Chinese). Global.chinadaily.com.cn. 28 April 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ "China's installed solar power capacity rises 55.2% in 2023". Reuters.

- ^ Yin, Ivy (24 January 2024). "Coal still accounted for nearly 60% of China's electricity supply in 2023: CEC".

- ^ "Corrected-China to cap 2020 coal-fired power capacity at 1,100 GW". Reuters. 18 June 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.[dead link]

- ^ a b "How Long Will It Take For China's Nuclear Power To Replace Coal?". Forbes.com. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ Wu, Wei; He, Zhao; Guo, Qiang (June 2005). "China power grid and its future development". IEEE Power Engineering Society General Meeting, 2005. pp. 1533–1535. doi:10.1109/pes.2005.1489157. ISBN 0-7803-9157-8. S2CID 30004029.

- ^ Zhenya, Liu (28 August 2015). Global energy interconnection. Academic Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780128044063.

After the completion and commissioning of Tibet's ±400 kV DC interconnected power grid in December 2011, China has achieved nationwide interconnections covering all its territories other than Taiwan.

- ^ Kambara, Tatsu (1992). "The Energy Situation in China". The China Quarterly. 131 (131): 608–636. doi:10.1017/S0305741000046312. ISSN 0305-7410. JSTOR 654899. S2CID 154871503.

- ^ "BuyUSA.gov Home". Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ "The World Factbook". cia.gov. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ "China and Electricity Overview – The Energy Collective". Theenergycollective.com. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith (24 May 2011). "China's Utilities Cut Energy Production, Defying Beijing". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

Balking at the high price of coal that fuels much of China's electricity grid, the nation's state-owned utility companies are defying government economic planners by deliberately reducing the amount of electricity they produce.

- ^ "China Solar Stocks Are Surging After Xi's 2060 Carbon Pledge". Bloomberg News. 8 October 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ "China Stops Publishing Data Highlighting Solar Power Constraints". Bloomberg News. 1 July 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ "IEA – Report". www.iea.org. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ "2020 electricity & other energy statistics (preliminary)". China Energy Portal | 中国能源门户. 22 January 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "2019 detailed electricity statistics (update of Jan 2021)". China Energy Portal | 中国能源门户. 20 January 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "中国电力企业联合会网-中国最大的行业门户网站". www.cec.org.cn. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "中华人民共和国2022年国民经济和社会发展统计公报 - 国家统计局". www.stats.gov.cn. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "中华人民共和国2023年国民经济和社会发展统计公报 - 国家统计局". www.stats.gov.cn. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ IEA Key World Energy Statistics 2015, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009 Archived 7 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 2006 Archived 12 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine IEA coal production p. 15, electricity p. 25 and 27

- ^ "China's renewable energy revolution continues on its long march". Energypost.eu. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ Published on: 22 January 2021 https://chinaenergyportal.org/en/2020-electricity-other-energy-statistics-preliminary/

- ^ "National Data" (in Chinese). Data.stats.gov.cn. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ "Chinese coal plant approvals slum after Xi climate pledge". South China Morning Post. 25 August 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ a b Yihe, Xu (1 September 2021). "China curbs coal-fired power expansion, giving way to renewables". Upstream. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ Cheng, Evelyn (29 April 2021). "China has 'no other choice' but to rely on coal power for now, official says". CNBC. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ "China generated half of global coal power in 2020: study". Deutsche Welle. 29 March 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ "Why China is struggling to wean itself from coal". www.hellenicshippingnews.com. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ a b "China's Carbon Neutral Opportunity" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2021.

- ^ Gray, Matt; Sundaresan, Sriya (April 2020). Political decisions, economic realities: The underlying operating cashflows of coal power during COVID-19 (Report). Carbon Tracker. p. 19.

- ^ How to Retire Early: Making accelerated coal phaseout feasible and just (Report). Carbon Tracker. June 2020.

- ^ China's New Growth Pathway: From the 14th Five-Year Plan to Carbon Neutrality (PDF) (Report). Energy Foundation China. December 2020. p. 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "China's new coal power spree continues as more provinces jump on the bandwagon". Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. 29 August 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ Lushan, Huang (23 November 2023). "China's new capacity payment risks locking in coal". China Dialogue. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ Kahrl, Fredrich; Lin, Jiang; Liu, Xu; Hu, Junfeng (24 September 2021). "Sunsetting coal power in China". iScience. 24 (9): 102939. Bibcode:2021iSci...24j2939K. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.102939. ISSN 2589-0042. PMC 8379489. PMID 34458696.

- ^ a b "Retired Coal-fired Power Capacity by Country / Global Coal Plant Tracker". Global Energy Monitor. 2023. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. — Global Energy Monitor's Summary of Tables (archive)

- ^ "Boom and Bust Coal / Tracking the Global Coal Plant Pipeline" (PDF). Global Energy Monitor. 5 April 2023. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2023.

- ^ "New Coal-fired Power Capacity by Country / Global Coal Plant Tracker". Global Energy Monitor. 2023. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. — Global Energy Monitor's Summary of Tables (archive)

- ^ Feng, Hao (7 April 2016). "China Puts an Emergency Stop on Coal Power Construction". The Diplomat.

- ^ Forsythe, Michael (18 January 2017). "China Cancels 103 Coal Plants, Mindful of Smog and Wasted Capacity". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ "Asian coal boom: climate threat or mirage?". Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit. 22 March 2016. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ "Beijing power companies close to bankruptcy petition for price hikes". South China Morning Post. 10 September 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Zhang, Angela Huyue (2024). High Wire: How China Regulates Big Tech and Governs Its Economy. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197682258.001.0001. ISBN 9780197682258.

- ^ "Will China save the planet or destroy it?". The Economist. 27 November 2023. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Walker, Qin (29 July 2015). "The Hidden Costs of China's Shift to Hydropower". The Diplomat. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ https://assets-global.website-files.com/5f749e4b9399c80b5e421384/60c2207c71746c499c0cd297_2021%20Hydropower%20Status%20Report%20-%20International%20Hydropower%20Association%20Reduced%20file%20size.pdf

- ^ "China | International Hydropower Association". www.hydropower.org. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ "China's Carbon Neutral Opportunity" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2021.

- ^ Hvistendahl, Mara. "China's Three Gorges Dam: An Environmental Catastrophe?". Scientific American. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ Oceans of Opportunity: Harnessing Europe’s largest domestic energy resource pp. 18–19. Ewea.org

- ^ Wind provides 1.5% of China's electricity Wind Power Monthly, 5 December 2011

- ^ "Global Wind Statistics 2014" (PDF). Gwec.net. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ "China was world's largest wind market in 2012". Renewable Energy World. 4 February 2013. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- ^ "China revises up 2015 renewable energy goals: report". Reuters. 29 August 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ Gow, David (3 February 2009). "Wind power becomes Europe's fastest growing energy source". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ "PRIS - Country Details". Pris.iaea.org. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ "2020 electricity & other energy statistics (preliminary) – China Energy Portal". 22 January 2021.

- ^ "2017 electricity & other energy statistics – China Energy Portal – 中国能源门户". 6 February 2018.

- ^ "China's solar capacity overtakes Germany in 2015, industry data show". Reuters. 21 January 2016 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ "China Overtakes Germany to Become World's Leading Solar PV Country". 22 January 2016.

- ^ "China Installed 18.6 GW of Solar PV in 2015, but Was All of It Connected?". 7 July 2016.

- ^ "China Is Adding Solar Power at a Record Pace". Bloomberg.com. 19 July 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ "Why China's energy transition is so difficult". OMFIF. 11 April 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ China's Big Push for Renewable Energy

- ^ "Solar Heat Worldwide 2014" (PDF). www.iea-shc.org. IEA Solar Heating & Cooling Programme. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ Yang, X. Jin; Hu, Hanjun; Tan, Tianwei; Li, Jinying (2016). "China's renewable energy goals by 2050". Environmental Development. 20: 83–90. Bibcode:2016EnvDe..20...83Y. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2016.10.001.

- ^ a b c Gao, Yun; Wang, Bei; Hu, Yidan; Gao, Yujie; Hu, Aolin (25 February 2024). "Development of China's natural gas: Review 2023 and outlook 2024". Natural Gas Technology and Economy. 44 (2): 166–177.

- ^ a b Guo, Hong; Cui, Jie; Li, Junhao (1 November 2022). "Biomass power generation in China: Status, policies and recommendations". Energy Reports. 2022 The 5th International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Green Energy. 8: 687–696. Bibcode:2022EnRep...8R.687G. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2022.08.072. ISSN 2352-4847.

- ^ "China's energy storage capacity using new tech almost quadrupled in 2023: NEA". South China Morning Post. 26 January 2024. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ a b Li, Weilin; Xu, Peng; Lu, Xing; Wang, Huilong; Pang, Zhihong (1 November 2016). "Electricity demand response in China: Status, feasible market schemes and pilots". Energy. 114: 981–994. Bibcode:2016Ene...114..981L. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2016.08.081. ISSN 0360-5442.

- ^ a b c "China's Demand Response in Action". www.integralnewenergy.com. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ "Demand Response in China". China Energy Storage Alliance. 24 June 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ Areddy, James (29 September 2010). "China Wants Smart Grid, But Not Too Smart". WSJ. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ Paul Hu: A New Energy Network: HVDC Development in China, September 2016

- ^ a b Curtis, Simon; Klaus, Ian (2024). The Belt and Road City: Geopolitics, Urbanization, and China's Search for a New International Order. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. doi:10.2307/jj.11589102. ISBN 9780300266900. JSTOR jj.11589102.

- ^ "中央企业_国务院国有资产监督管理委员会". Sasac.gov.cn. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ "SDIC Power Homepage". Sdicpower.com. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ "SDIC Power Holdings Co Ltd: SHA:600886 quotes & news – Google Finance". Google.com. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ Kahrl, Fredrich; Lin, Jiang; Liu, Xu; Hu, Junfeng (24 September 2021). "Sunsetting coal power in China". iScience. 24 (9): 102939. Bibcode:2021iSci...24j2939K. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.102939. ISSN 2589-0042. PMC 8379489. PMID 34458696.

- ^ "Beijing power companies close to bankruptcy petition for price hikes". South China Morning Post. 10 September 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Boom and Bust 2021: Tracking The Global Coal Plant Pipeline (Report). Global Energy Monitor. 5 April 2021.

External links

[edit]- China Electric Power Research Institute – associated with the State Grid Corporation of China

- Office of the National Energy Leading Group

- China Electrotechnical Society

- Energy Research Institute of China

- China Electric Power Database

- China's oversupply of electric power worrisome 2 January 2006 Zhang Mingquan – HK Trade Council

- China Electric Power Industry Forum Archived 31 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- China EPower Forum

KSF

KSF