English contract law

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 107 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 107 min

| Contract law |

|---|

| Formation |

| Defences |

| Interpretation |

| Dispute resolution |

| Rights of third parties |

| Breach of contract |

| Remedies |

| Quasi-contractual obligations |

| Duties of parties |

|

| Related areas of law |

| By jurisdiction |

|

| Other law areas |

| Notes |

|

English contract law is the body of law that regulates legally binding agreements in England and Wales. With its roots in the lex mercatoria and the activism of the judiciary during the Industrial Revolution, it shares a heritage with countries across the Commonwealth (such as Australia, Canada, India[1]). English contract law also draws influence from European Union law, from the United Kingdom's continuing membership in Unidroit and, to a lesser extent, from the United States.

A contract is a voluntary obligation, or set of voluntary obligations, which is enforceable by a court or tribunal. This contrasts with other areas of private law in which obligations arise as an operation of the law. For example, the law imposes a duty on individuals not to unlawfully constrain another's freedom of movement (false imprisonment) in the law of tort and the law says a person cannot hold property mistakenly transferred in the law of unjust enrichment. English law places great importance on making sure that individuals genuinely consent to the agreements that can be enforced in court, as long as those agreements comply with statutory requirements and Human Rights.

Generally, a contract is formed when one person makes an offer, and another person accepts it by communicating their assent or performing the offer's terms. If the terms are certain, and the parties can be presumed from their behaviour to have intended that the terms are binding, generally the agreement is enforceable. Some contracts, particularly for large transactions such as a sale of land, also require the formalities of signatures and witnesses and English law goes further than other European countries by requiring all parties bring something of value, known as "consideration", to a bargain as a precondition to enforce it. Contracts can be made personally or through an agent acting on behalf of a principal, if the agent acts within what a reasonable person would think they have the authority to do. In principle, English law grants people broad freedom to agree the content of a deal. Terms in an agreement are incorporated through express promises, by reference to other terms or potentially through a course of dealing between two parties. Those terms are interpreted by the courts to seek out the true intention of the parties, from the perspective of an objective observer, in the context of their bargaining environment. Where there is a gap, courts typically imply terms to fill the spaces, but also through the 20th century both the judiciary and legislature have intervened more and more to strike out surprising and unfair terms, particularly in favour of consumers, employees or tenants with weaker bargaining power.

Contract law works best when an agreement is performed, and recourse to the courts is never needed because each party knows their rights and duties. However, where an unforeseen event renders an agreement very hard, or even impossible to perform, the courts typically will construe the parties to want to have released themselves from their obligations. It may also be that one party simply breaches a contract's terms. If a contract is not substantially performed, then the innocent party is entitled to cease their own performance and sue for damages to put them in the position as if the contract were performed. They are under a duty to mitigate their own losses and cannot claim for harm that was a remote consequence of the contractual breach, but remedies in English law are footed on the principle that full compensation for all losses, pecuniary or not, should be made good. In exceptional circumstances, the law goes further to require a wrongdoer to make restitution for their gains from breaching a contract, and may demand specific performance of the agreement rather than monetary compensation. It is also possible that a contract becomes voidable, because, depending on the specific type of contract, one party failed to make adequate disclosure or they made misrepresentations during negotiations.

Unconscionable agreements can be escaped where a person was under duress or undue influence or their vulnerability was being exploited when they ostensibly agreed to a deal. Children, mentally incapacitated people, and companies whose representatives are acting wholly outside their authority, are protected against having agreements enforced against them where they lacked the real capacity to make a decision to enter an agreement. Some transactions are considered illegal, and are not enforced by courts because of a statute or on grounds of public policy. In theory, English law attempts to adhere to a principle that people should only be bound when they have given their informed and true consent to a contract.

History

[edit]

The modern law of contract is primarily a creature of the Industrial Revolution and the social legislation of the 20th century. However, the foundations of all European contract law are traceable to obligations in Ancient Athenian and Roman law,[2] while the formal development of English law began after the Norman Conquest of 1066. William the Conqueror created a common law across England, but throughout the Middle Ages the court system was minimal. Access to the courts, in what are now considered contractual disputes, was consciously restricted to a privileged few through onerous requirements of pleading, formalities and court fees. In the local and manorial courts, according to English law's first treatise by Ranulf de Glanville in 1188, if people disputed the payment of a debt they, and witnesses, would attend court and swear oaths (called a wager of law).[3] They risked perjury if they lost the case, and so this was strong encouragement to resolve disputes elsewhere.

The royal courts, fixed to meet in London by Magna Carta, accepted claims for "trespass on the case" (more like a tort today). A jury would be called, and no wager of law was needed, but some breach of the King's peace had to be alleged. Gradually, the courts allowed claims where there had been no real trouble, no tort with "force of arms" (vi et armis), but it was still necessary to put this in the pleading. For instance, in 1317 one Simon de Rattlesdene alleged he was sold a tun of wine that was contaminated with salt water and, quite fictitiously, this was said to be done "with force and arms, namely with swords and bows and arrows".[4] The Court of Chancery and the King's Bench slowly started to allow claims without the fictitious allegation of force and arms from around 1350. An action for simple breach of a covenant (a solemn promise) had required production of formal proof of the agreement with a seal. However, in The Humber Ferryman's case a claim was allowed, without any documentary evidence, against a ferryman who dropped a horse overboard that he was contracted to carry across the River Humber.[5] Despite this liberalization, in the 1200s a threshold of 40 shillings for a dispute's value had been created. Though its importance tapered away with inflation over the years, it foreclosed court access to most people.[6] Moreover, freedom to contract was firmly suppressed among the peasantry. After the Black Death, the Statute of Labourers 1351 prevented any increase in workers' wages fuelling, among other things, the Peasants' Revolt of 1381.

Increasingly, the English law on contractual bargains was affected by its trading relations with northern Europe, particularly since Magna Carta had guaranteed merchants "safe and secure" exit and entry to England "for buying and selling by the ancient rights and customs, quit from all evil tolls".[7] In 1266 King Henry III had granted the Hanseatic League a charter to trade in England. The "Easterlings" who came by boats brought goods and money that the English called "Sterling",[8] and standard rules for commerce that formed a lex mercatoria, the laws of the merchants. Merchant custom was most influential in the coastal trading ports like London, Boston, Hull and King's Lynn. While the courts were hostile to restraints on trade, a doctrine of consideration was forming, so that to enforce any obligation something of value needed to be conveyed.[9] Some courts remained sceptical that damages might be awarded purely for a broken agreement (that was not a sealed covenant).[10] Other disputes allowed a remedy. In Shepton v Dogge[11] a defendant had agreed in London, where the City courts' custom was to allow claims without covenants under seal, to sell 28 acres of land in Hoxton. Although the house itself was outside London at the time, in Middlesex, a remedy was awarded for deceit, but essentially based on a failure to convey the land.

The resolution of these restrictions came shortly after 1585, when a new Court of Exchequer Chamber was established to hear common law appeals. In 1602, in Slade v Morley,[12] a grain merchant named Slade claimed that Morley had agreed to buy wheat and rye for £16, but then had backed out. Actions for debt were in the jurisdiction of the Court of Common Pleas, which had required both (1) proof of a debt, and (2) a subsequent promise to repay the debt, so that a finding of deceit (for non-payment) could be made against a defendant.[13] But if a claimant wanted to simply demand payment of the contractual debt (rather than a subsequent promise to pay) he could have to risk a wager of law. The judges of the Court of the King's Bench was prepared to allow "assumpsit" actions (for obligations being assumed) simply from proof of the original agreement.[14] With a majority in the Exchequer Chamber, after six years Lord Popham CJ held that "every contract importeth in itself an Assumpsit".[15] Around the same time the Common Pleas indicated a different limit for contract enforcement in Bret v JS,[16] that "natural affection of itself is not a sufficient consideration to ground an assumpsit" and there had to be some "express quid pro quo".[17] Now that wager of law, and sealed covenants were essentially unnecessary, the Statute of Frauds 1677 codified the contract types that were thought should still require some form. Over the late 17th and 18th centuries Sir John Holt,[18] and then Lord Mansfield actively incorporated the principles of international trade law and custom into English common law as they saw it: principles of commercial certainty, good faith,[19] fair dealing, and the enforceability of seriously intended promises.[20] As Lord Mansfield held, "Mercantile law is not the law of a particular country but the law of all nations",[21] and "the law of merchants and the law of the land is the same".[20]

'governments do not limit their concern with contracts to a simple enforcement. They take upon themselves to determine what contracts are fit to be enforced.... once it is admitted that there are any engagements which for reasons of expediency the law ought not to enforce, the same question is necessarily opened with respect to all engagements. Whether, for example, the law should enforce a contract to labour, when the wages are too low or the hours of work too severe: whether it should enforce a contract by which a person binds himself to remain, for more than a very limited period, in the service of a given individual.... Every question which can possibly arise as to the policy of contracts, and of the relations which they establish among human beings, is a question for the legislator; and one which he cannot escape from considering, and in some way or other deciding.'

Over the industrial revolution, English courts became more and more wedded to the concept of "freedom of contract". It was partly a sign of progress, as the vestiges of feudal and mercantile restrictions on workers and businesses were lifted, a move of people (at least in theory) from "status to contract".[22] On the other hand, a preference for laissez faire thought concealed the inequality of bargaining power in multiple contracts, particularly for employment, consumer goods and services, and tenancies. At the centre of the general law of contracts, captured in nursery rhymes like Robert Browning's Pied Piper of Hamelin in 1842, was the fabled notion that if people had promised something "let us keep our promise".[23] But then, the law purported to cover every form of agreement, as if everybody had the same degree of free will to promise what they wanted. Though many of the most influential liberal thinkers, especially John Stuart Mill, believed in multiple exceptions to the rule that laissez faire was the best policy,[24] the courts were suspicious of interfering in agreements, whoever the parties were. In Printing and Numerical Registering Co v Sampson Sir George Jessel MR proclaimed it a "public policy" that "contracts when entered into freely and voluntarily shall be held sacred and shall be enforced by Courts of justice."[25] The same year, the Judicature Act 1875 merged the Courts of Chancery and common law, with equitable principles (such as estoppel, undue influence, rescission for misrepresentation and fiduciary duties or disclosure requirements in some transactions) always taking precedence.[26]

The essential principles of English contract law, however, remained stable and familiar, as an offer for certain terms, mirrored by an acceptance, supported by consideration, and free from duress, undue influence or misrepresentation, would generally be enforceable. The rules were codified and exported across the British Empire, as for example in the Indian Contract Act 1872.[27] Further requirements of fairness in exchanges between unequal parties, or general obligations of good faith and disclosure were said to be unwarranted because it was urged by the courts that liabilities "are not to be forced upon people behind their backs".[28] Parliamentary legislation, outside general codifications of commercial law like the Sale of Goods Act 1893, similarly left people to the harsh realities of the market and "freedom of contract". This only changed when the property qualifications to vote for members of parliament were reduced and eliminated, as the United Kingdom slowly became more democratic.[29]

Over the 20th century, legislation and changes in court attitudes effected a wide-ranging reform of 19th century contract law.[32] First, specific types of non-commercial contract were given special protection where "freedom of contract" appeared far more on the side of large businesses.[33] Consumer contracts came to be regarded as "contracts of adhesion" where there was no real negotiation and most people were given "take it or leave it" terms.[34] The courts began by requiring entirely clear information before onerous clauses could be enforced,[35] the Misrepresentation Act 1967 switched the burden of proof onto business to show misleading statements were not negligent, and the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 created the jurisdiction to scrap contract terms that were "unreasonable", considering the bargaining power of the parties. Collective bargaining by trade unions and a growing number of employment rights carried the employment contract into an autonomous field of labour law where workers had rights, like a minimum wage,[36] fairness in dismissal,[37] the right to join a union and take collective action,[38] and these could not be given up in a contract with an employer. Private housing was subject to basic terms, such as the right to repairs, and restrictions on unfair rent increases, though many protections were abolished during the 1980s.[39] Nevertheless, the scope of the general law of contract had been reduced. It meant that most contracts made by people on an ordinary day were shielded from the power of corporations to impose whatever terms they chose in selling goods and services, at work, and in people's home. Nevertheless, classical contract law remained at the foundation of those specific contracts, unless particular rights were given by the courts or Parliament. Internationally, the UK had joined the European Union, which aimed to harmonize significant parts of consumer and employment law across member states. Moreover, with increasing openness of markets commercial contract law was receiving principles from abroad. Both the Principles of European Contract Law, the UNIDROIT Principles of International Commercial Contracts, and the practice of international commercial arbitration was reshaping thinking about English contract principles in an increasingly globalized economy.

Formation

[edit]

In its essence a contract is an agreement which the law recognises as giving rise to enforceable obligations.[40] As opposed to tort and unjust enrichment, contract is the part of the law of obligations which deals with voluntary undertakings. It places a high priority on ensuring that only bargains to which people have given their true consent will be enforced by the courts. While it is not always clear when people have truly agreed in a subjective sense, English law takes the view that when one person objectively manifests their consent to a bargain, they will be bound.[41] However, not all agreements, even if they are relatively certain in subject matter, are considered enforceable. There is a rebuttable presumption that people do not wish to later have legal enforcement of agreements made socially or domestically. The general rule is that contracts require no prescribed form, such as being in writing, except where statute requires it, usually for large deals like the sale of land.[42] In addition and in contrast to civil law systems, English common law carried a general requirement that all parties, in order to have standing to enforce an agreement, must have brought something of value, or "consideration" to the bargain. This old rule is full of exceptions, particularly where people wished to vary their agreements, through case law and the equitable doctrine of promissory estoppel. Moreover, statutory reform in the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 allows third parties to enforce the benefit of an agreement that they had not necessarily paid for so long as the original parties to a contract consented to them being able to do so.

Agreement

[edit]The formal approach of English courts is that agreement exists when an offer is mirrored by an unequivocal acceptance of the terms on offer. Whether an offer has been made, or it has been accepted, is an issue courts determine by asking what a reasonable person would have thought was intended.[43] Offers are distinguished from "invitations to treat" (or an invitatio ad offerendum, the invitation of an offer) which cannot be simply accepted by the other party. Traditionally, English law has viewed the display of goods in a shop, even with a price tag, as an invitation to treat,[44] so that when a customer takes the product to the till it is she who is making the offer, and the shopkeeper may refuse to sell. Similarly, and as a very general rule, an advertisement,[45] the invitation to make a bid at an auction with a reserve price,[46] or the invitation to submit a tender bid are not considered offers. On the other hand, a person inviting tenders may fall under a duty to consider the submissions if they arrive before the deadline, so the bidder (even though there is no contract) could sue for damages if his bid is never considered.[47] An auctioneer who publicizes an auction as being without a reserve price falls under a duty to accept the highest bid.[48] An automated vending machine constitutes a standing offer,[49] and a court may construe an advertisement, or something on display like a deckchair, to be a serious offer if a customer would be led to believe they were accepting its terms by performing an action.[50] Statute imposes criminal penalties for businesses that engage in misleading advertising, or not selling products at the prices they display in store,[51] or unlawfully discriminating against customers on grounds of race, gender, sexuality, disability, belief or age.[52] The Principles of European Contract Law article 2:201 suggests that most EU member states count a proposal to supply any good or service by a professional as an offer.

Once an offer is made, the general rule is the offeree must communicate her acceptance in order to have a binding agreement.[53] Notification of acceptance must actually reach a point where the offeror could reasonably be expected to know, although if the recipient is at fault, for instance, by not putting enough ink in their fax machine for a message arriving in office hours to be printed, the recipient will still be bound.[54] This goes for all methods of communication, whether oral, by phone, through telex, fax or email,[55] except for the post. Acceptance by letter takes place when the letter is put in the postbox. The postal exception is a product of history,[56] and does not exist in most countries.[57] It only exists in English law so long as it is reasonable to use the post for a reply (e.g. not in response to an email), and its operation would not create manifest inconvenience and absurdity (e.g. the letter goes missing).[58] In all cases it is possible for the negotiating parties to stipulate a prescribed mode of acceptance.[59] It is not possible for an offeror to impose an obligation on the offeree to reject the offer without her consent.[60] However, it is clear that people can accept through silence, firstly, by demonstrating through their conduct that they accept. In Brogden v Metropolitan Railway Company,[61] although the Metropolitan Railway Company had never returned a letter from Mr Brogden formalizing a long-term supply arrangement for Mr Brogden's coal, they had conducted themselves for two years as if it were in effect, and Mr Brogden was bound. Secondly, the offeror may waive the need for communication of acceptance, either expressly, or implicitly, as in Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company.[62] Here a quack medicine company advertised its "smoke ball", stating that if a customer found it did not cure them of the flu after using it thrice daily for two weeks, they would get £100. After noting the advertisement was serious enough to be an offer, not mere puff or an invitation to treat, the Court of Appeal held the accepting party only needed to use the smokeball as prescribed to get the £100. Although the general rule was to require communication of acceptance, the advertisement had tacitly waived the need for Mrs Carlill, or anyone else, to report her acceptance first. In other cases, such as where a reward is advertised for information, the only requirement of the English courts appears to be knowledge of the offer.[63] Where someone makes such a unilateral offer, they fall under a duty to not revoke it once someone has begun to act on the offer.[64] Otherwise an offer may always be revoked before it is accepted. The general rule is that revocation must be communicated, even if by post,[65] although if the offerree hears about the withdrawal from a third party, this is as good as a withdrawal from the offeror himself.[66] Finally, an offer can be "killed off" if, rather than a mere inquiry for information,[67] someone makes a counter offer. So in Hyde v Wrench,[68] when Wrench offered to sell his farm for £1000, and Hyde replied that he would buy it for £950 and Wrench refused, Hyde could not then change his mind and accept the original £1000 offer.

While the model of an offer mirroring acceptance makes sense to analyse almost all agreements, it does not fit in some cases. In The Satanita[69] the rules of a yacht race stipulated that the yachtsmen would be liable, beyond limits set in statute, to pay for all damage to other boats. The Court of Appeal held that there was a contract to pay arising from the rules of the competition between The Satanita's owner and the owner of Valkyrie II, which he sank, even though there was no clear offer mirrored by a clear acceptance between the parties at any point. Along with a number of other critics,[70] in a series of cases Lord Denning MR proposed that English law ought to abandon its rigid attachment to offer and acceptance in favour of a broader rule, that the parties need to be in substantial agreement on the material points in the contract. In Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-O Corp Ltd[71] this would have meant that during a "battle of forms" two parties were construed as having material agreement on the buyer's standard terms, and excluding a price variation clause, although the other court members reached the same view on ordinary analysis. In Gibson v Manchester CC[72] he would have come to a different result to the House of Lords, by allowing Mr Gibson to buy his house from the council, even though the council's letter stated it "should not be regarded as a firm offer". This approach would potentially give greater discretion to a court to do what appears appropriate at the time, without being tied to what the parties may have subjectively intended, particularly where those intentions obviously conflicted.

In a number of instances, the courts avoid enforcement of contracts where, although there is a formal offer and acceptance, little objective agreement exists otherwise. In Hartog v Colin & Shields,[73] where the seller of some Argentine hare skins quoted his prices far below what previous negotiations had suggested, the buyer could not enforce the agreement because any reasonable person would have known the offer was not serious, but a mistake.[74] Moreover, if two parties think they reach an agreement, but their offer and acceptance concerns two entirely different things, the court will not enforce a contract. In Raffles v Wichelhaus,[75] Raffles thought he was selling cotton aboard one ship called The Peerless, which would arrive from Bombay in Liverpool in December, but Wichelhaus thought he was buying cotton aboard another ship called The Peerless that would arrive in September. The court held there was never consensus ad idem (Latin: "agreement to the [same] thing"). Where agreements totally fail, but one party has performed work at another's request, relying on the idea that there will be a contract, that party may make a claim for the value of the work done, or quantum meruit.[76] Such a restitution claim allows recovery for the expense the claimant goes to, but will not cover her expectation of potential profits, because there is no agreement to be enforced.

Certainty and enforceability

[edit]While agreement is the basis for all contracts, not all agreements are enforceable. A preliminary question is whether the contract is reasonably certain in its essential terms, or essentialia negotii, such as price, subject matter and the identity of the parties. Generally the courts endeavour to "make the agreement work", so in Hillas & Co Ltd v Arcos Ltd,[77] the House of Lords held that an option to buy softwood of "fair specification" was sufficiently certain to be enforced, when read in the context of previous agreements between the parties. However the courts do not wish to "make contracts for people", and so in Scammell and Nephew Ltd v Ouston,[78] a clause stipulating the price of buying a new van as "on hire purchase terms" for two years was held unenforceable because there was no objective standard by which the court could know what price was intended or what a reasonable price might be.[79] Similarly, in Baird Textile Holdings Ltd v M&S plc[80] the Court of Appeal held that because the price and quantity to buy would be uncertain, in part, no term could be implied for M&S to give reasonable notice before terminating its purchasing agreement. Controversially, the House of Lords extended this idea by holding an agreement to negotiate towards a future contract in good faith is insufficiently certain to be enforceable.[81]

While many agreements can be certain, it is by no means certain that in the case of social and domestic affairs people want their agreements to be legally binding. In Balfour v Balfour[83] Atkin LJ held that Mr Balfour's agreement to pay his wife £30 a month while he worked in Ceylon should be presumed unenforceable, because people do not generally intend such promises in the social sphere to create legal consequences. Similarly, an agreement between friends at a pub, or a daughter and her mother will fall into this sphere,[84] but not a couple who are on the verge of separation,[85] and not friends engaged in big transactions, particularly where one side relies heavily to their detriment on the assurances of the other.[86] This presumption of unenforceability can always be rebutted by express agreement otherwise, for instance by writing the deal down. By contrast, agreements made among businesses are almost conclusively presumed to be enforceable.[87] But again, express words, such as "This arrangement... shall not be subject to legal jurisdiction in the law courts" will be respected.[88] In one situation, statute presumes that collective agreements between a trade union and an employer are not intended to create legal relations, ostensibly to keep excessive litigation away from UK labour law.[89]

In a limited number of cases, an agreement will be unenforceable unless it meets a certain form prescribed by statute. While contracts can be generally made without formality, some transactions are thought to require form either because it makes a person think carefully before they bind themselves to an agreement, or merely that it serves as clear evidence.[90] This goes typically for large engagements, including the sale of land,[42] a lease of property over three years,[91] a consumer credit agreement,[92] and a bill of exchange.[93] A contract for guarantee must also, at some stage, be evidenced in writing.[94] Finally, English law takes the approach that a gratuitous promise, as a matter of contract law, is not legally binding. While a gift that is delivered will transfer property irrevocably, and while someone may always bind themselves to a promise without anything in return to deliver a thing in future if they sign a deed that is witnessed,[95] a simple promise to do something in future can be revoked. This result is reached, with some complexity, through a peculiarity of English law called the doctrine of consideration.

Consideration and estoppel

[edit]Consideration is an additional requirement in English law before a contract is enforceable.[96] A person wishing to enforce an agreement must show that they have brought something to the bargain which has "something of value in the eyes of the law", either by conferring a benefit on another person or incurring a detriment at their request.[97] In practice this means not simple gratitude or love,[98] not things already done in the past, and not promising to perform a pre-existing duty unless performance takes place for a third party.[99] Metaphorically, consideration is "the price for which the promise is bought".[100] It is contentious in the sense that it gives rise to a level of complexity that legal systems which do not take their heritage from English law simply do not have.[101] In reality the doctrine of consideration operates in a very small scope, and creates few difficulties in commercial practice. After reform in the United States,[102] especially the Restatement of Contracts §90 which allows all promises to bind if it would otherwise lead to "injustice", a report in 1937 by the Law Revision Committee, Statute of Frauds and the Doctrine of Consideration,[103] proposed that promises in writing, for past consideration, for part payments of debt, promising to perform pre-existing obligations, promising to keep an offer open, and promises that another relies on to their detriment should all be binding. The report was never enacted in legislation, but almost all of its recommendations have been put into effect through case law since,[104] albeit with difficulty.

When a contract is formed, good consideration is needed, and so a gratuitous promise is not binding. That said, while consideration must be of sufficient value in the law's eyes, it need not reflect an adequate price. Proverbially, one may sell a house for as little as a peppercorn, even if the seller "does not like pepper and will throw away the corn."[106] This means the courts do not generally enquire into the fairness of the exchange,[107] unless there is statutory regulation[108] or (in specific contexts such as for consumers, employment, or tenancies) there are two parties of unequal bargaining power.[109] Another difficulty is that consideration for a deal was said not to exist if the thing given was an act done before the promise, such as promising to pay off a loan for money already used to educate a girl.[110] In this situation the courts have long shown themselves willing to hold that the thing done was implicitly relying on the expectation of a reward.[111] More significant problems arise where parties to a contract wish to vary its terms. The old rule, predating the development of the protections in the law of economic duress, was that if one side merely promises to perform a duty which she had already undertaken in return for a higher price, there is no contract.[112] However, in the leading case of Williams v Roffey Bros & Nicholls (Contractors) Ltd,[113] the Court of Appeal held that it would be more ready to construe someone performing essentially what they were bound to do before as giving consideration for the new deal if they conferred a "practical benefit" on the other side.[114] So, when Williams, a carpenter, was promised by Roffey Bros, the builders, more money to complete work on time, it was held that because Roffey Bros would avoid having to pay a penalty clause for late completion of its own contract, would potentially avoid the expense of litigation and had a slightly more sensible mechanism for payments, these were enough. Speaking of consideration, Russell LJ stated that, "courts nowadays should be more ready to find its existence... where the bargaining powers are not unequal and where the finding of consideration reflects the true intention of the parties." In other words, in the context of contractual variations, the definition of consideration has been watered down. However, in one situation the "practical benefit" analysis cannot be invoked, namely where the agreed variation is to reduce debt repayments. In Foakes v Beer,[115] the House of Lords held that even though Mrs Beer promised Mr Foakes he could pay back £2090 19s by instalment and without interest, she could subsequently change her mind and demand the whole sum. Despite Lord Blackburn registering a note of dissent in that case and other doubts,[116] the Court of Appeal held in Re Selectmove Ltd,[117] that it was bound by the precedent of the Lords and could not deploy the "practical benefit" reasoning of Williams for any debt repayment cases.

However, consideration is a doctrine deriving from the common law, and can be suspended under the principles of equity. Historically, England had two separate court systems, and the Courts of Chancery which derived their ultimate authority from the King via the Lord Chancellor, took precedence over the common law courts. So does its body of equitable principles since the systems were merged in 1875.[118] The doctrine of promissory estoppel holds that when one person gives an assurance to another, the other relies on it and it would be inequitable to go back on the assurance, that person will be estopped from doing so: an analogue of the maxim that nobody should profit from their own wrong (nemo auditur propriam turpitudinem allegans). So in Hughes v Metropolitan Railway Co[119] the House of Lords held that a tenant could not be ejected by the landlord for failing to keep up with his contractual repair duties because starting negotiations to sell the property gave the tacit assurance that the repair duties were suspended. And in Central London Properties Ltd v High Trees House Ltd[120] Denning J held that a landlord would be estopped from claiming normal rent during the years of World War II because he had given an assurance that half rent could be paid till the war was done. The Court of Appeal went even further in a recent debt repayment case, Collier v P&M J Wright (Holdings) Ltd.[121] Arden LJ argued that a partner who had been assured he was only liable to repay one third of the partnership's debts, rather than be jointly and severally liable for the whole, had relied on the assurance by making repayments, and it was inequitable for the finance company to later demand full repayment of the debt. Hence, promissory estoppel could circumvent the common law rule of Foakes. Promissory estoppel, however, has been thought to be incapable of raising an independent cause of action, so that one may only plead another party is estopped from enforcing their strict legal rights as a "shield", but cannot bring a cause of action out of estoppel as a "sword".[122] In Australia, this rule was relaxed in Walton Stores (Interstate) Ltd v Maher, where Mr Maher was encouraged to believe he would have a contract to sell his land, and began knocking down his existing building before Walton Stores finally told him they did not wish to complete. Mr Maher got generous damages covering his loss (i.e. reliance damages, but seemingly damages for loss of expectations as if there were a contract).[123] Yet, where an assurance concerns rights over property, a variant "proprietary estoppel" does allow a claimant to plead estoppel as a cause of action. So in Crabb v Arun District Council, Mr Crabbe was assured he would have the right to an access point to his land by Arun District Council, and relying on that he sold off half the property where the only existing access point was. The council was estopped from not doing what they said they would.[124] Given the complex route of legal reasoning to reach simple solutions, it is unsurprising that a number of commentators,[125] as well as the Principles of European Contract Law have called for simple abandonment of the doctrine of consideration, leaving the basic requirements of agreement and an intention to create legal relations. Such a move would also dispense with the need for the common law doctrine of privity.

Privity

[edit]The common law of privity of contract is a sub-rule of consideration because it restricts who can enforce an agreement to those who have brought consideration to the bargain. In an early case, Tweddle v Atkinson, it was held that because a son had not given any consideration for his father in law's promise to his father to pay the son £200, he could not enforce the promise.[126] Given the principle that standing to enforce an obligation should reflect whoever has a legitimate interest in its performance, a 1996 report by the Law Commission entitled Privity of Contract: Contracts for the Benefit of Third Parties, recommended that while courts should be left free to develop the common law, some of the more glaring injustices should be removed.[127] This led to the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999. Under section 1, a third party may enforce an agreement if it purports to confer a benefit on the third party, either individually or a member as a class, and there is no expressed stipulation that the person was not intended to be able to enforce it.[128] In this respect there is a strong burden on the party claiming enforcement was not intended by a third party.[129] A third party has the same remedies available as a person privy to an agreement, and can enforce both positive benefits, or limits on liability, such as an exclusion clause.[130] The rights of a third party can then only be terminated or withdrawn without her consent if it is reasonably foreseeable that she would rely upon them.[131]

The 1999 Act's reforms mean a number of old cases would be decided differently today. In Beswick v Beswick[133] while the House of Lords held that Mrs Beswick could specifically enforce a promise of her nephew to her deceased husband to pay her £5 weekly in her capacity as administratrix of the will, the 1999 Act would also allow her to claim as a third party. In Scruttons Ltd v Midland Silicones Ltd[134] it would have been possible for a stevedore firm to claim the benefit of a limitation clause in a contract between a carrier and the owner of a damaged drum of chemicals. Lord Denning dissented, arguing for abolition of the rule, and Lord Reid gave an opinion that if a bill of lading expressly conferred the benefit of a limitation on the stevedores, the stevedores give authority to the carrier to do that, and "difficulties about consideration moving from the stevedore were overcome" then the stevedores could benefit. In The Eurymedon,[135] Lord Reid's inventive solution was applied where some stevedores similarly wanted the benefit of an exclusion clause after dropping a drilling machine, the consideration being found as the stevedores performing their pre-existing contractual duty for the benefit of the third party (the drilling machine owner). Now none of this considerably technical analysis is required,[136] given that any contract purporting to confer a benefit on a third party may in principle be enforced by the third party.[137]

Given that the 1999 Act preserves the promisee's right to enforce the contract as it stood at common law,[138] an outstanding issue is to what extent a promisee can claim damages for a benefit on behalf of a third party, if he has suffered no personal loss. In Jackson v Horizon Holidays Ltd,[139] Lord Denning MR held that a father could claim damages for disappointment (beyond the financial cost) of a terrible holiday experience on behalf of his family. However, a majority of the House of Lords in Woodar Investment Development Ltd v Wimpey Construction UK Ltd[140] disapproved any broad ability of a party to a contract to claim damages on behalf of a third party, except perhaps in a limited set of consumer contracts. There is disagreement about whether this will remain the case.[141] Difficulties also remain in cases involving houses built with defects, which are sold to a buyer, who subsequently sells to a third party. It appears that neither the initial buyer can claim on behalf of the third party, and nor will the third party be able to claim under the 1999 Act, as they will typically not be identified by the original contract (or known) in advance.[142] Apart from this instance relating to tort, in practice the doctrine of privity is entirely ignored in numerous situations, throughout the law of trusts and agency.

Construction

[edit]

If an enforceable agreement – a contract – exists, the details of the contract's terms matter if one party has allegedly broken the agreement. A contract's terms are what was promised. Yet it is up to the courts to construe evidence of what the parties said before a contract's conclusion, and construe the terms agreed. Construction of the contract starts with the express promises people make to one another, but also with terms found in other documents or notices that were intended to be incorporated. The general rule is that reasonable notice of the term is needed, and more notice is needed for an onerous term. The meaning of those terms must then be interpreted, and the modern approach is to construe the meaning of an agreement from the perspective of a reasonable person with knowledge of the whole context. The courts, as well as legislation, may also imply terms into contracts generally to 'fill gaps' as necessary to fulfil the reasonable expectations of the parties, or as necessary incidents to specific contracts. English law had, particularly in the late 19th century, adhered to the laissez faire principle of "freedom of contract" so that, in the general law of contract, people can agree to whatever terms or conditions they choose. By contrast, specific contracts, particularly for consumers, employees or tenants were built to carry a minimum core of rights, mostly deriving from statute, that aim to secure the fairness of contractual terms. The evolution of case law in the 20th century generally shows an ever-clearer distinction between general contracts among commercial parties and those between parties of unequal bargaining power,[145] since in these groups of transaction true choice is thought to be hampered by lack of real competition in the market. Hence, some terms can be found to be unfair under statutes such as the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 or Part 2 of the Consumer Rights Act 2015 and can be removed by the courts, with the administrative assistance of the Competition and Markets Authority.

Incorporation of terms

[edit]The promises offered by one person to another are the terms of a contract, but not every representation before an acceptance will always count as a term. The basic rule of construction is that a representation is a term if it looked like it was "intended" to be from the viewpoint of a reasonable person.[146] It matters how much importance is attached to the term by the parties themselves, but also as a way to protect parties of lesser means, the courts added that someone who is in a more knowledgeable position will be more likely to be taken to have made a promise, rather than a mere representation. In Oscar Chess Ltd v Williams[147] Mr Williams sold a Morris car to a second hand dealer and wrongly (but in good faith, relying on a forged log-book) said it was a 1948 model when it was really from 1937. The Court of Appeal held that the car dealer could not later claim breach of contract because they were in a better position to know the model. By contrast, in Dick Bentley Productions Ltd v Harold Smith (Motors) Ltd[148] the Court of Appeal held that when a car dealer sold a Bentley to a customer, mistakenly stating it had done 20,000 miles when the true figure was 100,000 miles, this was intended to become a term because the car dealer was in a better position to know. A misrepresentation may also generate the right to cancel (or "rescind") the contract and claim damages for "reliance" losses (as if the statement had not been made, and so to get one's money back). But if the representation is also a contract term a claimant may also get damages reflecting "expected" profits (as if the contract were performed as promised), though often the two measures coincide.

When a contract is written down, there is a basic presumption that the written document will contain terms of an agreement,[150] and when commercial parties sign documents every term referred to in the document binds them,[151] unless the term is found to be unfair, the signed document is merely an administrative paper, or under the very limited defence of non est factum.[152] The rules differ in principle for employment contracts,[153] and consumer contracts,[154] or wherever a statutory right is engaged,[155] and so the signature rule matters most in commercial dealings, where businesses place a high value on certainty. If a statement is a term, and the contracting party has not signed a document, then terms may be incorporated by reference to other sources, or through a course of dealing. The basic rule, set out in Parker v South Eastern Railway Company,[149] is that reasonable notice of a term is required to bind someone. Here Mr Parker left his coat in the Charing Cross railway station cloakroom and was given a ticket that on the back said liability for loss was limited to £10. The Court of Appeal sent this back to trial for a jury (as existed at the time) to determine. The modern approach is to add that if a term is particularly onerous, greater notice with greater clarity ought to be given. Denning LJ in J Spurling Ltd v Bradshaw[156] famously remarked that "Some clauses which I have seen would need to be printed in red ink on the face of the document with a red hand pointing to it before the notice could be held to be sufficient." In Thornton v Shoe Lane Parking Ltd[157] a car park ticket referring to a notice inside the car park was insufficient to exclude the parking lot's liability for personal injury of customers on its premises. In Interfoto Picture Library Ltd v Stiletto Ltd[158] Bingham LJ held that a notice inside a jiffy bag of photographic transparencies about a fee for late return of the transparencies (which would have totalled £3,783.50 for 47 transparencies after only a month) was too onerous a term to be incorporated without clear notice. By contrast in O'Brien v MGN Ltd[159] Hale LJ held that the failure of the Daily Mirror to say in every newspaper that if there were too many winners in its free draw for £50,000 that there would be another draw was not so onerous on the disappointed "winners" as to prevent incorporation of the term. It can also be that a regular and consistent course of dealings between two parties lead the terms from previous dealings to be incorporated into future ones. In Hollier v Rambler Motors Ltd[160] the Court of Appeal held that Mr Hollier, whose car was burnt in a fire caused by a careless employee at Rambler Motors' garage, was not bound by a clause excluding liability for "damage caused by fire" on the back of an invoice which he had seen three or four times in visits over the last five years. This was not regular or consistent enough. But in British Crane Hire Corporation Ltd v Ipswich Plant Hire Ltd[161] Lord Denning MR held that a company hiring a crane was bound by a term making them pay for expenses of recovering the crane when it sank into marshland, after only one prior dealing. Of particular importance was the equal bargaining power of the parties.[162]

Interpretation

[edit]

Once it is established which terms are incorporated into an agreement, their meaning must be determined. Since the introduction of legislation regulating unfair terms, English courts have become firmer in their general guiding principle that agreements are construed to give effect to the intentions of the parties from the standpoint of a reasonable person. This changed significantly from the early 20th century, when English courts had become enamoured with a literalist theory of interpretation, championed in part by Lord Halsbury.[164] As greater concern grew around the mid-20th century over unfair terms, and particularly exclusion clauses, the courts swung to the opposite position, utilizing heavily the doctrine of contra proferentem. Ambiguities in clauses excluding or limiting one party's liability would be construed against the person relying on it. In the leading case, Canada Steamship Lines Ltd v R[165] the Crown's shed in Montreal harbour burnt down, destroying goods owned by Canada Steamship lines. Lord Morton held that a clause in the contract limiting the Crown's excluding liability for "damage... to... goods... being... in the said shed" was not enough to excuse it from liability for negligence because the clause could also be construed as referring to strict liability under another contract clause. It would exclude that instead. Some judges, and in particular Lord Denning wished to go further by introducing a rule of "fundamental breach of contract" whereby no liability for very serious breaches of contract could be excluded at all.[166] While the rules remain ready for application where statute may not help, such hostile approaches to interpretation[167] were generally felt to run contrary to the plain meaning of language.[168]

Reflecting the modern position since unfair terms legislation was enacted,[169] the most quoted passage in English courts on the canons of interpretation is found in Lord Hoffmann's judgment in ICS Ltd v West Bromwich BS.[163] Lord Hoffmann restated the law that a document's meaning is what it would mean (1) to a reasonable person (2) with knowledge of the context, or the whole matrix of fact (3) except prior negotiations (4) and meaning does not follow what the dictionary says but meaning understood from its context (5) and the meaning should not contradict common sense. The objective is always to give effect to the intentions of the parties.[170] While it remains the law for reasons of litigation cost,[171] there is some contention over how far evidence of prior negotiations should be excluded by the courts.[172] It appears increasingly clear that the courts may adduce evidence of negotiations where it would clearly assist in construing the meaning of an agreement.[173] This approach to interpretation has some overlap with the right of the parties to seek "rectification" of a document, or requesting from a court to read a document not literally but with regard to what the parties can otherwise show was really intended.[174]

Implied terms

[edit]"The foundation of contract is the reasonable expectation, which the person who promises raises in the person to whom he binds himself; of which the satisfaction may be exerted by force."

Part of the process of construction includes the courts and statute implying terms into agreements.[175] Courts imply terms, as a general rule, when the express terms of a contract leave a gap to be filled. Given their basic attachment to contractual freedom, the courts are reluctant to override express terms for contracting parties.[176] This is especially true where the contracting parties are large and sophisticated businesses who have negotiated, often with extensive legal input, comprehensive and detailed contract terms between them.. Legislation can also be a source of implied terms, and may be overridden by agreement of the parties, or have a compulsory character.[177] For contracts in general, individualized terms are implied (terms "implied in fact") to reflect the "reasonable expectations of the parties", and like the process of interpretation, implication of a term of a commercial contract must follow from its commercial setting.[178] In Equitable Life Assurance Society v Hyman the House of Lords held (in a notorious decision) that "guaranteed annuity rate" policy holders of the life insurance company could not have their bonus rates lowered by the directors, when the company was in financial difficulty, if it would undermine all the policy holders' "reasonable expectations". Lord Steyn said that a term should be implied in the policy contract that the directors' discretion was limited, as this term was "strictly necessary... essential to give effect to the reasonable expectations of the parties".[179] This objective, contextual formulation of the test for individualized implied terms represents a shift from the older and subjective formulation of the implied term test, asking like an "officious bystander" what the parties "would have contracted for" if they had applied their minds to a gap in the contract.[180] In AG of Belize v Belize Telecom Ltd, Lord Hoffmann in the Privy Council added that the process of implication is to be seen as part of the overall process of interpretation: designed to fulfill the reasonable expectations of the parties in their context.[181] The custom of the trade may also be a source of an implied term, if it is "certain, notorious, reasonable, recognised as legally binding and consistent with the express terms".[182]

In specific contracts, such as those for sales of goods, between a landlord and tenant, or in employment, the courts imply standardized contractual terms (or terms "implied in law"). Such terms set out a menu of "default rules" that generally apply in absence of true agreement to the contrary. In one instance of partial codification, the Sale of Goods Act 1893 summed up all the standard contractual provisions in typical commercial sales agreements developed by the common law. This is now updated in the Sale of Goods Act 1979, and in default of people agreeing something different in general its terms will apply. For instance, under section 12–14, any contract for sale of goods carries the implied terms that the seller has legal title, that it will match prior descriptions and that it is of satisfactory quality and fit for purpose. Similarly the Supply of Goods and Services Act 1982 section 13 says services must be performed with reasonable care and skill. As a matter of common law the test is what terms are a "necessary incident" to the specific type of contract in question. This test derives from Liverpool City Council v Irwin[184] where the House of Lords held that, although fulfilled on the facts of the case, a landlord owes a duty to tenants in a block of flats to keep the common parts in reasonable repair. In employment contracts, multiple standardized implied terms arise also, even before statute comes into play, for instance to give employees adequate information to make a judgment about how to take advantage of their pension entitlements.[185] The primary standardized employment term is that both employer and worker owe one another an obligation of "mutual trust and confidence". Mutual trust and confidence can be undermined in multiple ways, primarily where an employer's repulsive conduct means a worker can treat herself as being constructively dismissed.[186] In Mahmud and Malik v Bank of Credit and Commerce International SA[187] the House of Lords held the duty was breached by the employer running the business as a cover for numerous illegal activities. The House of Lords has repeated that the term may always be excluded, but this has been disputed because unlike a contract for goods or services among commercial parties, an employment relation is characterized by unequal bargaining power between employer and worker. In Johnstone v Bloomsbury Health Authority[188] the Court of Appeal all held that a junior doctor could not be made to work at an average of 88 hours a week, even though this was an express term of his contract, where it would damage his health. However, one judge said that result followed from application of the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977, one judge said it was because at common law express terms could be construed in the light of implied terms, and one judge said implied terms may override express terms.[189] Even in employment, or in consumer affairs, English courts remain divided about the extent to which they should depart from the basic paradigm of contractual freedom, that is, in absence of legislation.

Unfair terms

[edit]"None of you nowadays will remember the trouble we had – when I was called to the Bar – with exemption clauses. They were printed in small print on the back of tickets and order forms and invoices. They were contained in catalogues or timetables. They were held to be binding on any person who took them without objection. No one ever did object. He never read them or knew what was in them. No matter how unreasonable they were, he was bound. All this was done in the name of "freedom of contract." But the freedom was all on the side of the big concern which had the use of the printing press. No freedom for the little man who took the ticket or order form or invoice. The big concern said, "Take it or leave it." The little man had no option but to take it.... When the courts said to the big concern, "You must put it in clear words," the big concern had no hesitation in doing so. It knew well that the little man would never read the exemption clauses or understand them. It was a bleak winter for our law of contract."

In the late 20th century, Parliament passed its first comprehensive incursion into the doctrine of contractual freedom in the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977. The topic of unfair terms is vast, and could equally include specific contracts falling under the Consumer Credit Act 1974, the Employment Rights Act 1996 or the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985. Legislation, particularly regarding consumer protection, is also frequently being updated by the European Union, in laws like the Flight Delay Compensation Regulation,[190] or the Electronic Commerce Directive,[191] which are subsequently translated into domestic law through a statutory instrument authorized through the European Communities Act 1972 section 2(2), as for example with the Consumer Protection (Distance Selling) Regulations 2000. The primary legislation on unfair consumer contract terms deriving from the EU is found in the Consumer Rights Act 2015.[192] The Law Commission had drafted a unified Unfair Contract Terms Bill,[193] but Parliament chose to maintain two extensive documents.

The Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 regulates clauses that exclude or limit terms implied by the common law or statute. Its general pattern is that if clauses restrict liability, particularly negligence, of one party, the clause must pass the "reasonableness test" in section 11 and Schedule 2. This looks at the ability of either party to get insurance, their bargaining power and their alternatives for supply, and a term's transparency.[194] In places the Act goes further. Section 2(1) strikes down any term that would limit liability for a person's death or personal injury. Section 2(2) stipulates that any clause restricting liability for loss to property has to pass the "reasonableness test". One of the first cases, George Mitchell Ltd v Finney Lock Seeds Ltd[195] saw a farmer successfully claim that a clause limiting the liability of a cabbage seed seller to damages for replacement seed, rather than the far greater loss of profits after crop failure, was unreasonable. The sellers were in a better position to get insurance for the loss than the buyers. Under section 3 businesses cannot limit their liability for breach of contract if they are dealing with "consumers", defined in section 12 as someone who is not dealing in the course of business with someone who is, or if they are using a written standard form contract, unless the term passes the reasonableness test.[196] Section 6 states the implied terms of the Sale of Goods Act 1979 cannot be limited unless reasonable. If one party is a "consumer" then the SGA 1979 terms become compulsory under the CRA 2015. In other words, a business can never sell a consumer goods that do not work, even if the consumer signed a document with full knowledge of the exclusion clause. Under section 13, it is added that variations on straightforward exemption clauses will still count as exemption clauses caught by the Act. So for example, in Smith v Eric S Bush[197] the House of Lords held that a surveyor's term limiting liability for negligence was ineffective, after the chimney came crashing through Mr Smith's roof. The surveyor could get insurance more easily than Mr Smith. Even though there was no contract between them, because section 1(1)(b) applies to any notice excluding liability for negligence, and even though the surveyor's exclusion clause might prevent a duty of care arising at common law, section 13 "catches" it if liability would exist "but for" the notice excluding liability: then the exclusion is potentially unfair.

Relatively few cases are ever brought directly by consumers, given the complexity of litigation, cost, and its worth if claims are small. In order to ensure consumer protection laws are actually enforced, the Competition and Markets Authority has jurisdiction to bring consumer regulation cases on behalf of consumers after receiving complaints. Under the Consumer Rights Act 2015 section 70 and Schedule 3, the CMA has jurisdiction to collect and consider complaints, and then seek injunctions in the courts to stop businesses using unfair terms (under any legislation). The CRA 2015 is formally broader than UCTA 1977 in that it covers any unfair terms, not just exemption clauses, but narrower in that it only operates for consumer contracts. Under section 2, a consumer is an "individual acting for purposes that are wholly or mainly outside that individual's trade, business, craft or profession."[198] However, while the United Kingdom could always opt for greater protection, when it translated the Directive into national law it opted to follow the bare minimum requirements, and not to cover every contract term. Under section 64, a court may only assess the fairness of terms that do not specify "the main subject matter of the contract", or terms which relate to "appropriateness of the price payable" of the thing sold. Outside such "core" terms, a term may be unfair, under section 62 if it is not one that is individually negotiated, and if contrary to good faith it causes a significant imbalance in the rights and obligations of the parties. A list of examples of unfair terms are set out in Schedule 2. In DGFT v First National Bank plc[199] the House of Lords held that given the purpose of consumer protection, the predecessor to section 64 should be construed tightly and Lord Bingham stated good faith implies fair, open and honest dealing. This all meant that the bank's practice of charging its (higher) default interest rate to customers who had (lower) interest rate set by a court under a debt restructuring plan could be assessed for fairness, but the term did not create such an imbalance given the bank wished only to have its normal interest. This appeared to grant a relatively open role for the Office of Fair Trading to intervene against unfair terms. However, in OFT v Abbey National plc[200] the Supreme Court held that if a term related in any way to price, it could not by virtue of section 64 be assessed for fairness. All the High Street banks, including Abbey National, had a practice of charging high fees if account holders, unplanned, exceeded through withdrawals their normal overdraft limit. Overturning a unanimous Court of Appeal,[201] the Supreme Court viewed that if the thing being charged for was part of a "package" of services, and the bank's remuneration for its services partly came from these fees, then there could be no assessment of the fairness of terms. This controversial stance was tempered by their Lordships' emphasis that any charges must be wholly transparent,[202] though its compatibility with EU law is not yet established by the European Court of Justice, and it appears questionable that it would be decided the same way if inequality of bargaining power had been taken into account, as the Directive requires.[203]

Termination and remedies

[edit]

Although promises are made to be kept, parties to an agreement are generally free to determine how a contract is terminated, can be terminated and remedial consequences for breach of contract, just as they can generally determine a contract's content. The courts have fashioned only residual limits on the parties' autonomy to determine how a contract terminates. The courts' default, or standard rules, which are generally alterable, are first that a contract is automatically concluded if it becomes impossible for one party to perform. Second, if one party breaches her side of the bargain in a serious way, the other party may cease his own performance. If a breach is not serious, the innocent party must continue his own obligations but may claim a remedy in court for the defective or imprecise performance he has received. Third, the principle remedy for breach of contract is compensatory damages, limited to losses that one might reasonably expect to result from a breach. This means a sum of money to put the claimant in mostly the same position as if the contract breaker had performed her obligations. In a small number of contract cases, closely analogous to property or trust obligations, a court may order restitution by the contract breaker so that any gains she has made by breaking the agreement will be stripped and given to the innocent party. Additionally where a contract's substance is for something so unique that damages would be an inadequate remedy courts may use their discretion to grant an injunction against the contract breaker doing something or, unless it is a personal service, positively order specific performance of the contract terms.

Performance and breach

[edit]Generally speaking, all parties to a contract must precisely perform their obligations or there is a breach of contract and, at the least, damages can be claimed. However, as a starting point, to claim that someone else has breached their side of a bargain, one must have at least "substantially performed" their own obligations. For example, in Sumpter v Hedges[204] a builder performed £333 worth of work, but then abandoned completion of the contract. The Court of Appeal held he could not recover any money for the building left on the land, even though the buyer subsequently used the foundations to complete the job.[205] This rule provides a powerful remedy in home construction cases to a customer. So in Bolton v Mahadeva[206] Mr Bolton installed a £560 heating system in Mahadeva's house. However, it leaked and would cost £174 to correct (i.e. 31% of the price). Mahadeva did not pay at all, and the Court of Appeal held this was lawful because the performance was so defective that there could not be said to be any substantial performance. However where an obligation in a contract is "substantially performed", the full sum must be paid, only then deducting an amount to reflect the breach. So in Hoenig v Isaacs[207] Denning LJ held a builder who installed a bookcase poorly, with a price of £750 but costing only £55 to correct (i.e. 7.3% of the price), had to be paid minus the cost of correction.[208] If a contract's obligations are construed as consisting of an "entire obligation", performance of it all will be a condition precedent (a requirement before) to performance from the other side falling due, and allowing a breach of contract claim.

In the simplest case of a contractual breach, the performance that was owed will merely be the payment of a provable debt (an agreed sum of money). In this case, the Sale of Goods Act 1979 section 49 allows for a summary action for price of goods or services, meaning a quick set of court procedure rules are followed. Consumers also benefit under sections 48A-E, with a specific right to have a broken product to be repaired. An added benefit is that if a claimant brings an action for debt, she or he will have no further duty to mitigate his loss. This was another requirement that common law courts had invented, before a claim for breach of contract could be enforced. For instance, in contracts for services that spanned a long period of time (e.g. 5 years), the courts would often state that because a claimant should be able to find alternative work in a few months, and so should not receive money for the whole contract's duration. However, White & Carter (Councils) Ltd v McGregor[209] an advertising company had a contract to display adverts for McGregor's garage business on public dustbins. McGregor said he wished to cancel the deal, but White & Carter Ltd refused, displayed the adverts anyway, and demanded the full sum of money. McGregor argued that they should have attempted to mitigate their loss by finding other clients, but the majority of the Lords held there was no further duty to mitigate. Claims in debt were different from damages.

Remedies are often agreed in a contract, so that if one side fails to perform the contract will dictate what happens. A simple, common and automatic remedy is to have taken a deposit, and to retain it in the event of non-performance. However, the courts will often treat any deposit that exceeds 10 per cent of the contract price as excessive. A special justification will be required before any greater sum may be retained as a deposit.[210] The courts will view a large deposit, even if expressed in crystal clear language, as a part payment of the contract which if unperformed must be restored in order to prevent unjust enrichment. Nevertheless, where commercial parties of equal bargaining power wish to insist on circumstances in which a deposit will be forfeit and insist precisely on the letter of their deal, the courts will not interfere. In Union Eagle Ltd v Golden Achievement Ltd[211] a purchaser of a building in Hong Kong for HK$4.2 million had a contract stipulating completion must take place by 5 pm on 30 September 1991 and that if not a 10 per cent deposit would be forfeited and the contract rescinded. The purchaser was 10 minutes late only, but the Privy Council advised that given the necessity of certain rules and to remove business' fear of courts exercising unpredictable discretion, the agreement would be strictly enforced. Agreements may also state that, as opposed to a sum fixed by the courts, a particular sum of "liquidated damages" will be paid upon non-performance. The courts place an outer-limit on liquidated damages clauses if they became so high, or "extravagant and unconscionable" as to look like a penalty.[212] Penalty clauses in contracts are generally not enforceable. However this jurisdiction is exercised rarely, so in Murray v Leisureplay plc[213] the Court of Appeal held that a severance payment of a whole year's salary to a company's Chief Executive in the event of dismissal before a year was not a penalty clause. The recent decision of Cavendish Square Holding BV v Talal El Makdessi, together with its companion case ParkingEye Ltd v Beavis, decided that the test for whether a clause is unenforceable by virtue of it being a penalty clause is 'whether the impugned provision is a secondary obligation which imposes a detriment on the contract-breaker out of all proportion to any legitimate interest of the innocent party in the enforcement of the primary obligation'. This means that even though a sum is not a genuine pre-estimate of loss, it is not a penalty if it protects a legitimate interest of the claimant in the performance of the contract and is not out of proportion in doing so. In ParkingEye, legitimate interests had included maintaining the good will of the parking company and encouraging a prompt turnover of the car parking spaces. Additionally, the ability of courts to strike down clauses as penalties only applies to clauses for payment of money upon the breach of the contract rather than events during its performance,[214] though the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999[215] confers jurisdiction to interfere with unfair terms used against consumers.

Frustration and common mistake

[edit]

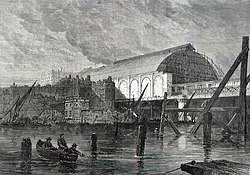

Early common law cases held that performance of a contract always had to take place. No matter what hardship was encountered contracting parties had absolute liability on their obligations.[217] In the 19th century the courts developed a doctrine that contracts which became impossible to perform would be frustrated and automatically come to an end. In Taylor v Caldwell Blackburn J held that when the Surrey Gardens Music Hall unexpectedly burnt down, the owners did not have to pay compensation to the business that had leased it for an extravagant performance, because it was neither party's fault. An assumption underlying all contracts (a "condition precedent") is that they are possible to perform. People would not ordinarily contract to do something they knew was going to be impossible. Apart from physical impossibility, frustration could be down to a contract becoming illegal to perform, for instance if war breaks out and the government bans trade to a belligerent country,[218] or perhaps if the whole purpose of an agreement is destroyed by another event, like renting a room to watch a cancelled coronation parade.[219] But a contract is not frustrated merely because a subsequent event makes the agreement harder to perform than expected, as for instance in Davis Contractors Ltd v Fareham UDC where a builder unfortunately had to spend more time and money doing a job than he would be paid for because of an unforeseen shortage of labour and supplies. The House of Lords denied his claim for contract to be declared frustrated so he could claim quantum meruit.[220] Because the doctrine of frustration is a matter of construction of the contract, it can be contracted around, through what are called "force majeure" clauses.[221] Similarly, a contract can have a force majeure clause that would bring a contract to an end more easily than would common law construction. In The Super Servant Two[222] Wijsmuller BV contracted to hire out a self-propelling barge to J. Lauritzen A/S, who wanted to tow another ship from Japan to Rotterdam, but had a provision stating the contract would terminate if some event made it difficult related to the 'perils or dangers and accidents of the sea'. Wijsmuller BV also had a choice of whether to provide either The Superservant One or Two. They chose Two and it sank. The Court of Appeal held that the impossibility to perform the agreement was down to Wijsmuller's own choice, and so it was not frustrated, but that the force majeure clause did cover it. The effect of a contract being frustrated is that it is that both parties are prospectively discharged from performing their side of the bargain. If one side has already paid money over or conferred another valuable benefit, but not got anything in return yet, contrary to the prior common law position,[223] the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943 gives the court discretion to let the claimant recover a 'just sum',[224] and that means whatever the court thinks fit in all the circumstances.[225]