Estonians

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 16 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 16 min

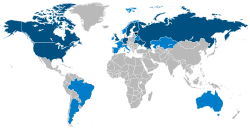

Countries with significant Estonian population and descendants. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 1.1 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

Other significant population centers: | |

| 49,590–100,000[a][3][4] | |

| 29,128[5] | |

| 25,509[6] | |

| 24,000[7] | |

| 10,000–15,000[8] | |

| 7,778[9] | |

| 7,543[10] | |

| 6,286[11] | |

| 5,092[12] | |

| 2,868[13] | |

| 2,560[14] | |

| 2,000[15] | |

| 1,676[16] | |

| 1,658[17] | |

| 1,482[18] | |

| Languages | |

| Primarily Estonian also Võro and Seto | |

| Religion | |

| Majority irreligious Historically Protestant Christian (Lutheranism)[19][20] Currently Lutheran and regional Eastern Orthodox (Estonian Apostolic Orthodox) minority | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Baltic Finns | |

Estonians or Estonian people (Estonian: eestlased) are a Finnic ethnic group native to the Baltic Sea region in Northern Europe, primarily their nation state of Estonia.

Estonians primarily speak the Estonian language, a language closely related to other Finnic languages, e.g. Finnish, Karelian and Livonian. The Finnic languages are a subgroup of the larger Uralic family of languages, which also includes e.g. the Sami languages. These languages are markedly different from most other native languages spoken in Europe, most of which have been assigned to the Indo-European family of languages. Estonians can also be classified into subgroups according to dialects (e.g. Võros, Setos), although such divisions have become less pronounced due to internal migration and rapid urbanisation in Estonia in the 20th century.

There are approximately 1 million ethnic Estonians worldwide, with the vast majority of them residing in their native Estonia. Estonian diaspora communities formed primarily in Finland, the United States, Sweden, Canada, and the United Kingdom.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Prehistoric roots

[edit]Estonia was first inhabited about 13,000–11,000 years ago, when the Baltic Ice Lake melted. Living in the same area for more than 5,000 years would put Estonians' ancestors among Europe's oldest permanent inhabitants.[21] On the other hand, some recent linguistic estimations suggest that Finno-Ugric speakers arrived around the Baltic Sea considerably later, perhaps during the Early Bronze Age (ca. 1800 BCE).[22][23] It has also been argued that Western Uralic tribes reached Fennoscandia first, leading into the development of the Sámi peoples, and arrived in the Baltic region later in the Bronze Age[24] or the transition to the Iron Age at the latest.[25] This lead into the formation of Baltic Finnic peoples, who would later become such groups as Estonians and Finns.[24]

The oldest known endonym of the Estonians is maarahvas,[26] literally meaning "land people" or "country folk". It was used until the mid-19th century, when it was gradually replaced by Eesti rahvas "Estonian people" during the Estonian national awakening.[27][28] Eesti, the modern endonym of Estonia, is thought to have similar origins to Aesti, the name used by the Germanic peoples for the neighbouring people living northeast of the mouth of the Vistula. The Roman historian Tacitus in 98 CE was the first to mention the "Aesti" in writing. In Old Norse, the land south of the Gulf of Finland was called Eistland and the people eistr. The Wanradt–Koell Catechism, the first known book in Estonian, was printed in 1525, while the oldest known examples of written Estonian originate in 13th-century chronicles.

National consciousness

[edit]

Although Estonian national consciousness spread in the course of the 19th century during the Estonian national awakening,[29] some degree of ethnic awareness preceded this development.[30] By the 18th century the self-denomination eestlane spread among Estonians along with the older maarahvas.[26] Anton thor Helle's translation of the Bible into Estonian appeared in 1739, and the number of books and brochures published in Estonian increased from 18 in the 1750s to 54 in the 1790s. By 1800, more than a half of adult Estonians could read. The first university-educated intellectuals identifying themselves as Estonians, including Friedrich Robert Faehlmann (1798–1850), Kristjan Jaak Peterson (1801–1822) and Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald (1803–1882), appeared in the 1820s. The ruling elites had remained predominantly German in language and culture since the conquest of the early 13th century. Garlieb Merkel (1769–1850), a Baltic-German Estophile, became the first author to treat the Estonians as a nationality equal to others; he became a source of inspiration for the Estonian national movement, modelled on Baltic German cultural world before the middle of the 19th century. However, in the middle of the century, Estonians became more ambitious and started leaning toward the Finns and their so-called Fennoman movement as successful model of national movement. By the end of 1860s, the Estonians became unwilling to reconcile with German cultural and political hegemony. Before the attempts at Russification in the 1880s, their view of the Russian Empire remained positive.[30]

Estonians have strong ties to the Nordic countries stemming from important cultural and religious influences gained over centuries during Scandinavian and German rule and settlement.[31] According to a poll done in 2013, about half of the young Estonians considered themselves Nordic, and about the same number viewed Baltic identity as important. The Nordic identity among Estonians can ovelap with other identities, as it is associated with being Finno-Ugric and their close relationship with the Finnish people and does not exclude being Baltic.[32] In Estonian foreign ministry reports from the early 2000s Nordic identity was preferred over Baltic one.[33][34]

After the Treaty of Tartu (1920) recognised Estonia's 1918 independence from Russia, ethnic Estonians residing in Russia gained the option to acquire the citizenship of Estonia upon returning to the newly independent country. An estimated 40,000 Estonians lived in Russia in 1920, and 37,578 people resettled from Russia to Estonia in 1920–1923.[citation needed]

Emigration

[edit]During World War II, when Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Army in 1944, large numbers of Estonians fled their homeland on ships or smaller boats over the Baltic Sea. Many refugees who survived the risky sea voyage to Sweden or Germany later moved from there to Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States or Australia.[35] Some of these refugees and their descendants returned to Estonia after the nation regained its independence in 1991.

Over the years of independence, many Estonians have chosen to work abroad, primarily in Finland, but also in the UK, Benelux, Sweden, and Germany.[36]

Estonians in Canada

[edit]One of the largest permanent Estonian communities outside Estonia is in Canada, with about 24,000 people[7] (according to some sources up to 50,000 people).[37] In the late 1940s and early 1950s, about 17,000 arrived in Canada, initially in Montreal.[38] Toronto is currently the city with the largest population of Estonians outside of Estonia. The first Estonian World Festival was held in Toronto in 1972.

Genetics

[edit]Uniparental haplogroups

[edit]Y-chromosome haplogroups among Estonians include N1c (35.7%),[39] R1a (33.5%)[40] and I1 (15%).[39] R1a, common in Eastern Europe,[41] was the dominant Y-DNA haplogroup among the pre-Uralic inhabitants of Estonia, as it is the only one found in the local samples from the time of the Corded Ware culture and Bronze Age. Appearance of N1c is linked to the arrival of Uralic-speakers.[25] It originated in East Eurasia[42] and is commonly carried by modern Uralic-speaking groups but also other North Eurasians, including Estonians' Baltic-speaking neighbors Latvians and Lithuanians.[39] Compared to the Balts, Estonians have been noticed to have differences in allelic variances of N1c haplotypes, showing more similarity with other Finno-Ugric-speakers.[43][41]

When looking at maternal lineages, nearly half (45 %) of the Estonians have the haplogroup H . About one in four (24.2 %) carry the haplogroup U, and the majority of them belong to its subclade U5.[42]

Autosomal DNA

[edit]

Autosomally Estonians are close with Latvians and Lithuanians[46] However, they are shifted towards the Finns, who are isolated from most European populations.[47][48][49] Northeastern Estonians are particularly close to Finns, while southeastern Estonians are close to the Balts; other Estonians plot between these two extremes.[45]

Estonians have high steppe-like admixture, and less farmer-related and more hunter-gatherer-related admixture than Western and Central Europeans. The same pattern is found also in the Balts, Finns and Mordvins, for example.[50] Uralic peoples typically carry a Siberian-related component, which is also present in Estonians and makes up about five percent of their ancestry on average. Although they have a smaller share of it than other Finnic-speakers, it is one factor that distinguishes them from the Balts.[42] Estonians can also be modelled to have considerably more Finnish-like ancestry than Baltic-speakers.[49][43]

Estonians have a high sharing of IBD (identity-by-descent) segments with other studied Finnic groups (Finns, Karelians and Vepsians) and the Sami people, as well as with the Polish people.[46]

See also

[edit]- Demographics of Estonia

- Estonian Americans

- Estonian Argentines

- Estonian Australians

- Estonian Canadians

- Estonian national awakening

- Gauja Estonians

- List of Estonian Americans

- List of notable Estonians

Notes

[edit]- ^ Statistics Finland does not record ethnicity and instead categorizes the population by their native language; in 2017, Estonian was spoken as a mother tongue by 49,590 people, not all of whom may be ethnic Estonians.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Estai

- ^ "Population by ethnic nationality". Statistics Estonia. June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Population". Statistics Finland. 4 April 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Up to 100 000 Estonians work in Finland". Baltic News Network. 27 December 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Table B04006 - People Reporting Ancestry - 2021 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 17 September 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ "Eestlased Rootsis". Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Canada-Estonia Relations". Archived from the original on 20 November 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "United Kingdom". Ethnologue. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "Национальный состав населения". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "2054.0 Australian Census Analytic Program: Australians' Ancestries (2001 (Corrigendum))" (PDF). Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2001. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ "Pressemitteilungen – Ausländische Bevölkerung – Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis)". www.destatis.de.

- ^ "Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents, 1 January 2016". Statistics Norway. Accessed 01 May 2016.

- ^ "The distribution of the population by nationality and mother tongue". State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. 2001. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008.

- ^ "Persons usually resident and present in the State on Census Night, classified by place of birth and age group". Central Statistics Office Ireland. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Estemb in Belgium and Luxembourg". Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "Usually resident population by ethnicity at the beginning of the year – 2018". csb.gov.lv.

- ^ "Statistikbanken". www.statistikbanken.dk. Population at the first day of the quarter by country of origin, region and time. Retrieved on 23 May 2024.

- ^ Official CBS website containing all Dutch demographic statistics. Cbs.nl. Retrieved on 4 July 2017.

- ^ Ivković, Sanja Kutnjak; Haberfeld, M.R. (10 June 2015). Measuring Police Integrity Across the World: Studies from Established Democracies and Countries in Transition. Springer. p. 131. ISBN 9781493922796.

Estonia is considered Protestant when classified by its historically predominant major religion (Norris and Inglehart 2011) and thus some authors (e.g., Davie 2003) claim Estonia belongs to Western (Lutheran) Europe, while others (e.g., Norris and Inglehart 2011) see Estonia as a Protestant ex-Communist society.

- ^ Ringvee, Ringo (16 September 2011). "Is Estonia really the least religious country in the world?". The Guardian.

For this situation there are several reasons, starting from the distant past (the close connection of the churches with the Swedish or German ruling classes) up to the Soviet-period atheist policy when the chain of religious traditions was broken in most families. In Estonia, religion has never played an important role on the political or ideological battlefield. The institutional religious life was dominated by foreigners until the early 20th century. The tendencies that prevailed in the late 1930s for closer relations between the state and Lutheran church [...] ended with the Soviet occupation in 1940.

- ^ Unrepresented Nations and peoples organization By Mary Kate Simmons; p141 ISBN 978-90-411-0223-2

- ^ Petri Kallio 2006: Suomalais-ugrilaisen kantakielen absoluuttisesta kronologiasta. — Virittäjä 2006. (With English summary).

- ^ Häkkinen, Jaakko (2009). "Kantauralin ajoitus ja paikannus: perustelut puntarissa. – Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Aikakauskirja" (PDF). p. 92.

- ^ a b Lang, Valter: Homo Fennicus – Itämerensuomalaisten etnohistoria, pp. 335–336. Finnish Literature Society, 2020. ISBN 978-951-858-130-0

- ^ a b Saag, Lehti; Laneman, Margot; Varul, Liivi; Malve, Martin; Valk, Heiki; Razzak, Maria A.; Shirobokov, Ivan G.; Khartanovich, Valeri I.; Mikhaylova, Elena R.; Kushniarevich, Alena; Scheib, Christiana Lyn; Solnik, Anu; Reisberg, Tuuli; Parik, Jüri; Saag, Lauri; Metspalu, Ene; Rootsi, Siiri; Montinaro, Francesco; Remm, Maido; Mägi, Reedik; D’Atanasio, Eugenia; Crema, Enrico Ryunosuke; Díez-del-Molino, David; Thomas, Mark G.; Kriiska, Aivar; Kivisild, Toomas; Villems, Richard; Lang, Valter; Metspalu, Mait; Tambets, Kristiina (May 2019). "The Arrival of Siberian Ancestry Connecting the Eastern Baltic to Uralic Speakers further East". Current Biology. 29 (10): 1701–1711.e16. Bibcode:2019CBio...29E1701S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.026. PMC 6544527. PMID 31080083.

- ^ a b Ariste, Paul (1956). "Maakeel ja eesti keel. Eesti NSV Teaduste Akadeemia Toimetised 5: 117–24; Beyer, Jürgen (2007). Ist maarahvas ('Landvolk'), die alte Selbstbezeichnung der Esten, eine Lehnübersetzung? Eine Studie zur Begriffsgeschichte des Ostseeraums". Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung. 56: 566–593.

- ^ Beyer, Jürgen (April 2011). "Are Folklorists Studying the Tales of the Folk?". Folklore. 122 (1): 35–54. doi:10.1080/0015587X.2011.537132. S2CID 144633422.

- ^ Paatsi, Vello (2012). ""Terre, armas eesti rahwas!": Kuidas maarahvast ja maakeelest sai eesti rahvas, eestlased ja eesti keel". Akadeemia (in Estonian). 24 (2): 20–21. ISSN 0235-7771. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ Gellner, Ernest (1996). "Do nations have navels?". Nations and Nationalism. 2 (3): 365–70. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8219.1996.tb00003.x.

- ^ a b Raun, Toivo U (2003). "Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Estonian nationalism revisited". Nations and Nationalism. 9 (1): 129–147. doi:10.1111/1469-8219.00078.

- ^ Piirimäe, Helmut. Historical heritage: the relations between Estonia and her Nordic neighbors. In M. Lauristin et al. (eds.), Return to the Western world: Cultural and political perspectives on the Estonian post-communist transition. Tartu: Tartu University Press, 1997.

- ^ "How Nordic is Estonia?: An overview since 1991". nordics.info. 28 December 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ Estonian foreign ministry report Archived 25 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, 2004

- ^ Estonian foreign ministry report Archived 7 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 2002

- ^ Past, Evald, By Land and By Sea, Booklocker, 2015, ISBN 978-0-9867510-0-4

- ^ "The CIA World Factbook Country Comparison of net migration rate". cia.gov. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Estonian Embassy in Ottawa". Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "The Estonian Presence in Toronto". Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ a b c Lang, Valter: Homo Fennicus – Itämerensuomalaisten etnohistoria, pp. 93–95. Finnish Literature Society, 2020. ISBN 978-951-858-130-0.

- ^ Tambets, Kristiina; Rootsi, Siiri; Kivisild, Toomas; Help, Hela; Serk, Piia; Loogväli, Eva-Liis; Tolk, Helle-Viivi; Reidla, Maere; Metspalu, Ene; Pliss, Liana; Balanovsky, Oleg; Pshenichnov, Andrey; Balanovska, Elena; Gubina, Marina; Zhadanov, Sergey (2004). "The Western and Eastern Roots of the Saami—the Story of Genetic "Outliers" Told by Mitochondrial DNA and Y Chromosomes". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (4): 661–682. doi:10.1086/383203. PMC 1181943. PMID 15024688.

- ^ a b Lappalainen, Tuuli: Human genetic variation in the Baltic Sea region: features of population history and natural selection. PhD thesis. Helsinki University Print, Helsinki. 2009. http://hdl.handle.net/10138/22129

- ^ a b c Tambets, Kristiina; Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Hudjashov, Georgi; Ilumäe, Anne-Mai; Rootsi, Siiri; Honkola, Terhi; Vesakoski, Outi; Atkinson, Quentin; Skoglund, Pontus; Kushniarevich, Alena; Litvinov, Sergey; Reidla, Maere; Metspalu, Ene; Saag, Lehti; Rantanen, Timo (2018). "Genes reveal traces of common recent demographic history for most of the Uralic-speaking populations". Genome Biology. 19 (1): 139. doi:10.1186/s13059-018-1522-1. ISSN 1474-760X. PMC 6151024. PMID 30241495.

- ^ a b Krūmiņa, Astrīda; Pliss, Liāna; Zariņa, Gunita; Puzuka, Agrita; Zariņa, Agnese; Lāce, Baiba; Elferts, Didzis; Khrunin, Andrey; Limborska, Svetlana; Kloviņš, Jānis; Gailīte Piekuse, Linda (1 June 2018). "Population Genetics of Latvians in the Context of Admixture between North-Eastern European Ethnic Groups". Proceedings of the Latvian Academy of Sciences. Section B. Natural, Exact, and Applied Sciences. 72 (3): 131–151. doi:10.2478/prolas-2018-0025. ISSN 1407-009X.

- ^ Stamatoyannopoulos, George; Bose, Aritra; Teodosiadis, Athanasios; Tsetsos, Fotis; Plantinga, Anna; Psatha, Nikoletta; Zogas, Nikos; Yannaki, Evangelia; Zalloua, Pierre; Kidd, Kenneth K.; Browning, Brian L.; Stamatoyannopoulos, John; Paschou, Peristera; Drineas, Petros (2017). "Genetics of the peloponnesean populations and the theory of extinction of the medieval peloponnesean Greeks". European Journal of Human Genetics. 25 (5): 637–645. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2017.18. ISSN 1476-5438. PMC 5437898. PMID 28272534.

- ^ a b Pankratov, Vasili; Montinaro, Francesco; Kushniarevich, Alena; Hudjashov, Georgi; Jay, Flora; Saag, Lauri; Flores, Rodrigo; Marnetto, Davide; Seppel, Marten; Kals, Mart; Võsa, Urmo; Taccioli, Cristian; Möls, Märt; Milani, Lili; Aasa, Anto (2020). "Differences in local population history at the finest level: the case of the Estonian population". European Journal of Human Genetics. 28 (11): 1580–1591. doi:10.1038/s41431-020-0699-4. ISSN 1476-5438. PMC 7575549. PMID 32712624.

- ^ a b Tambets, Kristiina; Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Hudjashov, Georgi; Ilumäe, Anne-Mai; Rootsi, Siiri; Honkola, Terhi; Vesakoski, Outi; Atkinson, Quentin; Skoglund, Pontus; Kushniarevich, Alena; Litvinov, Sergey; Reidla, Maere; Metspalu, Ene; Saag, Lehti; Rantanen, Timo (2018). "Genes reveal traces of common recent demographic history for most of the Uralic-speaking populations". Genome Biology. 19 (1): 139. doi:10.1186/s13059-018-1522-1. ISSN 1474-760X. PMC 6151024. PMID 30241495.

- ^ Nelis, Mari; Esko, Tõnu; Mägi, Reedik; Zimprich, Fritz; Zimprich, Alexander; Toncheva, Draga; Karachanak, Sena; Piskáčková, Tereza; Balaščák, Ivan; Peltonen, Leena; Jakkula, Eveliina; Rehnström, Karola; Lathrop, Mark; Heath, Simon; Galan, Pilar (8 May 2009). "Genetic Structure of Europeans: A View from the North–East". PLOS ONE. 4 (5): e5472. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.5472N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005472. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2675054. PMID 19424496.

- ^ Kushniarevich, Alena; Utevska, Olga; Chuhryaeva, Marina; Agdzhoyan, Anastasia; Dibirova, Khadizhat; Uktveryte, Ingrida; Möls, Märt; Mulahasanovic, Lejla; Pshenichnov, Andrey; Frolova, Svetlana; Shanko, Andrey; Metspalu, Ene; Reidla, Maere; Tambets, Kristiina; Tamm, Erika (2 September 2015). Calafell, Francesc (ed.). "Genetic Heritage of the Balto-Slavic Speaking Populations: A Synthesis of Autosomal, Mitochondrial and Y-Chromosomal Data". PLOS ONE. 10 (9): e0135820. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035820K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135820. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4558026. PMID 26332464.

- ^ a b Khrunin, Andrey V.; Khokhrin, Denis V.; Filippova, Irina N.; Esko, Tõnu; Nelis, Mari; Bebyakova, Natalia A.; Bolotova, Natalia L.; Klovins, Janis; Nikitina-Zake, Liene; Rehnström, Karola; Ripatti, Samuli; Schreiber, Stefan; Franke, Andre; Macek, Milan; Krulišová, Veronika (7 March 2013). "A Genome-Wide Analysis of Populations from European Russia Reveals a New Pole of Genetic Diversity in Northern Europe". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e58552. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...858552K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058552. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3591355. PMID 23505534.

- ^ Salmela, Elina (2023). "Mistä suomalaisten perimä on peräisin?". Duodecim. 139 (16): 1247–1255. ISSN 0012-7183.

Further reading

[edit]- Petersoo, Pille (January 2007). "Reconsidering otherness: constructing Estonian identity". Nations and Nationalism. 13 (1): 117–133. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8129.2007.00276.x.

External links

[edit]- Office of the Minister for Population and Ethnic Affairs: Estonians abroad

- From Estonia to Thirlmere (online exhibition)

- Our New Home Meie Uus Kodu: Estonian-Australian Stories (online exhibition)

KSF

KSF