Euromaidan

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 79 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 79 min

| Euromaidan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Clockwise from top left: A large European flag is waved across Maidan on 27 November 2013; opposition activist and popular singer Ruslana addresses the crowds on Maidan on 29 November 2013; Euromaidan on European Square on 1 December; plinth of the toppled Lenin statue; crowds direct hose at militsiya; tree decorated with flags and posters. | ||||

| Date | 21 November 2013 – 22 February 2014 (3 months and 1 day) | |||

| Location | Ukraine, primarily Maidan Nezalezhnosti in Kyiv | |||

| Caused by | Main catalyst:

Other factors:

| |||

| Goals |

| |||

| Methods | Demonstrations, civil disobedience, civil resistance, hacktivism,[11] occupation of administrative buildings[nb 1] | |||

| Resulted in | Full results

| |||

| Parties | ||||

| ||||

| Lead figures | ||||

| Number | ||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||

| History of Ukraine |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Political revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

Euromaidan (/ˌjʊərəmaɪˈdɑːn, ˌjʊəroʊ-/ YOOR-oh-my-DAHN;[82][83] Ukrainian: Євромайдан, romanized: Yevromaidan, IPA: [ˌjɛu̯romɐjˈdɑn], lit. 'Euro Square'),[nb 6] or the Maidan Uprising,[87] was a wave of demonstrations and civil unrest in Ukraine, which began on 21 November 2013 with large protests in Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) in Kyiv. The protests were sparked by President Viktor Yanukovych's sudden decision not to sign the European Union–Ukraine Association Agreement, instead choosing closer ties to Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union. Ukraine's parliament had overwhelmingly approved of finalizing the Agreement with the EU,[88] but Russia had put pressure on Ukraine to reject it.[89] The scope of the protests widened, with calls for the resignation of Yanukovych and the Azarov government.[90] Protesters opposed what they saw as widespread government corruption, abuse of power, human rights violations,[91] and the influence of oligarchs.[92] Transparency International named Yanukovych as the top example of corruption in the world.[93] The violent dispersal of protesters on 30 November caused further anger.[5] Euromaidan was the largest democratic mass movement in Europe since 1989[94] and led to the 2014 Revolution of Dignity.

During the uprising, Independence Square (Maidan) in Kyiv was a huge protest camp occupied by thousands of protesters and protected by makeshift barricades. It had kitchens, first aid posts and broadcasting facilities, as well as stages for speeches, lectures, debates and performances.[95][96] It was guarded by 'Maidan Self-Defense' units made up of volunteers in improvised uniform and helmets, carrying shields and armed with sticks, stones and petrol bombs. Protests were also held in many other parts of Ukraine. In Kyiv, there were clashes with police on 1 December; and police assaulted the camp on 11 December. Protests increased from mid-January, in response to the government introducing draconian anti-protest laws. There were deadly clashes on Hrushevsky Street on 19–22 January. Protesters then occupied government buildings in many regions of Ukraine. The uprising climaxed on 18–20 February, when fierce fighting in Kyiv between Maidan activists and police resulted in the deaths of almost 100 protesters and 13 police.[71]

As a result, Yanukovych and the parliamentary opposition signed an agreement on 21 February to bring about an interim unity government, constitutional reforms and early elections. Police abandoned central Kyiv that afternoon, then Yanukovych and other government ministers fled the city that evening.[97] The next day, parliament removed Yanukovych from office[98] and installed an interim government.[99] The Revolution of Dignity was soon followed by the Russian annexation of Crimea and pro-Russian unrest in Eastern Ukraine, eventually escalating into the Russo-Ukrainian War.

Overview

[edit]

The demonstrations began on the night of 21 November 2013, when protests erupted in the capital Kyiv. The protests were launched following the Ukrainian government's suspension of preparations for signing the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement in favour of closer economic relations with Russia and rejection of draft laws which would have allowed the release of jailed opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko.[100] The shift away from the European Union (EU) was preceded by a campaign of threats, insults and preemptive trade restrictions from Russia.[101][102][103][104]

After a few days of demonstrations, an increasing number of university students joined the protests.[105] The Euromaidan has been characterised as an event of major political symbolism for the European Union itself, particularly as "the largest ever pro-European rally in history."[106]

The protests continued despite heavy police presence,[107][108] regular sub-freezing temperatures, and snow. Escalating violence from government forces in the early morning of 30 November caused the level of protests to rise, with 400,000–800,000 protesters demonstrating in Kyiv on the weekends of 1 and 8 December, according to Russia's opposition politician Boris Nemtsov.[109][60] In the preceding weeks, protest attendance had fluctuated from 50,000 to 200,000 during organised rallies.[110][111] Violent riots took place on 1 December and from 19 January through 25 January in response to police brutality and government repression.[112] Starting 23 January, several Western Ukrainian oblast (province) government buildings and regional councils were occupied in a revolt by Euromaidan activists.[16] In the Russophone cities of Zaporizhzhia, Sumy, and Dnipropetrovsk, protesters also tried to take over their local government buildings and were met with considerable resistance from both police and government supporters.[16]

According to journalist Lecia Bushak, writing in the 18 February 2014 issue of Newsweek magazine,

EuroMaidan [had] grown into something far bigger than just an angry response to the fallen-through EU deal. It's now about ousting Yanukovych and his corrupt government; guiding Ukraine away from its 200-year-long, deeply intertwined and painful relationship with Russia; and standing up for basic human rights to protest, speak and think freely and to act peacefully without the threat of punishment.[113]

Late February marked a turning point when many members of the president's party fled or defected, causing it to lose its majority in the Verkhovna Rada, the country's national parliament. A sufficient number of opposition members remained to form the necessary quorum, allowing parliament to pass a series of laws that removed police from Kyiv, canceled anti-protest operations, restored the 2004 constitution, freed political detainees, and removed President Yanukovych from office. Yanukovych then fled to Ukraine's second-largest city of Kharkiv, refusing to recognise the parliament's decisions. The parliament assigned early elections for May 2014.[114]

In early 2019, a Ukrainian court found Yanukovych guilty of treason. Yanukovych was also charged with asking Vladimir Putin to send Russian troops to invade Ukraine after he had fled the country. The charges have had little practical effect on Yanukovych, who has lived in exile in the Russian city of Rostov since fleeing Ukraine under armed guard in 2014.[115]

Background

[edit]Name history

[edit]The term "Euromaidan" was initially used as a hashtag on Twitter after a Twitter account named Euromaidan was created on the first day of the protests.[84][116] The title soon became popular across international media.[117]

The name is composed of two parts: "Euro", which is short for Europe, reflecting the pro-European aspirations of the protestors, and "maidan", referring to Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), a large square in downtown Kyiv where the protests mostly took place. The word "Maidan" is a Persian word meaning "square" or "open space". It is a loanword in many other languages and was adopted into the Ukrainian language during the period of Ottoman Empire influence on Ukraine.[118] During the protests, the word "Maidan" acquired the meaning of the public practice of politics and protest.[119]

When Euromaidan first began, media outlets in Ukraine dubbed the movement Eurorevolution[120] (Ukrainian: Єврореволюція, Russian: Еврореволюция).[121][122] The term "Ukrainian Spring" was also occasionally used during the protests, echoing the term Arab Spring.[123][124]

Initial causes

[edit]On 30 March 2012, the European Union (EU) and Ukraine initiated an Association Agreement;[125] however, EU leaders later stated that the agreement would not be ratified unless Ukraine addressed concerns over a "stark deterioration of democracy and the rule of law", including the imprisonment of Yulia Tymoshenko and Yuriy Lutsenko in 2011 and 2012.[126][nb 7] In the months leading up to the protests, Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych urged the parliament to adopt laws so that Ukraine would meet the EU's criteria.[128][129] On 25 September 2013, Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada Volodymyr Rybak expressed confidence that parliament would pass all the laws needed to fulfill the EU's criteria since, except for the Communist Party of Ukraine, "[t]he Verkhovna Rada has united around these bills."[130] According to Pavlo Klimkin, one of the Ukrainian negotiators of the Association Agreement, initially "the Russians simply did not believe [the association agreement with the EU] could come true. They didn't believe in our ability to negotiate a good agreement and didn't believe in our commitment to implement a good agreement."[131]

In mid-August 2013, Russia changed its customs regulations on imports from Ukraine[132] such that on 14 August 2013, the Russian Customs Service stopped all goods coming from Ukraine[133] and prompted politicians[134] and media[135][136][137] to view the move as the start of a trade war against Ukraine to prevent the country from signing the Association Agreement with the EU. Ukrainian Industrial Policy Minister Mykhailo Korolenko reported on 18 December 2013 that the new Russian trade restrictions had caused Ukraine's exports to drop by $1.4 billion (or a 10% year-on-year decrease through the first 10 months of the year).[132] In November 2013, the State Statistics Service of Ukraine recorded that in comparison with the same months of 2012, in 2013 industrial production in Ukraine had fallen by 4.9% in October, 5.6% in September, and 5.4% in August, with an year-total loss of 1.8% industrial output compared to 2012 levels.[138]

On 21 November 2013, the Ukrainian government decree suspended preparations for the signing of the Association Agreement.[139][140][141] The reason given was that in the previous months, Ukraine had experienced "a drop in industrial production and our relations with CIS [Commonwealth of Independent States] countries".[142][nb 8] The government also assured, "Ukraine will resume preparing the agreement when the drop in industrial production and our relations with Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries are compensated by the European market."[142] According to Prime Minister Mykola Azarov, "the extremely harsh conditions" of an International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan (presented by the IMF on 20 November 2013), which included big budget cuts and a 40% increase in gas bills, had been the last argument in favour of the government's decision to suspend preparations for signing the Association Agreement.[144][145] On 7 December 2013, the IMF clarified that it was not insisting on a single-stage increase in natural gas tariffs in Ukraine by 40%, but recommended that they be gradually raised to an economically justified level while compensating the poorest segments of the population for the losses from the increase by strengthening targeted social assistance.[146] The same day, IMF Resident Representative in Ukraine Jerome Vacher stated that this particular IMF loan was worth US$4 billion and that it would be linked with "policy, which would remove disproportions and stimulate growth".[147][nb 9]

President Yanukovych attended the 28–29 November 2013 EU summit in Vilnius, where the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement was originally planned to be finalised but the agreement was not signed.[128][149][150] Both Yanukovych and high level EU officials signalled that they wanted to sign the Association Agreement at a later date.[151][152][153] Yanukovych later explained to his entourage the decision was the result of an exchange with Russian President Vladimir Putin, who had allegedly threatened to occupy Crimea and a sizable part of southeastern Ukraine, including the Donbas, if he signed the EU agreement.[154]

In an interview with American journalist Lally Weymouth for The Washington Post, Ukrainian billionaire businessman and opposition leader Petro Poroshenko stated:

From the beginning, I was one of the organizers of the Maidan. My television channel—Channel 5—played a tremendously important role. We gave the opportunity to the journalists to tell the truth.... On the 11th of December, when we had [U.S. Assistant Secretary of State] Victoria Nuland and [E.U. diplomat] Catherine Ashton in Kyiv, during the night they started to storm the Maidan. I put my car in front of the riot police.[155]

On 11 December 2013, Prime Minister Mykola Azarov announced that he had asked for €20 billion (US$27 billion) in loans and financial aid to offset the cost of the EU deal.[156] The EU was willing to offer €610 million (US$838 million) in loans with the condition of major reforms to Ukrainian laws and regulations while Russia was willing to offer US$15 billion in loans and cheaper gas prices with no legal reform preconditions.[157][156]

Demands

[edit]

On 29 November, a formal resolution by protest organisers declared three demands:[107]

- The formation of a coordinating committee to communicate with the European community.

- A statement indicating that the president, parliament, and the Cabinet of Ministers weren't capable of carrying out a geopolitically strategic course of development for the state and demanding Yanukovych's resignation.

- The cessation of political repression against EuroMaidan activists, students, civic activists and opposition leaders.

The resolution stated that on 1 December, on the 22nd anniversary of Ukraine's independence referendum, the group would gather at noon on Independence Square (Maidan Nezalezhnosti) to announce their further course of action.[107]

After the forced police dispersal of all protesters from Maidan Nezalezhnosti on the night of 30 November, the dismissal of Minister of Internal Affairs Vitaliy Zakharchenko became one of the protesters' main demands.[158] Ukrainian students nationwide also demanded the dismissal of Minister of Education Dmytro Tabachnyk after a draft law potentially increasing tuition fees was proposed.[159] A petition to the United States' White House demanding sanctions against Viktor Yanukovych and Ukrainian government ministers gathered over 100,000 signatures in four days.[160][161][162]

On 5 December, Batkivshchyna faction leader Arseniy Yatsenyuk stated,

Our three demands to the Verkhovna Rada and the president remained unchanged: the resignation of the government; the release of all political prisoners, first and foremost; [the release of former Ukrainian Prime Minister] Yulia Tymoshenko; and [the release of] nine individuals [who were illegally convicted after being present at a rally on Bankova Street on December 1]; the suspension of all criminal cases; and the arrest of all Berkut officers who were involved in the illegal beating up of children on Maidan Nezalezhnosti.[163]

The opposition also demanded that the government resume negotiations with the IMF for a loan that they saw as key to helping Ukraine "through economic troubles that have made Yanukovych lean toward Russia".[164]

Timeline of the events

[edit]The Euromaidan protest movement began late at night on 21 November 2013 as a peaceful protest.[165] The 1,500 protesters were summoned following a Facebook post by a journalist, Mustafa Nayyem, calling for a rally against the government.[166][167]

Protests in Kyiv

[edit]On 30 November 2013, protests were dispersed violently by Berkut riot police units.[168] On 1 December, more than half a million Kyivans joined the protests in order to defend the students "and to protect society in the face of crippling authoritarianism",[169] and through December, further clashes with the authorities and political ultimatums by the opposition ensued. This culminated in a series of anti-protest laws by the government on 16 January 2014 and further rioting on Hrushevskoho Street. Early February 2014 saw a bombing of the Trade Unions Building,[170] as well as the formation of "Self Defense" teams by protesters.[171]

1 December 2013 protests

[edit]11 December 2013 assault on Maidan

[edit]Hrushevsky Street protests

[edit]On 19 January, up to 200,000 protesters gathered in central Kyiv to oppose the new anti-protest laws, dubbed the Dictatorship Laws.[172][173] Many protesters ignored the face concealment ban by wearing party masks, hard hats and gas masks.[174] They attempted to march from the Maidan to the parliament buildings. Fierce clashes broke out on Hrushevsky Street when the protest march was blocked by riot police. The violent standoff continued for three days, during which three protesters were shot dead by riot police.[71]

February 2014: Revolution

[edit]The deadliest clashes were on 18–20 February, which saw the most severe violence in Ukraine since it regained independence.[175] Thousands of protesters advanced towards parliament, led by activists with shields and helmets, and were fired on by the Berkut and police snipers. Almost 100 were killed.[71][176]

On 21 February, an agreement was signed by Yanukovych and leaders of the parliamentary opposition (Vitaly Klitschko, Arseny Yatsenyuk, Oleh Tyahnybok) under the mediation of EU and Russian representatives. There was to be an interim unity government formed, constitutional reforms to reduce the president's powers, and early elections.[92] Protesters were to leave occupied buildings and squares, and the government would not apply a state of emergency.[92] The United States supported a stipulation that Yanukovych remain president in the meantime, but Maidan protesters demanded his resignation.[92] The signing was witnessed by Foreign Ministers of Poland, Germany and France.[177] The Russian representative would not sign the agreement.[92]

The next day, 22 February, Yanukovych fled to Donetsk and Crimea and parliament voted to remove him from office.[178][179][180] On 24 February Yanukovych arrived in Russia.[181]

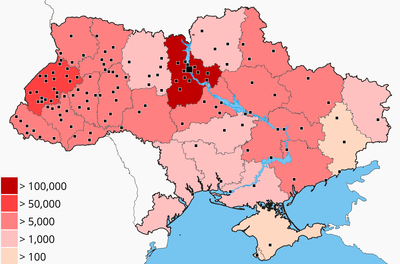

Protests across Ukraine

[edit]| City | Peak attendees | Date | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kyiv | 400,000–800,000 | 1 Dec | [60] |

| Lviv | 50,000 | 1 Dec | [63] |

| Kharkiv | 30,000 | 22 Feb | [182] |

| Cherkasy | 20,000 | 23 Jan | [64] |

| Ternopil | 20,000+ | 8 Dec | [183] |

| Dnipropetrovsk (now Dnipro) | 15,000 | 2 Mar | [107][184] |

| Ivano-Frankivsk | 10,000+ | 8 Dec | [185] |

| Lutsk | 8,000 | 1 Dec | [186] |

| Sumy | 10,000 | 2 Mar | [187] |

| Poltava | 10,000 | 24 Jan | [188] |

| Donetsk | 10,000 | 5 Mar | [189] |

| Zaporizhzhia | 10,000 | 26 Jan | [190] |

| Chernivtsi | 4,000–5,000 | 1 Dec | [186] |

| Simferopol | 5,000+ | 23 Feb | [191] |

| Rivne | 4,000–8,000 | 2 Dec | [192] |

| Mykolaiv | 10,000 | 2 Mar | [193] |

| Mukacheve | 3,000 | 24 Nov | [194] |

| Odesa | 10,000 | 2 Mar | [195] |

| Khmelnytskyi | 8,000 | 24 Jan | [185] |

| Bila Tserkva | 2,000+ | 24 Jan | [196] |

| Sambir | 2,000+ | 1 Dec | [197] |

| Vinnytsia | 5,000 | 8 Dec 22 Jan | [198] |

| Zhytomyr | 2,000 | 23 Jan | [199] |

| Kirovohrad | 1,000 | 8 Dec 24 Jan | [188][200] |

| Kryvyi Rih | 1,000 | 1 Dec | [201] |

| Luhansk | 1,000 | 8 Dec | [202] |

| Uzhhorod | 1,000 | 24 Jan | [203] |

| Drohobych | 500–800 | 25 Nov | [204] |

| Kherson | 2,500 | 3 Mar | [205] |

| Mariupol | 400 | 26 Jan | [206] |

| Chernihiv | 150–200 | 22 Nov | [207] |

| Izmail | 150 | 22 Feb | [208] |

| Vasylkiv | 70 | 4 Dec | [209] |

| Yalta | 50 | 20 Feb | [210] |

A 24 November 2013 protest in Ivano-Frankivsk saw several thousand protestors gather at the regional administration building.[211] No classes were held in the universities of western Ukrainian cities such as Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk and Uzhhorod.[212] Protests also took place in other large Ukrainian cities, such as Kharkiv, Donetsk, Dnipropetrovsk (now Dnipro), and Luhansk. The rally in Lviv in support of the integration of Ukraine into the EU was initiated by the students of local universities. This rally saw 25–30 thousand protesters gather on Liberty Avenue in Lviv. The organisers planned to continue this rally until the 3rd Eastern Partnership summit in Vilnius, Lithuania, on 28–29 November 2013.[213] A rally in Simferopol, which drew around 300, saw nationalists and Crimean Tatars unite to support European integration; the protesters sang both the Ukrainian national anthem and the anthem of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen.[214]

7 people were injured after a tent encampment in Dnipropetrovsk was ordered cleared by court order on 25 November and it appeared that thugs had undertaken to perform the clearance.[215][216] Officials estimated the number of attackers to be 10–15,[217] and police did not intervene in the attacks.[218] Similarly, police in Odesa ignored calls to stop the demolition of Euromaidan camps in the city by a group of 30, and instead removed all parties from the premises.[219] 50 police officers and men in plain clothes also drove out a Euromaidan protest in Chernihiv the same day.[220]

On 25 November, in Odesa, 120 police raided and destroyed a tent encampment made by protesters at 5:20 in the morning. The police detained three of the protesters, including the leader of the Odesa branch of Democratic Alliance, Alexei Chorny. All three were beaten in the police vehicle and then taken to the Portofrankovsk Police Station without their arrival being recorded. The move came after the District Administrative Court earlier issued a ban restricting citizens' right to peaceful assembly until New Year. The court ruling places a blanket ban on all demonstrations, the use of tents, sound equipment and vehicles until the end of the year.[221]

On 26 November, a rally of 50 was held in Donetsk.[222]

On 28 November, a rally was held in Yalta; university faculty who attended were pressured to resign by university officials.[223]

On 29 November, Lviv protesters numbered some 20,000.[224] Like in Kyiv, they locked hands in a human chain, symbolically linking Ukraine to the European Union (organisers claimed that some 100 people even crossed the Ukrainian-Polish border to extend the chain to the European Union).[224][225]

On 1 December, the largest rally outside of Kyiv took place in Lviv by the statue of Taras Shevchenko, where over 50,000 protesters attended. Mayor Andriy Sadovy, council chairman Peter Kolody, and prominent public figures and politicians were in attendance.[63] An estimated 300 rallied in the eastern city of Donetsk demanding that President Viktor Yanukovych and the government of Prime Minister Mykola Azarov resign.[226] Meanwhile, in Kharkiv, thousands rallied with writer Serhiy Zhadan during a speech, calling for revolution. The protest was peaceful.[227][228][229] Protesters claimed at least 4,000 attended,[230] with other sources saying 2,000.[231] In Dnipropetrovsk, 1,000 gathered to protest the EU agreement suspension, show solidarity with those in Kyiv, and demanded the resignation of local and metropolitan officials. They later marched, shouting "Ukraine is Europe" and "Revolution".[232] EuroMaidan protests were also held in Simferopol (where 150–200 attended)[233] and Odesa.[234]

On 2 December, in an act of solidarity, Lviv Oblast declared a general strike to mobilise support for protests in Kyiv,[235] which was followed by the formal order of a general strike by the cities of Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk.[236]

In Dnipropetrovsk on 3 December, a group of 300 protested in favour of European integration and demanded the resignation of local authorities, heads of local police units, and the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU).[237]

On 7 December it was reported that police were prohibiting those from Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk from driving to Kyiv.[238]

Protests on 8 December saw record turnout in many Ukrainian cities, including several in eastern Ukraine. in the evening, the fall of the monument to Lenin in Kyiv took place.[239]

On 9 December, a statue of Vladimir Lenin was destroyed in the town of Kotovsk in Odesa Oblast.[240] In Ternopil, Euromaidan organisers were prosecuted by authorities.[241]

The removal or destruction of Lenin monuments and statues gained particular momentum after the destruction of the Kyiv Lenin statue. The statue removal process was soon termed “Leninopad” (Ukrainian: Ленінопад, Russian: Ленинопад), literally meaning 'Leninfall' in English. Soon, activists pulled down a dozen monuments in the Kyiv region, Zhytomyr, Chmelnitcki, and elsewhere, or damaged them during the course of the Euromaidan protests into spring of 2014.[242] In other cities and towns, monuments were removed by organised heavy equipment and transported to scrapyards or dumps.[243]

On 14 December, Euromaidan supporters in Kharkiv voiced their disapproval of authorities fencing off Freedom Square from the public by covering the metal fence in placards.[244] From 5 December, they became victims of theft and arson.[245] A Euromaidan activist in Kharkiv was attacked by two men and stabbed twelve times. The assailants were unknown, but activists told the Kharkiv-based civic organisation Maidan that they believe the city's mayor, Gennady Kernes, to be behind the attack.[246]

On 22 December, 2,000 rallied in Dnipropetrovsk.[247]

In late December, 500 marched in Donetsk. Due to the regime's hegemony in the city, foreign commentators have suggested that, "For 500 marchers to assemble in Donetsk is the equivalent of 50,000 in Lviv or 500,000 in Kyiv."[248][better source needed] On 5 January, marches in support of Euromaidan were held in Donetsk, Dnipropetrovsk, Odesa, and Kharkiv, the latter three drawing several hundred and Donetsk only 100.[249]

On 11 January 2014, 150 activists met in Kharkiv for a general forum on uniting the nationwide Euromaidan efforts. A church where some were meeting was stormed by over a dozen thugs, and others attacked meetings in a book store, smashing windows and deploying tear gas to stop the Maidan meetings from taking place.[250]

On 22 January in Donetsk, two simultaneous rallies were held – one pro-Euromaidan and one pro-government. The pro-government rally attracted 600 attendees, compared to about 100 from the Euromaidan side. Police reports claimed 5,000 attended to support the government, compared to only 60 from Euromaidan. In addition, approximately 150 titushky appeared and encircled the Euromaidan protesters with megaphones and began a conflict, burning wreaths and Svoboda Party flags, shouting, "Down with fascists!", but were separated by police.[251] Meanwhile, Donetsk City Council pleaded with the government to take tougher measures against Euromaidan protesters in Kyiv.[252] Reports indicated a media blackout took place in Donetsk.[citation needed]

In Lviv on 22 January, amid the police shootings of protesters in the capital, military barracks were surrounded by protesters. Many of the protesters included mothers whose sons were serving in the military, who pleaded with them not to deploy to Kyiv.[253]

In Vinnytsia on 22 January, thousands of protesters blocked the main street of the city and the traffic. Also, they brought "democracy in coffin" to the city hall, as a present to Yanukovych.[254]

On 23 January. Odesa city council member and Euromaidan activist Oleksandr Ostapenko's car was bombed.[255] The Mayor of Sumy threw his support behind the Euromaidan movement on 24 January, laying blame for the civil disorder in Kyiv on the Party of Regions and Communists.[256]

The Crimean parliament repeatedly stated that because of the events in Kyiv it was ready to join autonomous Crimea to Russia. On 27 February, armed men seized the Crimean parliament and raised the Russian flag.[257] 27 February was later declared a day of celebration for the Russian Spetsnaz special forces by Vladimir Putin by presidential decree.[258]

In the beginning of March, thousands of Crimean Tatars in support of Euromaidan clashed with a smaller group of pro-Russian protesters in Simferopol.[259][260]

On 4 March 2014, a mass pro-Euromaidan rally was held in Donetsk for the first time. About 2,000 people were there. Donetsk is a major city in the far east of Ukraine and served as Yanukovych's stronghold and the base of his supporters. On 5 March 2014, 7,000–10,000 people rallied in support of Euromaidan in the same place.[261] After a leader declared the rally over, a fight broke out between pro-Euromaidan and 2,000 pro-Russian protesters.[261][262]

Occupation of administrative buildings

[edit]Starting on 23 January, several Western Ukrainian oblast (province) government buildings and Regional State Administrations (RSAs) were occupied by Euromaidan activists.[16] Several RSAs of the occupied oblasts then decided to ban the activities and symbols of the Communist Party of Ukraine and Party of Regions in their oblast.[17] In the cities of Zaporizhzhia, Dnipropetrovsk and Odesa, protesters also tried to take over their local RSAs.[16]

Protests outside Ukraine

[edit]

Smaller protests or Euromaidans have been held internationally, primarily among the larger Ukrainian diaspora populations in North America and Europe. The largest took place on 8 December 2013 in New York, with over 1,000 attending. Notably, in December 2013, Warsaw's Palace of Culture and Science,[263] Cira Centre in Philadelphia,[264] the Tbilisi City Assembly in Georgia,[265] and Niagara Falls on the US-Canada border were illuminated in blue and yellow as a symbol of solidarity with Ukraine.[266]

Antimaidan and pro-government rallies

[edit]Pro-government rallies during Euromaidan were largely credited as funded by the government.[267][268] Several news outlets investigated the claims to confirm that by and large, attendees at pro-government rallies did so for financial compensation and not for political reasons, and were not an organic response to the Euromaidan. "People stand at Euromaidan protesting against the violation of human rights in the state, and they are ready to make sacrifices," said Oleksiy Haran, a political scientist at Kyiv Mohyla Academy in Kyiv. "People at Antimaidan stand for money only. The government uses these hirelings to provoke resistance. They won't be sacrificing anything."[269]

Euromaidan groups

[edit]Automaidan

[edit]Automaidan[270] was a movement within Euromaidan that sought the resignation of Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych. It was made up mainly of drivers who would protect the protest camps and blockade streets. It organised a car procession on 29 December 2013 to the president's residence in Mezhyhirya to voice their protests at his refusal to sign the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement in December 2013. The motorcade was stopped a couple of hundred metres short of his residence. Automaidan was the repeated target of violent attacks by government forces and supporters.[citation needed]

Self-defence groups

[edit]

On 30 November 2013, the day after the dispersion of the first major protests, Euromaidan activists, with the support of pro-Maidan political parties such as Svoboda, and aided by the Ukrainian politician and businessman Arsen Avakov,[271] created a self-defence group entitled “Self-Defence of the Maidan" or “Maidan Self-Defence” – an independent police force that aimed to protect protesters from riot police and provide security within Kyiv.[272][273] At the time, the head of the group was designated as Andriy Parubiy.[274]

“Self-Defence of the Maidan” adhered to a charter that “promoted the European choice and unity of Ukraine”,[271] and were not officially allowed to mask themselves or carry weapons, although most men in the group did not adhere to such rules and groups of volunteers were mainly fractured under a centralised leadership. The group ran its headquarters from a former women’s shoe store in central Kyiv, organising patrols, recruiting new members, and taking queries from the public. The makeshift headquarters was run by volunteers from across Ukraine.[271] After the ousting of President Yanukovych, the group took on a much larger role, serving as the de facto police force in Kyiv in early 2014, as most police officers abandoned their posts for fears of reprisal.[271] Aiming to prevent looting or arson from tainting the success of Euromaidan, government buildings were among the first buildings to be protected by the group, with institutions such as the Verkhovna Rada (Parliament of Ukraine) and the National Bank of Ukraine under 24-hour supervision during this time.[271]

“Self-defence” groups such as “Self-Defence of the Maidan” were divided up into sotnias (plural: sotni) or 'hundreds', which were described as a "force that is providing the tip of the spear in the violent showdown with government security forces". The sotni take their name from a traditional form of Cossacks cavalry formation, and were also used in the Ukrainian People's Army, Ukrainian Insurgent Army, and Ukrainian National Army.[275]

Along with “Self-Defence of the Maidan”, there were also some "independent" divisions of enforcers (some of them were also referred to as sotnias and even as “Self-Defence” groups), like the security of the Trade Unions Building until 2 January 2014,[276] Narnia and Vikings from Kyiv City State Administration,[277] Volodymr Parasyuk's sotnia from Conservatory building,[278][279] although Andriy Parubiy officially asked such divisions to not term themselves as “Self-Defence” groups.[280]

Pravy Sektor coordinates its actions with Self-defence and is formally a 23rd sotnia,[281] although already had hundreds of members at the time of registering as a sotnia. Second sotnia (staffed by Svoboda's members) tends to dissociate itself from "sotnias of self-defence of Maidan".[282]

Some Russian citizens sympathetic to the opposition joined the protest movement as part of the Misanthropic Division, many of them later becoming Ukrainian citizens.[39]

Casualties

[edit]

Altogether, more than 100 people were killed and 2,500 injured.[283] The death toll included 108 protesters and 13 police officers.[71] Most of the deaths and injuries were during the Revolution of Dignity in February 2014.[citation needed]

In November 2015, the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court released a legal analysis of the Maidan protests, concluding that: "violence against protesters, including the excessive use of force causing death and serious injury as well as other forms of ill-treatment, was actively promoted or encouraged by the Ukrainian authorities" under Yanukovych.[71]

By June 2016, 55 people had been charged in relation to the deaths of Maidan protesters, including 29 former members of the Berkut special police, ten titushky and ten senior government officials.[71]

Press and medics injured by police attacks

[edit]A number of attacks by law enforcement agents on members of the media and medical personnel have been reported. Some 40 journalists were injured during the staged assault at Bankova Street on 1 December 2013. At least 42 more journalists were victims of police attacks at Hrushevskoho Street on 22 January 2014.[284] On 22 January 2014, Television News Service (TSN) reported that journalists started to remove their identifying uniform (vests and helmets), as they were being targeted, sometimes on purpose, sometimes accidentally.[285] Since 21 November 2013, a total of 136 journalists have been injured.[286]

On 21 January 2014, 26 journalists were injured, with at least two badly injured by police stun grenades;[287] 2 others were arrested by police.[288] On 22 January, a correspondent of Reuters, Vasiliy Fedosenko, was intentionally shot in the head by a marksman with rubber ammunition during clashes at Hrushevskoho Street.[289][290][291] Later, a journalist of Espresso TV Dmytro Dvoychenkov was kidnapped, beaten and taken to an unknown location, but later a parliamentarian was informed that he was finally released.[292] On 24 January, President Yanukovych ordered the release of all journalists from custody.[293] On 31 January, a video from 22 January 2014 was published that showed policemen in Berkut uniforms intentionally firing at a medic who raised his hands.[294] On 18 February 2014, American photojournalist Mark Estabrook was injured by Berkut forces, who threw two separate concussion grenades at him just inside the gate at the Hrushevskoho Street barricade, with shrapnel hitting him in the shoulder and lower leg. He continued bleeding all the way to Cologne, Germany for surgery. He was informed upon his arrival in Maidan to stay away from the hospitals in Kyiv to avoid Yanukovych's Berkut police capture (February 2014)[295][296][297]

Analysis

[edit]Public opinion about Euromaidan

[edit]

According to December 2013 polls (by three different pollsters), between 45% and 50% of Ukrainians supported Euromaidan, while between 42% and 50% opposed it.[298][299][300] The biggest support for the protest was found in Kyiv (about 75%) and western Ukraine (more than 80%).[298][301] Among Euromaidan protesters, 55% were from the west of the country, with 24% from central Ukraine and 21% from the east.[302]

In a poll taken on 7–8 December, 73% of protesters had committed to continue protesting in Kyiv as long as needed until their demands were fulfilled.[5] This number had increased to 82% as of 3 February 2014.[302] Polls also showed that the nation was divided in age: while a majority of young people were pro-EU, older generations (50 and above) more often preferred the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia.[303] More than 41% of protesters were ready to take part in the seizure of administrative buildings as of February, compared to 13 and 19 per cent during polls on 10 and 20 December 2013. At the same time, more than 50 per cent were ready to take part in the creation of independent military units, compared to 15 and 21 per cent during the past studies, respectively.[302]

According to a January poll, 45% of Ukrainians supported the protests, and 48% of Ukrainians disapproved of Euromaidan.[304]

In a March poll, 57% of Ukrainians said they supported the Euromaidan protests.[305]

A study of public opinion in regular and social media found that 74% of Russian speakers in Ukraine supported the Euromaidan movement, and a quarter opposed.[306]

Support for Euromaidan in Ukraine

[edit]

According to a 4 to 9 December 2013 study[298] by Research & Branding Group, 49% of all Ukrainians supported Euromaidan and 45% had the opposite opinion. It was mostly supported in Western (84%) and Central Ukraine (66%). A third (33%) of residents of South Ukraine and 13% of residents of Eastern Ukraine supported Euromaidan as well. The percentage of people who do not support the protesters was 81% in East Ukraine, 60% in South Ukraine[nb 10], in Central Ukraine 27% and in Western Ukraine 11%. Polls have shown that two-thirds of Kyivans supported the ongoing protests.[301]

A poll conducted by the Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Fund and Razumkov Center, between 20 and 24 December, showed that over 50% of Ukrainians supported the Euromaidan protests, while 42% opposed it.[300]

Another Research & Branding Group survey (conducted from 23 to 27 December) showed that 45% of Ukrainians supported Euromaidan, while 50% did not.[299] 43% of those polled thought that Euromaidan's consequences "sooner could be negative", while 31% of the respondents thought the opposite; 17% believed that Euromaidan would bring no negative consequences.[299]

An Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation survey of protesters conducted 7 and 8 December 2013 found that 92% of those who came to Kyiv from across Ukraine came on their own initiative, 6.3% was organised by a public movement, and 1.8% were organised by a party.[5][308] 70% Said they came to protest the police brutality of 30 November, and 54% to protest in support of the European Union Association Agreement signing. Among their demands, 82% wanted detained protesters freed, 80% wanted the government to resign, and 75% want president Yanukovych to resign and for snap elections.[5][309] The poll showed that 49.8% of the protesters are residents of Kyiv and 50.2% came from elsewhere in Ukraine. 38% Of the protesters are aged between 15 and 29, 49% are aged between 30 and 54, and 13% are 55 or older. A total of 57.2% of the protesters are men.[5][308]

In the eastern regions of Donetsk, Luhansk and Kharkiv, 29% of the population believe "In certain circumstances, an authoritarian regime may be preferable to a democratic one."[310][311]

According to polls, 11% of the Ukrainian population has participated in the Euromaidan demonstrations, and another 9% has supported the demonstrators with donations.[312]

Public opinion about EU integration

[edit]According to a 4 to 9 December 2013 study[298] by Research & Branding Group 46% of Ukrainians supported the integration of the country into EU, and 36% into the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia. Most support for EU integration could be found in West (81%) and in Central (56%) Ukraine; 30% of residents of South Ukraine and 18% of residents of Eastern Ukraine supported the integration with EU as well. Integration with the Customs Union was supported by 61% of East Ukraine and 54% of South Ukraine and also by 22% of Central and 7% of Western Ukraine.[citation needed]

According to a 7 to 17 December 2013 poll by the Sociological group "RATING", 49.1% of respondents would vote for Ukraine's accession to the European Union in a referendum, and 29.6% would vote against the motion.[313] Meanwhile, 32.5% of respondents would vote for Ukraine's accession to the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia, and 41.9% would vote against.[313]

Public opinion about joining the EU

[edit]According to an August 2013 study by a Donetsk company, Research & Branding Group,[314] 49% of Ukrainians supported signing the Association Agreement, while 31% opposed it and the rest had not decided yet. However, in a December poll by the same company, only 30% claimed that terms of the Association Agreement would be beneficial for the Ukrainian economy, while 39% said they were unfavourable for Ukraine. In the same poll, only 30% said the opposition would be able to stabilise the society and govern the country well, if coming to power, while 37% disagreed.[315]

Authors of the GfK Ukraine poll conducted 2–15 October 2013 claim that 45% of respondents believed Ukraine should sign an Association Agreement with the EU, whereas only 14% favoured joining the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia, and 15% preferred non-alignment. Full text of the EU-related question asked by GfK reads, "Should Ukraine sign the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement, and, in the future, become an EU member?"[316][317]

Another poll conducted in November by IFAK Ukraine for DW-Trend showed 58% of Ukrainians supporting the country's entry into the European Union.[318] On the other hand, a November 2013 poll by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology showed 39% supporting the country's entry into the European Union and 37% supporting Ukraine's accession to the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia.[319]

In December 2013, then Prime Minister of Ukraine Mykola Azarov refuted the pro-EU poll numbers claiming that many polls posed questions about Ukraine joining the EU, and that Ukraine had never been invited to join the Union,[320] but only to sign the European Union Association Agreement (a treaty between the EU and another country, in this case Ukraine).[321]

Comparison with the Orange Revolution

[edit]The Financial Times said the 2013 protests were "largely spontaneous, sparked by social media, and have caught Ukraine's political opposition unprepared" compared to their well-organised predecessors.[322] The hashtag #euromaidan (Ukrainian: #євромайдан, Russian: #евромайдан), emerged immediately on the first meeting of the protests and was highly useful as a communication instrument for protesters.[323]

Paul Robert Magocsi illustrated the effect of the Orange Revolution on Euromaidan, saying,

Was the Orange Revolution a genuine revolution? Yes it was. And we see the effects today. The revolution wasn't a revolution of the streets or a revolution of (political) elections; it was a revolution of the minds of people, in the sense that for the first time in a long time, Ukrainians and people living in territorial Ukraine saw the opportunity to protest and change their situation. This was a profound change in the character of the population of the former Soviet Union.[324]

Lviv-based historian Yaroslav Hrytsak also remarked on the generational shift,

This is a revolution of the generation that we call the contemporaries of Ukraine's independence (who were born around the time of 1991); it is more similar to the Occupy Wall Street protests or those in Istanbul demonstrations (of this year). It's a revolution of young people who are very educated, people who are active in social media, who are mobile and 90 percent of whom have university degrees, but who don't have futures.[107]

According to Hrytsak: "Young Ukrainians resemble young Italians, Czech, Poles, or Germans more than they resemble Ukrainians who are 50 and older. This generation has a stronger desire for European integration and fewer regional divides than their seniors."[325] In a Kyiv International Institute of Sociology poll taken in September, joining the European Union was mostly supported by young Ukrainians (69.8% of those aged 18 to 29), higher than the national average of 43.2% support.[326][327] A November 2013 poll by the same institute found the same result with 70.8% aged 18 to 29 wanting to join the European Union while 39.7% was the national average of support.[326] An opinion poll by GfK conducted 2–15 October found that among respondents aged 16–29 with a position on integration, 73% favoured signing an Association Agreement with the EU, while only 45% of those over the age of 45 favoured Association. The lowest support for European integration was among people with incomplete secondary and higher education.[316]

Escalation to violence

[edit]

In the early stages of Euromaidan, there was discussion about whether the Euromaidan movement constituted a revolution. At the time many protest leaders (such as Oleh Tyahnybok) had already used this term frequently when addressing the public. Tyahnybok called in an official 2 December press release for police officers and members of the military to defect to 'the Ukrainian revolution'.[328]

In a Skype interview with media analyst Andrij Holovatyj, Vitaly Portnikov, Council Member of the "Maidan" National Alliance and President and Editor-in-Chief of the Ukrainian television channel TVi, stated "EuroMaidan is a revolution and revolutions can drag on for years" and that "what is happening in Ukraine goes much deeper. It is changing the national fabric of Ukraine."[329]

On 10 December Yanukovych said, "Calls for a revolution pose a threat to national security."[330] Former Georgian president Mikhail Saakashvili has described the movement as "the first geopolitical revolution of the 21st century".[331]

Political expert Anders Åslund commented on this aspect,

Revolutionary times have their own logic that is very different from the logic of ordinary politics, as writers from Alexis de Tocqueville to Crane Brinton have taught. The first thing to understand about Ukraine today is that it has entered a revolutionary stage. Like it or not, we had better deal with the new environment rationally.[332]

Impact

[edit]Political impact

[edit]During the annual World Economic Forum meeting at the end of January 2014 in Davos (Switzerland) Ukrainian Prime Minister Mykola Azarov received no invitations to the main events; according to the Financial Times's Gideon Rachman because the Ukrainian government was blamed for the violence of the 2014 Hrushevskoho Street riots.[333]

A telephone call was leaked of US diplomat Victoria Nuland speaking to the US Ambassador to Ukraine, Geoffrey Pyatt about the future of the country, in which she said that Klitschko should not be in the future government, and expressed her preference for Arseniy Yatsenyuk, who became interim Prime Minister. She also casually stated "fuck the EU."[334][335] German chancellor Angela Merkel said she deemed Nuland's comment "completely unacceptable".[336] Commenting on the situation afterwards, State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki said that Nuland had apologized to her EU counterparts[337] while White House spokesman Jay Carney alleged that because it had been "tweeted out by the Russian government, it says something about Russia's role".[338]

In February 2014 IBTimes reported, "if Svoboda and other far-right groups gain greater exposure through their involvement in the protests, there are fears they could gain more sympathy and support from a public grown weary of political corruption and Russian influence on Ukraine."[339] In the following late October 2014 Ukrainian parliamentary election Svoboda lost 31 seats of the 37 seats it had won in the 2012 parliamentary election.[340][341] The other main far-right party Right Sector won 1 seat (of the 450 seats in the Ukrainian parliament) in the same 2014 election.[340] From 27 February 2014 till 12 November 2014 three members of Svoboda did hold positions in Ukraine's government.[342]

On 21 February, after negotiations between President Yanukovych and representatives of opposition with mediation of representatives of the European Union and Russia, the agreement "About settlement of political crisis in Ukraine" was signed. The agreement provided return to the constitution of 2004, that is to a parliamentary presidential government, carrying out early elections of the president until the end of 2014 and formation of "the government of national trust".[343] The Verkhovna Rada adopted the law on release of all detainees during protest actions. Divisions of "Golden eagle" and internal troops left the center of Kyiv. On 21 February, at the public announcement leaders of parliamentary opposition of conditions of the signed Agreement, representatives of "Right Sector" declared that they don't accept the gradualness of political reforms stipulated in the document, and demanded immediate resignation of the president Yanukovych—otherwise they intended to go for storm of Presidential Administration and Verkhovna Rada.[344]

On the night of 22 February activists of Euromaidan seized the government quarter[345] left by law enforcement authorities and made a number of new demands—in particular, immediate resignation of the president Yanukovych.[346] Earlier that day, they stormed into Yanukovych's mansion.[347]

On 23 February 2014, following the 2014 Ukrainian revolution, the Rada passed a bill that would have altered the law on languages of minorities, including Russian. The bill would have made Ukrainian the sole state language at all levels.[348] However, on the next week 1 March, President Turchynov vetoed the bill.[349]

Following the Protests, Euromaidan activists mobilized toward state transformation. Activists began to, "promote reforms, drafting and advocating for legislative proposals and monitoring reform implementations."[350]

Economic impact

[edit]The Prime Minister, Mykola Azarov, asked for 20 billion Euros (US$27 billion) in loans and aid from the EU[156] The EU was willing to offer 610 million euros (838 million US) in loans,[157] however Russia was willing to offer 15 billion US in loans.[157] Russia also offered Ukraine cheaper gas prices.[157] As a condition for the loans, the EU required major changes to the regulations and laws in Ukraine. Russia did not.[156]

Moody's Investors Service reported on 4 December 2013 "As a consequence of the severity of the protests, demand for foreign currency is likely to rise" and noted that this was another blow to Ukraine's already poor solvency.[351] First deputy Prime Minister Serhiy Arbuzov stated on 7 December Ukraine risked a default if it failed to raise $10 billion "I asked for a loan to support us, and Europe [the EU] agreed, but a mistake was made – we failed to put it on paper."[352]

On 3 December, Azarov warned that Ukraine might not be able to fulfill its natural gas contracts with Russia.[353] And he blamed the deal on restoring gas supplies of 18 January 2009 for this.[353]

On 5 December, Prime Minister Mykola Azarov stated that "money to finance the payment of pensions, wages, social payments, support of the operation of the housing and utility sector and medical institutions do not appear due to unrest in the streets" and he added that authorities were doing everything possible to ensure the timely financing of them.[354] Minister of Social Policy of Ukraine Natalia Korolevska stated on 2 January 2014 that these January 2014 payments would begin according to schedule.[355]

On 11 December, the second Azarov Government postponed social payments due to "the temporarily blocking of the government".[356] The same day Reuters commented (when talking about Euromaidan) "The crisis has added to the financial hardship of a country on the brink of bankruptcy" and added that (at the time) investors thought it more likely than not that Ukraine would default over the next five years (since it then cost Ukraine over US$1 million a year to insure $10 million in state debt).[357]

Fitch Ratings reported on 16 December that the (political) "standoff" had led to "greater the risk that political uncertainty will raise demand for foreign currency, causing additional reserve losses and increasing the risk of disorderly currency movement".[358] It also added "Interest rates rose sharply as the National Bank sought to tighten hryvnia liquidity."[358]

First Deputy Finance Minister Anatoliy Miarkovsky stated on 17 December the Ukrainian government budget deficit in 2014 could amount to about 3% with a "plus or minus" deviation of 0.5%.[359]

On 18 December, the day after an economical agreement with Russia was signed, Prime Minister Mykola Azarov stated, "Nothing is threatening stability of the financial-economic situation in Ukraine now. Not a single economic factor."[360] However, BBC News reported that the deal "will not fix Ukraine's deeper economic problems" in an article titled "Russian bailout masks Ukraine's economic mess".[361]

On 21 January 2014, the Kyiv City State Administration claimed that protests in Kyiv had so far caused the city more than 2 million US dollars worth of damage.[362] It intended to claim compensation for damage caused by all demonstrators, regardless of their political affiliation.[362]

On 5 February 2014, the hryvnia fell to a five-year low against the US dollar.[363]

On 21 February 2014, Standard & Poor's cut Ukraine's credit rating to CCC; adding that the country risked default without "significantly favourable changes".[364] Standard & Poor's analysts believed the compromise deal of the same day between President Yanukovych and the opposition made it "less likely Ukraine would receive desperately needed Russian aid, thereby increasing the risk of default on its debts".[365]

Social impact

[edit]In Kyiv, life continued "as normal" outside the "protest zone" (namely Maidan Nezalezhnosti).[366][367]

Before the Euromaidan demonstrations happened, Ukrainians did not have a strong and unified understanding of what it meant to be Ukrainian. There was confusion on whether a person should be considered Ukrainian on a civic or ethnographic basis. Most citizens of Ukraine during the Euromaidan perceived the protests as a battle against the regime. Therefore, the social impact that Euromaidan had on Ukrainians is a stronger sense of national identity and unity. Results from a survey shows that the people who identified themselves as Ukrainian after the Euromaidan grew by 10% compared to the survey conducted before the protests.[368]

"Euromaidan" was named Word of the Year for 2013 by modern Ukrainian language and slang dictionary Myslovo,[369] and the most popular neologism in Russia by web analytics company Public.ru.[370]

Cultural impact

[edit]According to a representative of the Kyiv History Museum, its collection in the Ukrainian House on the night of 18–19 February, after it was recaptured by the police from the protesters.[371] Eyewitnesses report seeing the police forces plundering and destroying the museum's property.[372]

Music of Maidan

[edit]

Leading Ukrainian performers sang the song "Brat za Brata" (English: "Brother for Brother") by Kozak System to support protesters. The song was one of the unofficial anthems of Euromaidan.[373]

Ukrainian-Polish band Taraka came up with a song dedicated to "Euromaidan" "Podaj Rękę Ukrainie" (Give a Hand to Ukraine). The song uses the first several words of the National anthem of Ukraine "Ukraine has not yet died".[374][375][376]

Among other tunes, some remakes of the Ukrainian folk song "Aflame the pine was on fire" appeared (Ukrainian: Горіла сосна, палала).[377][378]

The Ukrainian band Skriabin created a song dedicated to the revolutionary days of Maidan.[379] Another native of Kyiv dedicated a song to titushky.[380]

DJ Rudy Paulenko created a track inspired by events on Maidan called "The Battle at Maidan".[381]

Belarusian rock band Lyapis Trubetskoy's song "Warriors of Light" (Voiny Svieta) was one of the unofficial anthems of Maidan.[382]

Films on Maidan

[edit]A compilation of short films about the 2013 revolution named Babylon'13 was created.[383]

Polish and Ukrainian activists created a short film, "Happy Kyiv", editing it with the Pharrell Williams hit "Happy" and some shoots of Babylon'13.[384]

On 5 February 2014, a group of activist cinematographers initiated a series of films about the people of Euromaidan.[385]

The American filmmaker John Beck Hofmann made the film Maidan Massacre, about the sniper shootings. It premiered at the Siena International Film Festival, receiving the Audience Award.[386]

In 2014 Belarusian-Ukrainian filmmaker Sergei Loznitsa released the documentary Maidan. It was filmed by several cameramen instructed by Loznitsa during the revolution in 2013 and 2014 and depicts different aspects, from peaceful rallies to the bloody clashes between police and protesters.[387]

In 2015 Netflix released the documentary Winter on Fire: Ukraine's Fight for Freedom about the Euromaidan protests. The documentary shows the protests from the start until the resignation of Viktor Yanukovych. The movie won the Grolsch People's Choice Documentary Award at the 2015 Toronto International Film Festival.[388]

In 2016 the documentary Ukraine on Fire premiered at the Taormina Film Fest.[389] The central thesis of the film is that the events that led to the flight of Yanukovych in February 2014 were a coup d'état led by the USA.[390]

The Long Breakup premiered at the 2020 East Oregon Film Festival. This long term documentary about complex relationship between Ukraine and Russia tells about the Euromaidan and the Orange Revolution and moreover from the Crimea annexation and the Donbass War.[391]

Visual Arts at Maidan

[edit]

The protests attracted numerous photographers who documented everyday life and symbolic moments at Maidan.[392][393][394][395] The Maidan protest also attract support by visual artists including illustrator Sasha Godiayeva[396] and the painter Temo Svirely.[397]

Theatre

While many Ukrainian playwrights and directors had trained and worked in Russia during the 1990s and 2000s, for lack of opportunity in their home country, an increasing number of them - such as Natalia Vorozhbit and Maksim Kyrochkin - decided to return to Ukraine after the Euromaidan, to contribute to an emerging vibrant field of new drama, or Ukrainian New Drama.[398] There was also a noticeable shift towards writing in Ukrainian after 2014, whereas some bilingual Ukrainian dramatists had used Russian prior to 2014 in order to serve a greater audience base. Vorozhbit wrote a highly significant play about the Euromaidan, The Maidan Diaries, which opened at the Franko National Theatre (one of Ukraine's two national theatres; Franko is the Ukrainian language national theatre).[398]

Sport

[edit]The 2013–14 UEFA Europa League Round of 32 match of 20 February 2014 between FC Dynamo Kyiv and Valencia CF was moved by UEFA from Kyiv's Olimpiyskiy National Sports Complex to the GSP Stadium in Nicosia, Cyprus, "due to the security situation in the Ukrainian capital".[399][400]

On 19 February, the Ukrainian athletes competing in the 2014 Winter Olympics asked for and were refused permission by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to wear black arm bands to honour those killed in the violent clashes in Kyiv.[401] IOC president Thomas Bach offered his condolences "to those who have lost loved ones in these tragic events".[401]

On 19 February 2014, alpine skier Bohdana Matsotska refused to further participate in the 2014 Winter Olympics in protest against the violent clashes in Kyiv.[402] She and her father posted a message on Facebook stating "In solidarity with the fighters on the barricades of the Maidan, and as a protest against the criminal actions made towards the protesters, the irresponsibility of the president and his lackey government, we refuse further performance at the Olympic Games in Sochi 2014."[402]

On 4 March 2014, the 2013–14 Eurocup Basketball Round of 16 game between BC Budivelnyk Kyiv and JSF Nanterre was moved to Žalgiris Arena in Kaunas, Lithuania. On 5 March 2014, another Round of 16 game between Khimik Yuzhny and Aykon TED Ankara was moved to Abdi Ipekci Arena in Istanbul.[403]

Legacy

[edit]

In mid-October 2014, President Petro Poroshenko stated that 21 November (Euromaidan started on 21 November 2013) will be celebrated as "Day of Dignity and Freedom".[165]

As of February 2019, the Ukrainian government has broken ground on a new Maidan memorial that will run the length of Instytutska Street, now also known as Avenue of the Heavenly Hundred.[404]

On 10 January 2022 Russian President Vladimir Putin claimed that the protesters of the 2022 Kazakh protests had used "Maidan technologies".[405]

Slogans and symbols

[edit]

A chant that was commonly chanted among protesters was “Slava Ukraini! Heroiam slava!” - "Glory to Ukraine, Glory to Heroes!"[406] The chant has extended beyond Ukrainians and has been used by Crimean Tatars and Russians.[406][407]

The red-and-black battle flag of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) is another popular symbol among protesters, and the wartime insurgents have acted as a large inspiration for Euromaidan protesters.[408] Serhy Yekelchyk of the University of Victoria says the use of UPA imagery and slogans was more of a potent symbol of protest against the current government and Russia rather than adulation for the insurgents themselves, explaining "The reason for the sudden prominence of [UPA symbolism] in Kyiv is that it is the strongest possible expression of protest against the pro-Russian orientation of the current government."[409] The colours of the flag symbolise Ukrainian red blood spilled on Ukrainian black earth.[410]

Reactions

[edit]In a poll published on 24 February 2014 by the state-owned Russian Public Opinion Research Center, only 15% of those Russians polled said 'yes' to the question: "Should Russia react to the overthrow of the legally elected authorities in Ukraine?"[411]

Legal hearings and investigation

[edit]Investigation about Euromaidan was ongoing since December 2013 following the initial dispersal of student gathering on the night of 30 November. On 13 December 2013 the President Viktor Yanukovych and government officials announced that three high-ranking officials will be brought to justice.[412][413] The General Prosecutor's Office of Ukraine questioned a chairman of the Kyiv City State Administration Oleksandr Popov on 13 December and a Security Council secretary Andriy Klyuev on 16 December.[414] The announcement about ongoing investigation became public at the so-called "round table" negotiations initiated by former Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk.[415] On 14 December, both Sivkovych and Popov were officially temporarily relieved of their duties until conclusion of the investigation.[416]

On 17 December the Prosecutor General questioned an activist Ruslana Lyzhychko who informed that beside Popov under pre-trial investigation are Sivkovych, Koriak and Fedchuk.[417] On request of parliamentary opposition, Prosecutor General Viktor Pshonka read in Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian parliament) a report on investigation about dispersal of protesters on 30 November.[418] During the report the Prosecutor General acknowledged that members of public order militsiya "Berkut" "exceeded the use of force" after being provoked by protesters. Pshonka also noted that investigation has not yet determined who exactly ordered use of force.[419] Following the PG's report, the parliamentary opposition registered a statement on creation of provisional investigation committee in regards to actions of law enforcement agencies towards peaceful protests in Kyiv.[420]

Earlier, a separate investigation was started by the Security Service of Ukraine on 8 December 2013 about actions aimed at seizing state power in Ukraine.[421] In the context of the 1 December 2013 Euromaidan riots, the Prosecutor General informed that in calls for the overthrow of the government are involved member of radical groups.[422] During the events at Bankova, the Ukrainian militsiya managed to detained 9 people and after few days the Ministry of Internal Affairs announced that it considers Ukrainian organization Bratstvo (see Dmytro Korchynsky) to be involved in instigation of disorders, while no one out of the detained were members of that organization.[423][424]

Ukrainian mass media reported the results of forensic examinations, according to which, the government police Berkut was implicated in the murders of maidan protesters since, according to these forensic examinations, matches were found between the bullets extracted from the bodies of maidan protesters and the weapons of the government police Berkut.[425][426][427][428][429][430] The experts explained why no match between the bullets and the weapons, which had been assigned to the Berkut special force, had been found as a result of the examination of the bullets held in January 2015, whereas the examination carried out in December of the same year had showed such a match.[430][431]

See also

[edit]- Maidan casualties, also known as the Heavenly Hundred

- Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

- 2014 Ukrainian Regional State Administration occupations

- Cold War II

- National Guard of Ukraine

- Orange Revolution

- Paul Manafort's lobbying for Viktor Yanukovych and involvement in Ukraine

- Politics of Ukraine

- Rise up, Ukraine!

- Russian military intervention in Ukraine (2014–present)

- Ukraine without Kuchma

- Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement

- 2011–2013 Russian protests

- List of protests in the 21st century

- Order of the Heavenly Hundred Heroes

Notes

[edit]- ^ On 1 December 2013 Kyiv's Town Hall became occupied by Euromaidan protesters; this forced the Kyiv City Council to meet in the Solomianka Raion state administration building instead.[12]

- ^ There was no legal basis for these bans since in Ukraine only a court can ban the activities of a political force.[18]

- ^ Reports of some protesters attending under duress from superiors[46]

- ^ Titushky are provocators during protests.[50]

- ^ Early November 2012 Communist Party party leader Petro Symonenko stated that his party will not co-operate with other parties in the new parliament elected in the 2012 Ukrainian parliamentary election.[56] Nevertheless, in at the time in parliament its parliamentary faction usually voted similarly to the Party of Regions parliamentary faction.[57]

- ^ The term Euromaidan; was initially used as a hashtag on Twitter.[84] A Twitter account named Euromaidan was created on the first day of the protests.[85] It soon became popular in the international media.[86] It is composed of two parts: Euro is short for Europe and maidan refers to Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), the main square of Kyiv, where the protests were centered.[84]

- ^ On 7 April 2013 a decree by Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych freed Yuriy Lutsenko from prison and exempted him from further punishment.[127]

- ^ On 20 December 2013 Ukrainian Prime Minister Mykola Azarov stated that the public had not been given clear explanations by the authorities of the reason of the decree suspended preparations for signing of the association agreement.[143]

- ^ On 10 December President Yanukovych stated "We will certainly resume the IMF negotiations. If there are conditions that suit us, we will take that path."[148] However, Yanukovych also (once again) stated that the conditions put forward by the IMF were unacceptable "I had a conversation with U.S. Vice President Joseph Biden, who told me that the issue of the IMF loan has almost been solved, but I told him that if the conditions remained ... we did not need such loans."[148]

- ^ According to the Financial Times, people in East Ukraine and South Ukraine "tend to be more politically passive than their western counterparts. Locals say they still feel part of Ukraine and have no desire to reunite with Russia – nor are they likely to engage in conflict with the west".[307]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "EuroMaidan rallies in Ukraine – Nov. 21–23 coverage". Kyiv Post. 25 November 2013. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (3 February 2014). "Don't Let Putin Grab Ukraine". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 May 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

The current crisis in Ukraine began because of Russian foreign policy.

- ^ Calamur, Krishnadev (19 February 2014). "4 Things To Know About What's Happening in Ukraine". Parallels (World Wide Web log). NPR. Archived from the original on 18 June 2024. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Spolsky, Danylo. "One minister's dark warning and the ray of hope". Kyiv Post (editorial). Archived from the original on 21 January 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "Ukrainian opposition uses polls to bolster cause". Euronews. 13 December 2013. Archived from the original on 28 January 2014. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ "Where did the downfall of Ukraine's President Viktor Yanukovych begin?". Public Radio International. 24 February 2014. Archived from the original on 18 June 2024. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "Ukrainian opposition calls for President Yanukovych's impeachment". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 21 November 2013. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David M. (1 December 2013). "Thousands of Protesters in Ukraine Demand Leader's Resignation". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 June 2024. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ Bonner, Brian (21 November 2013). "Two petition drives take aim at Yanukovych". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "EuroMaidan passes an anti-Customs Union resolution". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 15 December 2013. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ Веб-сайт Кабміну теж уже не працює [Cabinet Website also no longer works]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 11 November 2013. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "Hereha closes Kyiv City Council meeting on Tuesday". Interfax-Ukraine. 24 December 2013. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "Party of Regions, Communist Party banned in Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil regions". Kyiv Post. 27 January 2014. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "Activity of Regions Party, Communist Party, Yanukovych's portraits banned in Drohobych". Kyiv Post. 21 February 2014. Archived from the original on 29 June 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "Jailed Ukrainian opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko has been freed from prison, says official from her political party". CNN. 22 February 2014. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "Ukraine protests 'spread' into Russia-influenced east". BBC News. 26 January 2014. Archived from the original on 18 June 2024. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ a b Thousands mourn Ukraine protester amid unrest Archived 28 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Al Jazeera (26 January 2014)

- ^ Dangerous Liasons Archived 3 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Ukrainian Week (18 May 2015)

- ^ "Ukraine's PM Azarov and government resign". BBC. 28 January 2014. Archived from the original on 28 January 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ "Law on amnesty of Ukrainian protesters to take effect on Feb 17" Archived 21 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Interfax-Ukraine (17 February 2014)

- ^ "Ukraine lawmakers offer protester amnesty". The Washington Post. 29 January 2014. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine: Amnesty law fails to satisfy protesters". Euronews. 30 January 2014. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ Halya Coynash (30 January 2014). "Ruling majority takes hostages through new 'amnesty law'". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ Ukraine parliament passes protest amnesty law Archived 22 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. 29 January 2014

- ^ "Ukraine leader's sick leave prompts guessing game". South China Morning Post. Associated Press. 30 January 2014. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Ukraine president Viktor Yanukovych takes sick leave as amnesty, other moves fail to quell Kyiv protests Archived 31 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine. CBS news. 30 January 2014

- ^ Cabinet resumed preparations for the association with the EU Archived 12 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Ukrinform. 2 March 2014

- ^ Pravda, Ukrainska (2 February 2014). "Evidence shows falsified reports used against AutoMaidan - Feb. 02, 2014". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ "Українські студенти підтримали Євромайдан. У Києві та регіонах – страйки" [Ukrainian students supported Yevromaydan. In Kyiv and regions – Strikes]. NEWSru. UA. 26 November 2013. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: Key players". BBC News. 27 January 2014. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ "Kiev's protesters: Ukraine uprising was no neo-Nazi power-grab". The Guardian. 13 March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 June 2024. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Свобода, Радіо (19 January 2014). ""Правий сектор" підтверджує свою участь у подіях на Грушевського". Радіо Свобода (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ На Евромайдане в Киеве собрались десятки тысяч украинцев [Euromaydan in Kyiv gathered tens of thousands of Ukrainians] (in Russian). Korrespondent.net. 24 November 2013. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ "Mr Akhtem Chiygoz: "Crimean Tatars Leave Actively to Kyiv on Maidan Nezalezhnosti"". 3 December 2013. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Ivakhnenko, Vladimir (6 December 2013). Майдан готовит Януковичу вече [Square prepare Yanukovych Veche]. Svoboda (in Russian). Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ Об'єднані ліві йдуть з Майдану (tr. "The United Left is leaving the Maidan") Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (18 March 2014)

- ^ "Danyluks group under fire for seizure of government buildings". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 28 January 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ В'ячеслав Березовський: Євромайдани України стали потужним об'єднавчим чинником [Vyacheslav Berezovsky: Euromaydan Ukraine became a powerful unifying factor] (in Ukrainian). UA: Cun. 2 December 2013. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ a b Hrytsenko, Anya (30 September 2016). "Misanthropic Division: A Neo-Nazi Movement from Ukraine and Russia". Euromaidan Press. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Novogrod, James (21 February 2014). "Dozens of Ukrainian Police Defect, Vow to Protect Protesters". NBC News. Archived from the original on 27 June 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Nemtsova, Anna (13 December 2013). "Kiev's Military Guardian Angels". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ Post, Kyiv (27 January 2014). "EuroMaidan rallies in Ukraine (Jan. 26-27 live updates) - Jan. 27, 2014". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Під час штурму Банкової постраждали вже 15 правоохоронців [During the storming of Bankova, 15 law enforcement officers were injured]. TVi (in Ukrainian). 1 December 2013. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014.