Europeans in Medieval China

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 34 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 34 min

Given textual and archaeological evidence, it is thought that thousands of Europeans lived in Imperial China during the Yuan dynasty.[1] These were people from countries traditionally belonging to the lands of Christendom during the High to Late Middle Ages who visited, traded, performed Christian missionary work, or lived in China. This occurred primarily during the second half of the 13th century and the first half of the 14th century, coinciding with the rule of the Mongol Empire, which ruled over a large part of Eurasia and connected Europe with their Chinese dominion of the Yuan dynasty.[a] Whereas the Byzantine Empire centered in Greece and Anatolia maintained rare incidences of correspondence with the Tang, Song and Ming dynasties of China, the Holy See sent several missionaries and embassies to the early Mongol Empire as well as to Khanbaliq (modern Beijing), the capital of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China. These contacts with the West were preceded by rare interactions between the Han dynasty and Hellenistic Greeks and Romans.

Mainly located in places such as the Yuan capital of Karakorum, European missionaries and merchants traveled around various parts of the Yuan dynasty and other Mongol-ruled khanates during a period of time referred to by historians as the "Pax Mongolica". Perhaps the most important political consequence of this movement of peoples and intensified trade was the Franco-Mongol alliance, although the latter never fully materialized, at least not in a consistent manner.[2] The establishment of the Ming dynasty in 1368 and reestablishment of ethnic Han rule led to the cessation of European merchants and Roman Catholic missionaries living in China. Direct contact with Europeans was not renewed until Portuguese explorers and Jesuit missionaries arrived on Ming China's southern shores in the 1510s, during the Age of Discovery.

The Italian merchant Marco Polo, preceded by his father and uncle Niccolò and Maffeo Polo, traveled to China during the Yuan dynasty. Marco Polo wrote a famous account of his travels there, as did the Franciscan friar Odoric of Pordenone and the merchant Francesco Balducci Pegolotti. The author John Mandeville also wrote about his travels to China, but he may have based these on preexisting accounts. In Khanbaliq, the Roman archdiocese was established by John of Montecorvino, who was later succeeded by Giovanni de Marignolli. Other Europeans such as André de Longjumeau managed to reach the eastern borderlands of China in their diplomatic travels to the Yuan imperial court, while others such as Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, Benedykt Polak, and William of Rubruck traveled instead to Outer Mongolia. The Turkic Chinese Nestorian Christian Rabban Bar Sauma was the first diplomat from China to reach the royal courts of Christendom in the West.

Background

[edit]

Righthand image: Two Buddhist monks on a mural of the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves near Turpan, Xinjiang, China, 9th century AD; although Albert von Le Coq (1913) assumed the blue-eyed, red-haired monk was a Tocharian,[6] modern scholarship has identified similar Caucasian figures of the same cave temple (No. 9) as ethnic Sogdians,[7] an Eastern Iranian people who inhabited Turpan as an ethnic minority community during the phases of Tang Chinese (7th–8th century) and Uyghur rule (9th–13th century).[8]

Hellenistic Greeks

[edit]Before the 13th century AD, instances of Europeans going to China or of Chinese going to Europe were very rare.[1] Euthydemus I, Hellenistic ruler of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom in Central Asia during the 3rd century BC, led an expedition into the Tarim Basin (modern Xinjiang, China) in search of precious metals.[9][10] Greek influence as far east as the Tarim Basin at this time also seems to be confirmed by the discovery of the Sampul tapestry, a woolen wall hanging with the painting of a blue-eyed soldier, possibly a Greek, and a prancing centaur, a common Hellenistic motif from Greek mythology.[11] However, it is known that other Indo-European peoples such as the Yuezhi, Saka,[12] and Tocharians[13] inhabited the Tarim Basin before and after it was brought under Han Chinese influence during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BC).[14] Emperor Wu's diplomat Zhang Qian (d. 113 BC) was sent to forge an alliance with the Yuezhi, a mission that was unsuccessful, but he brought back eyewitness reports of legacies of Hellenistic Greek civilization with his travels to "Dayuan" in the Fergana Valley, with Alexandria Eschate as its capital, and the "Daxia" of Bactria, in what is now Afghanistan and Tajikistan.[15] Later the Han captured Dayuan in the Han-Dayuan war.[16][17] It has also been suggested that the Terracotta Army (sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang, first Emperor of China; dated to ~210 BCE), in the Xi'an region of Shaanxi Province, might be inspired by Hellenistic sculptural art,[18] a hypothesis that has caused some controversy.[19]

At the cemetery in Sampul (Shanpula; 山普拉), ~14 km from Khotan (now in Lop County, Hotan Prefecture, Xinjiang),[20] where the aforementioned Sampul tapestry was found,[5] the local inhabitants buried their dead there from roughly 217 BC to 283 AD.[21] Mitochondrial DNA analysis of the human remains has revealed genetic affinities to peoples from the Caucasus, specifically a maternal lineage linked to Ossetians and Iranians, as well as an Eastern-Mediterranean paternal lineage.[20][22] Seeming to confirm this link, from historical accounts it is known that Alexander the Great, who married a Sogdian woman from Bactria named Roxana,[23][24] encouraged his soldiers and generals to marry local women; consequentially, the later kings of the Seleucid Empire and Greco-Bactrian Kingdom had a mixed Persian-Greek ethnic background.[25][26][27][b]

Ancient Romans

[edit]Beginning in the age of Augustus (r. 27 BC – 14 AD), the Romans, including authors such as Pliny the Elder, mentioned contacts with the Seres, whom they identified as the producers of silk from distant East Asia and could have been the Chinese or even any number of middlemen of various ethnic backgrounds along the Silk Road of Central Asia and Northwest China.[28] The Eastern-Han era Chinese general Ban Chao, Protector General of the Western Regions, explored Central Asia and in 97 AD dispatched his envoys Gan Ying to Daqin (i.e. the Roman Empire).[29] Gan was dissuaded by Parthian authorities from venturing further than the "west coast" (possibly the Eastern Mediterranean) although he wrote a detailed report about the Roman Empire, its cities, postal network and consular system of government, and presented this to the Han court.[30]

Subsequently, there was a series of Roman embassies in China lasting from the 2nd to 3rd centuries AD, as recorded in Chinese sources. In 166 AD the Book of Later Han records that Romans reached China from the maritime south and presented gifts to the court of Emperor Huan of Han (r. 146–168 AD), claiming they represented Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Andun 安敦, r. 161–180 AD).[31] There is speculation that they were Roman merchants instead of official diplomats.[32]

At the very least, archaeological evidence supports the claim in the Weilüe[33] and Book of Liang[34] that Roman merchants were active in Southeast Asia, if not the claim of their embassies arriving in China through Jiaozhi, the Chinese-controlled province of northern Vietnam.[35] Roman golden medallions from the reigns of Antoninus Pius and his adopted son Marcus Aurelius have been found in Oc Eo (in the Mekong Delta, near the modern Ho Chi Minh City), a territory that belonged to the Kingdom of Funan bordering Jiaozhi.[35] Suggestive of even earlier activity is a Republican-era Roman glass bowl unearthed from a Western Han tomb of Guangzhou (on the shores of the South China Sea) dated to the early 1st century BC,[36] in addition to ancient Mediterranean goods found in Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia.[35] The Greco-Roman geographer Ptolemy wrote in his Antonine-era Geography that a Greek mariner named Alexander had reached a port city beyond the Golden Chersonese (Malay Peninsula, which Ptolemy named as Kattigara; given the archaeological evidence, this could have been Oc Eo,[35][37] although Ferdinand von Richthofen assumed it was Chinese-controlled Hanoi.[38] Roman coins have been found in China, but far fewer than in India.[39]

It is possible that a group of Greek acrobatic performers, who claimed to be from a place "west of the seas" (i.e. Roman Egypt, which the Book of Later Han related to the "Daqin" empire), were presented by a king of Burma to Emperor An of Han in 120 AD.[40] It is known that in both the Parthian Empire and Kushan Empire of Asia, ethnic Greeks continued to be employed as entertainers such as musicians and athletes who engaged in athletic competitions.[41][42]

Byzantine Empire

[edit]

Byzantine Greek historian Procopius stated that two Nestorian Christian monks eventually uncovered how silk was made. From this revelation, monks were sent by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian (ruled 527–565) as spies on the Silk Road from Constantinople to China and back to steal the silkworm eggs.[43] This resulted in silk production in the Mediterranean, particularly in Thrace, in northern Greece,[44] and gave the Byzantine Empire a monopoly on silk production in medieval Europe until the loss of its territories in Southern Italy. The Byzantine historian Theophylact Simocatta, writing during the reign of Heraclius (r. 610–641), relayed information about China's geography, including its capital city Khubdan (Old Turkic: Khumdan, i.e. Chang'an) and its ruler Taisson whose name meant "Son of Heaven" (Chinese: 天子 Tianzi, although this could be derived from the name of Emperor Taizong of Tang). Theophylact described accurately how China had been divided, by a border along the Yangzi River, into two warring nations, and how its reunification (under the Sui dynasty of 581–618) had coincided with the reign of the Byzantine emperor Maurice. [45]

The Chinese Old Book of Tang and New Book of Tang mention several embassies made by Fu lin (拂菻; i.e. Byzantium), which they equated with Daqin (i.e. the Roman Empire), beginning in 643 with an embassy sent by the king Boduoli (波多力, i.e. Constans II Pogonatos) to Emperor Taizong of Tang, bearing gifts such as red glass.[34] These histories also provided cursory descriptions of Constantinople, its walls, and how it was besieged by Da shi (大食; the Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate) and their commander "Mo-yi" (摩拽; i.e. Muawiyah I, governor of Syria before becoming caliph), who forced them to pay tribute.[34] From Chinese records it is known that Michael VII Doukas (Mie li sha ling kai sa 滅力沙靈改撒) of Fu lin dispatched a diplomatic mission to China's Song dynasty that arrived in 1081, during the reign of Emperor Shenzong of Song.[34][46] Some Chinese during the Song period showed interest in countries to the west, such as the early 13th-century Quanzhou customs inspector Zhao Rugua, who described the ancient Lighthouse of Alexandria in his Zhu fan zhi.[47]

Merchants

[edit]

According to the 9th-century Book of Roads and Kingdoms by ibn Khordadbeh,[48] China was a destination for Radhanite Jews buying boys, female slaves and eunuchs from Europe. During the subsequent Song period there was also a community of Kaifeng Jews in China.[49] The Spaniard, Benjamin of Tudela (from Navarre) was a 12th-century Jewish traveler whose Travels of Benjamin recorded vivid descriptions of Europe, Asia, and Africa, preceding those of Marco Polo by a hundred years.

Polo, a 13th-century merchant from the Republic of Venice, describes his travels to Yuan-dynasty China and the court of Mongol ruler Kublai Khan, along with the preceding journeys made by Niccolò and Maffeo Polo, his father and uncle, respectively, in his Travels of Marco Polo. Polo related this account to Rustichello da Pisa around 1298 while they shared a Genoese prison cell following their capture in battle.[50][51] In his return trip to Persia from China (setting out from the port at Quanzhou in 1291), Marco Polo said that he accompanied the Mongol princess Kököchin in her intended marriage to Arghun, ruler of the Mongol Ilkhanate, but she instead married his son Ghazan following the former's sudden death.[52] Although Marco Polo's presence is omitted entirely, his story is confirmed by the 14th-century Persian historian Rashid-al-Din Hamadani in his Jami' al-tawarikh.[53]

Marco Polo accurately described geographical features of China such as the Grand Canal.[54] His detailed and accurate descriptions of salt production confirm that he had actually been in China.[c] Marco described salt wells and hills where salt could be mined, probably in Yunnan, and reported that in the mountains "these rascals ... have none of the Great Khan's paper money, but use salt instead ... They have salt which they boil and set in a mold ..."[56] Polo also remarked how the Chinese burned paper effigies shaped as male and female servants, camels, horses, suits of clothing and armor while cremating the dead during funerary rites.[57]

When visiting Zhenjiang in Jiangsu, China, Marco Polo noted that Christian churches had been built there.[58] His claim is confirmed by a Chinese text of the 14th century explaining how a Sogdian named Mar-Sargis from Samarkand founded six Nestorian Christian churches there in addition to one in Hangzhou during the second half of the 13th century.[58] Nestorian Christianity had existed in China earlier during the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) when a Persian monk named Alopen (Chinese: Āluósī; 阿羅本; 阿羅斯[citation needed]) came to the capital Chang'an in 653 to proselytize, as described in a dual Chinese and Syriac language inscription from Chang'an (modern Xi'an) dated to the year 781.[59]

Others were soon to follow. The Italian Franciscan friar John of Montecorvino took a journey starting in 1291, setting out from Tabriz to Ormus, sailing from there to China while accompanied by the Italian merchant Pietro de Lucalongo.[60] While Montecorvino became a bishop in Khanbaliq (Beijing), his friend Lucalongo continued to serve as a merchant there and donated a large amount of money to maintain the local Catholic Church.[61] Marco Polo mentioned the heavy presence of Genoese Italians at Tabriz (modern Iran), a city that Marco returned to from China via the Strait of Hormuz in 1293–1294.[62] John Mandeville, a mid-14th-century author and alleged Englishman from St Albans, claimed to have lived in China and even served at the Mongol khan's court.[63] However, certain parts of his accounts are considered dubious by modern scholars, with some conjecturing that he simply concocted his stories by using written accounts of China penned by other authors such as Odoric of Pordenone.[64]

In Zaytun, the first harbour of China, there was a small Genoese colony, mentioned in 1326 by André de Pérouse. The most famous Italian resident of the city was Andolo de Savignone, who was sent to the West by the Khan in 1336 to obtain "100 horses and other treasures."[65] Following Savignone's visit, an ambassador was dispatched to China with one superb horse, which was later the object of Chinese poems and paintings.[65]

Other Venetians lived in China, including one who brought a letter to the West from John of Montecorvino in 1305. In 1339 a Venetian named Giovanni Loredano is recorded to have returned to Venice from China. A tombstone was also discovered in Yangzhou, commemorating the death of Caterina Vilioni, daughter of Domenico, in 1342.[65] This is an important object, which offers tangible evidence to the presence of non-elite European Christian women in Yuan China.[66]

In about 1340, Francesco Balducci Pegolotti, a merchant from Florence, compiled a guide about trade in China[67] based on records from travellers who visited China (Pegolotti himself never went to China).[68] The guide notes the size of Khanbaliq (modern Beijing) and how merchants could exchange silver for Chinese paper money that could be used to buy luxury items such as silk.[69]

The History of Yuan (chapter 134) records that a certain Ai-sie (transliteration of either Joshua or Joseph) from the country of Fu lin (i.e. the Byzantine Empire), initially in the service of Güyük Khan, was well-versed in Western languages and had expertise in the fields of medicine and astronomy that convinced Kublai Khan to offer him a position as the director of medical and astronomical boards. Kublai Khan eventually honored him with the title of Prince of Fu lin (Chinese: 拂菻王; Fú lǐn wáng). His biography in the History of Yuan lists his children by their Chinese names, which are similar to the Christian names Elias (Ye-li-ah), Luke (Lu-ko), and Antony (An-tun), with a daughter named A-na-si-sz.[70]

Europeans of the 13th and 14th century called Northern China by place-names similar to "Cathay", while Southern China was called "Mangi" or "Manzi".[71]

Missionaries and diplomats

[edit]The Italian explorer and archbishop Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and Polish friar and traveler Benedykt Polak were the first papal envoys to reach Karakorum after being sent there by Pope Innocent IV in 1245.[72] The "Historia Mongalorum" was later written by Pian del Carpini, documenting his travels and a cursory history of the Mongols.[73] Catholic missionaries soon established a considerable presence in China, due to the religious tolerance of the Mongols, due in no small part to the Khan's own great tolerance and open encouragement of the development of trade and intellectual avocation. The 18th-century English historian Edward Gibbon commented on the Mongols' religious tolerance and went as far as to compare the "religious laws" of Genghis Khan to equivalent ideas propounded by the Enlightenment English philosopher John Locke.[74]

Oghul Qaimish, the widow of Güyük Khan, ruled as regent over the Mongol realm from 1249 to 1251.[75] In 1250 the French diplomats André de Longjumeau, Guy de Longjumeau, and Jean de Carcassonne arrived at her court located along the Emil River (on the Kazakh-Chinese border), bearing gifts and representing their sovereign Louis IX of France, who desired a military alliance.[76] Empress Qaimish viewed the gifts as tributary offerings and, in addition to gifts given in return, entrusted to Louis' diplomats, she sent the French monarch a letter demanding his submission as a vassal.[77]

The Franciscan missionary John of Montecorvino (Giovanni da Montecorvino[78]) was ordered to China by Pope Nicholas III in 1279.[79] Montecorvino arrived in China at the end of 1293,[80] where he later translated the New Testament into the Mongol tongue, and converted 6,000 people (probably mostly Alans, Turks, and Mongols rather than Chinese). He was joined by three bishops (Andre de Perouse, Gerard Albuini and Peregrino de Castello) and ordained archbishop of Beijing by Pope Clement V in 1307.[81] A community of Armenians in China sprang up during this period. They were converted to Catholicism by John of Montecorvino.[82] Following the death of John of Montecorvino, Giovanni de Marignolli was dispatched to Beijing to become the new archbishop from 1342 to 1346 in an effort to maintain a Christian influence in the region.[83] Marignolli, although not mentioned by name in the History of Yuan, is noted in that historical text as the "Frank" (Fulang) who provided the Yuan imperial court with an impressive war horse as a tributary gift.[80]

On 15 March 1314 the killings of Francis de Petriolo, Monaldo of Ancona, and Anthony of Milan occurred in China.[84] This was followed by the Killing of James, Quanzhou's bishop, in 1362. His predecessors were Andrew, Peregrinus, and Gerard.[85]

The Franciscan friar Odoric of Pordenone visited China.[86] Friars in Hangzhou and Zhangzhou were visited by Odorico.[87] His total travels took place from 1304 to 1330,[88] although he first returned to Europe in 1330.[89] China's Franciscans were mentioned in his writings, the Itinerarium.[90][91]

In 1333, John de Montecorvino was officially replaced by Nicolaus de Bentra, who was chosen by Pope John XXII.[92] There were complaints of the absence of the archbishop in 1338.[93] Toghon Temür (the last Mongol ruler of the Yuan dynasty in China before their retreat to Mongolia to form the Northern Yuan dynasty) sent an embassy including Genoese Italians to Pope Benedict XII in 1336, requesting a new archbishop.[94] The pope answered by sending legates and ecclesiastical leaders to Khanbaliq in 1342, which included Giovanni de Marignolli.[95]

In 1370, following the ousting of the Mongols from China and the establishment of the Chinese Ming dynasty, the Pope sent a new mission to China, comprising the Parisian theologian Guillaume du Pré as the new archbishop and 50 Franciscans. However, this mission disappeared, apparently eliminated.[96] The Ming Hongwu Emperor sent a diplomatic letter to the Byzantine Empire,[97] through a European in China named Nieh-ku-lun.[98] John V Palaiologos was the Byzantine Emperor at the time the message was sent by Hongwu,[99] with the proclamatory letter informing him about the establishment of the new Ming dynasty.[34] The message was sent to the Byzantine ruler in September 1371 when Hongwu met with the merchant Nieh-ku-lun (捏古倫) from Fu lin (Byzantium).[100] The Khanbaliq bishop Nicolaus de Bentra is speculated to be the same person as Nieh-ku-lun, for instance, by Emil Bretschneider in 1888.[101] More recently, Edward Luttwak (2009) also mused that Nicolaus de Bentra and this alleged Byzantine merchant Nieh-ku-lin were one and the same.[102]

Friar William of Parto, Cosmas, and John de' Marignolli were among the Catholic clerics in China.[103] The Oriens Christianus by Michel Le Quien (1661–1733) recorded the names of Khanbaliq's previous bishops and archbishops.[104]

Captives

[edit]For his travels from 1253 to 1255, the Franciscan friar William of Rubruck reported numerous Europeans in Central Asia. He described German prisoners who had been enslaved and forced to mine gold and manufacture iron weapons in the Mongol town of Bolat, near Talas, Kyrgyzstan.[105] In Karakorum, the Mongol capital, he met a Parisian named Guillaume Boucher, and Pâquette, a woman from the French city of Metz, who had both been captured in Hungary during the Mongol invasions of Europe. He also mentions Hungarians and Russians.[1]

Spread of Chinese gunpowder

[edit]William of Rubruck, a Flemish missionary who visited the Mongol court of Mongke Khan at Karakorum and returned to Europe in 1257, was a friend of the English philosopher and scientific thinker Roger Bacon. The latter recorded the earliest known European recipe for gunpowder in his Opus Majus of 1267.[106] This came more than two centuries after the first known Chinese description of the formula for gunpowder in 1044, during the Song dynasty.[107] The earliest use of Chinese prototype firearms occurred at an 1132 siege during the Jin-Song Wars,[108] whereas the oldest surviving bronze hand cannon dates to 1288 during the Yuan period.[109] Following the Mongol invasions of Japan (1274–1281), a Japanese scroll painting depicted explosive bombs used by Yuan-dynasty forces against their samurai.[110] By 1326 the earliest artistic depiction of a gun was made in Europe by Walter de Milemete.[111] Petrarch wrote in 1350 that cannons were then a common sight on the European battlefield.[112]

Diplomatic missions to Europe

[edit]

Rabban Bar Sauma, a Nestorian Christian Turkic Chinese born in Zhongdu (later Khanbaliq, Beijing, capital of the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty), China,[113] was sent to Europe in 1287 as an ambassador for Arghun, ruler of the Ilkhanate and grandnephew of Kublai Khan.[114] He was preceded by Isa Kelemechi, an Assyrian Nestorian Christian who worked as a court astronomer for Kublai Khan in Khanbaliq,[115] and was sent by Arghun to Pope Honorius IV in 1285.[116] A decade earlier, Bar Sauma had originally set out on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, passing through Gansu and Khotan in Northwest China, yet spent time in Armenia and Baghdad instead to avoid getting caught up in nearby armed conflicts.[117] He had been accompanied by Rabban Markos, another Uyghur Nestorian Christian from China who was elected as the Patriarch of the Eastern Church and advised Arghun Khan to have Bar Sauma lead the diplomatic mission to Europe.[118]

Bar Sauma, who spoke Chinese, Persian, and Old Uyghur, traveled with a cohort of Italians who served as translators, with Europeans communicating to him in Persian.[119] Bar Sauma is the first known person from China to reach Europe, where he convened with the Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos, Philip IV of France, Edward I of England, and Pope Nicholas IV (shortly after the death of Pope Honorius IV) to form an alliance against the Mamluk Sultanate.[120] Edward Luttwak depicts the arrival of these Nestorian envoys to the court of the Byzantine ruler Andronikos II as something akin to "receiving mail from his in-law in Beijing," since Kublai Khan was a grandson of Genghis Khan and Andronikos had two half-sisters who were married to great-grandsons of Genghis.[121] Moving further west, Bar Sauma witnessed a naval battle at the Bay of Naples, Italy in June 1287 between the Angevins and the Crown of Aragon, while being hosted by Charles Martel of Anjou, whose father Charles II of Naples was imprisoned in Aragon (in modern Spain) at the time.[122] Aside from his desire to see Christian sites, churches, and relics, Bar Sauma also showed a keen interest in the university life and curricula of Paris, which Morris Rossabi contends was rooted in how exotic it must have seemed from his perspective and educational background in Muslim Persia and Chinese Confucian teaching.[123] Although he managed to secure an audience with these leaders of Christendom and exchanged letters from them to Arghun Khan, none of these Christian monarchs were fully committed to an alliance with the latter.[117]

Renewed contacts during the Ming dynasty

[edit]

In 1368 the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty collapsed amid widespread internal revolt during the Red Turban Rebellion, whose ethnic Han leader would become the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty.[124] A formal resumption of direct trade and contact with Europeans would not be seen until the 16th century, initiated by the Portuguese during the Age of Discovery.[125] The first Portuguese explorer to land in southern China was Jorge Álvares, who in May 1513 arrived at Lintin Island in the Pearl River Delta to engage in trade.[126] This was followed by Rafael Perestrello, a cousin of the wife of Christopher Columbus, who landed at Guangzhou in 1516 after a voyage from newly conquered Portuguese Malacca.[127] Although the 1517 mission by Fernão Pires de Andrade ended in disaster and his imprisonment by Ming authorities, relations would be smoothed over by Leonel de Sousa, the first governor of the Portuguese trade colony at Macau, China, in the Luso-Chinese treaty of 1554.[128] The writings of Gaspar da Cruz, Juan Gonzáles de Mendoza, and Antonio de Morga all impacted the Western view and understanding of China at the time, offering intricate details about its society and items of trade.[129]

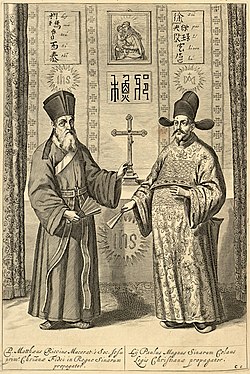

The Italian Jesuit missionary Michele Ruggieri would be the first European invited into the Ming-era Forbidden City in Beijing (during the reign of the Wanli Emperor); Matteo Ricci, in 1602 he would publish his map of the world in Chinese that introduced the existence of the American continents to Chinese geographers.[130] He arrived in Macau in 1582, when he began to learn the Chinese language and information about China's ancient culture, yet was unaware of the events that had transpired there since the end of the Franciscan missions in the mid 14th century and establishment of the Ming dynasty.[131] Since that time the Islamic world presented an obstacle for the West in reaching East Asia and, barring the grand treasure voyages of the 15th-century admiral Zheng He, the Ming dynasty had largely pursued policies of isolationism that kept it from seeking far-flung diplomatic contacts.[125][d]

See also

[edit]- Arcadio Huang, 17th-century Chinese visitor to Europe

- Cathay, medieval European name for China

- Fan Shouyi, 18th-century Chinese visitor to Europe

- Fonthill Vase, first Chinese porcelain ware to reach Europe

- Foreign relations of imperial China

- Giuseppe Castiglione (Jesuit painter), 18th-century Jesuit priest and court painter in China

- Hasekura Tsunenaga, 17th-century Japanese visitor to Europe

- Johann Adam Schall von Bell, 17th-century Jesuit priest in China

- Liqian (village)

- Michael Shen Fu-Tsung, 17th-century Chinese visitor to Europe

- Niccolò de' Conti, European explorer and merchant who travelled to India, Southeast Asia, and possibly China in the 15th century

- Nicolas Trigault, 17th-century Jesuit priest in China

- Orientalism in early modern France

- Wang Dayuan, Chinese visitor to North Africa in the 14th century

Notes

[edit]- ^ The term "Medieval China" is mainly used by historians of Universal History. The dates between 585 (Sui dynasty) to 1368 (Yuan dynasty) comprise the medieval period in Chinese history. Historians of Chinese history call this period the "Chinese Imperial Era", which began after the unification of the seven kingdoms by the Qin dynasty. With the Ming dynasty, the early modern era began.

- ^ Lucas Christopoulos writes the following: "The kings (or soldiers) of the Sampul cemetery came from various origins, composing as they did a homogenous army made of Hellenized Persians, western Scythians, or Sacae Iranians from their mother's side, just as were most of the second generation of Greeks colonists living in the Seleucid Empire. Most of the soldiers of Alexander the Great who stayed in Persia, India and central Asia had married local women, thus their leading generals were mostly Greeks from their father's side or had Greco-Macedonian grandfathers. Antiochos had a Persian mother, and all the later Indo-Greeks or Greco-Bactrians were revered in the population as locals, as they used both Greek and Bactrian scripts on their coins and worshipped the local gods. The DNA testing of the Sampul cemetery shows that the occupants had paternal origins in the eastern part of the Mediterranean."[22]

- ^ Some scholars have suggested that Polo's knowledge was so detailed that he must have been the imperial official in charge of the Yangzhou salt works, but this suggestion has not been accepted.[55]

- ^ The Ming Empire was at least willing to engage in conflicts nearby, however, when it offered relief forces to its tributary state Joseon (Korea) against invading Japanese forces in the Imjin War (1592–1598).[132]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Roux (1993), p. 465.

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P. (2004), Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, New York: Facts on File, Inc., p. 583, ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3.

- ^ Li, Song (2006), "From the Northern Song to the Qing", in Howard, Angela Falco (ed.), Chinese Sculpture, Yale University Press, p. 360, ISBN 978-0-3001-0065-5

- ^ Murata, Jirō (村田治郎) (1957). Chü-Yung-Kuan: The Buddhist Arch of the Fourteenth Century A.D. at the Pass of the Great Wall Northwest of Peking. Kyoto University Faculty of Engineering. p. 134.

- ^ a b Christopoulos (2012), pp. 15–16.

- ^ von Le Coq, Albert. (1913). Chotscho: Facsimile-Wiedergaben der Wichtigeren Funde der Ersten Königlich Preussischen Expedition nach Turfan in Ost-Turkistan. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), im Auftrage der Gernalverwaltung der Königlichen Museen aus Mitteln des Baessler-Institutes, Tafel 19. (Accessed 3 September 2016).

- ^ Gasparini, Mariachiara. "A Mathematic Expression of Art: Sino-Iranian and Uighur Textile Interactions and the Turfan Textile Collection in Berlin," in Rudolf G. Wagner and Monica Juneja (eds), Transcultural Studies, Ruprecht-Karls Universität Heidelberg, No 1 (2014), pp 134–163. ISSN 2191-6411. See also endnote #32. (Accessed 3 September 2016.)

- ^ Hansen (2012), p. 98.

- ^ Tarn (1966), pp. 109–111.

- ^ For Strabo's depiction of this event, see Christopoulos (2012), p. 8.

- ^ Christopoulos (2012), p. 15–16; Hansen (2012), p. 202; Feng (2004), p. 194–195.

- ^ Bailey (1996), p. 1230–1231; Tremblay (2007), p. 77; Yu (2010), p. 13-14, 21–22.

- ^ Mallory & Mair (2000), p. 270–297; Tremblay (2007), p. 77.

- ^ Torday (1997), p. 80–81; Yü (1986), p. 377–462; Chang (2007), p. 5–8; Di Cosmo (2002), p. 174–189, 196–198, 241–242.

- ^ Yang (2014).

- ^ "Why were China's horses of the ancient Silk Road so heavenly?". The Telegraph. 26 April 2019. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ Benjamin, Craig (May 2018). "Zhang Qian and Han Expansion into Central Asia". Empires of Ancient Eurasia. Empires of Ancient Eurasia: The First Silk Roads Era, 100 BCE – 250 CE. pp. 68–90. doi:10.1017/9781316335567.004. ISBN 978-1-3163-3556-7. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ "Western contact with China began long before Marco Polo, experts say". BBC News. 12 October 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Controversy about the-theory-that-greek-art-inspired-chinas-terracotta-army". The Conversation. 18 November 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ a b Xie, Chengzhi; et al. (August 2007). "Mitochondrial DNA analysis of ancient Sampula population in Xinjiang". Progress in Natural Science. 17: 927–933.

- ^ Christopoulos (2012), p. 27.

- ^ a b Christopoulos (2012), p. 27 footnote 46.

- ^ LIVIUS (2015); Strachan & Bolton (2008), p. 87.

- ^ For another publication calling her "Sogdian", see Christopoulos (2012), p. 4.

- ^ Holt (1989), pp. 67–68.

- ^ Ahmed (2004), p. 61.

- ^ Magill (1998), p. 1010.

- ^ Tarn (1966), pp. 110–111.

- ^ Yü (1986), p. 460–461; de Crespigny (2007), p. 239–240.

- ^ Wood (2002), p. 46–47; Morton & Lewis (2005), p. 59.

- ^ Yü (1986), p. 460–461; de Crespigny (2007), p. 600.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 600.

- ^ Yu (2004).

- ^ a b c d e Hirth (1885).

- ^ a b c d Young (2001), pp. 29–30.

- ^ An (2002), p. 83.

- ^ For further information on the archaeological site at Óc Eo in Vietnam, see: Osborne (2006), pp. 24–25

- ^ Richthofen, Ferdinand von (1877). China. Vol. I. Berlin. pp. 504–510.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) cited in Hennig, Richard (1944). Terrae incognitae : eine Zusammenstellung und kritische Bewertung der wichtigsten vorcolumbischen Entdeckungsreisen an Hand der daruber vorliegenden Originalberichte, Band I, Altertum bis Ptolemäus (in German). Leiden: Brill. pp. 387, 410–411. cited in Zürcher, Erik (2002). Traditionele bouwkunst in Taiwan [Traditional Architecture in Taiwan] (in Dutch). Antwerp-Apeldoorn: Garant. pp. 30–31. ISBN 9-05350-2025. - ^ Ball (2016), p. 154.

- ^ Ban Gu (班固), Houhanshu (後漢書) (Later Han dynasty annals), chap. 86, "Traditions of the Southern Savages; The South-Western Tribes" (Nanman, Xinanyi zhuan 南蠻西南夷列傳). Liezhuan 76. (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局, 1962–1999), p. 1926. "永初元年," 徼外僬僥種夷陸類等三千餘口舉種内附,献象牙、水牛、封牛。 永寧元年,撣國王雍由調复遣使者詣闕朝賀,献樂及幻人,能變化吐火,自支解,易牛馬頭。又善跳丸, 數乃至千。自言我海西人。海西即大秦也,撣國西南通大秦。明年元會,安帝作變於庭,封雍由調爲漢大 都尉,赐印綬、金銀、彩繒各有差也."

A translation of this passage into English, in addition to an explanation of how Greek athletic performers figured prominently in the neighboring Parthian and Kushan Empires of Asia, is offered by Christopoulos (2012), pp. 40–41:The first year of Yongning (120 AD), the southwestern barbarian king of the kingdom of Chan (Burma), Yongyou, proposed illusionists (jugglers) who could metamorphose themselves and spit out fire; they could dismember themselves and change an ox head into a horse head. They were very skilful in acrobatics and they could do a thousand other things. They said that they were from the "west of the seas" (Haixi–Egypt). The west of the seas is the Daqin (Rome). The Daqin is situated to the south-west of the Chan country. During the following year, Andi organized festivities in his country residence and the acrobats were transferred to the Han capital where they gave a performance to the court, and created a great sensation. They received the honours of the Emperor, with gold and silver, and every one of them received a different gift.

- ^ Christopoulos (2012), pp. 40–41.

- ^ Cumont (1933), pp. 264–268.

- ^ Durant (1949), p. 118.

- ^ LIVIUS (2010).

- ^ Yule & Cordier (1913), pp. 29–31.

- ^ Sezgin et al. (1996), p. 25.

- ^ Needham (1971), p. 662.

- ^ Hirschman, Elizabeth Caldwell; Yates, Donald N. (29 April 2014). The Early Jews and Muslims of England and Wales: A Genetic and Genealogical History. McFarland. pp. 51ff. ISBN 978-0-7864-7684-8.

- ^ Gernet (1962), p. 82.

- ^ Polo (1958), p. 16.

- ^ Hoffman (1991), p. 392.

- ^ Ye (2010), pp. 5–6.

- ^ Morgan (1996), pp. 221–225, 224.

- ^ Haw (2006), pp. 1–2.

- ^ Olschki (1960), p. 174.

- ^ Vogel (2013), pp. 290, 301–310.

- ^ Needham (1985), p. 105.

- ^ a b Emmerick (2003), p. 275.

- ^ Emmerick (2003), pp. 274–275.

- ^ Ciocîltan (2012), p. 120.

- ^ Ciocîltan (2012), p. 120, footnote 268.

- ^ Ciocîltan (2012), pp. 119–121.

- ^ Mandeville (1983), pp. 9–11.

- ^ Mandeville (1983), pp. 11–13.

- ^ a b c Roux (1993), p. 467.

- ^ Ilko (2024).

- ^ "Francesco Balducci Pegolotti." Encyclopædia Britannica (online source). Accessed 6 September 2016.

- ^ Yule & Cordier (1913), p. 283.

- ^ Spielvogel (2011), p. 183.

- ^ Bretschneider (1888), p. 144.

- ^ Wittfogel, Karl A.; Fêng 馮, Chia-Shêng 家昇 (1949). "History of Chinese Society: Liao (907–1125)". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 36. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 2. ISBN 978-1-4223-7719-2 – via Google Books.

{{cite journal}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Fontana (2011), p. 116; Buell (2010), p. 120–121.

- ^ Friedman & Figg (2013), p. 307ff; Buell (2003), p. 120–121.

- ^ Morgan (2007), p. 39.

- ^ Xu (1998), pp. 299–300.

- ^ Xu (1998), pp. 300–301.

- ^ Xu (1998), p. 301.

- ^ "ASIA/CHINA - Franciscans in China: 1200–1977, 1,162 Friars Minor lived in China". Agenzia Fides. 19 January 2010.

- ^ Herbermann (1913), p. 293ff; Clark (2011), p. 114ff.

- ^ a b Haw (2006), p. 172.

- ^ Fontana (2011), p. 116; Haw (2006), p. 172.

- ^ Bays (2011), p. 20ff; Kim (2011), p. 60ff.

- ^ Haw (2006), p. 52–57, 172; Encyclopædia Britannica (2016).

- ^ Robson (2006), p. 113.

- ^ Cordier (1908).

- ^ Haw (2006), pp. 52–57.

- ^ Robson (2006), p. 115.

- ^ Herbermann (1913), p. 553.

- ^ Fontana (2011), p. 116.

- ^ Buell (2003), p. 204.

- ^ Muscat, Noel. "6. History of the Franciscan Movement (4)". Christus Rex. FIOR-Malta. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016.

- ^ Hirth (1885); Mosheim (1832), p. 415ff.

- ^ Mosheim (1862), pp. 52ff.

- ^ Jackson (2005), p. 314.

- ^ Fontana (2011), p. 116; Jackson (2005), p. 314.

- ^ Roux (1993), p. 469.

- ^ Grant (2005), pp. 99ff.

- ^ Hirth (1885), p. 66.

- ^ Luttwak (2009), pp. 169ff.

- ^ Yule & Cordier (1913), pp. 12ff.

- ^ Yule & Cordier (1913), p. 13ff; Bretschneider (1871), p. 25ff.

- ^ Luttwak (2009), pp. 169–170.

- ^ Hakluyt Society (1967). Works. Kraus Reprint. p. 13.

- ^ Yule & Cordier (1913), p. 13.

- ^ Goody (2012), p. 226; Spence (1999), p. 1–2.

- ^ Pacey (1991), p. 45; Needham (1987), p. 48–50.

- ^ Ebrey (1996), p. 138; Needham (1987), p. 118–124.

- ^ Chase (2003), p. 31; Needham (1987), p. 222; Lorge (2008), p. 33–34.

- ^ Chase (2003), p. 32; Needham (1987), p. 293.

- ^ Turnbull (2013), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Kelly (2004), p. 29.

- ^ Norris (2003), p. 19.

- ^ Kuiper (2006); Carter (1955), p. 171; Moule (1914), pp. 94, 103; Pelliot (1914), p. 630–636.

- ^ Jackson (2005), p. 169.

- ^ Foltz (2010), p. 125–126; Glick, Livesey & Wallis (2005), p. 485.

- ^ Jackson (2005), p. 169; Fisher & Boyle (1968), p. 370.

- ^ a b Kuiper (2006).

- ^ Kuiper (2006); Rossabi (2014), p. 385–386.

- ^ Rossabi (2014), pp. 385–387.

- ^ Kuiper (2006); Rossabi (2014), p. 386–421; Fisher & Boyle (1968), p. 370–371.

- ^ Luttwak (2009), p. 169.

- ^ Rossabi (2014), p. 399.

- ^ Rossabi (2014), pp. 416–417.

- ^ Ebrey (1996), pp. 190–191.

- ^ a b Fontana (2011), p. 117.

- ^ Wills (1998), p. 336.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 124.

- ^ Wills (1998), pp. 338–444.

- ^ Robinson (2000), p. 527–563; Brook (1998), p. 206.

- ^ Abbe (2009).

- ^ Fontana (2011), pp. 18–35, 116–118.

- ^ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), p. 214.

Sources

[edit]- Abbe, Mary (18 December 2009). "Million-dollar map coming to Minnesota". Star Tribune. Minneapolis: Star Tribune Company. Retrieved 6 September 2016.[dead link]

- An, Jiayao (2002). "When Glass Was Treasured in China". In Juliano, Annette L.; Lerner, Judith A. (eds.). Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 79–94. ISBN 2-5035-2178-9.

- Ahmed, S. Z. (2004). Chaghatai: the Fabulous Cities and People of the Silk Road. West Conshokoken: Infinity Publishing.

- Bailey, H.W. (1996). Khotanese Saka Literature. in Yarshater (2003)

- Ball, Warwick (2016). Rome in the East: Transformation of an Empire (2nd ed.). London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-4157-2078-6.

- Bays, Daniel H. (9 June 2011). A New History of Christianity in China. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-4284-0.

- Bretschneider, Emil (1871). On the Knowledge Possessed by the Ancient Chinese of the Arabs and Arabian Colonies: And Other Western Countries, Mentioned in Chinese Books. Trübner & Company. pp. 25ff.

Nicholas, in the year 1338, had not yet arrived in Peking, for the christians there complained in a letter, written at the above date, that they were eight years without a curate.

- Bretschneider, Emil (1888). Medieval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources: Fragments Towards the Knowledge of the Geography and History of Central and Western Asia from the 13th to the 17th Century. Vol. 1. Abingdon: Routledge. (reprinted 2000)

- Brook, Timothy (1998). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-5202-2154-0. (Paperback)

- Buell, Paul D. (19 March 2003). Historical Dictionary of the Mongol World Empire. Scarecrow Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-0-8108-6602-7.

- Buell, Paul D. (12 February 2010). The A to Z of the Mongol World Empire. Scarecrow Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-1-4617-2036-2.

- Carter, Thomas Francis (1955). The invention of printing in China and its spread westward (2 ed.). Ronald Press Co. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-6081-1313-5. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Chang, Chun-shu (2007). The Rise of the Chinese Empire. Vol. II: Frontier, Immigration, & Empire in Han China, 130 B.C. – A.D. 157. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-4721-1534-1.

- Chase, Kenneth Warren (2003). Firearms: A Global History to 1700. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5218-2274-9.

- Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012). Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD). in Sino-Platonic Papers

- Ciocîltan, Virgil (2012). The Mongols and the Black Sea Trade in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9-0042-2666-1.

- Clark, Anthony E. (7 April 2011). China's Saints: Catholic Martyrdom During the Qing (1644–1911). Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-6114-6017-9.

- Cordier, Henri (1908). The Church in China. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton. Retrieved 6 September 2016 – via New Advent.

- Cumont, Franz (1933). The Excavations of Dura-Europos: Preliminary Reports of the Seventh and Eighth Seasons of Work. New Haven: Crai.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 978-9-0041-5605-0.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola (2002). Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5217-7064-4.

- Durant, Will (1949). The Age of Faith: The Story of Civilization. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4761-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5216-6991-7. OL 7751158M.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-6181-3384-4.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, ed. (6 September 2016). Giovanni dei Marignolli: Italian Clergyman. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Emmerick, R. E. (2003). Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs. in Yarshater (2003)

- Fisher, William Bayne; Boyle, John Andrew (1968). The Cambridge history of Iran. London & New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-5210-6936-X.

- Foltz, Richard (2010). Religions of the Silk Road (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-2306-2125-1.

- Fontana, Michela (2011). Matteo Ricci: a Jesuit in the Ming Court. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-0586-4.

- Friedman, John Block; Figg, Kristen Mossler (4 July 2013). Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middle Ages: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-1355-9094-9.

- Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Translated by Wright, H.M. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0720-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Glick, Thomas F; Livesey, Steven John; Wallis, Faith (2005). Medieval science, technology, and medicine: an encyclopedia. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-4159-6930-1.

- Goody, Jack (2012). Metals, Culture, and Capitalism: an Essay on the Origins of the Modern World. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-2962-0.

- Grant, R.G. (2005). Battle: A Visual Journey Through 5,000 Years of Combat. DK. ISBN 978-0-7566-1360-0.

- Hansen, Valerie (2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1951-5931-8.

- Haw, Stephen G. (2006). Marco Polo's China: a Venetian in the Realm of Kublai Khan. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-4153-4850-1.

- Herbermann, Charles George (1913). The Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church. Universal Knowledge Foundation.

- Hirth, Friedrich (1885). China and the Roman Orient: Researches Into Their Ancient and Mediaeval Relations as Represented in Old Chinese Records. G. Hirth. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-5240-3305-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Hoffman, Donald L. (1991). "Rusticiano da Pisa". In Lacy, Norris J. (ed.). The New Arthurian Encyclopedia. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-4377-4.

- Holt, Frank L. (1989). Alexander the Great and Bactria: the Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia. Leiden, New York, Copenhagen, Cologne: E. J. Brill. ISBN 9-0040-8612-9.

- Ilko, Krisztina (2024). "Yangzhou, 1342: Caterina Vilioni's Passport to the Afterlife". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (2): 1–36. doi:10.1017/S0080440124000136.

- Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West, 1221–1410. The Medieval World. Pearson. ISBN 978-0-5823-6896-5. OL 7880824M.

- Kelly, Jack (2004). Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World. Basic Books. ISBN 0-4650-3718-6.

- Kim, Heup Young (2011). Asian and Oceanic Christianities in Conversation: Exploring Theological Identities at Home and in Diaspora. Rodopi. ISBN 9-0420-3299-5.

- Kuiper, Kathleen (31 August 2006). Encyclopædia Britannica (ed.). Rabban bar Sauma: Mongol Envoy. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- LIVIUS (28 October 2010). Silk Road. Articles of Ancient History. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- LIVIUS (17 August 2015). Roxane. Articles on Ancient History. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- Lorge, Peter Allan (2008). The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5216-0954-8.

- Luttwak, Edward N. (2009). The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire. Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-6740-3519-5.

- Magill, Frank N.; et al. (1998). The Ancient World: Dictionary of World Biography. Vol. 1. Pasadena, Chicago, London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, Salem Press. ISBN 0-8935-6313-7.

- Mair, Victor H., ed. (2012). Sino-Platonic Papers. Vol. 230. Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. ISSN 2157-9687.

- Mallory, J.P.; Mair, Victor (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-5000-5101-6.

- Mandeville, John (1983). The Travels of Sir John Mandeville. Translated by Moseley, C.W.R.D. London: Penguin Books.

- Morgan, D.O. (July 1996). "Marco Polo in China-Or Not". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 6 (2): 221–225. doi:10.1017/S1356186300007203.

- Morgan, David (2007). The Mongols. Malden, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-3539-9.

- Morton, William Scott; Lewis, Charlton M. (2005). China: Its History and Culture (4th ed.). New York City: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-0714-1279-7.

- Mosheim, Johann Lorenz von (1832). Institutes of Ecclesiastical History: Ancient and Modern ... A. H. Maltby.

nicolaus de bentra.

- Mosheim, Johann Lorenz von (1862). Authentic Memoirs of the Christian Church in China. Adegi Graphics LLC. ISBN 978-1-4021-8109-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Moule, A. C. (1914). Christians in China before 1500. pp. 94 & 103.

- Needham, Joseph; et al. (1971). Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 4: Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3: Civil Engineering and Nautics. Cambridge, Taipei: Cambridge University Press, Caves Books.

- Needham, Joseph; et al. (1985), Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5 Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1: Paper and Printing, Cambridge University Press

- Needham, Joseph; et al. (1987). Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 5 Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7: Military technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5213-0358-3.

- Norris, John (2003). Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300–1600. Marlborough: The Crowood Press.

- Olschki, Leonardo (1960). Marco Polo's Asia: an Introduction to His "Description of the World" Called "Il Milione". Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Osborne, Milton (2006) [2000]. The Mekong: Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future (revised ed.). Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-7411-4893-6.

- Pacey, Arnold (1991). Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-year History. Boston: MIT Press. ISBN 0-2626-6072-5.

- Pelliot, Paul (1914). T'oung-pao. Vol. 15. pp. 630–636.

- Polo, Marco (1958). The Travels of Marco Polo. Translated by Latham, Ronald. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-1404-4057-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Robinson, David M. (Spring 2000). "Banditry and the Subversion of State Authority in China: The Capital Region during the Middle Ming Period (1450–1525)". Journal of Social History: 527–563.

- Robson, Michael (2006). The Franciscans in the Middle Ages. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-8438-3221-8.

- Rossabi, Morris (2014). From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi. Leiden & Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9-0042-8529-3.

- Roux, Jean-Paul (1993). Histoire de l'Empire Mongol. Fayard. ISBN 2-2130-3164-9.

- Sezgin, Fuat; Ehrig-Eggert, Carl; Mazen, Amawi; Neubauer, E. (1996). نصوص ودراسات من مصادر صينية حول البلدان الاسلامية. Frankfurt am Main: Institut für Geschichte der Arabisch-Islamischen Wissenschaften (Institute for the History of Arabic-Islamic Science at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University). ISBN 978-3-8298-2047-9.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1999). The Chan's Great Continent: China in Western Minds. W. W. Norton. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-3933-1989-7.

- Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2011). Western Civilization: a Brief History. Boston: Wadsworth, Cencage Learning. ISBN 0-4955-7147-4.

- Strachan, Edward; Bolton, Roy (2008). Russia and Europe in the Nineteenth Century. London: Sphinx Fine Art. ISBN 978-1-9072-0002-1.

- Tarn, W.W. (1966). The Greeks in Bactria and India (reprint ed.). London & New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Torday, Laszlo (1997). Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. Durham: The Durham Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-9008-3803-0.

- Tremblay, Xavier (2007). "The Spread of Buddhism in Serindia: Buddhism Among Iranians, Tocharians and Turks before the 13th Century". In Heirman, Ann; Bumbacker, Stephan Peter (eds.). The Spread of Buddhism. Leiden & Boston: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 978-9-0041-5830-6.

- Turnbull, Stephen (19 February 2013). The Mongol Invasions of Japan 1274 and 1281. Osprey. ISBN 978-1-4728-0045-9.

- Vogel, Hans Ulrich (2013). Marco Polo Was in China: New Evidence from Currencies, Salts and Revenues. Leiden; Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9-0042-3193-1.

- Wills, John E. Jr. (1998). "Relations with Maritime Europeans, 1514–1662". In Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis (eds.). The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 8, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 2 (Hardback ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 333–375. ISBN 0-5212-4333-5.

- Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-5202-4340-8.

- Xu, Shiduan (1998). "Oghul Qaimish, Empress of Mongol Emperor Dingzong". In Lee, Lily Xiao Hong; Wiles, Sue (eds.). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Tang through Ming: 618–1644. Translated by Burns, Janine. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7656-4314-8.

- Yang, Juping (2014). "Hellenistic Information in China". CHS Research Bulletin. 2 (2).

- Yarshater, Ehsan, ed. (2003). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ye, Yiliang (2010). "Introductory Essay: Outline of the Political Relations between Iran and China". In Kauz, Ralph (ed.). Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road: From the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea. Weisbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-4470-6103-2.

- Young, Gary K. (2001). Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC - AD 305. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-4152-4219-3.

- Yu, Huan (September 2004). Hill, John E. (ed.). "The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265, Quoted in zhuan 30 of the Sanguozhi, Published in 429 CE". Depts.washington.edu. Translated by Hill, John E. Archived from the original on 15 March 2005. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- Yu, Taishan (June 2010). The Earliest Tocharians in China. in Sino-Platonic Papers

- Yü, Ying-shih (1986). "Han Foreign Relations". In Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge History of China. Vol. I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 377–388, 391. ISBN 978-0-5212-4327-8.

- Yule, Henry; Cordier, Henri, eds. (1913) [1866]. Cathay and the Way Thither, Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China. Translated by Yule, Henry. London: Hakluyt Society. ISBN 978-8-1206-1966-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Feng, Zhao (2004). "Wall hanging with centaur and warrior". In Watt, James C.Y.; O'Neill, John P.; et al. (eds.). China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 A.D. Translated by Chen, Ching-Jung; et al. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-5883-9126-1.

KSF

KSF