Evens

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2011) |

эвэсэл · эвены | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| c. 20,017 [1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 19,913[1] | |

| 104[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Russian, Even, Sakha | |

| Religion | |

| Shamanism, Russian Orthodoxy | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Evenks | |

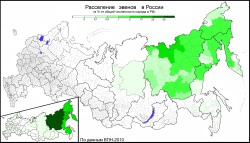

The Evens /əˈvɛn/ (Even: эвэн; pl. эвэсэл, evesel in Even and эвены, eveny in Russian; formerly called Lamuts) are a people in Siberia and the Russian Far East. They live in regions of the Magadan Oblast and Kamchatka Krai and northern parts of Sakha east of the Lena River, although they are a nomadic people. According to the 2002 census, there were 19,071 Evens in Russia. According to the 2010 census, there were 22,383 Evens in Russia. They speak their own language called Even, one of the Tungusic languages; it is heavily influenced by their lifestyle and reindeer herding. It is also closely related to the language of their neighbors, the Evenks. The Evens are close to the Evenks by their origins and culture, having migrated with them from central China over 10,000 years ago. Officially, they have been considered to be of Orthodox faith since the 19th century, though the Evens have retained some pre-Christian practices, such as shamanism. Traditional Even life is centered upon nomadic pastoralism of domesticated reindeer, supplemented with hunting, fishing and animal-trapping. Outside of Russia, there are 104 Evens in Ukraine, 19 of whom spoke Even. (Ukr. Cen. 2001)

Origins

[edit]Migration

[edit]The Evens people are part of the Eastern Siberians that migrated out of central China around 10,000 years ago. They are located in extreme northeast Siberia, and they are somewhat isolated from the rest of the indigenous groups in Siberia, with the closest groups being the Yakuts and the Evenks who are over 1,000 kilometers away.[3]

Name and Language

[edit]Before the beginning of the Soviet reign the Evens were referred to as the Lamut by other groups, originally coined by the Yakut people, a nearby Siberian indigenous group. The word Lamu refers to the Okhotsk Sea in the languages spoken in eastern Siberia, thus it is reasonable to assume that this is where the name Lamut originates. The name Even came from the Evens people themselves.[4] The Evens had yet to distinguish themselves as a separate group from the Evenk even up until the 1800s. As such, Evenk culture and language heavily influenced that of the Evens. However, there are some key differences in language that made the two separate. In the Even language the last vowel and consonant of each word is dropped, while in the Evenk language the last vowel and consonant are spoken.[4]

Etymology and Vocabulary

[edit]The Even language has a multitude of words relating to their nomadic lifestyle and reindeer herding, and a good portion of words in the Even language have to do with actions relating to these things. For example, "oralchid'ak", "nulgän", "nulgänmäj", and "nulgädäj", are their words for the concept of a nomadic lifestyle and moving from one place to another. All of these words come from the word "nulgä", which can be a measure of distance - in this case the distance one can travel in a single night - or it can also describe a group of reindeer herders. There are fourteen words in the Even language that describe very similar actions and people relating to herding and grazing, including daytime grazing and herdsmen, as well as reindeer drivers; reindeer are economically and culturally crucial to the Evens people.[5]

History

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

In the 17th century, the people today known as the Eveni were divided into three main tribes: the Okhotsk reindeer Tungus (Lamut), the Tiugesir, Memel' and Buiaksir clans as well as a sedentary group of Arman' speakers. Today, they are all known as Eveni.[6]

Housing

[edit]The traditional lodgings of the Evens were conical tents which were covered with animal skins. In the southern coastal areas, fish skins were used.[7] Settled Evens used a type of earth and log dugout.[7] Sheds were erected near the dwellings in order to house stocks of frozen fish and meat. Their economy was supplemented by winter hunts to obtain wild game. Hunters sometimes rode reindeer, and sometimes moved along on wooden skis.

Soviet Era

[edit]During the Soviet reign the government collectivized reindeer herding, which drastically changed the lives of the Evens and other indigenous groups in Siberia. With the rise of Communism after 1917, the new government aimed to "civilize" the nomadic tribes of Siberia by constructing permanent housing, and by standardizing and collectivizing reindeer herding, their main occupation and lifestyle. The Soviet government seized and redistributed the reindeer of the Evens people and forced the Evens people to use specific migration routes and dates. The Soviets created a written language in the 1930s. Many nomadic Evens were forced to settle down, join the kolkhozes, and engage in cattle-breeding and agriculture.[8]

Economy

[edit]The economy of the Evens people, both historically and now, is largely based around reindeer herding and migration, as well as hunting. The Evens kept smaller herds of reindeer than other indigenous groups in eastern Siberia, such as the Chukchi, Koryak, and the Yakut; these other groups used reindeer as food sources and trade goods, while the Evens mainly used them as a mode of transportation. Reindeer herding in this area is believed to have begun around the start of the Common Era by the ancestors of the Evens. Around this time, the ancient Tungus people had come into contact with the Mongols and Turks who introduced them to horses and horse breeding culture. The Tungus experimented with riding horses, but this failed because of the harsh climate of the Tundra. However, the saddles that they used for the horses also worked on reindeer, and a new method of transportation was born. While large scale reindeer breeding was commonplace in other parts of Siberia, it did not become a common practice where the Evens live in the north and east of Siberia until the 1600s-1700's, with the Evens not practicing it until the late 1800s into the 1900s. Because the Evens did not raise reindeer specifically for their skins and meat, they relied mostly on hunting small game such as reindeer they had not domesticated and other animals in the Tundra.[9]

Post Contact Economy

[edit]Hunting animals for their fur, squirrel in particular, became a large source of income after the indigenous groups of Siberia came into contact with the Russians. The fur trade was extremely lucrative, and as such reindeer herding became less important to the economy of the Evens than it had been previously, however it is still the primary venture of the mainland Evens. While the Evens that lived further inland focused more on herding and the fur trade, the Evens that lived on Okhotsk Sea relied heavily on fishing in order to sustain themselves.[9]

Culture

[edit]The traditional clothing worn by the Evens people consists of a coat with an apron, as well as pants and boots; both genders wear the same type of clothing. Their clothing is usually made using reindeer hides and skins, as well as moose hair. Evens are known to be very enthusiastic about smoking, and as such, most Evens also wear a pouch on their coat to keep a pipe and tobacco in. The Evens' housing and clothes are unique from the indigenous groups around them, with the Evens wearing open coats and aprons, as well as living in somewhat small conical tents called churns, while indigenous groups such as the Chukchi and the Koryak lived in a type of larger circular tent called a chorama-diu. These tents were usually made out of reindeer hides, although the Evens that lived by the sea used fish skins in addition to the hides. Since the Evens were and still are largely a nomadic people, everyone in the group shared with one another, and people were forbidden from hoarding meat from hunts, even if they were the one that had killed the game or were in the family of the hunter; this principle is called nimat. This principle also sometimes applied to smaller game such as birds and fish. Another aspect of nimat was that whenever two hunters were hunting together for animals who had pelts, the one who killed the animal got the meat and the other hunter received the skin of the animal. Even culture also includes folklore, which consists of stories and songs that usually feature ground animals, birds, and cliché ideas or stereotypes of people.[4]

Notable Evens

[edit]- Varvara Belolyubskaya, linguist and poet

- Viktor Lebedev, freestyle wrestler

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Оценка численности постоянного населения по субъектам Российской Федерации". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ a b "About number and composition population of Ukraine by data All-Ukrainian census of the population 2001". Ukraine Census 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 17 December 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ Wong, Emily H. M.; Khrunin, Andrey; Nichols, Larissa; Pushkarev, Dmitry; Khokhrin, Denis; Verbenko, Dmitry; Evgrafov, Oleg; Knowles, James; Novembre, John; Limborska, Svetlana; Valouev, Anton (January 2017). "Reconstructing genetic history of Siberian and Northeastern European populations". Genome Research. 27 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1101/gr.202945.115. ISSN 1549-5469. PMC 5204334. PMID 27965293.

- ^ a b c Fitzhugh, William W.; Crowell. "Crossroads of continents". library.si.edu. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krivoshapkina and Prokopieva, Ekaterina and Svetlana (August 18, 2016). "Ethno-Cultural Concept 'Reindeer Breeding' in the Even Language" (PDF). Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities. 8 (3): 16–17. doi:10.21659/rupkatha.v8n3.03.

- ^ B. O. Dolgikh and Chester S. Chard (trans.), "The Formation of the Modern Peoples of the Soviet North" Arctic Anthropology 9(1) (1972): 17-26

- ^ a b Crossroads of continents : cultures of Siberia and Alaska. Smithsonian Libraries. Washington, D.C. : Smithsonian Institution Press. 1988. ISBN 978-0-87474-442-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Vitebsky, Piers (February 11, 2006). "Life Among 'The Reindeer People'". NPR. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Fitzhugh, William W.; Crowell. "Crossroads of continents". library.si.edu. Retrieved 2023-11-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

[edit]- James Forsyth, "A History of the Peoples of Siberia",1992

- Vitebsky, Piers (2005). Reindeer People: Living with Animals and Spirits in Siberia. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-713362-6.

KSF

KSF