Factions in the Republican Party (United States)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 40 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 40 min

The Republican Party in the United States includes several factions, or wings. During the 19th century, Republican factions included the Half-Breeds, who supported civil service reform; the Radical Republicans, who advocated the immediate and total abolition of slavery, and later advocated civil rights for freed slaves during the Reconstruction era; and the Stalwarts, who supported machine politics.

In the 20th century, Republican factions included the Progressive Republicans, the Reagan coalition, and the liberal Rockefeller Republicans.

In the 21st century, Republican factions include conservatives (represented in the House by the Republican Study Committee and the Freedom Caucus), moderates (represented in the House by the Republican Governance Group, Republican Main Street Caucus, and the Republican members of the Problem Solvers Caucus), and libertarians (represented in Congress by the Republican Liberty Caucus). During the first presidency of Donald Trump, Trumpist and anti-Trumpist factions arose within the Republican Party.

21st century factions

[edit]

During the presidency of Barack Obama, the Republican Party experienced internal conflict between its governing class (known as the Republican establishment) and the anti-establishment, small-government Tea Party movement.[4][5][6][7] In 2019, during the presidency of Donald Trump, Perry Bacon Jr. of FiveThirtyEight.com asserted that there were five groups of Republicans: Trumpists, Pro-Trumpers, Trump-Skeptical Conservatives, Trump-Skeptical Moderates, and Anti-Trumpers.[8]

In February 2021, following Trump's 2020 loss to Democrat Joe Biden and the 2021 United States Capitol attack, Philip Bump of The Washington Post posited that the Republican Party in the U.S. House of Representatives consisted of three factions: the Trumpists (who voted against the second impeachment of Donald Trump in 2021, voted against stripping Marjorie Taylor Greene of her committee assignments, and supported efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election), the accountability caucus (who supported either the Trump impeachment, the effort to discipline Greene, or both), and the pro-democracy Republicans (who opposed the Trump impeachment and the effort to discipline Greene but also opposed efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election results).[9] Also in February 2021, Carl Leubsdorf of the Dallas Morning News asserted that there were three groups of Republicans: Never Trumpers (including Bill Kristol, Sen. Mitt Romney, and governors Charlie Baker and Larry Hogan), Sometimes Trumpers (including Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and former U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley), and Always Trumpers (including Sens. Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley).[10]

In March 2021, one survey indicated that five factions of Republican voters had emerged following Trump's presidency: Never Trump, Post-Trump G.O.P. (voters who liked Trump but did not want him to run for president again), Trump Boosters (voters who approved of Trump, but identified more closely with the Republican Party than with Trump), Die-hard Trumpers, and Infowars G.O.P. (voters who subscribe to conspiracy theories).[11] In November 2021, Pew Research Center identified four Republican-aligned groups of Americans: Faith and Flag Conservatives, Committed Conservatives, the Populist Right, and the Ambivalent Right.[12]

As of 2023, congressional Republicans refer to the various House Republican factions as the Five Families.[13][14][15][16] Derived from The Godfather, the term refers to Mafia crime families.[14] The Five Families consist of "the right-wing House Freedom Caucus, the conservative Republican Study Committee, the business-minded Main Street Caucus, the mainstream Republican Governance Group", and the Republican members of the bipartisan Problem Solvers Caucus. The House Republican factions overlap with one another, and some members belong to no caucus.[15]

Conservatives

[edit]

The conservative wing grew out of the 1950s and 1960s, with its initial leaders being Senator Robert A. Taft, Russell Kirk, and William F. Buckley Jr. Its central tenets include the promotion of individual liberty and free-market economics and opposition to labor unions, high taxes, and government regulation.[17] The Republican Party has undergone a major decrease in the influence of its establishment conservative faction since the election of Donald Trump in 2016.[18][19][20]

In economic policy, conservatives call for a large reduction in government spending, less regulation of the economy, and privatization or changes to Social Security. Supporters of supply-side economics and fiscal conservatives predominate, but there are deficit hawks and protectionists within the party as well. Before 1930, the Northeastern industrialist faction of the GOP was strongly committed to high tariffs, a political stance that returned to popularity in many conservative circles during the Trump presidency.[21][22] The conservative wing typically supports socially conservative positions, such as supporting gun rights and restrictions on abortion, though there is a wide range of views on such issues within the party.[23]

Conservatives generally oppose affirmative action, support increased military spending, and are opposed to gun control. On the issue of school vouchers, conservative Republicans split between supporters who believe that "big government education" is a failure and opponents who fear greater government control over private and church schools. Parts of the conservative wing have been criticized for being anti-environmentalist[25][26][27] and promoting climate change denial[28][29][30] in opposition to the general scientific consensus, making them unique even among other worldwide conservative parties.[30]

Long-term shifts in conservative thinking following the election of Trump have been described as a "new fusionism" of traditional conservative ideology and right-wing populist themes.[31] These have resulted in shifts towards greater support of national conservatism,[32] protectionism,[33] cultural conservatism, a more realist foreign policy, skepticism of neoconservatism, reduced efforts to roll back entitlement programs, and a disdain for traditional checks and balances.[31][34]

Neoconservatives

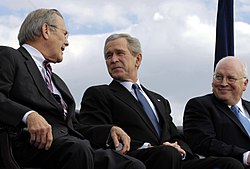

[edit]Neoconservatives promote an interventionist foreign policy and democracy or American interests abroad. Neoconservatives have been credited with importing into the Republican Party a more active international policy. They are amenable to unilateral military action when they believe it serves a morally valid purpose (such as the spread of democracy or deterrence of human rights abuses abroad). They grounded in a realist philosophy of "peace through strength."[35][36][37][38] Many of its adherents became politically famous during the Republican presidential administrations of the late 20th century, and neoconservatism peaked in influence during the administration of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney during the 2000s, when they played a major role in promoting and planning the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[39]

Prominent neoconservatives in the Bush-Cheney administration included John Bolton, Paul Wolfowitz, Elliott Abrams, Richard Perle, and Paul Bremer. During and after Donald Trump's presidency, neoconservatism has declined and non-interventionism and right-wing populism has grown among elected federal Republican officeholders.[40][41] However, after Trump took office, some neoconservatives joined his administration, such as John Bolton, Mike Pompeo, Elliott Abrams[42] and Nadia Schadlow.

Neoconservatives' role remains key in foreign policy issues. The Hudson Institute has been described as neoconservative,[43][44] whose researchers and foreign policy experts have played a key role in Republican administrations since the 2000s. Other organizations associated with this faction include the American Enterprise Institute,[45] the Foundation for Defense of Democracies,[46][47][48] the Henry Jackson Society[49] and the Project for the New American Century.[50]

Christian right

[edit]

The Christian right is a conservative Christian political faction characterized by strong support of socially conservative and Christian nationalist policies.[51][52][53] Christian conservatives seek to use the teachings of Christianity to influence law and public policy.[54]

In the United States, the Christian right is an informal coalition formed around a core of evangelical Protestants and conservative Roman Catholics, as well as a large number of Latter-day Saints (Mormons).[55][56][57][58] The movement has its roots in American politics going back as far as the 1940s and has been especially influential since the 1970s.[59] In the late 20th century, the Christian right became strongly connected to the Republican Party.[60] Republican politicians associated with the Christian right in the 21st century include Tennessee Senator Marsha Blackburn, former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee, and former Senator Rick Santorum.[61] Many within the Christian right have also identified as social conservatives, which sociologist Harry F. Dahms has described as Christian doctrinal conservatives (anti-abortion, anti-LGBT rights) and gun-rights conservatives (pro-NRA) as the two domains of ideology within social conservatism.[62] Christian nationalists generally seek to declare the U.S. a Christian nation, enforce Christian values, and overturn the separation of church and state.[52][53]

Libertarians

[edit]

Libertarians make up a relatively small faction of the Republican Party.[63][64] In the 1950s and 60s, fusionism—the combination of traditionalist and social conservatism with political and economic right-libertarianism—was essential to the movement's growth.[65] This philosophy is most closely associated with Frank Meyer.[66] Barry Goldwater also had a substantial impact on the conservative-libertarian movement of the 1960s.[67]

Libertarian conservatives in the 21st century favor cutting taxes and regulations, repealing the Affordable Care Act, and protecting gun rights.[68] On social issues, they favor privacy, oppose the USA Patriot Act, and oppose the war on drugs.[68] On foreign policy, libertarian conservatives favor non-interventionism.[69][70] The Republican Liberty Caucus, which describes itself as "the oldest continuously operating organization in the Liberty Republican movement with state charters nationwide", was founded in 1991.[71] The House Liberty Caucus is a congressional caucus formed by former Representative Justin Amash, a former Republican of Michigan who joined the Libertarian Party in 2020 before returning in 2024.[72]

Prominent libertarian conservatives within the Republican Party include New Hampshire Governor Chris Sununu,[73][74] Senators Mike Lee and Rand Paul, Representative Thomas Massie, former Representative and Governor of South Carolina Mark Sanford,[75] and former Representative Ron Paul[76] (who was a Republican prior to 1987 and again from 1996 to 2015, and a Libertarian from 1987 to 1996 and since 2015). Ron Paul ran for president once as a Libertarian and twice more recently as a Republican.

The libertarian conservative wing of the party had significant cross-over with the Tea Party movement.[77][78]

During the 2024 United States elections, the Republican Party adopted pro-cryptocurrency policies, which were originally advocated by the libertarian wing of the party.[79] As the Republican presidential nominee, Donald Trump addressed the 2024 Libertarian National Convention, pledging support for cryptocurrency, opposing central bank digital currency and expressing support for the commutation of Ross Ulbricht. Trump's 2024 campaign featured greater influence from technolibertarian elements, particularly Elon Musk, who was subsequently nominated to lead the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE).[80][81][82] 2024 Republican presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy, who was chosen to lead DOGE alongside Musk, has called for a synthesis between nationalism and libertarianism within the Republican Party, while opposing protectionist elements.[83][84] Musk and Ramaswamy have clashed with elements within the right-wing populist faction over high-skilled legal immigration to the United States.[85][86]

Moderates

[edit]

Moderate Republicans tend to be conservative-to-moderate on fiscal issues and moderate-to-liberal on social issues, and usually represent swing states or blue states. Moderate Republican voters are typically highly educated,[87] affluent, socially moderate or liberal and often part of the Never Trump movement.[88] Ideologically, such Republicans resemble the conservative liberals of Europe.[89]

While they sometimes share the economic views of other Republicans (i.e. lower taxes, deregulation, and welfare reform), moderate Republicans differ in that some support affirmative action,[90] LGBT rights and same-sex marriage, legal access to and even public funding for abortion, gun control laws, more environmental regulation and action on climate change, fewer restrictions on immigration and a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants, and embryonic stem cell research.[91][92] In the 21st century, some former Republican moderates have switched to the Democratic Party.[93][94][95]

Prominent 21st century moderate Republicans include Senators John McCain of Arizona, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Susan Collins of Maine[96][97][98][99] and several current or former governors of northeastern states, such as Charlie Baker of Massachusetts[100] and Phil Scott of Vermont.[101] Another moderate Republican is incumbent governor of Nevada Joe Lombardo, who was previously the Sheriff of Clark County.[102] Moderate Republican Representatives include Brian Fitzpatrick,[103] Mike Lawler,[104] and David Valadao.[105]

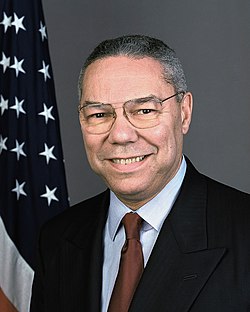

One of the most high-ranking moderate Republicans in recent history was Colin Powell as Secretary of State in the first term of the George W. Bush administration (Powell left the Republican Party in January 2021 following the 2021 storming of the United States Capitol, and had endorsed every Democrat for president in the general election since 2008).[106]

The Republican Governance Group is a caucus of moderate Republicans within the House of Representatives.[14]

Trumpists

[edit]

Sometimes referred to as the MAGA or "America First" movement,[107][108] Trumpists are the dominant faction in the Republican Party as of 2024.[109][18][110][20][111] It has been described as consisting of a range of right-wing ideologies including but not limited to right-wing populism,[112][113][114] national conservatism,[115] neo-nationalism,[116] and Trumpism, the political movement associated with Donald Trump and his base.[117][118] They have been described by some commentators, including Joseph Lowndes, James A. Gardner, and Guy-Uriel Charles, as the American political variant of the far-right.[119][120][121]

Rachel Kleinfeld, senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, characterizes Trumpism as an authoritarian, antidemocratic movement which has successfully weaponized cultural issues, and that cultivates a narrative placing white people, Christians, and men at the top of a status hierarchy as its response to the so-called "Great Replacement" theory, a claim that minorities, immigrants, and women, enabled by Democrats, Jews, and elites, are displacing white people, Christians, and men from their "rightful" positions in American society.[122] In international relations, Trumpists support U.S. aid to Israel but not to Ukraine,[123][124] are generally supportive towards Russia,[125][126][127] yet claim to favor an isolationist "America First" foreign policy agenda.[128][129][130][131] They generally reject compromise within the party and with Democrats,[132][133] and are willing to oust fellow Republican office holders they deem to be too moderate.[134][135] Compared to other Republicans, the Trumpist faction is more likely to be immigration restrictionists,[136] and to be against free trade,[137] neoconservatism,[138] and environmental protection laws.[139]

The Republican Party's Trumpist and far-right movements emerged in occurrence with a global increase in such movements in the 2010s and 2020s,[140][141] coupled with entrenchment and increased partisanship within the party since 2010, fueled by the rise of the Tea Party movement which has also been described as far-right.[142] The election of Trump in 2016 split the party into pro-Trump and anti-Trump factions.[143][144]

When conservative columnist George Will advised voters of all ideologies to vote for Democratic candidates in the Senate and House elections of November 2018,[145] political writer Dan McLaughlin at the National Review responded that doing so would make the Trumpist faction even more powerful within the Republican party.[146] Anticipating Trump's defeat in the U.S. presidential election held on November 3, 2020, Peter Feaver wrote in Foreign Policy magazine: "With victory having been so close, the Trumpist faction in the party will be empowered and in no mood to compromise or reform."[147] A poll conducted in February 2021 indicated that a plurality of Republicans (46% versus 27%) would leave the Republican Party to join a new party if Trump chose to create it.[148] Nick Beauchamp, assistant professor of political science at Northeastern University, says he sees the country as divided into four parties, with two factions representing each of the Democratic and Republican parties: "For the GOP, there's the Trump faction—which is the larger group—and the non-Trump faction".[149]

Lilliana Mason, associate professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University, states that Donald Trump solidified the trend among Southern white conservative Democrats since the 1960s of leaving the Democratic Party and joining the Republican Party: "Trump basically worked as a lightning rod to finalize that process of creating the Republican Party as a single entity for defending the high status of white, Christian, rural Americans. It's not a huge percentage of Americans that holds these beliefs, and it's not even the entire Republican Party; it's just about half of it. But the party itself is controlled by this intolerant, very strongly pro-Trump faction."[150]

Julia Azari, an associate professor of political science at Marquette University, noted that not all Trumpist Republicans are public supporters of Donald Trump, and that some Republicans endorse Trump policies while distancing themselves from Trump as a person.[151]

In a speech he gave on November 2, 2022, at Washington's Union Station near the U.S. Capitol, President Biden asserted that "the pro-Trump faction" of the Republican Party is trying to undermine the U.S. electoral system and suppress voting rights.[152][153]

Anti-Trump faction

[edit]

A divide has formed in the party between those who remain loyal to Donald Trump and those who oppose him.[154] A recent survey concluded that the Republican Party was divided between pro-Trump (the "Trump Boosters," "Die-hard Trumpers," and "Infowars G.O.P." wings) and anti-Trump factions (the "Never Trump" and "Post-Trump G.O.P." wings).[11] Senator John McCain was an early leading critic of Trumpism within the Republican Party, refusing to support the then-Republican presidential nominee in the 2016 presidential election.[155]

Several critics of the Trump faction have faced various forms of retaliation. Representative Liz Cheney was removed from her position as Republican conference chair in the House of Representatives, which was perceived as retaliation for her criticism of Trump;[156] in 2022, she was defeated by a pro-Trump primary challenger.[157] Representative Adam Kinzinger decided to retire at the end of his term, while Murkowski faced a pro-Trump primary challenge in 2022 against Kelly Tshibaka whom she defeated.[158][159] A primary challenge to Romney had been suggested[160] by Jason Chaffetz, who has criticized his opponents within the Republican Party as "Trump haters".[161] Romney chose not to run for re-election in 2024.[162]

Representative Anthony Gonzalez, one of 10 House Republicans who voted to impeach Trump over the Capitol riot, called him "a cancer" while announcing his retirement.[163] Former Governor of New Jersey Chris Christie, who was running against Trump in the 2024 Republican primaries, called him "a lonely, self-consumed, self-serving, mirror hog" in his presidential announcement.[164] Indiana senator Todd Young is one of few elected Republican senators that did not support Trump's 2024 campaign.[165]

Organizations associated with this faction include The Lincoln Project,[166] Republican Accountability Project[167] and Republicans for the Rule of Law.[168]

Political caucuses

[edit]| Caucus | Problem Solvers Caucus | Republican Governance Group | Republican Main Street Caucus | Republican Study Committee | Freedom Caucus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political position | Center[169] | Center[170] to center-right[171] | Center[172] to center-right[173][174] | Center-right[175][verification needed] to right-wing[176] | Right-wing[177] to far-right[178] |

| 2020 | 28 / 213

|

45 / 213

|

0 / 213

|

157 / 213

|

45 / 213

|

| 2022[179] | 29 / 222

|

42 / 222

|

67 / 222

|

173 / 222

|

33 / 222

|

Historical factions

[edit]Stalwarts

[edit]The Stalwarts were a traditionalist faction that existed from the 1860s through the 1880s. They represented "traditional" Republicans who favored machine politics and opposed the civil service reforms of Rutherford B. Hayes and the more progressive Half-Breeds.[182] They declined following the elections of Hayes and James A. Garfield. After Garfield's assassination by Charles J. Guiteau, his Stalwart Vice President Chester A. Arthur assumed the presidency. However, rather than pursuing Stalwart goals he took up the reformist cause, which curbed the faction's influence.[183]

Half-Breeds

[edit]The Half-Breeds were a reformist faction of the 1870s and 1880s. The name, which originated with rivals claiming they were only "half" Republicans, came to encompass a wide array of figures who did not all get along with each other. Generally speaking, politicians labeled Half-Breeds were moderates or progressives who opposed the machine politics of the Stalwarts and advanced civil service reforms.[183]

Radical Republicans

[edit]

The Radical Republicans were a major factor of the party from its inception in 1854 until the end of the Reconstruction Era in 1877. The Radicals strongly opposed slavery, were hard-line abolitionists, and later advocated equal rights for the freedmen and women. They were often at odds with the moderate and conservative factions of the party. During the American Civil War, Radical Republicans pressed for abolition as a major war aim and they opposed the moderate Reconstruction plans of Abraham Lincoln as too lenient on the Confederates. After the war's end and Lincoln's assassination, the Radicals clashed with Andrew Johnson over Reconstruction policy.[184]

After winning major victories in the 1866 congressional elections, the Radicals took over Reconstruction, pushing through new legislation protecting the civil rights of African Americans. John C. Frémont of Michigan, the party's first nominee for president in 1856, was a Radical Republican. Upset with Lincoln's politics, the faction split from the Republican Party to form the short-lived Radical Democratic Party in 1864 and again nominated Frémont for president. They supported Ulysses S. Grant for president in 1868 and 1872, who worked closely with them to protect African Americans during Reconstruction. As Southern Democrats retook control in the South and enthusiasm for continued Reconstruction declined in the North, their influence within the GOP waned.[184]

Progressive Republicans

[edit]

Historically, the Republican Party included a progressive wing that advocated using government to improve the problems of modern society. Theodore Roosevelt, an early leader of the progressive movement, advanced a "Square Deal" domestic program as president (1901–09) that was built on the goals of controlling corporations, protecting consumers, and conserving natural resources.[185] After splitting with his successor, William Howard Taft, in the aftermath of the Pinchot–Ballinger controversy,[186] Roosevelt sought to block Taft's re-election, first by challenging him for the 1912 Republican presidential nomination, and then when that failed, by entering the 1912 presidential contest as a third party candidate, running on the Progressive ticket. He succeeded in depriving Taft of a second term, but came in second behind Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

After Roosevelt's 1912 defeat, the progressive wing of the party went into decline. Progressive Republicans in the U.S. House of Representatives held a "last stand" protest in December 1923, at the start of the 68th Congress, when they refused to support the Republican Conference nominee for Speaker of the House, Frederick H. Gillett, voting instead for two other candidates. After eight ballots spanning two days, they agreed to support Gillett in exchange for a seat on the House Rules Committee and pledges that subsequent rules changes would be considered. On the ninth ballot, Gillett received 215 votes, a majority of the 414 votes cast, to win the election.[187]

In addition to Theodore Roosevelt, leading early progressive Republicans included Robert M. La Follette, Charles Evans Hughes, Hiram Johnson, William Borah, George W. Norris, William Allen White, Victor Murdock, Clyde M. Reed and Fiorello La Guardia.[188]

Old Guard

[edit]The Old Guard was the conservative faction of the Republican Party between 1945 and 1964. They coalesced around their opposition to the shifts in traditional economic and foreign policy under the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt. This opposition most noticeably directed to the New Deal, which was variously derided by Old Guard lawmakers as communist, socialist, or overreaching, seeing its programs as unwanted, unconstitutional, unwise, and politically unprofitable.[189]

To counter the New Deal, Republicans of the Old Guard espoused Americanism, which entailed a strict construction of the Constitution, fiscal responsibility, and state and local over federal regulation. Politically, they opposed federal regulation of state, local, or business interests. They viewed “big government” as a threat to liberty, which they interpreted as economic freedom, which they saw as critical to incentivizing individuals to improve their material welfare and develop the pioneer virtues of individualism and self-reliance. The Old Guard also espoused a unilateralist foreign policy, eschewing alliances that entailed advance military commitments while “go[ing] it alone” in foreign engagements. This also entailed economic self-sufficiency, prioritizing American financial interests, and thus partially informed the Old Guard’s support for tariffs on imports and opposition to foreign aid.[189]

While sharing the above overarching goals, figures affiliated with this movement varied in their policy stances. These included Bruce Fairchild Barton, John W. Bricker, Styles Bridges, Joseph McCarthy, Everett Dirksen,[190] Walter Judd,[191] and Robert A. Taft.

Birchers

[edit]This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (June 2024) |

In the 1964 Republican primaries, the John Birch Society (JBS) helped to secure Barry Goldwater’s Republican presidential nomination, defeating Nelson Rockefeller. Original members believed the Republican party was in danger of becoming too moderate.[192] Members of the John Birch Society, known as Birchers, were associated with the radical right, anti-communism, and ultraconservatism.[193][page needed] The John Birch Society was founded in 1958 by businessman Robert W. Welch Jr., and is controversial for its promotion of conspiracy theories.[194]

Rockefeller Republicans

[edit]

Moderate or liberal Republicans in the 20th century, particularly those from the Northeast and West Coast, were referred to as "The Eastern Establishment" or "Rockefeller Republicans", after Nelson Rockefeller, Vice President during the Gerald Ford administration.[195][196][197]

With their power decreasing in the final decades of the 20th century, many Rockefeller-style Republicans were replaced by conservative and moderate Democrats, such as those from the Blue Dog or New Democrat coalitions. Massachusetts Republican Elliot Richardson (who served in several cabinet positions during the Richard Nixon administration) and writer and academic Michael Lind argued that the liberalism of Democratic President Bill Clinton and the rest of the New Democrat movement were in many ways to the right of Dwight Eisenhower, Rockefeller, and John Lindsay, Republican Congressman and Mayor of New York City in the late 1960s.[198][199]

Reagan coalition

[edit]

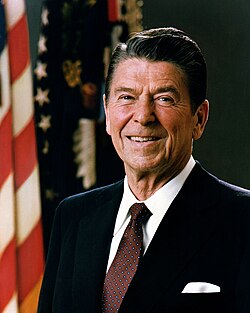

According to historian George H. Nash, the Reagan coalition in the Republican Party, which centered around Ronald Reagan and his administration throughout all of the 1980s (continuing in the late 1980s with the George H. W. Bush administration), originally consisted of five factions: the libertarians, the traditionalists, the anti-communists, the neoconservatives, and the religious right (which consisted of Protestants, Catholics, and some Jewish Republicans).[17][200]

Tea Party movement

[edit]

The Tea Party movement was an American fiscally conservative political movement within the Republican Party that began in 2009 following the election of Barack Obama as President of the United States.[201][202] Members of the movement have called for lower taxes, and for a reduction of the national debt of the United States and federal budget deficit through decreased government spending.[203][204] The movement supports small-government principles[205][206] and opposes government-sponsored universal healthcare.[207] It has been described as a popular constitutional movement.[208]

On matters of foreign policy, the movement largely supports avoiding being drawn into unnecessary conflicts and opposes "liberal internationalism".[209] Its name refers to the Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773, a watershed event in the launch of the American Revolution.[210] By 2016, Politico said that the modern Tea Party movement was "pretty much dead now"; however, the article noted that it seemed to die in part because some of its ideas had been "co-opted" by the mainstream Republican Party.[211]

Politicians associated with the Tea Party include former Representatives Ron Paul, Michele Bachmann and Allen West,[212][213] Senators Ted Cruz, Mike Lee, Rand Paul and Tim Scott,[214][215][216] former Senator Jim DeMint,[215] former acting White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney,[217] and 2008 Republican vice presidential nominee and former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin.[213] Although there has never been any one clear founder or leader of the movement, Palin scored highest in a 2010 Washington Post poll asking Tea Party organizers "which national figure best represents your groups?".[218] Ron Paul was described in a 2011 Atlantic article as its "intellectual godfather".[219] Both Paul and Palin, although ideologically different in many ways, had a major influence on the emergence of the movement due to their separate 2008 presidential primary and vice presidential general election runs respectively.[220][209]

Several political organizations were created in response to the movement's growing popularity in the late 2000s and into the early 2010s, including the Tea Party Patriots, Tea Party Express and Tea Party Caucus.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Antonova, Katherine (July 25, 2017). The GOP Is No Longer A 'Conservative' Party. HuffPost. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ Hogan, Fuzz (May 6, 2023). 'Nationalism' redefines the American right. CNN. Retrieved November 17, 2024.

- ^ "Trump: 'I'm a nationalist'". Politico. October 22, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ "Republicans and Tea Party Activists in 'Full Scale Civil War'". ABC News. December 12, 2013.

- ^ "GOP Establishment Grapples With A Tea Party That Won't Budge". NPR.org. October 2, 2013. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015.

- ^ Abramowitz, Alan (November 14, 2013). "Not Their Cup of Tea: The Republican Establishment versus the Tea Party". CenterForPolitics.org. Archived from the original on November 16, 2013.

- ^ "Establishment Vs. Tea Party in Primary Showdowns". www.cbsnews.com. September 14, 2010. Archived from the original on January 17, 2022.

- ^ Bacon, Perry (March 27, 2019). "The Five Wings Of The Republican Party". FiveThirtyEight.

- ^ Bump, Philip (February 5, 2021). "The Three Factions of House Republicans". The Washington Post.

- ^ "The GOP is divided into 3 warring factions focused on Trump: Never, Sometimes and Always". Dallas News. February 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Haberman, Maggie (March 12, 2021). "A survey of Republicans shows 5 factions have emerged after Trump's presidency". The New York Times.

- ^ "The Republican Coalition among the U.S. electorate". PewResearch.org. November 9, 2021.

- ^ Blanco, Adrian; Sotomayor, Marianna; Dormido, Hannah (March 24, 2023). "Meet 'the five families' that wield power in McCarthy's House majority". washingtonpost.com.

- ^ a b c Wilkins, Emily (February 28, 2023). "McCarthy Turns to 'Five Families' to Keep Peace Among GOP Rivals".

- ^ a b Broadwater, Luke (October 23, 2023). "'5 Families' and Factions Within Factions; Why the House G.O.P. Can't Unite". The New York Times.

- ^ Raju, Manu; Zanona, Melanie (February 13, 2023). "Kevin McCarthy leans on 'five families' as House GOP plots debt-limit tactics". CNN.com.

- ^ a b Donald T. Critchlow. The Conservative Ascendancy: How the GOP Right Made Political History (2nd ed. 2011).

- ^ a b Biebricher, Thomas (October 25, 2023). "The Crisis of American Conservatism in Historical–Comparative Perspective". Politische Vierteljahresschrift. 65 (2): 233–259. doi:10.1007/s11615-023-00501-2. ISSN 2075-4698.

- ^ Aratani, Lauren (February 26, 2021). "Republicans unveil two minimum wage bills in response to Democrats' push". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

In keeping with the party's deep division between its dominant Trumpist faction and its more traditionalist party elites, the twin responses seem aimed at appealing on one hand to its corporate-friendly allies and on the other hand to its populist rightwing base. Both have an anti-immigrant element.

- ^ a b Desiderio, Andrew; Sherman, Jake; Bresnahan, John (February 7, 2024). "The end of the Old GOP". Punchbowl News. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ Aberbach, Joel D.; Peele, Gillian (2011). Crisis of Conservatism?:The Republican Party, the Conservative Movement, and American Politics After Bush. Oxford University Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780199831364. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018.

- ^ Becker, Bernie (February 13, 2016). "Trump's 6 populist positions". POLITICO. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ William Martin, With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America (1996).

- ^ Jones, Jeffrey (August 2, 2010). "Wyoming, Mississippi, Utah Rank as Most Conservative States". Gallup. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Shabecoff, Philip (2000). Earth Rising: American Environmentalism in the 21st Century. Island Press. p. 125. ISBN 9781597263351. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

republican party anti-environmental.

- ^ Hayes, Samuel P. (2000). A History of Environmental Politics Since 1945. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780822972242. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ^ Sellers, Christopher (June 7, 2017). "How Republicans came to embrace anti-environmentalism". Vox. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ^ Dunlap, Riley E.; McCright, Araon M. (August 7, 2010). "A Widening Gap: Republican and Democratic Views on Climate Change". Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 50 (5): 26–35. doi:10.3200/ENVT.50.5.26-35. S2CID 154964336.

- ^ Båtstrand, Sondre (2015). "More than Markets: A Comparative Study of Nine Conservative Parties on Climate Change". Politics and Policy. 43 (4): 538–561. doi:10.1111/polp.12122. ISSN 1747-1346.

The U.S. Republican Party is an anomaly in denying anthropogenic climate change.

- ^ a b Chait, Jonathan (September 27, 2015). "Why Are Republicans the Only Climate-Science-Denying Party in the World?". New York. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

Of all the major conservative parties in the democratic world, the Republican Party stands alone in its denial of the legitimacy of climate science. Indeed, the Republican Party stands alone in its conviction that no national or international response to climate change is needed. To the extent that the party is divided on the issue, the gap separates candidates who openly dismiss climate science as a hoax, and those who, shying away from the political risks of blatant ignorance, instead couch their stance in the alleged impossibility of international action.

- ^ a b Ashbee, Edward; Waddan, Alex (December 13, 2023). "US Republicans and the New Fusionism". The Political Quarterly. 95: 148–156. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.13341. ISSN 1467-923X.

- ^ "The growing peril of national conservatism". The Economist. February 15, 2024. Archived from the original on February 15, 2024. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ "The Republican Party no longer believes America is the essential nation". The Economist. October 26, 2023. Archived from the original on February 13, 2024. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ Garcia-Navarro, Lulu (January 21, 2024). "Inside the Heritage Foundation's Plans for 'Institutionalizing Trumpism'". The New York Times Magazine. New York City. ISSN 0028-7822. Archived from the original on February 13, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ Dagger, Richard. "Neoconservatism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on May 31, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ "Neoconservative". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Archived from the original on September 25, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ John Ehrman. The Rise of Neoconservatism: Intellectual and Foreign Affairs 1945–1994 (2005).

- ^ Justin Vaïsse. Neoconservatism: The Biography of a Movement (2010).

- ^ Record, Jeffery. Wanting War: Why the Bush Administration Invaded Iraq. Potomac Books, Inc. pp. 47–50.

- ^ Rucker, Philip; Costa, Robert (March 21, 2016). "Trump questions need for NATO, outlines noninterventionist foreign policy". The Washington Post.

- ^ Dodson, Kyle; Brooks, Clem (September 20, 2021). "All by Himself? Trump, Isolationism, and the American Electorate". The Sociological Quarterly. 63 (4): 780–803. doi:10.1080/00380253.2021.1966348. ISSN 0038-0253. S2CID 240577549.

- ^ "Elliott Abrams, prominent D.C. neocon, named special envoy for Venezuela". Politico. January 25, 2019. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- ^ "Hudson Institute". Militarist Monitor.

- ^ Danny Cooper (2011). Neoconservatism and American Foreign Policy: A Critical Analysis. Taylor & Francis. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-203-84052-8. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Matthew Christopher Rhoades (2008). Neoconservatism: Beliefs, the Bush Administration, and the Future. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-549-62046-4. Retrieved June 12, 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ John Feffer (2003). Power Trip: Unilateralism and Global Strategy After September 11. Seven Stories Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-60980-025-3. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Foster, Peter (February 24, 2013). "Obama's new head boy". The Telegraph (UK). Archived from the original on February 28, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Jonsson, Patrik (June 11, 2009). "Shooting of two soldiers in Little Rock puts focus on 'lone wolf' Islamic extremists". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on April 6, 2013. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ^ K. Dodds, K. and S. Elden, "Thinking Ahead: David Cameron, the Henry Jackson Society and BritishNeoConservatism," British Journal of Politics and International Relations (2008), 10(3): 347–63.

- ^ Matthew Christopher Rhoades (2008). Neoconservatism: Beliefs, the Bush Administration, and the Future. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-549-62046-4. Retrieved June 12, 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Whitehead, Andrew L.; Perry, Samuel L.; Baker, Joseph O. (January 25, 2018). "Make America Christian Again: Christian Nationalism and Voting for Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election". Sociology of Religion. 79 (2): 147–171. doi:10.1093/socrel/srx070.

The current study establishes that, independent of these influences, voting for Trump was, at least for many Americans, a symbolic defense of the United States' perceived Christian heritage. Data from a national probability sample of Americans surveyed soon after the 2016 election shows that greater adherence to Christian nationalist ideology was a robust predictor of voting for Trump, even after controlling for economic dissatisfaction, sexism, anti-black prejudice, anti-Muslim refugee attitudes, and anti-immigrant sentiment, as well as measures of religion, sociodemographics, and political identity more generally.

- ^ a b Smith, Peter (February 17, 2024). "Many believe the founders wanted a Christian America. Some want the government to declare one now". Associated Press. New York. Archived from the original on February 19, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Rouse, Stella; Telhami, Shibley (September 21, 2022). "Most Republicans Support Declaring the United States a Christian Nation". Politico. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Anderson, Margaret L.; Taylor, Howard Francis (2006). Sociology: Understanding a Diverse Society. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-534-61716-5.

- ^ Deckman, Melissa Marie (2004). School Board Battles: The Christian Right in Local Politics. Georgetown University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9781589010017. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

More than half of all Christian right candidates attend evangelical Protestant churches, which are more theologically liberal. A relatively large number of Christian Right candidates (24 percent) are Catholics; however, when asked to describe themselves as either "progressive/liberal" or "traditional/conservative" Catholics, 88 percent of these Christian right candidates place themselves in the traditional category.

- ^ Schweber, Howard (February 24, 2012). "The Catholicization of the American Right". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ^ Melissa Marie Deckman (2004). School Board Battles: the Christian right in Local Politics. Georgetown University Press.

- ^ "Five things you should know about Mormon politics". Religion News Service. April 27, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ "Christian Right". hirr.hartsem.edu. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ Haberman, Clyde (October 28, 2018). "Religion and Right-Wing Politics: How Evangelicals Reshaped Elections". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 29, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2019 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Cohn, Nate (May 5, 2015). "Mike Huckabee and the Continuing Influence of Evangelicals". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 6, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2019 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Smith, Robert B. (2014). "Social Conservatism, Distractors, and Authoritarianism: Axiological versus instrumental rationality". In Dahms, Harry F. (ed.). Mediations of Social Life in the 21st Century. Emerald Group Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 9781784412227.

- ^ Pew Research Center (June 26, 2014). "Beyond Red vs Blue:The Political Typology". Archived from the original on June 29, 2014.

- ^ Silver, Nate (April 9, 2015). "There are Few Libertarians But Many Americans Have Libertarian Views". Archived from the original on April 28, 2017.

- ^ Dionne Jr., E.J. (1991). Why Americans Hate Politics. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 161.

- ^ Meyer, Frank (1996). In Defense of Freedom and Other Essays. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

- ^ Poole, Robert (August–September 1998), "In memoriam: Barry Goldwater", Reason (Obituary), archived from the original on June 28, 2009

- ^ a b "A New Guide to the Republican Herd". archive.nytimes.com. August 26, 2012.

- ^ Barnett, Randy E. (July 17, 2007). "Libertarians and the War". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ^ "Toward a Libertarian Foreign Policy". Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ^ History of the RLC, Republican Liberty Caucus (accessed August 19, 2016).

- ^ Robert Draper, Has the 'Libertarian Moment' Finally Arrived?, New York Times Magazine (August 7, 2016).

- ^ "Chris Sununu on the Issues". www.ontheissues.org. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ Voght, Kara (October 1, 2022). "The Republican Who's Thriving Despite Calling Trump 'F–king Crazy'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Josh Goodman, South Carolina's "Libertarian" Governor Archived 2016-09-16 at the Wayback Machine, Governing (August 4, 2008).

- ^ "Libertarians go local". Washington Examiner. August 12, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Ekins, Emily (September 26, 2011). "Is Half the Tea Party Libertarian?". Reason. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Kirby, David; Ekins, Emily McClintock (August 6, 2012). "Libertarian Roots of the Tea Party". Cato. Archived from the original on December 4, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Republicans are embracing crypto". Marketplace. July 17, 2024.

- ^ "Trump's techno-libertarian dream team goes to Washington". Vox. November 11, 2024.

- ^ "Elon Musk's Twist On Tech Libertarianism Is Blowing Up On Twitter". Politico. November 23, 2024.

- ^ "'Techno libertarians': Why Elon Musk is supporting Donald Trump in the US election". Euronews. October 30, 2024.

- ^ "Vivek Ramaswamy Debuts 'National Libertarianism' at NatCon 4". Reason. July 12, 2024.

- ^ "The Rise of the New Right at the Republican National Convention". New Yorker. July 18, 2024.

- ^ "Musk and Ramaswamy defend foreign worker visas, sparking MAGA backlash". CNN. December 27, 2024.

- ^ "Musk and Ramaswamy spar with Trump supporters over support for H-1B work visas". ABC News. December 28, 2024.

- ^ Silver, Nate (November 22, 2016). "Education, Not Income, Predicted Who Would Vote For Trump". FiveThirtyEight.

- ^ Cohn, Nate (August 17, 2023). "The 6 Kinds of Republican Voters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 12, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ Slomp, Hans (2011). Europe: A Political Profile. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-313-39182-8.

Most European liberals are Conservative Liberals, located at the right end of the left-right line, exactly opposite the American liberals' position. If transplanted to the United States, they would occupy the Left wing and the center of the Republican Party. Only the less numerous social liberals resemble American liberals.

- ^ "Losing Its Preference: Affirmative Action Fades as Issue". The Washington Post. 1996. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017.

- ^ Silverleib, Alan. "Analysis: An autopsy of liberal Republicans". cnn.com. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Pear, Robert (June 19, 2001). "Several G.O.P. Senators Back Money for Stem Cell Research". The New York Times. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Tatum, Sophie (December 20, 2018). "3 Kansas legislators switch from Republican to Democrat". CNN. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Weiner, Rachel. "Charlie Crist defends party switch". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Hornick, Ed; Walsh, Deidre. "Longtime GOP Sen. Arlen Specter becomes Democrat". CNN. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Plott, Elaina (October 6, 2018). "Two Moderate Senators, Two Very Different Paths". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Faludi, Susan (July 5, 2018). "Opinion - Senators Collins and Murkowski, It's Time to Leave the G.O.P." The New York Times. Retrieved February 23, 2019 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Petre, Linda (September 25, 2018). "Kavanaugh's fate rests with Sen. Collins". TheHill. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Connolly, Griffin (October 9, 2018). "Sen. Lisa Murkowski Could Face Reprisal from Alaska GOP". rollcall.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Bacon, Perry (March 30, 2018). "How A Massachusetts Republican Became One Of America's Most Popular Politicians". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ "If moderate Republicans don't want to go to Washington, how will things ever change?". BostonGlobe.com. November 18, 2021.

- ^ "Nevada governor signs new abortion protections into law". NBC News. March 31, 2023.

- ^ Gibson, Brittany (August 11, 2023). "Pennsylvania GOP Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick attracts an anti-abortion challenger". POLITICO. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ "Republican Mike Lawler retains pivotal suburban NYC House seat". POLITICO. November 6, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ "Republican David Valadao, Democrat George Whitesides win US House races in California". AP News. November 13, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ Pitofsky, Marina (January 10, 2021). "Colin Powell: 'I can no longer call myself a fellow Republican'". The Hill. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ "Panel Study of the MAGA Movement". University of Washington. January 6, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

- ^ Gabbatt, Adam; Smith, David (August 19, 2023). "'America First 2.0': Vivek Ramaswamy pitches to be Republicans' next Trump". the Guardian. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

- ^ Ball, Molly (January 23, 2024). "The GOP Wants Pure, Uncut Trumpism". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Arhin, Kofi; Stockemer, Daniel; Normandin, Marie-Soleil (May 29, 2023). "THE REPUBLICAN TRUMP VOTER: A Populist Radical Right Voter Like Any Other?". World Affairs. 186 (3). doi:10.1177/0043820023117681 (inactive July 12, 2025). ISSN 1940-1582.

In this article, we first illustrate that the Republican Party, or at least the dominant wing, which supports or tolerates Donald Trump and his Make America Great Again (MAGA) agenda have become a proto-typical populist radical right-wing party (PRRP).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Aratani, Lauren (February 26, 2021). "Republicans unveil two minimum wage bills in response to Democrats' push". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

In keeping with the party's deep division between its dominant Trumpist faction and its more traditionalist party elites, the twin responses seem aimed at appealing on one hand to its corporate-friendly allies and on the other hand to its populist rightwing base. Both have an anti-immigrant element.

- ^ Campani, Giovanna; Fabelo Concepción, Sunamis; Rodriguez Soler, Angel; Sánchez Savín, Claudia (December 2022). "The Rise of Donald Trump Right-Wing Populism in the United States: Middle American Radicalism and Anti-Immigration Discourse". Societies. 12 (6): 154. doi:10.3390/soc12060154. ISSN 2075-4698.

- ^ Norris, Pippa (November 2020). "Measuring populism worldwide". Party Politics. 26 (6): 697–717. doi:10.1177/1354068820927686. ISSN 1354-0688. S2CID 216298689.

- ^ Cassidy, John (February 29, 2016). "Donald Trump is Transforming the G.O.P. Into a Populist, Nativist Party". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ ""National conservatives" are forging a global front against liberalism". The Economist. London. February 15, 2024. Archived from the original on February 20, 2024.

- ^ Zhou, Shaoqing (December 8, 2022). "The origins, characteristics and trends of neo-nationalism in the 21st century". International Journal of Anthropology and Ethnology. 6 (1) 18. doi:10.1186/s41257-022-00079-4. PMC 9735003. PMID 36532330.

On a practical level, the United Kingdom's withdrawal from the European Union and Trump's election as the United States president are regarded as typical events of neo-nationalism.

- ^ Katzenstein, Peter J. (March 20, 2019). "Trumpism is US". WZB | Berlin Social Science Center. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ DiSalvo, Daniel (Fall 2022). "Party Factions and American Politics". National Affairs. Archived from the original on March 23, 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ^ Lowndes, Joseph (2019). "Populism and race in the United States from George Wallace to Donald Trump". In de la Torre, Carlos (ed.). Routledge Handbook of Global Populism. London & New York: Routledge. "Trumpism" section, pp. 197–200. ISBN 978-1315226446.

Trump unabashedly employed the language of white supremacy and misogyny, rage and even violence at Trump rallies was like nothing seen in decades.

- ^ Bennhold, Katrin (September 7, 2020). "Trump Emerges as Inspiration for Germany's Far Right". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Gardner, J.A.; Charles, G.U. (2023). Election Law in the American Political System. Aspen Casebook Series. Aspen Publishing. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-5438-2683-8. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Kleinfeld, Rachel (September 15, 2022). "Five Strategies to Support U.S. Democracy". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on September 15, 2022.

- ^ Falk, Thomas O (November 8, 2023). "Why are US Republicans pushing for aid to Israel but not Ukraine?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Riccardi, Nicholas (February 19, 2024). "Stalled US aid for Ukraine underscores GOP's shift away from confronting Russia". Associated Press. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Lillis, Mike (February 28, 2024). "GOP strained by Trump-influenced shift from Reagan on Russia". The Hill. Archived from the original on February 28, 2024. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

Experts say a variety of factors have led to the GOP's more lenient approach to Moscow, some of which preceded Trump's arrival on the political scene ... Trump's popularity has only encouraged other Republicans to adopt a soft-gloves approach to Russia.

- ^ Ball, Molly (February 23, 2024). "How Trump Turned Conservatives Against Helping Ukraine". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Jonathan, Chait (February 23, 2024). "Russian Dolls Trump has finally remade Republicans into Putin's playthings". Intelligencer. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

But during his time in office and after, Trump managed to create, from the grassroots up, a Republican constituency for Russia-friendly policy ... Conservatives vying to be the Trumpiest of them all have realized that supporting Russia translates in the Republican mind as a proxy for supporting Trump. Hence the politicians most willing to defend his offenses against democratic norms — Marjorie Taylor Greene, Jim Jordan, Tommy Tuberville, Mike Lee, J. D. Vance — hold the most anti-Ukraine or pro-Russia views. Conversely, the least-Trumpy Republicans, such as Mitch McConnell and Mitt Romney, have the most hawkish views on Russia. The rapid growth of Trump's once-unique pro-Russia stance is a gravitational function of his personality cult.

- ^ Lange, Jason (January 17, 2024). "Trump's rise sparks isolationist worries abroad, but voters unfazed". Reuters. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ^ Swan, Jonathan; Savage, Charlie; Haberman, Maggie (December 9, 2023). "Fears of a NATO Withdrawal Rise as Trump Seeks a Return to Power". New York Times. Retrieved December 10, 2023.

- ^ Baker, Peter (February 11, 2024). "Favoring Foes Over Friends, Trump Threatens to Upend International Order". The New York Times. ISSN 1553-8095. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ Cohn, Nate (August 17, 2023). "The 6 Kinds of Republican Voters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 12, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ Collinson, Stephen (October 4, 2023). "McCarthy became the latest victim of Trump's extreme GOP revolution". CNN. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Rocha, Alander (September 7, 2023). "Mike Rogers says of 'far-right wing' of GOP: 'You can't get rid of them'". AL. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Macpherson, James (July 24, 2021). "Far right tugs at North Dakota Republican Party". AP News. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "Fringe activists threaten Georgia GOP's political future". The Times Herald. May 15, 2023. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Baker, Paula; Critchlow, Donald T. (2020). The Oxford Handbook of American Political History. Oxford University Press. p. 387. ISBN 978-0190628697. Archived from the original on December 15, 2023. Retrieved April 23, 2021 – via Google Books.

Contemporary debate is fueled on one side by immigration restrictionists, led by President Donald Trump and other elected republicans, whose rhetorical and policy assaults on undocumented Latin American immigrants, Muslim refugees, and family-based immigration energized their conservative base.

- ^ Jones, Kent (2021). "Populism, Trade, and Trump's Path to Victory". Populism and Trade: The Challenge to the Global Trading System. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190086350.

- ^ Smith, Jordan Michael; Logis, Rich; Logis, Rich; Shephard, Alex; Shephard, Alex; Kipnis, Laura; Kipnis, Laura; Haas, Lidija; Haas, Lidija (October 17, 2022). "The Neocons Are Losing. Why Aren't We Happy?". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Archived from the original on May 5, 2023. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ Arias-Maldonado, Manuel (January 2020). "Sustainability in the Anthropocene: Between Extinction and Populism". Sustainability. 12 (6): 2538. Bibcode:2020Sust...12.2538A. doi:10.3390/su12062538. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ Spiegeleire, Stephan De; Skinner, Clarissa; Sweijs, Tim (2017). The Rise of Populist Sovereignism: What It Is, Where It Comes From, and What It Means for International Security and Defense. The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. ISBN 978-94-92102-59-1.

- ^ Isaac, Jeffrey (November 2017). "Making America Great Again?". Perspectives on Politics. 15 (3). Cambridge University Press: 625–631. doi:10.1017/S1537592717000871.

- ^ Blum, Rachel M. & Cowburn, Mike (2024). "How Local Factions Pressure Parties: Activist Groups and Primary Contests in the Tea Party Era". British Journal of Political Science. 54 (1). Cambridge University Press: 88–109. doi:10.1017/S0007123423000224. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson, Lauren R.; McCray, Deon; Ragusa, Jordan M. (January 11, 2018). "#NeverTrump: Why Republican members of Congress refused to support their party's nominee in the 2016 presidential election". Research & Politics. 5 (1). doi:10.1177/2053168017749383.

- ^ Swartz, David L. (May 27, 2022). "Trump divide among American conservative professors". Theory & Society. 52 (5): 739–769. doi:10.1007/s11186-023-09517-4. ISSN 1573-7853. PMC 10224651. PMID 37362148.

- ^ Will, George (June 22, 2018). "Opinion | Vote against the GOP this November". Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ McLaughlin, Dan (June 25, 2018). "Don't Throw the Republicans Out: A Response to George Will". National Review. Archived from the original on June 25, 2018. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Feaver, Peter (November 5, 2020). "What Trump's Near-Victory Means for Republican Foreign Policy". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ Elbeshbishi, Susan Page and Sarah. "Exclusive: Defeated and impeached, Trump still commands the loyalty of the GOP's voters". USA TODAY.

- ^ Stening, Tanner (May 26, 2022). "Do political endorsements still matter?". News @ Northeastern. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Homans, Charles (March 17, 2022). "Where Does American Democracy Go From Here?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 17, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Azari, Julia (March 15, 2022). "How Republicans Are Thinking About Trumpism Without Trump". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Helderman, Rosalind S.; Abutaleb, Yasmeen (November 2, 2022). "Biden warns GOP could set nation on 'path to chaos' as democratic system faces strain". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 3, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Arhin, Kofi; Stockemer, Daniel; Normandin, Marie-Soleil (May 29, 2023). "The Republican Trump Voter". World Affairs. 186 (3): 572–602. doi:10.1177/00438200231176818.

- ^ Lauter, David (February 14, 2021). "Loyalty to Trump remains the fault line for Republicans". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Dumcius, Gintautas. "Sen. John McCain backs up Mitt Romney, says Donald Trump's comments 'uninformed and indeed dangerous'", The Republican (March 3, 2016). Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ "Republicans oust Rep. Liz Cheney from leadership over her opposition to Trump and GOP election lies". Business Insider. May 12, 2021.

- ^ Enten, Harry (August 24, 2022). "Analysis: Cheney's loss may be the second worst for a House incumbent in 60 years". CNN. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ "Kinzinger gets pro-Trump primary challenger". The Hill. February 25, 2021.

- ^ "Trump endorses Murkowski primary opponent Kelly Tshibaka". Fox News. June 18, 2021.

- ^ "Jason Chaffetz says he's open to challenging Mitt Romney in Utah Senate primary". Washington Examiner. February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Dear Republican Trump haters – What did you get for your trade?". Washington Times. August 16, 2021.

- ^ Riley Roche, Lisa (May 16, 2024). "Sen. Mitt Romney says his views are tiny 'chicken wing' of GOP". Deseret News. p. 1. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Martin, Jonathan (September 17, 2021). "Ohio House Republican, Calling Trump 'a Cancer,' Bows Out of 2022". The New York Times.

- ^ Colvin, Jill; Ramer, Holly (June 6, 2023). "Christie goes after Trump in presidential campaign launch, calling him a 'self-serving mirror hog'". ABC News.

- ^ Miller, Andrew (March 8, 2024). "Indiana GOP Sen. Todd Young renews his pledge not to support Trump in 2024". Fox News. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Williams, Paige (October 5, 2020). "Inside the Lincoln Project's War Against Trump". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Lerer, Lisa (July 26, 2023). "Republican Attack Ads in Iowa Show Conservative Voters Who Turned on Trump". The New York Times. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "Republican group airs anti-Trump advert on Fox News". The Independent. May 12, 2020. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "Centrist lawmakers band together to demand House reforms for the next speaker". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^ "Three Minor Parties Merge Ahead of April Elections". The Hill. November 7, 2007.

Rep. Mike Castle (R-Del.), a longtime member and former co-chairman of the Tuesday Group, said lawmakers launched the PAC to help vulnerable centrists as well as liberal-leaning Republicans running for open congressional seats.

- ^ Kapur, Sahil (July 18, 2023). "Centrist Republicans warn far-right tactics could backfire in funding fight". NBC News. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Pengelly, Martin; Greve, Joan E. (October 4, 2023). "Republicans Jim Jordan and Steve Scalise launch House speakership bids". The Guardian.

- ^ "The House Freedom Caucus' newest problem: It's shrinking". MSNBC.com. March 21, 2024. Retrieved February 11, 2025.

- ^ Stanage, Niall (January 8, 2023). "The Memo: Republicans stumble out of the starting blocks". The Hill. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved February 11, 2025.

- ^ Stening, Tanner (June 5, 2023). "Is the US now a four-party system? Progressives split Democrats, and far-right divides Republicans". Northeastern Global News. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ Clarke, Andrew J. (July 2020). "Party Sub-Brands and American Party Factions". American Journal of Political Science. 64 (3): 9. doi:10.1111/ajps.12504.

- ^ Lizza, Ryan (December 7, 2015). "A House divided". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

Meadows is one of the more active members of the House Freedom Caucus, an invitation-only group of about forty right-wing conservatives that formed at the beginning of this year.

- ^ Wong, Scott; Allen, Jonathan (April 28, 2022). "Trump expected to stump for Illinois congresswoman in primary fight against fellow lawmaker". NBC News. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

Rep. Mary Miller, a member of the far-right Freedom Caucus, said Trump has vowed to campaign for her ahead of her primary against GOP Rep. Rodney Davis.

- ^ Blanco, Adrian; Sotomayor, Marianna; Dormido, Hannah (April 17, 2023). "Meet 'the five families' that wield power in McCarthy's House majority". Washington Post. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ "Black and Tan Republicans" in Andrew Cunningham McLaughlin and Albert Bushnell Hart, eds. Cyclopedia of American Government (1914) . p. 133. online

- ^ Heersink, Boris; Jenkins, Jeffery A. (April 2020). "Whiteness and the Emergence of the Republican Party in the Early Twentieth-Century South". Studies in American Political Development. 34 (1): 71–90. doi:10.1017/S0898588X19000208. ISSN 0898-588X. S2CID 213551748.

- ^ "Stalwart". Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ a b Peskin, Allan (1984–1985). "Who Were the Stalwarts? Who Were Their Rivals? Republican Factions in the Gilded Age". Political Science Quarterly. 99 (4): 703–716. doi:10.2307/2150708. JSTOR 2150708.

- ^ a b "Radical Republican". Archived from the original on November 6, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ Milkis, Sidney (October 4, 2016). "Theodore Roosevelt: Domestic Affairs". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Arnold, Peri E. (October 4, 2016). "William Taft: Domestic Affairs". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Wolfensberger, Don (December 12, 2018). "Opening day of new Congress: Not always total joy". The Hill. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Michael Wolraich. Unreasonable Men: Theodore Roosevelt and the Republican Rebels Who Created Progressive Politics (2014).

- ^ a b Reinhard, David W. (1983). The Republican Right since 1945. The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-0-8131-5449-7.

- ^ Reinhard, David W. (1983). The Republican Right since 1945. The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 15–20. ISBN 978-0-8131-5449-7.

- ^ Reinhard, David W. (1983). The Republican Right since 1945. The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-0-8131-5449-7.

- ^ Towler, Christopher (December 6, 2018). "The John Birch Society is still influencing American politics, 60 years after its founding". The Conversation. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ Dallek, Matthew (2023). Birchers: How the John Birch Society Radicalized the American Right. Basic Books.

- ^ "Debunking a Longstanding Myth About William F. Buckley". POLITICO. March 31, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ "Analysis: An autopsy of liberal Republicans - CNN.com". cnn.com. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Blue wave that swamped New England endangers Yankee Republicans". The CT Mirror. November 16, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Will Pennsylvania Loss Revive Rockefeller Republicans?". Christian Science Monitor. November 8, 1991. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ Lind, Michael. Up From Conservatism. p. 263.

- ^ "How Watergate Helped Republicans—And Gave Us Trump". Politico. May 22, 2017.

- ^ Adrian Wooldridge and John Micklethwait. The Right Nation: Conservative Power in America (2004).

- ^ Connolly, Katie (September 16, 2010). "What exactly is the Tea Party?". bbc.com. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Brown, Heath (February 24, 2017). "Do anti-Trump protests really compare to 2009 Tea Party?". TheHill. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Gallup: Tea Party's top concerns are debt, size of government The Hill, July 5, 2010

- ^ Somashekhar, Sandhya (September 12, 2010). Tea Party DC March: "Tea party activists march on Capitol Hill". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Good, Chris (October 6, 2010). "On Social Issues, Tea Partiers Are Not Libertarians". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- ^ Jonsson, Patrik (November 15, 2010). "Tea party groups push GOP to quit culture wars, focus on deficit". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- ^ Roy, Avik. April 7, 2012. The Tea Party's Plan for Replacing Obamacare. Forbes. Retrieved: March 6, 2015.

- ^ Somin, Ilya, The Tea Party Movement and Popular Constitutionalism (May 26, 2011). Northwestern University Law Review Colloquy, Vol. 105, p. 300, 2011 (Colloquy on the Constitutional Politics of the Tea Party Movement), George Mason Law & Economics Research Paper No. 11-22, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1853645

- ^ a b Mead, Walter Russell (March–April 2011). "The Tea Party and American Foreign Policy: What Populism Means for Globalism". Foreign Affairs. pp. 28–44.

- ^ "Boston Tea Party Is Protest Template". UPI. April 20, 2008.

- ^ Jossey, Paul H. (August 14, 2016). "How We Killed the Tea Party". POLITICO Magazine. Archived from the original on August 14, 2016.

- ^ "Allen West joins congressional Tea Party Caucus". Sun Sentinel. February 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Lieb, David (August 6, 2012). "Tea party focused on coming GOP Senate primaries". The Tribune-Democrat. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ "Exclusive Tim Scott Interview: No Racism in Tea Party". Blogs.cbn.com. September 21, 2010.

- ^ a b Rudin, Ken (July 30, 2012). "Latest Tea Party Vs. GOP Establishment Battle Comes Tuesday In Texas". NPR.org. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ "Ted Cruz: His tea party background, positions on health care and taxes". mercurynews.com. Associated Press. February 3, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Herb, Jeremy (January 23, 2017). "Trump's tea party budget chief on collision course with GOP hawks". Politico.

- ^ Tea Party canvass results, Category: "What They Believe" A Party Face Washington Post October 24, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ Green, Joshua (August 5, 2011). "The Tea Party's Brain". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ Williams, Juan (May 10, 2011). "The Surprising Rise of Rep. Ron Paul". Fox News. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Barone, Michael and Richard E. Cohen. The Almanac of American Politics, 2010 (2009). 1,900 pages of minute, nonpartisan detail on every state and district and member of Congress.

- Baker, Peter, and Susan Glasser. The Divider: Trump in the White House, 2017-2021 (2022) excerpt

- Dyche, John David. Republican Leader: A Political Biography of Senator Mitch McConnell (2009).

- Edsall, Thomas Byrne. Building Red America: The New Conservative Coalition and the Drive For Permanent Power (2006). Sophisticated analysis by liberal.

- Crane, Michael. The Political Junkie Handbook: The Definitive Reference Book on Politics (2004). Nonpartisan.

- Frank, Thomas. What's the Matter with Kansas (2005). Attack by a liberal.

- Frohnen, Bruce, Beer, Jeremy and Nelson, Jeffery O., eds. American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia (2006). 980 pages of articles by 200 conservative scholars.

- Hamburger, Tom and Peter Wallsten. One Party Country: The Republican Plan for Dominance in the 21st Century (2006). Hostile.

- Hemmer, Nicole. Partisans: The Conservative Revolutionaries Who Remade American Politics in the 1990s (2022)

- Hewitt, Hugh. GOP 5.0: Republican Renewal Under President Obama (2009).

- Ross, Brian. "The Republican Un-Civil War – The Neocons and the Tea Party Fight for Control of the GOP" (August 9, 2012). Truth-2-Power.

- Wooldridge, Adrian and John Micklethwait. The Right Nation: Conservative Power in America (2004). Sophisticated nonpartisan analysis.

- "A Guide to the Republican Herd" (October 5, 2006). The New York Times.

- "Belief Spectrum Brings Party Splits" (October 4, 1998). The Washington Post.

KSF

KSF