Fernando Pessoa

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 46 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 46 min

Fernando Pessoa | |

|---|---|

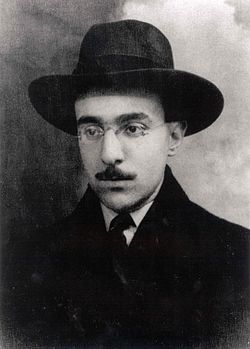

Portrait of Pessoa 1914 | |

| Born | Fernando António Nogueira de Seabra Pessoa 13 June 1888 Lisbon, Portugal |

| Died | 30 November 1935 (aged 47) Lisbon, Portugal |

| Pen name | Alberto Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos, Ricardo Reis, Bernardo Soares, etc. |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | Portuguese, English, French |

| Alma mater | University of Lisbon |

| Period | 1912–1935 |

| Genre | Poetry, essay, fiction |

| Literary movement | Modernism |

| Notable works | Mensagem (1934) The Book of Disquiet (1982) |

| Notable awards |

|

| Partner | Ophelia Queiroz (girlfriend) |

| Signature | |

Fernando António Nogueira de Seabra Pessoa (/pɛˈsoʊə/;[1] Portuguese: [fɨɾˈnɐ̃du pɨˈsoɐ]; 13 June 1888 – 30 November 1935) was a Portuguese poet, writer, literary critic, translator, and publisher. He has been described as one of the most significant literary figures of the 20th century and one of the greatest poets in the Portuguese language. He also wrote in and translated from English and French.

Pessoa was a prolific writer both in his own name and approximately seventy-five other names, of which three stand out: Alberto Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos, and Ricardo Reis. He did not define these as pseudonyms because he felt that this did not capture their true independent intellectual life and instead called them heteronyms, a term he invented.[2] These imaginary figures sometimes held unpopular or extreme views.

Early life

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

Pessoa was born in Lisbon on 13 June 1888. When Pessoa was five, his father, Joaquim de Seabra Pessôa, died of tuberculosis, and less than seven months later his younger brother Jorge, aged one, also died (2 January 1889).[3] After the second marriage of his mother, Maria Magdalena Pinheiro Nogueira, by a proxy wedding to João Miguel dos Santos Rosa, Fernando sailed with his mother for South Africa in early 1896 to join his stepfather, a military officer appointed Portuguese consul in Durban, capital of the former British Colony of Natal.[4]

In a letter dated 8 February 1918, Pessoa wrote:

There is only one event in the past which has both the definiteness and the importance required for rectification by direction; this is my father's death, which took place on 13 July 1893. My mother's second marriage (which took place on 30 December 1895) is another date which I can give with preciseness and it is important for me, not in itself, but in one of its results – the circumstance that, my stepfather becoming Portuguese Consul in Durban (Natal), I was educated there, this English education being a factor of supreme importance in my life, and, whatever my fate be, indubitably shaping it.

The dates of the voyages related to the above event are (as nearly as possible):

1st. voyage to Africa – left Lisbon beginning January 1896.

Return – left Durban in the afternoon of 1st. August 1901.

2nd. voyage to Africa – left Lisbon about 20th. September 1902.

Return – left Durban about 20th. August 1905.[5]

The young Pessoa received his early education at St. Joseph Convent School, a Roman Catholic grammar school run by Irish and French nuns. He moved to the Durban High School in April 1899, becoming fluent in English and developing an appreciation for English literature. During the Matriculation Examination, held at the time by the University of the Cape of Good Hope (forerunner of the University of Cape Town), in November 1903, he was awarded the recently created Queen Victoria Memorial Prize for best paper in English. While preparing to enter university, he also attended the Durban Commercial High School during one year, taking night classes.[6]

Meanwhile, Pessoa started writing short stories in English, some under the name of David Merrick, many of which he left unfinished.[3] At the age of sixteen, The Natal Mercury (edition of 6 July 1904) published his satirical poem "Hillier did first usurp the realms of rhyme ...", under the name of C. R. Anon (anonymous), along with a brief introductory text: "I read with great amusement...".[7][8] In December, The Durban High School Magazine published his essay "Macaulay".[9] From February to June 1905, in the section "The Man in the Moon", The Natal Mercury also published at least four sonnets by Fernando Pessoa: "Joseph Chamberlain", "To England I", "To England II" and "Liberty".[10] His poems often carried humorous versions of Anon as the author's name. Pessoa started using pen names quite young. The first one, still in his childhood, was Chevalier de Pas, supposedly a French noble. In addition to Charles Robert Anon and David Merrick, the young writer also signed up, among other pen names, as Horace James Faber, Alexander Search, and other meaningful names.[6]

In the preface to The Book of Disquiet, Pessoa wrote about himself:

Nothing had ever obliged him to do anything. He had spent his childhood alone. He never joined any group. He never pursued a course of study. He never belonged to a crowd. The circumstances of his life were marked by that strange but rather common phenomenon – perhaps, in fact, it's true for all lives – of being tailored to the image and likeness of his instincts, which tended towards inertia and withdrawal.

The young Pessoa was described by a schoolfellow as follows:

I cannot tell you exactly how long I knew him, but the period during which I received most of my impressions of him was the whole of the year 1904 when we were at school together. How old he was at this time I don't know, but judge him to have 15 or 16. [...]

He was pale and thin and appeared physically to be very imperfectly developed. He had a narrow and contracted chest and was inclined to stoop. He had a peculiar walk and some defect in his eyesight gave to his eyes also a peculiar appearance, the lids seemed to drop over the eyes. [...]

He was regarded as a brilliant clever boy as, in spite of the fact that he had not spoken English in his early years, he had learned it so rapidly and so well that he had a splendid style in that language. Although younger than his schoolfellows of the same class he appeared to have no difficulty in keeping up with and surpassing them in work. For one of his age, he thought much and deeply and in a letter to me once complained of "spiritual and material encumbrances of most especial adverseness". [...]

He took no part in athletic sports of any kind and I think his spare time was spent on reading. We generally considered that he worked far too much and that he would ruin his health by so doing.[11]

Ten years after his arrival, he sailed for Lisbon by East through the Suez Canal on board the "Herzog", leaving Durban for good at the age of seventeen. This journey inspired the poems "Opiário" (dedicated to his friend, the poet and writer Mário de Sá-Carneiro) published in March 1915, in the literary journal Orpheu nr.1[12] and "Ode Marítima" (dedicated to the futurist painter Santa-Rita) published in June 1915, in Orpheu nr.2[13] by his heteronym Álvaro de Campos.

Lisbon revisited

[edit]

While his family remained in South Africa, Pessoa returned to Lisbon in 1905 to study diplomacy. After a period of illness, and two years of poor results, a student strike against the dictatorship of Prime Minister João Franco put an end to his formal studies. Pessoa became an autodidact and a devoted reader who spent much of his time in libraries.[14] In August 1907, he started working as a practitioner at R.G. Dun & Company, an American mercantile information agency (currently D&B, Dun & Bradstreet). His grandmother died in September and left him a small inheritance, which he spent on setting up his own publishing house, the "Empreza Ibis". The venture was not successful and closed down in 1910, but the name ibis,[15] the sacred bird of Ancient Egypt and inventor of the alphabet in Greek mythology, would remain an important symbolic reference for him.[citation needed]

Pessoa returned to his uncompleted formal studies, complementing his British education with self-directed study of Portuguese culture. The pre-revolutionary atmosphere surrounding the assassination of King Charles I and Crown Prince Luís Filipe in 1908, and the patriotic outburst resulting from the successful republican revolution in 1910, influenced the development of the budding writer; as did his step-uncle, Henrique dos Santos Rosa, a poet and retired soldier, who introduced the young Pessoa to Portuguese poetry, notably the romantics and symbolists of the 19th century.[16]

In 1912, Fernando Pessoa entered the literary world with a critical essay, published in the cultural journal A Águia, which triggered one of the most important literary debates in the Portuguese intellectual world of the 20th century: the polemic regarding a super-Camões. In 1915 a group of artists and poets, including Fernando Pessoa, Mário de Sá-Carneiro and Almada Negreiros, created the literary magazine Orpheu,[17] which introduced modernist literature to Portugal. Only two issues were published (Jan–Feb–Mar and Apr–May–Jun 1915), the third failed to appear due to funding difficulties. Lost for many years, this issue was finally recovered and published in 1984.[18] Among other writers and poets, Orpheu published Pessoa, orthonym, and the modernist heteronym, Álvaro de Campos.[citation needed]

Along with the artist Ruy Vaz, Pessoa also founded the art journal Athena (1924–25),[19] in which he published verses under the heteronyms Alberto Caeiro and Ricardo Reis. In addition to his profession as free-lance commercial translator, Fernando Pessoa undertook intense activity as a writer, literary critic and political analyst, contributing to the journals and newspapers A Águia (1912–13), A República (1913), Theatro (1913), A Renascença (1914), O Raio (1914), A Galera (1915), Orpheu (1915), O Jornal (1915), Eh Real! (1915), Exílio (1916), Centauro (1916), A Ideia Nacional (1916), Terra Nossa (1916), O Heraldo (1917), Portugal Futurista (1917), Acção (1919–20), Ressurreição (1920), Contemporânea (1922–26), Athena (1924–25), Diário de Lisboa (1924–35), Revista de Comércio e Contabilidade (1926), Sol (1926), O Imparcial (1927), Presença (1927–34), Revista Solução Editora (1929–1931), Notícias Ilustrado (1928–30), Girassol (1930), Revolução (1932), Descobrimento (1932), Fama (1932–33), Fradique (1934) and Sudoeste (1935).[citation needed]

Pessoa the flâneur

[edit]After his return to Portugal, when he was seventeen, Pessoa barely left his beloved city of Lisbon, which inspired the poems "Lisbon Revisited" (1923 and 1926), written under the heteronym Álvaro de Campos. From 1905 to 1920, when his family returned from Pretoria after the death of his stepfather, he lived in fifteen different locations in the city,[20] moving from one rented room to another depending on his fluctuating finances and personal troubles.

Pessoa adopted the detached perspective of the flâneur Bernardo Soares, one of his heteronyms.[21] This character was supposedly an accountant, working for Vasques, the boss of an office located in Douradores Street. Soares also supposedly lived in the same downtown street, a world that Pessoa knew quite well due to his long career as freelance correspondence translator. Indeed, from 1907 until his death in 1935, Pessoa worked in twenty-one firms located in Lisbon's downtown, sometimes in two or three of them simultaneously.[22] In The Book of Disquiet, Bernardo Soares describes some of these typical places and describes one's "atmosphere". In his daydream soliloquy he also wrote about Lisbon in the first half of the 20th century. Soares describes crowds in the streets, buildings, shops, traffic, the river Tagus, the weather, and even its author, Fernando Pessoa:

Fairly tall and thin, he must have been about thirty years old. He hunched over terribly when sitting down but less so standing up, and he dressed with a carelessness that wasn't entirely careless. In his pale, uninteresting face there was a look of suffering that didn't add any interest, and it was difficult to say just what kind of suffering this look suggested. It seemed to suggest various kinds: hardships, anxieties, and the suffering born of the indifference that comes from having already suffered a lot.[23]

A statue of Pessoa sitting at a table (below) can be seen outside A Brasileira, one of the preferred places of young writers and artists of Orpheu's group during the 1910s. This coffeehouse, in the aristocratic district of Chiado, is quite close to Pessoa's birthplace: 4, São Carlos Square (just in front of Lisbon's Opera House, where stands another statue of the writer), one of the most elegant neighborhoods of Lisbon.[24] Later on, Pessoa was a frequent customer at Martinho da Arcada, a centennial coffeehouse in Comercio Square, surrounded by ministries, almost an "office" for his private business and literary concerns, where he used to meet friends in the 1920s and 1930s.[citation needed]

In 1925, Pessoa wrote in English a guidebook to Lisbon but it remained unpublished until 1992.[25][26]

Literature and mysticism

[edit]Pessoa translated a number of Portuguese books into English such as The Songs of Antonio Botto.[27] He also translated various works into Portuguese such as The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne,[28] and the short stories "The Theory and the Hound", "The Roads We Take" and "Georgia's Ruling" by O. Henry.[29] He has also translated into Portuguese the poems "Godiva" by Alfred Tennyson, "Lucy" by William Wordsworth, "Catarina to Camoens" by Elizabeth Barrett Browning,[30] "Barbara Frietchie" by John Greenleaf Whittier,[31] and "The Raven", "Annabel Lee" and "Ulalume" by Edgar Allan Poe[32] who, along with Walt Whitman, strongly influenced him.

As a translator, Pessoa had his own method:

Automatic writing sample.

A poem is an intellectualized impression, an idea made emotion, communicated by others by means of a rhythm. This rhythm is double in one, like the concave and convex aspects of the same arc: it is made up of a verbal or musical rhythm and of a visual or image rhythm which concurs inwardly with it. The translation of a poem should therefore conform absolutely (1) to the idea or emotion which constitutes the poem, (2) to the verbal rhythm in which that idea or emotion is expressed; it should conform relatively to the inner or visual rhythm, keeping to the images themselves when it can, but keeping always to the type of image. It was on this criterion that I based my translation into Portuguese of Poe's "Annabel Lee" and "Ulalume", which I translated, not because of their great intrinsic worth, but because they were a standing challenge to translators.[33]

In addition, Pessoa translated into Portuguese some books by the leading theosophists Helena Blavatsky, Charles Webster Leadbeater, Annie Besant, and Mabel Collins.[34]

In 1912–14, while living with his aunt "Anica" and cousins,[35] Pessoa took part in "semi-spiritualist sessions" that were carried out at home, but he was considered a "delaying element" by the other members of the sessions. Pessoa's interest in spiritualism was truly awakened in the second half of 1915, while translating theosophist books. This was further deepened in the end of March 1916, when he suddenly started having experiences where he believed he became a medium, having experimented with automatic writing.[36] On June 24, 1916, Pessoa wrote an impressive letter to his aunt and godmother,[37] then living in Switzerland with her daughter and son-in-law, in which he describes this "mystery case" that surprised him.[36]

Besides automatic writing, Pessoa stated also that he had "astral" or "etherial visions" and was able to see "magnetic auras" similar to radiographic images. He felt "more curiosity than fear", but was respectful towards this phenomenon and asked secrecy, because "there is no advantage, but many disadvantages" in speaking about this. Mediumship exerted a strong influence in Pessoa's writings, who felt "sometimes suddenly being owned by something else" or having a "very curious sensation" in the right arm, which was "lifted into the air" without his will. Looking in the mirror, Pessoa saw several times what appeared to be the heteronyms: his "face fading out" and being replaced by the one of "a bearded man", or in another instance, four men in total.[36]

Pessoa also developed a strong interest in astrology, becoming a competent astrologer. He elaborated hundreds of horoscopes, including well-known people such as William Shakespeare, Lord Byron, Oscar Wilde, Chopin, Robespierre, Napoleon I, Benito Mussolini, Wilhelm II, Leopold II of Belgium, Victor Emmanuel III, Alfonso XIII, or the Kings Sebastian and Charles of Portugal, and Salazar. In 1915, he created the heteronym Raphael Baldaya, an astrologer who planned to write "System of Astrology" and "Introduction to the Study of Occultism". Pessoa established the pricing of his astrological services from 500 to 5,000 réis and made horoscopes of relatives, friends, customers, also of himself and astonishingly of the heteronyms and journals as Orpheu.

The characters of the three main heteronyms were designed according to their horoscopes, with special reference to Mercury, the planet of literature. Each was also assigned to one of the four astral elements: air, fire, water and earth. For Pessoa, his heteronyms, taken together with his actual self, embodied the full principles of ancient knowledge. Astrology was part of his everyday life and he actively practiced it until his death.[38]

"I know not what tomorrow will bring".

He died the next day, 30 November 1935.

As a mysticist, Pessoa was an enthusiast of esotericism, occultism, hermetism, numerology and alchemy. Along with spiritualism and astrology, he also paid attention to gnosticism, neopaganism, theosophy, rosicrucianism and freemasonry, which strongly influenced his literary work. He has declared himself a Pagan, in the sense of an "intellectual mystic of the sad race of the Neoplatonists from Alexandria" and a believer in "the Gods, their agency and their real and materially superior existence".[39] His interest in occultism led Pessoa to correspond with Aleister Crowley and later helped him to elaborate a fake suicide, when Crowley visited Portugal in 1930.[40] Pessoa translated Crowley's poem "Hymn To Pan"[41] into Portuguese, and the catalogue of Pessoa's library shows that he possessed Crowley's books Magick in Theory and Practice and Confessions. Pessoa also wrote on Crowley's doctrine of Thelema in several fragments, including Moral.[42]

Pessoa declared about secret societies:

I am also very interested in knowing whether a second edition is shortly to be expected of Athur Edward Waite's The Secret Tradition in Freemasonery. I see that, in a note on page 14 of his Emblematic Freemasonery, published by you in 1925, he says, in respect of the earlier work: "A new and revised edition is in the forefront of my literary schemes." For all I know, you may already have issued such an edition; if so, I have missed the reference in The Times Literary Supplement. Since I am writing on these subjects, I should like to put a question which perhaps you can reply to; but please do not do so if the reply involves any inconvenience. I believe The Occult Review was, or is, issued by yourselves; I have not seen any number for a long time. My question is in what issue of that publication – it was certainly a long while ago – an article was printed relating to the Roman Catholic Church as a Secret Society, or, alternatively, to a Secret Society within the Roman Catholic Church.[43]

Literary critic Martin Lüdke described Pessoa's philosophy as a kind of pandeism, especially those writings under the heteronym Alberto Caeiro.[44]

Writing a lifetime

[edit]

In his early years, Pessoa was influenced by major English classic poets such as Shakespeare, Milton and Pope, and romantics like Shelley, Byron, Keats, Wordsworth, Coleridge and Tennyson.[45] After his return to Lisbon in 1905, Pessoa was influenced by French symbolists and decadents such as Charles Baudelaire, Maurice Rollinat, and Stéphane Mallarmé. He was also importantly influenced by Portuguese poets such as Antero de Quental, Gomes Leal, Cesário Verde, António Nobre, Camilo Pessanha and Teixeira de Pascoaes. Later on, he was also influenced by the modernists W. B. Yeats, James Joyce, Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, among many other writers.[3]

During World War I, Pessoa wrote to a number of British publishers, namely Constable & Co. Ltd. (currently Constable & Robinson), trying to arrange publication of his collection of English verse The Mad Fiddler (unpublished during his lifetime), but it was refused. However, in 1920, the prestigious literary journal Athenaeum included one of those poems.[46] Since the attempt at British publication failed, in 1918 Pessoa published in Lisbon two slim volumes of English verse: Antinous[47] and 35 Sonnets,[48] received by the British literary press without enthusiasm.[49] Along with some friends, he founded another publishing house, Olisipo, which published in 1921 a further two English poetry volumes: English Poems I–II and English Poems III by Fernando Pessoa. In his publishing house, Pessoa also issued some books by his friends: A Invenção do Dia Claro (The Invention of the Clear Day) by José de Almada Negreiros, Canções (Songs) by António Botto, and Sodoma Divinizada (Deified Sodom) by Raul Leal (Henoch). Olisipo closed down in 1923, following the scandal known as "Literatura de Sodoma" (Literature of Sodom), which Pessoa started with his paper "António Botto e o Ideal Estético em Portugal" (António Botto and the Aesthetic Ideal in Portugal), published in the journal Contemporanea.[50]

Politically, Pessoa described himself as "a British-style conservative, that is to say, liberal within conservatism and absolutely anti-reactionary," and adhered closely to the Spencerian individualism of his upbringing.[51] He described his brand of nationalism as "mystic, cosmopolitan, liberal, and anti-Catholic."[51] He was an outspoken elitist and aligned himself against communism, socialism, fascism and Catholicism.[52] He initially rallied to the First Portuguese Republic but the ensuing instability caused him to reluctantly support the military coups of 1917 and 1926 as a means of restoring order and preparing the transition to a new constitutional normality.[53][54] He wrote a pamphlet in 1928 supportive of the military dictatorship but after the establishment of the New State, in 1933, Pessoa became disenchanted with the regime and wrote critically of Salazar and fascism in general, maintaining a hostile stance towards its corporatist program, illiberalism, and censorship.[55] In the beginning of 1935, Pessoa was banned by the Salazar regime, after he wrote in defense of Freemasonry.[56][57] The regime also suppressed two articles Pessoa wrote in which he condemned Mussolini's invasion of Abyssinia and fascism as a threat to human liberty everywhere.[58]

On 29 November 1935, Pessoa was taken to the Hospital de São Luís, suffering from abdominal pain and a high fever; there he wrote, in English, his last words: "I know not what tomorrow will bring."[59] He died the next day, 30 November 1935, around 8 pm, aged 47. His cause of death is commonly given as cirrhosis of the liver, due to alcoholism,[60][59][61] though this is disputed: others attribute his death to pancreatitis (again from alcoholism),[62][63] or other ailments.[64]

In his lifetime, he published four books in English and one alone in Portuguese: Mensagem (Message). However, he left a lifetime of unpublished, unfinished or just sketchy work in a domed, wooden trunk (25,574[65] manuscript and typed pages which have been housed in the Portuguese National Library since 1988). The heavy burden of editing this huge work is still in progress. In 1985 (fifty years after his death), Pessoa's remains were moved to the Hieronymites Monastery, in Lisbon, where Vasco da Gama, Luís de Camões, and Alexandre Herculano are also buried.[66] Pessoa's portrait was on the 100-escudo banknote.

The triumphant day

[edit][…] on 8 March 1914 – I found myself standing before a tall chest of drawers, took up a piece of paper, began to write, remaining upright all the while since I always stand when I can. I wrote thirty some poems in a row, all in a kind of ecstasy, the nature of which I shall never fathom. It was the triumphant day of my life, and I shall never have another like it. I began with a title, The Keeper of Sheep. And what followed was the appearance of someone within me to whom I promptly assigned the name of Alberto Caeiro. Please excuse the absurdity of what I am about to say, but there had appeared within me, then and there, my own master. It was my immediate sensation. So much so that, with those thirty odd poems written, I immediately took up another sheet of paper and wrote as well, in a row, the six poems that make up "Oblique Rain" by Fernando Pessoa. Immediately and totally... It was the return from Fernando Pessoa/Alberto Caeiro to Fernando Pessoa alone. Or better still, it was Fernando Pessoa's reaction to his own inexistence as Alberto Caeiro.[67]

As the heteronym Coelho Pacheco, over a long period Pessoa's "triumphant day" was taken as real, however, it has been proved that this event was one more fiction created by Pessoa.[68]

Heteronyms

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

Pessoa's earliest heteronym, at the age of six, was Chevalier de Pas, a fictitious knight whom he wrote to himself as.[69] Other childhood heteronyms included the poet Dr. Pancrácio and short story writer David Merrick, followed by Charles Robert Anon, a young Englishman who became Pessoa's alter ego.[70][59] When Pessoa was a student at the University of Lisbon, Anon was replaced by Alexander Search. Search represented a transition heteronym that Pessoa used while searching to adapt to the Portuguese cultural reality. As a result, Pessoa would write many English poems, specifically sonnets, and short stories under the Search heteronym, including "A Very Original Dinner", which was posthumously published after its recovery and subsequent reproduction by Portuguese literary historian Maria Leonor Machado de Sousa.[71][72] After the 5 October 1910 revolution and its subsequently patriotic atmosphere, Pessoa created another alter ego, Álvaro de Campos, supposedly a Portuguese naval and mechanical engineer, who was born in Tavira, hometown of Pessoa's ancestors, and graduated in Glasgow.[69] Translator and literary critic Richard Zenith notes that Pessoa eventually established at least seventy-two heteronyms.[73] According to Pessoa himself, Zenith says, there were three main heteronyms of them all: Alberto Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos, and Ricardo Reis. Pessoa's heteronyms differ from pen names, as they possess distinct biographies, temperaments, philosophies, appearances, writing styles, and even signatures.[74] Thus, heteronyms often disagree on various topics as well as argue and discuss with each other about literature, aesthetics, philosophy, and so on.

Regarding the heteronyms, Pessoa wrote:

How do I write in the name of these three? Caeiro, through sheer and unexpected inspiration, without knowing or even suspecting that I'm going to write in his name. Ricardo Reis, after an abstract meditation, which suddenly takes concrete shape in an ode. Campos, when I feel a sudden impulse to write and don't know what. (My semi-heteronym Bernardo Soares, who in many ways resembles Álvaro de Campos, always appears when I'm sleepy or drowsy, so that my qualities of inhibition and rational thought are suspended; his prose is an endless reverie. He's a semi-heteronym because his personality, although not my own, doesn't differ from my own but is a mere mutilation of it. He's me without my rationalism and emotions. His prose is the same as mine, except for certain formal restraint that reason imposes on my own writing, and his Portuguese is exactly the same – whereas Caeiro writes bad Portuguese, Campos writes it reasonably well but with mistakes such as "me myself" instead of "I myself", etc.., and Reis writes better than I, but with a purism I find excessive...).[75]

Pessoa's heteronyms, pseudonyms, and characters

[edit]| No. | Name | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fernando Antonio Nogueira Pessoa | Himself | Commercial correspondent in Lisbon |

| 2 | Fernando Pessoa | Orthonym | Poet and prose writer |

| 3 | Fernando Pessoa | Autonym | Poet and prose writer |

| 4 | Fernando Pessoa | Heteronym | Poet; a pupil of Alberto Caeiro |

| 5 | Alberto Caeiro | Heteronym | Poet; author of O guardador de Rebanhos, O Pastor Amoroso and Poemas inconjuntos; master of heteronyms Fernando Pessoa, Álvaro de Campos, Ricardo Reis and António Mora |

| 6 | Ricardo Reis | Heteronym | Poet and prose writer, author of Odes and texts on the work of Alberto Caeiro |

| 7 | Federico Reis | Heteronym / Para-heteronym | Essayist; brother of Ricardo Reis, upon whom he writes |

| 8 | Álvaro de Campos | Heteronym | Poet and prose writer; a pupil of Alberto Caeiro |

| 9 | António Mora | Heteronym | Philosopher and sociologist; theorist of Neopaganism; a pupil of Alberto Caeiro |

| 10 | Claude Pasteur | Heteronym / Semi-heteronym | French translator of Cadernos de reconstrução pagã conducted by António Mora |

| 11 | Bernardo Soares | Heteronym / Semi-heteronym | Poet and prose writer; author of the second phase of The Book of Disquiet |

| 12 | Vicente Guedes | Heteronym / Semi-heteronym | Translator, poet; director of Ibis Press; author of a paper; author of the first phase of The Book of Disquiet |

| 13 | Gervasio Guedes | Heteronym / Para-heteronym | Author of the text "A Coroação de Jorge Quinto" |

| 14 | Alexander Search | Heteronym | Poet and short story writer |

| 15 | Charles James Search | Heteronym / Para-heteronym | Translator and essayist; brother of Alexander Search |

| 16 | Jean-Méluret of Seoul | Heteronym / Proto-heteronym | French poet and essayist |

| 17 | Rafael Baldaya | Heteronym | Astrologer; author of Tratado da Negação and Princípios de Metaphysica Esotérica |

| 18 | Barão de Teive | Heteronym | Prose writer; author of Educação do Stoica and Daphnis e Chloe |

| 19 | Charles Robert Anon | Heteronym / Semi-heteronym | Poet, philosopher and story writer |

| 20 | A. A. Crosse | Pseudonym / Proto-heteronym | Author and puzzle-solver |

| 21 | Thomas Crosse | Heteronym / Proto-heteronym | English epic character/occultist, popularized in Portuguese culture |

| 22 | I. I. Crosse | Heteronym / Para-heteronym | |

| 23 | David Merrick | Heteronym / Semi-heteronym | Poet, storyteller and playwright |

| 24 | Lucas Merrick | Heteronym / Para-heteronym | Short story writer; perhaps brother David Merrick |

| 25 | Pêro Botelho | Heteronym / Pseudonym | Short story writer and author of letters |

| 26 | Abilio Quaresma | Heteronym / Character / Meta-heteronym | Character inspired by Pêro Botelho and author of short detective stories |

| 27 | Inspector Guedes | Character / Meta-heteronym? | Character inspired by Pêro Botelho and author of short detective stories |

| 28 | Uncle Pork | Pseudonym / Character | Character inspired by Pêro Botelho and author of short detective stories |

| 29 | Frederick Wyatt | Alias / Heteronym | English poet and prose writer |

| 30 | Rev. Walter Wyatt | Character | Possibly brother of Frederick Wyatt |

| 31 | Alfred Wyatt | Character | Another brother of Frederick Wyatt and resident of Paris |

| 32 | Maria José | Heteronym / Proto-heteronym | Wrote and signed "A Carta da Corcunda para o Serralheiro" |

| 33 | Chevalier de Pas | Pseudonym / Proto-heteronym | Author of poems and letters |

| 34 | Efbeedee Pasha | Heteronym / Proto-heteronym | Author of humoristic stories |

| 35 | Faustino Antunes / A. Moreira | Heteronym / Pseudonym | Psychologist and author of Ensaio sobre a Intuição |

| 36 | Carlos Otto | Heteronym / Proto-heteronym | Poet and author of Tratado de Lucta Livre |

| 37 | Michael Otto | Pseudonym / Para-heteronym | Probably brother of Carlos Otto who was entrusted with the translation into English of Tratado de Lucta Livre |

| 38 | Sebastian Knight | Proto-heteronym / Alias | |

| 39 | Horace James Faber | Heteronym / Semi-heteronym | English short story writer and essayist |

| 40 | Navas | Heteronym / Para-heteronym | Translated Horace James Faber in Portuguese |

| 41 | Pantaleão | Heteronym / Proto-heteronym | Poet and prose writer |

| 42 | Torquato Fonseca Mendes da Cunha Rey | Heteronym / Meta-heteronym | Deceased author of a text Pantaleão decided to publish |

| 43 | Joaquim Moura Costa | Proto-heteronym / Semi-heteronym | Satirical poet; Republican activist; member of O Phosphoro |

| 44 | Sher Henay | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | Compiler and author of the preface of a sensationalist anthology in English |

| 45 | Anthony Gomes | Semi-heteronym / Character | Philosopher; author of "Historia Cómica do Affonso Çapateiro" |

| 46 | Professor Trochee | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | Author of an essay with humorous advice for young poets |

| 47 | Willyam Links Esk | Character | Signed a letter written in English on 13 April 1905 |

| 48 | António de Seabra | Pseudonym / Proto-heteronym | Literary critic |

| 49 | João Craveiro | Pseudonym / Proto-heteronym | Journalist; follower of Sidonio Pereira |

| 50 | Tagus | Pseudonym | Collaborator in Natal Mercury (Durban, South Africa) |

| 51 | Pipa Gomes | Draft heteronym | Collaborator in O Phosphoro |

| 52 | Ibis | Character / Pseudonym | Character from Pessoa's childhood accompanying him until the end of his life; also signed poems |

| 53 | Dr. Gaudencio Turnips | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | English-Portuguese journalist and humorist; director of O Palrador |

| 54 | Pip | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | Poet and author of humorous anecdotes; predecessor of Dr. Pancrácio |

| 55 | Dr. Pancrácio | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | Storyteller, poet and creator of charades |

| 56 | Luís António Congo | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | Collaborator in O Palrador; columnist and presenter of Eduardo Lança |

| 57 | Eduardo Lança | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | Luso-Brazilian poet |

| 58 | A. Francisco de Paula Angard | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | Collaborator in O Palrador; author of "Textos scientificos" |

| 59 | Pedro da Silva Salles / Zé Pad | Proto-heteronym / Alias | Author and director of the section of anecdotes at O Palrador |

| 60 | José Rodrigues do Valle / Scicio | Proto-heteronym / Alias | Collaborator in O Palrador; author of charades; literary manager |

| 61 | Dr. Caloiro | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | Collaborator in O Palrador; reporter and author of A pesca das pérolas |

| 62 | Adolph Moscow | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | Collaborator in O Palrador; novelist and author of Os Rapazes de Barrowby |

| 63 | Marvell Kisch | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | Author of a novel announced in O Palrador, called A Riqueza de um Doido |

| 64 | Gabriel Keene | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | Author of a novel announced in O Palrador, called Em Dias de Perigo |

| 65 | Sableton-Kay | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | Author of a novel announced in O Palrador, called A Lucta Aérea |

| 66 | Morris & Theodor | Pseudonym | Collaborator in O Palrador; author of charades |

| 67 | Diabo Azul | Pseudonym | Collaborator in O Palrador; author of charades |

| 68 | Parry | Pseudonym | Collaborator in O Palrador; author of charades |

| 69 | Gallião Pequeno | Pseudonym | Collaborator in O Palrador; author of charades |

| 70 | Urban Accursio | Alias | Collaborator in O Palrador; author of charades |

| 71 | Cecília | Pseudonym | Collaborator in O Palrador; author of charades |

| 72 | José Rasteiro | Proto-heteronym / Pseudonym | Collaborator in O Palrador; author of proverbs and riddles |

| 73 | Nympha Negra | Pseudonym | Collaborator in O Palrador; author of charades |

| 74 | Diniz da Silva | Pseudonym / Proto-heteronym | Author of the poem "Loucura"; collaborator in Europe |

| 75 | Herr Prosit | Pseudonym | Translator of El estudiante de Salamanca by José Espronceda |

| 76 | Henry More | Proto-heteronym | Author and prose writer |

| 77 | Wardour | Character? | Poet |

| 78 | J. M. Hyslop | Character? | Poet |

| 79 | Vadooisf ? | Character? | Poet |

| 80 | Nuno Reis | Pseudonym | Son of Ricardo Reis |

| 81 | João Caeiro | Character? | Son of Alberto Caeiro and Ana Taveira |

Alberto Caeiro

[edit]Alberto Caeiro was the first heteronym which Pessoa considered to be great or seminal. Through that heteronym, Pessoa wrote exclusively poetry. According to an anthology edited by Jerónimo Pizarro and Patricio Ferrari titled The Collected Works of Alberto Caeiro, "This imaginary author was a shepherd who spent most of his life in the countryside, had almost no education, and was ignorant of most literature."[76]

Critics note that Caeiro's poems demonstrate wide-eyed childlike wonder at nature. Octavio Paz, in translating his work, refers to him as an "innocent poet".[77] Specifically, Paz observes Caeiro's willingness to accept reality as such rather than attempting to dress it up in what other poets would consider to be aesthetic. Rather than using poetry as an interpretative and transformative device, Paz argues, Caeiro simply wrote poetry as such. In other words, Caiero's method is phenomenological as opposed to aesthetic.[78]

Such a philosophy makes Caeiro contrast greatly with his creator, Pessoa, who was deferential to modernism and thus interrogates the world around him rather than merely experience it. Pessoa regarded him as follows: "He sees things with the eyes only, not with the mind. He does not let any thoughts arise when he looks at a flower ... the only thing a stone tells him is that it has nothing at all to tell him ... this way of looking at a stone may be described as the totally unpoetic way of looking at it. The stupendous fact about Caeiro is that out of this sentiment, or rather, absence of sentiment, he makes poetry."[79]

The critic Jane M. Sheets notes that the creation of Caeiro was a necessary precursor to the later heteronyms to follow by providing a universalizing poetic vision from which others could be derived. While Caeiro was a short-lived heteronym in Pessoa's career, it established several tenets which would inevitably appear in the works of Campos, Reis, and Pessoa's own work.[80]

Ricardo Reis

[edit]

(5 issues edited by Pessoa and Ruy Vaz in 1924–1925), published poetry by Pessoa, Ricardo Reis, and Alberto Caeiro, as well as essays by Álvaro de Campos.

In a letter to William Bentley,[81] Pessoa wrote that "a knowledge of the language would be indispensable, for instance, to appraise the 'Odes' of Ricardo Reis, whose Portuguese would draw upon him the blessing of António Vieira, as his stile and diction that of Horace (he has been called, admirably I believe, 'a Greek Horace who writes in Portuguese')".[82]

Reis, both a character and a heteronym of Fernando Pessoa himself,[83] sums up his philosophy of life in his own words, admonishing, "See life from a distance. Never question it. There's nothing it can tell you." Like Caeiro, whom he admires, Reis defers from questioning life. He prides himself as a modern pagan who urges one to seize the day and accept fate with tranquility. "Wise is the one who does not seek. The seeker will find in all things the abyss, and doubt in himself."[84] In such sense, Reis shares essential affinities with Caeiro.

Believing in the Greek gods, yet living in a Christian Europe, Reis feels that his spiritual life is limited and true happiness cannot be attained. Such feeling—paired with his belief in Fate as a driving force for all that exists and thus disregarding freedom—leads to his epicureanist philosophy, which entails the avoidance of pain, defending that man should seek tranquility and calm above all else, avoiding emotional extremes.

Where Caeiro wrote freely and spontaneously, with joviality, of his basic, meaningless connection to the world, Reis writes in an austere, cerebral manner, with premeditated rhythm and structure and a particular attention to the correct use of the language when approaching his subjects of, as characterized by Richard Zenith, "the brevity of life, the vanity of wealth and struggle, the joy of simple pleasures, patience in time of trouble, and avoidance of extremes".

In his detached, intellectual approach, he is closer to Fernando Pessoa's constant rationalization, as such representing the orthonym's wish for measure and sobriety and a world free of troubles and respite, in stark contrast to Caeiro's spirit and style. As such, where Caeiro's predominant attitude is that of joviality, his sadness being accepted as natural ("My sadness is a comfort for it is natural and right."), Reis is marked by melancholy, saddened by the impermanence of all things.

Ricardo Reis is the main character of José Saramago's 1986 novel The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis.[85]

Álvaro de Campos

[edit]

Álvaro de Campos manifests, in a way, as a hyperbolic version of Pessoa himself. Of the three heteronyms he is the one who feels most strongly, his motto being 'to feel everything in every way.' 'The best way to travel,' he wrote, 'is to feel.' As such, his poetry is the most emotionally intense and varied, constantly juggling two fundamental impulses: on the one hand a feverish desire to be and feel everything and everyone, declaring that 'in every corner of my soul stands an altar to a different god' (alluding to Walt Whitman's desire to 'contain multitudes'), on the other, a wish for a state of isolation and a sense of nothingness.

As a result, his mood and principles varied between violent, dynamic exultation, as he fervently wishes to experience the entirety of the universe in himself, in all manners possible (a particularly distinctive trait in this state being his futuristic leanings, including the expression of great enthusiasm as to the meaning of city life and its components) and a state of nostalgic melancholy, where life is viewed as, essentially, empty.

One of the poet's constant preoccupations, as part of his dichotomous character, is that of identity: he does not know who he is, or rather, fails at achieving an ideal identity. Wanting to be everything, and inevitably failing, he despairs. Unlike Caeiro, who asks nothing of life, he asks too much. In his poetic meditation 'Tobacco Shop' he asks:

How should I know what I'll be, I who don't know what I am?

To be what I think? But I think of being so many things!

Summaries of selected works

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

Message

[edit]

Mensagem,[86] written in Portuguese, is a symbolist epic made up of 44 short poems organized in three parts or Cycles:[87]

The first, called "Brasão" (Coat-of-Arms), relates Portuguese historical protagonists to each of the fields and charges in the Portuguese coat of arms. The first two poems ("The castles" and "The escutcheons") draw inspiration from the material and spiritual natures of Portugal. Each of the remaining poems associates to each charge a historical personality. Ultimately they all lead to the Golden Age of Discovery.

The second Part, called "Mar Português" (Portuguese Sea), references the country's Age of Portuguese Exploration and to its seaborne Empire that ended with the death of King Sebastian at El-Ksar el Kebir (Alcácer-Quibir in Portuguese) in 1578. Pessoa brings the reader to the present as if he had woken up from a dream of the past, to fall in a dream of the future: he sees King Sebastian returning and still bent on accomplishing a Universal Empire.

The third Cycle, called "O Encoberto" ("The Hidden One"), refers to Pessoa's vision of a future world of peace and the Fifth Empire (which, according to Pessoa, is spiritual and not material, because if it were material England would already have achieved it). After the Age of Force (Vis), and Taedium (Otium) will come Science (understanding) through a reawakening of "The Hidden One", or "King Sebastian". The Hidden One represents the fulfillment of the destiny of mankind, designed by God since before Time, and the accomplishment of Portugal.

King Sebastian is very important, indeed he appears in all three parts of Mensagem. He represents the capacity of dreaming, and believing that it's possible to achieve dreams.

One of the most famous quotes from Mensagem is the first line from O Infante (belonging to the second Part), which is Deus quer, o homem sonha, a obra nasce (which translates roughly to "God wishes, man dreams, the work is born"). Another well-known quote from Mensagem is the first line from Ulysses, "O mito é o nada que é tudo" (a possible translation is "The myth is the nothing that is all"). This poem refers to Ulysses, king of Ithaca, as Lisbon's founder (recalling an ancient Greek myth).[88]

Literary essays

[edit]

In 1912, Fernando Pessoa wrote a set of essays (later collected as The New Portuguese Poetry) for the cultural journal A Águia (The Eagle), founded in Oporto, in December 1910, and run by the republican association Renascença Portuguesa.[89] In the first years of the Portuguese Republic, this cultural association was started by republican intellectuals led by the writer and poet Teixeira de Pascoaes, philosopher Leonardo Coimbra and historian Jaime Cortesão, aiming for the renewal of Portuguese culture through the aesthetic movement called Saudosismo.[a] Pessoa contributed to the journal A Águia with a series of papers: 'The new Portuguese Poetry Sociologically Considered' (nr. 4), 'Relapsing...' (nr. 5) and 'The Psychological Aspect of the new Portuguese Poetry' (nrs. 9,11 and 12). These writings were strongly encomiastic to saudosist literature, namely the poetry of Teixeira de Pascoaes and Mário Beirão. The articles disclose Pessoa as a connoisseur of modern European literature and an expert of recent literary trends. On the other hand, he does not care much for a methodology of analysis or problems in the history of ideas. He states his confidence that Portugal would soon produce a great poet – a super-Camões – pledged to make an important contribution for European culture, and indeed, for humanity.[90]

Philosophical essays

[edit]The philosophical notes of the young Pessoa, mostly written between 1905 and 1912, illustrate his debt to the history of philosophy more through commentators than through a first-hand protracted reading of the Classics, ancient or modern.[91] The issues he engages with pertain to every philosophical discipline and concern a large profusion of concepts, creating a vast semantic spectrum in texts whose length varies between half a dozen lines and half a dozen pages and whose density of analysis is extremely variable; simple paraphrasis, expression of assumptions and original speculation.

Pessoa sorted the philosophical systems thus:

- Relative Spiritualism and relative Materialism privilege "Spirit" or "Matter" as the main pole that organizes data around Experience.

- Absolute Spiritualist and Absolute Materialist "deny all objective reality to one of the elements of Experience".

- The materialistic Pantheism of Spinoza and the spiritualizing Pantheism of Malebranche, "admit that experience is a double manifestation of any thing that in its essence has no matter neither spirit".

- Considering both elements as an "illusory manifestation", of a transcendent and true and alone realities, there is Transcendentalism, inclined into matter with Schopenhauer, or into spirit, a position where Bergson could be emplaced.

- A terminal system "the limited and summit of metaphysics" would not radicalize – as poles of experience – one of the single categories: matter, relative, absolute, real, illusory, spirit. Instead, matching all categories, it takes contradiction as "the essence of the universe" and defends that "an affirmation is so more true insofar the more contradiction involves". The transcendent must be conceived beyond categories. There is one only and eternal example of it. It is that cathedral of thought -the philosophy of Hegel.

Such pantheist transcendentalism is used by Pessoa to define the project that "encompasses and exceeds all systems"; to characterize the new poetry of Saudosismo where the "typical contradiction of this system" occurs; to inquire of the particular social and political results of its adoption as the leading cultural paradigm; and, at last, he hints that metaphysics and religiosity strive "to find in everything a beyond".

Cultural references

[edit]Poetry from Fernando Pessoa appears in many films. For example, a quote from "Autopsychography" opens the Korean film The Cage (2017) by director Lior Shamriz.[92][93] The 1982 film Five and the Skin was based on Pessoa's Book of Disquiet.

The choral song "The Tower Bell in My Village" by Veljo Tormis (1978) bases on y Pessoa poetry.[94][95]

The novel Requiem: A Hallucination by Antonio Tabucchi, published in 1991, features the ghost of an unnamed Portuguese writer who is indicated to be Pessoa.[96]

The 2008 film The Night Fernando Pessoa Met Constantine Cavafy, directed by Stelios Haralambopoulos, focuses on a meeting between Constantine P. Cavafy and Pessoa on board a transatlantic ship.[97]

The 2024 film Cartas Telepáticas (Telepathic Letters), directed by Edgar Pêra explores the relationship between the ideas of Pessoa and H. P. Lovecraft, using AI to generate a film about a fictional correspondence between the two writers based on their existing writings.[98]

Nicolas Barral's 2024 comic book The Disquiet of Senhor Pessoa is about Pessoa's last days, from the perspective of a journalist tasked with writing his obituary in advance.[99]

The Australian band Augie March put Pessoa's 1918 poem "This" to music in their song of the same name, on the album Malagrotta (2024).

Works

[edit]- Antinous: a poem, Lisbon: Monteiro & Co., 1918 (16 p., 20 cm). Portugal: PURL.

- 35 Sonnets, Lisbon: Monteiro & Co., 1918 (20 pp., 20 cm). Portugal: PURL.

- English Poems, 2 vols. (vol. 1 part I – Antinous, part II – Inscriptions; vol. 2 part III – Epithalamium), Lisbon: Olisipo, 1921 (vol. 1, 20 pp.; vol. 2, 16 pp., 24 cm). Portugal: PURL.

- Selected Poems, tr. Edwin Honig, Swallow Press, 1971. ISBN B000XU4FE4

- Selected Poems, tr. Peter Rickard, University of Texas Press, 1972

- The Book of Disquiet (first published 1982; multiple translations and editions exist)

- Always Astonished: Selected Prose, translated by Edwin Honig, San Francisco, USA: City Lights Books, 1988, ISBN 978-0-87286-228-9

- Fernando Pessoa: Self-Analysis and Thirty Other Poems, tr. George Monteiro, Gavea-Brown Publications, 1989. ISBN 0-943722-14-4

- Message, tr. Jonathan Griffin, introduction by Helder Macedo, Menard Press, 1992. ISBN 1-905700-27-X

- The Anarchist Banker and Other Portuguese Stories. Carcanet Press, 1996. ISBN 978-1-8575420-6-6

- The Keeper of Sheep, bilingual edition, tr. Edwin Honig & Susan M. Brown, Sheep Meadow, 1997. ISBN 1-878818-45-7

- Poems of Fernando Pessoa, translated by Edwin Honig; Susan Brown, San Francisco, USA: City Lights Books, 1998, ISBN 978-0-87286-342-2

- Fernando Pessoa & Co: Selected Poems, tr. Richard Zenith, Grove Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8021-3627-3

- Selected Poems: with New Supplement tr. Jonathan Griffin, Penguin Classics; 2nd edition, 2000. ISBN 0-14-118433-7

- The Selected Prose of Fernando Pessoa, translated by Richard Zenith, New York, USA: Grove Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-8021-3914-6

- Sheep's Vigil by a Fervent Person: A Translation of Alberto Caeiro/Fernando Pessoa, tr. Erin Moure, House of Anansi, 2001. ISBN 0-88784-660-2

- The Education of the Stoic, tr. Richard Zenith, afterwords by Antonio Tabucchi and Richard Zenith, Exact Change, 2005. ISBN 1-878972-40-5

- A Little Larger Than the Entire Universe: Selected Poems, tr. Richard Zenith, Penguin Classics, 2006. ISBN 0-14-303955-5

- A Centenary Pessoa, tr. Keith Bosley & L. C. Taylor, foreword by Octavio Paz, Carcanet Press, 2006. ISBN 1-85754-724-1

- Selected English Poems, Exeter, UK: Shearsman Books, 2007, ISBN 978-1-905700-26-4, retrieved 28 July 2010

- The Collected Poems of Alberto Caeiro, translated by Chris Daniels, Exeter, UK: Shearsman Books, 2007, ISBN 978-1-905700-24-0, retrieved 28 July 2010

- Lisbon: What the Tourist Should See, Exeter, UK: Shearsman Books, 2008, ISBN 978-1-905700-25-7, archived from the original on 2 April 2011, retrieved 28 July 2010

- Collected Later Poems of Álvaro de Campos, 1928–1935, translated by Chris Daniels, Exeter, UK: Shearsman Books, 2009 [1928–35], ISBN 978-1-905700-25-7, retrieved 28 July 2010

- Forever Someone Else – selected poems – 2nd edition (enlarged), translated by Richard Zenith, Lisbon, Portugal: Assírio & Alvim, 2010 [2008], ISBN 978-972-37-1379-4, archived from the original on 14 January 2013

- Histórias de um Raciocinador e o ensaio "História Policial" (Tales of a Reasoner and the essay "Detective Story") bilingual edition, translated from the original writings in English, Ana Maria Freitas, edit & transl, Lisbon, Portugal: Assírio & Alvim, 2012, ISBN 978-972-0-79312-6, archived from the original on 14 January 2013

- Philosophical Essays: A Critical Edition. Edited with notes and introduction by Nuno Ribeiro. New York: Contra Mundum Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0-9836972-6-8

- The Transformation Book — or Book of Tasks. Edited with notes and introduction by Nuno Ribeiro and Cláudia Souza. New York: Contra Mundum Press, 2014.

- Un libro muy original | A Very Original Book [as Alexander Search]. Bilingual edition with notes by Natalia Jerez Quintero. Medellin: Tragaluz, 2014.

- The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro. Edited by Jerónimo Pizarro and Patricio Ferrari, translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari. New York City: New Directions, 2020.

- Writings on Art & Poetical Theory (2022). Edited with notes and introduction by Nuno Ribeiro and Cláudia Souza. New York: Contra Mundum Press, 2022. Second edition published by Columbia University Press in 2025.

- The Complete Works of Álvaro de Campos, translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari. New York City: New Directions, 2023.

See also

[edit]- Geração de Orpheu

- Heteronym

- Álvaro de Campos

- The Book of Disquiet

- The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis

- Portuguese poetry

- Dreams of Speaking

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Portuguese Republic was founded by the revolution of 5 October 1910, giving freedom of association and publishing.

References

[edit]- ^ "Pessoa". Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ Ciuraru, Carmela. "Fernando Pessoa & His Heteronyms". Poetry Society of America. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Zenith, Richard (2008). Fotobiografias Século XX: Fernando Pessoa. Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores.

- ^ Tóibín, Colm (12 August 2021). "I haven't been I". London Review of Books. Vol. 43, no. 16. ISSN 0260-9592. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Letter to British Journal of Astrology, W. Foulsham & Co., 61, Fleet Street, London, E.C., 8 February 1918. In Pessoa, Fernando (1999). Correspondência 1905–1922, ed. Manuela Parreira da Silva. Lisboa: Assírio & Alvim, p. 258, ISBN 978-85-7164-916-3.

- ^ a b Zenith, Richard (2021). Pessoa: A Biography. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. ISBN 9781324090779.

- ^ Monteiro, George (2000). Fernando Pessoa and Nineteenth-century Anglo-American Literature. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-3270-9.

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando; Zenith, Richard (2006). A little larger than the entire universe: selected poems. Penguin classics. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-303955-6. OCLC 62282634.

- ^ Monteiro, Maria da Encarnação (1961), Incidências Inglesas na Poesia de Fernando Pessoa, Coimbra: author ed.

- ^ Jennings, H. D. (1984), Os Dois Exilios, Porto: Centro de Estudos Pessoanos

- ^ Clifford E. Geerdts, letter to Dr. Faustino Antunes, 10 April 1907. In Pessoa, Fernando (2003). Escritos Autobiográficos, Automáticos e de Reflexão Pessoal, ed. Richard Zenith. Lisboa: Assírio & Alvim, pp. 394–398.

- ^ Ferro, António Joaquim Tavares, ed. (1915), Orpheu Nº1 Revista Trimestral de Literatura (in Portuguese)

- ^ de Campos, Alvaro; Cisneiros, Violante; Guimarães, Eduardo; de Oliveira Sousa Leal, Raul; Vaz Pinto Azevedo Coutinho de Lima, Ângelo; de Montalvor, Luís; Pessoa, Fernando; de Sá-Carneiro, Mário, António Joaquim Tavares Ferro (ed.), Orpheu, Project Gutenberg

- ^ "Fernando Pessoa - an icon of Portuguese modernism – Go to Portugal - Portugal guides". 8 May 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Ibe name "ibis" has a very long literary tradition: the elegiac poem Ibis by Ovid was inspired in the lost poem of the same title by Callimachus.

- ^ Zenith, Richard (2008), Fernando Pessoa, Fotobiografias do Século XX (in Portuguese), Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores, p. 78.

- ^ Ferro, António, ed. (January–March 1915), Orpheu (in Portuguese), Lisboa: Orpheu, Lda..

- ^ Saraiva, Arnaldo (ed.), Orpheu (in Portuguese), Lisboa: Edições Ática.

- ^ Ruy Vaz, Fernando Pessoa, ed. (October 1924 – February 1925), Athena (in Portuguese), Lisboa: Imprensa Libanio da Silva, archived from the original on 14 January 2013.

- ^ Zenith, Richard (2008), Fotobiografias do Século XX: Fernando Pessoa. Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Guerreiro, Ricardina (2004), De Luto por Existir: a melancolia de Bernardo Soares à luz de Walter Benjamin. Lisboa: Assírio & Alvim, p. 159.

- ^ Sousa, João Rui de (2010), Fernando Pessoa Empregado de Escritório, 2nd ed. Lisboa: Assírio & Alvim.

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando (2002), The Book of Disquiet, London: Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-118304-6.

- ^ Dias, Marina Tavares (2002), Lisboa nos Passos de Pessoa: uma cidade revisitada através da vida e da obra do poeta [Lisbon in Pessoa's footsteps: a Lisbon tour through the life and poetry of Fernando Pessoa], Lisboa: Quimera.

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando (2006) [1992], Lisboa: o que o turista deve ver (in Portuguese and English) (3rd ed.), Lisboa: Livros Horizonte, archived from the original on 16 August 2011, retrieved 18 July 2011

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando (2008), Lisbon: what the tourist should see, Exeter, UK: Shearsman Books, archived from the original on 2 April 2011, retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ Boto, António (2010), The Songs of António Botto, U of Minnesota Press, ISBN 978-0-8166-7100-7. Translated by Fernando Pessoa.

- ^ Published in a serial in the Portuguese Journal Ilustração, from 1 January 1926, without a reference to the translator, as usual.

- ^ Athena nr. 3, December 1924, pp. 89–102 and nr. 5, February 1925, pp. 173–184.

- ^ Fernando Pessoa, Obra Poética, Rio de Janeiro: José Aguilar Editora, 1965.

- ^ A Biblioteca Internacional de Obras Célebres, volumes VI pp. 2807-2809, VII pp. 3534-3535, XX pp. 10215‑10218.

- ^ Athena nr. 1, October 1924, pp. 27–29 and nr. 4, January 1925, pp. 161–164.

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando (1967), Páginas de Estética e de Teoria e Crítica Literárias, Lisbon: Ática.

- ^

A Voz do Silêncio (The Voice of Silence) at the Portuguese National Library.

Besant, Annie (1915), Os Ideaes da Theosophia, Lisboa: Livraria Clássica Editora.

Leadbeater, C. W. (1915), Compêndio de Theosophia, Lisboa: Livraria Clássica Editora.

Leadbeater, C. W. (1916), Auxiliares Invisíveis, Lisboa: Livraria Clássica Editora.

Leadbeater, C. W. (1916), A Clarividência, Lisboa: Livraria Clássica Editora.

Blavatsky, Helena (1916), A Voz do Silêncio, Lisboa: Livraria Clássica Editora.

Collins, Mabel (1916), Luz Sobre o Caminho e o Karma, Lisboa: Livraria Clássica Editora.

- ^ Ana Luísa Pinheiro Nogueira, his mother's sister was also his godmother, a widow with two children, Maria and Mário. She traveled to Switzerland in November 1914, with her daughter and son-in-law, recently married.

- ^ a b c Pessoa, Fernando (1999), Correspondência 1905–1922, Lisbon: Assírio & Alvim, ISBN 978-85-7164-916-3.

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando, "Carta à Tia Anica - 24 Jun. 1916", Arquivo Pessoa (in Portuguese), MultiPessoa, retrieved 8 November 2020

- ^ Cardoso, Paulo (2011), Fernando Pessoa, cartas astrológicas, Lisbon: Bertrand editora, ISBN 978-972-25-2261-8.

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando (1917), Pessoa é solicitado para escrever um volume teórico de introdução ao Neopaganismo Português (in Portuguese), MultiPessoa, retrieved 13 February 2018,

Eu sou um pagão decadente, do tempo do outono da Beleza; do sonolecer [?] da limpidez antiga, místico intelectual da raça triste dos neoplatónicos da Alexandria. Como eles creio, e absolutamente creio, nos Deuses, na sua agência e na sua existência real e materialmente superior. Como eles creio nos semi-deuses, os homens que o esforço e a (...) ergueram ao sólio dos imortais; porque, como disse Píndaro, «a raça dos deuses e dos homens é uma só». Como eles creio que acima de tudo, pessoa impassível, causa imóvel e convicta [?], paira o Destino, superior ao bem e ao mal, estranho à Beleza e à Fealdade, além da Verdade e da Mentira. Mas não creio que entre o Destino e os Deuses haja só o oceano turvo [...] o céu mudo da Noite eterna. Creio, como os neoplatónicos, no Intermediário Intelectual, Logos na linguagem dos filósofos, Cristo (depois) na mitologia cristã.

- ^ The magical world of Fernando Pessoa, Nthposition, archived from the original on 8 September 2017, retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ Presença nr. 33 (July–October 1931).

- ^ PASI, Marco (2002), "The Influence of Aleister Crowley on Fernando Pessoa's Esoteric Writings", The Magical Link, 9 (5): 4–11.

- ^ Fernando Pessoa, letter to Rider & C., Paternoster Row, London, E.C.4., 20 October 1933. In Pessoa, Fernando. Correspondência 1923–1935, ed. Manuela Parreira da Silva. Lisboa: Assírio & Alvim, 1999, pp. 311–312.

- ^ Martin Lüdke, "Ein moderner Hüter der Dinge; Die Entdeckung des großen Portugiesen geht weiter: Fernando Pessoa hat in der Poesie Alberto Caeiros seinen Meister gesehen", ("A modern guardian of things; The discovery of the great Portuguese continues: Fernando Pessoa saw its master in the poetry of Alberto Caeiro"), Frankfurter Rundschau, 18 August 2004. "Caeiro unterläuft die Unterscheidung zwischen dem Schein und dem, was etwa "Denkerge-danken" hinter ihm ausmachen wollen. Die Dinge, wie er sie sieht, sind als was sie scheinen. Sein Pan-Deismus basiert auf einer Ding-Metaphysik, die in der modernen Dichtung des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts noch Schule machen sollte." Translation: "Caeiro interposes the distinction between the light and what "philosopher thoughts" want to constitute behind him. The things, as he sees them, are as they seem. His pandeism is based on a metaphysical thing, which should still become a school of thought under the modern seal of the twentieth century."

- ^ Zenith, Richard (2008), Fotobiografias do Século XX: Fernando Pessoa, Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Terlinden, Anne (1990), Fernando Pessoa, the bilingual Portuguese poet: A Critical Study of "The Mad Fidler", Bruxelles: Facultés Universitaires Saint-Louis, ISBN 978-2-8028-0075-0.

- ^ Antinous, at the Portuguese National Libraryf.

- ^ "35 sonnets", Biblioteca Nacional Digital, Lisbon, 1918, retrieved 4 February 2023

- ^ The Times Literary Supplement, 19 September 1918. Athenaeum, January 1919.

- ^ Contemporanea, May–July 1922, pp. 121–126.

- ^ a b Barreto, Jose (2008), "Salazar and the New State in the Writings of Fernando Pessoa", Portuguese Studies, 24 (2): 169, doi:10.1353/port.2008.0011, S2CID 245848666

- ^ Serrão (int. and org.), Joel (1980), Fernando Pessoa, Ultimatum e Páginas de Sociologia Política, Lisboa: Ática.

- ^ Barreto, Jose (2008), "Salazar and the New State in the Writings of Fernando Pessoa", Portuguese Studies, 24 (2): 170–172, doi:10.1353/port.2008.0011, S2CID 245848666

- ^ Sadlier, Darlene J. (Winter 1997), "Nationalism, Modernity, and the Formation of Fernando Pessoa's Aesthetic", Luso-Brazilian Review, 34 (2): 110

- ^ Barreto, Jose (2008), "Salazar and the New State in the Writings of Fernando Pessoa", Portuguese Studies, 24 (2): 170–173, doi:10.1353/port.2008.0011, S2CID 245848666

- ^ Darlene Joy Sadlier An introduction to Fernando Pessoa: modernism and the paradoxes of authorship, University Press of Florida, 1998, pp. 44–7.

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando, "Uma Apologia Da Maçonaria Portuguesa", maconaria.net (in European Portuguese), retrieved 4 February 2023

- ^ Barreto, José (2009), "Fernando Pessoa e a invasão da Abissínia pela Itália fascista", Análise Social, XLIV (193): 693–718

- ^ a b c "Fernando Pessoa & His Heteronyms", Poetry Society of America, retrieved 4 February 2023

- ^ R. W. Howes (1983), "Fernando Pessoa, Poet, Publisher, and Translator" (PDF), British Library Journal, p. 162, archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2017, retrieved 4 February 2023

- ^ "Will the real Pessoa step forward?", The Independent, 30 May 1995, retrieved 4 February 2023

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando (1 December 2007), Fernando Pessoa & Co.: Selected Poems, Open Road + Grove/Atlantic, p. 163, ISBN 978-0-8021-9851-8

- ^ Ferreira, Francisco Manuel da Fonseca, O Hábito de Beber no Contexto Existencial e Poético de Femando Pessoa. Oporto: Laboratorios Bial, 1995.

- ^ Cruz, Ireneu (1997), "A propósito da morte de Fernando Pessoa. O diagnóstico diferencial da cólica hepática." [The death of Fernando Pessoa. The differential diagnosis of liver colic.], Acta Med Port (in Portuguese), 10 (2-3 (Feb/Mar)): 221–224, PMID 9235856

- ^ Caption to photo 32, opposite page 115, in: Lisboa, E. and Taylor, L. C., eds; with an introduction by Paz, O. (1995), A Centenary Pessoa, Manchester: Carcanet Press Limited.

- ^ Mosteiro dos Jerónimos Archived 2 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Fernando Pessoa

- ^ Monteiro, George (Spring 2016), ""Letter to Adolfo Casais Monteiro" translation from "Imaginary poets in a real world"" (PDF), Pessoa Plural (9): 301, retrieved 4 February 2023

- ^ Castro, Ivo, "O corpus de 'O Guardador de Rebanhos' depositado na Biblioteca Nacional", Separata da Revista da Biblioteca Nacional, vol. 2, n.º 1, 1982, pp. 47-61.

- ^ a b Zenith, Richard (22 July 2021). "The Heteronymous Identities of Fernando Pessoa". Literary Hub. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ MODERN!SMO.pt. "Pancrácio". modernismo.pt (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth David (2016). "Pessoa's Voluptuous Skepticism" (PDF). Pessoa Plural. 10.

- ^ "Sublunary Editions | Independent publisher". sublunaryeditions.com. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ The Book of Disquiet, tr. Richard Zenith, Penguin classics, 2003.

- ^ Letter to Adolfo Casais Monteiro, 13 January 1935.

- ^ "Letter to Adolfo Casais Monteiro", 13 January 1935, in Pessoa, Fernando (2003), The Book of Disquiet, tr. Richard Zenith. London: Penguin classics, p. 474.

- ^ "The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro by Fernando Pessoa | New Directions". www.ndbooks.com. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ ""Octavio Paz: Paths Towards the Untranslatable" by Christian Elguera - Latin American Literature Today". 21 February 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Paz, Octavio (1983), "El Desconocido de Si Mismo: Fernando Pessoa", in Los Signos en Rotacion y Otros Ensayos, Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando; Zenith, Richard (1998), Fernando Pessoa & Co. : selected poems (1st ed.), New York: Grove Press, p. 40, ISBN 0802116280, OCLC 38055974

- ^ Sheets, Jane M., Fernando Pessoa as Anti-Poet: Alberto Caeiro, in Bulletin of Hispanic Studies, Vol. XLVI, Nr. 1, January 1969, pp. 39–47.

- ^ This letter, to the director of the journal Portugal, was written on 31 October 1924, to announce Pessoa's art journal Athena.

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando (1999), Correspondência 1923–1935, ed. Manuela Parreira da Silva. Lisboa: Assírio & Alvim, p.53, ISBN 972-37-0531-1.

- ^ Jones, Marilyn Scarantino (1 January 1977), "Pessoa's Poetic Coterie: Three Heteronyms and an Orthonym", Luso-Brazilian Review, 14 (2): 254–262, JSTOR 3513064

- ^ Reis, Ricardo (pseud.) (16 June 1927), "Enquanto eu vir o sol luzir nas folhas", Arquivo Pessoa (in Portuguese), retrieved 12 September 2021,

Sábio deveras o que não procura, / Que, procurando, achara o abismo em tudo / E a dúvida em si mesmo.

- ^ "The Year Of The Death Of Ricardo Reis". HarperCollins Publishers. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando (2016), Freitas, Eduardo (ed.), A Mensagem: Editado Por Eduardo Filipe Freitas (in Portuguese), CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, ISBN 978-1-535-19909-4

- ^ Message, Tr. by Jonathan Griffin, Exeter: Shearsman Books, 2007.

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando (1934). Mensagem. Lisbon: Parceria A.M. Pereira. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ Martins, Fernando Cabral (coord.) (2008). Dicionário de Fernando Pessoa e do Modernismo Português. Alfragide: Editorial Caminho.

- ^ Pessoa, Fernando (1993). Textos de Crítica e de Intervenção. Lisboa: Edições Ática.

- ^ Zenith, Richard (2021), Pessoa: A Biography, New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, ISBN 9781324090779.

- ^ "『魅惑の貞操具「The Cage」』".

- ^ "Between False Realities" (PDF). liorshamriz.com.

- ^ "The Tower Bell in My Village".

- ^ "Tornikell minu külas / The Tower Bell in My Village".

- ^ Staff writer (16 May 1994). "Requiem: A Hallucination". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 22 February 2025.

- ^ "The Night Fernando Pessoa Met Constantine Cavafy".

- ^ "Review: Telepathic Letters". 14 August 2024.

- ^ Roure, Benjamin (21 January 2025). "L'Intranquille Monsieur Pessoa". BoDoï (in French). Retrieved 22 February 2025.

Further reading

[edit]Books

[edit]- Gray de Castro, Mariana, ed. Fernando Pessoa's Modernity Without Frontiers: Influences, Dialogues, Responses. Vol. 320. Tamesis Books, 2013.

- Green, J. C. R. Fernando Pessoa: The Genesis of the Heteronyms. Isle of Skye: Aquila, 1982.

- Jackson, Kenneth David. Adverse Genres in Fernando Pessoa. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Jennings, Hubert D. and Carlos Pittella. Fernando Pessoa, the Poet with Many Faces: A biography and anthology. Providence, RI: Gavea-Brown, 2018.

- Klobucka, Anna and Mark Sabine, (eds.). Embodying Pessoa: Corporeality, Gender, Sexuality. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007.

- Kotowicz, Zbigniew. Fernando Pessoa: Voices of a Nomadic Soul. London: Menard, 1996.

- Lancastre, Maria José de and Antonio Tabucchi. Fernando Pessoa: Photographic Documentation and Caption.Paris : Hazan, 1997.

- Lisboa, Eugénio and L. C. Taylor. A Centenary Pessoa. Manchester, England: Carcanet, 1995.

- McGuirk, Bernard. Three Persons on One: A Centenary Tribute to Fernando Pessoa. Nottingham, England: University of Nottingham, 1988.

- Monteiro, George. Fernando Pessoa and Nineteenth-century Anglo-American Literature. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2000.

- Monteiro, George. The Man Who Never Was: Essays on Fernando Pessoa. Providence, RI: Gávea-Brown, 1982.

- Monteiro, George. The Presence of Pessoa: English, American, and Southern African Literary Responses. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1998.

- Pessoa's Alberto Caeiro. Dartmouth, Mass.: University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, 2000.

- Santos, Maria Irene Ramalho Sousa. Atlantic Poets: Fernando Pessoa's Turn in Anglo-American Modernism. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2003.

- Sadlier, Darlene J. An Introduction to Fernando Pessoa, Literary Modernist. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1998.

- Terlinden-Villepin, Anne. Fernando Pessoa: The Bilingual Portuguese Poet. Brussels: Facultés universitaires Saint-Louis, 1990.

- Zenith, Richard. Pessoa: A Biography. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2021, ISBN 9781324090779. Also published as Pessoa: An Experimental Life. London: Allen Lane, 2021.

Articles

[edit]- Anderson, R. N., "The Static Drama of Pessoa, Fernando", Hispanofila (104): 89–97 (January 1992).

- Bloom, Harold, "Fernando Pessoa" in Genius: A Mosaic of One Hundred Exemplary Creative Minds. New York: Warner Books, 2002.

- Brown, S. M., "The Whitman Pessoa Connection", Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 9 (1): 1–14 SUM 1991.

- Bunyan, D, "The South-African Pessoa: Fernando 20th Century Portuguese Poet", English in Africa 14 (1), May 1987, pp. 67–105.

- Cruz, Anne J., "Masked Rhetoric: Contextuality in Fernando Pessoa's Poems", Romance Notes, vol. XXIX, no. 1 (Fall, 1988), pp. 55–60.

- De Castro, Mariana, "Oscar Wilde, Fernando Pessoa, and the art of lying", Portuguese Studies 22 (2): 219, 2006. JSTOR

- Dyer, Geoff, "Heteronyms", The New Statesman, vol. 4 (6 December 1991), p. 46.

- Eberstadt, Fernanda, "Proud of His Obscurity", The New York Times Book Review, vol. 96, (1 September 1991), p. 26.

- Ferrari, Patricio. "Proverbs in Fernando Pessoa's works", Proverbium, vol. 31, pp. 235–244.

- Guyer, Leland, "Fernando Pessoa and the Cubist Perspective", Hispania, vol. 70, no. 1 (March 1987), pp. 73–78.

- Haberly, David T., "Fernando Pessoa: Overview" in Lesley Henderson (ed.), Reference Guide to World Literature, 2nd ed. St. James Press, 1995.

- Hicks, J., "The Fascist imaginary in Pessoa and Pirandello", Centennial Review 42 (2): 309–332 SPR 1998.

- Hollander, John, "Quadrophenia", The New Republic, 7 September 1987, pp. 33–6.

- Howes, R. W., "Pessoa, Fernando, Poet, Publisher, and Translator", British Library Journal 9 (2): 161–170 1983.

- Jennings, Hubert D., "In Search of Fernando Pessoa" Contrast 47 – South African Quarterly, vol. 12 no. 3 (June 1979).

- Lopes J. M., "Cubism and intersectionism in Fernando Pessoa's 'Chuva Obliqua", Texte (15–16),1994, pp. 63–95.

- Mahr, G., "Pessoa, life narrative, and the dissociative process" in Biography 21 (1) Winter 1998, pp. 25–35.

- McNeill, Pods, "The aesthetic of fragmentation and the use of personae in the poetry of Fernando Pessoa and W. B. Yeats", Portuguese Studies 19: 110–121 2003.

- Monteiro, George, "The Song of the Reaper-Pessoa and Wordsworth", Portuguese Studies 5, 1989, pp. 71–80.

- Muldoon P., "In the hall of mirrors: 'Autopsychography' by Fernando Pessoa", New England Review 23 (4), Fall 2002, pp. 38–52.

- Pasi, Marco, "September 1930, Lisbon: Aleister Crowley’s lost diary of his Portuguese trip" Pessoa Plural, no. 1 (Spring 2012), pp. 253–283.

- Pasi, Marco & Ferrari, Patricio, "Fernando Pessoa and Aleister Crowley: New discoveries and a new analysis of the documents in the Gerald Yorke Collection", Pessoa Plural, no. 1 (Spring 2012), pp. 284–313.

- Phillips, A., "Pessoa's Appearances" in Promises, Promises, London: Faber and Faber Limited, 2000, pp. 113–124.

- Polito, Robert, "Fernando Pessoa" Bomb Magazine, Issue #65, 1 October 1998.

- Ribeiro, A. S., "A tradition of empire: Fernando Pessoa and Germany", Portuguese Studies 21: 201–209, 2005

- Riccardi, Mattia, "Dionysus or Apollo? The heteronym Antonio Mora as moment of Nietzsche's reception by Pessoa", Portuguese Studies 23 (1), 109, 2007.

- Rosenthal, David H., "Unpredictable Passions", The New York Times Book Review, 13 December 1987, p. 32.

- Seabra, J.A., "Pessoa, Fernando Portuguese Modernist Poet", Europe 62 (660): 41–53 1984.

- Severino, Alexandrino E., "Fernando Pessoa's Legacy: The Presença and After", World Literature Today, vol. 53, no. 1 (Winter, 1979), pp. 5–9.

- Severino, Alexandrino E., "Pessoa, Fernando – A Modern Lusiad", Hispania 67 (1): 52–60 1984.

- Severino, Alexandrino E., "Was Pessoa Ever in South Africa?" Archived 14 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine Hispania Archived 17 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, vol. 74, no. 3 (September 1991).

- Sheets, Jane M., "Fernando Pessoa as Anti-Poet: Alberto Caeiro", Bulletin of Hispanic Studies, vol. XLVI, no. 1 (January 1969), pp. 39–47.

- Simon, Ed, "The Poet Is a Man Who Feigns" JSTOR Daily, September 20, 2023.

- Sousa, Ronald W., "The Structure of Pessoa's Mensagem", Bulletin of Hispanic Studies, vol. LIX, no. 1, January 1982, pp. 58–66.

- Steiner, George, "A man of many parts", The Observer, 3 June 2001.

- Suarez, Jose, "Fernando Pessoa's acknowledged involvement with the occult", Hispania 90 (2): (May 2007), 245–252.

- Wood, Michael, "Mod and Great" The New York Review of Books, vol. XIX, no. 4 (21 September 1972), pp. 19–22.

- Wood, Michael, "The Sorcerer's Apprentice" The New York Review of Books (24 October 1991).

- Zenith, Richard, "Pessoa, Fernando and the Theater of his Self", Performing Arts Journal (44), May 1993, pp. 47–49.

Videos

[edit]- Professor David Jackson: Adverse Genres in Fernando Pessoa 10:20. Yale University, 11/12/2009.

Professor Jacksons research interests focus on Portuguese and Brazilian Literatures; modernist and inter-arts literature; Portuguese culture in Asia; and ethnomusicology. He has written and edited several books and other publications. We talk with Professor Jackson about his forthcoming book, Adverse Genres in Fernando Pessoa.

18 November 2013, at the Woodberry Poetry Room, Harvard University.

As a part of our Omniglot Seminar series, Portuguese translator Richard Zenith read from his translations of Luís de Camões, Fernando Pessoa and Carlos Drummond de Andrade. He compared his experiences translating archaic vs. contemporary linguistic registers, highly formal poetry vs. free verse, and European vs. Brazilian Portuguese. And he discussed the unique challenge of translating (and researching a biography of) a poet such as Pessoa, with alter egos that wrote in radically different styles.

- Fernando Pessoa: An Englishly Portuguese, Endlessly Multiple Poet 1:04:12. Library of Congress, 22/04/2015.