France–United Kingdom relations

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 36 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 36 min

| |

United Kingdom |

France |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of the United Kingdom, Paris | Embassy of France, London |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Menna Rawlings | Ambassador Hélène Tréheux-Duchêne |

The historical ties between France and the United Kingdom, and the countries preceding them, are long and complex, including conquest, wars, and alliances at various points in history. The Roman era saw both areas largely conquered by Rome, whose fortifications largely remain in both countries to this day. The Norman conquest of England in 1066, followed by the long domination of the Plantagenet dynasty of French origin, decisively shaped the English language and led to early conflict between the two nations.

Throughout the Middle Ages and into the Early Modern Period, France and England were often bitter rivals, with both nations' monarchs claiming control over France and France routinely allying against England with their other rival Scotland until the Union of the Crowns. The historical rivalry between the two nations was seeded in the Capetian-Plantagenet rivalry over the French holdings of the Plantagenets in France. After the French victory in the Hundred Years' War, England would never again establish a foothold in French territory.

Rivalry continued with many Anglo-French wars. The last major conflict between the two was the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815), in which coalitions of European powers, financed by London, fought a series of wars against the French First Republic, the First French Empire and its client states, culminating in the defeat of Napoleon in 1815. For several decades the peace was uneasy with fear of French invasion in 1859 and during the later rivalry for African colonies. Nevertheless, peace has generally prevailed since Napoleon I, and friendly ties between the two were formally established with the 1904 Entente Cordiale, and the British and French were allied against Germany in both World War I and World War II; in the latter conflict, British armies helped to liberate occupied France from Nazi Germany.

France and the UK were key partners in the West during the Cold War, consistently supporting liberal democracy and capitalism. They were founding members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) defence alliance and are permanent members of the UN Security Council. France has been a member of the European Union (EU), and its predecessors, since creation as the European Economic Community in 1957. In the 1960s, relations deteriorated due to French President Charles de Gaulle's concerns over the special relationship between the UK and the United States. He repeatedly vetoed British entry into the European Communities, the predecessor to the EU, and withdrew France from NATO integrated command, arguing the alliance was too heavily dominated by the United States.

In 1973, following de Gaulle's death, the UK entered the European Communities and in 2009 France returned to an active role in NATO under the presidency of Nicolas Sarkozy. Since then, the two countries have experienced a close relationship, especially on defence and foreign policy issues; however they disagreed on several other matters, most notably the direction of the European Union.[1] The United Kingdom left the European Union on 31 January 2020, following the referendum held on 23 June 2016, on Brexit.[2] Relations have since deteriorated, with disagreements surrounding Brexit and the English Channel migrant crisis.[3][4][5]

In the 21st century, France and Britain, though they have chosen different paths and share many overlooked similarities (with roughly the same population, economic size, commitment to democracy, diplomatic clout, and as heads of former global empires.[6][7][8][9]), are often still referred to as "historic rivals",[10] with a perceived ever-lasting competition.[11] French author José-Alain Fralon characterised the relationship between the countries by describing the British as "our most dear enemies".

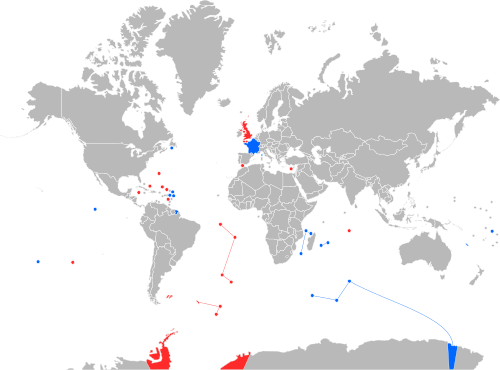

It is estimated that about 350,000 French people live in the UK, with approximately 200,000 Britons living in France.[12] Both countries are members of the Council of Europe and NATO. France is a European Union member and the United Kingdom is a former European Union member.

History

[edit]

1945–1956

[edit]The UK and France became close in the aftermath of World War II, as both feared the Americans would withdraw from Europe leaving them vulnerable to the Soviet Union's expanding communist bloc. The UK was successful in strongly advocating that France be given a zone of occupied Germany. Both states were amongst the five Permanent Members of the new UN Security Council, where they commonly collaborated. However, France was bitter when the United States and Britain refused to share atomic secrets with it. An American operation to use air strikes (including the potential use of tactical nuclear weapons) during the climax of the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in May 1954 was cancelled because of opposition by the British.[13][14] The upshot was France developed its own nuclear weapons and delivery systems.[15]

The Cold War began in 1947, as the United States, with strong British support, announced the Truman Doctrine to contain Communist expansion and provided military and economic aid to Greece and Turkey. Despite its large pro-Soviet Communist Party, France joined the Allies. The first move was the Franco-British alliance realised in the Dunkirk Treaty in March 1947.[16]

Suez Crisis

[edit]In 1956, the Suez Canal, previously owned by an Anglo-French company, was nationalised by the Egyptian government. The British and the French were both strongly committed to taking the canal back by force.[17] President Eisenhower and the Soviet Union demanded there be no invasion and both imposed heavy pressure to reverse the invasion when it came. The relations between Britain and France were not entirely harmonious, as the French did not inform the British about the involvement of Israel until very close to the commencement of military operations.[18] The failure in Suez convinced Paris it needed its own nuclear weapons.[19][20]

Common Market

[edit]Immediately after the Suez crisis Anglo-French relations started to sour again, and only since the last decades of the 20th century have they improved towards the peak they achieved between 1900 and 1940.

Shortly after 1956, France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg formed what would become the European Economic Community and later the European Union, but rejected British requests for membership. In particular, President Charles de Gaulle's attempts to exclude the British from European affairs during France's early Fifth Republic are now seen by many in Britain as a betrayal of the strong bond between the countries, and Anthony Eden's exclusion of France from the Commonwealth is seen in a similar light in France. The French partly feared that were the British to join the EEC they would attempt to dominate it.

Over the years, the UK and France have often taken diverging courses within the European Community. British policy has favoured an expansion of the Community and free trade while France has advocated a closer political union and restricting membership of the Community to a core of Western European states.

De Gaulle

[edit]In 1958, with France mired in a seemingly unwinnable war in Algeria, Charles de Gaulle returned to power in France. He created the Fifth French Republic, ending the post-war parliamentary system and replacing it with a strong Presidency, which became dominated by his followers—the Gaullists. De Gaulle made ambitious changes to French foreign policy—first ending the war in Algeria, and then withdrawing France from the NATO command structure. The latter move was primarily symbolic, but NATO headquarters moved to Brussels and French generals had a much lesser role.[21][22]

French policy blocking British entry into the European Economic Community (EEC) was primarily motivated by political rather than economic considerations. In 1967, as in 1961–63, de Gaulle was determined to preserve France's dominance within the EEC, which was the foundation of the nation's international stature. His policy was to preserve the Community of Six while barring Britain. Although France succeeded in excluding Britain in the short term, in the longer term the French had to adjust their stance on enlargement in order to retain influence. De Gaulle feared that letting Britain into the European Community would open the way for "Anglo-Saxon" (i.e., US and UK) influence to overwhelm the France-West Germany coalition that was now dominant. On 14 January 1963, de Gaulle announced that France would veto Britain's entry into the Common Market.[23]

Since 1969

[edit]

When de Gaulle resigned in 1969, a new French government under Georges Pompidou was prepared to open a more friendly dialogue with Britain. He felt that in the economic crises of the 1970s Europe needed Britain. Pompidou welcomed British membership of the EEC, opening the way for the United Kingdom to join it in 1973.[25]

The two countries' relationship was strained significantly in the lead-up to the 2003 War in Iraq. Britain and its American ally strongly advocated the use of force to remove Saddam Hussein, while France (with China, Russia, and other nations) strongly opposed such action, with French President Jacques Chirac threatening to veto any resolution proposed to the UN Security Council. However, despite such differences Chirac and then British Prime Minister Tony Blair maintained a fairly close relationship during their years in office even after the Iraq War started.[26] Both states asserted the importance of the Entente Cordiale alliance, and the role it had played during the 20th century.

Sarkozy presidency

[edit]Following his election in 2007, President Nicolas Sarkozy attempted to forge closer relations between France and the United Kingdom: in March 2008, Prime Minister Gordon Brown said that "there has never been greater cooperation between France and Britain as there is now".[27] Sarkozy also urged both countries to "overcome our long-standing rivalries and build together a future that will be stronger because we will be together".[28] He also said "If we want to change Europe my dear British friends—and we Frenchmen do wish to change Europe—we need you inside Europe to help us do so, not standing on the outside."[29] On 26 March 2008, Sarkozy had the privilege of giving a speech to both British Houses of Parliament, where he called for a "brotherhood" between the two countries[30] and stated that "France will never forget Britain's war sacrifice" during World War II.[31]

In March 2008, Sarkozy made a state visit to Britain, promising closer cooperation between the two countries' governments in the future.[32]

Hollande presidency

[edit]

The final months towards the end of François Hollande's tenure as president saw the UK vote to leave the EU. His response to the result was "I profoundly regret this decision for the United Kingdom and for Europe, but the choice is theirs and we have to respect it."[33]

The then-Economy Minister and current President Emmanuel Macron accused the UK of taking the EU "hostage" with a referendum called to solve a domestic political problem of eurosceptics and that "the failure of the British government [has opened up] the possibility of the crumbling of Europe."[34]

In contrast, the vote was welcomed by Eurosceptic political leaders and presidential candidates Marine Le Pen and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan as a victory for "freedom".[35][36]

Macron presidency

[edit]

In the aftermath of Brexit, fishing disputes, notably the 2021 Jersey dispute, have caused turbulence in relations between the two countries.[37]

In May 2021, France threatened to cut off electricity to the British Channel Island of Jersey in a fight over post-Brexit fishing rights.[38][39]

In August 2021, Tensions emerged between the countries after the announcement of the AUKUS agreement between the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia.[40]

In October 2021, the UK Foreign Office summoned the French ambassador over "threats" made by French officials against Jersey.[41] In November, France threatened to ban UK fishing vessels from French ports.[42]

In November 2021, relations became more stagnant after the French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian claimed that British Prime Minister Boris Johnson is a "populist who uses all elements at his disposal to blame others for problems he faces internally".[43] A few days later, after 27 migrants drowned in the English Channel, Prime Minister Boris Johnson tweeted a letter that was sent to French President Emmanuel Macron which had irritated him due to the letter being made public on Twitter.[44] The French Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin cancelled a proposed meeting with British Home Secretary Priti Patel over the migrant crossings due to the row over the letter.[45]

On 6 March 2022, French Interior Minister Gerald Darmanin urged Britain to do more to assist Ukrainian refugees trapped in the French port of Calais, claiming that British officials were turning them away owing to a lack of permits or papers.[46]

On 25 August 2022, Liz Truss, the expected candidate for Prime Minister from the Conservative Party was asked if she sees Macron as a friend or a rival. Truss hesitated and replied that "The jury's out. But if I become prime minister, I'll judge him on deeds, not words". This answer brought a sharp reaction on behalf of the Labour Party when David Lammy, who serves as the party's foreign affairs spokesman, said in response that "the fact that she chose to unnecessarily insult one of our closest allies shows a lack of judgement, and that lack of capacity is a terrible and worrying thing." Macron himself responded that "the British people, Britain itself, are a friendly, strong nation and our ally, regardless of the identity of its leaders, and sometimes despite its leaders or the small mistakes they make in their attempt to impress the audience". He added: "If we, France and Britain, are unable to say whether we are friends or enemies - and the term is not neutral - then we are on the way to serious problems. If I were to be asked this question, I would not hesitate for a second - Britain is France's friend."[47]

A bilateral summit in March 2023 between President Emmanuel Macron and Prime Minister Rishi Sunak marked a shift towards collaboration on energy, migration, and security.[48]

The election of Prime Minister Keir Starmer in 2024 further strengthened ties, with both governments issuing a joint statement reaffirming commitments to European security and climate action.

Symbolic events, such as King Charles III's 2023 state visit to France have further reinforced bilateral ties.[49]

Defence cooperation

[edit]The two nations have a post WWII record of working together on international security measures, as was seen in the Suez Crisis and Falklands War. In her 2020 book, Johns Hopkins University SAIS political scientist Alice Pannier writes that there is a growing "special relationship" between France and the UK in terms of defence cooperation.[50]

On 2 November 2010, France and the UK signed two defence co-operation treaties. They provide for the sharing of aircraft carriers, a 10,000-strong joint reaction force, a common nuclear simulation centre in France, a common nuclear research centre in the UK, sharing air-refuelling tankers and joint training.[51][52]

Their post-colonial entanglements have given them a more outward focus than the other countries of Europe, leading them to work together on issues such as the Libyan Civil War.[53]

Commerce

[edit]France is the United Kingdom's third-biggest export market after the United States and Germany. Exports to France rose 14.3% from £16.542 billion in 2010 to £18.905 billion in 2011, overtaking exports to the Netherlands. Over the same period, French exports to Britain rose 5.5% from £18.133 billion to £19.138 billion.[54]

The British Foreign & Commonwealth Office estimates that 19.3 million British citizens, roughly a third of the entire population, visit France each year.[55] In 2018, they reported 13 million trips.[56] In 2012, the French were the biggest visitors to the UK (12%, 3,787,000) and the second-biggest tourist spenders in Britain (8%, £1.513 billion).[57]

Education

[edit]The Entente Cordiale Scholarship scheme is a selective Franco-British scholarship scheme which was announced on 30 October 1995 by British Prime Minister John Major and French President Jacques Chirac at an Anglo-French summit in London.[58]

It provides funding for British and French students to study for one academic year on the other side of the Channel. The scheme is administered by the French embassy in London for British students,[59] and by the British Council in France and the UK embassy in Paris for French students.[60][61] Funding is provided by the private sector and foundations. The scheme aims to favour mutual understanding and to promote exchanges between the British and French leaders of tomorrow.

The programme was initiated by Sir Christopher Mallaby, British ambassador to France between 1993 and 1996.[62]

The sciences

[edit]

The Concorde supersonic commercial aircraft was developed under an international treaty between the UK and France in 1962, and commenced flying in 1969. It was a technological success but a financial disaster and was closed down after a runway crash in 2000 and fully ended flights in 2003.[63]

Cultural relations

[edit]Over the centuries, French and British art and culture have been heavily influenced by each other.[64] During the 19th century, numerous French artists moved to the United Kingdom, which many of them settling in London. These artists included Charles-François Daubigny, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, James Tissot and Alfred Sisley. This exodus would prove to have a significant influence on the development of impressionism in Britain.[65]

Sexual euphemisms with no link to France, such as French kissing, or French letter for a condom, are used in British English slang.[66] While in French slang, the term le vice anglais refers to either BDSM or homosexuality.[67] French classical music has always been popular in Britain. British popular music is in turn popular in France. English literature, in particular the works of Agatha Christie and William Shakespeare, has been immensely popular in France. French artist Eugène Delacroix based many of his paintings on scenes from Shakespeare's plays. In turn, French writers such as Molière, Voltaire and Victor Hugo have been translated numerous times into English. In general, most of the more popular books in either language are translated into the other. The same can be applied for adaptations of said books; some of which have achieved considerable critical and commercial success in both territories. For example, the West End production of the musical adaptation of Hugo’s novel, Les Misérables premiered in 1985 and is still running to this very day.[citation needed]

Language

[edit]

The first foreign language most commonly taught in schools in Britain is French, and the first foreign language most commonly taught in schools in France is English; those are also the languages perceived as "most useful to learn" in both countries. Queen Elizabeth II of the UK was fluent in French and did not require an interpreter when travelling to French-language countries.[68][69] French is a substantial minority language and immigrant language in the United Kingdom, with over 100,000 French-born people in the UK. According to a 2006 European Commission report, 23% of UK residents are able to carry on a conversation in French and 39% of French residents are able to carry on a conversation in English.[70] French is also an official language in both Jersey and Guernsey. Both use French to some degree, mostly in an administrative or ceremonial capacity. Jersey Legal French is the standardised variety used in Jersey. However, Norman (in its local forms, Guernésiais and Jèrriais) is the historical vernacular of the islands.

Both languages have influenced each other throughout the years. According to different sources, more than 50% of all English words have a French origin, and today many French expressions have entered the English language as well.[71] The term Franglais, a portmanteau combining the French words "français" and "anglais", refers to the combination of French and English (mostly in the UK) or the use of English words and nouns of Anglo-Saxon roots in French (in France).

Modern and Middle English reflect a mixture of Oïl and Old English lexicons after the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, when a Norman-speaking aristocracy took control of a population whose mother tongue was Germanic in origin. Due to the intertwined histories of England and continental possessions of the English Crown, many formal and legal words in Modern English have French roots. For example, buy and sell are of Germanic origin, while purchase and vend are from Old French.

Sports

[edit]

In the sport of rugby union there is a rivalry between England and France. Both countries compete in the Six Nations Championship and the Rugby World Cup. England has the edge in both tournaments, having the most outright wins in the Six Nations (and its previous version the Five Nations), and most recently knocking the French team out of the 2003 and 2007 World Cups at the semi-final stage, although France knocked England out of the 2011 Rugby World Cup with a convincing score in their quarter final match. Though rugby is originally a British sport, French rugby has developed to such an extent that the English and French teams are now stiff competitors, with neither side greatly superior to the other. While English influences spread rugby union at an early stage to Scotland, Wales and Ireland, as well as the Commonwealth realms, French influence spread the sport outside the commonwealth, to Italy, Argentina, Romania and Georgia.

The influence of French players and coaches on British football has been increasing in recent years and is often cited as an example of Anglo-French cooperation. In particular the Premier League club Arsenal has become known for its Anglo-French connection due to a heavy influx of French players since the advent of French manager Arsène Wenger in 1996. In March 2008 their Emirates stadium was chosen as the venue for a meeting during a state visit by the French President precisely for this reason.[72]

Many people blamed the then French President Jacques Chirac for contributing to Paris' loss to London in its bid for the 2012 Summer Olympics after he made derogatory remarks about British cuisine and saying that "only Finnish food is worse". The IOC committee which would ultimately decide to give the games to London (by four votes) had two members from Finland.[73]

Transport

[edit]Ferries

[edit]The busiest seaway in the world,[74] the English Channel, connects ports in Great Britain such as Dover, Newhaven, Poole, Weymouth, Portsmouth and Plymouth to ports such as Roscoff, Calais, Boulogne, Dunkerque, Dieppe, Cherbourg-Octeville, Caen, St Malo and Le Havre in mainland France. Companies such as Brittany Ferries, P&O Ferries, DFDS Seaways and LD Lines operate ferry services across the Channel.

In addition, there are ferries across the Anguilla Channel between Blowing Point, Anguilla (a British Overseas Territory) and Marigot, Saint Martin (an overseas collectivity of France). [75]

Channel Tunnel

[edit]

The Channel Tunnel (French: Le tunnel sous la Manche; also referred to as the Chunnel)[76][77] is a 50.5-kilometre (31.4 mi) undersea rail tunnel (linking Folkestone, Kent, in the United Kingdom with Coquelles, Pas-de-Calais, near the city of Calais in northern France) beneath the English Channel at the Strait of Dover. Ideas for a cross-Channel fixed link appeared as early as 1802,[78][79] but British political and press pressure over compromised national security stalled attempts to construct a tunnel.[80] The eventual successful project, organised by Eurotunnel, began construction in 1988 and was opened by British Queen Elizabeth II and French President François Mitterrand in a ceremony held in Calais on 6 May 1994. The same year the American Society of Civil Engineers elected the Channel Tunnel as one of the seven modern Wonders of the World.[81]

Flights

[edit]11,675,910 passengers in 2008 travelled on flights between the United Kingdom and France.[82]

Twin cities and towns

[edit]France has the most twin cities and towns in the United Kingdom.[citation needed]

Aberdeen and

Aberdeen and  Clermont-Ferrand, Puy-de-Dôme

Clermont-Ferrand, Puy-de-Dôme Andover, Hampshire and

Andover, Hampshire and  Redon, Ille-et-Vilaine

Redon, Ille-et-Vilaine Angmering, West Sussex and

Angmering, West Sussex and  Ouistreham, Calvados

Ouistreham, Calvados Anstruther, Fife and

Anstruther, Fife and  Bapaume, Pas-de-Calais

Bapaume, Pas-de-Calais Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire and

Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire and  Bourg-en-Bresse, Ain

Bourg-en-Bresse, Ain Aylsham, Norfolk and

Aylsham, Norfolk and  La Chaussée-Saint-Victor, Loir-et-Cher

La Chaussée-Saint-Victor, Loir-et-Cher Barnet, London and

Barnet, London and  Le Raincy, Seine-Saint-Denis

Le Raincy, Seine-Saint-Denis Barrow upon Soar, Leicestershire and

Barrow upon Soar, Leicestershire and  Marans, Charente-Maritime

Marans, Charente-Maritime Basildon, Essex and

Basildon, Essex and  Meaux, Seine-et-Marne

Meaux, Seine-et-Marne Basingstoke, Hampshire and

Basingstoke, Hampshire and  Alençon, Orne

Alençon, Orne Bath, Somerset and

Bath, Somerset and  Aix-en-Provence, Bouches-du-Rhône

Aix-en-Provence, Bouches-du-Rhône Beaminster, Dorset and

Beaminster, Dorset and  Saint-James, Manche

Saint-James, Manche Beccles, Suffolk and

Beccles, Suffolk and  Petit-Couronne, Seine-Maritime

Petit-Couronne, Seine-Maritime Birmingham, West Midlands and

Birmingham, West Midlands and  Lyon, Metropolitan Lyon

Lyon, Metropolitan Lyon Blandford Forum, Dorset and

Blandford Forum, Dorset and  Mortain, Manche

Mortain, Manche Bolton, Greater Manchester and

Bolton, Greater Manchester and  Le Mans, Sarthe

Le Mans, Sarthe Bourne, Lincolnshire and

Bourne, Lincolnshire and  Doudeville, Seine-Maritime

Doudeville, Seine-Maritime Bridport, Dorset and

Bridport, Dorset and  Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue, Manche

Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue, Manche Bristol, City of Bristol and

Bristol, City of Bristol and  Bordeaux, Gironde

Bordeaux, Gironde Bury, Greater Manchester and

Bury, Greater Manchester and  Angoulême, Charente

Angoulême, Charente Camberley, Surrey and

Camberley, Surrey and  Sucy-en-Brie, Val-de-Marne

Sucy-en-Brie, Val-de-Marne Canterbury, Kent and

Canterbury, Kent and  Reims, Marne

Reims, Marne Cardiff and

Cardiff and  Nantes, Loire-Atlantique

Nantes, Loire-Atlantique Chelmsford, Essex and

Chelmsford, Essex and  Annonay, Ardèche

Annonay, Ardèche Cheltenham, Gloucestershire and

Cheltenham, Gloucestershire and  Annecy, Haute-Savoie

Annecy, Haute-Savoie Chester, Cheshire and

Chester, Cheshire and  Sens, Yonne

Sens, Yonne Chichester, West Sussex and

Chichester, West Sussex and  Chartres, Eure-et-Loir

Chartres, Eure-et-Loir Chippenham, Wiltshire and

Chippenham, Wiltshire and  La Flèche, Sarthe

La Flèche, Sarthe Chipping Ongar, Essex and

Chipping Ongar, Essex and  Cerizay, Deux-Sèvres

Cerizay, Deux-Sèvres Christchurch, Dorset and

Christchurch, Dorset and  Saint-Lô, Manche

Saint-Lô, Manche Cockermouth, Cumbria and

Cockermouth, Cumbria and  Marvejols, Lozère

Marvejols, Lozère Coleraine and

Coleraine and  La Roche Sur Yon

La Roche Sur Yon Colchester, Essex and

Colchester, Essex and  Avignon, Vaucluse

Avignon, Vaucluse Congleton, Cheshire and

Congleton, Cheshire and  Trappes, Yvelines

Trappes, Yvelines Cowbridge, Vale of Glamorgan and

Cowbridge, Vale of Glamorgan and  Clisson, Pays de la Loire

Clisson, Pays de la Loire Cowes, Isle of Wight and

Cowes, Isle of Wight and  Deauville, Calvados

Deauville, Calvados Crewe, Cheshire and

Crewe, Cheshire and  Mâcon, Saône-et-Loire

Mâcon, Saône-et-Loire Devizes, Wiltshire and

Devizes, Wiltshire and  Mayenne, Pays de la Loire[83]

Mayenne, Pays de la Loire[83] Dorchester, Dorset and

Dorchester, Dorset and  Bayeux, Calvados

Bayeux, Calvados Dover, Kent and

Dover, Kent and  Calais, Pas-de-Calais

Calais, Pas-de-Calais Droylsden, Tameside and

Droylsden, Tameside and  Villemomble, Seine-Saint-Denis

Villemomble, Seine-Saint-Denis Dukinfield, Cheshire and

Dukinfield, Cheshire and  Champagnole, Jura

Champagnole, Jura Dundee and

Dundee and  Orléans, Loiret

Orléans, Loiret Ealing, London and

Ealing, London and  Marcq-en-Barœul, Nord

Marcq-en-Barœul, Nord East Preston, West Sussex and

East Preston, West Sussex and  Brou, Eure-et-Loir

Brou, Eure-et-Loir Edinburgh and

Edinburgh and  Nice, Alpes-Maritimes

Nice, Alpes-Maritimes Elmbridge, Surrey and

Elmbridge, Surrey and  Rueil-Malmaison, Hauts-de-Seine

Rueil-Malmaison, Hauts-de-Seine Epsom, Surrey and

Epsom, Surrey and  Chantilly, Oise

Chantilly, Oise Exeter, Devon and

Exeter, Devon and  Rennes, Ille-et-Vilaine

Rennes, Ille-et-Vilaine Exmouth, Devon and

Exmouth, Devon and  Dinan, Côtes-d'Armor

Dinan, Côtes-d'Armor Fareham, Hampshire, and

Fareham, Hampshire, and  Vannes, Morbihan

Vannes, Morbihan Ferndown, Dorset and

Ferndown, Dorset and  Segré, Maine-et-Loire

Segré, Maine-et-Loire Farnborough, Hampshire and

Farnborough, Hampshire and  Meudon, Hauts-de-Seine

Meudon, Hauts-de-Seine Folkestone, Kent and

Folkestone, Kent and  Boulogne-sur-Mer, Pas-de-Calais

Boulogne-sur-Mer, Pas-de-Calais Glasgow and

Glasgow and  Marseille, Bouches-du-Rhône

Marseille, Bouches-du-Rhône Gloucester, Gloucestershire and

Gloucester, Gloucestershire and  Metz, Moselle

Metz, Moselle Godalming, Surrey and

Godalming, Surrey and  Joigny, Yonne

Joigny, Yonne Hailsham, East Sussex and

Hailsham, East Sussex and  Gournay-en-Bray, Seine-Maritime

Gournay-en-Bray, Seine-Maritime Hammersmith and Fulham, London and

Hammersmith and Fulham, London and  Boulogne-Billancourt, Hauts-de-Seine

Boulogne-Billancourt, Hauts-de-Seine Harrogate, Yorkshire and

Harrogate, Yorkshire and  Luchon, Haute-Garonne

Luchon, Haute-Garonne Harrold, Bedfordshire and

Harrold, Bedfordshire and  Sainte-Pazanne, Loire-Atlantique

Sainte-Pazanne, Loire-Atlantique Harrow, London and

Harrow, London and  Douai, Nord

Douai, Nord Hastings, East Sussex and

Hastings, East Sussex and  Béthune, Pas-de-Calais

Béthune, Pas-de-Calais Havering, London and

Havering, London and  Hesdin, Pas-de-Calais

Hesdin, Pas-de-Calais Hereford, Herefordshire and

Hereford, Herefordshire and  Vierzon, Cher

Vierzon, Cher Herne Bay, Kent and

Herne Bay, Kent and  Wimereux, Pas-de-Calais

Wimereux, Pas-de-Calais Hillingdon, London and

Hillingdon, London and  Mantes-la-Jolie, Yvelines

Mantes-la-Jolie, Yvelines Hitchin, Hertfordshire and

Hitchin, Hertfordshire and  Nuits-Saint-Georges, Côte-d'Or

Nuits-Saint-Georges, Côte-d'Or Horsham, West Sussex and

Horsham, West Sussex and  Saint-Maixent-l'Ecole, Deux-Sèvres

Saint-Maixent-l'Ecole, Deux-Sèvres Hounslow, London and

Hounslow, London and  Issy-les-Moulineaux, Hauts-de-Seine

Issy-les-Moulineaux, Hauts-de-Seine Inverness and

Inverness and  Saint-Valery-en-Caux, Seine-Maritime

Saint-Valery-en-Caux, Seine-Maritime Ipswich, Suffolk and

Ipswich, Suffolk and  Arras, Pas-de-Calais

Arras, Pas-de-Calais Kensington and Chelsea, London and

Kensington and Chelsea, London and  Cannes, Alpes-Maritimes

Cannes, Alpes-Maritimes Leeds, Yorkshire and

Leeds, Yorkshire and  Lille, Nord

Lille, Nord Leicester and

Leicester and  Strasbourg, Bas-Rhin

Strasbourg, Bas-Rhin Lewisham, London and

Lewisham, London and  Antony, Hauts-de-Seine

Antony, Hauts-de-Seine Lichfield, Staffordshire and

Lichfield, Staffordshire and  Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon, Lyon Metropolis

Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon, Lyon Metropolis Littlehampton, West Sussex and

Littlehampton, West Sussex and  Chennevières-sur-Marne, Val-de-Marne

Chennevières-sur-Marne, Val-de-Marne Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire and

Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire and  Le Conquet, Finistère

Le Conquet, Finistère Llanelli, Carmarthenshire and

Llanelli, Carmarthenshire and  Agen, Lot-et-Garonne

Agen, Lot-et-Garonne London and

London and  Paris (this is not a twinning, since Paris is twinned only with Rome, but they are partner cities)

Paris (this is not a twinning, since Paris is twinned only with Rome, but they are partner cities) Loughborough, Leicestershire and

Loughborough, Leicestershire and  Épinal, Vosges

Épinal, Vosges Maidenhead, Berkshire and

Maidenhead, Berkshire and  Saint-Cloud, Hauts-de-Seine

Saint-Cloud, Hauts-de-Seine Maidstone, Kent and

Maidstone, Kent and  Beauvais, Oise

Beauvais, Oise Merthyr Tydfil, Merthyr Tydfil and

Merthyr Tydfil, Merthyr Tydfil and  Clichy, Hauts-de-Seine

Clichy, Hauts-de-Seine Middlesbrough, Yorkshire and

Middlesbrough, Yorkshire and  Dunkirk, Nord

Dunkirk, Nord Newcastle upon Tyne and

Newcastle upon Tyne and  Nancy, Meurthe-et-Moselle

Nancy, Meurthe-et-Moselle Newhaven, East Sussex and

Newhaven, East Sussex and  La Chapelle-Saint-Mesmin, Loiret

La Chapelle-Saint-Mesmin, Loiret Northampton, Northamptonshire and

Northampton, Northamptonshire and  Poitiers, Vienne

Poitiers, Vienne Norwich, Norfolk and

Norwich, Norfolk and  Rouen, Seine-Maritime

Rouen, Seine-Maritime Oxford, Oxfordshire and

Oxford, Oxfordshire and  Grenoble, Isère

Grenoble, Isère Perth and

Perth and  Cognac, Charente

Cognac, Charente Plymouth, Devon and

Plymouth, Devon and  Brest, Finistère

Brest, Finistère Portsmouth, Hampshire and

Portsmouth, Hampshire and  Caen, Calvados

Caen, Calvados Poole, Dorset and

Poole, Dorset and  Cherbourg-Octeville, Manche

Cherbourg-Octeville, Manche Preston, Lancashire and

Preston, Lancashire and  Nîmes, Gard

Nîmes, Gard Ramsgate, Kent and

Ramsgate, Kent and  Conflans-Sainte-Honorine, Yvelines

Conflans-Sainte-Honorine, Yvelines Reigate, Surrey and

Reigate, Surrey and  Brunoy, Essonne

Brunoy, Essonne Richmond upon Thames, London and

Richmond upon Thames, London and  Fontainebleau, Seine-et-Marne

Fontainebleau, Seine-et-Marne Rochdale, Greater Manchester and

Rochdale, Greater Manchester and  Tourcoing, Nord

Tourcoing, Nord Rotherham, Yorkshire and

Rotherham, Yorkshire and  Saint-Quentin, Aisne

Saint-Quentin, Aisne Royston, Hertfordshire and

Royston, Hertfordshire and  La Loupe, Eure-et-Loir

La Loupe, Eure-et-Loir Borough of Runnymede, Surrey and

Borough of Runnymede, Surrey and  Joinville-le-Pont, Val-de-Marne

Joinville-le-Pont, Val-de-Marne Salford, Greater Manchester and

Salford, Greater Manchester and  Clermont-Ferrand, Puy-de-Dôme

Clermont-Ferrand, Puy-de-Dôme Salisbury, Wiltshire and

Salisbury, Wiltshire and  Saintes, Charente-Maritime

Saintes, Charente-Maritime Sawbridgeworth, Hertfordshire and

Sawbridgeworth, Hertfordshire and  Bry-sur-Marne, Val-de-Marne

Bry-sur-Marne, Val-de-Marne Selby, Yorkshire and

Selby, Yorkshire and  Carentan, Manche

Carentan, Manche Sherborne, Dorset and

Sherborne, Dorset and  Granville, Manche

Granville, Manche City of Southampton, Hampshire and

City of Southampton, Hampshire and  Le Havre, Seine-Maritime

Le Havre, Seine-Maritime Southborough, Kent and

Southborough, Kent and  Lambersart, Nord

Lambersart, Nord Spelthorne, Surrey and

Spelthorne, Surrey and  Melun, Seine-et-Marne

Melun, Seine-et-Marne St Albans, Hertfordshire and

St Albans, Hertfordshire and  Nevers, Nièvre

Nevers, Nièvre Stalybridge, Tameside and

Stalybridge, Tameside and  Armentières, Nord

Armentières, Nord Stevenage, Hertfordshire and

Stevenage, Hertfordshire and  Autun, Saône-et-Loire

Autun, Saône-et-Loire Stockport, Greater Manchester and

Stockport, Greater Manchester and  Béziers, Hérault

Béziers, Hérault Sturminster Newton, Dorset and

Sturminster Newton, Dorset and  Montebourg, Manche

Montebourg, Manche Sunderland, Tyne & Wear and

Sunderland, Tyne & Wear and  Saint-Nazaire, Loire-Atlantique

Saint-Nazaire, Loire-Atlantique Sutton, London and

Sutton, London and  Gagny, Seine-Saint-Denis

Gagny, Seine-Saint-Denis Taunton, Somerset and

Taunton, Somerset and  Lisieux, Calvados

Lisieux, Calvados Truro, Cornwall and

Truro, Cornwall and  Morlaix, Finistère

Morlaix, Finistère Vale of White Horse, Oxfordshire and

Vale of White Horse, Oxfordshire and  Colmar, Haut-Rhin

Colmar, Haut-Rhin Verwood, Dorset and

Verwood, Dorset and  Champtoceaux, Maine-et-Loire

Champtoceaux, Maine-et-Loire Waltham Forest, London and

Waltham Forest, London and  Saint-Mandé, Val-de-Marne

Saint-Mandé, Val-de-Marne Ware, Hertfordshire and

Ware, Hertfordshire and  Cormeilles-en-Parisis, Val d'Oise

Cormeilles-en-Parisis, Val d'Oise Wareham, Dorset and

Wareham, Dorset and  Conches-en-Ouche, Eure

Conches-en-Ouche, Eure Watford, Hertfordshire and

Watford, Hertfordshire and  Nanterre, Hauts-de-Seine

Nanterre, Hauts-de-Seine Wellington, Shropshire and

Wellington, Shropshire and  Châtenay-Malabry, Hauts-de-Seine

Châtenay-Malabry, Hauts-de-Seine Wembury, Devonshire and

Wembury, Devonshire and  Locmaria-Plouzané, Finistère

Locmaria-Plouzané, Finistère Wetherby, Yorkshire and

Wetherby, Yorkshire and  Privas, Ardèche

Privas, Ardèche Weymouth and Portland, Dorset and

Weymouth and Portland, Dorset and  Louviers, Eure

Louviers, Eure Whitstable, Kent and

Whitstable, Kent and  Dainville, Pas-de-Calais

Dainville, Pas-de-Calais Wigan, Greater Manchester and

Wigan, Greater Manchester and  Angers, Maine-et-Loire

Angers, Maine-et-Loire Wimborne Minster, Dorset and

Wimborne Minster, Dorset and  Valognes, Manche

Valognes, Manche Winchester, Hampshire and

Winchester, Hampshire and  Laon, Aisne

Laon, Aisne Windsor, Berkshire and

Windsor, Berkshire and  Neuilly-sur-Seine, Hauts-de-Seine

Neuilly-sur-Seine, Hauts-de-Seine Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside and

Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside and  Lorient, Morbihan and Gennevilliers, Hauts-de-Seine

Lorient, Morbihan and Gennevilliers, Hauts-de-Seine Woking, Surrey and

Woking, Surrey and  Le Plessis-Robinson, Hauts-de-Seine

Le Plessis-Robinson, Hauts-de-Seine York, Yorkshire and

York, Yorkshire and  Dijon, Côte-d'Or

Dijon, Côte-d'Or

There are lists of twinnings (including those to towns in other countries) at List of twin towns and sister cities in France and at List of twin towns and sister cities in the United Kingdom.

Resident diplomatic missions

[edit]- France has an embassy in London and a consulate-general in Edinburgh.[84]

- The United Kingdom has an embassy in Paris and consulates in Bordeaux and Marseille and a trade office in Lyon.[85]

-

Embassy of France in London

-

Consulate-General of France in Edinburgh

-

Embassy of the United Kingdom in Paris

See also

[edit]- Angevin Empire

- Anglo-French War (disambiguation)

- History of French foreign relations

- Auld Alliance, between France and Scotland

- Common Security and Defence Policy

- Embassy of the United Kingdom, Paris

- English claims to the French throne

- Entente cordiale

- Entente Cordiale Scholarships

- Franco-British Union

- French migration to the United Kingdom

- Hundred Years' War

- List of British French

- List of ambassadors from the Kingdom of England to France (up to 1707)

- List of ambassadors of Great Britain to France (from 1707 to 1800).

- List of ambassadors of the United Kingdom to France (since 1800)

- List of Ambassadors of France to the United Kingdom (since 1800)

- Military history of England

- Military history of France

- Perfidious Albion

- Second Hundred Years' War

- SEPECAT Jaguar

- Triple Entente

- 1983 France–United Kingdom Maritime Boundary Convention

- 1996 France–United Kingdom Maritime Delimitation Agreements

- EU–UK relations

- European Union–NATO relations

- France–UK border

- English Channel migrant crossings (2018–present)

References

[edit]- ^ Britain and France: the impossible, indispensable relationship , The Economist, 1 Dec 2011

- ^ "The UK's EU referendum: All you need to know – BBC News". BBC News. 21 May 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ "The state of France's relationship with Britain". The Economist. 27 November 2021.

- ^ "'Total loss of confidence': Franco-British relations plumb new depths". The Guardian. 8 October 2021.

- ^ Manning, David (3 December 2021). "Britain needs to reset relations with France — here's how". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022.

- ^ France is becoming the new Britain, The Financial Times, March 2, 2023: "The countries are twins: two absurdly over-centralised former empires of 67mn people, forever struggling with deindustrialisation, where the past overhangs the present like a shroud."

- ^ Why Britain and France Hate Each Other, The Atlantic, September 24, 2021: "[...] far from being diametrically opposed, France and Britain are more similar than perhaps any other two countries on Earth. Not only in terms of population, wealth, imperial past, global reach, and democratic tradition, but the deeper stuff too: the sense of exceptionalism, fear of decline, instinct for national independence, desire for respect, and angst over the growing power of others, whether that be the United States, Germany, or China. London and Paris may have chosen different strategies—and there is nothing to say that both are equally meritorious—but the parallels between these two nations are obvious."

- ^ 'Whereas the French always believe they are sliding into some catastrophe, the English are complacent', Le Monde, July 29, 2022: "On the face of it, the UK and France are twins: 67 million inhabitants each, absurdly over-centralised, with almost identical GDP and lost imperial grandeur. Yet the two countries have taken different paths."

- ^ The real special relationship – Britain and France have more in common than either does with a third country, The Financial Times, May 12, 2023: "To an eerie degree, France and Britain are alike in population (67mn) and output ($3tn). Manufacturing is the same 9 per cent share of their economies. Their armed forces are comparable. Both built and lost extra-European empires and now have about the same weight in world affairs. One joined the European project from the start, one tarried and ultimately quit, but neither believed the nation state and hard power were forms of Oldthink."

- ^ Economies of Britain and France have more similarities than differences, The Guardian, 5 January 2014

- ^ "The two countries are forever comparing one against the other.[...]", Britain-France ties: How cordial is the entente?, BBC News, 30 January 2014

- ^ (in French) Royaume-Uni Archived 17 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine – France Diplomacie

- ^ Kowert, Paul (2002), Groupthink or deadlock: when do leaders learn from their advisors? (illustrated ed.), SUNY Press, pp. 67–68, ISBN 978-0-7914-5249-3

- ^ Tucker, Spencer (1999), Vietnam (illustrated ed.), Routledge, p. 76, ISBN 978-1-85728-922-0

- ^ Peter K. Parides, "The Halban Affair and British Atomic Diplomacy at the End of the Second World War." Diplomacy & Statecraft 23.4 (2012): 619–635.

- ^ Sean Greenwood, "Return to Dunkirk: The origins of the Anglo‐French treaty of March 1947." Journal of Strategic Studies 6.4 (1983): 49–65.

- ^ Turner p.186

- ^ Turner p.267

- ^ Wilfred L. Kohl, French nuclear diplomacy (Princeton University Press, 2015).

- ^ Jacques E.C. Hymans, "Why Do States Acquire Nuclear Weapons? Comparing the Cases of India and France." in Nuclear India in the Twenty-First Century (2002). 139–160. online

- ^ Philip G. Cerny, The Politics of Grandeur: Ideological Aspects of de Gaulle's Foreign Policy (1980).

- ^ W.W. Kulski, De Gaulle and the World: The Foreign Policy of the Fifth French Republic (1966) passim online free to borrow

- ^ Helen Parr, "Saving the Community: The French response to Britain's second EEC application in 1967." Cold War History 6#4 (2006): 425–454.

- ^ (in French) À Londres, pompe royale pour le couple Sarkozy Archived 19 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine – Le Point

- ^ Ronald Tiersky; John Van Oudenaren (2010). European Foreign Policies: Does Europe Still Matter?. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 167. ISBN 9780742557802.

- ^ Kettle, Martin (5 April 2004). "The odd couple". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "French-UK links to be strengthened in 'entente formidable'". Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ "News | The Scotsman". Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Sarkozy: We are stronger together – BBC

- ^ President pays tribute to Britain and calls for 'brotherhood' – The Guardian

- ^ Nicolas Sarkozy: 'France will never forget Britain's war sacrifice' – The Daily Telegraph

- ^ "Sarkozy: Britain, France stronger together". United International Press. 26 March 2008. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- ^ "'Brexit' Aftershocks: More Rifts in Europe, and in Britain, Too". The New York Times. 25 June 2016.

- ^ "EU calls for UK to 'Brexit' quickly; Britain wants more time". The Times of India. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "World reaction as UK votes to leave EU". BBC News. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Le peuple a tort, changeons de peuple !" (in French). Blog.nicolasdupontaignan.fr. 27 June 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "Fishing row: Turbulence has hit relations with France, PM says". BBC News. 30 October 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "French fishing fleet descends on Jersey as Royal Navy ships arrive on patrol". Sky News. 6 May 2021.

- ^ "Jersey row: fishing leader says French threats 'close to act of war'". The Guardian. 6 May 2021.

- ^ Hughes, Laura; Manson, Katrina; Mallet, Victor; Parker, George (22 September 2021). "Boris Johnson dismisses French anger over Aukus defence pact". The Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "Fishing row: Europe Minister summons French Ambassador over threats made against the UK and Channel Islands". UK GOV. 30 October 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "France Threatens to Ban UK Fishing Vessels Over License Dispute". Maritime Executive. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ Twitter https://twitter.com/francediplo_en/status/1462834768563822609. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Peston, Robert (26 November 2021). "Migrant crisis: Should Johnson be negotiating with Macron via Twitter?". ITV News. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "Channel deaths: Priti Patel disinvited to meeting with France". The Guardian. 26 November 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ Kar-Gupta, Sudip; Kasolowsky, Raissa (6 March 2022). "France urges Britain to do more to help Ukraine refugees in Calais". Reuters. Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Henley, Jon (26 August 2022). "'Serious problem' if France and UK can't tell if they're friends or enemies, says Macron". theguardian. theguardian. theguardian. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Macron, Sunak seek migration deal in unifying summit in Paris". Le Monde. 10 March 2023.

- ^ "King Charles III to begin state visit to France on Wednesday". Le Monde. 16 September 2023.

- ^ Pannier, Alice (2020). Rivals in Arms: The Rise of UK-France Defence Relations in the Twenty-First Century. McGill-Queen's University Press.

- ^ Pop, Valentina (2 November 2010). "/ Defence / France and UK to sign historic defence pact". EUobserver. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ "Q&A: UK-French defence treaty". BBC News. 2 November 2010.

- ^ Rettman, Andrew (19 September 2013). "UK and France going own way on military co-operation". EUobserver. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ Sedghi, Ami (24 February 2010). "UK export and import in 2011: top products and trading partners". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "France travel advice".

- ^ "Brits, Americans or Germans - who visits France the most?". 12 September 2023.

- ^ "2017 snapshot". 28 April 2015. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Franco-British Council (2001). Crossing the Channel (PDF). Franco-British Council. ISBN 0-9540118-2-1.

- ^ "Entente Cordiale scholarships on the website of the French Embassy in the UK". Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Entente Cordiale scholarships on the website of the British Council France

- ^ "UK help and services in France - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Wilson, Iain (2010), Aberystwyth University (ed.), Are International Exchange and Mobility Programmes Effective Tools of Symmetric Public Diplomacy ? (PDF), p. 52, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016, retrieved 6 January 2013

- ^ Samme Chittum, Last Days of the Concorde: The Crash of Flight 4590 and the End of Supersonic Passenger Travel (Smithsonian Institution, 2018).

- ^ Tombs, Robert; Tombs, Isabelle (2007). That Sweet Enemy: The French and the British from the Sun King to the Present. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-4024-7.

- ^ "How the French impressionists came to fall in love with London". 17 October 2017.

- ^ "French | Origin and meaning of french by Online Etymology Dictionary".

- ^ "vice anglais - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Education and Training" (PDF). 11 January 2024.

- ^ "Education and Training" (PDF). 11 January 2024.

- ^ "EUROPA" (PDF). Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^ Finkenstaedt, Thomas; Dieter Wolff (1973). Ordered profusion; studies in dictionaries and the English lexicon. C. Winter. ISBN 978-3-533-02253-4.

- ^ Borger, Julian; Chrisafis, Angelique (26 March 2008). "Brown, Windsor and soccer for Sarkozy visit". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Barkham, Patrick (5 July 2005). "Chirac's reheated food jokes bring Blair to the boil". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Busiest shipping lane". guinnessworldrecords.com. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ "Ferries to France & Spain – Holiday Packages – Brittany Ferries".

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of English (2nd Revised ed.). OUP Oxford. 11 August 2005. ISBN 978-3-411-02144-4.

- ^ Janet Stobart (20 December 2009). "Rail passengers spend a cold, dark night stranded in Chunnel". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Whiteside p. 17

- ^ "The Channel Tunnel". library.thinkquest.org. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ^ Wilson pp. 14–21

- ^ "Seven Wonders". American Society of Civil Engineers. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ "International Air Passenger Traffic To and From Reporting Airports for 2008 Comparison with the Previous Year" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ "Devizes and District Twinning Association". www.devizes-twinning.org.uk. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "France in the UK". uk.ambafrance.org. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "British Embassy Paris - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Chassaigne, Philippe, and Michael Dockrill, eds. Anglo-French Relations 1898-1998: From Fashoda to Jospin (Springer, 2001).

- Gibson, Robert. The Best of Enemies: Anglo-French Relations Since the Norman Conquest (2nd ed. 2011) major scholarly study excerpt and text search

- Horne, Alistair, Friend or Foe: An Anglo-Saxon History of France (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005).

- Johnson, Douglas, et al. Britain and France: Ten Centuries (1980) table of contents

- Tombs, Robert and Isabelle Tombs. That Sweet Enemy: Britain and France: The History of a Love-Hate Relationship (2008) 1688 to present online

To 1918

[edit]- Acomb, Frances Dorothy. Anglophobia in France, 1763–1789: an essay in the history of constitutionalism and nationalism (Duke UP, 1950).

- Andrew, Christopher, "France and the Making of the Entente Cordiale" Historical Journal 10#1 (1967), pp 89–105.

- Andrews, Stuart. The British periodical press and the French Revolution, 1789–99 (Macmillan, 2000)

- Baer, Werner. "The Promoting and the Financing of the Suez Canal" Business History Review (1956) 30#4 pp. 361–381 online

- Baugh, Daniel A. The Global Seven Years' War, 1754–1763: Britain and France in a Great Power Contest (Longman, 2011)

- Bell, Herbert C.F. Lord Palmerston (2 vol 1936), online

- Black, Jeremy. Natural and Necessary Enemies: Anglo-French Relations in the Eighteenth Century (1986).

- Blockley, John Edward. "Cross Channel Reflections: French Perceptions of Britain from Fashoda to the Boer War" (PhD dissertation Queen Mary University of London, 2015). online

- Brogan, D. W. France under the Republic: The Development of Modern France (1870–1939) (1941), Scholarly history by a British expert; 764pp. online

- Brown, David. "Palmerston and Anglo–French Relations, 1846–1865." Diplomacy and Statecraft 17.4 (2006): 675–692. DOI: 10.1080/09592290600942918

- Carroll, E. Malcolm. French Public Opinion and Foreign Affairs, 1870–1914 (1931) online

- Cameron-Ash, M. Lying for the Admiralty: Captain Cook's Endeavour Voyage, 2018, Rosenberg Publishing, Sydney,ISBN 9780648043966

- Clark, Christopher. The sleepwalkers: how Europe went to war in 1914 (2012)

- Crouzet, François. Britain Ascendant. Comparative Studies in Franco-British Economic History (Cambridge UP, 1990).

- Davis, Richard. Anglo-French relations before the Second World War: appeasement and crisis (Springer, 2001).

- Dickinson, Harry Thomas, ed. Britain and the French Revolution, 1789–1815 (1989).

- Golicz, Roman. "Napoleon III, Lord Palmerston and the Entente Cordiale". History Today 50#12 (December 2000): 10–17

- Gifford, Prosser and William Roger Louis. France and Britain in Africa: Imperial Rivalry and Colonial Rule (1971)

- Gooch, G. P., and Harold Temperley, eds. British Documents on the Origins of the War 1898-1914, Vol. II - The Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Franco-British Entente (1927) primary sources pp 259-407; online

- Harris, John R. Industrial Espionage and Technology Transfer: Britain and France in the 18th Century (Taylor & Francis, 2017).

- Harvey, Robert, The War of Wars: The Great European Conflict 1793–1815 (Robinson, 2007).

- Horn, David Bayne. Great Britain and Europe in the eighteenth century (1967) pp 22–85.

- Jacobs, Wilbur R. Diplomacy and Indian gifts: Anglo-French rivalry along the Ohio and Northwest frontiers, 1748–1763 (1950)

- Jones, Colin. Britain and Revolutionary France: Conflict, Subversion, and Propaganda (1983); 96pp

- Keiger, J.F.V. France and the World since 1870 (2001)

- Keiger, John F. V. (1983). France and the origins of the First World War. Macmillan. ISBN 9780333285510.

- Kennan, George Frost. The fateful alliance: France, Russia, and the coming of the First World War (1984); covers 1890 to 1894.

- Langer, William. European Alliances and Alignments 1870–1890 (1950); advanced diplomatic history online

- Langer, William. The Diplomacy of Imperialism 1890–1902 (1950); advanced diplomatic history online

- McLynn, Frank, 1759: The Year Britain Became Master of the World (Pimlico, 2005).

- MacMillan, Margaret. The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (2014) pp 142–71. online

- Mayne, Richard, Douglas Johnson, and Robert Tombs, eds. Cross Channel Currents 100 Years of the Entente Cordiale (Routledge: 2004)

- Millman, Richard. British Foreign Policy and the Coming of the Franco-Prussian War (1965) online

- Newman, Gerald. "Anti-French Propaganda and British Liberal Nationalism in the Early Nineteenth Century: Suggestions Toward a General Interpretation." Victorian Studies (1975): 385–418. JSTOR 3826554

- Otte, T. G. "From 'War-in-Sight' to Nearly War: Anglo–French Relations in the Age of High Imperialism, 1875–1898." Diplomacy and Statecraft (2006) 17#4 pp: 693–714.

- Parry, Jonathan Philip. "The impact of Napoleon III on British politics, 1851–1880." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 11 (2001): 147–175. online; a study in distrust

- Philpott, William James. Anglo-French Relations and Strategy on the Western Front 1914–18 (1996)

- Prete, Roy A. Strategy and Command: The Anglo-French Coalition on the Western Front, 1915 (McGill-Queen's UP, 2021) online review by Michael S. Neiberg

- Raymond, Dora Neill. British policy and opinion during the Franco-Prussian war (1921) online

- Reboul, Juliette. French Emigration to Great Britain in Response to the French Revolution (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

- Rich, Norman. Great Power Diplomacy: 1814–1914 (1991), comprehensive worldwide survey

- Schmidt, H. D. "The Idea and Slogan of 'Perfidious Albion'" Journal of the History of Ideas (1953) pp: 604–616. JSTOR 2707704; on French distrust of "Albion" (i.e. England)

- Schroeder, Paul W. The Transformation of European Politics 1763–1848 (1994) 920pp; advanced history and analysis of major diplomacy

- Seton-Watson, R.W. Britain in Europe: 1789–1914 (1937) detailed survey or foreign policy with much on France; online

- Schuman, Frederick L. War and diplomacy in the French Republic; an inquiry into political motivations and the control of foreign policy (1931)

- Sharp, Alan, & Stone, Glyn, eds. Anglo-French Relations in the Twentieth Century (2000)

- Simms, Brendan, Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire (Penguin Books, 2008), 18th century wars

- Smith, Michael S. Tariff reform in France, 1860–1900: the politics of economic interest (Cornell UP, 1980).

- Taylor, A.J.P. The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918 (1954) 638pp; advanced history and analysis of major diplomacy

- Ward, A.W. and G.P. Gooch, eds. The Cambridge History Of British Foreign Policy 1783-1919 (3 vol 1922), multiple chaptrs on France. online

Since 1919

[edit]- Adamthwaite, Anthony. Grandeur and Misery: France's Bid for Power in Europe, 1914–1940 (Hodder Arnold, 1995).

- Alexander, Martin S. and William J. Philpott. Anglo-French Defence Relations Between the Wars (2003), 1919–39 excerpt and text search

- Bell, P. M. H. France and Britain, 1900–1940: Entente and Estrangement (2nd ed. 2014).

- Bell, P. M. H. France and Britain, 1940–1994: The Long Separation (1997).

- Berthon, Simon. Allies at War: The Bitter Rivalry among Churchill, Roosevelt, and de Gaulle (2001). 356 pp.

- Boyce, Robert, ed. French foreign and defence policy, 1918–1940: the decline and fall of a great power (Routledge, 2005).

- Brunschwig, Henri. Anglophobia and French African Policy (Yale UP, 1971).

- Capet, Antoine, ed. Britain, France and the Entente Cordiale Since 1904 (Palgrave Macmillan 2006).

- Chassaigne, Philippe, and Michael Lawrence Dockrill, eds. Anglo-French Relations 1898–1998: From Fashoda to Jospin (Palgrave, 2002)

- Clarke, Michael. "French and British security: mirror images in a globalized world." International Affairs 76.4 (2000): 725–740. Online[permanent dead link]

- Crossley, Ceri, and Ian Small, eds. Studies in Anglo French Cultural Relations: Imagining France (1988)

- Davis, Richard. Anglo-French Relations before the Second World War: Appeasement and Crisis (2001)

- Fenby, Jonathan (2012). The General: Charles De Gaulle and the France He Saved. Skyhorse. ISBN 9781620874479.

- Funk, Arthur Layton. Charles de Gaulle: the crucial years, 1943-1944 (1959).

- Grayson, Richard S. Austen Chamberlain and the Commitment to Europe: British Foreign Policy 1924-1929 (Routledge, 2014).

- Johnson, Gaynor. "Sir Austen Chamberlain, the Marquess of Crewe and Anglo-French Relations, 1924–1928." Contemporary British History 25.01 (2011): 49–64. online

- Hucker, Daniel. Public opinion and the end of appeasement in Britain and France (Routledge, 2016).

- Jennings, Eric T. "Britain and Free France in Africa, 1940–1943." in British and French Colonialism in Africa, Asia and the Middle East (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2019) pp. 277–296.

- Keiger, J.F.V. France and the World since 1870 (2001)

- Kolodziej, Edward A. French International Policy under de Gaulle and Pompidou: The Politics of Grandeur (1974)

- Lahav, Pnina. "The Suez Crisis of 1956 and Its Aftermath: A Comparative Study of Constituons, Use of Force, Diplomacy and International Relations." Boston University Law Review 95 (2015): 1297–1354 online

- MacMillan, Margaret, Peacemakers: Six Months that Changed the World (2003) on Versailles Conference of 1919 online

- Maclean, Mairi, and Jean-Marie Trouille, eds. France, Germany and Britain: Partners in a Changing World (Palgrave Macmillan, 2001).

- Mayne, Richard et al. Cross-Channel Currents: 100 Years of the Entente Cordiale (2004)

- Nere, J. The Foreign Policy of France from 1914 to 1945 (2002)

- Oye, Kenneth A. "The sterling-dollar-franc triangle: Monetary diplomacy 1929–1937." World Politics (1985) 38#1 pp: 173–199.

- Pickles, Dorothy. The Uneasy Entente. French Foreign Policy and Franco-British Misunderstandings (1966).

- Roshwald, Aviel. Estranged Bedfellows: Britain and France in the Middle East During the Second World War (Oxford UP, 1990).

- Scazzieri, Luigi. "Britain, france, and Mesopotamian oil, 1916–1920." Diplomacy & Statecraft 26.1 (2015): 25–45.

- Sharp, Alan et al. eds. Anglo-French Relations in the Twentieth Century: Rivalry and Cooperation (2000) excerpt and text search

- Thomas, Martin. Britain, France and Appeasement: Anglo-French Relations in the Popular Front Era (1996) * Thomas, R. T. Britain and Vichy: The Dilemma of Anglo-French Relations, 1940–42 (1979)

- Torrent, Melanie. Diplomacy and Nation-Building in Africa: Franco-British Relations and Cameroon at the End of Empire (I.B. Tauris, 2012) 409 pages

- Troen, S. Ilan. "The Protocol of Sèvres: British/French/Israeli Collusion Against Egypt, 1956." Israel Studies 1.2 (1996): 122-139 online.

- Varble, Derek (2003). The Suez Crisis 1956. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1841764184. on 1956.

- Webster, Andrew. Strange Allies: Britain, France and the Dilemmas of Disarmament and Security, 1929-1933 (Routledge, 2019).

- Williams, Andrew. France, Britain and the United States in the Twentieth Century 1900–1940: A Reappraisal (Springer, 2014).

- Zamir, Meir. "De Gaulle and the question of Syria and Lebanon during the Second World War: Part I." Middle Eastern Studies 43.5 (2007): 675–708.

In French

[edit]- Guiffan, Jean. Histoire de l'anglophobie en France: de Jeanne d'Arc à la vache folle (Terre de brume, 2004)

- Nordmann, Claude. "Anglomanie et Anglophobie en France au XVIIIe siècle'." Revue du Nord 66 (1984) pp: 787–803.

- Serodes, Fabrice. "French – English: 100 Years of “Friendly Disagreement?", Europeplusnet (2004)

- Serodes, Fabrice. "'Historical use of a caricature. The destiny of the perfidious Albion.", Brussels, VUB, 2009.

- Serodes, Fabrice Anglophobie et politique de Fachoda à Mers el-Kebir (L Harmattan, 2010)

- Serodes, Fabrice "Brexit: le Royaume-Uni sort, ses idées restent", The Conversation, 17 January 2017

External links

[edit] Media related to Relations of France and the United Kingdom at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Relations of France and the United Kingdom at Wikimedia Commons- Franco-British Council Links

- University of London in Paris (ULIP)

- French Embassy in the United Kingdom Archived 7 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- British Embassy in France Archived 16 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

KSF

KSF