Fujian flu

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 21 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 21 min

- See Influenza for details about the illnesses and Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 and Influenza A virus subtype H3N2 for details about the causative agents.

| Fujian flu | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Insthoviricetes |

| Order: | Articulavirales |

| Family: | Orthomyxoviridae |

| Genus: | Alphainfluenzavirus |

| Species: | Influenza A virus |

| Groups included | |

| |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

|

All other subtypes and strains of Influenza A virus | |

| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

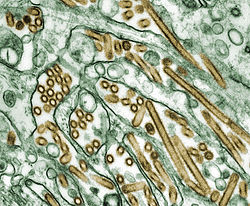

Fujian flu refers to flu caused by either a Fujian human flu strain of the H3N2 subtype of the Influenza A virus or a Fujian bird flu strain of the H5N1 subtype of the Influenza A virus. These strains are named after Fujian, a coastal province in Southeast China.[note 1]

A/Fujian (H3N2) human flu (from A/Fujian/411/2002(H3N2) -like flu virus strains) caused an unusually severe 2003–2004 flu season. This was due to a reassortment event that caused a minor clade to provide a haemagglutinin gene that later became part of the dominant strain in the 2002–2003 flu season. A/Fujian (H3N2) was made part of the trivalent influenza vaccine for the 2004-2005 flu season and its descendants are still the most common human H3N2 strain.

A/Fujian (H5N1) bird flu is notable for its resistance to standard medical countermeasures and its rapid spread. This variant of the H5N1 virus also illustrates the continuing evolution of the H5N1 virus, and its emergence has caused political controversy.

Terminology

[edit]A variety of names were used before being standardized.[1] Phrases used to identify the flu or the causative agent include "Fujian-like"[2][3] and "Fujian virus"[4] for the H5N1 version and "Fujian-like"[5] for the H3N2 version.

Both are also sometimes specified as "Type A Fujian flu" or "A/Fujian flu" referring to the species Influenza A virus. Both are also sometimes specified according to their species subtype: "Fujian Flu (H3N2)" or "Fujian Flu (H5N1)". Or both, example: "A-Fujian-H3N2".

"A/Fujian/411/2002-like (H3N2)" and "Influenza A/Fujian/411/02(H3N2)-lineage viruses" are examples of using the full name of the virus strains.[citation needed]

A/Fujian (H3N2)

[edit]In the 2003-2004 flu season the influenza vaccine was produced to protect against A/Panama (H3N2), A/New Caledonia (H1N1), and B/Hong Kong. A new strain, A/Fujian (H3N2), was discovered after production of the vaccine started and vaccination gave only partial protection against this strain. Nature magazine reported that the Influenza Genome Sequencing Project, using phylogenetic analysis of 156 H3N2 genomes, "explains the appearance, during the 2003–2004 season, of the 'Fujian/411/2002'-like strain, for which the existing vaccine had limited effectiveness" as due to an epidemiologically significant reassortment. "Through a reassortment event, a minor clade provided the haemagglutinin gene that later became part of the dominant strain after the 2002–2003 season. Two of our samples, A/New York/269/2003 (H3N2) and A/New York/32/2003 (H3N2), show that this minor clade continued to circulate in the 2003–2004 season, when most other isolates were reassortants."[6]

In January 2004, the predominant flu virus circulating in humans in Europe was influenza A/Fujian/411/2002 (H3N2)-like.[7]

As of 15 June 2004, CDC had antigenically characterized 1,024 influenza viruses collected by U.S. laboratories since 1 October 2003: 949 influenza A (H3N2) viruses, three influenza A (H1) viruses, one influenza A (H7N2) virus, and 71 influenza B viruses. Of the 949 influenza A (H3N2) isolates characterized, 106 (11.2%) were similar antigenically to the vaccine strain A/Panama/2007/1999 (H3N2), and 843 (88.8%) were similar to the drift variant, A/Fujian/411/2002 (H3N2).[8]

The 2004-2005 flu season trivalent influenza vaccine for the United States contained A/New Caledonia/20/1999-like (H1N1), A/Fujian/411/2002-like (H3N2), and B/Shanghai/361/2002-like viruses.[8]

Flu Watch reported for 13 to 19 February 2005 that:

- "The National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) has antigenically characterized 516 influenza viruses: 470 influenza A (H3N2) and 46 influenza B viruses. Of the 470 influenza A (H3N2), 427 (91%) were A/Fujian/411/2002 (H3N2)-like and 43 (9%) A/California/7/2004-like viruses. Of the 46 influenza B, 45 were B/Shanghai/361/02-like and one B/HongKong/330/2001-like virus. Although the A/California/7/2004 (H3N2)-like isolates have reduced titres to the A/Fujian/411/2002-like antisera, the H3N2 component of the current vaccine is still expected to provide some level of protection against this new variant. The WHO has recommended that the vaccine for the 2005/06 northern hemisphere season contain the A/California/7/2004 (H3N2)-like virus."[9]

A/Fujian (H5N1)

[edit] |

Specific H5N1 isolates labeled as Fujian include A/Fujian/1/2005 and A/DK/Fujian/1734/05 (or A/Ck/Fujian/1734/2005).[10]

A/Fujian (H5N1) bird flu is notable for its resistance to standard medical countermeasures, its rapid spread, what it tells us about the continuing evolution of the H5N1 virus, and the political controversy surrounding it. CIDRAP says "A new subtype of H5N1 avian influenza virus has become predominant in southern China over the past year, possibly through its resistance to vaccines used in poultry, and has been found in human H5N1 cases in China, according to researchers from Hong Kong and the United States. The rise of the Fujian-like strain seems to be the cause of increased poultry outbreaks and recent human cases in China, according to the team from the University of Hong Kong and St. Jude's Children's Research Hospital in Memphis. The researchers also found an overall increase of H5N1 infection in live-poultry markets in southern China."[11][12][13][14][15][16]

Resistance to countermeasures

[edit]According to the New York Times: "[P]oultry vaccines, made on the cheap, are not filtered and purified [like human vaccines] to remove bits of bacteria or other viruses. They usually contain whole virus, not just the hemagglutinin spike that attaches to cells. Purification is far more expensive than the work in eggs, Dr. Stöhr said; a modest factory for human vaccine costs $100 million, and no veterinary manufacturer is ready to build one. Also, poultry vaccines are "adjuvated" – boosted – with mineral oil, which induces a strong immune reaction but can cause inflammation and abscesses. Chicken vaccinators who have accidentally jabbed themselves have developed painful swollen fingers or even lost thumbs, doctors said. Effectiveness may also be limited. Chicken vaccines are often only vaguely similar to circulating flu strains – some contain an H5N2 strain isolated in Mexico years ago. 'With a chicken, if you use a vaccine that's only 85 percent related, you'll get protection,' Dr. Cardona said. 'In humans, you can get a single point mutation, and a vaccine that's 99.99 percent related won't protect you.' And they are weaker [than human vaccines]. 'Chickens are smaller and you only need to protect them for six weeks, because that's how long they live till you eat them,' said Dr. John J. Treanor, a vaccine expert at the University of Rochester. Human seasonal flu vaccines contain about 45 micrograms of antigen, while an experimental A(H5N1) vaccine contains 180. Chicken vaccines may contain less than 1 microgram. 'You have to be careful about extrapolating data from poultry to humans,' warned Dr. David E. Swayne, director of the agriculture department's Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory. 'Birds are more closely related to dinosaurs.'"[17][excessive quote] Researchers, led by Nicholas Savill of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, used mathematical models to simulate the spread of H5N1 and concluded that "at least 95 per cent of birds need to be protected to prevent the virus spreading silently. In practice, it is difficult to protect more than 90 per cent of a flock; protection levels achieved by a vaccine are usually much lower than this."[18]

Referring to the Fujian-like strain, an October 2006 National Academy of Sciences article reports: "The development of highly pathogenic avian H5N1 influenza viruses in poultry in Eurasia accompanied with the increase in human infection in 2006 suggests that the virus has not been effectively contained and that the pandemic threat persists. [...] Serological studies suggest that H5N1 seroconversion in market poultry is low and that vaccination may have facilitated the selection of the Fujian-like sublineage. The predominance of this virus over a large geographical region within a short period directly challenges current disease control measures."[11] The research team tested more than 53,000 birds in southern China from July 2005 through June 2006. 2.4% of the birds had H5N1, more than double the previous 0.9% rate. 68% them were in the new Fujian-like lineage. First detected in March 2005, it constituted 103 of 108 bird hosted isolates tested from April through June 2006, five Chinese human hosted isolates, 16 from Hong Kong birds, and two from Laos and Malaysia birds. Chickens in southern China were found to be poorly immunized against Fujian-like viruses in comparison with other sublineages. "All the analyzed Fujian-like viruses had molecular characteristics that indicated sensitivity to oseltamivir, the first-choice antiviral drug for H5N1 infection. In addition, only six of the viruses had a mutation that confers resistance to amantadine, an older antiviral drug used to treat flu."[12]

Rapid spread

[edit]"China's official Xinhua news agency says a new bird flu outbreak has killed more than 3,000 chickens in the northwest. The Ministry of Agriculture told Xinhua that the July 14 outbreak in Xinjiang region's Aksu city is under control. No human infections have been reported. Saturday's report says the deadly H5N1 virus killed 3,045 chickens, and nearly 357,000 more were destroyed in an emergency response. Xinhua says the local agriculture department has quarantined the infected area. The government's last reported outbreak was in the northwestern region of Ningxia earlier this month."[19]

The October 2006 National Academy of Sciences article also says: "Updated virological and epidemiological findings from our market surveillance in southern China demonstrate that H5N1 influenza viruses continued to be panzootic in different types of poultry. Genetic and antigenic analyses revealed the emergence and predominance of a previously uncharacterized H5N1 virus sublineage (Fujian-like) in poultry since late 2005. Viruses from this sublineage gradually replaced those multiple regional distinct sublineages and caused recent human infection in China. These viruses have already transmitted to Hong Kong, Laos, Malaysia, and Thailand, resulting in a new transmission and outbreak wave in Southeast Asia."[11]

H5N1 evolution

[edit]The first known strain of HPAI A(H5N1) (called A/chicken/Scotland/59) killed two flocks of chickens in Scotland in 1959; but that strain was very different from the current highly pathogenic strain of H5N1. The dominant strain of HPAI A(H5N1) in 2004 evolved from 1999 to 2002 creating the Z genotype.[20] It has also been called "Asian lineage HPAI A(H5N1)".

H5N1 is an Influenza A virus subtype. Experts believe it might mutate into a form that transmits easily from person to person. If such a mutation occurs, it might remain an H5N1 subtype or could shift subtypes as did H2N2 when it evolved into the Hong Kong Flu strain of H3N2.[citation needed]

H5N1 has mutated[21] through antigenic drift into dozens of highly pathogenic varieties, but all currently belonging to genotype Z of avian influenza virus H5N1. Genotype Z emerged through reassortment in 2002 from earlier highly pathogenic genotypes of H5N1 that first appeared in China in 1996 in birds and in Hong Kong in 1997 in humans.[22] The "H5N1 viruses from human infections and the closely related avian viruses isolated in 2004 and 2005 belong to a single genotype, often referred to as genotype Z."[21]

In July 2004, researchers led by H. Deng of the Harbin Veterinary Research Institute, Harbin, China and Professor Robert G. Webster of the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee, reported results of experiments in which mice had been exposed to 21 isolates of confirmed H5N1 strains obtained from ducks in China between 1999 and 2002. They found "a clear temporal pattern of progressively increasing pathogenicity".[23] Results reported by Dr. Webster in July 2005 reveal further progression toward pathogenicity in mice and longer virus shedding by ducks.

Asian lineage HPAI A(H5N1) is divided into two antigenic clades. "Clade 1 includes human and bird isolates from Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia and bird isolates from Laos and Malaysia. Clade 2 viruses were first identified in bird isolates from China, Indonesia, Japan, and South Korea before spreading westward to the Middle East, Europe, and Africa. The clade 2 viruses have been primarily responsible for human H5N1 infections that have occurred during late 2005 and 2006, according to WHO. Genetic analysis has identified six subclades of clade 2, three of which have a distinct geographic distribution and have been implicated in human infections:

On 18 August 2006, the World Health Organization (WHO) changed the H5N1 avian influenza strains recommended for candidate vaccines for the first time since 2004. "Many experts who follow the ongoing analysis of the H5N1 virus sequences are alarmed at how fast the virus is evolving into an increasingly more complex network of clades and subclades, Osterholm said. The evolving nature of the virus complicates vaccine planning. He said if an avian influenza pandemic emerges, a strain-specific vaccine will need to be developed to treat the disease. Recognition of the three new subclades means researchers face increasingly complex options about which path to take to stay ahead of the virus."[24][25]

Political controversy

[edit]"Human disease associated with influenza A subtype H5N1 re-emerged in January 2003, for the first time since an outbreak in Hong Kong in 1997." Three people in one family were infected after visiting Fujian province in mainland China and 2 died.[26] By midyear of 2003 outbreaks of poultry disease caused by H5N1 occurred in Asia, but were not recognized as such. That December animals in a Thai zoo died after eating infected chicken carcasses. Later that month H5N1 infection was detected in 3 flocks in the Republic of Korea.[27] H5N1 in China in this and later periods is less than fully reported. Blogs have described many discrepancies between official China government announcements concerning H5N1 and what people in China see with their own eyes. Many reports of total H5N1 cases exclude China due to widespread disbelief in China's official numbers.[28][29][30][31]

According to the CDC article H5N1 Outbreaks and Enzootic Influenza by Robert G. Webster et al.:"Transmission of highly pathogenic H5N1 from domestic poultry back to migratory waterfowl in western China has increased the geographic spread. The spread of H5N1 and its likely reintroduction to domestic poultry increase the need for good agricultural vaccines. In fact, the root cause of the continuing H5N1 pandemic threat may be the way the pathogenicity of H5N1 viruses is masked by cocirculating influenza viruses or bad agricultural vaccines."[32] Dr. Robert Webster explains: "If you use a good vaccine you can prevent the transmission within poultry and to humans. But if they have been using vaccines now [in China] for several years, why is there so much bird flu? There is bad vaccine that stops the disease in the bird but the bird goes on pooping out virus and maintaining it and changing it. And I think this is what is going on in China. It has to be. Either there is not enough vaccine being used or there is substandard vaccine being used. Probably both. It's not just China. We can't blame China for substandard vaccines. I think there are substandard vaccines for influenza in poultry all over the world."[33] In response to the same concerns, Reuters reports Hong Kong infectious disease expert Lo Wing-lok saying, "The issue of vaccines has to take top priority," and Julie Hall, in charge of the WHO's outbreak response in China, saying "China's vaccinations might be masking the virus."[34] The BBC reported that Dr Wendy Barclay, a virologist at the University of Reading, UK said: "The Chinese have made a vaccine based on reverse genetics made with H5N1 antigens, and they have been using it. There has been a lot of criticism of what they have done, because they have protected their chickens against death from this virus but the chickens still get infected; and then you get drift - the virus mutates in response to the antibodies - and now we have a situation where we have five or six 'flavours' of H5N1 out there."[35]

In October 2006, China and WHO traded accusations over the Fujian-like strain. Chinese authorities rejected the Fujian-like strain interpretation altogether saying "Gene sequence analysis shows that all the variants of the virus found in southern China share high uniformity, meaning they all belong to the same gene type. No distinctive change was found in their biological characteristics." While a World Health Organization official in China renewed previous complaints that the Chinese have been stingy with information about H5N1 in poultry saying "There's a stark contrast between what we're hearing from the researchers and what the Ministry of Agriculture says. Unless the ministry tells us what's going on and shares viruses on a regular basis, we will be doing diagnostics on strains that are old."[12]

In November 2006, China and WHO traded favors over their H5N1 disagreements with a face-saving WHO apology and China promising to share more avian influenza virus samples.[13] Also in November, Margaret Chan, a former top government health official for Hong Kong, was made Director-General elect of the WHO. The Chinese government said they "would fully support her work in the WHO so that she could wholeheartedly carry out her responsibility and serve the health cause of the world."[36]

In December 2006, Chinese authorities agreed that Fujian flu exists; but said that "Anhui" should replace the word "Fujian" in its name.[37] Other names it has been called include "waterfowl clade" and "clade 2.3".[38] (Or more specifically, "Clade 2.3.4"[39])

China provided 20 H5N1 samples from birds in late 2006 gleaned from birds a year earlier and in 2006 shared a significant amount of H5N1 information generated by its labs. On 31 May 2007, for the first time in almost a year, China shared H5N1 avian flu virus samples taken from humans with WHO. The samples were taken from two people and arrived at a World Health Organization (WHO) laboratory in the United States that is part of CDC. A WHO official said that these are two of the three samples promised to WHO and have been sent by China's health ministry. The specimens are from a 2006 case from Xinjiang province in far western China and a 2007 case from Fujian province in the south. The third promised but not yet delivered sample is from a 24-year-old soldier who died in 2003. China previously sent six human H5N1 virus samples to WHO laboratories: two in December 2005 and four in May 2006.[40]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Agencies to seek accord on naming of H5N1 strains". Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. 11 December 2006. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Li, Yanbing; Shi, Jianzhong; Zhong, Gongxun; Deng, Guohua; Tian, Guobin; Ge, Jinying; Zeng, Xianying; Song, Jiasheng; Zhao, Dongming; Liu, Liling; Jiang, Yongping (September 2010). "Continued Evolution of H5N1 Influenza Viruses in Wild Birds, Domestic Poultry, and Humans in China from 2004 to 2009". Journal of Virology. 84 (17): 8389–8397. doi:10.1128/JVI.00413-10. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 2919039. PMID 20538856.

- ^ "Avian Flu - The Chronology of a Disease". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Medical News Today article H5N1 Bird Flu Virus Is Changing, FAO And OIE Recommend Increased Surveillance When Vaccinating published 10 November 2006

- ^ "Hot topic - Fujian-like strain A influenza". Archived from the original on 10 December 2006. Retrieved 11 November 2006.

- ^ Ghedin, Elodie; Sengamalay, Naomi A.; Shumway, Martin; Zaborsky, Jennifer; Feldblyum, Tamara; Subbu, Vik; Spiro, David J.; Sitz, Jeff; Koo, Hean; Bolotov, Pavel; Dernovoy, Dmitry; Tatusova, Tatiana; Bao, Yiming; St George, Kirsten; Taylor, Jill; Lipman, David J.; Fraser, Claire M.; Taubenberger, Jeffery K.; Salzberg, Steven L. (2005). "Large-scale sequencing of human influenza reveals the dynamic nature of viral genome evolution". Nature. 437 (7062): 1162–1166. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1162G. doi:10.1038/nature04239. PMID 16208317.

- ^ EISS - Weekly Electronic Bulletin article Influenza activity on the rise in the east of Europe dated 23 January 2004

- ^ a b CDC article Update: Influenza Activity --- United States and Worldwide, 2003–04 Season, and Composition of the 2004–05 Influenza Vaccine published 2 July 2004

- ^ Flu Watch Archived 13 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine 13 to 19 February 2005

- ^ washington.edu Archived 16 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine Ministry of Health, P.R.China 2006-1-20

- ^ a b c Smith, G. J. D.; Fan, X. H.; Wang, J.; Li, K. S.; Qin, K.; Zhang, J. X.; Vijaykrishna, D.; Cheung, C. L.; Huang, K.; Rayner, J. M.; Peiris, J. S. M.; Chen, H.; Webster, R. G.; Guan, Y. (2006). "Emergence and predominance of an H5N1 influenza variant in China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (45): 16936–16941. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10316936S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608157103. PMC 1636557. PMID 17075062.

- ^ a b c CIDRAP article Study says new H5N1 strain pervades southern China published 3 November 2006

- ^ a b CIDRAP article Chinese promise H5N1 samples, deny claim of new strain published 10 November 2006

- ^ Reuters article China scientists call bird flu paper "unscientific" published 7 November 2006

- ^ "hkam.org.hk PDF" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2006. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- ^ WHO PDF Archived 24 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mcneil, Donald G. Jr. (2 May 2006). "Turning to Chickens in Fight with Bird Flu". The New York Times.

- ^ SciDev.Net Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine article Bird flu warning over partial protection of flocks published 16 August 2006

- ^ "China Reports New Bird Flu Outbreak". Voice of America. 22 July 2006. Archived from the original on 14 September 2006.

- ^ Harder, T. C.; Werner, O. (2006). "Avian Influenza". In Kamps, B. S.; Hoffman, C.; Preiser, W. (eds.). Influenza Report 2006. Paris, France: Flying Publisher. ISBN 978-3-924774-51-6. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

This e-book is under constant revision and is an excellent guide to Avian Influenza - ^ a b The World Health Organization Global Influenza Program Surveillance Network (2005). "Evolution of H5N1 viruses in Asia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (10): 1515–1526. doi:10.3201/eid1110.050644. PMC 3366754. PMID 16318689. Figure 1 of the article gives a diagramatic representation of the genetic relatedness of Asian H5N1 hemagglutinin genes from various isolates of the virus.

- ^ WHO (28 October 2005). "H5N1 avian influenza: timeline" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011.

- ^ Chen, H.; Deng, G.; Li, Z.; Tian, G.; Li, Y.; Jiao, P.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Webster, R. G.; Yu, K. (2004). "The evolution of H5N1 influenza viruses in ducks in southern China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (28): 10452–7. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10110452C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403212101. PMC 478602. PMID 15235128.

- ^ a b "WHO changes H5N1 strains for pandemic vaccines, raising concern over virus evolution". CIDRAP. 18 August 2006.

- ^ a b "Antigenic and genetic characteristics of H5N1 viruses and candidate H5N1 vaccine viruses developed for potential use as pre-pandemic vaccines" (PDF). WHO. 18 August 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2006.

- ^ Peiris JS, Yu WC, Leung CW, Cheung CY, Ng WF, Nicholls JM, Ng TK, Chan KH, Lai ST, Lim WL, Yuen KY, Guan Y (21 February 2004). "Re-emergence of fatal human influenza A subtype H5N1 disease". Lancet. 363 (9409): 617–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15595-5. PMC 7112424. PMID 14987888.

- ^ WHO. "Confirmed Human Cases of Avian Influenza A(H5N1)". Archived from the original on 18 February 2004.

- ^ WHO (19 January 2006). "Confirmed Human Cases of Avian Influenza A(H5N1)". Archived from the original on 13 February 2006.

- ^ Helen Branswell (21 June 2006). "China had bird flu case two years earlier than Beijing admits: researchers". CBC News.

- ^ WHO (27 February 2003). "Influenza A(H5N1) in Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China". Disease Outbreak News: Avian Influenza A(H5N1). 2. Archived from the original on 22 August 2003.

- ^ WHO. "Chronology of a serial killer". Disease Outbreak News: SARS. 95. Archived from the original on 9 July 2003.

- ^ CDC H5N1 Outbreaks and Enzootic Influenza by Robert G. Webster et al.

- ^ MSNBC quoting Reuters quoting Robert G. Webster

- ^ Reuters

- ^ "Bird flu vaccine no 'silver bullet'". 22 February 2006.

- ^ news.xinhuanet article Chinese minister refutes reports on new H5N1 strain published 10 November 2006

- ^ Canada News Archived 12 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine article UN agencies, China agree bird flu variant not new; urge greater surveillance published 8 December 2006

- ^ CIDRAP article Agencies to seek accord on naming of H5N1 strains published 11 December 2006

- ^ Abkhazia Institute for Social and Economic Research[usurped] article Towards a unified nomenclature system for the highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses by Ramaz Mitaishvili published 14 August 2007

- ^ Scientific American article China shares bird flu sample, first time in year: WHO published 1 June 2007 CIDRAP article China resumes sending human H5N1 samples published 25 May 2007 CIDRAP article China said to be withholding H5N1 virus samples published 16 April 2007

Further reading

[edit]- Journal of Virology, June 2005, p. 6763-6771, Vol. 79, No. 11 article Improvement of Influenza A/Fujian/411/02 (H3N2) Virus Growth in Embryonated Chicken Eggs by Balancing the Hemagglutinin and Neuraminidase Activities, Using Reverse Genetics

External links

[edit]- Influenza Research Database – Database of influenza genomic sequences and related information.

KSF

KSF