Galicians

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 53 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 53 min

Galician bagpipers | |

| Total population | |

c. 3.2 million[1]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| | |

| | 2,397,613[2][3] |

| Province of A Coruña | 991,588[2][3] |

| Province of Pontevedra | 833,205[2][3] |

| Province of Lugo | 300,419[2][3] |

| Province of Ourense | 272,401[2][3] |

| 355,063[2][3] | |

| 147,062[4] | |

| 38,440–46,882[4][5] | |

| 38,554[4] | |

| 35,369[4] | |

| 31,077[4] | |

| 30,737[4] | |

| 16,075[4] | |

| 14,172[4] | |

| 13,305[4] | |

| 10,755[4] | |

| 9,895[4] | |

| Galicians inscribed in the electoral census and living abroad combined (2013) | 414,650[4] |

| Languages | |

| Galician, Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism[6] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Portuguese, Asturians, Leonese people, other Spaniards | |

Galicians (Galician: galegos [ɡaˈleɣʊs] or pobo galego; Spanish: gallegos [ɡaˈʎeɣos]) are an ethnic group[7][8] primarily residing in Galicia, northwest Iberian Peninsula. Historical emigration resulted in populations in other parts of Spain, Europe, and the Americas. Galicians possess distinct customs, culture, language, music, dance, sports, art, cuisine, and mythology. Galician, a Romance language derived from the Latin of ancient Roman Gallaecia, is their native language and a primary cultural expression. It shares a common origin with Portuguese, exhibiting 85% intelligibility, and similarities with other Iberian Romance languages like Asturian and Spanish. They are closely related to the Portuguese people.[9][10] Two Romance languages are widely spoken and official in Galicia: the native Galician and Spanish.[11]

Etymology

[edit]

The ethnonym of the Galicians (galegos) derives directly from the Latin Gallaeci or Callaeci, itself an adaptation of the name of a local Celtic tribe[12][13][14] known to the Greeks as Καλλαϊκoί (Kallaikoí). They lived in what is now Galicia and northern Portugal and were defeated by the Roman General Decimus Junius Brutus Callaicus in the 2nd century BCE and later conquered by Augustus.[15] The Romans later applied that name to all the people who shared the same culture and language in the north-west, from the Douro River valley in the south to the Cantabrian Sea in the north and west to the Navia River. That encompassed such tribes as the Celtici, the Artabri, the Lemavi and the Albiones.

The oldest known inscription referring to the Gallaeci (reading Ἔθνο[υς] Καλλαικῶ[ν], "people of the Gallaeci") was found in 1981 in the Sebasteion of Aphrodisias, Turkey; a triumphal monument to Roman Emperor Augustus mentions them among other 15 nations that he conquered.[16]

The etymology of the name has been studied since the 7th century by authors such as Isidore of Seville, who wrote, "Galicians are called so because of their fair skin, as the Gauls" and related the name to the Greek word for "milk," γάλα (gála). However, modern scholars like J.J. Moralejo[15] and Carlos Búa[17] have derived the name of the ancient Callaeci either from Proto-Indo-European *kl̥(H)‑n‑ 'hill', through a local relational suffix -aik-, also attested in Celtiberian language and so meaning 'the highlanders'; or either from Proto-Celtic *kallī- 'forest' and so means 'the forest (people)'.[18]

Another recent proposal comes from the linguist Francesco Benozzo, who is not specialized in Celtic languages and identified the root gall- / kall- in a number of Celtic words with the meaning "stone" or "rock", as follows: gall (old Irish), gal (Middle Welsh), gailleichan (Scottish Gaelic), galagh (Manx) and gall (Gaulish). Hence, Benozzo explains the name Callaecia and its ethnonym Callaeci as being "the stone people" or "the people of the stone" ("those who work with stones"), in reference to the ancient megaliths and stone formations that are so common in Galicia and Portugal.[19] Specialists of the Celtic languages do not consider there is a hypothetical Gaulish root *gall meaning "stone" or "rock", but *galiā "strength" (> French gaill-ard "strong"), related to Old Irish gal "berserk rage, war fury", Welsh gallu and Breton galloud "power".[20] It is distinct from Gaulish *cal(l)io- "hoof" or "testicle",[21][22] related to Welsh caill, Breton kell "testicle" (> Gaulish *caliavo > Old French chaillou, French caillou),[21][23] all from the Proto-Indo-European root *kal- "hard hardness" (perhaps via suffixed zero-grade *kl̥H-no-(m)). For instance, in Latin callum "hard or thick substance" is also found and so both E. Rivas and Juan J. Moralejo relate the toponym Gallaecia / Callaecia with the Latin word callus.[24]

Languages

[edit]Galician

[edit]

Galician is a Romance language belonging to the Western Ibero-Romance branch, deriving from Latin, and holds official status in Galicia. It is also spoken in bordering areas of Asturias and Castile and León.[25]

Medieval or Old Galician, known linguistically as Galician-Portuguese, evolved in the Northwest Iberian Peninsula from Vulgar Latin, becoming the written and spoken language of the medieval Galicia and Portugal. This language developed a notable literary tradition from the late 12th century and gradually replaced Latin in public and private documents in Galicia, Portugal, and neighboring regions.[26]

From the 15th century, Galician-Portuguese diverged into Galician and Portuguese. Galician evolved primarily as a regional spoken language influenced by Castilian Spanish, while Portuguese became an international language. Despite this divergence, the two languages remain closely related, particularly northern Portuguese dialects and Galician.[26] The Royal Galician Academy, the official regulatory institution for the Galician language, considers modern Galician an independent Ibero-Romance language closely related to Portuguese, particularly its northern dialects.

While Galician has official recognition, its socio-linguistic development faces the increasing influence of Spanish and a persistent linguistic erosion due to media and the legal imposition of Spanish in education.[citation needed]

Galicia also maintains a significant literary and oral tradition of songs, tales, and sayings, contributing to the spread and development of the Galician language, sharing commonalities with that of Portugal.[citation needed]

Surnames

[edit]Galician surnames,[27][28] as is the case in most European cultures, can be divided into patronymic (originally based on one's father's name), occupational, toponymic or cognominal. The first group, patronymic includes many of the most frequent surnames and became fixed during the Low Middle Ages; it includes surnames derived from etyma formed with or without the additions of the patronymical suffixes -az, -ez, -iz: Alberte (Albert); Afonso (Alfons); Anes, Oanes, Yanes (Iohannes); Arias; Bernárdez (Bernard); Bermúdez (Medieval Galician Uermues, cf. Wermuth); Cristobo (Christopher); Diz (from Didaci); Estévez (Stephan); Fernández; Fiz (from Felici); Froiz, Frois (From Froilaci, from the Gothic personal name Froila, "lord"); Giance (Latin Iulianici); González; Henríquez (Henry); Martís (Martin); Méndez (Menendici); Miguéns, Miguez (from Michaelici, equivalent to Michaels); Páez, Pais, Paz (from Pelagici, Pelagio); Ramírez; Reimúndez (Raymond); Rodríguez; Sánchez; Sueiro (from Suarius); Tomé (from Thomas); Viéitez, Vieites (Benedictici, Benedict), among many others.

Because of the settlement of Galician colonists in southern Spain during the Reconquista, some of the more frequent and distinctively Galician surnames also became popular in Spanish (which had its own related forms) and were taken later into the Americas, as a consequence of the expansion of the Spanish empire:

| English name | Old Galician (13-15th c.) | Modern Galician | Spanish |

|---|---|---|---|

| John | Eanes | Anes, Oanes, Yanes | Yáñez, Ibáñez |

| Stephen | Esteuaes, Esteuaez, Esteueez | Estévez | Estévanez |

| - | Froes, Froez | Fróiz, Frois | Flores, Flórez |

| Julian | Giançe, Gianz, Gians | Giance | Juliánez |

| Ermengild | Meendez, Meendes | Méndez | Menéndez, Meléndez |

| Martin | Martiiz | Martíns, Martís | Martínez |

| Michael | Migueez | Miguéns, Míguez | Miguélez |

| Pelagius | Paaez, Paaz | Páes, Paiz, Paz | Peláez |

| - | Veasques, Vaasquez | Vázquez | Velázquez, Blázquez |

| Benedict | Beeytez, Beeytes | Viéitez, Vieites | Benítez |

The largest surname group is the one derived from toponyms, which usually referred to the place of origin or residence of the bearer. These places can be European countries (as is the case in the surnames Bretaña, Franza, España, Portugal) or nations (Franco, "Frenchman"); Galician regions (Bergantiños, Carnota, Cavarcos, Sanlés); or cities, towns or villages, which gave origin to a few thousand surnames. Another related group is formed with the preposition de, usually contracted with the definite article as da or do, and a common appellative: Dacosta (or Da Costa), "of the slope", Dopazo or Do Pazo ("of the palace/manor house"); Doval, "of the valley" (cfr. French Duval), Daponte ("of the bridge"), Davila ("of the town", not to be confused with Spanish Dávila), Daporta ("of the gate"); Dasilva ("of the forest"), Dorrío ("of the river"), Datorre ("of the Tower"). Through rebracketing, some of these surnames gave origin to others such as Acosta or Acuña.

A few of these toponymic surnames can be considered nobiliary, as they first appear as the name of some Galician noble houses,[29] later expanding when these nobles began to serve as officials of the Spanish Empire, in Spain or elsewhere, as a way of maintaining them both far from Galicia and useful to the Empire: Andrade (from the house of Andrade, itself from the name of a village), Mejía or Mexía (from the house of Mesía), Saavedra, Soutomaior (Hispanicized Sotomayor), Ulloa, Moscoso, Mariñas, Figueroa among others. Some of these families also served in Portugal, as the Andrade, Soutomaior or Lemos (who originated in Monforte de Lemos). As a result, these surnames are by now distributed all around the world.

The third group of surnames are the occupational ones, derived from the job or legal status of the bearer: Ferreiro ("Smith"), Carpinteiro ("Carpenter"), Besteiro ("Crossbow bearer"), Crego ("Priest"), Freire ("Friar"), Faraldo ("Herald"), Pintor ("Painter"), Pedreiro ("Stonemason"), Gaiteiro ("Bagpiper"); and also Cabaleiro ("Knight"), Escudeiro ("Esquire"), Fidalgo ("Nobleman"), Juiz ("Judge").

The fourth group includes the surnames derived from nicknames, which can have very diverse motivations:

a) External appearance, as eye colour (Ruso, from Latin roscidus, grey-eyed; Garzo, blue-eyed), hair colour (Dourado, "Blonde"; Bermello, "Red"; Cerviño, literally "deer-like", "Tawny, Auburn"; Cao, "white"), complexion (Branco, "White"; Pardo, "Swarth"; Delgado, "Slender") or other characteristics: Formoso ("Handsome"), Tato ("Stutterer"), Forte ("Strong"), Calviño ("Bald"), Esquerdeiro ("Left-handed").

b) Temperament and personality: Bonome, Bonhome ("Goodman"), Fiúza ("Who can be trusted"), Guerreiro ("Warlike"), Cordo ("Judicious").

c) Tree names: Carballo ("Oak"); Amieiro, Ameneiro ("Alder"); Freijo ("Ash tree").

d) Animal names: Gerpe (from Serpe, "Serpent"); Falcón ("Falcon"); Baleato ("Young Whale"); Gato ("Cat"); Coello ("Rabbit"); Aguia ("Eagle")

e) Deeds: Romeu (a person who pilgrimaged to Rome or the Holy Land)

Many Galician surnames have become Castilianized over the centuries, most notably after the forced submission of the Galician nobility obtained by the Catholic Monarchs in the last years of the 15th century.[30] This reflected the gradual spread of the Spanish language through the cities, in Santiago de Compostela, Lugo, A Coruña, Vigo and Ferrol, in the last case due to the establishment of an important base of the Spanish navy there in the 18th century.[31] For example, surnames like Orxás, Veiga, Outeiro, became Orjales, Vega, Otero. Toponyms like Ourense, A Coruña, Fisterra became Orense, La Coruña, Finisterre. In many cases this linguistic assimilation created confusion, for example Niño da Aguia (Galician: Eagle's Nest) was translated into Spanish as Niño de la Guía (Spanish: the Guide's child) and Mesón do Bento (Galician: Benedict's house) was translated as Mesón del Viento (Spanish: House of Wind).

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]

The oldest human occupation of Galicia dates to the Palaeolithic, when Galicia was covered by a dense oak temperate rain forest. The oldest human remains found, at Chan do Lindeiro, are from a woman who lived some 9,300 years ago and died because of a landslide, apparently while leading a pack of three aurochs; the genetic study of her remains revealed a woman that was an admixture of Western Hunter-Gatherer and Magdalenian people.[32] This type of admixture has been observed in France, also.[33]

Later on, some 6,500 years ago, a new population arrived from the Mediterranean, bringing agriculture and husbandry with them. Half of the woodland was razed to pasture and farmland, almost replacing all of the woodland some 5,000 years ago.[34] This new population also changed the landscape with the first permanent human structures, megaliths such as menhirs, barrows and cromlechs. During the Neolithic Galicia was one of the foci of Atlantic European Megalithic Culture,[35] putting in contact the Mediterranean and south Iberia with the rest of Atlantic Europe.[36]

Some 4,500 years ago a new culture and population arrived and presumingly admixed with the local farmers, the Bell beaker people, coming ultimately from the Pontic steppe, who introduced copper metallurgy and weaponry, and probably also new cultivars and breeds. Some scholars consider that they were the first people to bring Indo-European languages into Western Europe.[37] They lived in open villages, only protected by fences or ditches; local archaeologists consider that they caused a very large culture impact, replacing collectivism with individualism, as exemplified by their burial in individual cists, along with the reuse of old Neolithic tombs.[38] From this period and later dates a rich tradition of petroglyphs, which find close similarities in the British Isles, Scandinavia or northern Italy.[39] Motives include cup and ring marks, labyrinths, Bronze Age weaponry, deer and deer hunting, warriors, riders and ships.

- Early Bronze Age

-

Outeiro do cribo ('sieve's hill') labyrinth

-

Castriño de Conxo, Bronze Age weaponry

-

Laxe dos Carballos, deer hunting with leaf-shaped spears and cup and ring marks

-

Casota de Freáns, Vimianzo, a Bronze Age megalith with no corridor or tumulus

-

Caldas de Reis hoard, one of the largest in Western Europe, circa 1,800 BCE

-

Interior of a Bronze Age cabin (recreation), Campo Lameiro

During the Late Bronze Age and until 800-600 BCE the contacts with both southern Spain to the south, and Armorica and the Atlantic Isles to the north, intensified, probably fuelled by the abundance of local gold and metals such as tin,[40] which allowed the production of high quality bronze. It is at this moment that began the deposition or hoarding of prestige items, frequently in aquatic context. Also, during the Late Bronze Age a new type of ceremonial henge-like ring structures, of some 50 metres in diameter, are built all along Galicia.[41]

This period and interchange network, usually known as Atlantic Bronze Age, which appears to have had its centre in modern-day Brittany, was proposed by John T. Koch and Sir Barry Cunliffe as the one that originated Celtic languages —as a product of pre-existing and closely related Indo-European languages— which could have expanded along with the elite ideology associated with this cultural complex (Celtic from the west theory). Alleged difficulties with this theory and with pre-existing theories ("Celtic from the east") have led Patrick Simms-Williams to propose an intermediate "Celtic from the centre" theory, with an expansion of Celtic languages from the Alps during the Bronze Age.[42] A recent study shows the large scale admixture of an earlier population from Britain with people arriving probably from France during the late Bronze Age. These people, in the opinion of the authors, constitute a plausible vector for the expansion of Celtic languages into Britain, as no further Iron Age people movement of relevant scale is shown in their data.[43]

- Late Bronze Age

-

Late Bronze Age hoard of Samieira, unearthed in 1948 at some 50 metres from the seashore, and initially consisting of 152 palstaves

-

Bronze Age Galician swords, Museo de Pontevedra

-

Pedra Alta warrior stelle, Castrelo do Val

-

1. sword and girdle. 3. v-notch shield. 4. cart with horses

-

Horned-helmet figures

-

A rider

The Bronze Age - Iron Age transition (locally 1000-600 BCE) coincides with the hoarding of large quantity of bronze axes, unused, both in Galicia, Brittany, and southern Britain.[44] During this same transitional period, some communities began to protect their villages, settling in very protected areas where they built hill-forts. Among the oldest of these are Chandebrito in Nigrán,[45] Penas do Castelo in A Pobra do Brollón[46] and O Cociñadoiro in Arteixo, on a sea cliff and protected by a 3-metre-tall wall, it was also a metal factory, perhaps[47] dedicated to the Atlantic commerce,[48] all of them founded some 2,900-2,700 years ago. These earlier fortified settlements seem to be placed to control metallurgical resources and commerce. This transitional period is also characterized by the apparition of longhouses of ultimately north European tradition[49][50][51] which were replaced later in much of Galicia by roundhouses. By the 4th century BCE hill-forts have expanded all along Galicia, also on lowlands, soon becoming the only type of settlements.

These hill-forts were delimited usually by one or more walls; the defences also include ditches, ramparts and towers, and could define several habitable spaces. The gates were also heavily fortified. Inside, houses were originally built with perishable materials, with or without a stone footing; later on they were entirely made with stone walls, having up to two storeys. Specially in the south, houses or public spaces were adorned with carved stones and warrior sculptures. Stone heads, mimicking severed heads, are found at several locations and were perhaps placed near the gates of the forts. A number of public installations are known, for example saunas of probable ritual use.[52] Of ritual use and great value were also items such as bronze cauldrons, richly figured sacrificial hatchets[53] and gold torcs, of which more than a hundred exemplars are known.[54]

This culture is now known as Castro Culture; another characteristic of this culture is the absence of known burials: just exceptionally urns with ashes have been found buried at foundational sites, acting probably as protectors.

- Iron Age

-

Castromaior, Portomarín, Lugo

-

Castromaior's relief

-

Sauna of Punta dos Prados, Ortigueira

-

Sacrificial hatchet showing an ox, cauldron and torc

-

Short swords

-

Local ear pendants of ultimate Mediterranean origin

Occasional contacts with Mediterranean navigators, since the last half of the second millennium BCE,[55] became common after the 6th century BCE[56] and the voyage of Himilco. Punic importations from southern Spain became frequent along the coast of southern Galicia, although they didn't penetrate very far to the north or to the interior; also, new decorative motives, as the six-petal rosettes, are popularized, together with new metallurgical techniques and pieces (ear pendants) and some other innovations as the round hand mill. In exchange, Punics obtained tin, abundant in the islands and peninsulas of western Galicia (probable origin of the Cassiterides island myth)[57] and probably also gold. Incidentally, Avienus' Ora Maritima says after Himilco that the Oestrymni (inhabitants of western Iberia) used hide boats to navigate, an assertion confirmed by Pliny the Elder for the Galicians.[58]

Roman conquest

[edit]

First recorded contact with Rome happened during the Second Punic War, when Gallaecians and Astures, together with Lusitanians, Cantabrians and Celtiberians —that is, the major Indo-European nations of Iberia— figured among the mercenary armies hired by Hannibal to go with him into Italy. According to Silus Italicus's Punica III:[59]

Fibrarum, et pennæ, divinarumque sagacem

Flammarum misit dives Callæcia pubem,

Barbara nunc patriis ululantem carmina linguis,

Nunc, pedis alterno percussa verbere terra,

Ad numerum resonas gaudentem plaudere cætras.

Hæc requies ludusque viris, ea sacra voluptas.

Cetera femineus peragit labor: addere sulco

Semina, et inpresso tellurem vertere aratro

Segne viris: quidquid duro sine Marte gerendum,

Callaici conjux obit inrequieta mariti.

"Opulent Galicia sent her youth, expert in divination through the entrails of beasts, the flight of birds and the divine lightnings; sometimes they delight to chant rude songs in their fatherland's tongues, other times they make the ground tremble with alternative foot while happily clashing their caetra at the same time. This leisure and diversion is a sacred delight for the men, the feminine laboriosity do the rest: adding the seed to the furrow and working the ground with the plough while the men idle. Everything which must be done, with the exception of the hard war, is made restlessly by the wife of the Galician." He later also mentions the Grovii of southern Galicia and northwestern Portugal, with their capital Tui, apart from the other Galicians; other authors also marked the distinctness of the Grovii: Pomponius Mela by addressing that they were non Celtic, unlike the rest of the inhabitants of the coasts of Galicia; Pliny by signalling their Greek origin.[59]

After ending victoriously the Lusitanian war with the assassination of Viriathus, consul Caepio tried to wage war, unsuccessfully, on Gallaecians and Vettones, for the help they lent to the Lusitanians. In 138 BCE, another consul, Decimus Junius Brutus, in command of two legions, passed de Douro river and later the Lethes or Oblivio (Limia, which frightened his troops because of its other name), in a successful campaign, managing to conquer many places of the Galicians. After reaching the Minho river, and in his way back, he attacked (again successfully) the Bracari, who had been harassing his supply chain: Appian describe the Bracari women fighting bravely side by side with their men; of the women who were taken prisoners, some killed themselves, and others killed their children, preferring death to servitude.[59] The spoils of war allowed Decimus Junius Brutus to celebrate a triumph back in Rome, receiving the name Callaicus. Recently a very large marching Roman camp was discovered at high altitude, in Lomba do Mouro, at the very frontier of Galicia with Portugal. In 2021 a C-14 dating showed that it was built during the 2nd century BCE; since it is north of the Limia, it probably belonged to this campaign.[60]

The Roman contact had a very large impact on the Castro Culture: an increase in commerce with the south and the Mediterranean; adoption or development of sculpture and stone carving; the warrior ethos appear to increase in social importance;[61] some hill-forts are built new or rebuilt as true urban centres, oppida, with streets and definite public spaces, as San Cibrao de Las (10 ha) or Santa Trega (20 ha).[62]

- Oppida and Roman conquest

-

Gates of the oppidum of Saint Cibrao de Las

-

Aerial photo of San Cibrao de Las

-

Santa Tregra, A Guarda

-

Santa Trega with the Minho in the background

-

As minted circa 20 BCE during the conquest of Galicia, Asturia and Cantabria

-

Equitation scene, Formigueiro, Amoeiro

In 61 BCE Julius Caesar, commanding thirty cohorts, launched from Cádiz a maritime campaign along the Atlantic shores which ended in Brigantium. According to Cassius Dio, the locals, who had never seen a Roman fleet, surrendered in awe. Recent excavations at the Castro de Elviña hillfort, near A Coruña, have found both evidences of siege and partial destruction of the walls of the site, and also of a temple, dated to the middle of the first century BCE.[63]

Finally, in 29 BCE, Augustus launched a campaign of conquest against Gallaecians, Asturians and Cantabrians. The most memorable episode of this war was the siege on the Mons Medullius, who Paulus Orosius placed near the Minho river: it was surrounded by a 15 mille trench before a simultaneous Roman advance; according to Anneus Florus the besieged decided to kill themselves, by fire, sword, or by the venon of the yew tree.[64] Tens of Roman camps have been found related to this war, most of them corresponding to the later stages of the war, against Asturians and Cantabrians, some twenty of them in Galicia.[65] Augustus' victory over the Gallaecians is celebrated in the Sebasteion of Aphrodisias, Turkey, where a triumphal monument to Augustus mentions them[66] among other fifteen nations conquered by him. Also, the triumphal arch of Capentras probably represents a Gallaecian among other nations defeated by Augustus.[67]

Languages and ethnicity

[edit]

Pomponius Mela (a geographer from Tingentera, modern day Algeciras in Andalusia) described, circa 43 CE, the coasts of northwestern Iberia:[68]

Frons illa aliquamdiu rectam ripam habet, dein modico flexu accepto mox paululum eminet, tum reducta iterum iterumque recto margine iacens ad promunturium quod Celticum vocamus extenditur.

Totam Celtici colunt, sed a Durio ad flexum Grovi, fluuntque per eos Avo, Celadus, Nebis, Minius et cui oblivionis cognomen est Limia. Flexus ipse Lambriacam urbem amplexus recipit fluvios Laeron et Ullam. Partem quae prominet Praesamarchi habitant, perque eos Tamaris et Sars flumina non longe orta decurrunt, Tamaris secundum Ebora portum, Sars iuxta turrem Augusti titulo memorabilem. Cetera super Tamarici Nerique incolunt in eo tractu ultimi. Hactenus enim ad occidentem versa litora pertinent.

Deinde ad septentriones toto latere terra convertitur a Celtico promunturio ad Pyrenaeum usque. Perpetua eius ora, nisi ubi modici recessus ac parva promunturia sunt, ad Cantabros paene recta est.

In ea primum Artabri sunt etiamnum Celticae gentis, deinde Astyres. In Artabris sinus ore angusto admissum mare non angusto ambitu excipiens Adrobricam urbem et quattuor amnium ostia incingit: duo etiam inter accolentis ignobilia sunt, per alia Ducanaris exit et Libyca

"That ocean front for some distance has a straight bank, then, having taken a slight bend, soon protrudes a little bit and then it is drawn back, and again and again; then, lying on a straight line, the coast extends to the promontory which we call Celtic. All of it is inhabited by Celtics, except from the Durio until the bend, where the Grovi dwelt —and through them flow the rivers Avo, Celadus, Nebis, Minius and Limia, also called Oblivio—. On the bend there is the city of Lambriaca and the receding part receives the rivers Laeros and Ulia. The prominent part is inhabited by the Praestamarci, and through them flow the rivers Tamaris and Sars —which are born not afar— Tamaris by harbour Ebora, Sars by the tower of Augustus, of memorable title. For the rest, the Supertamarici and Neri inhabit in the last tract. Up to here what belongs to the western coast. From there all the coast is turned to the north, from the Celtic promontory to the Pyrenees. Its regular coast, except where there are small retreats and small headlands, is almost straight by the Cantabrians. On it first of all are the Artabri, still a Celtic people, then the Astures. Among the Artabri there is a bay which lets the sea through a narrow mouth, and encircles, not in a narrow circuit, the city of Adrobrica and the mouth of four rivers." The Atlantic and northern coast of today's Galicia was inhabited by Celtic peoples, with the exception of the southern extreme. Others geographers and authors (Pliny, Strabo), as well as the local Latin epigraphy, confirm the presence of Celtic peoples.

As for the language or languages spoken by the Galicians previously to their romanization, most scholars usually perceive a primitive Indo-European layer, another later one hardly distinguishable from Celtic and identifiable with Lusitanian, most notable in the south, the Gallaecia Bracarense (as a result, Lusitanian is sometimes called Lusitanian-Gallaecian) and finally Celtic proper; as stated by Alberto J. Lorrio:[69] "the presence of Celtic elements in the Northwest is indisputable, but there is no unanimity in considering whether there was an only Indo-European language in the West of Iberia, of Celtic kind, or either a number of languages derived from the arrival of non-Celtic Indo-Europeans first, and Celts later on". Some academic positions on this issue:

- Francesco Benozzo, proponent of the Palaeolithic continuity theory, considers that Celtic language is autochthonous in Galicia.[70] Since recent genetic studios show that European and Iberian Palaeolithic population was assimilated by larger migrant populations proceeding first from the Balkans and Anatolia, and later from Central Europe and ultimately from the Pontic steppe, this theory is probably flawed.

- For John T. Koch and Barry Cunliffe, proponent of the Celtic from the West theory, the Celtic language would have expanded during the late Bronze Age from the European Atlantic fringe, including Galicia, to the east.[71][72][73] For Patrick Simms-Williams, Celtic expanded from modern day France during the late Bronze Age.[42]

- Joan Coromines, lexicographer and author of the Diccionario crítico etimológico castellano e hispánico, considered that Galician language had a very important substrate attributable to at least two different Indo-European languages, an older non Celtic one who he derived from the Urnfield people and thought was present in most of northern Iberia, and another one he named Artabrian, the Celtic language of the Celts of Galicia.

- Blanca M. Prósper[74] and Francisco Villar defend that Lusitanian is a non Celtic Indo-European language related to Italic languages[75] because, in their opinion, the Indo-European aspirated stops have evolved into /f/ and /h/. At the same time, all along the area of this language, and specially in modern-day Galicia, a Celtic language was spoken; this language, a q-Celtic language similar to Celtiberian, is the Western Hispano-Celtic.[76][77]

- Joaquín Gorrochategui, José M. Vallejo,[78] Alberto J. Lorrio, García Alonso,[79] E. Luján[80] and others, consider that Lusitanian is not a Celtic language, but they don't consider it closer to Italic, neither, but part of a group of IE dialects which later evolved into Celtic, Italic and Lusitanian. On the other hand, Celtic speakers lived in close proximity to the Lusitanian. In this context, Gallaecia Bracarensis was clearly in communion with the Lusitania,[81] while Gallaecia Lucensis had its own Celtic profile.[82][83][84][85][86]

- Jürgen Untermann, continued by his disciple Carlos Búa,[87] defended that along the westernmost part of Iberia there was essentially just one language or group of languages, Gallaecian-Lusitanian or Lusitanian and Gallaecian, which in their opinion was definitely Celtic and not Italoid, as shown by the ending of dative plural (-bo, -bor < PIE -*bhos) and the evolution of the syllabic consonants, in particular -r̥- > -ri-.

- Local scholars and researchers of toponymy and lexicon of pre-Latin origin (J. J. Moralejo, Edelmiro Bascuas) saw at least two layers of Indo-Europeans: one early layer of a very primitive IE language which preserved p, most notable in river names, and a later Celtic layer.[88][89]

Roman period

[edit]

After the Roman conquest, the lands and people of northwestern Iberia were divided in three conventi (Gallaecia Lucensis, Gallaecia Bracarensis and Asturia) and annexed to the province of Hispania Tarraconensis.[90] Pliny wrote that the Lucenses comprised 16 populi and 166,000 free heads, and mentions the Lemavi, Albiones, Cibarci, Egivarri Namarini, Adovi, Arroni, Arrotrebae, Celtici Neri, Celtici Supertamarci, Copori, Celtici Praestamarci, Cileni among them (other authors mention also the Baedui, Artabri and Seurri); the Astures comprised 22 populi and 240,000, of whom the Lougei, Gigurri and Tiburi dwelt lands now in Galicia; finally the Bracarenses 24 civitates and 285,000, of whom the Grovi, Helleni, Querquerni, Coelerni, Bibali, Limici, Tamacani and Interamici dwelt, at least partially, in modern-day Galicia. The names of some of these peoples have been preserved as the names of regions, parishes and villages: Lemos < Lemavos, Cabarcos, Soneira < *Sub Nerii, Céltigos < Celticos, Valdeorras < Valle de Gigurris, Trives < Tiburis, Támagos < Tamacanos. Some other Galician regions derive from some populi or subdivision not listed by the classic authors, among them: Bergantiños < Brigantinos, from Briganti, Nendo < Nemetos, from Nemeton, Entíns < Gentinis ('the chieftains').[91]

A common characteristic of both Gallaecians and western Astures were their onomastic formula and social structure: while most of the other Indo-European peoples of Hispania used a formula such as:

- Name + Patronimic (gen. s.) + Gens / Family (gen. pl.), as, for example,

- Turaesius Letondicum Marsi f(ilius) : 'Turaesius son of Marsi, of the Letondi clan'

Gallaecians and western Astures used, until the 2nd century of our era, the formula:[92]

- Name + Patronimic (gen. s.) + [Populi/Civitas] (nom. s.) + [⊃] (abreviature of castellum) Origo (abl. s.) as:

- Nicer Clvtosi ⊃ Cavriaca Principis Albionum : Nicer, son of Clutosios, from castle Cauria, prince of the Albion

- Caeleo Cadroiolonis f(ilius) Cilenus ⊃ Berisamo : Cailio, son of Cadroilo, Cilenus from castle Berisamo

- Fabia Eburi f(ilia) Lemava ⊃ Eritaeco : Fabia, daughter of Eburios, Lemava from castle Eritaico

- Eburia Calueni f(ilia) Celtica Sup(ertamarca) ⊃ Lubri : Eburia, daughter of Calugenos, Celtica Supertamarca from castle Lubris

- Anceitus Vacc[e]i f(ilius) limicus ⊃ Talabrig(a) : Anceitos, son of Vacceos, Limicus from castle Talabriga

The known personal names used by locals in northern Gallaecia were largely Celtic:[93] Aio, Alluquius, Ambatus, Ambollus, Andamus, Angetus, Arius, Artius, Atius, Atia, Boutius, Cadroiolo, Caeleo, Caluenus, Camalus, Cambauius, Celtiatus, Cloutaius, Cloutius, Clutamus, Clutosius, Coedus, Coemia, Coroturetis, Eburus, Eburia, Louesus, Medamus, Nantia, Nantius, Reburrus, Secoilia, Seguia, Talauius, Tridia, Vecius, Veroblius, Verotus, Vesuclotus, among others.

Three legions were stationed near the Cantabrian mountains after the war, later reduced to the Legio VII Gemina in León, with three auxiliary cohorts in Galicia (the Cohors I Celtiberorum in Ciadella, Sobrado dos Monxes, near Brigantium; other unity at Aquis Querquennis, and another one near Lucus Augusti) and others elsewhere. Soon Roma began to recruit auxiliary troops locally: five cohorts of Gallaecians from the conventus Lucenses, other five of bracarenses, two mixed ones of Galicians and Asturians, and an ala and cohort of Lemavi.[94][95]

Also, Gallaecia and Asturia became the most important producers of gold on the Empire: according to Pliny Lusitania, Gallaecia and, especially, Asturia, produced the equivalent to 6,700 kg per year. It has been estimated that the eight hundred Roman gold mines known in Galicia produced in total in between 190,000 and 2,000,000 kg.[96]

-

Reenactors at Lugo's Arde Lucus

-

Roman camp of Aquis Querquennis

-

Nicer Clutosi's stelle

-

Apana Amboli's stele

-

Tabula hospitalis from Carbedo

-

Romanized hill-fort of Viladonga, Castro de Rei

During the Diocletian reforms, late third century, Gallaecia was upgraded to province.

Germanic era: 5th – 8th centuries

[edit]In 409 the Vandals, Suebi and Alans, who had entered in the Roman Empire in 405 or 406 crossing the Rhin, passed into the Iberian Peninsula. After a year of war and plundering, they were pacified by the offering of lands where to settle. The Roman province of Gallaecia (including Gallaecia proper and the regions of Asturia and Cantabria) were assigned to the Suebi and the Hasding Vandals. Both groups clashed soon, in 419, and so the Vandals left to southern Iberia, where they incorporated the last remnants of Alans and Silingi Vandals, who had been crushed by Rome in previous years. In 429 the Vandals left for Africa.[97][98]

In 430 a long term conflict broke in between the Suebi and locals who chronicler Hydatius called gallaecos (i.e. galegos, the endonym of modern-day Galicians) and, initially, plebs ("folk, common people"), in contrast with whom he called romani: the rural landowners in Lusitania and the inhabitants of the cities. Soon, among those Galicians, appear also local noblemen and churchmen. As the Britons in southern Great Britain, the Galician were forced to act autonomously from Rome, exercising home rule.[99] They reoccupied old Iron Age hill-forts and built new strongholds and fortification all along Galicia;[100] the largest known today are at Mt. Pindo,[101] Mt. Aloia[102] and at Castro Valente.[103] These fortresses were later used by locals against Visigoths, Arabs and Norsemen. In this conflict in between Galicians and Suebi, Rome and local bishops acted frequently rather as intermediaries than as a part, and peace our truce was obtained or warranted with the interchange of prisoners and hostages.[97][104]

In 438 both people attained a peace that would last for twenty years; by then old king Hermeric, who had led their people at least since their arrival from Central Europe, ceded the crown to his son Rechila, who would expand the kingdom to the south and east, conquering Emerita Augusta, Mértola and Seville, and moving his troops into eastern Hispania, defeating both Roman and Visigoth armies along the way. His successor and son, Rechiar, converted from paganism to Catholicism upon being crowned, and married a Visigoth princess. He negotiated with Rome a new status for his kingdom and became the first post-Roman Germanic king to mint coins in his name.[105] Soon, he tried to expand into the last Roman province in Hispania, Tarraconense; eventually this led to open conflict with Rome and the Visigoths. In 456 a large army of foederati commanded by the kings of the Visigoths and the Burgundians entered Hispania and defeated the Suebi army near the city of León. Rechiar fled to Porto, but he was captured and later executed. Notwithstanding, the Visigoths left in a hurry the theatre of operation, returning to France. That allowed the Suebi to regroup. After a period of petty-kings rivalry, accompanied by devastation and pillage on Galicians, Remismund was recognized as only and legitimate king by the Suebi, and accepted by the Visigoths; he also promoted the Arianism among the Suebi. As result, the Suebi kingdom came to its limits, encompassing modern day Galicia, northern Portugal until Coimbra, and large parts of Asturias, León and Zamora.[105]

The chronicle of Hydatius also records naval raids of both Vandals and Heruli on the Galician coasts during the 5th century.[97]

Medieval era

[edit]In 718 the area briefly came under the control of the Moors after their conquest and dismantling of the Visigothic Empire, but the Galicians successfully rebelled against Moorish rule in 739, establishing a renewed Kingdom of Galicia which would become totally stable after 813 with the medieval popularization of the "Way of St James".

Geography and demographics

[edit]

Political and administrative divisions

[edit]The autonomous community, a concept established in the Spanish constitution of 1978, that is known as (a) Comunidade Autónoma Galega in Galician, and as (la) Comunidad Autónoma Gallega in Spanish (in English: Galician Autonomous Community), is composed of the four Spanish provinces of A Coruña, Lugo, Ourense, and Pontevedra.

Population, main cities and languages

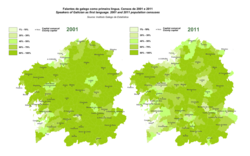

[edit]The official statistical body of Galicia is the Instituto Galego de Estatística (IGE). According to the IGE, Galicia's total population in 2008 was 2,783,100 (1,138,474 in A Coruña,[106] 355.406 in Lugo,[107] 336.002 in Ourense,[108] and 953.218 in Pontevedra[109]). The most important cities in this region, which serve as the provinces' administrative centres, are Vigo (in Pontevedra), Pontevedra, Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña, Ferrol (in A Coruña), Lugo (in Lugo), and Ourense (in Ourense). The official languages are Galician and Spanish. Knowledge of Spanish is compulsory according to the Spanish constitution and virtually universal. Knowledge of Galician, after declining for many years owing to the pressure of Spanish and official persecution, is again on the rise due to favorable official language policies and popular support.[citation needed] Currently about 82% of Galicia's population can speak Galician[110] and about 61% have it as a mother tongue.[11]

Culture

[edit]Celtic revival and Celtic identity

[edit]

In the 19th century a group of Romantic and Nationalist writers and scholars, among them Eduardo Pondal and Manuel Murguía,[111] led a Celtic revival initially based on the historical testimonies of ancient Roman and Greek authors (Pomponius Mela, Pliny the Elder, Strabo and Ptolemy), who wrote about the Celtic peoples who inhabited Galicia;[112] but they also based this revival in linguistic and onomastic data,[113][114] and in the similarity of some aspects of the culture and the geography of Galicia with that of the Celtic countries as Ireland, Brittany and Britain, as well as in the Bronze and Iron Age archaeological cultures.[115][116] These similarities included legends and traditions,[117] and decorative and popular arts and music.[118] It also included the green hilly landscape and the ubiquity of Iron Age hill-forts, Neolithic megaliths and Bronze Age cup and ring marks, which were and are popularly seen as "Celtic", also among foreigners who travelled to Galicia.[119][120][121]

As a Celtic region of Spain, Galicia has a tartan called Galicia National.[122]

During the late 19th and early 20th century this revival permeated Galician society: in 1916 Os Pinos, a poem by Eduardo Pondal, was chosen as the lyrics for the new Galician hymn. One of the strophes of the poem says: Galicians, be strong / ready to great deeds / align your breast / for a glorious end / sons of the noble Celts / strong and traveller / fight for the fate / of the homeland of Breogán.[123] The Celtic past became an integral part of the self-perceived Galician identity:[124] as a result an important number of cultural association and sport clubs received names related to the Celts, among them Celta de Vigo, Céltiga FC, CB Breogán, etc.

From the 1970s on a series of Celtic music and cultural festivals were also popularized, the most notable being the Festival Internacional do Mundo Celta de Ortigueira, at the same time that Galician folk musical bands and interpreters became usual participants in Celtic festivals elsewhere, as in the Interceltic festival of Lorient, where Galicia sent its first delegation in 1976.[125]

- Celtic and non Celtic elements common along the western Atlantic coast of Europe which are popularly perceived as Celtic.

-

A castro (hill-fort) at Baroña, Porto do Son

-

Medieval interlaced cross, Santiago de Compostela

-

Triskelion from the Museo de Ourense

-

View of the hillfort at San Cibrao de Las, Ourense

-

The rocky and misty coast of Cabo Silleiro, Baiona

Folklore and traditions

[edit]

Myths and legends

[edit]

Galician folklore is similar to that of the rest of western Europe, especially to that or northern Portugal, Asturias and Cantabria. Among its most notable myths are the following:[126]

- Before the world was inhabited by humans, animals could speak: many traditional tales about animals begin with the phrase aló cando os animais falaban, 'back then, when animals used to speak', which has become equivalent to English once upon a time.

- Our world is connected to an underworld dwelt by the mouros ('the dark ones' or perhaps 'the dead ones', mistaken by Andalusian Moors in many tales), an ancient and sombre race who inhabited the upper world before ourselves and who dislike humans. They can still travel to our world to interact with us through the ruins of the places they built or inhabited, such as barrows, dolmens, stone circles, hill-forts, etc., which are still traditionally called with names such as Eira dos Mouros ('Mouros' threshing floor'), Casa dos Mouros ('Mouros' house'), Forno dos Mouros ('Mouros' oven'). This kind of place names are already attested in Latin documents dating to circa 900 CE and later. Humans can also travel to the underworld, either becoming very rich or suffering for their greed as a result. Some mouros or encantos can appear as tall and strong men riding large horses and there are specific spells to ask them for riches.

- Fairies and nymphs (who also belong to the netherworld) receive many names, among them mouras, encantos ('apparition; spell'), damas ('ladies'), madamas ('miladies'), xás (from Latin dianas). They are frequently portrayed as women of incredible beauty and riches and long golden blonde hair that can be found by the aforementioned prehistoric ruins or at fountains and ponds, where they comb their hair. Other times, they are gigantic women of incredible strength, enough to move massive boulders, who can be found with a spinning distaff or a baby.[127] Under this appearance they are the same with the Vella ("the Old Lady"), who is somehow also responsible for the weather: the rainbow is called arco da vella in Galician ("Old Lady's bow"), a myth which is probably related to the Cailleach, 'Old Woman', 'Hag', of Ireland and Scotland.[128]

- Lavandeiras (washerwomen) are eerie fairies that are found at a river of pond washing clothes, under the aspect of women, especially at night. They can ask a passer-by to help twist the clothes: if the passer-by mistakenly twists in the same direction, the clothes turn into blood.[126]

- The trasnos, tardos or trasgos (goblins) are mischievous, household creatures, who like to annoy and confound people. They can cause nightmares by siting on the chest of the people, move things and cause other troubles. In Galician trasnada (~'goblin-ery') means 'trick, mischief'.

- Other sign of the netherworld is the apparition of a golden hen followed by his golden chicks (a galiña dos pitos de ouro), which, no matter how hard one tries, can't be caught. There is a similar myth in Bulgaria.

- Maruxaina was a vicious siren who lived near the town of San Cribrao and who eventually was captured and executed by the locals.

- The barrows are also inhabited by other entities called ouvas ('elfs').

- Other beings with control of the weather are the nubeiros ('cloud-ers'). George Borrow in his book The Bible in Spain narrates how he met a nubeiro while travelling Galicia circa 1835.[129] Other similar beings are the tronantes and escoleres.

- Many lakes are believed to be the result of the drowning of ancient cities (frequently called Lucerna, Valverde, 'Green Valley', or Antiochia in tales and legends) when the inhabitants failed to give shelter to Jesus or a saint, or when a king of the mouros used his magic out of spit. Some nights the city's bells can still be heard.[126] This legend was first recorded in the 12th century Codex Calixtinus and in that version is Charlemagne who prays God and Saint James to drown a Moor city reluctant to commit to him.[130] This myth appear to be related to the Breton myth of Ys.

- Another mythical being associated with drowned cities is the boi bruador, a bellowing ox which can be heard at night near lakes, a legend first recorded circa 1550.[126]

- Olláparos are giants similar to cyclopes who sometimes have also an eye on the back of the head.[126] They are related to the Cantabrian Ojáncanu.

- Bruxas and meigas (witches) can take the form of animals. In particular, the chuchonas ('suckers') can take the form of a blowfly to feed on the blood of babies and children, causing anaemia.

- Lobishomes (werewolves) are humans who sometimes turn into wolves because of a curse.[131] Manuel Blanco Romasanta was a Galician serial killer sentenced to death in 1853 for thirteen assassinations. His legal defence was based in his condition of werewolf as consequence of a curse.[132]

- Anciently, there were giant serpents (serpe, there's a mountain range called Cova da Serpe, 'Sepents' dem', so named since at least the 10th century), some of them winged, and dragons (dragón) which could feed on cattle. On the legend of the transfer of the body of Saint James from the Holy Land to Galicia, recorded in the 12th century Codex Calixtinus, the local queen, Queen Lupa, commanded the disciples of Saint James to go grab a pair of meek oxen she had by the hill known as Pico Sacro ("Sacred Peak"), where a dragon dwelt, with the hope that either the dragon or the oxen (which were actually fierce bulls) would kill them.[130] There were also cocas (cockatrices), which were taken out in procession in certain dates, as attested since 1437.[126] In the town of Redondela this procession is still held each year.

- The compaña ('retinue'), hoste ('army'), estantiga ( < hoste antiga, 'anciente army'), Santa Compaña ('holy retinue') is the local version of the wild hunt. In its modern form is a nocturne procession of the dead, who, porting candles or torches, and frequently a coffin, announce the imminent decease of a neighbour. This procession can "capture" a living person, who is then obliged to precede the Santa Compaña all night long, through forest, streams and brambles, or until another one takes his place. One can protect himself from being taken by the Compaña by tracing a circle and getting inside it, or by throwing oneself to the ground and ignoring the Compaña while it passes over. A solitary phantom related to the Compaña is the estadea. This myth is also related to the fairy host in Ireland, sluagh in Scotland and toili in Wales.[117]

- The urco (güercu in Asturias) is a giant black dog who emerges from the sea or from a river to cause terror to the locals. They are also, per se, a bad omen.[133]

Traditions and beliefs

[edit]While Galicia was traditionally a profoundly Catholic society, in its beliefs there are many remnants of previous religious systems, in particular the belief on a pantheon of gods, now saints; in the reincarnation in form of an animal, when there are unfinished business; the evil eye and the sickness caused by curses; the holiness of crossroads and fountains, etcetera. The first attestation of the beliefs of the Galicians in a Christian context is offered by the Pannonian Martin of Braga who in his letter De Correctione Rusticorum condemns, among others, the belief in the Roman gods or in the lamias, nymphs and dianas, and also in practices as putting candles to trees, springs and crossroads.

- Sanctuaries are socially important places for pilgrimage (romaría) and devotion, each one under the protection of a saint or virgin Mary. There are different beliefs associated with each one: the sanctuary of Santo André de Teixido in Cedeira is associated with reincarnation, as it is said that a Santo André de Teixido vai de morto o que non foi de vivo ('to Saint Andrew at Teixido —yew-tree-copse— goes as dead the ones that didn't went while alive'). It is advised not to kill lizards or any other animal while in the vicinity. The Corpiño sanctuary near Lalín and San Campío near Tomiño are associated with the treatment of mental illness and evil eye or meigallo. Virxe da Barca in Muxía is built by the place where it is said that Mary arrived aboard a stone boat, a recurring myth in Galicia also present in Ireland and Brittany.[134] Many of these places were probably built over pagan cult places.

- High crosses and calvaries, locally named cruceiros or peto de ánimas, are usually placed at crossroads, before sacred places, or marking a pilgrimage road. Placing flowers or lit candles before that monuments are common practices. In 1996 the Galician community in Ushuaia, Argentine, the southernmost city on the world, built a cruceiro with the legent 'Galicia shines in this land's end'.

- Sanctuaries, cruceiros and petos de ánimas

-

Virxe da Barca, Muxía

-

Santo André de Teixido, Cedeira

-

Peto de ánimas, crossroad of Moldes, Pobra do Caramiñal

-

Calvario at Castro Barbudo, Ponte Caldelas

-

Cruceiro do Hío, Cangas do Morrazo

-

Cruceiro at Muros

- Traditional medicine was administered by menciñeiros and menciñeiras, who used both herbs and spells to treat illness. Also compoñedores and compoñedoras: healers specialized in mending bones and joints.

Popular feasts

[edit]Aside from Catholic feasts and celebrations, there are other annual celebrations of pagan or mixed origin:

- Entroido (Shrovetide, Carnival). The Entroido ('entering; prelude') is usually a period of indulgence and feasts, which contrast with the soberness of the Holy Week and Easter. Parades and festivals (which were prosecuted by the Catholic Church) are held all along Galicia and, specially in Ourense, masks such as the peliqueiros, cigarróns, boteiros, felos, pantallas, who can commit minor mischiefs to other attendants, are central to the celebrations.

- Noite de San Xoán (Saint John's eve). Saint John's eve is celebrated around bonfires which are lit at dusk; young people jump over the fire three, seven or nine times. Other traditions associated to this night is the nine-waves bath in the beach, for having children,[135] and the preparation of the auga de San Xoán (Saint John's water) by letting a bowl with a mixture of selected herbs outdoors all night. This water is used to wash one's face in the morning.

- Rapa das bestas.

- Feasts

-

Entroido: Peliqueiros of Laza, Ourense

-

Boteiros, Viana do Bolo

-

Traditional filloas, crepe-like pancakes

-

Pantallas from Xinzo de Limia

-

Carantoñas, Chantada

-

San Xoán

-

Aloitadores, Rapa das bestas

Traditional costume

[edit]Traditional Galician costume, as understood today, got conformed fundamentally during the second half of the 18th century. Notwithstanding, some very characteristic elements, as the monteira (an embroidered felt hat), breeches and jacket are already present in 16th century depictions.[136] Although there are some regional variance, males attire is generally composed of monteira and sometimes pano (headcloth), camisa (shirt), chaleco (vest), chaqueta (jacket), faixa (sash), calzón (breeches), cirolas (underwear), polainas (gaiters, spats) and zocas, zocos (clogs or boots).[136]

- Men's traditional costume

-

Musicians, c. 1900

-

A Galician, 1874

-

A bagpiper with monteira (hat)

-

An old man in traditional attire

-

Zocas

-

Polainas

Female costume was composed of cofia (coif) or, later, pano (headcloth); dengue (short cape worn as a jacket) or corpiño (bodice); camisa (shirt), refaixo (petticoat), saia (skirt), mantelo (apron) and faltriqueira (pouch or bag).[136]

- Women's traditional costume

-

Old lady with cofia

-

Galician woman with embroidered mantelo and saffron faldriqueira

-

Galician woman by Serafín Avendaño, 1891. She's wearing a dengue

-

Dancing

-

Zocos

-

At Pontevedra

-

Going to the fountain by Alfredo Souto Cuero, 1893.

Traditional music

[edit]The most characteristic instrument in traditional music is probably the gaita (bagpipe). The gaita have a conical double-reed chanter, and usually have one to four drones.[137] The bag is usually inflated through a blowpipe, but in the gaita de barquín it is inflated by the operation of a bellows. In the past the gaita was usually accompanied just by tamboril (snare drum) and bombo or caixa (bass drum), but since the middle of the twentieth century the groups and bands have become very popular. Pieces which are usually interpreted with gaita are the muiñeira, often in 6

8 time and very similar to Irish jigs;[138] the alborada, played during the early mornings of holydays; the marcha (march) which accompanies processions and retinues. Some renowned compositions are the 19th century Muiñeira de Chantada and the traditional Aires de Pontevedra (an alborada) and Marcha do Antigo Reino de Galicia (March of the Old Kingdom of Galicia).

Another very representative instrument is the pandeireta (tambourine), which along or together with other drums as the pandeiro, castanets, etc., usually accompanied the songs and celebrations of the working women and men during the seráns (evenings), foliadas or fiadas.

Other genres include de alalá, which can be sung a cappella, or the cancións de cego (blindman's songs), interpreted with violin of zanfoña.

- Galician musics and dancers

-

Bagpiper with a gaita de barquín and musicians with a pandeireta and tamboril

-

circa 1900: famous piper O Rilo

-

Bagpiper, 13th century, Cantigas de Santa Maria

-

Dancing a muiñeira

-

1927: Os gaiteiros de Soutelo

-

Musician Faustino Santalices

-

Pandereiteiras de Mens

Literature

[edit]-

Rosalia de Castro was one of the most representatives authors of the Rexurdimento (revival of the Galician language).

-

Eduardo Pondal, considered himself a "bard of freedom", he imagined a Celtic past of freedom and independence, which he tried to recover for Galicia with his poetry.[139]

-

Manuel Curros Enríquez, a Galician journalist and writer who was famous for his compromise with the Republicanism against the Spanish Monarchy as well.

-

Manuel Rivas was born in A Coruña. A famous Galician journalist, writer and poet whose work is the most widely translated in the history of Galician literature.

Painting, plastic arts and architecture

[edit]-

Painter Luís Seoane

-

Sculptor Francisco Asorey

-

Architect Antonio Palacios

Science

[edit]-

Benito Jerónimo Feijóo y Montenegro was a monk and scholar who wrote a great collection of essays that cover a range of subjects, from natural history and the then known sciences.

-

Martin Sarmiento. He wrote on a wide variety of subjects, including Literature, Medicine, Botany, Ethnography, History, Theology, Linguistics, etc.

Music

[edit]-

Tanxugueiras are a Galician folk trio formed in 2016. The group aim to bring a modern sound to traditional Galician music by merging folk sounds with pop and world music influences. Their music focuses on themes such as the understanding between peoples, the defence of the Galician language and culture, and women's empowerment.

-

Carlos Núñez is currently one of the most famous Galician bagpipers, who has collaborated with Ry Cooder, Sharon Shannon, Sinéad O'Connor, The Chieftains, Altan among others.

-

Susana Seivane is a Galician bagpiper. She was born into a family of well-known Galician luthiers and musicians (The Seivane).

-

Carlos Jean is a DJ and record producer. He was born in Ferrol, of Haitian and Galician heritage.

Sport

[edit]-

Francisco Javier Gómez Noya (1983-), former triathlete, Silver in 2012 Summer Olympics.

-

Óscar Pereiro is a professional road bicycle racer. Pereiro won the 2006 Tour de France.

-

David Cal Figueroa is a Galician sprint canoer who has competed since 1999, he became the athlete with the most Olympic medals of all time in Spain.

-

Ana Peleteiro is a triple jumper and the current national record holder. She won the gold medal in the 2019 European Athletics Indoor Championships.[140]

Cinema and TV

[edit]-

María Castro (1981-) is a well-known Galician actress who performed in several Spanish TV series and movies.

-

Luis Tosar has starred in some successful Spanish movies such as Celda 211 or Te doy mis ojos.

-

Oliver Laxe is a French-born Galician director whose third film, Fire Will Come, became the most watched and most successful Galician film in history.

-

Maria Casarès was one of the most distinguished stars of the French stage and cinema.

-

Pedro Alonso is best known for his role of Andrés "Berlin" de Fonollosa in the Spanish series Money Heist (La casa de papel).

People of Galician origin

[edit]-

Cuban former leader Fidel Castro

-

Caudillo and dictator of Spain, Francisco Franco

-

Portuguese explorer João da Nova

-

American actor Martin Sheen, born Ramón Estévez

-

Brazilian writer Nélida Piñon

-

Argentinian ex-president Raúl Alfonsín

-

José Alonso y Trelles, Uruguayan poet

-

Laurentino Cortizo Cohen, president of Panama

-

Tabaré Vázquez, ex-president of Uruguay

-

Mariano Rajoy, former Prime Minister of Spain

-

Santiago Casares Quiroga, ORGA's founder and former Prime Minister of Spain

-

George A. Romero, American cinematographer

See also

[edit]- List of Galician people

- Galician nationalism

- Fillos de Galicia

- Galician diaspora

- Spanish people

- Nationalities and regions of Spain

References

[edit]- ^ Sum of the inhabitants of Spain born in Galicia (c. 2.8 million), plus Spaniards living abroad and inscribed in the electoral census (CERA) as electors in one of the four Galician constituencies.

- ^ a b c d e f g Not including Galicians born outside Galicia

- ^ a b c d e f g "Instituto Nacional de Estadística". Ine.es. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "INE – CensoElectoral". Ine.es. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ Internacional, La Región (30 July 2015). "Miranda visita Venezuela para conocer las preocupaciones de la diáspora gallega". La Región Internacional. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Interactivo: Creencias y prácticas religiosas en España". Lavanguardia.com. 2 April 2015. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 179, 776. ISBN 0-313-30984-1. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

other Celtic peoples ... Galicians ...; ... Romance (Latin) nations ... Galicians

- ^ Recalde, Montserrat (1997). La vitalidad etnolingüística gallega. València: Centro de Estudios sobre Comunicación Interlingüistíca e Intercultural. ISBN 978-84-370-2895-8.

- ^ Bycroft, C.; Fernandez-Rozadilla, C.; Ruiz-Ponte, C.; Quintela, I.; Donnelly, P.; Myers, S.; Myers, Simon (2019). "Patterns of genetic differentiation and the footprints of historical migrations in the Iberian Peninsula". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 551. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..551B. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08272-w. PMC 6358624. PMID 30710075.

- ^ Recalde, Montserrat (1997). La vitalidad etnolingüística gallega. València: Centro de Estudios sobre Comunicación Interlingüistíca e Intercultural. ISBN 978-84-370-2895-8.

- ^ a b "Persoas segundo a lingua na que falan habitualmente. Ano 2003". Ige.eu. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 788–791. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- ^ Falileyev, Alexander; Gohil, Ashwin E.; Ward, Naomi; Briggs, Keith (31 December 2010). Dictionary of Continental Celtic Place-Names: A Celtic Companion to the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. CMCS Publications. ISBN 978-0-9557182-3-6. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 19 July 2021., s.v. Callaeci.

- ^ Luján, Eugenio (2009). "Pueblos celtas y no celtas de la Galicia antigua: fuentes literarias frente a fuentes epigráficas". Real Académia de Cultura Valenciana: Sección de estudios ibéricos "D. Fletcher Valls". Estudios de lenguas y epigrafía antiguas (9): 219–250. ISSN 1135-5026. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ a b Moralejo, Juan J. (2008). Callaica nomina: estudios de onomástica gallega (PDF). A Coruña: Fundación Pedro Barrié de la Maza. pp. 113–148. ISBN 978-84-95892-68-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "9.17. Title for image of people of the Callaeci". IAph. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Búa, Carlos (2018). Toponimia prelatina de Galicia. Santiago de Compostela: USC. p. 213. ISBN 978-84-17595-07-4. Archived from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ Curchin, Leonard A. (2008) Estudios Gallegos The toponyms of the Roman Galicia: New Study Archived June 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. CUADERNOS DE ESTUDIOS GALLEGOS LV (121) p. 111

- ^ Benozzo, F. (2018) Uma paisagem atlântica pré-histórica. Etnogénese e etno-filologia paleo-mesolítica das tradições galega e portuguesa, in proceedings of Jornadas das Letras Galego-Portuguesas 2015–2017, DTS, Università di Bologna and Academia Galega da Língua Portuguesa, pp. 159-170.

- ^ Pierre-Yves Lambert, Histoire de la langue gauloise, éditions Errance, 1994, p. 99 - 194

- ^ a b LAMBERT 191

- ^ Xavier Delamarre, Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise, Errance, 2003, p. 98-99

- ^ DELAMARRE 98 - 99

- ^ Fernando Cabeza Quiles, Toponimia de Galicia, Editorial Galaxia, 2008, p. 301 - 302 - 303 (read online in Galician)[1] Archived 22 November 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Galician". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ a b de Azevedo Maia, Clarinda (1986). História do Galego-Português. Estado linguistico da Galiza e do Noroeste de Portugal desde o século XIII ao século XVI. Coimbra: Instituto Nacional de Investigação Científica.

- ^ For this section: Boullón Agrelo, Ana Isabel (2007). "Aproximación á configuración lingüística dos apelidos en Galicia". Verba: Anuario Galego de Filoloxia (34): 285–309. ISSN 0210-377X. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Cf. Ana Isabel Boullón Agrelo / Xulio Sousa Fernández (dirs.): Cartografía dos apelidos de Galicia. Santiago de Compostela: Instituto da Lingua Galega.

- ^ Daponte, Vasco (1986). Recuento de las casas antiguas del reino de Galicia (in Spanish). Equipo de Investigación "Galicia hasta 1500". Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia, Consellería da Presidencia, Servicio Central de Publicacións. ISBN 84-505-3389-9. OCLC 21951323.

- ^ Mariño Paz, Ramón (1998). Historia da lingua galega (2 ed.). Santiago de Compostela: Sotelo Blanco. pp. 195–205. ISBN 84-7824-333-X.

- ^ Mariño Paz, Ramón (1998). Historia da lingua galega (2 ed.). Santiago de Compostela: Sotelo Blanco. pp. 225–230. ISBN 84-7824-333-X.

- ^ Villalba-Mouco, Vanessa; van de Loosdrecht, Marieke S.; Posth, Cosimo; Mora, Rafael; Martínez-Moreno, Jorge; Rojo-Guerra, Manuel; Salazar-García, Domingo C.; Royo-Guillén, José I.; Kunst, Michael; Rougier, Hélène; Crevecoeur, Isabelle; Arcusa-Magallón, Héctor; Tejedor-Rodríguez, Cristina; García-Martínez de Lagrán, Iñigo; Garrido-Pena, Rafael; Alt, Kurt W.; Jeong, Choongwon; Schiffels, Stephan; Utrilla, Pilar; Krause, Johannes; Haak, Wolfgang (2019). "Survival of Late Pleistocene Hunter-Gatherer Ancestry in the Iberian Peninsula". Current Biology. 29 (7): 1169–1177.e7. Bibcode:2019CBio...29E1169V. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.006. hdl:10261/208851. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 30880015. S2CID 76663708.

- ^ Brunel, Samantha; Bennett, E. Andrew; Cardin, Laurent; Garraud, Damien; Barrand Emam, Hélène; Beylier, Alexandre; Boulestin, Bruno; Chenal, Fanny; Ciesielski, Elsa; Convertini, Fabien; Dedet, Bernard; Desbrosse-Degobertiere, Stéphanie; Desenne, Sophie; Dubouloz, Jerôme; Duday, Henri; Escalon, Gilles; Fabre, Véronique; Gailledrat, Eric; Gandelin, Muriel; Gleize, Yves; Goepfert, Sébastien; Guilaine, Jean; Hachem, Lamys; Ilett, Michael; Lambach, François; Maziere, Florent; Perrin, Bertrand; Plouin, Suzanne; Pinard, Estelle; Praud, Ivan; Richard, Isabelle; Riquier, Vincent; Roure, Réjane; Sendra, Benoit; Thevenet, Corinne; Thiol, Sandrine; Vauquelin, Elisabeth; Vergnaud, Luc; Grange, Thierry; Geigl, Eva-Maria; Pruvost, Melanie (9 June 2020). "Ancient genomes from present-day France unveil 7,000 years of its demographic history". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (23): 12791–12798. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11712791B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1918034117. eISSN 1091-6490. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7293694. PMID 32457149.

- ^ Criado-Boado, Felipe; Parcero-Oubiña, César; Otero Vilariño, Carlos; Aboal-Fernández, Roberto; Ayán Vila, Xurxo; Barreiro, David; Ballesteros-Arias, Paula; Cabrejas, Elena; Costa-Casais, Manuela; Fábrega-Álvarez, Pastor; Fonte, João; Gianotti, Camila; González-García, A. César; Güimil-Fariña, Alejandro; Lima Oliveira, Elena; López Noia, Raquel; Mañana-Borrazás, Patricia; Martínez Cortizas, Antonio; Millán Lence, Matilde; Rodríguez-Paz, Anxo; Santos Estévez, Manuel (2016). Atlas arqueolóxico da paisaxe galega. Xerais. p. 48. hdl:10261/132739. ISBN 978-84-9121-048-1. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Benozzo, F. (2018): "Uma paisagem atlântica pré-histórica. Etnogénese e etno-filologia paleo-mesolítica das tradições galega e portuguesa", in proceedings of Jornadas das Letras Galego-Portugesas 2015–2017. Università de Bologna, DTS and Academia Galega da Língua Portuguesa. pp. 159-170

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry W. (2008). Europe between the oceans: themes and variations, 9000 BC - AD 1000. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11923-7.

- ^ John T. Koch; Barry W. Cunliffe, eds. (2013). Celtic from the West 2: rethinking the Bronze Age and the arrival of Indo-European in Atlantic Europe. Celtic studies publications. Oxford, UK; Oakville, CT: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-529-3.

- ^ de la Peña Santos, Antonio (1 July 2003). Galicia. Prehistoria. Castrexo e primeira romanización. Vigo. pp. 61ss. ISBN 978-84-96203-29-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bradley, Mr Richard; Bradley, Richard (2002). Rock Art and the Prehistory of Atlantic Europe: Signing the Land. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-44699-7. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (1999). "Atlantic Sea-ways". Revista de Guimarães. especial - Actas do Congresso de Proto-História Europeia: 93–105. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Rodríguez, Ana (26 December 2021). "Henges, círculos invisibles de la Edad de Bronce". Faro de Vigo. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ a b An Alternative to 'Celtic from the East' and 'Celtic from the West', Patrick Sims-Williams, Cambridge University Press, 2020 [2] Archived January 12, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Patterson, Nick; et al. (January 2022). "Large-scale migration into Britain during the Middle to Late Bronze Age". Nature. 601 (7894): 588–594. Bibcode:2022Natur.601..588P. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04287-4. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 8889665. PMID 34937049.

- ^ Armada, Xosé-Lois (August 2020). Massive metalwork deposition in Atlantic Europe during the Late Bronze Age – Iron Age transition: towards a refined chronology?. hdl:10261/237815. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Nigrán (16 February 2019). "El castro de Chandebrito duró mil años". Faro de Vigo. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Redacción (23 December 2021). "Penas do Castelo, un dos castros máis antigos de Galicia". GCiencia. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Nión-Álvarez, Samuel (2016). "Punta de Muros y su excepcionalidad en el contexto del Hierro I en el Noroeste peninsular". IX Jornadas de Jóvenes en Investigación Arqueológica. Santander. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Cano Pan, Juan A. (2010). "El yacimiento de Punta de Muros". Anuario Brigantino. 33: 33–63.

- ^ Parcero-Oubiña, César; Armada, Xosé-Lois; Nión, Samuel; González Insua, Félix (9 September 2019). "All together now (or not). Change, resistance and resilience in the NW Iberian Peninsula in the Bronze Age-Iron Age transition". In Brais X. Currás; Inés Sastre (eds.). Alternative Iron Ages: Social Theory from Archaeological Analysis. Taylor & Francis. doi:10.4324/9781351012119. hdl:10261/208907. ISBN 9781351012119. S2CID 240654014.

- ^ Raso, Iciar Moreno (2014). "Longhouses del Bronce Final-Hierro I en la Península Ibérica". Arqueología y Territorio (11): 25–37. ISSN 1698-5664. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Fokkens, H.; Bourgeois, J.; Bourgeois, I.; Charette, B. (2003). "The longhouse as a central element in Bronze Age daily life". S2CID 162779452.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ García Quintela, Marco V. (14 July 2016). "Sobre las saunas de la Edad del Hierro en la Península ibérica: novedades, tipologías e interpretaciones". Complutum. 27 (1): 109–130. doi:10.5209/CMPL.53219. ISSN 1988-2327. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Armada, Xosé-Lois; García Vuelta, Óscar (2006). "Symbolic Forms from the Iron Age in the North-West of the Iberian Peninsula: Sacrificial Bronzes and their Problems". In Marco Virgilio García Quintela (ed.). Anthropology of the Indo-European world and material culture. Proceedings of the 5th International Colloquium of Anthropology of the Indo-European World and Comparative Mythology. Maior. Budapest: Archaeolingua. pp. 163–178. hdl:10261/34316. ISBN 978-963-8046-72-7. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Prieto Molina, Susana (1996). "Los torques castreños del noroeste de la Península Ibérica". Complutum (7): 195–224. ISSN 1131-6993. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Mederos Martin, Alfredo (20 December 2019). "Auga dos Cebros (Pontevedra, Galicia): Un barco del Bronce Final II en la fachada atlántica de la Peníncula Ibérica (1325-1050 a. C.)". SAGVNTVM. Papeles del Laboratorio de Arqueología de Valencia. 51: 23. doi:10.7203/SAGVNTVM.51.11476 (inactive 1 July 2025). hdl:10486/691528. S2CID 214517194.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ González Ruibal, Alfredo; Rodríguez Martínez, Rafael; Ayán Vila, Xurxo (2010). "Buscando a los púnicos en el noroeste". Mainake. XXXII: 24. ISSN 0212-078X.

- ^ Meunier, Emmanuelle (1 December 2019). "El estaño del Noroeste ibérico desde la Edad del Bronce hasta la época romana. Por una primera síntesis". La ruta de las Estrímnides. Universidad de Alcalá, Servicio de Publicaciones. pp. 279–320. ISBN 978-84-17729-31-8.

- ^ Alonso Romero, Fernando (1995). Las embarcaciones y navegaciones en el mundo celta: de la Edad Antigua a la Alta Edad Media. Guerra, exploraciones y navegación : del mundo antiguo a la edad moderna : curso de verano (U.I.M.P., Universidade de A Coruña) : Ferrol, 18 a 21 de julio de 1994. Servizo de Publicacións. pp. 111–146. ISBN 978-84-88301-13-0. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Romero Masiá, Ana María; Pose Mesura, Xosé Manuel (1988). Galicia nos textos clásicos (in Galician). Galiza: Edicións do Padroado do Museu Arqueolóxico Provincial, Concello de A Coruña. pp. 55, 71, 86. ISBN 84-505-7380-7. OCLC 28499276.

- ^ "The dating of the Lomba do Mouro site makes it the largest and oldest Roman camp in Galicia and northern Portugal – The Roman Army in the NW of Hispania". 2 June 2021. Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Rodríguez Corral, Javier (2009). A Galicia castrexa (in Galician). Santiago de Compostela: Lóstrego. p. 214. ISBN 978-84-936613-3-5. OCLC 758056842.

- ^ Álvarez González, Yolanda; López González, Luis; Fernández-Götz, Manuel; García Quintela, Marco V. (2017). "El oppidum de San Cibrán de Las y el papel de la religión en los procesos de centralización en la Edad del Hierro". Cuadernos de Prehistoria y Arqueología. 43. doi:10.15366/cupauam2017.43.008. hdl:10347/24547. ISSN 0211-1608. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ culturagalega.org (7 March 2024). "Localizan no castro de Elviña indicios dunha destrución intencional". culturagalega.org. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ Romero Masiá, Ana; Pose Mesura, Xosé Manuel (1988). Galicia nos textos clásicos (in Galician). Galiza: Edicións do Padroado do Museu Arqueolóxico Provincial, Concello de A Coruña. pp. 95, 146. ISBN 84-505-7380-7. OCLC 28499276.

- ^ Fonte, João; Costa-García, Jose Manuel; Gago, Manuel (20 September 2021). "O Penedo dos Lobos: Roman military activity in the uplands of the Galician Massif (Northwest Iberia)". Journal of Conflict Archaeology. 17: 5–29. doi:10.1080/15740773.2021.1980757. hdl:10366/148231. ISSN 1574-0773. S2CID 240599598.

- ^ Smith, R. R. R. (1988). "Simulacra Gentium: the Ethne from the Sebasteion at Aphrodisias". Journal of Roman Studies. 78: 50–77. doi:10.2307/301450. ISSN 0075-4358. JSTOR 301450. S2CID 162542146. Archived from the original on 22 November 2023. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ culturagalega.org (11 December 2017). "Un arco de triunfo en Francia pode gardar a primeira representación dun guerreiro galaico vencido". culturagalega.org. Archived from the original on 22 November 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2022.