Gasoline Alley (comic strip)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

| Gasoline Alley | |

|---|---|

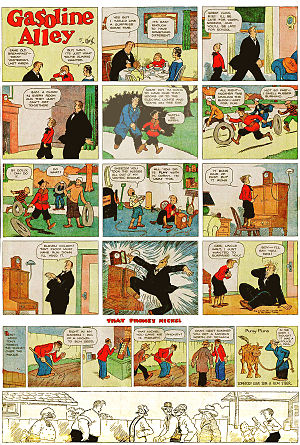

Frank King's Gasoline Alley and That Phoney Nickel (March 12, 1933) | |

| Author(s) | Frank King (1883–1969) Bill Perry (Sunday strips only, 1951–1975) Dick Moores (1956–1986) Jim Scancarelli (1986–present) |

| Current status/schedule | In syndication |

| Launch date | November 24, 1918 |

| Syndicate(s) | Tribune Content Agency[1] |

| Genre(s) | Humor, gag-a-day |

Gasoline Alley is a comic strip created by Frank King and distributed by Tribune Content Agency. It centers on the lives of patriarch Walt Wallet, his family, and residents in the town of Gasoline Alley, with storylines reflecting traditional American values.[2]

The strip debuted on November 24, 1918; as of 2024[update], it is the longest-running current strip in the United States, and the second-longest running strip of all time in the United States, after The Katzenjammer Kids (which ran for 109 years, 1897–2006). Gasoline Alley has received critical accolades for its influential innovations.[3] In addition to new color and page design concepts, King introduced real-time continuity to comic strips by depicting his characters aging over generations.[4]

Early years

[edit]

The strip originated on the Chicago Tribune's black-and-white Sunday page, The Rectangle, where staff artists contributed one-shot panels, continuing plots or themes. One corner of The Rectangle introduced King's Gasoline Alley, where characters Walt, Doc, Avery, and Bill held weekly conversations about automobiles. This panel slowly gained recognition, and the daily comic strip began August 24, 1919, in the New York Daily News.[5]

Some of the early characters were based on people Frank King knew. Skeezix was based on his son Robert Drew King. Walt was based on "jolly" overweight bachelor and Western Union traffic engineer Walter W. Drew, who had "a wisp of unruly hair". Bill and Amy were based on locomotive engineer William D. Gannon and his wife Gertrude.[6] Doc was based on Dr. Hughie Johnson.[7]

Skeezix arrives

[edit]The early years were dominated by the character Walt Wallet. Tribune editor Joseph Patterson wanted to attract women to the strip by introducing a baby, but Walt was not married. That obstacle was avoided when Walt found a baby on his doorstep, as described by comics historian Don Markstein:

After a couple of years, the Tribune's editor, Captain Joseph Patterson, whose influence would later have profound effects on such strips as Terry and the Pirates and Little Orphan Annie, decided the strip should have something to appeal to women, as well, and suggested King add a baby. Only problem was the main character, Walt Wallet, was a confirmed bachelor. On February 14, 1921, Walt found the necessary baby abandoned on his doorstep. That was the day Gasoline Alley entered history as the first comic strip in which the characters aged normally. (Hairbreadth Harry had grown up in his strip, but stopped aging in his early 20s.) The baby, named Skeezix (cowboy slang for a motherless calf), grew up, fought in World War II, and is now a retired grandfather. Walt married after all, and had more children, who had children of their own. More characters entered the storyline on the periphery and some grew to occupy center stage.[4]

Skeezix called his adoptive father Uncle Walt. Unlike most comic strip children (like the Katzenjammer Kids or Little Orphan Annie), he did not remain a baby or even a little boy for long. He grew up to manhood, the first occasion where real time was shown continually elapsing in a major comic strip over generations. By the time the United States entered World War II, Skeezix was an adult, courting Nina Clock and enlisting in the armed forces in June 1942. He later married Nina and had children. In the late 1960s, he faced a typical midlife crisis. Walt Wallet himself married Phyllis Blossom on June 24, 1926, and had other children, who grew up and had kids of their own. During the 1970s and 1980s, under Dick Moores' authorship, the characters stopped aging. When Jim Scancarelli took over, natural aging was restored.[4]

Sunday strips

[edit]The Sunday strip was launched October 24, 1920. The 1930s Sunday pages did not always employ traditional gags, but often offered a gentle view of nature, imaginary daydreaming with expressive art, or naturalistic views of small-town life. Reviewing Peter Maresca and Chris Ware's Sundays with Walt and Skeezix (Sunday Press Books, 2007), comics critic Steve Duin quoted writer Jeet Heer:

Unlike the daily strips, which traced narratives that went on for many months, the Sunday pages almost always worked as discrete units," Heer writes. "Whereas the dailies allowed events to unfold, Sunday was the day to savor experiences and ruminate on life. It is in his Sunday pages that we find King showing his visual storytelling skills at their most developed: with sequences beautifully testifying to his love of nature, his feeling for artistic form, and his deeply felt response to life.[8]

The Sunday pages included several toppers over the course of the run: That Phoney Nickel (Dec 14, 1930 – Sept 17, 1933), Puny Puns (Feb 5 – Sept 17, 1933), Corky (Aug 18, 1935 – 1945), and Little Brother Hugo aka Wilmer's Little Brother Hugo (January 30, 1944 – 1973).[9]

21st century

[edit]The strip is still published in newspapers in the 21st century. Walt Wallet is now well over a century old (124, as of February 2024[10]), while Skeezix has become a centenarian. Walt's wife Phyllis, age an estimated 105, died in the April 26, 2004, strip; Walt was left a widower after nearly eight decades of marriage. Walt Wallet appeared as a guest at Blondie and Dagwood's anniversary party, and on Gasoline Alley's 90th anniversary, Blondie, Beetle Bailey, Dennis the Menace, and Snuffy Smith each acknowledged the Gasoline Alley anniversary in their dialogue. Snuffy Smith presented a character crossover with Walt in the doorway of Snuffy's house where he was being welcomed and invited in by Snuffy.[11] In May 2013 at the cartoon retirement home, Walt is at a dinner when Maggie's (of Bringing Up Father) pearl brooch is stolen; Fearless Fosdick is his usual incompetent self trying to catch the thief; cameos include such "retired" comics characters as Lil' Abner; Smokey Stover and Pogo and Albert. Even the active cartoon character Rex Morgan, M.D., appears.

Characters

[edit]

First-generation characters

[edit]- Walt Wallet

- Full name Walter Weatherby Wallet. Patriarch of the family and veteran of World War I.[12] For many years, he ran a successful furniture company, Wicker and Wallet. He has been retired for years.

- Phyllis Corkleigh Blossom Wallet

- Walt's wife. Phyllis was widowed before marrying Walt; Corkleigh was her maiden name before Blossom was her married name. Phyllis and Walt married June 24, 1926.[12] She died April 26, 2004.[12]

- Avery

- Walt's cranky neighbor, who drove an old car that started with a crank long after everyone else had bought a car with a starter. He died "off-stage."

- Bill

- He also died "off-stage".

- Doc

- He retired with a young woman on his arm, going off to a well-deserved retirement community. He died "off-stage".

- Uriah Pert

- A rich and miserly man. He was long the villain of many stories. Since his death his reputation has been rehabilitated a little bit, and shown to have a better character than his nephew, Senator Bobble.

Timeless characters

[edit]These characters break the strip's rule about aging with the calendar.

- Joel

- Trashman. He drives a wagon drawn by a mule named Betsy. His full name Joseph L. Smith is mentioned June 4, 1965.

- Rufus

- A "good-for-not-much". He frequently accompanies Joel. He always has "kitty" hanging from the crook of his arm. He lives in a shack.

- Magnus

- Rufus' no-good brother. He is usually in jail.

- Melba Rose

- The forever mayor of the city. The strip on June 15, 2022, shows her as the current mayor.

Second-generation characters

[edit]- Allison "Skeezix" Wallet

- After Walt, the central character of the strip. He was left on Walt's doorstep February 14, 1921. He was born February 9, 1921. He married Nina Clock on June 28, 1944. For years he ran the Gasoline Alley Garage. Now he sometimes minds it when Clovia and Slim are away.

- Nina Clock Wallet

- Skeezix's wife.

- Sarge (Sgt. Bloney)

- Fought in WWII in Africa, Italy, and Yugoslavia alongside Skeezix and later worked as a handyman and mechanic for him.

- Hack

- WWII veteran who worked for Skeezix as a mechanic. His automotive repair skills were the reason the Wallet & Bobble Co. branched into automotive repairs and built the Gasoline Alley Garage.

- Corkleigh "Corky" Wallet

- Walt and Phyllis' son, born May 2, 1928, named after Phyllis's maiden name. He married Hope Hassel on October 1, 1949. He runs a diner in a standalone building.

- Hope Hassel Wallet

- Corky's wife.

- Judy Wallet Grubb

- Left in Walt's car February 28, 1935. She married Gideon Grubb on May 4, 1961.

- Senator Wilmer Bobble

- Pert's nephew. Originally an office coworker with Skeezix at Wumple & Co. in Detropolis. He also occasionally met Skeezix as a fellow soldier in Africa in WWII. After the war he partnered with Skeezix to form the Wallet and Bobble Co. This was originally a handyman and general repair business, but soon branched into automotive repairs and started the Gasoline Alley Garage. Went on to become an example of a self-serving politician. When seen he is disliked and is often the villain of the current story.

Principal characters of subsequent generations

[edit]- Clovia Wallet Skinner

- Third generation. Skeezix and Nina's daughter. Born May 15, 1949. Married Slim Skinner. She runs the business end of the Gasoline Alley Garage.

- Slim Skinner

- Third generation. Married Clovia. Overweight and seems a slacker. He is principal, and perhaps only, mechanic at the Garage. Sometimes seen are Slim's greedy, manipulative card-playing mother Lil, and cousin Chubby. Clovia considers both Lil and Chubby to be no good (particularly Lil, who frequently causes trouble and is quick to blame others for her wrongdoing).

- Thomas Walter "Chipper" Wallet

- Third generation. Skeezix and Nina's son. Born April 1, 1945. He went to college, then joined the Navy and served in the Vietnam War as a medic. After leaving the Navy he became a Physician Assistant.

- Phylip Figg "Nubbin" Wallet

- Third generation. Corky and Hope's first child. Born January 1, 1954.

- Adam Wallet

- Third generation. Corky's son. Born April 21, 1960. He came back from Peace Corps work in the South Pacific, with his new wife, and took over the old Clock farm in the country.

- Eve Wallet

- Third generation. Corky's daughter, Adam's twin sister. Born April 21, 1960. Apparently something of a black sheep of the family, she briefly moved into Walt's house after Phyllis' death, ostensibly to act as his caregiver. She invited a large number of people into the house, police were called, and she was last seen in jail.[13]

- Teeka Tok Wallet

- Third generation. A native of a South Pacific island. Married Adam while he was working there. They later had a daughter, Ada Clock, born on August 8, 1988, and adopted a girl named Amanda Lynn.

- Rover Bump -> Skinner

- Fourth generation. A neglected child taken in and adopted by Clovia and Slim.

- Gretchen Skinner

- Fourth generation, born April 13, 1978. Daughter of Clovia and Slim, and a childhood companion of Rover. As a child, her eyes were drawn without pupils.

- Hoogy Boogle

- Fourth generation. Another neglected child who sometimes stayed in Clovia and Slim's household. Married Rover.

- Boog Skinner

- Fifth generation. The son of Rover and Hoogy born offscreen in the September 8, 2004, strip.[14]

- Aubee Rose Skinner

- Fifth generation. Daughter of Rover and Hoogy. Delivered by Chipper Wallet in the September 10, 2016, strip.[14]

Writer-artist chronology

[edit]Daily:

- Frank King: Nov 24, 1918 – Dec 31, 1969

- Dick Moores: 1956 – Aug 23, 1986

- Jim Scancarelli: Aug 25, 1986 – present[15]

Sunday:

- Frank King: Oct 24, 1920 – April 22, 1951

- Bill Perry: April 29, 1951 – Aug 17, 1975

- Dick Moores: Aug 25, 1975 – Aug 24, 1986

- Bob Zschiesche: 1976–1979

- Jim Scancarelli: ghosting 1979–1986, credited Aug 25, 1986 – present[15]

King was succeeded by his former assistants, with Bill Perry taking responsibility for Sunday strips in 1951 and Dick Moores, first hired in 1956, becoming sole writer and artist for the daily strip in 1959. When Perry retired in 1975, Moores took over the Sunday strips, as well, combining the daily and Sunday stories into one continuity starting September 28, 1975. Moores died in 1986, and since then, Gasoline Alley has been written and drawn by Scancarelli, former assistant to Moores. Scancarelli returned to done-in-one separate situations for the Sunday strip.[11]

Awards

[edit]The strip and King were recognized with the National Cartoonists Society's Humor Strip Award in 1957, 1973, 1980, 1981, 1982, and 1985. King received the 1958 Society's Reuben Award, and Moores received it in 1974. Scancarelli received the Society's Story Comic Strip Award in 1988. The strip received an NCS plaque for the year's best story strip in 1981, 1982 and 1983.[16]

Reprint collections

[edit]Examples of the full page Sunday strip were printed in The Comic Strip Century (1995, reissued in 2004 as 100 Years of Comic Strips), edited by Bill Blackbeard, Dale Crain and James Vance. Moores' dailies and Sundays have appeared in Comics Revue monthly, as have the first Scancarelli strips. In 1995, the strip was one of 20 included in the Comic Strip Classics series of commemorative US postage stamps.

Frank King's Gasoline Alley Nostalgia Journal

[edit]In 2003, Spec Productions began a series of softcover collections, Frank King's Gasoline Alley Nostalgia Journal, reprinting the strip from the first Rectangle panel (November 24, 1918). To date, four volumes have appeared:

- Volume 1, November 24, 1918, to September 22, 1919

- Volume 2, September 23, 1919, to March 2, 1920

- Volume 3, March 3, 1920, to July 25, 1920

- Volume 4, July 26, 1920, to December 31, 1920

Walt and Skeezix

[edit]In 2005, the first of a series of reprint books, Walt and Skeezix, was published by Drawn & Quarterly, edited by Chris Ware and included contributions by Jeet Heer. The first volume covers 1921–22, beginning several weeks before baby Skeezix appears. These reprint only the daily strips, with Sundays slated to appear in another series:[17]

Sunday Press

[edit]In 2007, Sunday Press Books published Sundays with Walt and Skeezix, which collects early Sunday strips in the original size and color.

Dark Horse

[edit]In 2014, Dark Horse Comics published Gasoline Alley: The Complete Sundays Volume 1 1920–1922 and Gasoline Alley: The Complete Sundays Volume 2 1923–1925 in hardback.

Dick Moores

[edit]Moores' work on the strip was published in three different collections, all currently out of print, as well as being serialized in Comics Revue magazine:

- Gasoline Alley: Comic Art as Social Comment: Changing Life in America Over More Than Half a Century as Seen Through the Eyes of a Unique 'First Family', Avon/Flare, 1976. Introduction by Nat Hentoff, history of the strip with 1970s continuities. ISBN 0-380-00761-4

- The Smoke from Gasoline Alley, Sheed and Ward, 1976. ISBN 0-8362-0670-3

- Rover from Gasoline Alley, Blackthorne, 1985. Collects the strips introducing Slim and Clovia's adopted son Rover. ISBN 0-932629-00-8

On October 9, 2012, IDW Publishing's imprint The Library of American Comics published a hardback collection titled Gasoline Alley, Volume 1, collecting several years of the daily strip by Frank King and Dick Moores.[18]

Radio

[edit]Several radio adaptations were made. Uncle Walt and Skeezix in 1931 starred Bill Idelson as Skeezix with Jean Gillespie as Nina Clock. Jimmy McCallion was Skeezix in the series that ran on NBC from February 17 to April 11, 1941, continuing on the Blue Network from April 28 to May 9 of that same year. The 15-minute series aired weekdays at 5:30 pm. Along with Nina (Janice Gilbert), the characters included Skeezix's boss Wumple (Cliff Soubier) and Ling Wee (Junius Matthews), a waiter in a Chinese restaurant. Charles Schenck directed the scripts by Kane Campbell.

The syndicated series of 1948–49 featured a cast of Bill Lipton, Mason Adams, and Robert Dryden. Sponsored by Autolite, the program used opening theme music by the Polka Dots, a harmonica group. The 15-minute episodes focused on Skeezix running a gas station and garage, the Wallet and Bobble Garage, with his partner, Wilmer Bobble. In New York, this series aired on WOR from July 16, 1948, to January 7, 1949.[19]

Films

[edit]Gasoline Alley was adapted into two feature films, Gasoline Alley (1951) and Corky of Gasoline Alley (1951). The films starred Jimmy Lydon as Skeezix, known at that time for Life with Father (1947) and his earlier character of Henry Aldrich.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ "Gasoline Alley comics by Jim Scancarelli". Tribune Content Agency. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ Baldwin, Jay E. (2014). "Gasoline Alley". In Booker, M. Keith (ed.). Comis Through Time: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas. ABC-CLIO. p. 597. ISBN 978-0313397516. Retrieved April 12, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ "At 75, Blondie's more modern now, but still ageless". Christian Science Monitor. 31 August 2005. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Gasoline Alley at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on August 1, 2016.

- ^ "On The Road With Gasoline Alley". Stevestiles.com. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Chase, Al (October 25, 1924). "This Tells Who 'Gasoline Alley' Folk Really Are". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ King, Frank (May 22, 1955). "My Home Town, Where Gasoline Alley and I Grew Up". Chicago Tribune Magazine. p. 29.

- ^ Oregonian/OregonLive, Steve Duin | For The (5 August 2007). "Sundays with Walt and Skeezix". Oregonlive.com. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Holtz, Allan (2012). American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. pp. 112, 237, 324, 380. ISBN 9780472117567.

- ^ "Gasoline Alley strip". Gocomics.com. 2014-01-05. Retrieved 2014-03-02.

- ^ a b "Gasoline Alley turns 90 today". The Daily Cartoonist. 24 November 2008. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ a b c King entry, Lambiek's Comiclopedia. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- ^ Scancarelli, Jim (14 August 2004). "Gasoline Alley by Jim Scancarelli for August 14, 2004 | GoComics.com". GoComics.com. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Gasoline Alley by Jim Scancarelli for Sep 9, 2004 | GoComics.com". GoComics. September 9, 2004. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ a b Holtz, Allan (2012). American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780472117567.

- ^ "NCS Awards". Archived from the original on 6 January 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Schwartz, Ben (14 January 2007). "See You in the (Restored, Reprinted) Funny Papers". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Gasoline Alley, Volume 1, Frank King and Dick Moores, ISBN 978-1613774403

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- ^ "Corky of Gasoline Alley". IMDb.com. 17 September 1951. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

KSF

KSF