Gavin McInnes

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 32 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 32 min

Gavin McInnes | |

|---|---|

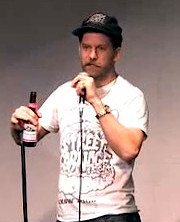

McInnes hosting The Gavin McInnes Show in 2015 | |

| Born | Gavin Miles McInnes 17 July 1970 Hitchin, Hertfordshire, England |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Education | Carleton University (BA) |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | |

| Movement | |

| Spouse |

Emily Jendrisak (m. 2005) |

| Children | 3 |

| Website | Compound Censored[1] |

Gavin Miles McInnes (/məˈkɪnɪs/; born 17 July 1970) is a Canadian writer, podcaster, far-right commentator and founder of the Proud Boys. He is the host of Get Off My Lawn with Gavin McInnes on his website, Compound Censored.[1][2] He co-founded Vice magazine in 1996 and relocated to the United States in 2001. In 2016 he founded the Proud Boys, an American far-right militant organization[3] which was designated a terrorist group in Canada[4][5] and New Zealand after he left the group.[6] McInnes has been described as promoting violence against political opponents[7] but has argued that he has only supported political violence in self-defense and that he is not far-right or a supporter of fascism, instead identifying as "a fiscal conservative and libertarian."[8]

Born to Scottish parents in Hertfordshire, England, McInnes emigrated to Canada as a child. He graduated from Carleton University in Ottawa before moving to Montreal and co-founding Vice with Suroosh Alvi and Shane Smith.[9] He relocated with Vice Media to New York City in 2001.[10][11] During his time at Vice, McInnes was called a leading figure in the New York hipster subculture.[12] He holds both Canadian and British citizenship and lives in Larchmont, New York.[9]

In 2018, McInnes was fired from Blaze Media[13] and was banned from Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram for violating terms of use related to promoting violent extremist groups and hate speech.[14][15] In June 2020, McInnes's account was suspended from YouTube for violating YouTube's policies concerning hate speech by posting content that was "glorifying [and] inciting violence against another person or group of people."[16]

Early life

[edit]Gavin Miles McInnes[17] was born on 17 July 1970[18] in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, England,[19] the son of Scottish parents James McInnes, who later became the Vice-President of Operations at Gallium Visual Systems Inc. – a Canadian defence company – and Loraine McInnes, a retired business teacher.[20] His family migrated to Canada when McInnes was four,[citation needed] settling in Ottawa, Ontario.[21] He attended Ottawa's Earl of March Secondary School.[22] As a teen, McInnes played in an Ottawa punk band called Anal Chinook.[23] He graduated from Carleton University.[20]

Career

[edit]Vice Media (1994–2007)

[edit]McInnes joined Voice magazine (later Voice of Montreal) in 1994 as assistant editor and cartoonist, under editor Suroosh Alvi. The magazine was established by Interimages Communications under a job creation program of the Quebec government to allow social welfare recipients to gain work experience. It focused on Montreal's alternative cultural scene, including music, art, trends and drug culture, to compete with the already established Montreal Mirror.[24][25][26][27] Alvi, McInnes and Shane Smith bought the magazine from the publisher and changed the magazine's name to Vice in 1996.[28][29]

Richard Szalwinski, a Canadian software millionaire, acquired the magazine and relocated the operation to New York City in the late 1990s.[30][31]

During McInnes's tenure he was described as the "godfather" of hipsterdom by WNBC[32] and as "one of hipsterdom's primary architects" by AdBusters.[33] He occasionally contributed articles to Vice, including "The VICE Guide to Happiness"[34] and "The VICE Guide to Picking Up Chicks",[35] and co-authored two Vice books: The Vice Guide to Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll,[36] and Vice Dos and Don'ts: 10 Years of VICE Magazine's Street Fashion Critiques.[37]

In an interview in the New York Press in 2002, McInnes said that he was pleased that most Williamsburg hipsters were white.[38][39] McInnes later wrote in a letter to Gawker that the interview was done as a prank intended to ridicule "baby boomer media like The Times".[40] After he became the focus of a letter-writing campaign by a black reader, Vice apologized for McInnes's comments.[39] McInnes was featured in a 2003 New York Times article about Vice magazine; McInnes' political views were described by the Times as "closer to a white supremacist's."[39]

In 2006, he was featured in The Vice Guide to Travel with actor and comedian David Cross in China.[41] He left Vice in 2008 due to what he described as "creative differences".[10] In a 2013 interview with The New Yorker, McInnes said his split with Vice was about the increasing influence of corporate advertising on Vice's content, stating that "Marketing and editorial being enemies had been the business plan".[42]

After Vice (2008–2018)

[edit]

After leaving Vice in 2008, McInnes became increasingly known for far-right political views.[8]

In 2008, McInnes created the website StreetCarnage.com. He also co-founded an advertising agency called Rooster where he served as creative director.[43]

McInnes was featured in season 3 of the Canadian reality TV show Kenny vs. Spenny, as a judge in the "Who is Cooler?" episode. In 2010, McInnes was approached by Adult Swim and asked to play the part of Mick, an anthropomorphic Scottish soccer ball, in the short-lived Aqua Teen Hunger Force spin-off Soul Quest Overdrive.[44] After losing a 2010 pilot contest to Cheyenne Cinnamon and the Fantabulous Unicorn of Sugar Town Candy Fudge, six episodes of Soul Quest Overdrive were ordered, with four airing in Adult Swim's 4 AM DVR Theater block on 25 May 2011 before quickly being cancelled. McInnes jokingly blamed the show's cancellation on the other cast members (Kristen Schaal, David Cross, and H. Jon Benjamin) not being "as funny" as him.[45]

McInnes wrote a column for Taki's Magazine, beginning around 2011, that made casual use of racial and anti-gay slurs, as described by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC).[46]

McInnes has also written columns for American Renaissance, a white supremacist magazine.[47][48]

In 2012, McInnes wrote a memoir book called How to Piss in Public.[49] In 2013 he directed The Brotherhood of the Traveling Rants, a documentary on his tour as an occasional standup comedian.[50] For the film, he faked a serious car accident. Also that year, McInnes starred in the independent film How to Be a Man, which premiered at Sundance Next Weekend.[51] He has also played supporting roles in other films including Soul Quest Overdrive (2010), Creative Control (2015) and One More Time (2015).

In August 2014, McInnes was asked to take an indefinite leave of absence as chief creative officer of Rooster, following online publication at Thought Catalog of an essay about transphobia titled "Transphobia is Perfectly Natural"[52] that sparked a call to boycott the company. In response, Rooster issued a statement, saying in part: "We are extremely disappointed with his actions and have asked that he take a leave of absence while we determine the most appropriate course of action."[53]

In June 2015, broadcaster Anthony Cumia announced that McInnes would be hosting a show on his network, therefore retiring the Free Speech podcast that he had started in March. The Gavin McInnes Show premiered on Compound Media on 15 June. McInnes is a former contributor to Canadian far-right portal The Rebel Media[54] and a regular on conspiracy theorist media platform Infowars' The Alex Jones Show, and Fox News' Red Eye, The Greg Gutfeld Show, and The Sean Hannity Show.

In 2016, he founded the Proud Boys, a neo-fascist,[55][56][57] men's rights and male-only organisation classified as a "general hate" organization by the SPLC.[58] He has rejected this classification, claiming that the group is "not an extremist group and [does] not have ties with white nationalists".[59]

McInnes left Rebel News in August 2017, declaring that he was going to be "a multi-media Howard Stern-meets-Tucker Carlson".[60] He later joined CRTV, an online television network launched by Conservative Review. The debut episode of his new show Get Off My Lawn aired on 22 September 2017.[61][62]

Events in 2018

[edit]On 10 August 2018, McInnes' Twitter account, as well as the account for the Proud Boys, was permanently suspended by Twitter due to their rules against violent extremist groups. The suspension was ahead of the first anniversary of the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the small Unite the Right 2 Washington protest in August 2018 in which the Proud Boys participated.[63][64][65]

On 12 October 2018, at the Metropolitan Republican Club, McInnes participated in a reenactment of the 1960 assassination of socialist politician Inejiro Asanuma by 17-year-old right-wing ultranationalist Otoya Yamaguchi during a televised debate. After the event, a contingent of Proud Boys were caught on tape beating a protester outside the venue,[66] after a leftist protester threw a plastic bottle at them.[67]

On 21 November 2018, shortly after news broke that the FBI had reportedly classified the Proud Boys as an extremist group with ties to white nationalists, McInnes said that his lawyers had advised him that quitting might help the nine members being prosecuted for the incidents in October and he said "this is 100% a legal gesture, and it is 100% about alleviating sentencing", and said it was a "'stepping down gesture', in quotation marks".[59][68] Two weeks later the Special Agent in Charge of the FBI's Oregon office said that it had not been their intent to label the entire group as "extremist",[69] only to characterize the possible threat from certain members of the group that way.[70]

Later that month, McInnes was planning on travelling to Australia for a speaking tour with Milo Yiannopoulos and Tommy Robinson (Stephen Yaxley-Lennon's pseudonym), but was informed by Australian immigration authorities that "he was judged to be of bad character" and would be denied a visa to enter the country. Issuing a visa to McInnes was opposed by an online campaign called "#BanGavin", which collected 81,000 signatures.[71][72]

On 3 December 2018, Conservative Review Television (CRTV), on which McInnes had hosted the Get Off My Lawn program, merged with BlazeTV, the television arm of Glenn Beck's TheBlaze, to become Blaze Media. McInnes was expected to host his program for the new company, whose co-president called McInnes "a comedian and provocateur, one of the many varied voices and viewpoints on Blaze Media platforms." Less than a week later, on 8 December, it was announced that McInnes was no longer associated with Blaze Media, with no details given as to why.[73][74]

Two days later, on 10 December, McInnes, who had previously been banned by Amazon, PayPal, Twitter, and Facebook, was banned from YouTube for "multiple third-party claims of copyright infringement."[75] Asked to comment about his firing and bannings, McInnes said that he had been victimized by "lies and propaganda", and that "there has been a concerted effort to de-platform me." In his e-mail to Huffington Post, McInnes stated that "Someone very powerful decided long ago that I shouldn't have a voice ... I'm finally out of platforms and unable to defend myself. ... We are no longer living in a free country."[76] McInnes also indicated some personal responsibility for the situation in an interview on the ABC News program Nightline, saying. "I'm not guilt free in this. There's culpability there. I shouldn't have said, you know, violence solves everything or something like that without making the context clear and I regret saying things like that." McInnes stopped short of apologizing or actually retracting his past statements, saying, "That ship has sailed."[77][78]

Larchmont lawn sign controversy

[edit]In reaction to the Proud Boys fight in October 2018, residents of the suburban Westchester community of Larchmont, where McInnes lives, began a "Hate Has No Home Here" campaign, which involved displaying that slogan on lawn signs around the community. One resident said "We stand together as a community, and violence and hate are not tolerated here." Several days after the signs began appearing, McInnes' wife sent emails to their neighbours saying that the media had misrepresented McInnes.[79]

Amy Siskind, an activist and writer who lives in nearby Mamaroneck, posted on Facebook that she was planning an anti-hate vigil. After a local newspaper ran a story about it, McInnes and his family appeared at Siskind's door without invitation or forewarning; she called the police.[79]

At the end of December, with the lawn sign campaign still ongoing, McInnes wrote a letter which was dropped off at the homes of his neighbours. In it, he asked them to take down their signs, and described himself as "a pro-gay, pro-Israel, virulently anti-racist libertarian," saying that there was nothing "hateful, racist, homophobic, anti-Semitic or intolerant" in "any of my expressions of my worldview," contrary to his past remarks, such as saying he was "becoming anti-Semitic" after a trip to Israel, or referring to transgender people as "gender niggers". McInnes said that the Proud Boys was a "drinking club [he] started several years ago as a joke". Despite the letter's formality, in a podcast on 4 January 2019, McInnes called the neighbours "assholes", described their behaviour as "cunty" and said "If you have that sign on your lawn, you're a fucking retard."[79]

One Larchmont resident said about him: "I don't care what Gavin says, I've done my research ... He incites violence. He spouts divisive, racist language. And while he may try to say he disowns his followers, he's a part of the problem. So when I read his letter, I was like, yeah, right, this is ridiculous."[80]

Several days after the letter was sent out, HuffPost reported that they had viewed evidence provided by some neighbours that McInnes' wife, Emily – who identifies as a liberal Democrat – had harassed and intimidated them, including with the threat of legal action. Her threats were such that several neighbours notified the police.[79]

Lawsuit against the SPLC

[edit]Although McInnes cut ties with the Proud Boys publicly in November 2018, stepping down as chairman,[59][68] in February 2019 he filed suit against the Southern Poverty Law Center over their designation of the Proud Boys as a "general hate" group. The defamation suit was filed in federal court in Alabama. In the papers filed, McInnes claimed that the hate group designation is false and motivated by fund-raising concerns, and that his career has been damaged by it. He claimed that SPLC contributed to his or the Proud Boys' being deplatformed by Twitter, PayPal, Mailchimp, and iTunes.[81][82]

The SPLC says on its website that "McInnes plays a duplicitous rhetorical game: rejecting white nationalism and, in particular, the term 'alt-right' while espousing some of its central tenets," and that the group's "rank-and-file [members] and leaders regularly spout white nationalist memes and maintain affiliations with known extremists. They are known for anti-Muslim and misogynistic rhetoric. Proud Boys have appeared alongside other hate groups at extremist gatherings like the 'Unite the Right' rally in Charlottesville."[58][82] In response to the suit, Richard Cohen, the president of SPLC, wrote "Gavin McInnes has a history of making inflammatory statements about Muslims, women, and the transgender community. The fact that he's upset with SPLC tells us that we're doing our job exposing hate and extremism."[82]

Compound Censored and other ventures (2019-present)

[edit]Censored.TV and Get Off My Lawn launch

[edit]In 2019, McInnes launched Censored.TV, an online video platform. The platform was originally named FreeSpeech.TV, but was changed to its current title for copyright purposes. The platform features McInnes' primary show, Get Off My Lawn (GOML). GOML is a pre-recorded, daily show which airs on weekdays with Thursdays as an exception, in which the show airs live under the alternative title Get Off My Lawn Live.[citation needed]

In May 2021, Milo Yiannopoulos wrote on Telegram that Censored.TV is "laying off all its staff" and lacked enough funding to sustain production of Yiannopoulous' show on the platform.[83] McInnes later dismissed these allegation whilst announcing the arrival of several new shows on his platform.[84][independent source needed]

On 27 August 2022, McInnes faked his own arrest during a live broadcast of Censored.TV. In the recording, McInnes appeared to look off past the camera, before saying ""We're shooting a show, can we do this another time?" adding "I didn't let you in." McInnes then walked off the set. It was widely speculated that McInnes had been arrested, until former McInnes-ally Owen Benjamin outed McInnes by posting text messages between the two of them. "Prank. Don't tell," McInnes wrote to Benjamin. Benjamin responded, "U gonna reveal its a prank? Cuz I have friends writing blogs about it." McInnes replied "Never," adding that he "never said" the FBI had raided his studio. After being outed by Benjamin, McInnes returned to the public on 6 September 2022.[85][86]

In December 2022, McInnes interviewed Kanye West and white nationalist Nick Fuentes. In the interview, McInnes claimed to be trying to save West from his own antisemitism; McInnes faulted not Jews but "liberal elites of all races", while West said Jews should forgive Adolf Hitler and predicted that antisemitism would be "awesome for a presidential campaign".[87][88][89]

Compound Censored

[edit]In June 2024, radio personality Anthony Cumia announced that his subscription-based platform, Compound Media, was closing down, and that he was to merge his network and The Anthony Cumia Show with McInnes' Censored.TV network.[90][91] The merger lead to the portmanteau renaming of Censored.TV to Compound Censored.[1]

New York trial of Proud Boys

[edit]Although McInnes was not a defendant in the August 2019 trial of members of the Proud Boys for their part in the violence that occurred after a meeting of the Metropolitan Republican Club in October 2018, prosecutors repeatedly invoked his name, his words and his views in their questioning of the defendants, after testimony by the defendants and other Proud Boys opened the door to that line of questioning. During closing arguments, a prosecutor said that "Gavin McInnes is not a harmless satirist. He is a hatemonger," while the defense said that McInnes was being "demonized."[92]

Views

[edit]McInnes describes himself as "a fiscal conservative and libertarian"[8] and part of the New Right, a term that he prefers rather than alt-right.[93] The New York Times has described McInnes as a far-right provocateur.[94] He has referred to himself as a "western chauvinist" and started a men's organization called Proud Boys who swear their allegiance to this cause.[95]

In November 2018 it was reported on the basis of an internal memo of the Clark County, Washington Sheriff's Office – based on an FBI briefing – that the Bureau classified the Proud Boys "an extremist group with ties to white nationalism".[96] Two weeks later, the Special Agent in Charge of the FBI's Oregon office denied that the FBI had made that designation about the entire group, ascribing it to a misunderstanding on the part of the Sheriff's Office.[69] The SAIC, Renn Cannon, said that their intent was simply to characterize the possible threat from certain members of the group, not to classify the entire group.[70] The Southern Poverty Law Center classifies them as a "general hate group".[58] McInnes has said his group is not a white nationalist group.[96]

In 2003, McInnes said, "I love being white and I think it's something to be very proud of. I don't want our culture diluted. We need to close the borders now and let everyone assimilate to a Western, white, English-speaking way of life."[97]

In a speech given at New York University in February 2017, after a clash between the Proud Boys and antifa protestors, McInnes said: "Violence doesn't feel good, justified violence feels great, and fighting solves everything. ... I want violence. I want punching in the face."[78] He says that he has only advocated for acting in self-defense.[98][99]

In 2024, the question of how McInnes's views had evolved away from the relatively progressive values of Vice was examined in the Canadian television documentary It's Not Funny Anymore: Vice to Proud Boys. [100]

Race and ethnicity

[edit]McInnes has been accused of racism[101] and of promoting white supremacist rhetoric.[94] He has used racial slurs against Susan Rice and Jada Pinkett Smith,[102][103] and more widely against Palestinians and Asians.[104][105] In September 2004, he told a reporter for the Chicago Reader at a party that he "wanted to fuck the shit out of [a young Asian lady] until she started talking." The reporter, Liz Armstrong, wrote: "He went on to posit that since Asians' eyes don't work so good in terms of facial expressions they have no choice but to emote with their mouths."[106]

McInnes has said that there is a "mass conformity that black people push on each other".[107] He is also listed as a contributor to the 2016 book Black Lies Matter which criticizes the Black Lives Matter movement. He said that New Jersey U.S. Senator Cory Booker, who is Black, is "kind of like Sambo."[108]

Religion

[edit]Judaism

[edit]In March 2017, a group of Rebel Media hosts, including McInnes, spent a week touring Israel. On the trip, McInnes made a non-Rebel video in which he defended Holocaust deniers, blamed Jews for the Treaty of Versailles, and said he was "becoming anti-Semitic".[109][110][111][112][113] The Times of Israel said he was "apparently drunk" in the video.[109][111] Israel National News called it a "faux rant" and "intentionally offensive".[113] He later said that his comments were taken out of context.[114] McInnes also produced a comedic video for Rebel called "Ten Things I Hate about Jews", later retitled "Ten Things I Hate About Israel".[112][110] After his statements were promoted by white supremacists (in contrast to other videos from the Rebel Media tour), McInnes publicly declined their support.[113] Upon McInnes' return to America, Rebel Media produced a video of McInnes in which he said, "I've got tons of Nazi friends. David Duke and all the Nazis totally think I rock... No offence, Nazis, I don't want to hurt your feelings, but I don't like you. I like Jews."[110][111] Rebel Media's owner, Ezra Levant, who is Jewish-Canadian, defended McInnes.[113] In a December 2022 interview for Censored.TV with Kanye West and the white nationalist Nick Fuentes, he said he was trying to save West from antisemitism and said that "every individual I meet starts off with a clean slate".[87][88][115]

Islam

[edit]McInnes is anti-Islam,[102][116] once stating that "Muslims are stupid... the only thing they really respect is violence and being tough."[117] He also has equated Islam with fascism, stating "Nazis are not a thing. Islam is a thing."[118] In April 2018, McInnes labelled a significant section of Muslims as both mentally ill and incestuous, claiming that "Muslims have a problem with inbreeding. They tend to marry their first cousins... and that is a major problem [in the U.S.] because when you have mentally damaged inbreds – which not all Muslims are, but a disproportionate number are – and you have a hate book called the Koran [sic]... you end up with a perfect recipe for mass murder."[58][119]

Gender

[edit]McInnes has described himself as "an Archie Bunker sexist",[94] and has said that "95 percent of women would be happier at home".[78] On the topic of female police officers, he said, "I understand [women] are good for domestics, but I don't understand why there are so many female police officers. They're not strong, they're like super fat police officers. It doesn't make any sense to me."[120]

In 2003, Vanessa Grigoriadis in The New York Times quoted McInnes saying, "'No means no' is puritanism. I think Steinem-era feminism did women a lot of injustices, but one of the worst ones was convincing all these indie norts that women don't want to be dominated."[97] McInnes has been accused of sexism by various media outlets including Chicago Sun-Times,[121] Independent Journal Review,[122] Salon,[123] Jezebel,[124] The Hollywood Reporter,[125] and Slate.[126] In October 2013, McInnes said during a panel interview that "people would be happier if women would stop pretending to be men" and that feminism "has made women less happy".[127] He said, "We've trivialized childbirth and being domestic so much that women are forced to pretend to be men. They're feigning this toughness, they're miserable."[128] A heated argument ensued with University of Miami School of Law professor Mary Anne Franks.[129]

White genocide

[edit]McInnes has espoused the white genocide conspiracy theory, saying that white women having abortions[130] and immigration is "leading to white genocide in the West".[131] In 2018, regarding South African farm attacks and land reform proposals, he said that black South Africans were not "trying to get their land back – they never had that land", instead stating there were "ethnic cleansing" efforts against white South Africans.[132]

Filmography

[edit]Film

[edit]- How to Be a Man (2013) – as Mark McCarthy

- Creative Control (2015) – as Scott

- One More Time (2015) – as Record Producer

- White Noise (2020) – as Himself

Television

[edit]- Kenny vs Spenny: "Who is Cooler" episode (2006) – as himself (guest judge)

- Soul Quest Overdrive (2010, 2011) – as Mick (voice)

- Vice Guide to Travel (2006) – as himself (host)

Personal life

[edit]In 2005, he married Manhattan-based publicist and consultant Emily Jendrisak, the daughter of Native American activist Christine Whiterabbit Jendrisak[20][133] who describes herself as a liberal Democrat.[78] About his wife's ethnicity and their children together, McInnes said, "I've made my views on Indians very clear. I like them. I actually like them so much, I made three."[134] They live in Larchmont, New York.[135]

In his 2020 documentary White Noise, and in a follow up article about alt-right activist Lauren Southern, Daniel Lombroso, a journalist for The Atlantic, reported that McInnes sexually propositioned Southern after an appearance on his show in June 2018. McInnes denied having done so.[136][137]

McInnes is a permanent resident of the United States.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Gavin McInnes, AiU, Jim Goad & More". Retrieved 9 March 2025.

- ^ "About CENSORED.TV". Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Founder of Proud Boys hate group shows up at hospital rally to support Trump". The Independent. 4 October 2020. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ Aiello, Rachel (3 February 2021). "Canada adds Proud Boys to terror list". CTVNews. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Government of Canada lists 13 new groups as terrorist entities and completes review of seven others". Government of Canada. 3 February 2021. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Kriner, Matthew; Lewis, Jon (July–August 2021). Cruickshank, Paul; Hummel, Kristina (eds.). "Pride & Prejudice: The Violent Evolution of the Proud Boys" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. 14 (6). West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center: 26–38. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^

- Noyes, Jenny (1 December 2018). "Far-right figure Gavin McInnes denied visa ahead of planned speaking tour". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- Wilson, Jason (5 February 2019). "Gavin McInnes is latest far-right figure to sue anti-hate watchdog". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- "Why are the Proud Boys so violent? Ask Gavin McInnes". Hatewatch. Southern Poverty Law Center. 18 October 2018. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

McInnes has a well-documented and long-running record of blatantly promoting violence and making threats. "We will kill you. That's the Proud Boys in a nutshell. We will kill you," he said on his "Compound Media" show in mid-2016. His followers often repeat his calls for violence and seemed especially emboldened this past summer as they participated in a number of large-scale "free speech" rallies across the country.

- Coaston, Jane (15 October 2018). "The Proud Boys, the bizarre far-right street fighters behind violence in New York, explained". Vox. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

It's that violence that the Proud Boys have become best known for, with the group even boasting of a "tactical defensive arm" known as the Fraternal Order of Alt-Knights (or "FOAK") reportedly with McInnes's backing. McInnes made a video praising the use of violence this June, saying, "What's the matter with fighting? Fighting solves everything. The war on fighting is the same as the war on masculinity."

- Aquilina, Kimberly M. (9 February 2017). "Gavin McInnes explains what a Proud Boy is and why porn and wanking are bad". www.metro.us. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

'People say if someone's fighting, go get a teacher. No, if someone's f-ing up your sister, put them in the hospital.'

- ^ a b c Feuer, Alan (16 October 2018). "Proud Boys Founder: How He Went From Brooklyn Hipster to Far-Right Provocateur". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Houpt, Sam (2017). "Vice co-founder Gavin McInnes's path to the far-right frontier". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ a b Alex Pareene (23 January 2008). "Co-Founder Gavin McInnes Finally Leaves 'Vice'". Gawker. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Benson, Richard (28 October 2017). "How Terry Richardson created porn 'chic' and moulded the look of an era". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Gavin McInnes: the godfather of vice". www.macleans.ca. 19 March 2012. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Roettgers, Janko (10 December 2018). "Proud Boys Founder Gavin McInnes Fired From Blaze Media, YouTube Account Disabled". Huffpost. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Roettgers, Janko (10 August 2018). "Twitter Shuts Down Accounts of Vice Co-Founder Gavin McInnes, Proud Boys Ahead of 'Unite the Right' Rally". Variety. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

Twitter suspended the accounts of Vice Magazine co-founder Gavin McInnes and his far-right Proud Boys group Friday afternoon...The accounts were shut down for violating the company's policies prohibiting violent extremist groups, Twitter said in a statement to BuzzFeed News

- ^ Sacks, Brianna (30 October 2018). "Facebook Has Banned The Proud Boys And Gavin McInnes From Its Platforms". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

The company confirmed Tuesday that it has begun shutting down a variety of accounts associated with the Proud Boys and its founder, Gavin McInnes, on both Facebook and Instagram, citing its 'policies against hate organizations and figures.'

- ^ Rozsa, Matthew (24 July 2020) "YouTube suspends account of Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes" Archived 25 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine Salon

- ^ "Vows: Emily Jendriasak and Gavin McInnes". Gawker. 28 September 2005. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (2013). "Zapped by Spaces Gun into a Shit Hole on Acid (1985)". The Death of Cool: From Teenage Rebellion to the Hangover of Adulthood. Simon and Schuster. p. 6. ISBN 9781451614183. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

In 1975, five years after a breathtakingly gorgeous baby Me was born

- ^ "11 arrested at protests over offensive comedian : News 2017 : Chortle : The UK Comedy Guide". Chortle. 3 February 2017. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ a b c "Emily Jendriasak and Gavin McInnes". Gawker.com. Gawker. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Gavin McInnes (2012). The Death of Cool. Simon and Schuster. p. 1. ISBN 9781451614183. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (2013). The Death of Cool: From Teenage Rebellion to the Hangover of Adulthood. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781451614183. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "Vice co-founder Gavin McInnes on Montreal junkies, Fox News and the death of cool". Nightlife.Ca. 14 March 2012. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Voice of Montreal Magazine V01 N01". Voice. Vol. 01, no. 1. Montreal: Interimages Communications. November 1994. p. 3. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- ^ "Ex Heroin Addict Turned Media Mogul, Outlook – BBC World Service". BBC. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ "How Shane Smith Built Vice Into a $2.5 Billion Empire". Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ "The 'Vice' Boys Are All Grown Up And Working For Viacom". Gawker. 19 November 2007. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012.

- ^ Jeff Bercovici (3 January 2012). "Vice's Shane Smith on What's Wrong With Canada, Facebook and Occupy Wall Street". Forbes. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ "On leaving Images Interculturelles" Alvi, Suroosh (2003). texts The Vice guide to sex and drugs and rock and roll. Warner Books. p. 5. ISBN 9780446692816.

- ^ Wiedeman, Reeves (10 June 2018). "Vice Media Was Built on a Bluff. What Happens When It Gets Called?". Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "Vice Media History". www.zippia.com. 27 August 2020. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ Mawuse Ziegbe (21 April 2010). "Vice" Founder Gavin McInnes on Split From Glossy: "It's Like a Divorce". NBC New York. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Douglas Haddow (29 July 2008). "Hipster: The Dead End of Western Civilization". Adbusters. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ "The VICE Guide To Happiness". Vice. December 2003. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ "The VICE Guide to Picking Up Chicks". Vice. December 2005. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ "The Vice Guide to Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll". Goodreads. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ Vice Dos and Don'ts. Goodreads. September 2004. ISBN 978-0-446-69282-3. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Vice Rising: Corporate Media Woos Magazine World's Punks". New York Press. 8 October 2002. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ a b c "The Edge of Hip: Vice, the Brand". The New York Times. 28 September 2003. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ Gavin McInnes. "Letter to Gawker from Gavin McInnes". Gawker.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Gavin McInnes (2 August 2007). "David Cross in China (part 1)". Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ Widdicombe, Lizzie (8 April 2013). "The Bad-Boy Brand". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ Braiker, Brian (20 June 2011). "Creating Ads For People Who Hate Ads". Adweek. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ "Adult Swim – Soul Quest Overdrive". Rooster. 27 May 2011. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ "Soul Quest Overdrive: Watch the Whole Series Here". StreetCarnage.com. 27 May 2011. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Martin, Nick R. (19 October 2018). "Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes has been using the same anti-gay slur hurled in the NYC attack for at least 15 years". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Williams, Phil (2 December 2024). "Inside the influential white-supremacist conference that calls Tennessee 'home away from home'". WTVF.

- ^ "Gavin McInnes". American Renaissance.

- ^ Barker, Paul (2 April 2012). "Gavin McInnes: An In-depth Interview With "The Godfather of Hipsterdom"". Thought Catalog. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ Grant, Drew (27 March 2012). "Gavin McInnes Wrecks Car, 'Loses' Best Friend in An Attempt to Win Back Dignity After Observer Punking (Video)". The Observer. London, England. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ von Zurmwall, Nate (11 August 2013). "Day 3: Gavin McInnes' Errant Life Tips in How To Be A Man; James Ponsoldt's Advice to Filmmakers". Sundance Film Festival. Archived from the original on 15 August 2013.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (12 August 2014). "Transphobia is Perfectly Natural". Thought Catalog. The Thought & Expression Company. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2014. Click "Continue" link at the very bottom of the warning page to view original article.

- ^ Monllos, Kristina (15 August 2014). "Rooster CCO Gavin McInnes Asked to Take Leave of Absence Following transphobic Thought Catalog essay, boycott". Adweek. Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ Brean, Joseph; Hauen, Jack; Smith, Marie-Danielle (18 August 2017). "Rebel Media meltdown: Faith Goldy fired as politicians, contributors distance themselves". National Post. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Weill, Kelly (29 January 2019) "How the Proud Boys Became Roger Stone’s Personal Army" Archived 29 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine The Daily Beast.

- ^ "Proud Boys Founder Gavin McInnes Wants Neighbors to Take Down Anti-Hate Yard Signs". lawandcrime.com. 5 January 2019. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ Mathias, Christopher (18 October 2018). "The Proud Boys, The GOP And 'The Fascist Creep'". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Proud Boys". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Jason (21 November 2018). "Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes quits 'extremist' far-right group". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ "The REAL reason I left The Rebel". therebel.media. 25 August 2017. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ "Get Off My Lawn Debut Episode Part 1". Crtv.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ "Get Off My Lawn Debut Episode Part 2". Crtv.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Mac, Ryan; Montgomery, Blake. "Twitter Suspends Proud Boys And Founder Gavin McInnes Accounts Ahead Of Unite The Right Rally". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ Roettgers, Janko (10 August 2018). "Twitter Shuts Down Accounts of Vice Co-Founder Gavin McInnes, Proud Boys Ahead of 'Unite the Right' Rally". Variety. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ Owen, Tess (13 August 2018). "Only about 2 dozen people showed up to the Unite the Right rally in D.C." Vice. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ "Gavin McInnes 'Personally I think the guy was looking to get beat up for optics'". Spectator USA. 13 October 2018. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ Feuer, Alan; Winston, Ali (19 October 2018). "Founder of Proud Boys Says He's Arranging Surrender of Men in Brawl". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

The police said the violence started after one of the leftist protesters threw a plastic bottle at the Proud Boys, who had with them members of far-right groups, like the 211 Bootboys and Batalion 49.

- ^ a b Prengel, Kate (21 November 2018). "Gavin McInnes Says He Is Quitting the Proud Boys [Video]". Heavy.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Maxine (4 December 2018) "Head of Oregon's FBI: Bureau doesn't designate Proud Boys as extremist group" Archived 6 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine The Oregonian

- ^ a b Barnes, Luke (7 December 2018) "FBI does U-turn on Proud Boys ‘extremist’ label" Archived 8 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine ThinkProgress

- ^ Wilson, Jason (30 November 2018) "Gavin McInnes: founder of far-right Proud Boys denied Australian visa – report" Archived 21 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian

- ^ Doran, Matthew (30 November 2018). "Far-right campaigner Gavin McInnes denied visa on character grounds". ABC News. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Bowden, John (8 December 2018) "BlazeTV breaks off relationship with founder of the Proud Boys" Archived 9 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine The Hill

- ^ Stelloh, Tim (9 December 2018) "'Proud Boys' founder Gavin McInnes out at Blaze Media" Archived 10 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine NBC News

- ^ Anapol Avery (10 December 2018) "YouTube bans Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes" Archived 10 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine The Hill

- ^ Miller, Hayley (10 December 2018) "Proud Boys Founder Gavin McInnes Fired From Blaze Media, YouTube Account Disabled" Archived 11 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine HuffPost

- ^ Levin, Jon (12 December 2018) "Gavin McInnes Says He 'Regrets' Past Remarks After Social Media Bans: 'I’m Not Guilt Free'" Archived 13 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine TheWrap

- ^ a b c d "Proud Boys founder denies inciting violence, responds to whether he feels responsible for group's behavior" (12 December 2018)Archived 13 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine ABC News

- ^ a b c d * Weill, Kelly (13 November 2018). "Gavin McInnes Whines His Fellow Rich Neighbors Don't Like Him". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Rom, Gabriel (29 October 2018). "Amy Siskind warns that far-right leader Gavin McInnes lives here". The Journal News. Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- Campbell, Andy (4 January 2019). "Proud Boys Founder Gavin McInnes Can Get Back To Antifa After He Battles His Neighbors". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Doughtery, Owen (4 January 2019). "Proud Boys founder asked neighbors to take down anti-hate signs: report". The Hill. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Sommer, Will (4 January 2019). "Gavin McInnes Writes Letters to Neighbors to Take Down Anti-Hate Signs". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Campbell, Andy (8 January 2019). "Gavin McInnes' Wife Threatens Neighbors Over 'Hate Has No Home Here' Signs". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Campbell, Andy (15 January 2019). "Gavin McInnes Is Losing The Battle To Win Over His Neighbors". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Associated Press (4 February 2019) "Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes sues Southern Poverty Law Center over hate group label" Archived 4 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine NBC News

- ^ a b c Kennedy, Merrit (5 February 2019) "Proud Boys Founder Files Defamation Lawsuit Against Southern Poverty Law Center" Archived 6 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine NPR

- ^ Petrizzo, Zachary (13 May 2021). "Proud Boy founder Gavin McInnes' far-right media site apparently collapsing". Salon. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (8 June 2021). "S03E118 "10 Things I Don't Get, Part 2"". Censored.TV. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ Griffing, Alex (6 September 2022). "Gavin McInnes Resurfaces on Vacation After Enraging Allies By Faking Arrest". Mediaite. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ Sommer, Will (31 August 2022). "Gavin McInnes Allies Believe Proud Boys Founder Faked Arrest". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ a b Young, Matt (6 December 2022). "Gavin McInnes Interviews Kanye in New Show to Talk Rapper 'Off the Ledge'". Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022 – via The Daily Beast.

- ^ a b Baio, Ariana (6 December 2022). "Kanye West hits new low claiming Jewish people should 'forgive Hitler today'". indy100. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (5 December 2022). "The Ye Interview". New York. New York, United States. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022 – via Censored.TV.

- ^ TACS 1775 (Streaming video). New York City, New York, United States: Compound Media. 25 June 2024.

- ^ "The Anthony Cumia Show | Censored.TV". Censored.TV. Retrieved 9 March 2025.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (14 August 2019) "Far-Right Proud Boys' Founder Called 'Hatemonger'" Archived 15 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times

- ^ Chung, Frank (21 August 2018). "Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes heading to Australia in November". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Feuer, Alan (16 October 2018). "Proud Boys Founder: How He Went From Brooklyn Hipster to Far-Right Provocateur". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ *Carter, Mike (1 May 2017). "Seattle police wary of May Day violence between pro- and anti-Trump groups". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 30 October 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- Long, Colleen (3 February 2017). "11 arrests at NYU protest over speech by 'Proud Boys' leader". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- Tasker, John Paul. "Head of Canada's Indigenous veterans group hopes Proud Boys don't lose their CAF jobs". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- McInnes, Gavin; Lewis, Jeffrey (14 April 2015). "Free Speech". Daily Motion. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ a b Wilson, Jason. "FBI now classifies far-right Proud Boys as 'extremist group', documents say". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ a b Grigoriadis, Vanessa (28 September 2003). "The Edge of Hip: Vice, the Brand". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (14 August 2019). "Far-Right Proud Boys' Founder Called 'Hatemonger'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ Marcotte, Amanda (16 October 2018). "Gavin McInnes and the Proud Boys: Defending themselves, or spoiling for a fight?". Salon. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ J. Kelly Nestruck, "Documentary about Proud Boys founder reminds Canadians of our role in stoking American extremism – and our denial about it". The Globe and Mail, October 22, 2024.

- ^ "Right-wing activist heading to Australia". The Queensland Times. 21 August 2018. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ a b Campbell, Jon (15 February 2017). "Gavin McInnes Wants You to Know He's Totally Not a White Supremacist". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Swenson, Kyle (10 July 2017). "The alt-right's Proud Boys love Fred Perry polo shirts. The feeling is not mutual". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Cross, Katharine (15 February 2017). "We need to talk about Chelsea Manning". The Verge. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "New 'Fight Club' Ready for Street Violence". Southern Poverty Law Center. 25 April 2017. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Armstrong, Liz (16 September 2004). "Shithead". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ "The Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers: 2 controversial groups involved in major protests". ABC News. 19 July 2018. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin; Winston, Ali (23 December 2018). "Far-Right Proud Boys Reeling After Arrests and Scrutiny". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Ex-Vice founder: Israelis have 'whiny paranoid fear of Nazis'". Times of Israel. 16 March 2017. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Marcotte, Amanda (16 March 2017). "Bad boy gone worse: Vice co-founder Gavin McInnes slides from right-wing provocateur to the neo-Nazi fringe". Salon. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Csillag, Ron (17 March 2017). "Rebel's Gavin McInnes gets flak from CIJA for offensive videos about Jews and Israel". Canadian Jewish News. Archived from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ a b Sparks, Riley (15 March 2017). "Rebel Media is defending contributor behind 'repulsive rant' that was praised by white supremacists". Canada's National Observer. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d Rosenberg, David (21 March 2017). "'10 things I hate about Jews' satirical video stirs controversy". Israel National News. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (12 March 2017). "What Gavin McInnes really thinks about the Holocaust". Rebel News, YouTube. Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (5 December 2022). "The Ye Interview". New York. New York, United States. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022 – via Censored.TV.

- ^ "Controversial Proud Boys Embrace 'Western Values,' Reject Feminism And Political Correctness". Wisconsin Public Radio. 26 November 2017. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ "Inside Rebel Media". National Post. 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Gavin McInnes: 'Nazis Are Not A Thing. Islam Is A Thing'". Right Wing Watch. 18 August 2017. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ "37 Organizations and a Regional Organization Representing Over 50 Tribes Denounce Bigotry and Violence before Patriot Prayer and Proud Boys Rally in Portland on August 4". The Skanner. 3 August 2018. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ "Gavin McInnes: Feminism kills women". Rebel Media. 8 May 2017. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021.

- ^ Sutton, Scott (15 May 2015). "Gavin McInnes might be the most sexist man on the planet". National. Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- ^ Bonk, Lawrence (20 May 2015). "Gavin McInnes Explains 'Sexist' Comments That Ruffled Feathers...By Totally Doubling Down on Them". Independent Journal Review. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ Marcotte, Amanda (16 March 2017). "Bad boy gone worse: Is Vice co-founder Gavin McInnes flirting with a dangerous fringe?". Salon. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ Davies, Madeleine (22 October 2013). "Vice Co-Founder Throws Epic Tantrum About Women Defying Gender Roles". Jezebel. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Vice Co-Founder Gavin McInnes on Trolling Feminists: I'm Not Andy Kaufman; This Isn't a Joke". The Hollywood Reporter. 18 May 2015. Archived from the original on 20 November 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Marcotte, Amanda (31 October 2013). "Most Women Work Because They Have To". Slate. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Gavin McInnes: 'Feminism has Made Women Less Happy'". ABC News. 22 October 2013. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ Buxton, Ryan (21 October 2013). "Gavin McInnes Launches Expletive-Laden Tirade About Women In The Workplace (VIDEO)". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 27 October 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ Ciara LaVelle (24 October 2013). "UM Law Professor Mary Anne Franks Issues Epic Feminist Beatdown on Vice Founder Gavin McInnes". Miami New Times. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ "Neo-Nazis, white nationalists, and internet trolls: who's who in the far right". The Guardian. 17 August 2017. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ *"Do You Want Bigots, Gavin? Because This Is How You Get Bigots". Southern Poverty Law Center. 10 August 2017. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "How Hate Goes 'Mainstream': Gavin McInnes and the Proud Boys". Rewire.News. 28 August 2017. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- "Proud Boy lawyer demands alt-weeklies not call "western chauvinist fraternity" alt-right". Baltimore City Paper. 25 October 2017. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ""Proud Boys" Founder Wants to "Trigger the Entire State of Oregon" by Helping Patriot Prayer's Joey Gibson win the Oregon Person of the Year Poll". The Portland Mercury. 12 December 2017. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ "With Trump's South Africa tweet, Tucker Carlson has turned a white nationalist narrative into White House policy". Media Matters. 23 August 2018. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Jean Latz Griffin (September 1993), "NATIVE AMERICANS FIGHT CULTURE THIEVES", CHICAGO TRIBUNE

- ^ Marcotte, Amanda (17 October 2018). "Gavin McInnes and the Proud Boys: "Alt-right without the racism"?". Salon. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Fitz-Gibbon, Jorge; Rom, Gabriel (19 November 2018). "Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes and Trump critic Amy Siskind come face-to-face". The Journal News. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Bałaga, Marta (18 November 2020). "'White Noise' Director on Alt-Right: 'As Long as Trump Refuses to Concede, This Stuff Is Just Going to Fester'". Variety. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ Lombroso, Daniel (16 October 2020). "Why the Alt-Right's Most Famous Woman Disappeared". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Gollner, Adam Leith (July–August 2021). "Original sins". Vanity Fair. Vol. 730. pp. 82–89, 131–133.

KSF

KSF