George Butterworth

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

George Butterworth | |

|---|---|

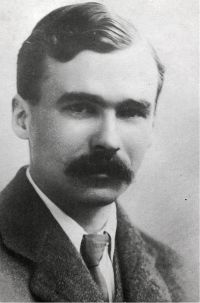

George Butterworth, c. 1914 | |

| Born | George Sainton Kaye Butterworth 12 July 1885 Paddington, London, England |

| Died | 5 August 1916 (aged 31) |

| Cause of death | Killed in action |

| Resting place | Unknown |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Oxford |

| Occupation(s) | Composer, schoolmaster, music critic, professional morris dancer, soldier |

| Parent(s) | Sir Alexander Kaye Butterworth; Julia Marguerite Wigan |

| Relatives | Joseph Butterworth (great great grandfather) Hugh Butterworth (cousin) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1914–1916 |

| Rank | Subaltern |

| Unit | 13th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry |

| Battles / wars | First World War |

George Sainton Kaye Butterworth, MC (12 July 1885 – 5 August 1916) was an English composer who was best known for the orchestral idyll The Banks of Green Willow and his song settings of A. E. Housman's poems from A Shropshire Lad. He was awarded the Military Cross for his gallantry during the fighting at Pozières in the First World War, and died in the Battle of the Somme.

Early years

[edit]

Butterworth was born in Paddington, London.[1] Soon after his birth, his family moved to York so that his father Sir Alexander Kaye Butterworth could take up an appointment as general manager of the North Eastern Railway, which was based there.[2] Their home was at Riseholme, a house on Driffield Terrace, which later became part of the Mount School. In 2016, the centenary year of his death on the Somme, biographer Anthony Murphy unveiled on behalf of the York Civic Trust a blue plaque to his memory at College House, Driffield Terrace, part of the Mount School.

George received his first music lessons from his mother, who was a singer, and he began composing at an early age.[2] As a young boy, he played the organ for services in the chapel of his preparatory school, Aysgarth School, before gaining a scholarship to Eton College.[2] He showed early musical promise at Eton, a "Barcarolle" for orchestra being played during his time there (it is long since lost).[3]

Butterworth then went up to Trinity College, Oxford, where he became more focused on music, becoming President of the University Music Club.[2] He also made friends with the folk song collector Cecil Sharp; the composer and folk song enthusiast Ralph Vaughan Williams; the future Director of the Royal College of Music, Hugh Allen; and a baritone and future conductor, Adrian Boult. Butterworth and Vaughan Williams made several trips into the English countryside to collect folk songs (Butterworth collected over 450 himself, many in Sussex in 1907, and sometimes using a phonograph) and the compositions of both were strongly influenced by what they collected.[2] Butterworth was also an expert folk dancer, being particularly keen in the art of morris dancing.[2] He was employed for a while by the English Folk Dance and Song Society (of which he was a founder member in 1906) as a professional morris dancer, and was a member of the Demonstration Team.[4]

Upon leaving Oxford, Butterworth began a career in music, writing criticism for The Times, composing, and teaching at Radley College, Oxfordshire.[2] He also briefly studied piano and organ at the Royal College of Music, where he worked with Hubert Parry among others, though he stayed less than a year as the academic life was not for him.[2]

Vaughan Williams and Butterworth became close friends. It was Butterworth who suggested to Vaughan Williams that he turn a symphonic poem he was working on into his London Symphony. Vaughan Williams recalled:

We were talking together one day when he said in his gruff, abrupt manner: ‘You know, you ought to write a symphony’. I answered...that I’d never written a symphony and never intended to...I suppose Butterworth’s words stung me and, anyhow, I looked out some sketches I had made for...a symphonic poem about London and decided to throw it into symphonic form...From that moment, the idea of a symphony dominated my mind. I showed the sketches to George bit by bit as they were finished, and it was then that I realised that he possessed in common with very few composers a wonderful power of criticism of other men’s work and insight into their ideas and motives. I can never feel too grateful to him for all he did for me over this work and his help did not stop short at criticism.[5]

When the manuscript for that piece was lost (having been sent to Germany, either to the conductor Fritz Busch or for engraving, just before the outbreak of war), Butterworth, together with Geoffrey Toye and the critic Edward J. Dent, helped Vaughan Williams reconstruct the work.[6] Vaughan Williams dedicated the piece to Butterworth's memory after his death.

First World War

[edit]

One of "the lads that will die in their glory and never be old"

At the outbreak of the First World War, Butterworth, together with several of his friends, including Geoffrey Toye and R. O. Morris, joined the British Army as a private in the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry, but he soon accepted a commission as a subaltern (2nd Lieutenant) in the 13th Battalion Durham Light Infantry, and he was later temporarily promoted to lieutenant.[2] He was known as G. S. Kaye-Butterworth in the Army.[2] Butterworth's letters are full of admiration for the ordinary miners of County Durham who served in his platoon. As part of 23rd Division, the 13th DLI was sent into action to capture the western approaches of the village of Contalmaison on The Somme. Butterworth and his men succeeded in capturing a series of trenches near Pozières on 16–17 July 1916, the traces of which can still be found within a small wood. Butterworth was slightly wounded in the action. For his action Temporary Lt. George Butterworth, aged 31, was awarded the Military Cross, gazetted 25 August 1916, though he did not live to receive it. The citation for the medal reads as follows:

For conspicuous gallantry in action. After his captain had been wounded, Butterworth commanded his company with great ability and coolness, and with his energy and utter disregard of danger he set a fine example on the front line. His name had previously been brought to notice for good and gallant work.[7]

The Battle of the Somme was now entering its most intense phase. On 4 August, 23rd Division was ordered to attack a communications trench known as Munster Alley that was in German hands. The soldiers dug an assault trench and named it 'Butterworth Trench' in their officer's honour. In desperate fighting during the night of 4–5 August, and despite friendly fire from Australian artillery, Butterworth and his miners captured and held on to Munster Alley, albeit with heavy losses. At 04:45 on 5 August, amid frantic German attempts to recapture the position, Butterworth was shot through the head by a sniper. His body was hastily buried by his men in the side of the trench, but was never recovered for formal reburial following the fierce bombardments of the final two years of conflict.

When his brigade commander, Brigadier General Page Croft, wrote to Butterworth's father to inform him of his death, it transpired that he had not known that his son had been awarded the Military Cross.[2] Similarly, the brigadier was astonished to learn that Butterworth had been one of the most promising English composers of his generation.[2] Brigadier Croft wrote that Butterworth was "A brilliant musician in times of peace, and an equally brilliant soldier in times of stress."[8]

There is confusion about exactly what award(s) Butterworth received. It is said that he won the MC twice, but this is incorrect. This misunderstanding may have arisen because Butterworth's bravery was regularly in evidence during the Somme campaign. Firstly, he was mentioned in despatches early in July, and was then recommended for the MC "for conspicuous gallantry in action" on 9 July at Bailiff Wood, then again – successfully – "for commanding his company with great ability and coolness" when wounded on 16–17 July. Brigadier Page-Croft also mentioned to Butterworth's father that he had 'won' the medal again on the night he died. However, the Military Cross was not awarded posthumously at the time, and so he could never have been awarded it twice.[9]

Butterworth's body was never recovered (although his unidentified remains may well lie at nearby Pozières Memorial, a Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery), and his name appears on the Thiepval Memorial.[2] George Butterworth's The Banks of Green Willow has become synonymous for some with the sacrifice of his generation and has been seen by some as an anthem for all 'Unknown Soldiers'. Sir Alexander Butterworth erected a plaque at St Mary's Priory Church, Deerhurst, Gloucestershire in memory of his son and of his nephew, Hugh, who died at Loos in 1915. (The Rev. George Butterworth, the composer's grandfather, had been vicar of St Mary's in the previous century.[2]) Sir Alexander also arranged the printing in 1918 of a memorial volume in his son's memory. His name is one of the 38 on the War Memorial at the Royal College of Music.

Almost all Butterworth's manuscripts were left to Vaughan Williams, after whose death Ursula Vaughan Williams lodged the original works in the Bodleian, Oxford, and the folk song collection with the EFDSS.[2]

A Shropshire Lad, and other compositions

[edit]Butterworth did not write a great deal of music, and before and during the war he destroyed many works he did not care for, lest he should not return and have the chance to revise them.[2] Of those that survive, his works based on A. E. Housman's collection of poems A Shropshire Lad are among the best known. Many English composers of Butterworth's time set Housman's poetry, including Ralph Vaughan Williams.

In 1911 and 1912, Butterworth wrote eleven settings of Housman's poems from A Shropshire Lad. The poems are

- "Loveliest of Trees"

- "When I Was One and Twenty"

- "Look Not in My Eyes"

- "Think No More, Lad"

- "The Lads in Their Hundreds"

- "Is My Team Ploughing?"

- "Bredon Hill"

- "Oh Fair Enough Are Sky and Plain"

- "When the Lad for Longing Sighs"

- "On the Idle Hill of Summer"

- "With Rue My Heart Is Laden"

He used no known folk tunes in the songs, although one ("When I Was One and Twenty") was said to be based on a folk tune that has defied identification.[2] The songs were dedicated to Victor Annesley Barrington-Kennett, a friend from Eton and Oxford, who was also to die in France in 1916.[2] They were eventually published in two sets, Six Songs from A Shropshire Lad (1–6 above) and Bredon Hill and Other Songs (7–11), although the composer never settled on a preferred order.[3] Nine of the songs were first performed by James Campbell McInnes (baritone) and Butterworth (piano) on 16 May 1911 at a meeting of the Oxford University Musical Club, organized by Boult.[2] Shortly thereafter Boult sang several of the songs at a private function. At this stage, Butterworth still had not completed "On the idle hill of summer" and did not do so until he was living at Cheyne Gardens in London. It is unusual for the songs to be given publicly in full, although each of the published sets is often performed separately and recorded regularly – in fact, they can be said to be among the most frequently performed English art songs.[10] Six Songs from A Shropshire Lad is the more popular set, with "Is My Team Ploughing?" being the most famous song. Another, "Loveliest of Trees", is the basis for his 1912 orchestral rhapsody, also called A Shropshire Lad, which quotes two songs from the whole – "Loveliest of Trees" and "With Rue My Heart Is Laden".

The parallel is regularly made[2][11] between the often gloomy and death-obsessed subject matter of A Shropshire Lad, written in the shadow of the Second Boer War, and Butterworth's subsequent death during the Great War. In particular, the song "The lads in their hundreds" tells of young men who leave their homeland to 'die in their glory and never be old'.

The Rhapsody, A Shropshire Lad – a sort of postlude to the songs – employs a normal sized symphony orchestra, and was first performed on 2 October 1913 at the Leeds Festival, conducted by Arthur Nikisch.[2] It was influential upon Vaughan Williams (A Pastoral Symphony), Gerald Finzi (A Severn Rhapsody) and Ernest Moeran (First Rhapsody).[3] Butterworth's other orchestral works are short and based on folksongs he had collected in Sussex in 1907: Two English Idylls (1911) and The Banks of Green Willow (1913). They are often performed and recorded, Banks particularly so. The latter work was premiered by the 24-year-old Adrian Boult on 27 February 1914, at West Kirby, Wirral, (this was in fact Boult's very first professional concert).

Love Blows As the Wind Blows is a setting of poems by W. E. Henley. It exists in three forms: for voice and string quartet, voice and piano and voice and small orchestra.[2] The orchestral version differs from the others quite markedly, not least in having only three songs: "In the Year That's Come and Gone", "Life in Her Creaking Shoes", and "On the Way to Kew" (the other versions include "Fill a Glass with Golden Wine"). The orchestral version was in fact the last music Butterworth worked on before leaving for France, and shows the composer's familiarity with Vaughan Williams' style, as well as with the music of Wagner, Elgar and Debussy.[3]

Butterworth showed real talent that might have flourished but for his early death.[11] The Two English Idylls and The Banks of Green Willow show an ability to handle folk song in a way that eluded many other composers – as the true building blocks of larger forms.[2] His original music (especially the Rhapsody: A Shropshire Lad and the orchestral song cycle Love Blows As The Wind Blows) have a delicacy that brings to mind Debussy or Ibert.[2] However, there is reasonable evidence that he had put composition behind him by the time he went to France, and it is by no means certain that he would have resumed it had he returned.[2] It is certainly likely that he would have faced considerable pressure from friends to compose again, since his orchestral works (particularly the Rhapsody: A Shropshire Lad) had made a great impression, but he was a single-minded man who was unlikely to bow easily to such pressure.[12] He remains perhaps the most obvious case of "what if...?" that is left to us from the battlefields of northern France, and he joins the Frenchman Albéric Magnard, the Spaniard Enrique Granados, and the German Rudi Stephan as possibly the greatest losses to music[11] from the First World War. The great conductor Carlos Kleiber saw in Butterworth a special gift. In his 1978 appearance with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra he programmed, to the surprise of many, Butterworth's English Idyll No. 1.

List of compositions

[edit]This article uses shallow references to the home page or some other high level page of a website that contains the cited document. (August 2016) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

Butterworth's complete extant works are:[13]

- Two English Idylls for orchestra (1910–1911)

- A Shropshire Lad, Rhapsody for orchestra (1911)

- The Banks of Green Willow for orchestra (1913)

- Love Blows As the Wind Blows, a song cycle for voice and piano (or string quartet) (both 1911–12) or small orchestra (1914) [words William Ernest Henley]

- Suite for String Quartet (1910)[14]

- Eleven Songs from A Shropshire Lad (i.e., Six Songs from A Shropshire Lad, and Bredon Hill and Other Songs) (1910–1911) [words A. E. Housman]

- Folk Songs From Sussex (1912)

- Haste On, My Joys!, song (date unknown, probably pre-1906) [words Robert Bridges]

- I Will Make You Brooches (date unknown) [words Robert Louis Stevenson]

- I Fear Thy Kisses (1909) [words Percy Bysshe Shelley]

- Requiescat, song (1911) [words Oscar Wilde]

- In The Highlands, for female voices and piano (poss. 1912) [words R. L. Stevenson]

- On Christmas Night, for male chorus (poss. 1912) [folksong]

- We Get Up In The Morn, for male chorus (poss. 1912) [folksong]

- Morris Dance Tunes Books 8 & 9 (1914)[15]

Arrangements of Butterworth's compositions

[edit]- Fantasia for Orchestra (1914), edited and completed by Martin Yates[16]

- Fantasia for Orchestra (1914), edited and completed by Kriss Russman[17]

- Two English Idylls (arranged for piano duet by John Mitchell) (1999)[18]

- A Shropshire Lad: Rhapsody (arranged for piano by John Mitchell) (2011)[19]

- Suite for Small Orchestra (arrangement of the Suite for String Quartet by Phillip Brookes) (2012)[20]

- Suite for String Quartette (arranged for String Orchestra by Kriss Russman) (2015)

- Eleven Songs from A Shropshire Lad (with accompaniment for small orchestra, arranged by Phillip Brookes) (2006)[21]

- Six Songs from A Shropshire Lad (with accompaniment for orchestra by Kriss Russman) (2015)

Other writings

[edit]The Country Dance Book, parts 3 (1912)[22] and 4 (1916)[23] with Cecil Sharp

Recordings

[edit]- All three orchestral works (Two English Idylls, A Shropshire Lad: Rhapsody. and The Banks of Green Willow)

- Boult/LPO (rec. 1973); Lyrita SRCD 245

- Marriner/ASMF (rec. 1976); Decca 468 802-2

- Boughton/English String Orchestra (rec. 1986); Nimbus NI 5068

- Llewellyn/RLPO (rec. 1991); Decca 436 401-2

- Elder/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 2002); Hallé CD HLL 7503

- Russman/BBC National Orchestra of Wales (rec. 2015); BIS Records BIS-2195

- Two English Idylls only

- Boult/British Symphony Orch. (No. 1 only, rec. 1922); HMV Cc1129

- Dilkes/English Sinfonia (rec. 1971); HMV ESD 7101

- Carlos Kleiber/Chicago SO (No. 1 only, rec. 2 June 1983); Memories CD

- Tate/English Chamber Orchestra (rec. 1987); EMI CDC7 47945-2

- Horvay/Prague Radio SO (No. 2 only, date unknown); Artist’s Rifles CD41

- Wilson/Royal Liverpool PO (rec. 2011) Avie

- A Shropshire Lad: Rhapsody only

- Boult/British Symphony Orch. (rec. 1920); HMV 4618AF

- Boult/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942); VAI Audio VAIA 1067-2

- Stokowski/NBC SO (rec. 1944); Cala CACD 0528

- Goossens/Sydney SO (rec 1952); HMV DB 9792-3

- Boult/LPO (rec. 1954); Belart CD 461354-2

- Barbirolli/ Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1956); Barbirolli Society SJB 1022

- Barbirolli/ Hallé Orchestra; EMI 4577672

- Dilkes/English Sinfonia (rec. 1971); HMV CSD 3696

- Elder/Halle Orchestra (rec. 2002); BBC MM 289

- The Banks of Green Willow

- See the separate page

Fantasia for Orchestra (completed by Kriss Russman)

- Russman/BBC National Orchestra of Wales (rec.2015) BIS Records BIS 2195

- Songs (complete)

- The Complete Butterworth Songbook: Stone/Barlow; Stone Records 5060192780024 (All Butterworth’s songs, including the voice/piano version of Love Blows. It also includes a short silent film of Butterworth morris dancing. The tracks from this disc are included among the details below.)

- All eleven Shropshire Lad songs ('Six Songs' and 'Bredon Hill and Other Songs')

- Cameron/Moore; Dutton

- Luxon/Willison (rec. 1976); Decca 468 802-2

- Luxon/Willison (rec. 1990); Chandos CHAN 8831

- Williams/Burnside; Naxos 8.572426

- Rolfe-Johnson/Johnson; Hyperion CDD22044

- Terfel/Martineau(rec. 1995); DG 445946

- Allen/Parsons (rec. 2001) EMI 67428

- Maltman/Vignoles; Hyperion CDA 67378

- Stone/Barlow; Stone Records 5060192780024

- Keenlyside/Martineau; Sony Classical 88697 94424-2

- Rutherford/Asti (rec. 2012); BIS SACD 1610

- Six Songs from A Shropshire Lad only

- Henderson/Moore (rec. 1941); Dutton CDLX 7038

- Shirley-Quirk/Isepp (rec. 1966); Saga STXID5260

- Rayner Cook/Benson; Unicorn

- Gehrman/Farmer; Nimbus NI 5033

- Rolfe-Johnson/Willinson; EMI

- Lemalu/Burnside (rec. 2003); BBC MM298

- Allen/Martineau; Wigmore Hall Live WHLIVE0002

- Polegato/Burnside CBC Records

- Trew/Vignoles; Meridian CDE84185

- Varcoe/Hickox/City of London Sinfonia (orch. Lance Baker) (rec. 1989); Chandos CHAN 8743

- I will Make You Brooches

- Williams/Burnside; Naxos 8.572426

- Stone/Barlow; Stone Records 5060192780024

- I Fear Thy Kisses

- Williams/Burnside; Naxos 8.572426

- Stone/Barlow; Stone Records 5060192780024

- Requiescat

- Varcoe/Benson; Hyperion CDA 6621/2

- Williams/Burnside; Naxos 8.572426

- Stone/Barlow; Stone Records 5060192780024

- Love Blows as the Wind Blows

- (Voice and piano)

- Stone/Barlow; Stone Records 5060192780024

- (Voice and string quartet)

- Oxenham/Bingham String Quartet; Meridian DUOCD 89026

- Lemalu/Belcea Quartet (rec. 2005); EMI 5 58050

- (Voice and orchestra)

- Rutherford/Russman/BBC NOW (rec.2015) BIS Records BIS 2195

- Tear/Handley/CBSO; EMI CDM7 64731-2

- Varcoe/Hickox/City of London Sinfonia (rec. 1989); Chandos CHAN 8743

- Folk Songs from Sussex

- Williams/Burnside; Naxos 8.572426

- Stone/Barlow; Stone Records 5060192780024

- Folk songs collected by Butterworth

- Triple Echo by Coope, Boyes and Simpson contains songs from the Butterworth collection. The Banks of Green Willow, The Cuckoo and The Turtle Dove are given with all verses. There are also songs collected by Vaughan Williams and Grainger. (Rec 2005); No Masters NMCD22

Roads

[edit]Three roads are named after Butterworth:

- Butterworth Road, Trichirappali, Tamil Nadu, India (10°49′50″N 78°41′52″E / 10.830471°N 78.69789°E).

- Butterworth Close in Newport, south Wales (51°35′27″N 2°56′05″W / 51.59082°N 2.934842°W), one of several named after composers.[24]

- Chemin George Butterworth[25] (George Butterworth Lane; 50°02′28″N 2°43′59″E / 50.041172°N 2.733112°E), at Pozières on the Somme battlefield.[26]

Bibliography

[edit]- George Butterworth Memorial Volume, privately printed, 1918

- Copley, Ian (1985). George Butterworth and his Music : a centennial tribute. London: Thames Publishing. ISBN 9780905210292.

- Barlow, Michael (1997). Whom the Gods Love : the Life and Music of George Butterworth (1. publ. ed.). London: Toccata Press. ISBN 9780907689423.

- Barlow, Michael and Brookes, Phillip: Prefaces to 3 volumes of the works of George Butterworth, Musikproduktion Jürgen Höflich, Munich, 2006 and 2007

- Murphy, Anthony: Banks of Green Willow: The Life and Times of George Butterworth, Cappella Archive, Malvern, 2012. 2nd revised and updated edition, 2015. ISBN 9781902918624

See also

[edit]- Charles James Mott – "Elgar's Baritone" (died of wounds in 1918)

- Ivor Gurney

References

[edit]- ^ England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes, General Register Office, volume 1a, p. 27

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Barlow 1997.

- ^ a b c d Barlow, Michael, preface to three volumes of Butterworth's music, Musikproduktion Jürgen Höflich, Munich 2006 & 2007

- ^ Barlow 1997, in which there are photographs of Butterworth dancing.

- ^ Lloyd, Stephen, in Ralph Vaughan Williams in Perspective, ed. Lewis Foreman, Albion Music Ltd, 1998; the quoted text is a portmanteau of two originals, the bulk being from a letter to Sir Alexander Butterworth, father of the composer

- ^ Mann, William, liner notes to EMI CD CDM 7 64017 2, 1987

- ^ "No. 29724". The London Gazette (Supplement). 25 August 1916. p. 8461.

- ^ Page Croft, H. (1917). Twenty Two Months Under Fire. London: John Murray. p. 237.

- ^ Copley 1985, contains much information on Butterworth's war record, including sources for all military quotes..

- ^ Hall, George, booklet notes to Deutsche Grammophon CD 445946-2

- ^ a b c Stone, Mark, booklet notes to Stone Records CD 5060192780024

- ^ Banfield, Stephen, Sensibility and English Song, 1985, Cambridge University Press, p. 153

- ^ "Musikproduktion Hoeflich Muenchen | Phenomenology of Music". Musikmph.de. 31 December 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Butterworth, George (2001) [1910]. Suite for String Quartet. Enfield: Modus Music.

- ^ Butterworth, George; Sharp, Cecil (1914). Morris Dance Tunes. Vol. 8, 9. London: Novello & Co.

- ^ "Fantasia for Orchestra". BBC. 10 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ "Fantasia for Orchestra". BBC. 10 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ Mitchell, John (1999). Two English Idylls (piano duet arrangement). Enfield: Modus Music.

- ^ Mitchell, John (2011). A Shropshire Lad: Rhapsody (piano arrangement). Enfield: Modus Music.

- ^ Brookes, Phillip (2012). Suite for Small Orchestra. Munich: Musikproduktion Juergen Hoeflich.

- ^ Brookes, Phillip (2006). Eleven Songs from A Shropshire Lad (with accompaniment for small orchestra). Munich: Musikproduktion Juergen Hoeflich.

- ^ Butterworth, George; Sharp, Cecil (1912). The Country Dance Book. Vol. 3. London: Novello & Co.

- ^ Butterworth, George; Sharp, Cecil (1916). The Country Dance Book. Vol. 4. London: Novello & Co.

- ^ South Wales Argus, 27 May 2009.

- ^ "Butterworth Farm". Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ "Le chemin George Sainton Kaye Butterworth Lane". Images-en-somme.fr. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

External links

[edit]- Free scores by George Butterworth at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Artists Rifles WW1 audio CD featuring Butterworth

- York Civic Trust Blue Plaque

- Sheet music edition of Suite for String Quartet published by Artaria Editions

- All MY Life's Buried Here: The Story of George Butterworth, Film directed by Stewart Hajdukiewicz (2018)

KSF

KSF